Difference between revisions of "Crow Nation" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

The [[Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851]] confirmed a large area centered on the Big Horn Mountains as Crow lands—the area ran from the [[Big Horn Basin]] on the west, to the [[Musselshell River]] on the north, and east to the [[Powder River (Montana)|Powder River]], and included the Tongue River [[Drainage basin|basin]].<ref>Charles J. Kappler (ed.), [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/sio0594.htm#mn10 Article 5] Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011.</ref> However, for two centuries, the [[Cheyenne]] and many bands of [[Lakota]] had been steadily migrating westward across the plains, and by 1851 they were established just to the south and east of Crow territory in Montana.<ref name="brown">Mark H. Brown, ''The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone: A History of the Yellowstone Basin'' (Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0803250260), 128–129.</ref> These tribes coveted the fine hunting lands of the Crow and conducted tribal warfare against them, pushing the less numerous Crow to the west and northwest along the [[Yellowstone River|Yellowstone]], although the Crow defended themselves, often successfully. | The [[Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851]] confirmed a large area centered on the Big Horn Mountains as Crow lands—the area ran from the [[Big Horn Basin]] on the west, to the [[Musselshell River]] on the north, and east to the [[Powder River (Montana)|Powder River]], and included the Tongue River [[Drainage basin|basin]].<ref>Charles J. Kappler (ed.), [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/sio0594.htm#mn10 Article 5] Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011.</ref> However, for two centuries, the [[Cheyenne]] and many bands of [[Lakota]] had been steadily migrating westward across the plains, and by 1851 they were established just to the south and east of Crow territory in Montana.<ref name="brown">Mark H. Brown, ''The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone: A History of the Yellowstone Basin'' (Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0803250260), 128–129.</ref> These tribes coveted the fine hunting lands of the Crow and conducted tribal warfare against them, pushing the less numerous Crow to the west and northwest along the [[Yellowstone River|Yellowstone]], although the Crow defended themselves, often successfully. | ||

| − | During the period of the [[Indian Wars]], the Crow supported the United States military by supplying [[scout]]s and protecting travelers on the [[Bozeman Trail]]. Chief [[Plenty Coups]] encouraged this, believing that the Americans would win the war and would remember their Crow allies, ensuring their survival in the white man's world.<ref name=Waldman> Carl Waldman, ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744), 88.</ref> | + | During the period of the [[Indian Wars]], the Crow supported the United States military by supplying [[scout]]s and protecting travelers on the [[Bozeman Trail]]. Chief [[Plenty Coups]] encouraged this, believing that the Americans would win the war and would remember their Crow allies, ensuring their survival in the white man's world.<ref name=Waldman> Carl Waldman, ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744), 86-88.</ref> |

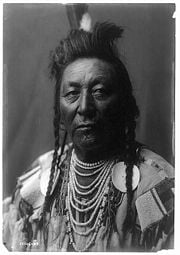

[[Image:Plenty Coups Edward Curtis Portrait (c1908).jpg|thumb|right|180px| Portrait of Plenty Coups (c.1908).]] | [[Image:Plenty Coups Edward Curtis Portrait (c1908).jpg|thumb|right|180px| Portrait of Plenty Coups (c.1908).]] | ||

