Capital punishment

Capital punishment, or the death penalty, is the execution of a convicted criminal by the State as punishment for the most serious crimes—known as capital crimes. The word "capital" is derived from the Latin "capitalis," which means "concerning the head"; therefore, to be subjected to capital punishment means to figuratively lose one's head.

Historically, the death penalty was used to punish criminals and to suppress political and religious dissenters. Use of the death penalty greatly declined in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and today it has been abolished in many countries, particularly in Europe and Latin America. The formerly liberal use of the death penalty to punish political and religious dissenters and petty criminals is now universally condemned. In countries where it is retained—the United States, most of the Caribbean, and the democracies of Asia and Africa—it is reserved as a punishment for only the most serious crimes: premeditated murder, espionage, treason, and in some countries, drug trafficking.

Among nondemocratic countries the death penalty is still widely used. In China human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are punished by the death penalty. In some Islamic countries, sexual crimes including adultery and sodomy carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy, the formal renunciation of Islam. In times of war or martial law, even in democracies military justice has meted out death sentences for offenses such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny [1].

Yet capital punishment remains a contentious issue, even where is employed to punish only the most serious crimes. Supporters argue that it deters crime, prevents recidivism, and is an appropriate punishment for the crime of murder. Opponents argue that it does not deter criminals more than would life imprisonment, that it violates human rights, leads to executions of some who are wrongfully convicted, and discriminates against minorities and the poor.

History

Long before there were historical records, tribal societies enforced justice by principle of lex talionis: "an eye for an eye, a life for a life." Thus, death was the appropriate punishment for murder. The biblical expression of this principle (Exodus 21:24) is understood by modern scholars to be a legal formula to guide judges in imposing the appropriate sentence. However, it hearkens back to tribal society where it was understood to be the responsibility of the victim's relatives to exact vengeance upon the perpetrator or a member of his family. The person executed did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime because the system was based on tribes, not individuals. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on the state or organized religion. "Acts of retaliation underscore the ability of the social collective to defend itself and demonstrate to enemies (as well as potential allies) that injury to property, rights, or the person will not go unpunished."[2]

Revenge killings are still accepted legal practice in tribally organized societies, for example in the Middle East and Africa, surviving alongside more advanced legal systems. However, when it is not well arbitrated by the tribal authorities, or when the murder and act of revenge cross tribal boundaries, a revenge killing for a single crime can provoke retaliation and escalate into a blood feud, or even a low-level war of vendetta (as in contemporary Iraq or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict).

Compared to revenge killings, use of formal executions by a strong governing authority was a small step forward. The death penalty was authorized in the most ancient written law codes. For example, the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1800 B.C.E.) set different punishments and compensation according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The Old Testament lays down the death penalty for murder, kidnapping, magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.[3]

Nevertheless, with the expansion of state power, the death penalty came to be used more frequently as a means to enforce that power. For example in Ancient Greece, the Athenian legal system was first written down by Draco in about 621 B.C.E.; there the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes. The word "draconian" derives from Draco's laws. Similarly, in medieval and early modern Europe, the death penalty was also used as a generalized form of punishment. For example, in 1700s Britain, there were 222 crimes which were punishable by death, including crimes such as cutting down a tree or stealing an animal.[4]

The emergence of modern democracies brought with it the concepts of natural rights and equal justice for all citizens. At the same time there were religious developments within Christianity that elevated the value of every human being as a child of God. In the nineteenth century came the movement to reform the prison system and establish "penitentiaries" where convicts could be reformed into good citizens. These developments made the death penalty seem excessive and increasingly unnecessary as a deterrent for the prevention of minor crimes such as theft. As well, in countries like Britain, law enforcement officials became alarmed when juries tended to acquit non-violent felons rather than risk a conviction that could result in execution.

The twentieth century was one of the bloodiest of the human history. The World Wars entailed massive loss of life, not only in combat, but also by summary executions of enemy combatants. Moreover, authoritarian states—those with fascist or communist governments—employed the death penalty as a means of political oppression. In the Soviet Union, in Nazi Germany and in Communist China, millions of civilians were executed by the state apparatus. In Latin America, tens of thousands of people were rounded up and executed by the military in their counterinsurgency campaigns. Partly as a response to these excesses, civil organizations began to to increasing emphasize the securing of human rights and abolition of the death penalty.

