Difference between revisions of "Coca" - New World Encyclopedia

(applied ready tag) |

|||

| (144 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

{{Taxobox | {{Taxobox | ||

| color = lightgreen | | color = lightgreen | ||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| familia = [[Erythroxylaceae]] | | familia = [[Erythroxylaceae]] | ||

| genus = ''[[Erythroxylum]]'' | | genus = ''[[Erythroxylum]]'' | ||

| − | | | + | |subdivision_ranks = Species |

| − | + | |subdivision = | |

| − | | | + | *''[[Erythroxylum coca]]'' |

| + | **''E. coca'' var. ''coca'' | ||

| + | **''E. coca'' var. ''ipadu'' | ||

| + | *''[[Erythroxylum novogranatense]]'' | ||

| + | **''E. novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' | ||

| + | **''E. novogranatense'' var. ''truxillense'' | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''Coca''' is the common name for four domesticated varieties of tropical [[plant]]s belonging to the two [[species]] ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''E. novogranatense'', whose [[leaf|leaves]] are used for a variety of purposes, including serving as the source of the drug [[cocaine]]. The four varieties are ''E. coca'' var. ''coca'' (Bolivian or Huánuco coca), ''E. coca'' var. ''ipadu'' (Amazonian coca), ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' (Colombian coca), and ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''truxillense'' (Trujillo coca). The plant, which is native to the [[Andes Mountains]] and [[Amazon]] of [[South America]], now also is grown in limited quantities in other regions with tropical climates. | ||

| − | + | Coca is particularly renowned worldwide for its psychoactive [[alkaloid]], cocaine. While the alkaloid content of coca leaves is low, when the leaves are processed they can provide a concentrated source of cocaine. This purified form, which is used nasally, smoked, or injected, can be very addictive and have deleterious impacts on the [[brain]], [[heart]], [[respiratory system]], [[kidney]]s, sexual system, and [[gastrointestinal tract]]. It can create a cycle where the user has difficulty experiencing pleasure without the drug. | |

| − | + | For the plant, cocaine seems to serve a valuable function as an effective insecticide, limiting damage from herbivorous insects. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The coca leaves have been used unprocessed for thousands of years in South America for various [[religion|religious]], social, [[medicine|medicinal]], and [[nutrition|nutritional]] purposes, including to control hunger and combat the impacts of high altitudes. It has been called the "divine plant of the Incas." Unprocessed coca leaves are also commonly used in the Andean countries to make a [[herbal tea]] with mild [[stimulant]] effects. However, since the alkaloid cocaine is present in only trace amounts in the leaves, it does not cause the euphoric and psychoactive effects associated with use of the drug. Cocaine is available as a prescription for such purposes as external application to the [[skin]] to numb [[pain]]. | ||

| − | The | + | The Coca-Cola company uses a cocaine-free coca extract. In the early days of the manufacture of Coca-Cola beverage, the formulation did contain some cocaine, although within a few years of its introduction it already was only trace amounts. |

| − | + | ==Species and varieties== | |

| + | [[File:Colcoca01.jpg|thumb|right|225px|Coca shrub in Colombia]] | ||

| + | There are two species of cultivated coca, each with two varieties: | ||

| + | *''[[Erythroxylum coca]]'' | ||

| + | **''Erythroxylum coca'' var. ''coca'' (Bolivian or [[Huánuco]] coca) - well adapted to the eastern [[Andes]] of Peru and Bolivia, an area of humid, tropical, [[montane forest]]. | ||

| + | **''Erythroxylum coca'' var. ''ipadu'' (Amazonian coca) - cultivated in the lowland [[Amazon Basin]] in Peru and Colombia. | ||

| + | *''[[Erythroxylum novogranatense]]'' | ||

| + | **''Erythroxylum novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' (Colombian coca) - a highland variety that is utilized in lowland areas. It is cultivated in drier regions found in Colombia. However, ''E. novogranatense'' is very adaptable to varying ecological conditions. | ||

| + | **''Erythroxylum novogranatense'' var. ''truxillense'' ([[Trujillo Province, Peru|Trujillo]] coca) - grown primarily in Peru and Colombia. | ||

| − | + | All four of the cultivated cocas were domesticated in pre-Columbian times and are more closely related to each other than to any other species (Plowman 1984). ''E. novogranatense'' was historically seen as a variety or subspecies of ''E. coca'' (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). The two subspecies of ''[[Erythroxylum coca]]'' are almost indistinguishable phenotypically. ''[[Erythroxylum novogranatense]]'' var. ''novogranatense'' and ''[[Erythroxylum novogranatense]]'' var. ''truxillense'' are phenotypically similar, but morphologically distinguishable. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Under the older [[Cronquist system]] of classifying [[flowering plant]]s, coca was placed in an [[order (biology)|order]] [[Linales]]; more modern systems place it in the order [[Malpighiales]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Wild populations of ''[[Erythroxylum coca]]'' var. ''coca'' are found in the eastern [[Andes]]; the other 3 [[taxon|taxa]] are only known as cultivated plants. | |

| − | + | ==Description== | |

| + | [[Image:Colcoca03.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Leaves and branches of ''E. coca'']] | ||

| + | Coca plants tend to be evergreen [[shrub]]s with straight, reddish branches. This later quality is reflected in the name of the [[genus]], ''Erythroxylum'', which is a combination of the [[Greek]] ''erythros'', meaning "red," and ''xylon'', meaning "wood" (Mazza 2013). The coca plants tend to have oval to elliptical green leaves tapering at the ends, small yellowish-green [[flower]]s with [[heart]]-shaped anthers, and [[fruit]]s in the form of red drupes with a single [[seed]]. | ||

| − | + | The coca plant is largely an understory species, found in moist tropical forests. It is native to the eastern Andes slopes and the Amazon. It does well at high elevations, being cultivated in [[Bolivia]] at elevations of 1000 to 2000 meters, but it also is cultivated at lower elevations, including lowland rainforests (Boucher 1991). | |

| − | The | + | ====''Erythroxylum coca''==== |

| + | The wild ''E. coca'' commonly reaches a height of about 3 to 5.5 meters (12-18 ft), whereas the domestic plant is usually kept to about 2 meters (6 ft). The stem reaches about 16 centimeters in diameter and has a whitish bark. The branches are reddish, straight, and alternate. There is perennial renewal of the branches in a geometrical progression after being cut (de Medeiros and Rahde 1989). | ||

| − | + | The leaves of ''E. coca'' are green or greenish brown, smooth, opaque, and oval or elliptical, and generally about 1.5 to 3 centimeters (0.6-1.2 inches) wide and reach to 11 centimeters (4.3 inches) long. A special feature of the leaf is that the areolate portion is bordered by two curved, longitudinal lines, with one on either side of the midrib and more pronounced on the underside of the leaf. The small yellowish-green flowers give way to red berries, which are drupaceous and oblong, measuring about 1 centimeter (0.4 inches), and with only one seed (de Medeiros and Rahde 1989). | |

| − | + | While both ''E. coca'' var. ''coca'' and ''E. coca'' var. ''ipadu'' have leaves that are broadly elliptical, the ''ipadu'' variety tends to have a more rounded apex versus the more pointed variety ''coca'' (DEA 1993). | |

| − | === | + | ====''Erythroxylum novogranatense''==== |

| − | + | [[Image:Erythroxylum novogranatense var. Novogranatense (retouched).jpg|right|thumb|250px|5-year-old ''E. novogranatense var novogranatense'']] | |

| + | ''E. novogranatense'' grows to about 3 meters (10 feet), with leaves that are bright green, alternate, obovate or oblong-elliptic and on about a 0.5 centimeter (0.2 in) long petiole. The leaves are about 2 to 6 centimeters (0.8-2.4 in) long and 1 to 3 centimeters (0.4-1.2 in) broad. The flowers are hermaphrodite, solitary or grouped, axillary, and with five yellowish, white petals, about 0.4 centimeters (0.16 in) long and 0.2 centimeters (0.08 in) wide. The fruits are drupes, of oblong shape and red color, with only one oblong seed. They get to be about 0.8 centimeters (0.3 in) long and 0.3 centimeters (0.1 in) in diameter (Mazza 2013). | ||

| − | + | The leaf of ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' tends to have a paler green color, more rounded apex, and be somewhat thinner and narrower than the leaf of ''E. coca'' (DEA 1993). | |

| − | + | ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''truxillense'' is very similar to ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' but differs in that the latter has longitudinal lines on either side of the central nervation (as with ''E. coca'') while this is lacking in the ''truxillense'' variety (Mazza 2013). | |