[[Red Cloud's War]] (1866 to 1868) was a challenge by the Lakota Sioux to the military presence on the [[Bozeman Trail]], which went to the [[Montana]] [[gold]] fields along the eastern edge of the [[Big Horn Mountains]]. Red Cloud's War ended in a victory for the Lakota Sioux, and the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie confirmed their control over all the high plains from the crest of the Big Horn Mountains eastward across the [[Powder River Basin]] to the [[Black Hills]].<ref>Charles J. Kappler (ed.), [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/sio0998.htm#mn5 Treaty with the Sioux-Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee-and Arapaho, 1868] (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011. See Article 16, creating unceded Indian Territory east of the summit of the Big Horn Mountains and north of the North Platte River.</ref> Thereafter bands of Lakota Sioux led by [[Sitting Bull]], [[Crazy Horse]] and others, along with their [[Northern Cheyenne]] allies, hunted and raided throughout the length and breadth of [[eastern Montana]] and northeastern [[Wyoming]] - ancestral Crow territory. Although early in the war on June 25, 1876 the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne enjoyed a major victory over army forces under General [[George A. Custer]] at the [[Battle of the Little Big Horn]], the [[Great Sioux War]] (1876 - 1877) ended in the defeat of the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies, and their exodus from eastern Montana and Wyoming, either in flight to [[Canada]] or by forced removal to distant [[Indian reservation|reservation]]s. | [[Red Cloud's War]] (1866 to 1868) was a challenge by the Lakota Sioux to the military presence on the [[Bozeman Trail]], which went to the [[Montana]] [[gold]] fields along the eastern edge of the [[Big Horn Mountains]]. Red Cloud's War ended in a victory for the Lakota Sioux, and the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie confirmed their control over all the high plains from the crest of the Big Horn Mountains eastward across the [[Powder River Basin]] to the [[Black Hills]].<ref>Charles J. Kappler (ed.), [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/sio0998.htm#mn5 Treaty with the Sioux-Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee-and Arapaho, 1868] (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011. See Article 16, creating unceded Indian Territory east of the summit of the Big Horn Mountains and north of the North Platte River.</ref> Thereafter bands of Lakota Sioux led by [[Sitting Bull]], [[Crazy Horse]] and others, along with their [[Northern Cheyenne]] allies, hunted and raided throughout the length and breadth of [[eastern Montana]] and northeastern [[Wyoming]] - ancestral Crow territory. Although early in the war on June 25, 1876 the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne enjoyed a major victory over army forces under General [[George A. Custer]] at the [[Battle of the Little Big Horn]], the [[Great Sioux War]] (1876 - 1877) ended in the defeat of the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies, and their exodus from eastern Montana and Wyoming, either in flight to [[Canada]] or by forced removal to distant [[Indian reservation|reservation]]s. | ||

Revision as of 21:02, 2 December 2011

| Crow Nation |

|---|

| Total population |

| 11,000-12,000 enrolled members |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Billings, Hardin, Bozeman, Missoula, Albuquerque, Denver, Lawrence, Bismarck, Spokane, Seattle, Chicago |

| Languages |

| Crow, English |

| Religions |

| Crow Way, Sundance, Tobacco Society, Christian: Catholic, Pentecostal, Baptist |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Hidatsa |

The Crow, also called the Absaroka or Apsáalooke, are a tribe of Native Americans who historically lived in the Yellowstone river valley and now live on a reservation south of Billings, Montana, USA. The tribal headquarters are located at Crow Agency, Montana.

Name

The name of the tribe, Apsáalooke (or Absaroke), had been mistranslated by early French interpreters as gens des corbeaux "people of [the] crows." It actually meant "people [or children] of the large-beaked bird."[1][2] The bird, perhaps now extinct, was defined as a fork-tailed bird resembling the blue jay or magpie.

Language

Crow is a Missouri Valley Siouan language spoken primarily by the Crow Nation in present-day Montana. It is closely related to Hidatsa spoken by the Hidatsa tribe of the Dakotas; the two languages are the only members of the Missouri Valley Siouan family.[3][4] Crow and Hidatsa are not mutually intelligible, however the two languages share many phonological features, cognates, and have similar morphologies and syntax.

The Crow language has one of the larger populations of American Indian languages with 4,280 speakers according to the 1990 US Census.[5] Daily contact with non-American Indians on the reservation for over one hundred years has led to high usage of English with the result that Crow speakers are usually bilingual in English. Traditional culture within the community, however, has preserved the language via religious ceremonies and the traditional clan system.

History

Some historians believe the early home of the Crow-Hidatsa ancestral tribe was near the headwaters of the Mississippi River in either northern Minnesota or Wisconsin; others place them in the Winnipeg area of Manitoba. Later the people moved to the Devil's Lake region of North Dakota where they settled for many years before they separated into the Crow and the Hidatsa.

Pre-contact

In the fifteenth century or earlier, the Crow were pushed westward by the influx of Sioux who were pushed west by European-American expansion. The Crow separated from the Hidatsa in two main groups: the Mountain Crow and the River Crow.