Methods of execution

Methods of execution have varied over time, and include:

- Burning, especially for religious heretics and witches on the stake

- Burial alive (also known as the pit)

- Crucifixion

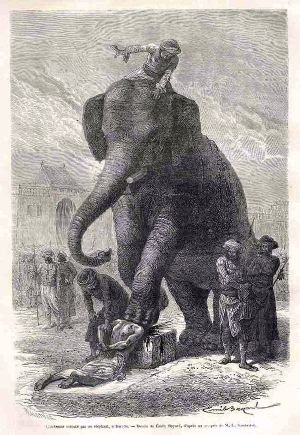

- Crushing by a weight

- Decapitation or beheading (as by sword, axe, or guillotine)

- Drawing and quartering (Considered by many to be the most cruel of punishments)]

- Electric chair

- Gas chamber

- Hanging

- Impalement

- Lethal injection

- Poisoning (as in the execution of Socrates)

- Shooting by firing squad (common for military executions)

- Shooting by a single shooter (performed on a kneeling prisoner, as in China)

- Stoning

Movements towards "humane" execution

The trend in recent history has been to move to less painful, or more "humane" methods of capital punishment. France at the end of the eighteenth century adopted the guillotine for this reason. Britain in the early 19th century banned drawing and quartering. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by dangling him from the back of a moving cart, which causes a slow death by suffocation, was replaced by hanging where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. In the United States the electric chair and the gas chamber were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging; and these have since been superseded by lethal injection, which today is criticized as being too painful.

The death penalty worldwide

At one time capital punishment was used in almost every part of the globe; but over the last few decades many countries have abolished it. Amnesty International classifies countries in four categories. 71 countries still maintain the death penalty in both law and practice. 87 countries have abolished it completely; 11 retain it, but only for crimes committed in exceptional circumstances (such as crimes committed in time of war). 27 other countries maintain laws permitting the capital punishment for serious crimes but have allowed the death penalty to fall into disuse. Among countries that maintain the death penalty, only 7 execute juveniles (under 18). Finally, it is not unknown for countries to practice extrajudicial execution sporadically or systematically outside their own formal legal frameworks.

China performed more than 3400 executions in 2004, amounting to more than 90% of executions worldwide. Iran performed 159 executions in 2004.[1]. The United States performed 60 executions in 2005. Texas conducts more executions than any of the other states in the United States that still permit capital punishment, with 370 executions between 1976 and 2006. Singapore has the highest execution rate per capita, with 70 hangings for a population of about 4 million.

Where the death penalty was widely practiced a tool of political oppression in poor, undemocratic, and authoritarian states, movements grew strongest to abolish the practice. Abolitionist sentiment was widespread in Latin America in the 1980s, when democratic governments were replacing authoritarian regimes. Guided by its long history of Enlightenment and Catholic thought, the death penalty was soon abolished throughout most of the continent. Likewise, the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe was soon followed by popular aspirations to emulate neighboring Western Europe. In these countries, the public support for the death penalty is decreasing. Hence, there was not much objection when the death penalty was abolished as an entry condition for membership in the European Union. The European Union and the Council of Europe both strictly require member states not to practice the death penalty.

On the other hand, the rapidly industrializing democracies of Asia did not experience a history of excessive use of the death penalty by governments against their own people. In these countries the death penalty enjoys strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media. The same applies in African and Middle Eastern countries, where the support for the death penalty remains high.

The United States never had a history of excessive capital punishment, yet some states have banned capital punishment for decades (the earliest is Michigan, where it was abolished in 1843). In other states the death penalty is in active use. The death penalty in the United States remains a contentious issue. It is one of the few countries where there are contending efforts both to abolish and to retain the death penalty, fueled by active public discussion of its merits. Currently, 12 states and the District of Columbia ban capital punishment.

Juvenile capital punishment

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. The only countries that have executed juvenile offenders since 1990 include China, D.R. Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. and Yemen.[5]. The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005). In 2002, the United States Supreme Court outlawed the execution of individuals with mental retardation.[6]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles, has been signed and ratified by all countries except for the U.S. and Somalia [7]. The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to customary international law.

Public opinion

Both in abolitionist and retentionist democracies, the government's stance often has wide public support and receives little attention by politicians or the media. In countries that have abolished the death penalty, debate is sometimes revived by a spike in serious, violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, prompting some countries (such as Sri Lanka and Jamaica) to end their moratoriums on its use. In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived by a miscarriage of justice, though this more often leads to legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty.

