Difference between revisions of "Child sacrifice" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 152: | Line 152: | ||

===Inca culture=== | ===Inca culture=== | ||

The [[Inca]] culture sacrificed children in a ritual called ''[[qhapaq hucha]]''. Their frozen corpses have been discovered in the [[South America]]n mountaintops. The first of these corpses, a female child who had died from a blow to the skull, was discovered in 1995 by Johan Reinhard.<ref>http://gallery.sjsu.edu/sacrifice/precolumbian.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060519021943/http://gallery.sjsu.edu/sacrifice/precolumbian.html |date=19 May 2006 }} - "Pre-Columbian Andean Sacrifices"</ref> Other methods of sacrifice included [[strangulation]] and simply leaving the children, who had been given an intoxicating drink, to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and low-oxygen conditions of the mountaintop, and to die of [[hypothermia]]. | The [[Inca]] culture sacrificed children in a ritual called ''[[qhapaq hucha]]''. Their frozen corpses have been discovered in the [[South America]]n mountaintops. The first of these corpses, a female child who had died from a blow to the skull, was discovered in 1995 by Johan Reinhard.<ref>http://gallery.sjsu.edu/sacrifice/precolumbian.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060519021943/http://gallery.sjsu.edu/sacrifice/precolumbian.html |date=19 May 2006 }} - "Pre-Columbian Andean Sacrifices"</ref> Other methods of sacrifice included [[strangulation]] and simply leaving the children, who had been given an intoxicating drink, to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and low-oxygen conditions of the mountaintop, and to die of [[hypothermia]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Moche culture=== | ===Moche culture=== | ||

Revision as of 15:20, 10 August 2022

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human sacrifice.

Child sacrifice is thought to be an extreme extension of the idea that, the more important the object of sacrifice, the more devout the person giving it up is.[1]

The practice of child sacrifice in Europe and the Near East appears to have ended as a part of the religious transformations of late antiquity.[2]

Pre-Columbian cultures

The practice of human sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures, in particular Mesoamerican and South American cultures, is well documented both in the archaeological records and in written sources. The exact ideologies behind child sacrifice in different pre-Columbian cultures are unknown but it is often thought to have been performed to placate certain gods.

Mesoamerica

Olmec culture

Although there is no incontrovertible evidence of child sacrifice in the Olmec civilization, full skeletons of newborn or unborn infants, as well as dismembered femurs and skulls, have been found at the El Manatí sacrificial bog. These bones are associated with sacrificial offerings, particularly wooden busts. It is not known yet how the infants met their deaths.[3]

Some researchers have also associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp "were-jaguar" babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (to the right) or Las Limas figure. Definitive answers await further findings.

Maya culture

In 2005 a mass grave of one- to two-year-old sacrificed children was found in the Maya region of Comalcalco. The sacrifices were apparently performed for consecration purposes when building temples at the Comalcalco acropolis.[4]

There are also skulls suggestive of child sacrifice dating to the Maya periods. Mayanists believe that, like the Aztecs, the Maya performed child sacrifice in specific circumstances. For example, infant sacrifice would occur to satisfy supernatural beings who would have eaten the souls of more powerful people.[5] In the Classic period some Maya art that depict the extraction of children's hearts during the ascension to the throne of the new kings, or at the beginnings of the Maya calendar have been studied.[6] In one of these cases, Stela 11 in Piedras Negras, Guatemala, a sacrificed boy can be seen. Other scenes of sacrificed boys are visible on painted jars.

Teotihuacan culture

There is evidence of child sacrifice in Teotihuacano culture. As early as 1906, Leopoldo Batres uncovered burials of children at the four corners of the Pyramid of the Sun. Archaeologists have found newborn skeletons associated with altars, leading some to suspect "deliberate death by infant sacrifice".[7]

Toltec culture

In 2007, archaeologists announced that they had analyzed the remains of 24 children, aged 5 to 15, found buried together with a figurine of Tlaloc. The children, found near the ancient ruins of the Toltec capital of Tula, had been decapitated. The remains have been dated to AD 950 to 1150.

"To try and explain why there are 24 bodies grouped in the same place, well, the only way is to think that there was a human sacrifice", archaeologist Luis Gamboa said.[8]

Aztec culture

Archeologists have found remains of 42 children. It is alleged that these remains were sacrificed to Tlaloc (and a few to Ehécatl, Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopochtli) in the offerings of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan by the Aztecs of pre-Columbian Mexico. In every case, the 42 children, mostly males aged around six, were suffering from serious cavities, abscesses or bone infections that would have been painful enough to make them cry continually. Tlaloc required the tears of the young so their tears would wet the earth. As a result, if children did not cry, the priests would sometimes tear off the children's nails before the ritual sacrifice.[9]

Human sacrifice was an everyday activity in Tenochtitlan and women and children were not exempt.[10][11]Template:Full citation needed[12][13] According to Bernardino de Sahagún, the Aztecs believed that, if sacrifices were not given to Tlaloc, the rain would not come and their crops would not grow.