| − | The | + | The species name comes from ''novus, a, um'', meaning "new," and ''granatensis'', meaning "of Granada," from the name "Nueva Granada," the name that Colombia was called at the time of the Spanish conquest (Mazza 2013). |

| − | + | ==Cocaine and other alkaloids== | |

| + | The coca plant has many [[alkaloid]]s, such as cocaine. Alkaloids are chemical compounds that are naturally occurring and contain mostly basic [[nitrogen]] atoms. Well-known alkaloids include [[caffeine]] found in the seed of the [[coffee]] plant and the leaves of the tea bush; [[nicotine]] found in the nightshade family of plants including the [[tobacco plant]] (''Nicotiana tabacum''); [[morphine]] found in [[poppy|poppies]]; and theobromine found in the cacao plant. Other well-known alkaloids include mescaline, strychnine, quinine, and codeine. | ||

| − | + | Among the about 14 diverse alkaloids identified in the coca plant are [[ecgonine]], [[hygrine]], truxilline, benzoylecgonine, and tropacocaine. Coca leaves have been reported as having 0.5 to 1.5% alkaloids by dry weight (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The most concentrated alkaloid is cocaine (cocaine (methyl benzoyl ecgonine or benzoylmethylecgonine). Concentrations vary by variety and region, but leaves have been reported variously as between 0.25% and 0.77% (Plowman and Rivier 1983), between 0.35% and 0.72% by dry weight (Nathanson et al. 1993), and between 0.3% and 1.5% and averaging 0.8% in fresh leaves (Casale and Klein 1993). ''E. coca'' var. ''ipadu'' is not as concentrated in cocaine alkaloids as the other three varieties (DEA 1993). Boucher (1991) reports that the coca leaves from Bolivia, while considered to be of higher quality by traditional users, have lower concentrations of cocaine than leaves from the Chapare Valley. He also reports those leaves with smaller amounts of cocaine have traditionally been preferred for chewing, being associated with a sweet or less bitter taste, while those preferred for the drug trade prefer those leaves with a greater alkaloid content. | |

| − | + | For the plant, cocaine is believed to serve as a naturally occurring insecticide, with the alkaloid exerting such effects at concentrations normally found in the leaves (Nathanson et. al. 1993). It has been observed that compared to other tropical plants, coca seems to be relatively pest free, with little observed damage to the leaves and rare observations of herbivorous [[insect]]s on plants in the field (Nathanson et al. 1993). | |

| − | + | ==Cultivation== | |

| + | [[Image:Colcoca02.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Leaves of ''E. coca'']] | ||

| + | [[Image:Colcoca04.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Leaves and fruit of ''E. coca'']] | ||

| − | + | Ninety-eight percent of the global land area plant with coca is in the three nations of [[Colombia]], [[Peru]], and [[Bolivia]] (Dion and Russler 2008). However, while it is, or has been grown, in other nations, including [[Taiwan]], [[Indonesia]], [[Formosa]], [[India]], [[Java]], [[Ivory Coast]], [[Ghana]], and [[Cameroon]], coca cultivation has largely been abandoned outside South America since the mid 1900s (Boucher, 1991; Royal Botanic Gardens 2013). The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimated, in a 2011 report, that in 2008 Colombia was responsible for about half of global production of coca, while Peru contributed over one-third, and Bolivia the rest, although coca leaf production in Colombia has been declining over the past ten years while that of Peru has been increasing and by 2009 they may have reach similar output levels (UNODC 2011). | |

| − | + | ''E. coca'' var. ''coca'' (Bolivian or [[Huánuco]] coca) is the most widely grown variety and is cultivated is the eastern slopes of the Andes, from Bolivia in the south through Peru to Ecuador in the north. It tends mostly to be cultivated in Bolivia and Peru, and largely between 500 meters to 1500 meters (1,650-4,950 feet). ''E. coca'' var. ''ipadu'' (Amazonian coca) is found in the Amazon basin, in southern Colombia, northeastern Peru, and western [[Brazil]]. It tends mostly to be cultivated in Peru and Colombia. ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''novogranatense'' (Colombian coca) thrives in Colombia and is grown to some extent in Venezuela. ''E. novogranatense'' var. ''truxillense'' ([[Trujillo Province, Peru|Trujillo]] coca) is largely cultivated in Peru and Colombia; this variety is grown to 1500 meters (DEA 1993). | |

| − | + | While locations that are hot, damp, and humid are particularly conducive to growth of coca plants, the leaves with the highest concentrations of cocaine tend to be found among those grown at higher, cooler, and somewhat drier altitudes. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Coca plants are grown from [[seed]]s that are collected from the [[drupe]]s when ripe. The seeds are allowed to dry and then placed in seed beds, typically sheltered from the sun, and germinate in about 3 weeks. The plants are transplanted to prepared fields when they reach about 30 to 60 centimeters in height, which is about 2 months of age. Plants can be harvested 12 to 24 months after being transplanted (Casale and Klein 1993; DEA 1993). | |

| − | + | Although the plants grow to more than 3 meters, the cultivated coca plants are typically pruned to 1 to 2 meters to ease harvest. Likewise, although the plants can live up to 50 years, they often are uprooted or cut back to near ground level after 5 to 10 years because of concern about decreasing cocaine content in the older shrubs (Casale and Klein 1993; DEA 1993). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Leaves are harvested year round. Harvesting is mainly of new fresh growth. The leaves are dried in the sun and then packed for distribution; leaves are kept dry in order to preserve the leaf quality. | |

| − | == | + | ==History== |

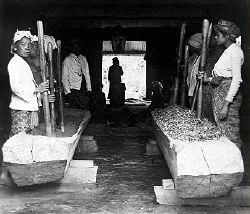

| − | + | [[File:Arbeiders die cocabladeren fijnstampen op Java.jpg|thumb|250px|Workers in [[Java]] prepared coca leaves. This product was mainly traded in [[Amsterdam]], and was further processed into cocaine. ([[Dutch East Indies]], before 1940.)]] | |

| − | + | There is [[archaeology|archeological]] evidence that suggests the use of coca leaves 8000 years ago, with the finding of coca leaves of that date (6000 B.C.E.) in floors in [[Peru]], along with pieces of calcite (calcium carbonate), which is used by those chewing leaves to bring out the alkaloids by helping dissolve them into the saliva (Boucher 1991). Coca leaves also have been found in the Huaca Prieta settlement in northern Peru, dated from about 2500 to 1800 B.C.E. (Hurtado 1995). Traces of cocaine also have been in 3000-year-old mummies of the Alto Ramirez culture of Northern Chile, suggesting coca-leaf chewing dates to at least 1500 B.C.E. (Rivera et al. 2005). The remains of coca leaves not only have been found with ancient Peruvian mummies, but pottery from the time period depicts humans with bulged cheeks, indicating the presence of something on which they are chewing (Altman et al. 1985). It is the view of Boucher (1991) that the coca plant was domesticated by 1500 B.C.E. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | In the [[pre-Columbian era]], coca was a main part of the economic system and was exchanged for [[fruit]]s and [[fur]]s from the Amazon, [[potato]]es and [[grain]]s from the Andean highlands, and [[fish]] and shells from the Pacific (Boucher 1991). The use of coca for currency continued during the Colonial Period because it was considered even more valuable than silver or gold. Uses of coca in the early times include use for curing aliments, providing energy, making religious offerings, and forecasting of events (Hurtado 2010). | |

| − | + | {{readout||right|250px|The coca plant has been called the "divine plant of the [[Incas]]"}} | |

| − | + | Coca chewing may originally have been limited to the eastern Andes before its introduction to the Incas. As the plant was viewed as having a divine origin, its cultivation became subject to a state monopoly and its use restricted to nobles and a few favored classes (court orators, couriers, favored public workers, and the army) by the rule of the [[Topa Inca]] (1471–1493). As the Incan empire declined, the leaf became more widely available. After some deliberation, [[Philip II of Spain]] issued a decree recognizing the drug as essential to the well-being of the Andean Indians but urging missionaries to end its religious use. The Spanish are believed to have effectively encouraged use of coca by an increasing majority of the population to increase their labor output and tolerance for starvation, but it is not clear that this was planned deliberately. | |

| − | + | Coca was first introduced to Europe in the sixteenth century. However, coca did not become popular until the mid-nineteenth century, with the publication of an influential paper by Dr. [[Paolo Mantegazza]] praising its stimulating effects on cognition. This led to invention of [[coca wine]] and the first production of pure cocaine. | |