A Gallup International poll from 2000 found that "Worldwide support was expressed in favour of the death penalty, with just more than half (52%) indicating that they were in favour of this form of punishment." Sentiment against the death penalty is strongest in Western Europe 34%/60% and Latin America 37%/55%. Support for the death penalty prevails in North America 66%/27%, Asia 63%/21%, Central and Eastern Europe 60%/29%, and Africa 54%/43%. [2]

In the U.S., surveys have long shown a majority in favor of capital punishment. An ABC News survey in July 2006 found 65 percent in favor of capital punishment, consistent with other polling since 2000.[8] About half the American public says the death penalty isn't imposed frequently enough and 60 percent believe it is applied fairly, according to a Gallup poll in May 2006.[3] Yet surveys also show the public is more divided when asked to choose between the death penalty and life without parole, or when dealing with juvenile offenders.[4][5] Roughly six in 10 tell Gallup they don't believe capital punishment deters murder and majorities believe at least one innocent person has been executed in the past five years.[6] [7]

The movement toward abolition of the death penalty

Modern opposition to the death penalty stems from the Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794), who wrote Dei Delitti e Delle Pene (On Crimes and Punishments) (1764). Beccaria, who preceded Jeremy Bentham as an exponent of Utilitarianism, aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, famous monarch of the Enlightenment and future Emperor of Austria, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Tuscany, the first permanent abolition in modern times. On November 30, 1786, after having de facto blocked capital executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000 Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on November 30 to commemorate the event.

The first democracy in recorded history to ban capital punishment was the state of Michigan, which did so on March 1, 1847. Its 160-year ban on capital punishment has never been repealed. The first country to ban capital punishment in its constitution was the Roman Republic, in 1849. Venezuela abolished the death penalty in 1863 and Portugal did so in 1867. The last execution in Portugal had taken place in 1846.

Several international organizations have made the abolition of the death penalty a requirement of membership, most notably the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe. The Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the Thirteenth Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights prohibit the death penalty. All countries seeking membership to the EU must abolish the death penalty, and those seeking to join the Council of Europe must either abolish it or at least declare a moratorium on its use. For example, Turkey, in its efforts to gain EU membership, suspended executions in 1984 and ratified Protocol 13 in 2006.

Otherwise, most existing international treaties categorically exempt death penalty from prohibition in case of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Among non-governmental organisations, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment.

Religious views

The official teachings of Judaism approve the death penalty in principle but the standard of proof required for application of death penalty is extremely stringent, and in practice it has been abolished by various Talmudic decisions, making the situations in which a death sentence could be passed effectively impossible and hypothetical.

Christian positions, as on many social issues, vary. Some interpret John 8:7, when Jesus rebuked those who were about to stone an adulterous woman to death, as a condemnation of the death penalty. In Matthew 26:52 Jesus also condemns the lex talionis, saying that all who take the sword will perish by the sword. Furthermore, the most egregious use of the death penalty was to kill the saints and prophets whom God sent to bring enlightenment to humanity. Jesus and Socrates were the two most outstanding victims of judicial use of the death penalty. Hence, Christians as well as Enlightenment thinkers have sought the abolition of capital punishment.

Mennonites and Quakers have long opposed the death penalty. The Lambeth Conference of Anglican and Episcopalian bishops condemned the death penalty in 1988. Contemporary Catholics also oppose the death penalty. The recent encyclicals Humanae Vitae and Evangelium Vitae set forth a position denouncing capital punishment alongside abortion and euthanasia as violations of the right to life. While capital punishment may sometimes be necessary if it is the only way to defend society from an offender, with today's penal system such a situation requiring an execution is either rare or non-existent. [9]

On the other hand, the traditional Catholic position was in support of capital punishment, as per the theology of Thomas Aquinas, who accepted the death penalty as a necessary deterrent and prevention method, but not as the means of vengeance. Both Martin Luther and John Calvin followed the traditional reasoning in favor of capital punishment, and the Augsburg Confession explicitly defends it. Some Protestant groups have cited Genesis 9:6 as the basis for permitting the death penalty [8][9].

Islamic law (Sharia) calls for the death penalty for a variety of offenses. However, the victim or the family of the victim has the right to pardon.