The Aztec religion is one of the most widely documented pre-Hispanic cultures. Diego Durán in the Book of the Gods and Rites wrote about the religious practices devoted to the water gods, Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, and a very important part of their annual ritual included the sacrifice of infants and young children.

According to Bernardino de Sahagún, the Aztecs believed that, if sacrifices were not given to Tlaloc, the rain would not come and their crops would not grow. Archaeologists have found the remains of 42 children sacrificed to Tlaloc (and a few to Ehecátl Quetzalcóatl) in the offerings of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan. In every case, the 42 children, mostly males aged around six, were suffering from serious cavities, abscesses or bone infections that would have been painful enough to make them cry continually. Tlaloc required the tears of the young so their tears would wet the earth. As a result, if children did not cry, the priests would sometimes tear off the children's nails before the ritual sacrifice.[14]

Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, an Aztec descendant and the author of the Codex Ixtlilxochitl, claimed that one in five children of the Mexica subjects was killed annually. These high figures have not been confirmed by historians. Hernán Cortés describes an event in his Letters:

And they would take their children to kill and sacrifice to their Idols.

In Xochimilco, the remains of a three-to-four-year-old boy were found. The skull was broken and the bones had an orange/yellowish cast, a vitreous texture, and porous and compacted tissue. Aztecs have been known to boil down remains of some sacrificed victims to remove the flesh and place the skull in the tzompantli. Archaeologists concluded that the skull was boiled and that it cracked due to the ebullition of the brain mass. Photographs of the skull have been published in specialized journals.[15]

In History of the Things of New Spain Sahagún confesses he was aghast by the fact that, during the first month of the year, the child sacrifices were approved by their own parents, who also ate their children.[16]

In the month Atlacacauallo of the Aztec calendar (from February 2 to February 21 of the Gregorian Calendar) children and captives were sacrificed to the water deities, Tláloc, Chalchitlicue, and Ehécatl.

In the month Tozoztontli (from March 14 to April 2) children were sacrificed to Coatlicue, Tlaloc, Chalchitlicue, Tona.

In the month Hueytozoztli (from April 3 to April 22) a maid, a boy and a girl were sacrificed to Cintéotl, Chicomecacóatl, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl.

In the month Tepeilhuitl (from September 30 to October 19) children and two noble women were sacrificed by extraction of the heart and flaying; ritual cannibalism in honor of Tláloc-Napatecuhtli, Matlalcueye, Xochitécatl, Mayáhuel, Milnáhuatl, Napatecuhtli, Chicomecóatl, Xochiquétzal.

In the month Atemoztli (from November 29 to December 18) children and slaves were sacrificed by decapitation in honor of the Tlaloques.

South America

Archaeologists have uncovered physical evidence of child sacrifice at several pre-Columbian cultures in South America. In an early example, the Moche of Northern Peru sacrificed teenagers en masse, as archaeologist Steve Bourget found when he uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in 1995.[17] [18]

Chimú culture

The Chimú who occupied northern Peru before the Incas, and who were ultimately conquered by the Incas a few decades before the Spanish arrival, carried out what has been claimed as the largest single example of mass child sacrifice at Huanchaco, where their chief city of Chan Chan was located. Researchers have identified at least 227 individuals as sacrificial victims, and it is believed that this mass sacrifice may have been carried out to appease deities who were supposedly bringing extreme rainfall weather conditions upon the Chimú. [19] Archaeologists have found the remains of more than 140 children who were sacrificed in Peru's northern coastal region.[20]

Inca culture

Qhapaq hucha was the Inca practice of human sacrifice, mainly using children. The Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca (emperor) or during a famine. Children were selected as sacrificial victims as they were considered to be the purest of beings. These children were also physically perfect and healthy, because they were the best the people could present to their gods. The victims may be as young as 6 and as old as 15.

Months or even years before the sacrifice pilgrimage, the children were fattened up. Their diets were those of the elite, consisting of maize and animal proteins. They were dressed in fine clothing and jewelry and escorted to Cusco to meet the emperor where a feast was held in their honor. More than 100 precious ornaments were found to be buried with these children in the burial site.

The Incan high priests took the children to high mountaintops for sacrifice. As the journey was extremely long and arduous, especially so for the younger, coca leaves were fed to them to aid them in their breathing so as to allow them to reach the burial site alive. Upon reaching the burial site, the children were given an intoxicating drink to minimize pain, fear, and resistance. They were then killed either by strangulation, a blow to the head, or by leaving them to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and die of exposure.[21]

Early colonial Spanish missionaries wrote about this practice but only recently have archaeologists such as Johan Reinhard begun to find the bodies of these victims on Andean mountaintops, naturally mummified due to the freezing temperatures and dry windy mountain air.

Inca mummies

In 1995, the body of an almost entirely frozen young Inca girl (age 15), later named Mummy Juanita, was discovered on Mount Ampato. Two more ice-preserved mummies, one girl (age 6) and one boy (age 8), were discovered nearby a short while later. All showed signs of alcohol and coca leaves in their system, making them fall asleep, only to be frozen to death. The boy was the only one who showed signs of resistance, due to his hands and feet being tied up. It is also speculated that he might have died from suffocation, as vomit and blood were found on his clothing.