| − | + | The cocaine alkaloid was first isolated by the German [[chemist]] [[Friedrich Gaedcke]] in 1855. Gaedcke named the alkaloid "erythroxyline", and published a description in the journal ''Archiv der Pharmazie'' (Gaedcke 1855). Cocaine also was isolated in 1859 by [[Albert Niemann (chemist)|Albert Niemann]] of the [[University of Göttingen]], using an improved purification process (Niemann 1860). It was Niemann who named coca's chief alkaloid "cocaine" (Inciardi 1992). | |

| − | + | Coca wine (of which [[Vin Mariani]] was the best-known brand) and other coca-containing preparations were widely sold as patent medicines and tonics, with claims of a wide variety of health benefits. The original version of [[Coca-Cola]] was among these, although the amount in Coca-Cola may have been only trace amounts. Products with cocaine became illegal in most countries outside of South America in the early twentieth century, after the addictive nature of cocaine was widely recognized. | |

| − | In [[ | + | In the early twentieth century, the Dutch colony of [[Java]] became a leading exporter of [[coca leaf]]. By 1912, shipments to Amsterdam, where the leaves were processed into cocaine, reached 1 million kg, overtaking the Peruvian export market. Apart from the years of the First World War, Java remained a greater exporter of coca than Peru until the end of the 1920s (Musto 1998). As noted above, since the mid-1900s, coca cultivation outside South America has virtually been abandoned. |

| − | + | ===International prohibition of coca leaf=== | |

| + | As the raw material for the manufacture of the recreational [[psychoactive drug|drug]] cocaine, the coca leaf has been the target of international efforts to restrict its cultivation in an attempt to prevent the production of cocaine. While the cultivation, sale, and possession of unprocessed coca leaf (but not of any processed form of cocaine) is generally legal in the countries where traditional use is established—such as Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina—cultivation even in these countries is often restricted. In the case of Argentina, it is legal only in some northern provinces where the practice is so common that the state has accepted it. | ||

| − | + | The prohibition of the use of the coca leaf except for medical or scientific purposes was established by the [[United Nations]] in the 1961 [[Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs]]. The coca leaf is listed on [[Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs#Schedules of drugs|Schedule I]] of the 1961 Single Convention together with cocaine and heroin. The Convention determined that "The Parties shall so far as possible enforce the uprooting of all coca bushes which grow wild. They shall destroy the coca bushes if illegally cultivated" (Article 26), and that "coca leaf chewing must be abolished within twenty-five years from the coming into force of this Convention" (Article 49, 2.e). The Convention recognized as an acceptable use of the coca leaves for preparing a flavoring agent without the alkaloids, and import, export, trade, and possession of the leaves for such purpose. However, the Convention also noted that whenever prevailing conditions render prohibition of cultivation the most suitable measure for preventing diversion of the crop into the illicit drug trade and for protection of health and general welfare, then the nation "shall prohibit cultivation" (UN 1961). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | Despite the legal restriction among countries party to the international treaty, coca chewing and drinking of coca tea is carried out daily by millions of people in the Andes as well as considered sacred within indigenous cultures. In recent times, the governments of several South American countries, such as Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela, have defended and championed the traditional use of coca, as well as the modern uses of the leaf and its extracts in household products such as teas and toothpaste. |

| − | {{ | + | |

| − | + | In an attempt to obtain international acceptance for the legal recognition of traditional use of coca in their respective countries, Peru and Bolivia successfully led an amendment, paragraph 2 of Article 14 into the 1988 [[United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances]], stipulating that measures to eradicate illicit cultivation and to eliminate illicit demand "should take due account of traditional licit use, where there is historic evidence of such use" (UNDC 2008). | |

| + | |||

| + | Bolivia also made a formal reservation to the 1988 Convention. This convention required countries to adopt measures to establish the use, consumption, possession, purchase or cultivation of the coca leaf for personal consumption as a criminal offense. Bolivia stated that "the coca leaf is not, in and of itself, a narcotic drug or psychotropic substance" and stressed that its "legal system recognizes the ancestral nature of the licit use of the coca leaf, which, for much of Bolivia's population, dates back over centuries" (UNDC 2008). | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, the [[International Narcotics Control Board]] (INCB)—the independent and [[quasi-judicial]] control organ for the implementation of the United Nations drug conventions—denied the validity of article 14 in the 1988 Convention over the requirements of the 1961 Convention, or any reservation made by parties, since it does not "absolve a party of its rights and obligations under the other international drug control treaties" (UNDC 2008; INCB 2007). The INCB considered Bolivia, Peru, and a few other countries that allow such practices as coca-chewing and drinking of coca tea to be in breach with their treaty obligations, and insisted that "each party to the Convention should establish as a criminal offence, when committed intentionally, the possession and purchase of coca leaf for personal consumption" (INCB 2007). The INCB noted in its 1994 Annual Report that "mate de coca, which is considered harmless and legal in several countries in South America, is an illegal activity under the provisions of both the 1961 Convention and the 1988 Convention, though that was not the intention of the plenipotentiary conferences that adopted those conventions." The INCB also implicitly dismissed the original report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf by recognizing that "there is a need to undertake a scientific review to assess the coca-chewing habit and the drinking of coca tea."(INCB 1994). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In reaction to the 2007 Annual Report of the INCB, the Bolivian government announced that it would formally issue a request to the United Nations to unschedule the coca leaf of List 1 of the 1961 UN Single Convention. Bolivia led a diplomatic effort to do so beginning in March 2009. In that month, the Bolivian President, Evo Morales, went before the United Nations and relayed the history of coa use for such purposes as medicinal, nutritional, social, and spiritual, and he at that time put a leaf in his mouth (Cortes 2013). However, Bolivia's effort to have the coca leaf removed from the List 1 of the 1960 UN Single Convention was unsuccessful, when eighteen countries objected to the change before the January 2011 deadline. A single objection would have been sufficient to block the modification. The legally unnecessary step of supporting the change was taken formally by Spain, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Costa Rica. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In June 2011, Bolivia moved to denounce the 1961 Convention over the prohibition of the coca leaf. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On January 1, 2012 Bolivia's withdrawal from the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs came into effect. However, Bolivia took steps to again become a party to the 1961 Single Convention conditional on the acceptance of a reservation on the chewing of coca leaf. For this reservation not to pass, one-third of the 183 States party to this convention would have had to object within one year after the proposed reservation was submitted. This deadline expired on January 10, 2013, with only 15 countries objecting to Bolivia's reservation, thus permitting the reservation, and Bolivia's re-accession to the Convention came into force on January 10, 2013 (UNODC 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Currently, outside of South America, most countries' laws make no distinction between the coca leaf and any other substance containing cocaine, so the possession of coca leaf is prohibited. In South America, coca leaf is illegal in both Paraguay and Brazil. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the Netherlands, coca leaf is legally in the same category as cocaine, both are List I drugs of the [[Opium Law]]. The Opium Law specifically mentions the leafs of the plants of the genus ''Erythroxylon''. However, the possession of living plants of the genus ''Erythroxylon'' are not actively prosecuted, even though they are legally forbidden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the United States, a [[Stepan Company]] plant in [[Maywood, New Jersey]] is a registered importer of coca leaf. The company manufactures pure cocaine for medical use and also produces a cocaine-free extract of the coca leaf, which is used as a flavoring ingredient in Coca-Cola. Other companies have registrations with the DEA to import coca leaf according to 2011 Federal Register Notices for Importers (ODC 2011), including Johnson Matthey, Inc, Pharmaceutical Materials; Mallinckrodt Inc; Penick Corporation; and the Research Triangle Institute. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Uses== | ||

| + | [[File:Folha de coca.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Man holding coca leaf in Bolivia]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Recreational psychoactive drug=== | ||