The Dalai Lama calls for a worldwide moratorium on use of the death penalty, based on his belief that even the most incorrigible criminal is capable of reform. [10]

The Hindu scriptures hold that the authorities have an obligation to punish criminals, even to the point of the death penalty, as a matter of Dharma and to protect society at large. Based on the doctrine of reincarnation, if the offender is punished for his crimes in this lifetime, he will not have to suffer the effects of that karma in a future life.

Capital punishment debate

Capital punishment, or the death penalty, is often the subject of controversy. Opponents of the death penalty argue that life imprisonment is an effective substitute, that capital punishment may lead to irreversible miscarriages of justice, or that it violates the criminal's right to life. Supporters insist that the penalty is justified (at least for murderers) by the principle of retribution, that life imprisonment is not an equally effective deterrent, and that the death penalty affirms society's condemnation of severe crimes. Some arguments revolve around empirical data, such as whether the death penalty is a more effective deterrent than life imprisonment, while others employ abstract moral judgements.

Ethical and philosophical discussions on capital punishment

Ethical debate of the death penalty can be split into two main philosophical contexts, a deontological (a priori) context and a utilitarian/consequentialist context. A priori argument can be further subcategorised into a "right" argument and a virtue argument.

The deontological objection to the death penalty asserts that the death penalty is "wrong" by its nature, mostly due to the fact that it amounts to the violation of the right to life, which should be universal. In philosophical debate, however, the virtue school tends to argue that the death penalty is also "wrong" on the ground that the process is cruel and inhumane. It brutalises the society at large and desensitises and dehumanizes participants of the judicial process. In particular, it extinguishes the possibility of rehabilitation and redemption of the perpetrator(s). Deontic justification to the death penalty, on the other hand, argues that the death penalty is "right" by nature, mostly on the ground that retribution against the violator of another life or liberty is "just". It naturally follow that not applying death penalty to heinous murder would be unjust. In virtue context, they point out that without proper retribution, the judicial system further brutalises the victim or victim's family and friends, which amounts to secondary victimisation. Moreover, the judicial process which applies the death penalty reinforces the sense of justice among participants as well as the citizens as a whole, and might even provide incentive for the convicted to own up to their crime.

Human rights

The concept of human rights originated from the natural rights formulated by the classical liberals of the Enlightenment period. However, over the centuries the concept has grown to become the dominant political, philosophical and legal principle in the world. Most anti-death penalty organisations, most notably Amnesty International, base their stance on human rights arguments.

Wrongful convictions

The death penalty is often opposed on the grounds that, because every criminal justice system is fallible, innocent people will inevitably be executed by mistake [11], and the death penalty is both irreversible and more severe than lesser punishments. The supporters of the death penalty point out that lesser punishments, including life imprisonment, can also be imposed in error and incarceration is also irreversible if the innocent dies in prison. Moreover, whether money is an acceptable compensation for long period of incarceration is a matter of subjective opinion. They also point out that, given significantly large number of people who are incarcerated rather than executed, it is more common for miscarriages of justice to occur in non-death penalty cases, though each individual execution is undoubtedly more severe, except arguably for a case where the innocent were incarcerated for his or her natural life. For supporters of the death penalty, failure for death penalty opponents to oppose life imprisonment (and sometimes incarceration) invalidates their argument.

The opponents of death penalty often argue that even a single case of an innocent person being executed is unacceptable. Most arguments about wrongful convictions proceed on the basis of empirical evidence and statistics. Opponents of the death penalty in the United States, for example, point to the fact that between 1973 and 2005, 122 people in 25 US states were released from death row when new evidence of their innocence emerged [12]. However, statistics are not necessarily a reliable measure of the actual problem of wrongful convictions. It is possible that many cases of innocent people being executed have gone undiscovered, as once an execution has occurred there is often insufficient motivation and finance to keep a case in the public eye. On the other hand, because in liberal democracies a suspect is considered innocent until proven guilty, the fact that a convict is exonerated and released from death row means merely that there is insufficient evidence to prove their guilt, rather than that they are necessarily innocent.

Some opponents of the death penalty believe that, while it is unacceptable as currently practiced, it would be permissible if criminal justice systems could be improved. However more staunch opponents insist that, as far as capital punishment is concerned, criminal justice is irredeemable. The US Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun, for example, famously wrote that it is futile to "tinker with the machinery of death". In addition to simple human fallibility, there are numerous more specific causes of wrongful convictions; for example:

- Convictions may rely solely on witness statements, which are vulnerable to being countered by forensic evidence. New forensic methods, such as DNA testing, have brought to light previously unavailable evidence and revealed errors in many old convictions [13].