In 1999, near Llullaillaco's 6739 meter summit, an Argentine-Peruvian expedition found the perfectly preserved bodies of three Inca children, sacrificed approximately 500 years earlier,[22] including a 15-year-old girl, nicknamed "La doncella" (the maiden), a seven-year-old boy, and a six-year-old girl, nicknamed "La niña del rayo" (the lightning girl). The latter's nickname reflects the fact that sometime during the 500 years on the summit, the preserved body was struck by lightning, partially burning it and some of the ceremonial artifacts. The three mummies are exhibited in rotating fashion at the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology, specially built for them in Salta, Argentina.[23]

Scientific investigation suggests some child victims were drugged with ethanol and coca leaves during the time before their deaths.[24]

Timoto-Cuicas culture

The Timoto-Cuicas worshiped idols of stone and clay, built temples, and offered human sacrifices. Until colonial times, children were sacrificed secretly in Laguna de Urao, Mérida. This was chronicled by Juan de Castellanos, who described the feasts and human sacrifices that were done in honour of Icaque, an Andean prehispanic goddess.[25][26]

Inca culture

The Inca culture sacrificed children in a ritual called qhapaq hucha. Their frozen corpses have been discovered in the South American mountaintops. The first of these corpses, a female child who had died from a blow to the skull, was discovered in 1995 by Johan Reinhard.[27] Other methods of sacrifice included strangulation and simply leaving the children, who had been given an intoxicating drink, to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and low-oxygen conditions of the mountaintop, and to die of hypothermia.

Moche culture

The Moche of northern Peru practiced mass sacrifices of men and boys.[28] Archeologist found the remains of 137 children 3 adults along with 200 camelids between the excavation in 2014 to 2016, beneath the sands of a 15th-century site called Huanchaquito-Las Llamas. This sacrifice was possible made during the heavy rains as there was a layer of mud on top of the clean sand.[29][30][31][32]

Timoto-Cuica culture

The Timoto-Cuicas offered human sacrifices. Until colonial times children sacrifice persisted secretly in Laguna de Urao (Mérida). It was described by the chronicler Juan de Castellanos, who cited that feasts and human sacrifices were done in honour of Icaque, an Andean prehispanic goddess.[33][34]

Ancient Near East

Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

The Tanakh mentions human sacrifice in the history of ancient Near Eastern practice. The king of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (olah, as used of the Temple sacrifice). In the book of the prophet Micah, the question is asked, 'Shall I give my firstborn for my sin, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?',[35] and responded to in the phrase, 'He has shown all you people what is good. And what does Yahweh require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.'[36] The Tanakh also implies that the Ammonites offered child sacrifices to Moloch.[37]

Binding of Isaac

Genesis 21 relates the binding of Isaac, by Abraham to present his son, Isaac, as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah. It was a test of faith (Genesis 21:12). Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. Francesca Stavrakopoulou has speculated that it is possible that the story "contains traces of a tradition in which Abraham does sacrifice Isaac". Rabbi A.I. Kook, first Chief Rabbi of Israel, stressed that the climax of the story, commanding Abraham not to sacrifice Isaac, is the whole point: to put an end to the ritual of child sacrifice, which contradicts the morality of a perfect and giving (not taking) monotheistic God.[38] According to Irving Greenberg the story of the binding of Isaac, symbolizes the prohibition to worship God by human sacrifices, at a time when human sacrifices were the norm worldwide.[39]

Ban in Leviticus

In Leviticus 18:21, 20:3 and Deuteronomy 12:30–31, 18:10, the Torah contains a number of imprecations against and laws forbidding child sacrifice and human sacrifice in general. The Tanakh denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of Baal worshippers (e.g. Psalms 106:37). James Kugel argues that the Torah's specifically forbidding child sacrifice indicates that it happened in Israel as well.[40] The biblical scholar Mark S. Smith argues that the mention of "Tophet" in Isaiah 30:27–33 indicates an acceptance of child sacrifice in the early Jerusalem practices, to which the law in Leviticus 20:2–5 forbidding child sacrifice is a response.[41] Some scholars have stated that at least some Israelites and Judahites believed child sacrifice was a legitimate religious practice.[42]

Numbers 31

In the aftermath of the War against the Midianites narrated in Numbers 31, the Israelites appear to be dedicating 32 captive Midianite virgin girls to be sacrificed to Yahweh as his share in the spoils of war. Template:Excerpt

Gehenna and Tophet

- Further information: Moloch

The most extensive accounts of child sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible refer to those carried out in Gehenna by two kings of Judah, Ahaz and Manasseh of Judah.[43]