| + | {{main|cocaine}} | ||

| + | Coca leaf is the raw material for the manufacture of the psychoactive drug cocaine, a powerful stimulant extracted chemically from large quantities of coca leaves. Cocaine is best known worldwide for such illegal use. This concentrated form of cocaine is used ''nasally'' (nasal insufflation is also known as "snorting," "sniffing," or "blowing" and involves absorption through the mucous membranes lining the sinuses), ''injected'' (the method that produces the highest blood levels in the shortest time), or ''smoked'' (notably the cheaper, more potent form called "crack"). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Use of concentrated cocaine yields pleasure through its interference with [[neurotransmitter]]s, blocking the neurotransmitters, such as [[dopamine]], from being reabsorbed, and thus resulting in continual stimulation. However, such drug use can have deleterious impacts on the [[brain]], [[heart]], [[respiratory system]], [[kidney]]s, sexual system, and [[gastrointestinal tract]] (WebMD 2013a). For example, it can result in a heart attack or strokes, even in young people,and it can cause ulcers and sudden kidney failure, and it can impair sexual function (WebMD 2013a). It also can be highly addictive, creating intense cravings for the drug, and result in the cocaine user becoming "in a very real sense, unable to experience pleasure without the drug" (Marieb and Hoehn 2010). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimated that in 2009, the US cocaine market was $37 billion (and shrinking over the past ten years) and the West and Central European Cocaine market was US$ 33 billion (and increasing over the past ten years) (USODC 2011). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The production, distribution and sale of cocaine products is restricted and/or illegal in most countries. Internationally, it is regulated by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. In the United States, the manufacture, importation, possession, and distribution of cocaine is additionally regulated by the 1970 Controlled Substances Act. Cocaine is generally treated as a 'hard drug', with severe penalties for possession and trafficking. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Medicine=== | ||

| + | Coca leaf traditionally has been used for a variety of medical purposes, including as a stimulant to overcome fatigue, hunger, and thirst. It has been said to reduce hunger pangs and add enhance physical performance, adding strength and endurance for work (Boucher 1991; WebMD 2013b). Coca leaf also has been used to overcome altitude sickness, and in the Andes tourists have been offered coca tea for this purpose (Cortes 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In addition, coca extracts have been used as a muscle and cerebral stimulant to alleviate nausea, vomiting, and stomach pains without upsetting digestion (WebMD 2013b). Because coca constricts blood vessels, it also serves to oppose bleeding, and coca seeds were used for [[nosebleed]]s. Indigenous use of coca has also been reported as a treatment for [[malaria]], [[peptic ulcer|ulcer]]s, [[asthma]], to improve [[digestion]], to guard against bowel laxity, and as an [[aphrodisiac]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another purpose for coca and coca extracts has been as an [[anesthetic]] and analgesic to alleviate the pain of headache, [[rheumatism]], wounds, sores, and so forth. In Southeast Asia, the plant leaves have been chewed in order to get a plug of the leaf into a decayed tooth to alleviate toothache (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). Before stronger anesthetics were available, coca also was used for broken bones, childbirth, and during [[trephining]] operations on the skull. Today, cocaine has mostly been replaced as a medical anesthetic by synthetic analogues such as [[procaine]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the United States, cocaine remains an FDA-approved Schedule C-II drug, which can be prescribed by a healthcare provider, but is strictly regulated. A form of cocaine available by prescription is applied to the skin to numb eye, nose, and throat pain and narrow blood vessels (WebMD 2013b). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Nutrition and use as a chew and beverage=== | ||

| + | Raw coca leaves, chewed or consumed as tea or mate de coca, have a number of nutritional properties. Specifically, the coca plant contains essential minerals ([[calcium]], [[potassium]], [[phosphorus]]), [[vitamin]]s (B1, B2, C, and E) and nutrients such as [[protein]] and fiber (James et al. 1975). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Chewing of unadulterated coca leaves has been a tradition in the Andes for thousands of years and remains practiced by millions in South America today (Cortes 2013). Individuals may suck on wads of the leaves and keep them in their cheeks for hours at a time, often combining with chalk or ask to help dissolve the alkaloids into the saliva (Boucher 1991). While the cocaine in the plant has little effect on the unbroken skin, it does act on the mucous membranes of the mouth, as well as the membranes of the eye, nose, and stomach (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Coca leaves also can be boiled to provide a tea. Although coca leaf chewing is common mainly among the indigenous populations, the consumption of coca tea (''[[Mate de coca]]'') is common among all sectors of society in the Andean countries. Coca leaf is sold packaged into teabags in most grocery stores in the region, and establishments that cater to tourists generally feature coca tea. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the Andes commercially manufactured coca teas, granola bars, cookies, hard candies, etc. are available in most stores and supermarkets, including upscale suburban supermarkets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One beverage particularly tied to coca is Coca-Cola, a carbonated soft drink produced by the Coca-Cola Company. Production of Coca-Cola currently uses a coca extract with its cocaine removed as part of its "secret formula." Coca-Cola originally was introduced to the public in 1886 as a patent medicine. It is uncertain how much cocaine was in the original formulation, but it was stated that the founder, Pemberton, called for five ounces of coca leaf per gallon of syrup. However, by 1891, just five years later, the amount was significantly cut to only a trace amount—at least partly in response to concern about the negative aspects of cocaine. The ingredient was left in in order to protect the trade name of Coca-Cola (the Kola part comes from Kola nuts, which continue to serve for flavoring and the source of [[caffeine]]). By 1902, it was held that Coca-Cola contained a little as 1/400th of a grain of cocaine per ounce of syrup. In 1929, Coca-Cola became cocaine-free, but before then it was estimated that the amount of cocaine already was no more than one part in 50 million, such that is the entire year's supply (25-odd million gallons) of Coca-Cola syrup would yield but 6/100th of an ounce of cocaine (Mikkelson 2011; Liebowitz 1983; Cortes 2013). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Religion and culture=== | ||

| + | The coca plant has played an important role in religious, royal, and cultural occasions. Coca has been a vital part of the religious cosmology of the Andean peoples of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, northern Argentina, and Chile from the [[Pre-Inca cultures|pre-Inca period]] through the present. Coca has been called the "divine plant of the Incas" (Mortimer 1974) and coca leaves play a crucial part in offerings to the [[apus]] (mountains), [[Inti]] (the sun), or [[Pachamama]] (the earth). Coca leaves are also often read in a form of [[divination]] analogous to reading tea leaves in other cultures. In addition, coca use in shamanic rituals is well documented wherever local native populations have cultivated the plant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The coca plant also has been used in reciprocating manners in the Andrea culture, with cultural exchanges involving coca (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). The plant has been offered by a prospective son-in-law to his girl's father, relatives may chew on coca leaves to celebrate a birth, a woman may use coca to hasten and ease the pain of labor, and coca leaves may be put in one's coffin before burial (Leffel). | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Altman, A. J., D. M. Albert, and G. A. Fournier. 1985. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3885453 Cocaine's use in ophthalmology: Our 100-year heritage]. ''Surv Ophthalmol'' 29(4): 300–6. PMID 3885453. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | |

| − | * [http:// | + | * Boucher, D. H. 1991. Cocaine and the coca plant. ''BioScience'' 41(2): 72-76. |

| − | * [http:// | + | * Casale, J. F., and R. F. X. Klein. 1993. [http://www.erowid.org/archive/rhodium/chemistry/cocaine.illicit.production.html Illicit production of cocaine]. ''Forensic Science Review'' 5: 95-107. Retrieved June 3, 2019. |

| − | * [http:// | + | * Cortes, R. 2013. [http://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/condemned-coca-leaf-article-1.1238569 The condemned coca leaf]. ''NY Daily News'' January 13, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2019. |

| − | *[http:// | + | * de Medeiros, M. S. C., and A. Furtado Rahde. 1989. [http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/plant/erythrox.htm#SectionTitle:3.1%20Description%20of%20the%20plant ''Erythroxylum coca Lam'']. ''inchem.org''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. |

| + | * Dion, M. L., and C. Russler. 2008. [http://michelledion.com/files/2008-Dion%20and%20Russler-JLAS.pdf Eradication efforts, the state, displacement and poverty: Explaining coca cultivation In Colombia during Plan Colombia]. ''Journal of Latin American Studies'' 40: 399–421. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Drug Enforcement Agency. 1993. [http://www.erowid.org/archive/rhodium/chemistry/coca2cocaine.html Coca cultivation and cocaine processing: An overview]. ''EROWID''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Gaedcke, F. 1855. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ardp.18551320208/abstract;jsessionid=714476B632CFE3954D9571D4A9862AE7.d01t01 Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivirten Strauches ''Erythroxylon coca'' Lam]. ''Archiv der Pharmazie'' 132(2): 141-150. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Hurtado, J. 1995. ''Cocaine the Legend: About Coca and Cocaine'' La Paz, Bolivia: Accion Andina, ICORI. | ||

| + | * Inciardi,J. A. 1992. ''The War on Drugs II: The Continuing Epic of Heroin, Cocaine, Crack, Crime, AIDS, and Public Policy''. Mayfield. ISBN 1559340169. | ||