- Suspects may receive poor legal representation. The ACLU argues that "the quality of legal representation [in the USA] is a better predictor of whether or not someone will be sentenced to death than the facts of the crime"[14].

- Improper procedure may be followed. For example, Amnesty International argues that, in Singapore, "the Misuse of Drugs Act contains a series of presumptions which shift the burden of proof from the prosecution to the accused. This conflicts with the universally guaranteed right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty" [15]. However, this refers to a situation when someone is being caught with drugs. In this situation, in almost any jurisdiction, the prosecution has a prima facie case. It may be possible to argue that the standard of proof should be raised to higher standard in case of the death penalty trial. However, many dispute the assertion that this fall into the definition of "improper procedure".

The proponents of death penalty argue that all these criticisms apply equally to life imprisonment, which imply that some innocents might have spent their entire life being incarcerated. Therefore, this would make the argument of substituting the death penalty with life imprisonment moot.

Right to life

Critics of the death penalty commonly argue that it is a violation of the right to life or of the "sanctity of life." Many national constitutions and international treaties guarantee the right to life; arguments based on these legal provisions are discussed below (#Legality). However, many also hold that the right to life is a human right or natural right that exists independently of laws made by people. The proponents of the death penalty commonly counter that the critics do not appear to have a problem with a violation of the right to liberty, as in the case of incarceration as substitute. Therefore, they implicitly accept that exceptions can be made to natural rights. Therefore, the proponents view the critics' argument to be nonessential.

The right to life and the right to liberty was stated to be a natural right by 17th-century philosopher John Locke, who specifically accepted incarceration and execution in response to violation of right to life and liberty. Right to life and liberty are also declared to be human rights by famous documents such as the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the American Declaration of Independence, while actual U.N. treaties specifically exempt the death penalty in certain circumstances, including serious criminal offence.

Opponents of the death penalty argue that the right to life demands that a life only be taken in exceptional circumstances, such as in self-defence or as an act of war, and therefore that it violates the right to life of a criminal if she or he is executed. Critics often hold that, because life is an unalienable right, the criminal cannot forfeit the right by committing a crime. Supporters of the death penalty point out that opponents do not actually consider right to be inviolable. It is only right to life which is specifically inviolable while other rights, such as right to liberty can be violated to the extent that someone can be forced to spend the entire course of natural life being incarcerated. Proponents of the death penalty argue that this is an arbitrary argument. The proponents insist that no right is absolute, and so can be forfeited especially by a criminal who takes the life of another. Locke, Kant and other enlightenment thinkers who originated the concept of human rights argued that people forfeit the right to life when they take life of another. Some proponents of the death penalty go further to argue that the death penalty is necessary to protect the right to life of the victims of murder, either because this entails the right of a victim to have their murder avenged, or because the death penalty is necessary to prevent, by means of incapacitation or deterrence, future murders.

Inhumanity

Opponents of the death penalty usually argue that is inhumane, or even that it constitutes a form of torture. Those who make this argument commonly insist that, in addition to violating the right to life, the death penalty is also contrary to the right to be free from torture or inhumane treatment. This right is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and many other documents.

Some arguments about the humaneness of the death penalty apply only to specific methods of execution. Of methods of execution currently in use the electric chair and the gas chamber are widely seen as producing great pain and suffering in the victim. All U.S. jurisdictions that currently use the gas chamber offer lethal injection as an alternative and, save Nebraska, the same is also true of the electric chair. Lethal injection has become widely used in the United States in an effort to make the death penalty more humane. However there are fears that, because the cocktail of drugs used in many executions paralyses the victim for a period before ending her or his life, victims may endure suffering not apparent to observers. The suffering caused by a method of execution is also often exacerbated in the case of "botched" executions. Amnesty International has highlighted lethal injection as the most frequently "botched" method of execution, noting practices such as crude "cut-downs" into prisoners' arms when a vein cannot be found [16]. Medical staff, who might have expertise in minimising suffering, do not normally assist with executions, as this would be a violation of the Hippocratic Oath [17]. Those who make this argument also insist that the knowledge of ones impending death causes tremendous psychological suffering. This suffering, exacerbated by the long periods often spent by convicts in the United States on death row, have together been described as the death row phenomenon, which is considered by some to be a form of torture.