Jephthah's daughter

In the Book of Judges, chapter 11, the figure of Jephthah makes a vow to God, saying, "If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering" (as worded in the New International Version). Jephthah succeeds in winning a victory, but when he returns to his home in Mizpah he sees his daughter, dancing to the sound of timbrels, outside. After allowing her two months preparation, Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah kept his vow. According to the commentators of the rabbinic Jewish tradition, Jepthah's daughter was not sacrificed but was forbidden to marry and remained a spinster her entire life, fulfilling the vow that she would be devoted to the Lord.[44] The 1st-century CE Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, however, understood this to mean that Jephthah burned his daughter on Yahweh's altar,[45] whilst pseudo-Philo, late first century CE, wrote that Jephthah offered his daughter as a burnt offering because he could find no sage in Israel who would cancel his vow. In other words, this story of human sacrifice is not an order or requirement by God, but the punishment for those who vowed to sacrifice humans.[46]

Phoenicia and Carthage

Various Greek and Roman sources describe and criticize the Carthaginians as engaging in the practice of sacrificing children by burning.[47] Classical writers describing some version of child sacrifice to "Cronos" (Baal Hammon) include the Greek historians Diodorus Siculus and Cleitarchus, as well as the Christian apologists Tertullian and Orosius.[48][49] These descriptions were compared to those found in the Hebrew Bible describing the sacrifice of children by burning to Baal and Moloch at a place called Tophet.[48] The ancient descriptions were seemingly confirmed by the discovering of the so-called "Tophet of Salammbô" in Carthage in 1921, which contained the urns of cremated children.[50] However, modern historians and archaeologists debate the reality and extent of this practice.[51][52] Some scholars propose that all remains at the tophet were sacrificed, whereas others propose that only some were.[53]

Archaeological evidence

The specific sort of open aired sanctuary described as a Tophet in modern scholarship is unique to the Punic communities of the Western Mediterranean.[54] Over 100 tophets have been found throughout the Western Mediterranean,[55] but they are absent in Spain.[56] The largest tophet discovered was the Tophet of Salammbô at Carthage.[50] The Tophet of Salammbô seems to date to the city's founding and continued in use for at least a few decades after the city's destruction in 146 B.C.E.[57] No Carthaginian texts survive that would explain or describe what rituals were performed at the tophet.[56] When Carthaginian inscriptions refer to these locations, they are referred to as bt (temple or sanctuary), or qdš (shrine), not Tophets. This is the same word used for temples in general.[58][55]

As far as the archaeological evidence reveals, the typical ritual at the Tophet - which, however, shows much variation - began by the burial of a small urn containing a child's ashes, sometimes mixed with or replaced by that of an animal, after which a stele, typically dedicated to Baal Hammon and sometimes Tanit was erected. In a few occasions, a chapel was built as well.[59] Uneven burning on the bones indicate that they were burned on an open air pyre.[60] The dead children are never mentioned on the stele inscriptions, only the dedicators and that the gods had granted them some request.[61]

While tophets fell out of use after the fall of Carthage on islands formerly controlled by Carthage, in North Africa they became more common in the Roman Period.[62] In addition to infants, some of these tophets contain offerings only of goats, sheep, birds, or plants; many of the worshipers have Libyan rather than Punic names.[62] Their use appears to have declined in the second and third centuries CE.[63]

Controversy

The degree and existence of Carthaginian child sacrifice is controversial, and has been ever since the Tophet of Salammbô was discovered in 1920.[64] Some historians have proposed that the Tophet may have been a cemetery for premature or short-lived infants who died naturally and then were ritually offered.[52] The Greco-Roman authors were not eye-witnesses, contradict each other on how the children were killed, and describe children older than infants being killed as opposed to the infants found in the tophets.[50] Accounts such as Cleitarchus's, in which the baby dropped into the fire by a statue, are contradicted by the archaeological evidence.[65] There are not any mentions of child sacrifice from the Punic Wars, which are better documented than the earlier periods in which mass child sacrifice is claimed.[50] Child sacrifice may have been overemphasized for effect; after the Romans finally defeated Carthage and totally destroyed the city, they engaged in postwar propaganda to make their archenemies seem cruel and less civilized.[66] Matthew McCarty argues that, even if the Greco-Roman testimonies are inaccurate "even the most fantastical slanders rely upon a germ of fact."[65]

Many archaeologists argue that the ancient authors and the evidence of the Tophet indicates that all remains in the Tophet must have been sacrificed. Others argue that only some infants were sacrificed.[53] Paolo Xella argues that the weight of classical and biblical sources indicate that the sacrifices occurred.[67] He further argues that the number of children in the tophet is far smaller than the rate of natural infant mortality.[68] In Xella's estimation, prenatal remains at the tophet are probably those of children who were promised to be sacrificed but died before birth, but who were nevertheless offered as a sacrifice in fulfillment of a vow.[69] He concludes that the child sacrifice was probably done as a last resort and probably frequently involved the substitution of an animal for the child.[70]

The practice of child sacrifice among Canaanite groups is attested by numerous sources spanning over a millennium. One example is in the writings of Diodorus Siculus:

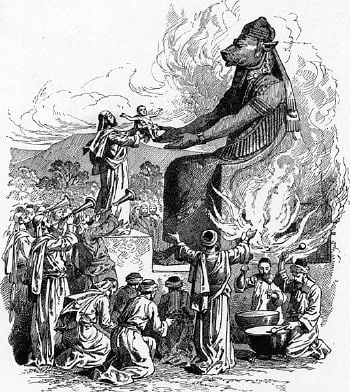

"They also alleged that Kronos had turned against them inasmuch as in former times they had been accustomed to sacrifice to this god the noblest of their sons, but more recently, secretly buying and nurturing children, they had sent these to the sacrifice; and when an investigation was made, some of those who had been sacrificed were discovered to have been substituted by stealth... In their zeal to make amends for the omission, they selected two hundred of the noblest children and sacrificed them publicly; and others who were under suspicion sacrificed themselves voluntarily, in number not less than three hundred. There was in the city a bronze image of Kronos, extending its hands, palms up and sloping towards the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire. It is probable that it was from this that Euripides has drawn the mythical story found in his works about the sacrifice in Tauris, in which he presents Iphigeneia being asked by Orestes: "But what tomb shall receive me when I die? A sacred fire within, and earth's broad rift." Also the story passed down among the Greeks from ancient myth that Cronus did away with his own children appears to have been kept in mind among the Carthaginians through this observance." Library 20.1.4

"Again, would it not have been far better for the Carthaginians to have taken Critias or Diagoras to draw up their law-code at the very beginning, and so not to believe in any divine power or god, rather than to offer such sacrifices as they used to offer to Cronos? These were not in the manner that Empedocles describes in his attack on those who sacrifice living creatures: "Changed in form is the son beloved of his father so pious,Who on the altar lays him and slays him. What folly!" No, but with full knowledge and understanding they themselves offered up their own children, and those who had no children would buy little ones from poor people and cut their throats as if they were so many lambs or young birds; meanwhile the mother stood by without a tear or moan; but should she utter a single moan or let fall a single tear, she had to forfeit the money, and her child was sacrificed nevertheless; and the whole area before the statue was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums so that the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people." Moralia 2, De Superstitione 3

"With us, for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos, as I daresay you yourself have heard." (Minos 315)

"And from then on to the present day they perform human sacrifices with the participation of all, not only in Arcadia during the Lykaia and in Carthage to Kronos, but also periodically, in remembrance of the customary usage, they spill the blood of their own kin on the altars, even though the divine law among them bars from the rites, by means of perirrhanteria and the herald's proclamation, anyone responsible for the shedding of blood in peacetime."[71]

". . . was chosen as a . . . sacrifice for the city. For from ancient times the barbarians have had a custom of sacrificing human beings to Kronos."

Quintus Curtius Rufus:

"Some even proposed renewing a sacrifice which had been discontinued for many years, and which I for my part should believe to be by no means pleasing to the gods, of offering a freeborn boy to Saturn —this sacrilege rather than sacrifice, handed down from their founders, the Carthaginians are said to have performed until the destruction of their city—and unless the elders, in accordance with whose counsel everything was done, had opposed it, the awful superstition would have prevailed over mercy. But necessity, more inventive than any art, introduced not only the usual means of defence, but also some novel ones." History of Alexander IV.III.23

"In Africa infants used to be sacrificed to Saturn, and quite openly, down to the proconsulate of Tiberius, who took the priests themselves and on the very trees of their temple, under whose shadow their crimes had been committed, hung them alive like votive offerings on crosses; and the soldiers of my own country are witnesses to it, who served that proconsul in that very task. Yes, and to this day that holy crime persists in secret." Apology 9.2-3

Philo of Byblos:

"Among ancient peoples in critically dangerous situations it was customary for the rulers of a city or nation, rather than lose everyone, to provide the dearest of their children as a propitiatory sacrifice to the avenging deities. The children thus given up were slaughtered according to a secret ritual. Now Kronos, whom the Phoenicians call El, who was in their land and who was later divinized after his death as the star of Kronos, had an only son by a local bride named Anobret, and therefore they called him Ieoud. Even now among the Phoenicians the only son is given this name. When war’s gravest dangers gripped the land, Kronos dressed his son in royal attire, prepared an altar and sacrificed him."[72]

Lucian:

"There is another form of sacrifice here. After putting a garland on the sacrificial animals they hurl them down alive from the gateway and the animals die from the fall. Some even throw their children off the place, but not in the same manner as the animals. Instead, having laid them in a pallet, they drop them down by hand. At the same time they mock them and say that they are oxen, not children."[73]

Cleitarchus:

"And Kleitarchos says the Phoenicians, and above all the Carthaginians, venerating Kronos, whenever they were eager for a great thing to succeed, made a vow by one of their children. If they would receive the desired things, they would sacrifice it to the god. A bronze Kronos, having been erected by them, stretched out upturned hands over a bronze oven to burn the child. The flame of the burning child reached its body until, the limbs having shriveled up and the smiling mouth appearing to be almost laughing, it would slip into the oven. Therefore the grin is called “sardonic laughter,” since they die laughing."[74]