The Mountain Crow, or Ashalaho, the largest Crow group, were the first to separate when their leader, No Intestines, received a vision and led his band on a long migratory search for sacred tobacco, finally settling in southeastern Montana.[6] They established themselves in the Valley of the Yellowstone River and its tributaries on the Northern Plains in Montana and Wyoming.[2][7] They lived in the Rocky Mountains and foothills on the Wyoming-Montana border along the Upper Yellowstone River, in the Big Horn and Absaroka Range (also Absalaga Mountains) with the Black Hills on the eastern edge of their territory. The Hidatsa remained settled around the Missouri River where they joined with the Mandan and lived an agricultural lifestyle.

The River Crow, or Binnéassiippeele, split from the Hidatsa (according to oral tradition) over a dispute over a bison stomach.[6] They lived along the Yellowstone River and Musselshell River south of the Missouri River, and in the river valleys of the Big Horn, Powder River, and Wind River, (historically known as the Powder River Country), sometimes traveling north up to the Milk River.[8][2]

Formerly semi-nomadic hunters and farmers in the northeastern woodland, the Crow picked up the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Plains Indians, hunting bison and using dog travois for carrying goods.[9] After the spread of the horse in the Great Plains in mid-eighteenth century, various eastern and northern tribes pushed on the Plains, in search of game, bison, and more horses. Because the Crow, Hidatsa, and Shoshone were particularly famous as horse breeders and dealers and therefore had large horse herds, they became soon the target of many horse thefts by neighboring tribes.[10] This brought the Crow into conflict with the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy, Gros Ventre, Assiniboine, Pawnee, Ute, and later the Lakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne, who stole the horses rather than acquiring them through trade.

To acquire control of their areas, they warred against Shoshone bands,[11] and drove them westward, but allied themselves with local Kiowa and Kiowa Apache bands.[12][13] The Kiowa and Kiowa Apache bands then migrated southward, but the Crow remained dominant in their established area through the eighteenth century and nineteenth centuries.

Post-contact

The Crow first encountered Europeans in 1743 when they met the La Verendrye brothers, French-Canadian traders, near the present-day town of Hardin, Montana. These explorers called the Apsáalooke beaux hommes, "handsome men." The Crow called white people baashchiile, "person with white eyes."[12] Following contact with Europeans, the Crow suffered smallpox epidemics, reducing their population drastically.

The first treaty signed between the United States and the Crow was signed by Chief Long Hair in 1825; however, Chief Sore Belly refused to sign.[6]

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 confirmed a large area centered on the Big Horn Mountains as Crow lands—the area ran from the Big Horn Basin on the west, to the Musselshell River on the north, and east to the Powder River, and included the Tongue River basin.[14] However, for two centuries, the Cheyenne and many bands of Lakota had been steadily migrating westward across the plains, and by 1851 they were established just to the south and east of Crow territory in Montana.[15] These tribes coveted the fine hunting lands of the Crow and conducted tribal warfare against them, pushing the less numerous Crow to the west and northwest along the Yellowstone, although the Crow defended themselves, often successfully.

During the period of the Indian Wars, the Crow supported the United States military by supplying scouts and protecting travelers on the Bozeman Trail. Chief Plenty Coups encouraged this, believing that the Americans would win the war and would remember their Crow allies, ensuring their survival in the white man's world.[16]

Red Cloud's War (1866 to 1868) was a challenge by the Lakota Sioux to the military presence on the Bozeman Trail, which went to the Montana gold fields along the eastern edge of the Big Horn Mountains. Red Cloud's War ended in a victory for the Lakota Sioux, and the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie confirmed their control over all the high plains from the crest of the Big Horn Mountains eastward across the Powder River Basin to the Black Hills.[17] Thereafter bands of Lakota Sioux led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and others, along with their Northern Cheyenne allies, hunted and raided throughout the length and breadth of eastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming - ancestral Crow territory. Although early in the war on June 25, 1876 the Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne enjoyed a major victory over army forces under General George A. Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Great Sioux War (1876 - 1877) ended in the defeat of the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies, and their exodus from eastern Montana and Wyoming, either in flight to Canada or by forced removal to distant reservations.