| + | * International Narcotics Control Board. 1994. [https://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR1994/E-INCB-1994-1-Supp-1-e.pdf Evaluation of the effectiveness of the international drug control treaties], Supplement to the INCB Annual Report for 1994 (Part 3). ''United Nations''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). 2007. [http://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR2007/AR_07_English.pdf Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2007]. ''United Nations''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * James, A., D. Aulick, and T. Plowman. 1975. ''Nutritional Value of Coca''. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 24(6): 113-119. | ||

| + | * Leffel, T. n.d. [http://www.transitionsabroad.com/publications/magazine/0605/the_coca_plant_paradox.shtml The coca plant paradox]. ''TransitionsAbroad''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Liebowitz, M. R. 1983. ''The Chemistry of Love''. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co. ISNB 0316524301. | ||

| + | * Marieb, E. N. and K. Hoehn. 2010. Human Anatomy & Physiology, 8th edition. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805395693. | ||

| + | * Mazza, G. 2013. [https://www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com/erythroxylum-novogranatense/ ''Erythroxylum novogranatense]. ''Photomazza.com''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Mikkelson, B. 2011. [http://www.snopes.com/cokelore/cocaine.asp Cocaine-Cola]. ''Snopes.com''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Mortimer, G. W. 1974. ''History of Coca: The Divine Plant of the Incas''. San Francisco: And Or Press. | ||

| + | * Musto, D. F. 1998. International traffic in coca through the early 20th century. ''Drug and Alcohol Dependence'' 49(2): 145–156. | ||

| + | * Nathanson, J. A., E. J. Hunnicutt, L. Kantham, and C. Scavone. 1993. [http://www.pnas.org/content/90/20/9645.full.pdf Cocaine as a naturally occurring insecticide]. ''Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci.'' 90: 9645-9648. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Niemann, A. 1860. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ardp.18601530202/abstract Ueber eine neue organische Base in den Cocablättern]. ''Archiv der Pharmazie'' 153(2): 129-256. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Office of Diversion Control (ODC). 2011. [https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2011/12/12/2011-31767/importer-of-controlled-substances-notice-of-registration Importers Notice of Registration - 2011]. ''Drug Enforcement Agency, U.S. Department of Justice''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Plowman T. 1984. The origin, evolution, and diffusion of coca, ''Erythroxylum spp.'', in South and Central America. Pages 125-163 in D. Stone, ''Pre-Columbian Plant Migration''. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Vol 76. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0873652029. | ||

| + | * Plowman, T, and L. Rivier. 1983. Cocaine and Cinnamoylcocaine content of thirty-one species of ''Erythroxylum'' (Erythroxylaceae)". ''Annals of Botany'' 51: 641–659. | ||

| + | * Rivera, M. A., A. C. Aufderheide, L. W. Cartmell, C. M. Torres, and O. Langsjoen. 2005. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16480174 Antiquity of coca-leaf chewing in the south central Andes: A 3,000 year archaeological record of coca-leaf chewing from northern Chile.] ''Journal of Psychoactive Drugs'' 37(4): 455–458. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 1985. [http://plants.jstor.org/upwta/2_42 Entry for ''Erythroxylum coca'' Lam. [family ERYTHROXYLACEAE]]. ''JSTOR''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Sulz, C. H. 1888. [http://chestofbooks.com/food/beverages/A-Treatise-On-Beverages/Coca-Plant.html#.UgBXU20phXF#ixzz2b9MIcIZW ''A Treatise On Beverages or The Complete Practical Bottler'']. Dick & Fitzgerald Publishers. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * Turner C. E., M. A. Elsohly, L. Hanuš L., and H. N. Elsohly. 1981. Isolation of dihydrocuscohygrine from Peruvian coca leaves. ''Phytochemistry'' 20(6): 1403-1405. | ||

| + | * United Nations (UN). 1961. [http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/treaties/single-convention.html Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs] ''United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | *United Nations Drug Control (UNDC). 2008. [http://www.undrugcontrol.info/en/issues/unscheduling-the-coca-leaf/item/1005-the-resolution-of-ambiguities-regarding-coca The resolution of ambiguities regarding coca]. ''United Nations''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (USODC). 2011. [http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Studies/Transatlantic_cocaine_market.pdf The transatlantic cocaine market: Research paper]. ''United Nations''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2013. [https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2013/January/bolivia-to-re-accede-to-un-drug-convention-while-making-exception-on-coca-leaf-chewing.html Bolivia to re-accede to UN drug convention, while making exception on coca leaf chewing]. ''United Nations''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * WebMD. 2013a. [https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/addiction/cocaine-use-and-its-effects#1 What Is Cocaine?]. ''WebMD''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| + | * WebMD. 2013b. [http://www.webmd.com/vitamins-supplements/ingredientmono-748-COCA.aspx?activeIngredientId=748&activeIngredientName=COCA Find a vitamin or supplement: Coca]. ''WebMD''. Retrieved June 3, 2019. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, H. (Ed.) 1911. ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 11th ed. Cambridge University Press. | |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Plants]] | [[Category:Plants]] | ||

| − | {{credit| | + | {{credit|Coca|566085453}} |

Latest revision as of 21:43, 4 June 2019

| Coca | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Coca is the common name for four domesticated varieties of tropical plants belonging to the two species Erythroxylum coca and E. novogranatense, whose leaves are used for a variety of purposes, including serving as the source of the drug cocaine. The four varieties are E. coca var. coca (Bolivian or Huánuco coca), E. coca var. ipadu (Amazonian coca), E. novogranatense var. novogranatense (Colombian coca), and E. novogranatense var. truxillense (Trujillo coca). The plant, which is native to the Andes Mountains and Amazon of South America, now also is grown in limited quantities in other regions with tropical climates.

Coca is particularly renowned worldwide for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine. While the alkaloid content of coca leaves is low, when the leaves are processed they can provide a concentrated source of cocaine. This purified form, which is used nasally, smoked, or injected, can be very addictive and have deleterious impacts on the brain, heart, respiratory system, kidneys, sexual system, and gastrointestinal tract. It can create a cycle where the user has difficulty experiencing pleasure without the drug.

For the plant, cocaine seems to serve a valuable function as an effective insecticide, limiting damage from herbivorous insects.

The coca leaves have been used unprocessed for thousands of years in South America for various religious, social, medicinal, and nutritional purposes, including to control hunger and combat the impacts of high altitudes. It has been called the "divine plant of the Incas." Unprocessed coca leaves are also commonly used in the Andean countries to make a herbal tea with mild stimulant effects. However, since the alkaloid cocaine is present in only trace amounts in the leaves, it does not cause the euphoric and psychoactive effects associated with use of the drug. Cocaine is available as a prescription for such purposes as external application to the skin to numb pain.

The Coca-Cola company uses a cocaine-free coca extract. In the early days of the manufacture of Coca-Cola beverage, the formulation did contain some cocaine, although within a few years of its introduction it already was only trace amounts.

Species and varieties

There are two species of cultivated coca, each with two varieties:

- Erythroxylum coca

- Erythroxylum coca var. coca (Bolivian or Huánuco coca) - well adapted to the eastern Andes of Peru and Bolivia, an area of humid, tropical, montane forest.

- Erythroxylum coca var. ipadu (Amazonian coca) - cultivated in the lowland Amazon Basin in Peru and Colombia.

- Erythroxylum novogranatense

- Erythroxylum novogranatense var. novogranatense (Colombian coca) - a highland variety that is utilized in lowland areas. It is cultivated in drier regions found in Colombia. However, E. novogranatense is very adaptable to varying ecological conditions.

- Erythroxylum novogranatense var. truxillense (Trujillo coca) - grown primarily in Peru and Colombia.

All four of the cultivated cocas were domesticated in pre-Columbian times and are more closely related to each other than to any other species (Plowman 1984). E. novogranatense was historically seen as a variety or subspecies of E. coca (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). The two subspecies of Erythroxylum coca are almost indistinguishable phenotypically. Erythroxylum novogranatense var. novogranatense and Erythroxylum novogranatense var. truxillense are phenotypically similar, but morphologically distinguishable.

Under the older Cronquist system of classifying flowering plants, coca was placed in an order Linales; more modern systems place it in the order Malpighiales.

Wild populations of Erythroxylum coca var. coca are found in the eastern Andes; the other 3 taxa are only known as cultivated plants.

Description

Coca plants tend to be evergreen shrubs with straight, reddish branches. This later quality is reflected in the name of the genus, Erythroxylum, which is a combination of the Greek erythros, meaning "red," and xylon, meaning "wood" (Mazza 2013). The coca plants tend to have oval to elliptical green leaves tapering at the ends, small yellowish-green flowers with heart-shaped anthers, and fruits in the form of red drupes with a single seed.