"The Phoenicians too, in great disasters whether of wars or droughts, or plagues, used to sacrifice one of their dearest, dedicating him to Kronos. And the ‘Phoenician History,’ which Sanchuniathon wrote in Phoenician and which Philo of Byblos translated into Greek in eight books, is full of such sacrifices."[75]

And in the Books of Kings:

"When the king of Moab saw that the battle had gone against him, he took with him seven hundred swordsmen to break through to the king of Edom, but they failed. Then he took his firstborn son, who was to succeed him as king, and offered him as a sacrifice on the city wall. The fury against Israel was great; they withdrew and returned to their own land." (2 Kings 3:26-27)

At Carthage, a large cemetery exists that combines the bodies of both very young children and small animals, and those who assert child sacrifice have argued that if the animals were sacrificed, then so too were the children.[76] Recent archaeology, however, has produced a detailed breakdown of the ages of the buried children and, based on this and especially on the presence of prenatal individuals – that is, still births – it is also argued that this site is consistent with burials of children who had died of natural causes in a society that had a high infant mortality rate, as Carthage is assumed to have had. That is, the data support the view that Tophets were cemeteries for those who died shortly before or after birth.[76] Conversely, Patricia Smith and colleagues from the Hebrew University and Harvard University show from the teeth and skeletal analysis at the Carthage Tophet that infant ages at death (about two months) do not correlate with the expected ages of natural mortality (perinatal), apparently supporting the child sacrifice thesis.[77]

Greek, Roman and Israelite writers refer to Phoenician child sacrifice. Skeptics suggest that the bodies of children found in Carthaginian and Phoenician cemeteries were merely the cremated remains of children that died naturally.[78] Sergio Ribichini has argued that the Tophet was "a child necropolis designed to receive the remains of infants who had died prematurely of sickness or other natural causes, and who for this reason were "offered" to specific deities and buried in a place different from the one reserved for the ordinary dead".[79]

According to Stager and Wolff, in 1984, there was a consensus among scholars that Carthaginian children were sacrificed by their parents, who would make a vow to kill the next child if the gods would grant them a favor: for instance that their shipment of goods was to arrive safely in a foreign port.[80]

Europe

The Minoan civilization, located in ancient Crete, is widely accepted as the first civilization in Europe. An expedition to Knossos by the British School of Athens, led by Peter Warren, excavated a mass grave of sacrifices, particularly children, and unearthed evidence of cannibalism.[81][82]

clear evidence that their flesh was carefully cut away, much in the manner of sacrificed animals. In fact, the bones of slaughtered sheep were found with those of the children... Moreover, as far as the bones are concerned, the children appear to have been in good health. Startling as it may seem, the available evidence so far points to an argument that the children were slaughtered and their flesh cooked and possibly eaten in a sacrifice ritual made in the service of a nature deity to assure an annual renewal of fertility.[83][84]

Additionally, Rodney Castleden uncovered a sanctuary near Knossos where the remains of a 17-year-old were found sacrificed.

His ankles had evidently been tied and his legs folded up to make him fit on the table... He had been ritually murdered with the long bronze dagger engraved with a boar's head that lay beside him.[85]

At Woodhenge, a young child was found buried with its skull split by a weapon. This has been interpreted by the excavators as child sacrifice,[86] as have other human remains.

The Ver Sacrum ("A Sacred Spring") was a custom by which a Greco-Roman city would devote and sacrifice everything born in the spring, whether animal or human, to a god, in order to relieve some calamity.[87]

Africa

- Further information: Witchcraft accusations against children in Africa

South Africa

The continued murder of black children of all ages, for body parts with which to make muti, for purposes of witchcraft, still occurs in South Africa. Muti murders occur throughout South Africa, especially in rural areas. Traditional healers or witch doctors often grind up body parts and combine them with roots, herbs, seawater, animal parts, and other ingredients to prepare potions and spells for their clients.[88]

Uganda

In the early 21st century Uganda has experienced a revival of child sacrifice. In spite of government attempts to downplay the issue, an investigation by the BBC into human sacrifice in Uganda found that ritual killings of children are more common than Ugandan authorities admit.[89] There are many indicators that politicians and politically connected wealthy businessmen are involved in sacrificing children in practice of traditional religion, which has become a commercial enterprise.[90]

Notes

- ↑ LacusCurtius • Greek and Roman Sacrifices (Smith's Dictionary, 1875).

- ↑ Guy Strousma, "The End of Sacrifice" in The Making of the Abrahamic Religions in Late Antiquity (Oxford 2015). Academia link.

- ↑ Ortíz C., Ponciano; Rodríguez, María del Carmen (1999) "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space" {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds. Grove, D. C.; Joyce, R. A., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C., p. 225 - 254 (specifically p. 249).

- ↑ Marí, Carlos (27 December 2005). Evidencian sacrificios humanos en Comalcaco: Hallan entierro de menores mayas. Reforma.