Despite their support of the U.S. military, the Crow were treated no differently than the other tribes, being forced to cede much of their land and by 1888 were settled on their reservation.[16] Chief Plenty Coups made many trips to Washington D.C., where he fought against the U.S. senators' plans to abolish the Crow nation and take away their lands. Although they were forced onto a reservation, he succeeded in keeping part of the Crows' original land when many other Native Americans tribes had been relocated to reservations on entirely different land than where they had lived their lives. Chief Plenty Coups was was chosen as the representative American Indian to participate in the dedication of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, DC in 1921. He laid his war bonnet and coup stick at the tomb.[18]

Culture

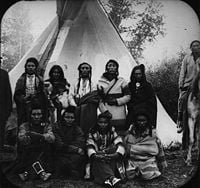

The Crow were a nomadic people. Their traditional shelters are tipis made with bison skins and wooden poles. The Crow are known to construct some of the largest tipis—they could house as many as 40 people, the average being around 12.[19] Inside the tipi are mattresses arranged around the border of the tipi, and a fireplace in the center. The smoke from the fire escapes through a hole in the top of the tipi. Many Crow families still own and use a tipi, especially when traveling.

Traditional clothing worn by the Crow depends on gender. Women tended to wear simple clothes. They wore dresses made of mountain sheep or deer skins, decorated with elk teeth. They covered their legs with leggings and their feet with moccasins. Crow women had short hair, unlike the men. Male clothing usually consisted of a shirt, trimmed leggings with a belt, a robe, and moccasins. Their hair was long, in some cases reaching or dragging the ground, and was sometimes decorated.

The Crows' main source of food was bison, but they also hunted mountain sheep, deer, and other game. Buffalo meat was often roasted or boiled in a stew with prairie turnips. The rump, tongue, liver, heart, and kidneys all were considered delicacies. Dried bison meat was ground with fat and berries to make pemmican.

The Crow had more horses than any other plains tribe, in 1914 they numbered approximately thirty to forty thousand but by 1921 had dwindled to just one thousand. They also had numerous dogs, but unlike some other tribes, they did not eat their dogs.

Kinship system

The Crow were a matrilineal (descent through the maternal line), matrilocal (husband moves to the wife's mothers house upon marriage), and matriarchal tribe (females obtaining high status, even chief). Women held a very significant role within the tribe.

Crow kinship is a matrilineal kinship system used to define family. The Crow system is one of the six major kinship systems (Eskimo, Hawaiian, Iroquois, Crow, Omaha, and Sudanese) identified by Lewis Henry Morgan in his 1871 work Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. The Crow system is distinctive because unlike most other kinship systems, it chooses not to distinguish between certain generations. The system also distinguishes between the mother's side and the father's side. The relatives of the subject's father's matrilineage are distinguished only by their gender, regardless of their age or generation. In contrast, differences of generation are noted on the mother's side. This system is associated with groups that have a strong tradition of matrilineal descent.

Mythology

The medicine man of the tribe was known as an Akbaalia ("healer").[7]

The Mannegishi are bald humanoids with large eyes and tiny bodies. They were tricksters and may be similar to fairies. They have supposedly been sighted in Massachusetts and are known there as Dover Demons.

Baaxpee is a spiritual power that can cause a person to mature, as well as unusual events or circumstances that force maturation. After transformation, the changed are known as Xapaaliia. Andiciopec is a warrior hero who is invincible to bullets.

Contemporary Crow

The Crow of Montana are a federally recognized Indian tribe. The Crow Indian Reservation in south-central Montana is a large reservation covering 9,307.269 km² (3,593.557 sq mi) of land area, the fifth-largest Indian reservation in the United States and the largest in Montana. It encompasses upland plains, the Wolf, Bighorn and Pryor Mountains, and the bottomlands of the Bighorn River, Little Bighorn River, and Pryor Creek. The reservation is home to 8,143 (71.7 percent) of the 11,357 enrolled Apsáalooke tribal members.[20]

Government

The Seat of Government and Capital is Crow Agency, Montana. Prior to the 2001 Constitution, the Crow Nation was governed by the 1948 Constitution which organized the tribe as a General Council (Tribal Council). It was comprised of all enrolled adult members (females 18 years or older and males 21 or older) of the Crow Nation. The General Council was a direct democracy, comparable to that of ancient Athens. The Crow Nation established a three branch government at a 2001 Council Meeting: the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches, for the governance of the Crow Tribe. In reality, the General Council has not convened since the establishment of the 2001 constitution.