The coca plant is largely an understory species, found in moist tropical forests. It is native to the eastern Andes slopes and the Amazon. It does well at high elevations, being cultivated in Bolivia at elevations of 1000 to 2000 meters, but it also is cultivated at lower elevations, including lowland rainforests (Boucher 1991).

Erythroxylum coca

The wild E. coca commonly reaches a height of about 3 to 5.5 meters (12-18 ft), whereas the domestic plant is usually kept to about 2 meters (6 ft). The stem reaches about 16 centimeters in diameter and has a whitish bark. The branches are reddish, straight, and alternate. There is perennial renewal of the branches in a geometrical progression after being cut (de Medeiros and Rahde 1989).

The leaves of E. coca are green or greenish brown, smooth, opaque, and oval or elliptical, and generally about 1.5 to 3 centimeters (0.6-1.2 inches) wide and reach to 11 centimeters (4.3 inches) long. A special feature of the leaf is that the areolate portion is bordered by two curved, longitudinal lines, with one on either side of the midrib and more pronounced on the underside of the leaf. The small yellowish-green flowers give way to red berries, which are drupaceous and oblong, measuring about 1 centimeter (0.4 inches), and with only one seed (de Medeiros and Rahde 1989).

While both E. coca var. coca and E. coca var. ipadu have leaves that are broadly elliptical, the ipadu variety tends to have a more rounded apex versus the more pointed variety coca (DEA 1993).

Erythroxylum novogranatense

E. novogranatense grows to about 3 meters (10 feet), with leaves that are bright green, alternate, obovate or oblong-elliptic and on about a 0.5 centimeter (0.2 in) long petiole. The leaves are about 2 to 6 centimeters (0.8-2.4 in) long and 1 to 3 centimeters (0.4-1.2 in) broad. The flowers are hermaphrodite, solitary or grouped, axillary, and with five yellowish, white petals, about 0.4 centimeters (0.16 in) long and 0.2 centimeters (0.08 in) wide. The fruits are drupes, of oblong shape and red color, with only one oblong seed. They get to be about 0.8 centimeters (0.3 in) long and 0.3 centimeters (0.1 in) in diameter (Mazza 2013).

The leaf of E. novogranatense var. novogranatense tends to have a paler green color, more rounded apex, and be somewhat thinner and narrower than the leaf of E. coca (DEA 1993).

E. novogranatense var. truxillense is very similar to E. novogranatense var. novogranatense but differs in that the latter has longitudinal lines on either side of the central nervation (as with E. coca) while this is lacking in the truxillense variety (Mazza 2013).

The species name comes from novus, a, um, meaning "new," and granatensis, meaning "of Granada," from the name "Nueva Granada," the name that Colombia was called at the time of the Spanish conquest (Mazza 2013).

Cocaine and other alkaloids

The coca plant has many alkaloids, such as cocaine. Alkaloids are chemical compounds that are naturally occurring and contain mostly basic nitrogen atoms. Well-known alkaloids include caffeine found in the seed of the coffee plant and the leaves of the tea bush; nicotine found in the nightshade family of plants including the tobacco plant (Nicotiana tabacum); morphine found in poppies; and theobromine found in the cacao plant. Other well-known alkaloids include mescaline, strychnine, quinine, and codeine.

Among the about 14 diverse alkaloids identified in the coca plant are ecgonine, hygrine, truxilline, benzoylecgonine, and tropacocaine. Coca leaves have been reported as having 0.5 to 1.5% alkaloids by dry weight (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985).

The most concentrated alkaloid is cocaine (cocaine (methyl benzoyl ecgonine or benzoylmethylecgonine). Concentrations vary by variety and region, but leaves have been reported variously as between 0.25% and 0.77% (Plowman and Rivier 1983), between 0.35% and 0.72% by dry weight (Nathanson et al. 1993), and between 0.3% and 1.5% and averaging 0.8% in fresh leaves (Casale and Klein 1993). E. coca var. ipadu is not as concentrated in cocaine alkaloids as the other three varieties (DEA 1993). Boucher (1991) reports that the coca leaves from Bolivia, while considered to be of higher quality by traditional users, have lower concentrations of cocaine than leaves from the Chapare Valley. He also reports those leaves with smaller amounts of cocaine have traditionally been preferred for chewing, being associated with a sweet or less bitter taste, while those preferred for the drug trade prefer those leaves with a greater alkaloid content.

For the plant, cocaine is believed to serve as a naturally occurring insecticide, with the alkaloid exerting such effects at concentrations normally found in the leaves (Nathanson et. al. 1993). It has been observed that compared to other tropical plants, coca seems to be relatively pest free, with little observed damage to the leaves and rare observations of herbivorous insects on plants in the field (Nathanson et al. 1993).

Cultivation

Ninety-eight percent of the global land area plant with coca is in the three nations of Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia (Dion and Russler 2008). However, while it is, or has been grown, in other nations, including Taiwan, Indonesia, Formosa, India, Java, Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Cameroon, coca cultivation has largely been abandoned outside South America since the mid 1900s (Boucher, 1991; Royal Botanic Gardens 2013). The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimated, in a 2011 report, that in 2008 Colombia was responsible for about half of global production of coca, while Peru contributed over one-third, and Bolivia the rest, although coca leaf production in Colombia has been declining over the past ten years while that of Peru has been increasing and by 2009 they may have reach similar output levels (UNODC 2011).

E. coca var. coca (Bolivian or Huánuco coca) is the most widely grown variety and is cultivated is the eastern slopes of the Andes, from Bolivia in the south through Peru to Ecuador in the north. It tends mostly to be cultivated in Bolivia and Peru, and largely between 500 meters to 1500 meters (1,650-4,950 feet). E. coca var. ipadu (Amazonian coca) is found in the Amazon basin, in southern Colombia, northeastern Peru, and western Brazil. It tends mostly to be cultivated in Peru and Colombia. E. novogranatense var. novogranatense (Colombian coca) thrives in Colombia and is grown to some extent in Venezuela. E. novogranatense var. truxillense (Trujillo coca) is largely cultivated in Peru and Colombia; this variety is grown to 1500 meters (DEA 1993).

While locations that are hot, damp, and humid are particularly conducive to growth of coca plants, the leaves with the highest concentrations of cocaine tend to be found among those grown at higher, cooler, and somewhat drier altitudes.

Coca plants are grown from seeds that are collected from the drupes when ripe. The seeds are allowed to dry and then placed in seed beds, typically sheltered from the sun, and germinate in about 3 weeks. The plants are transplanted to prepared fields when they reach about 30 to 60 centimeters in height, which is about 2 months of age. Plants can be harvested 12 to 24 months after being transplanted (Casale and Klein 1993; DEA 1993).

Although the plants grow to more than 3 meters, the cultivated coca plants are typically pruned to 1 to 2 meters to ease harvest. Likewise, although the plants can live up to 50 years, they often are uprooted or cut back to near ground level after 5 to 10 years because of concern about decreasing cocaine content in the older shrubs (Casale and Klein 1993; DEA 1993).

Leaves are harvested year round. Harvesting is mainly of new fresh growth. The leaves are dried in the sun and then packed for distribution; leaves are kept dry in order to preserve the leaf quality.

History

There is archeological evidence that suggests the use of coca leaves 8000 years ago, with the finding of coca leaves of that date (6000 B.C.E.) in floors in Peru, along with pieces of calcite (calcium carbonate), which is used by those chewing leaves to bring out the alkaloids by helping dissolve them into the saliva (Boucher 1991). Coca leaves also have been found in the Huaca Prieta settlement in northern Peru, dated from about 2500 to 1800 B.C.E. (Hurtado 1995). Traces of cocaine also have been in 3000-year-old mummies of the Alto Ramirez culture of Northern Chile, suggesting coca-leaf chewing dates to at least 1500 B.C.E. (Rivera et al. 2005). The remains of coca leaves not only have been found with ancient Peruvian mummies, but pottery from the time period depicts humans with bulged cheeks, indicating the presence of something on which they are chewing (Altman et al. 1985). It is the view of Boucher (1991) that the coca plant was domesticated by 1500 B.C.E.

In the pre-Columbian era, coca was a main part of the economic system and was exchanged for fruits and furs from the Amazon, potatoes and grains from the Andean highlands, and fish and shells from the Pacific (Boucher 1991). The use of coca for currency continued during the Colonial Period because it was considered even more valuable than silver or gold. Uses of coca in the early times include use for curing aliments, providing energy, making religious offerings, and forecasting of events (Hurtado 2010).