The proponents of the death penalty point out that that incarceration often produces severe psychological depression which makes the argument for substituting death penalty with life imprisonment moot. A minority among proponents further argue that great suffering is somewhat desirable by the principle of retribution, by its deterrent effect or by other perceived advantages of capital punishment. Occasionally arguments from humaneness are made in favour of capital punishment. The political writer Peter Hitchens has argued that the death penalty is more humane than life imprisonment.

Brutalising effect

The brutalising effect, also know as the brutalization hypothesis, argues that the death penalty has a brutalising or coarsening effect either upon society or those officials and jurors involved in a criminal justice system which imposes it. It is usually argued that this is because it sends out a message that it is acceptable to kill in some circumstances, or due to the societal disregard for the 'sanctity of life'. Some insist that the brutalising effect of the death penalty may even be responsible for increasing the number of murders in jurisdictions in which it is practiced. The theory states that through executions performed by the state, murders performed by individuals are justified under certain circumstances. Individuals often state that their actions should be classed as "justifiable homicide" because, like the state, they feel their action was appropriate.[18]

Discrimination

It is argued that the race of the person to be executed can affect the likelihood that they receive a death sentence. Death-penalty proponents counter this by pointing out that most murders where the killer and victim are of the same race tend to be "crimes of passion" while inter-racial murders are usually "felony murders"; that is, murders which were perpetrated during the commission of some other felony (most commonly either armed robbery or rape). They argue that juries are more likely to impose the death penalty in cases where the offender has killed a total stranger than in those where some deep-seated, personal revenge motive may be present. A recent study showed that just 44% of Black Americans support the death penalty.[19] The opponents of the death penalty also point out that capital punishment has also been used politically to silence dissidents, minority religions and activists. A major example of this is the People's Republic of China from which there are many reports of the death penalty being used for politically motivated ends.[20] Proponents of the death penalty point out that some political prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment or long incarceration die in prison as well. Given that life imprisonment is proposed as substitute for death penalty, the proponents argue, this fact makes analogy irrelevant. They also point out that the debate could easily turn into more equitable application of the death penalty, which may increase the support for death penalty among oppressed minorities. The proponents argue that the problem of racism or political system is falsely attributed to the validity of death penalty itself.

Arguments from democracy

An argument used both in support of and against the death penalty is that one should follow the majority opinion in the country concerned. For example, if a majority of Americans support the death penalty, while in other countries, the public opinion is against, then whatever choice democratic process produce may be considered as the "right" policy for that country. There are two possible objections to this argument. Firstly, voters make up their minds on the basis of ethical arguments offered to them and not the other way round - i.e. ethical arguments should not be decided on the basis of uninformed voting, either for or against death penalty. Secondly, modern democracy is not direct democracy but representative democracy. This means that representatives have difficulty understanding the collective wishes of their constituents, such as whether the votes find life sentences as an acceptable alternative or how much priority they place on the issue of the death penalty itself. No representative can be elected if they base their action in direct opposition to the wishes of the voters.

Law, judiciary and the death penalty

Some argue, from the perspective of a simplified version of legal positivism, that whatever law passed through legislative process is "legal" and moral and ethical debate is rather futile. This leads to a rather consequentialist conclusion that whatever collective consensus achieved through democratic process is "better" if not "just". However, this misses the point of liberal democracy, where certain built-in mechanisms exist to prevent the tyranny of majority.

Critics of the death penalty commonly argue that the death penalty specifically and explicitly violates the right to life clause stated in the most of modern constitutions and human right treaties. It violates sections 3 and 5 of Universal Declaration of Human Rights. While it is not a legally binding document, the declaration served as the foundation for the legally-binding International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which most of countries signed (with some legal reservation). The treaty specifically allows implementation of the death penalty in case of serious crimes or national emergency. Nonetheless, most modern constitutions contain right to life as a fundamental constitutional right, with varying degrees of exemption ranging from explicit exemption of "except in case of serious crime or national emergency" to vague exemption of "without due process" or "except in defence of public interest". Consequently this makes legal debate essentially an a priori argument based on legal text.