The Crow Nation has traditionally elected a Chairperson of the Crow Tribal Council biennially. However, in 2001, the term of office was extended from two to four years. The Chairperson serves as chief executive officer, speaker of the council, and majority leader of the Crow Tribal Council. Notable Chairs have been Clara Nomee, Edison Real Bird, and Robert "Robie" Yellowtail. The Chief Judge of the Crow Nation is Angela Russell.

Language

According to Ethnologue, with figures from 1998, 77 percent of Crow people over 66 years old speak the language; "some" parents and older adults, "few" high school students and "no pre-schoolers" speak Crow. Eighty percent of the Crow Nation prefers to speak in English.[5]

However, Graczyk claims in his A Grammar of Crow published in 2007, that "[u]nlike many other native languages of North America in general, and the northern plain in particular, the Crow language still exhibits considerable vitality: there are fluent speakers of all ages, and at least some children are still acquiring Crow as their first language." Many of the younger population who do not speak Crow are able to understand it. Almost all of those who do speak Crow are also bilingual in English.[4] Graczyk cites the reservation community as the reason for both the high level of bilingual Crow-English speakers and the continued use and prevalence of the Crow language.

Crow Fair

The tribe has hosted a large Crow Fair, a celebration of dance, rodeo, and parade annually for over a hundred years. Held on the third week of August on land surrounding the Little Big Horn River near Billings, Montana, it is the largest and most spectacular of Indian celebrations in the Northern Plains.[21] Crow Fair has been described as the "Teepee Capital of the World" because of the approximately 1,200 to 1,500 teepees in the encampment during the week of the celebration.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Official Site of the Crow Tribe Apsáalooke Nation, About the Apsáalooke Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The Crow Society, Crow The People Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Shirley Silver and Wick R. Miller, American Indian Languages: Cultural and Social Contexts (Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0816521395), 367.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Randolph Graczyk, A Grammar of Crow (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0803221963).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ethnologue Crow Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Little Big Horn College, Apsáalooke Historical Timeline The Apsáalooke (Crow Indians) of Montana Tribal Histories. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rodney Frey, The World of the Crow Indians: As Driftwood Lodges (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0806125602)

- ↑ Barney Old Coyote, Turtle Island Storyteller Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Women of the Fur Trade, The Dog Travois Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Alan J. Osborn, “Ecological Aspects of Equestrian Adapation in Aboriginal North America.” American Anthropologist 85(3) (Sept 1983): 566.

- ↑ Phenocia Bauerle, The Way of the Warrior: Stories of the Crow People (University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0803262300)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 John Doerner, Road to Little Bighorn Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ↑ Four Directions Institute, Crow Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Charles J. Kappler (ed.), Article 5 Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Mark H. Brown, The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone: A History of the Yellowstone Basin (Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0803250260), 128–129.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744), 86-88.

- ↑ Charles J. Kappler (ed.), Treaty with the Sioux-Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee-and Arapaho, 1868 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904). Retrieved December 2, 2011. See Article 16, creating unceded Indian Territory east of the summit of the Big Horn Mountains and north of the North Platte River.

- ↑ Arlington National Cemetery website, The Unknown Soldier of World War I State Funeral. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ↑ Barry Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 019513897x)313-316.

- ↑ Official site of the Crow Tribe Apsáalooke Nation, American Indian and Total Population for Crow Reservation and Related Areas Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Crow Fair. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ Montana Official State Travel Site, Crow Fair and Rodeo Retrieved December 2, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Frey, Rodney. The World of the Crow Indians: As Driftwood Lodges. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0806125602

- Graczyk, Randolph. A Grammar of Crow. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0803221963

- Matthews, G.H. "Glottochronology and the separation of the Crow and Hidatsa," Symposium on the Crow-Hidatsa Separations, Archaeology in Montana 20(3) (1979): 113-125.