Coca chewing may originally have been limited to the eastern Andes before its introduction to the Incas. As the plant was viewed as having a divine origin, its cultivation became subject to a state monopoly and its use restricted to nobles and a few favored classes (court orators, couriers, favored public workers, and the army) by the rule of the Topa Inca (1471–1493). As the Incan empire declined, the leaf became more widely available. After some deliberation, Philip II of Spain issued a decree recognizing the drug as essential to the well-being of the Andean Indians but urging missionaries to end its religious use. The Spanish are believed to have effectively encouraged use of coca by an increasing majority of the population to increase their labor output and tolerance for starvation, but it is not clear that this was planned deliberately.

Coca was first introduced to Europe in the sixteenth century. However, coca did not become popular until the mid-nineteenth century, with the publication of an influential paper by Dr. Paolo Mantegazza praising its stimulating effects on cognition. This led to invention of coca wine and the first production of pure cocaine.

The cocaine alkaloid was first isolated by the German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855. Gaedcke named the alkaloid "erythroxyline", and published a description in the journal Archiv der Pharmazie (Gaedcke 1855). Cocaine also was isolated in 1859 by Albert Niemann of the University of Göttingen, using an improved purification process (Niemann 1860). It was Niemann who named coca's chief alkaloid "cocaine" (Inciardi 1992).

Coca wine (of which Vin Mariani was the best-known brand) and other coca-containing preparations were widely sold as patent medicines and tonics, with claims of a wide variety of health benefits. The original version of Coca-Cola was among these, although the amount in Coca-Cola may have been only trace amounts. Products with cocaine became illegal in most countries outside of South America in the early twentieth century, after the addictive nature of cocaine was widely recognized.

In the early twentieth century, the Dutch colony of Java became a leading exporter of coca leaf. By 1912, shipments to Amsterdam, where the leaves were processed into cocaine, reached 1 million kg, overtaking the Peruvian export market. Apart from the years of the First World War, Java remained a greater exporter of coca than Peru until the end of the 1920s (Musto 1998). As noted above, since the mid-1900s, coca cultivation outside South America has virtually been abandoned.

International prohibition of coca leaf

As the raw material for the manufacture of the recreational drug cocaine, the coca leaf has been the target of international efforts to restrict its cultivation in an attempt to prevent the production of cocaine. While the cultivation, sale, and possession of unprocessed coca leaf (but not of any processed form of cocaine) is generally legal in the countries where traditional use is established—such as Bolivia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina—cultivation even in these countries is often restricted. In the case of Argentina, it is legal only in some northern provinces where the practice is so common that the state has accepted it.

The prohibition of the use of the coca leaf except for medical or scientific purposes was established by the United Nations in the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. The coca leaf is listed on Schedule I of the 1961 Single Convention together with cocaine and heroin. The Convention determined that "The Parties shall so far as possible enforce the uprooting of all coca bushes which grow wild. They shall destroy the coca bushes if illegally cultivated" (Article 26), and that "coca leaf chewing must be abolished within twenty-five years from the coming into force of this Convention" (Article 49, 2.e). The Convention recognized as an acceptable use of the coca leaves for preparing a flavoring agent without the alkaloids, and import, export, trade, and possession of the leaves for such purpose. However, the Convention also noted that whenever prevailing conditions render prohibition of cultivation the most suitable measure for preventing diversion of the crop into the illicit drug trade and for protection of health and general welfare, then the nation "shall prohibit cultivation" (UN 1961).

Despite the legal restriction among countries party to the international treaty, coca chewing and drinking of coca tea is carried out daily by millions of people in the Andes as well as considered sacred within indigenous cultures. In recent times, the governments of several South American countries, such as Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela, have defended and championed the traditional use of coca, as well as the modern uses of the leaf and its extracts in household products such as teas and toothpaste.

In an attempt to obtain international acceptance for the legal recognition of traditional use of coca in their respective countries, Peru and Bolivia successfully led an amendment, paragraph 2 of Article 14 into the 1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, stipulating that measures to eradicate illicit cultivation and to eliminate illicit demand "should take due account of traditional licit use, where there is historic evidence of such use" (UNDC 2008).

Bolivia also made a formal reservation to the 1988 Convention. This convention required countries to adopt measures to establish the use, consumption, possession, purchase or cultivation of the coca leaf for personal consumption as a criminal offense. Bolivia stated that "the coca leaf is not, in and of itself, a narcotic drug or psychotropic substance" and stressed that its "legal system recognizes the ancestral nature of the licit use of the coca leaf, which, for much of Bolivia's population, dates back over centuries" (UNDC 2008).

However, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB)—the independent and quasi-judicial control organ for the implementation of the United Nations drug conventions—denied the validity of article 14 in the 1988 Convention over the requirements of the 1961 Convention, or any reservation made by parties, since it does not "absolve a party of its rights and obligations under the other international drug control treaties" (UNDC 2008; INCB 2007). The INCB considered Bolivia, Peru, and a few other countries that allow such practices as coca-chewing and drinking of coca tea to be in breach with their treaty obligations, and insisted that "each party to the Convention should establish as a criminal offence, when committed intentionally, the possession and purchase of coca leaf for personal consumption" (INCB 2007). The INCB noted in its 1994 Annual Report that "mate de coca, which is considered harmless and legal in several countries in South America, is an illegal activity under the provisions of both the 1961 Convention and the 1988 Convention, though that was not the intention of the plenipotentiary conferences that adopted those conventions." The INCB also implicitly dismissed the original report of the Commission of Enquiry on the Coca Leaf by recognizing that "there is a need to undertake a scientific review to assess the coca-chewing habit and the drinking of coca tea."(INCB 1994).

In reaction to the 2007 Annual Report of the INCB, the Bolivian government announced that it would formally issue a request to the United Nations to unschedule the coca leaf of List 1 of the 1961 UN Single Convention. Bolivia led a diplomatic effort to do so beginning in March 2009. In that month, the Bolivian President, Evo Morales, went before the United Nations and relayed the history of coa use for such purposes as medicinal, nutritional, social, and spiritual, and he at that time put a leaf in his mouth (Cortes 2013). However, Bolivia's effort to have the coca leaf removed from the List 1 of the 1960 UN Single Convention was unsuccessful, when eighteen countries objected to the change before the January 2011 deadline. A single objection would have been sufficient to block the modification. The legally unnecessary step of supporting the change was taken formally by Spain, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Costa Rica.

In June 2011, Bolivia moved to denounce the 1961 Convention over the prohibition of the coca leaf.

On January 1, 2012 Bolivia's withdrawal from the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs came into effect. However, Bolivia took steps to again become a party to the 1961 Single Convention conditional on the acceptance of a reservation on the chewing of coca leaf. For this reservation not to pass, one-third of the 183 States party to this convention would have had to object within one year after the proposed reservation was submitted. This deadline expired on January 10, 2013, with only 15 countries objecting to Bolivia's reservation, thus permitting the reservation, and Bolivia's re-accession to the Convention came into force on January 10, 2013 (UNODC 2013).

Currently, outside of South America, most countries' laws make no distinction between the coca leaf and any other substance containing cocaine, so the possession of coca leaf is prohibited. In South America, coca leaf is illegal in both Paraguay and Brazil.

In the Netherlands, coca leaf is legally in the same category as cocaine, both are List I drugs of the Opium Law. The Opium Law specifically mentions the leafs of the plants of the genus Erythroxylon. However, the possession of living plants of the genus Erythroxylon are not actively prosecuted, even though they are legally forbidden.

In the United States, a Stepan Company plant in Maywood, New Jersey is a registered importer of coca leaf. The company manufactures pure cocaine for medical use and also produces a cocaine-free extract of the coca leaf, which is used as a flavoring ingredient in Coca-Cola. Other companies have registrations with the DEA to import coca leaf according to 2011 Federal Register Notices for Importers (ODC 2011), including Johnson Matthey, Inc, Pharmaceutical Materials; Mallinckrodt Inc; Penick Corporation; and the Research Triangle Institute.

Uses

Recreational psychoactive drug

Coca leaf is the raw material for the manufacture of the psychoactive drug cocaine, a powerful stimulant extracted chemically from large quantities of coca leaves. Cocaine is best known worldwide for such illegal use. This concentrated form of cocaine is used nasally (nasal insufflation is also known as "snorting," "sniffing," or "blowing" and involves absorption through the mucous membranes lining the sinuses), injected (the method that produces the highest blood levels in the shortest time), or smoked (notably the cheaper, more potent form called "crack").