Rules of legislative construction

When the constitution does not explicitly exempt the death penalty from the right to life clause, the judiciary are required to interpret the meaning of the clause based on rules of construction. The most common method is plain meaning rule or Golden rule. This is based on strict constructionism or textualism, which dictate that laws are to be interpreted using the ordinary meaning of the language of the statute. In this sense, right to life clauses establish a priori grounds for the prohibition of capital punishment except when it is used as a deterrent to murder. In jurisdictions which practice the death penalty, deterrence is the most common justification cited in the highest court. However, some jurists argue that this may not be the correct legal interpretation, because the plain meaning rule applies only to the extent that they do not produce an absurd or totally obnoxious result, such as removing any a priori justification of punishment. These jurists often advocate social purpose rule, mischief rule or purposive approach which is loosely based on Originalism. Under this criterion, it is possible to go back to the sources outside of legal texts, such as the intention of the law makers or the meaning of the term during the original formation of the concept, which in this case often means 18th to 19th century Europe and America. The proponents of death penalty may claim, citing such sources as Locke, or more appropriately Thomas Jefferson in the case of the US, that the original argument was that people form implicit social contracts, ceding their right to the government to protect natural rights from being abused. Therefore, protection from abuse is the basis of such rights and those who violate such rights automatically forfeit them. Therefore, an a priori case against punishment does not exist. Critics from legal formalism argue that such an approach might cause judges to inadvertently take sides in legislative or political issues which amount to "legislating from the bench", and that the question is for the legislature to address, not the judiciary. On the other hand, advocates of this approach assert that, unlike modern judicial activitism which does not follow precedent, the limit is clearly set in terms of originalism and precedent. Therefore, the approach allows middle ground between possible absurdity of textualism and the danger of judicial activism.

Protection from discrimination, persecution, and cruel and inhumane treatment

The death penalty or a particular sentence of death may still be declared to be in breach of the constitution if it violates equal protection clauses or clauses prohibiting cruel and inhumane treatment. This covers cases where the judicial process is used to prosecute particular minorities, political opponents or individuals. In the US the most commonly cited example is the disproportionate number of racial and economic minorities on death row. In legal terms, mere prevalence of certain minorities in death row or in the general prison population does not amount to the violation of equal protection, because it may simply be a result of these minorities committing more capital crimes. Rather, it must be shown that there is inherent fault in the system, that there was an implicit or explicit policy to persecute minorities or political opponents, or that the jury or judge's decision was shown to be slanted by their prejudice for "individual cases". In the US it is generally considered among jurists that race does not fall into this category except for jury bias which would result in the reversal of conviction. Similarly, incompetent defence by court appointed public defenders is also a valid case for retrial and stay of execution. Similary, killing, pain or psychological fear of killing cannot be a valid argument under the prohibition of cruel and inhumane treatment if the death penalty is declared constitutional. It must be shown that pain is inflicted for the purpose other than execution, such as torture. Then the court can declare that particular method of execution to be unconstitutional, but not the death penalty itself.

Right to fair trial and miscarriage of justice

Most often cited examples of miscarriage of Justice is the US, which probably reflects both the high crime rate as well as the vigorous nature of its judicial process to correct its mistake. Between 1973 and 2005, 122 people in 25 US states were released from death row when their conviction was declared unsafe or clear new evidence of their innocence emerged [12]. Recent progress in forensic science, particularly DNA testing, has brought to light previously unavailable evidence and revealed errors in many old convictions based on circumstancial evidence such as witness testimony [13]. Opponents of the death penalty also point out that certain procedures may be at fault, such as quality of public defender, which "is a better predictor of whether or not someone will be sentenced to death than the facts of the crime"[14]. Most unique to the US is the frequent use of plea bargaining. Because of the large case loads of public prosecutors, it is often commented that the American criminal justice system would cease to function without plea bargaining. In a majority of common law and almost all civil law countries, the prosecutor is not allowed to offer a reduced sentence in exchange of a guility plea or hostile testimony in serious criminal cases. Plea bargains are considered unjust because it is inherent in the process of plea bargaining to induce the innocent to plead guilty, false testimony against the innocent and the overcharge by prosecutors.

In legal terms, advance in forensic sciences, existence of possible miscarriage of justice or some fault in the procedure cannot be an a priori argument for the unconstitutionality of death penalty. Such arguments would lead to the absurd conclusion that the death penalty as well as any form of incareceration is unconstitutional, given that the innocents could be falsely incarcerated or worse, die in prison before being exonerated. However, particular fault in procedure or evidence can be used to overturn individual case of conviction, including a death penalty case. A particular system of judiciary process such as plea bargaining or the system of public defenders can be declared unconstitutional. However, these do not provide legal argument to declare the death penalty as constitutionally invalid.