- ↑ Scherer, Andrew K. (2015-01-01). Mortuary Landscapes of the Classic Maya: Rituals of Body and Soul. University of Texas Press. DOI:10.7560/300510.8.pdf. ISBN 9781477300510.

- ↑ Stuart, David (2003). La ideología del sacrificio entre los mayas. Arqueología Mexicana XI, 63: 24–29.

- ↑ Serrano Sanchez, Carlos (1993). "Funerary Practices and Human Sacrifice in Teotihuacan Burials". Kathleen Berrin, Esther Pasztory, eds., Teotihuacan, Art from the City of the Gods, Thames and Hudson, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Template:ISBN, p. 113–114.

- ↑ Monica Medel (April 2007). Mexico finds bones suggesting Toltec child sacrifice. Reuters.

- ↑ Duverger, Christian (2005). La flor letal. Fondo de cultura económica, 128–29.

- ↑ Cortes. Letter 105.

- ↑ Motolinia, History of the Indies, 118–119

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ "Aztec tower of human skulls uncovered in Mexico City", BBC News, 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Duverger, Christian (2005). La flor letal. Fondo de cultura económica, 128–29.

- ↑ Talavera González, Jorge Arturo (2003). Evidencias de sacrificio humano en restos óseos. Arqueología Mexicana XI, 63: 30–34.

- ↑ Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España, ed. a cargo de Ángel Ma. Garibay (México: Editorial Porrúa, 2006). p. 97

- ↑ "Steve Bourget on Sacrifice, Violence, and Ideology Among the Moche", June 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Human Sacrifices at the Huaca de la Luna".

- ↑ "Archaeologists in Peru unearth 227 bodies in the biggest-ever discovery of child sacrifice", August 29, 2019.

- ↑ "Peru child sacrifice discovery may be largest in history", BBC News, 28 April 2018.

- ↑ Reinhard, Johan (November 1999). A 6,700 metros niños incas sacrificados quedaron congelados en el tiempo. National Geographic, Spanish version: 36–55.

- ↑ "Secretaría de Cultura de Salta Argentina – Mission and Origins". {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}. Maam.culturasalta.gov.ar (2007-12-16). Retrieved on 2010-12-14.

- ↑ Article and slide show on the Llullaillaco mummies. The New York Times.

- ↑ Inca mummies: Child sacrifice victims fed drugs and alcohol. BBC.

- ↑ De los timoto-cuicas a la invisibilidad del indigena andino y a su diversidad cultural.

- ↑ Timoto-Cuicas.

- ↑ http://gallery.sjsu.edu/sacrifice/precolumbian.html {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} - "Pre-Columbian Andean Sacrifices"

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20080506113520/http://www.exn.ca/mummies/story.asp?id=1999041452 – Discovery Channel - Archive.org article

- ↑ Fleur, Nicholas St, "Massacre of Children in Peru Might Have Been a Sacrifice to Stop Bad Weather", The New York Times, 2019-03-06. (written in en-US)

- ↑ (2019) A mass sacrifice of children and camelids at the Huanchaquito-Las Llamas site, Moche Valley, Peru. PLOS ONE 14 (3): e0211691.

- ↑ Hundreds of children and llamas sacrificed in a ritual event in 15th century Peru: The largest sacrifice of its kind known from the Americas was associated with heavy rainfall and flooding (in en).

- ↑ (2019-03-06) A mass sacrifice of children and camelids at the Huanchaquito-Las Llamas site, Moche Valley, Peru. PLOS ONE 14 (3): e0211691.

- ↑ http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/18495/1/articulo3.pdf De los timoto-cuicas a la invisibilidad del indigena andino y a su diversidad cultural

- ↑ http://issuu.com/bnahem/docs/revista_digital_timoto_cuicas Timoto-Cuicas

- ↑ Micah 6:7

- ↑ Micah 6:8

- ↑ First Person: Human Sacrifice to an Ammonite God? (in en) (2014-09-23).

- ↑ "Olat Reiya", p. 93.

- ↑ Irving Greenberg. 1988. The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. New York : Summit Books. p.195.

- ↑ " It was not just among Israel's neighbours that child sacrifice was countenanced, but apparently within Israel itself. Why else would biblical law specifically forbid such things – and with such vehemence?" However, Chananya Goldberg argues that such a point is illogical - for if it were to be accepted, one would be forced to assume that, within Israel, people killed, stole and injured with impunity. James Kugel (2008). How to Read the Bible, p. 131.

- ↑ " Smith also cites Ezekiel 20:25–26 as an example of where Yahweh refers to "the sacrifice of every firstborn". These passages indicate that in the seventh-century child sacrifice was a Judean practice performed in the name of YHWH...In Isaiah 30:27–33 there is no offense taken at the Tophet, the precinct of child sacrifice. It would appear that the Jerusalemite cult included child sacrifice under Yahwistic patronage; it is this that Leviticus 20:2–5 deplores." Mark S. Smith (2002). The early history of God: Yahweh and the other deities in ancient Israel, pp. 172–178.