Use of concentrated cocaine yields pleasure through its interference with neurotransmitters, blocking the neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, from being reabsorbed, and thus resulting in continual stimulation. However, such drug use can have deleterious impacts on the brain, heart, respiratory system, kidneys, sexual system, and gastrointestinal tract (WebMD 2013a). For example, it can result in a heart attack or strokes, even in young people,and it can cause ulcers and sudden kidney failure, and it can impair sexual function (WebMD 2013a). It also can be highly addictive, creating intense cravings for the drug, and result in the cocaine user becoming "in a very real sense, unable to experience pleasure without the drug" (Marieb and Hoehn 2010).

The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime estimated that in 2009, the US cocaine market was $37 billion (and shrinking over the past ten years) and the West and Central European Cocaine market was US$ 33 billion (and increasing over the past ten years) (USODC 2011).

The production, distribution and sale of cocaine products is restricted and/or illegal in most countries. Internationally, it is regulated by the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. In the United States, the manufacture, importation, possession, and distribution of cocaine is additionally regulated by the 1970 Controlled Substances Act. Cocaine is generally treated as a 'hard drug', with severe penalties for possession and trafficking.

Medicine

Coca leaf traditionally has been used for a variety of medical purposes, including as a stimulant to overcome fatigue, hunger, and thirst. It has been said to reduce hunger pangs and add enhance physical performance, adding strength and endurance for work (Boucher 1991; WebMD 2013b). Coca leaf also has been used to overcome altitude sickness, and in the Andes tourists have been offered coca tea for this purpose (Cortes 2013).

In addition, coca extracts have been used as a muscle and cerebral stimulant to alleviate nausea, vomiting, and stomach pains without upsetting digestion (WebMD 2013b). Because coca constricts blood vessels, it also serves to oppose bleeding, and coca seeds were used for nosebleeds. Indigenous use of coca has also been reported as a treatment for malaria, ulcers, asthma, to improve digestion, to guard against bowel laxity, and as an aphrodisiac.

Another purpose for coca and coca extracts has been as an anesthetic and analgesic to alleviate the pain of headache, rheumatism, wounds, sores, and so forth. In Southeast Asia, the plant leaves have been chewed in order to get a plug of the leaf into a decayed tooth to alleviate toothache (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). Before stronger anesthetics were available, coca also was used for broken bones, childbirth, and during trephining operations on the skull. Today, cocaine has mostly been replaced as a medical anesthetic by synthetic analogues such as procaine.

In the United States, cocaine remains an FDA-approved Schedule C-II drug, which can be prescribed by a healthcare provider, but is strictly regulated. A form of cocaine available by prescription is applied to the skin to numb eye, nose, and throat pain and narrow blood vessels (WebMD 2013b).

Nutrition and use as a chew and beverage

Raw coca leaves, chewed or consumed as tea or mate de coca, have a number of nutritional properties. Specifically, the coca plant contains essential minerals (calcium, potassium, phosphorus), vitamins (B1, B2, C, and E) and nutrients such as protein and fiber (James et al. 1975).

Chewing of unadulterated coca leaves has been a tradition in the Andes for thousands of years and remains practiced by millions in South America today (Cortes 2013). Individuals may suck on wads of the leaves and keep them in their cheeks for hours at a time, often combining with chalk or ask to help dissolve the alkaloids into the saliva (Boucher 1991). While the cocaine in the plant has little effect on the unbroken skin, it does act on the mucous membranes of the mouth, as well as the membranes of the eye, nose, and stomach (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985).

Coca leaves also can be boiled to provide a tea. Although coca leaf chewing is common mainly among the indigenous populations, the consumption of coca tea (Mate de coca) is common among all sectors of society in the Andean countries. Coca leaf is sold packaged into teabags in most grocery stores in the region, and establishments that cater to tourists generally feature coca tea.

In the Andes commercially manufactured coca teas, granola bars, cookies, hard candies, etc. are available in most stores and supermarkets, including upscale suburban supermarkets.

One beverage particularly tied to coca is Coca-Cola, a carbonated soft drink produced by the Coca-Cola Company. Production of Coca-Cola currently uses a coca extract with its cocaine removed as part of its "secret formula." Coca-Cola originally was introduced to the public in 1886 as a patent medicine. It is uncertain how much cocaine was in the original formulation, but it was stated that the founder, Pemberton, called for five ounces of coca leaf per gallon of syrup. However, by 1891, just five years later, the amount was significantly cut to only a trace amount—at least partly in response to concern about the negative aspects of cocaine. The ingredient was left in in order to protect the trade name of Coca-Cola (the Kola part comes from Kola nuts, which continue to serve for flavoring and the source of caffeine). By 1902, it was held that Coca-Cola contained a little as 1/400th of a grain of cocaine per ounce of syrup. In 1929, Coca-Cola became cocaine-free, but before then it was estimated that the amount of cocaine already was no more than one part in 50 million, such that is the entire year's supply (25-odd million gallons) of Coca-Cola syrup would yield but 6/100th of an ounce of cocaine (Mikkelson 2011; Liebowitz 1983; Cortes 2013).

Religion and culture

The coca plant has played an important role in religious, royal, and cultural occasions. Coca has been a vital part of the religious cosmology of the Andean peoples of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, northern Argentina, and Chile from the pre-Inca period through the present. Coca has been called the "divine plant of the Incas" (Mortimer 1974) and coca leaves play a crucial part in offerings to the apus (mountains), Inti (the sun), or Pachamama (the earth). Coca leaves are also often read in a form of divination analogous to reading tea leaves in other cultures. In addition, coca use in shamanic rituals is well documented wherever local native populations have cultivated the plant.

The coca plant also has been used in reciprocating manners in the Andrea culture, with cultural exchanges involving coca (Royal Botanic Gardens 1985). The plant has been offered by a prospective son-in-law to his girl's father, relatives may chew on coca leaves to celebrate a birth, a woman may use coca to hasten and ease the pain of labor, and coca leaves may be put in one's coffin before burial (Leffel).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Altman, A. J., D. M. Albert, and G. A. Fournier. 1985. Cocaine's use in ophthalmology: Our 100-year heritage. Surv Ophthalmol 29(4): 300–6. PMID 3885453. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Boucher, D. H. 1991. Cocaine and the coca plant. BioScience 41(2): 72-76.

- Casale, J. F., and R. F. X. Klein. 1993. Illicit production of cocaine. Forensic Science Review 5: 95-107. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Cortes, R. 2013. The condemned coca leaf. NY Daily News January 13, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- de Medeiros, M. S. C., and A. Furtado Rahde. 1989. Erythroxylum coca Lam. inchem.org. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Dion, M. L., and C. Russler. 2008. Eradication efforts, the state, displacement and poverty: Explaining coca cultivation In Colombia during Plan Colombia. Journal of Latin American Studies 40: 399–421. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Drug Enforcement Agency. 1993. Coca cultivation and cocaine processing: An overview. EROWID. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Gaedcke, F. 1855. Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivirten Strauches Erythroxylon coca Lam. Archiv der Pharmazie 132(2): 141-150. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Hurtado, J. 1995. Cocaine the Legend: About Coca and Cocaine La Paz, Bolivia: Accion Andina, ICORI.

- Inciardi,J. A. 1992. The War on Drugs II: The Continuing Epic of Heroin, Cocaine, Crack, Crime, AIDS, and Public Policy. Mayfield. ISBN 1559340169.

- International Narcotics Control Board. 1994. Evaluation of the effectiveness of the international drug control treaties, Supplement to the INCB Annual Report for 1994 (Part 3). United Nations. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). 2007. Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2007. United Nations. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- James, A., D. Aulick, and T. Plowman. 1975. Nutritional Value of Coca. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 24(6): 113-119.

- Leffel, T. n.d. The coca plant paradox. TransitionsAbroad. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Liebowitz, M. R. 1983. The Chemistry of Love. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co. ISNB 0316524301.

- Marieb, E. N. and K. Hoehn. 2010. Human Anatomy & Physiology, 8th edition. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 9780805395693.

- Mazza, G. 2013. Erythroxylum novogranatense. Photomazza.com. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Mikkelson, B. 2011. Cocaine-Cola. Snopes.com. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- Mortimer, G. W. 1974. History of Coca: The Divine Plant of the Incas. San Francisco: And Or Press.