- Morgan, Lewis H. Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1997 (original 1871). ISBN 978-0803282308

- Pritzker, Barry. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 019513897x

- Silver, Shirley, and Wick R. Miller. American Indian Languages: Cultural and Social Contexts. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0816521395

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Wood, W. Raymond, and Margot Liberty (eds.). Anthropology on the Great Plains. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0803247086

- The Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1983, paperback, ISBN 0-8032-7909-4

- Stories That Make the World: Oral Literature of the Indian Peoples of the Inland Northwest. As Told by Lawrence Aripa, Tom Yellowtail and Other Elders. Rodney Frey, edited. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1995, paperback, ISBN 0-8061-3131-4

- The Crow and the Eagle: A Tribal History from Lewis & Clark to Custer, Keith Algier, Caxton Printers, Caldwell, Idaho, 1993, paperback, ISBN 0-87004-357-9

- From The Heart Of The Crow Country: The Crow Indians' Own Stories, Joseph Medicine Crow, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2000, paperback, ISBN 0-8032-8263-X

- Apsaalooka: The Crow Nation Then and Now, Helene Smith and Lloyd G. Mickey Old Coyote, MacDonald/Swãrd Publishing Company, Greensburg, Pennsylvania, 1992, paperback, ISBN 0-945437-11-0

- Parading through History: The Making of the Crow Nation in America 1805-1935, Frederick E. Hoxie, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1995, hardcover, ISBN 0-521-48057-4

- The Handsome People: A History of the Crow Indians and the Whites, Charles Bradley, Council for Indian Education, 1991, paperback, ISBN 0-89992-130-2

- Myths and Traditions of the Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, AMS Press, 1980, hardcover, ISBN 0-404-11872-0

- Social Life of the Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, AMS Press, 1912, hardcover, ISBN 0-404-11875-5

- Material Culture of the Crow Indians, Robert H Lowie, The Trustees, 1922, hardcover, ASIN B00085WH80

- The Tobacco Society of the Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, The Trustees, 1919, hardcover, ASIN B00086IFRG

- Religion of the Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, The Trustees, 1922, hardcover, ASIN B00086IFQM

- The Crow Sun Dance, Robert Lowie, 1914, hardcover, ASIN B0008CBIOW

- Minor Ceremonies of the Crow Indians, Robert H. Lowie, American Museum Press, 1924, hardcover, ASIN B00086D3NC

- Crow Indian Art, Robert H. Lowie, The Trustees, 1922, ASIN B00086D6RK

- The Crow Language, Robert H. Lowie, University of California press, 1941, hardcover, ASIN B0007EKBDU

- The Way of the Warrior: Stories of the Crow People, Henry Old Coyote and Barney Old Coyote, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2003, ISBN 0-8032-3572-0

- Two Leggings: The Making of a Crow Warrior, Peter Nabokov, Crowell Publishing Co., 1967, hardcover, ASIN B0007EN16O

- Plenty-Coups: Chief of the Crows, Frank B. Linderman, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1962, paperback, ISBN 0-8032-5121-1

- Pretty-shield: Medicine Woman of the Crows, Frank B. Linderman, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 1974, paperback, ISBN 0-8032-8025-4

- They Call Me Agnes: A Crow Narrative Based on the Life of Agnes Yellowtail Deernose, Fred W. Voget and Mary K. Mee, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1995, hardcover, ISBN 0-8061-2695-7

- Yellowtail, Crow Medicine Man and Sun Dance Chief: An Autobiography, Michael Oren Fitzgerald, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1991, hardcover, ISBN 0-8061-2602-7

- Grandmother's Grandchild: My Crow Indian Life, Alma Hogan Snell, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2000, hardcover, ISBN 0-8032-4277-8

- Memoirs of a White Crow Indian, Thomas H. Leforge, The Century Co., 1928, hardcover, ASIN B00086PAP6

- Radical Hope. Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, Jonathan Lear, Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-674-02329-3

External links

- Crow Tribal website

- Crow Tribal Council Website

- 2001 Constitution

- 1948 Constitution

- A few images from photo exhibition on Crow Indians, with short account of 21st century lifestyle

- Collection of Historical Crow Photographs

- Crow Ethnologue

- Crow Language on the Native Languages of the Americas site

- Crow Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Montana United States Census Bureau

- The Apsáalooke (Crow Indians) of Montana Tribal Histories

- Native Spirit and the Sun Dance Way - the words of Thomas Yellowtail, a Crow Medicine Man and Sun Dance chief are brought to life by actor Gordon Tootoosis as he describes and explains the ancient Sun Dance ceremony sacred to the Crow tribe.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.