- ↑

- Susan Nidditch (1993). War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence, Oxford University Press, p. 47. "While there is considerable controversy about the matter, the consensus over the last decade concludes that child sacrifice was a part of ancient Israelite religion to large segments of Israelite communities of various periods." However, no mainstream Jewish sources allow child-sacrifice, even in theory. All mainstream Jewish sources state, or imply, that such an act is abhorrent.

- Susan Ackerman (1992). Under Every Green Tree: Popular Religion in Sixth-Century Judah, Scholars Press, p. 137. "the cult of child sacrifice was felt in some circles to be a legitimate expression of Yawistic faith."

- Francesca Stavrakopoulou (2004). "King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities', p283. "Though the Hebrew Bible portrays child sacrifice as a foreign practice, several texts indicates that it was a native element of Judahite deity-worship."

- ↑ Christopher B. Hays Death in the Iron Age II & in First Isaiah 2011 p181 "Efforts to show that the Bible does not portray actual child sacrifice in the Molek cult, but rather dedication to the god by fire, have been convincingly disproved. Child sacrifice is well attested in the ancient world, especially in times of crisis."

- ↑ Radak, Book of Judges 11:39; Metzudas Dovid ibid

- ↑ Brenner, Athalya (1999). Judges: a feminist companion to the Bible. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84127-024-1.

- ↑ Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press.

- ↑ Warmington 1995, p. 453.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Stager & Wolff 1984.

- ↑ Quinn 2011, pp. 388-389.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Hoyos 2021, p. 17.

- ↑ Schwartz & Houghton 2017, p. 452.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Holm 2005, p. 1734.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Schwartz & Houghton 2017, pp. 443-444.

- ↑ Xella 2013, p. 259.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 McCarty 2019, p. 313.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Bonnet 2011, p. 373.

- ↑ Bonnet 2011, p. 379.

- ↑ Bonnet 2011, p. 374.

- ↑ Bonnet 2011, pp. 378-379.

- ↑ McCarty 2019, p. 315.

- ↑ Bonnet 2011, pp. 383-384.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 McCarty 2019, p. 321.

- ↑ McCarty 2019, p. 322.

- ↑ McCarty 2019, p. 316.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 McCarty 2019, p. 317.

- ↑ Macchiarelli & Bondioli 2012.

- ↑ Xella 2013, p. 266.

- ↑ Xella 2013, p. 268.

- ↑ Xella 2013, pp. 270-271.

- ↑ Xella 2013, p. 273.

- ↑ Dennis Hughes, Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece, Taylor & Francis 2013, p116

- ↑ fragment in Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 1.10.44=4.16.11

- ↑ Heath Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel, Eisenbruans 2017, p43

- ↑ Heath Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel, Eisenbrauns 2017, p137

- ↑ Albert Baumgartner, The Phoenician History of Philo of Byblos: A Commentary, Brill, 1981, p244

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0009177

- ↑ (2013) Cemetery or sacrifice? Infant burials at the Carthage Tophet: Age estimations attest to infant sacrifice at the Carthage Tophet. Antiquity 87 (338): 1191–1199.

- ↑ (2001) The Phoenicians. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761403098. “child sacrifice.”

- ↑ Sergio Ribichini, "Beliefs and Religious Life" in Moscati, Sabatino (ed), The Phoenicians, 1988, p.141

- ↑ Stager, Lawrence (1984). Child sacrifice in Carthage: religious rite or population control?. Journal of Biblical Archeological Review January: 31–46.

- ↑ Rodney Castleden, Minoans. Life in Bronze Age Crete (illustrated by the author), London-New York, Routledge,pp. 170–173.

- ↑ (4 January 2002) Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete. ISBN 9781134880645.

- ↑ Peter Warren, "Knossos: New Excavations and Discoveries," Archaeology (July / August 1984), pp. 48–55.

- ↑ Minoan Crete and Ecstatic Religion: Preliminary Observations on the 1979 Excavations at Knossos. Front Cover. Peter Warren. 1981

- ↑ Rodney Castleden, The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the "Palace of Minos" at Knossos, 2012, pp. 121–22.

- ↑ Ronald Hutton, The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy, Template:ISBN, p. 90.

- ↑ LacusCurtius • Ver Sacrum (Smith's Dictionary, 1875).

- ↑ (2008)New magic for new times: muti murder in democratic South Africa. Studies of Tribes and Tribals Special Volume No. 2: 43–53.

- ↑ Tim Whewell, "Witch-doctors reveal extent of child sacrifice in Uganda", BBC News, 7 January 2010

- ↑ Rogers, Chris 2011. Where child sacrifice is a business, BBC News Africa (11 October): https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-15255357#story_continues_1

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

All links retrieved

- 5 things you need to know about child sacrifice in Uganda World Vision

- Mass child sacrifice discovery may be largest in Peru BBC

- Ancient Carthaginians really did sacrifice their children University of Oxford

- New evidence of ancient child sacrifice found in Turkey Natural History Museum

- Why the Incas offered up child sacrifices The Observer

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.