Centaur

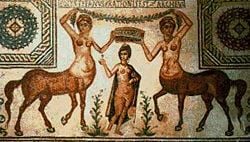

In Greek mythology, the centaurs (Greek: Κένταυροι) are a race of creatures half human and half horse. In early Attic vase-paintings, they are depicted as the head and torso of a man with his waist joined to the horse's withers, where the horse's neck would be. This human and animal combination has lead many writers to treat them as "liminal" beings, caught between the two natures of feral animalism and cogent humanity.

Etymology

The etymology of the word centaur from the Greek word kentauros could be understood as ken - tauros, which means "piercing bull." It is also possible that this word in fact comes from the Mesopotamian word for Centaurus, the constellation that in Mesopotamian culture depicted an epic battle of Gods. The Greeks later re-named the constellation for its depiction of a man riding a horse, the significance of which has been suggested as a collective but vague memory of horse riders from Thessaly that at one time invaded Greece.[1]

Origin

The most common theory holds that the idea of centaurs came from the first reaction of a non-riding culture, as in the Minoan Aegean world, to nomads who were mounted on horses. This theory suggests that such riders would appear as half-man, half-animal. Bernal Díaz del Castillo reported that the Aztecs had this misapprehension about Spanish cavalrymen.[2]

Horse taming and horseback culture evolved first in the southern steppe grasslands of Central Asia, perhaps approximately in modern Kazakhstan. The Lapith tribe of Thessaly, who were the kinsmen of the Centaurs in myth, were described as the inventors of horse-back riding by Greek writers. The Thessalian tribes also claimed their horse breeds were descended from the centaurs.

Anthropologist and writer Robert Graves speculated that the centaurs of Greek myth were a dimly-remembered, pre-Hellenic fraternal earth cult who had the horse as a totem.

Of the various Classical Greek authors who mentioned centaurs, Pindar was the first who describes what is undoubtedly a combined monster. Previous authors such as Homer only used words such as Pheres (beasts) that could also mean ordinary savage men riding ordinary horses. However, contemporaneous representations of hybrid centaurs can be found in archaic Greek art.

Myths

According to Greek Mythology, the centaurs descended from Centaurus, who mated with the Magnesian mares. Centaurus was the son of either Ixion and Nephele (the cloud made in the image of Hera) or of Apollo and Stilbe, daughter of the river god Peneus. In the latter version of the story his twin brother was Lapithus, ancestor of the Lapiths, thus making the two warring peoples cousins.

The most popular myth featuring Centaurs is the story of the wedding of Hippodamia, and Pirithous, king of the Lapithae. Kin to Hippodamia, the centaurs attended the wedding, but became so drunk and riotous at the ceremony that they attempted to ride off with the bride and other women. A large and bloody battle ensued, and despite their size and strength, the centaurs were defeated and driven away.[3] The strife among these cousins is interpreted as similar to the defeat of the Titans by the Olympian gods—the contests with the Centaurs typify the struggle between civilization and barbarism.

Other myths include the story of Atalanta, a girl raised in the wild by animals who slayed two centaurs who threatened her, thanks to her excellent archery skills. The most famous centaur was Chiron, a old, wise and legendarily gifted centaur. He is featured in many stories, being credited with raising Aesculapis the physician and Actaeon the hunter, as well as teaching the greatest of Greek warriors, Achilles. There are two conflicting stories of his death. The first involves and accidental injury caused by Hercules that was so painful but not mortal that Zeus allowed Chiron to die with dignity. The other story involves Chiron's willful sacrificing of his life in order to save Prometheus from being punished by Zeus.[3]

Centaurs in Artwork

Vignettes of the battle between Lapiths and Centaurs were sculpted in bas-relief on the frieze of the Parthenon, which was dedicated to wise Athena,[4] are favorite subjects of Greek art.[5]

The mythological episode of the centaur Nessus carrying off Deianira, the bride of Heracles, also provided Giambologna (1529-1608), a Flemish sculptor whose career was spent in Italy, splendid opportunities to devise compositions with two forms in violent interaction. He made several versions of Nessus carrying off Deianira, represented by examples in the Louvre, the Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden, the Frick Collection, New York City, and the Huntington Library, San Marino, California. His followers, like Adriaen de Vries and Pietro Tacca, continued to make countless repetitions of the subject. When Carrier-Belleuse tackled the same play of forms in the nineteenth century he titled it Abduction of Hippodameia.

Centaurs in fiction

Centaurs have appeared many times and in many places literature and popular fiction. The Centaur Inn featured in Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors. Centaurs are featured in C. S. Lewis' The Chronicles of Narnia, and numerous fantasy novels by a variety of twentieth century authors.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ "Centaur" The Compact Edition of The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1971

- ↑ Stuart Chase, Mexico: A Study of Two Americas, Chapter IV (University of Virginia Hypertext), accessed 24 April 2006.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hamilton, Edith. 1998. Mythology. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316341517

- ↑ Apollodorus, ii. 5; Diod. Sic. IV, li

- ↑ Colvin, Sidney. Journal of Hellenic Studies, I, 1881, and the exhaustive article in Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie

External links

- "Kentauroi Thessalioi" Theoi Project. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.