Deterrence, prevention and the economics of the death penalty

Economics is derived from utilitarianism (from the Latin utilis, useful), which is a dominant approach in social science. It is a theory of ethics (or non ethics) that prescribes the quantitative maximization of good consequences for a population. It is a single value system and a form of consequentialism and moral absolutism. In effect, it asserts that the issue of the death penalty ought to be decided solely on the ground of its cost and benefit to the society rather than on the ground of a priori argument such as right or retribution.

A priori objection

The main objection of utilitarianism is that the approach is almost by definition majoritarian/totalitaian in the sense that, for example, action which saves two lives at the expense of one life is considered "better". This argument is the primary justification for the use of the death penalty against drug trafficking, war or in some instance, extra judicial killing or persecution of political minorities. In the death penalty debate, it is objected to on a priori grounds that it does not even have retributional justification of a specific individual. More specifically, most object to the implication that mistaken execution of innocents is regretable but still justified if the overall effect of the death penalty still saves more lives. Therefore, abandonment of deontological or natural law position is implicit in utilitarian approach. However, the proponents point out a number of advantages. The deontological debate helps to clarify the respective positions of the debate, but offers no way to reach consensus because each argument stands on different a priori ground. Similarly, legal argument can clarify a priori legal or constitutional grounds of the death penalty. However, it offers no insight over whether such law or constitutional clause can be justified on its merit. Utilitarian approach is attractive because it offers a possible way to reach "consensus" among different stances on the subject. (example, see Copenhagen Consensus) For this reason, it is becoming increasingly common in the social sciences, especially in criminology, and the law, especially in law and economics, to use analyses based on the utilitarian (economic) approach. However, it should be stated that the measure of objectivity in humanities are often invariably coloured by a priori ideological affiliation of the participants.

Prevention and Deterrence

Arguably, the most "objective" criterion of analysis is the number of lives being saved or lost as a result of the death penalty. The most specific case under this criterion is incapacitation. That is, the death penalty prevents the perpetrator from committing further murders in the future. Less specific justfication is the deterrent effect. That is, the threat of the death penalty deters potential murders or other serious crimes such as drug trafficking. In the pre-modern period, when authorities had neither the resources nor the inclination to detain criminals indefinitely, the death penalty or other punishments such as caning or hand decapitation were probably the only available means of prevention and deterrent.

Opponents commonly argue that that today's incapacitation or deterrent is equally well served by other means, especially life imprisonment. The proponents, in turn, argue that life imprisonment does not prevent murder within prison and that life imprisonment is less effective deterrent than the death penalty. However, the debate over incapacitation is not intense. Despite the number of murders and other serious crimes within prison, the issue can be dealt simply by removing the dangerous inmates to solitary confinement.

The question of whether or not the death penalty deters murder usually revolves around the statistical analysis. Studies have produced disputed results with disputed significance.[21]. Some studies have shown a correlation between the death penalty and murder rates[22] - in other words, they show that where the death penalty applies, murder rates are also high. This correlation can be interpreted in either that the death penalty increases murder rates by brutalising society (see #Brutalising effect on this page) or that higher murder rates cause the state to retain or reintroduce the death penalty. However, the use of statistics is misleading because statistics show that correlation does not equal causation. In fact, sufficient "proof" from epistemological or scientific grounds amounts to actual demonstration that a deterrent effect took place. This poses a near impossible problem in criminology. The opponent would invariably point to the death row inmate and argue that they are the "proof" that the death penalty does not work as a deterrent. However, the proponent can easily counter by pointing to a far larger number of murderers (many of them repeat offenders) who are serving life imprisonment or long sentences and argue that life imprisonment or long incarceration does not work as a substitute. In fact, this is the result of a sampling problem, where those who do refrain from committing crimes due to detterent effect automatically rule themselves out from the statistics. This means that it is almost impossible to prove the deterrent effect of the death penalty or incarceration by empirical demonstration.

This further invites debate as to which side has the burden of proof. The opponents of the death penalty argue that the burden of proof is on the retentionist to prove that the death peanlty works better than life imprisonment. Given the lack of statistical evidence, therefore, the death penalty ought to be abolished. The proponents argue that, given that existence of a deterrent effect is already acknowledged, the burden of proof is on the abolitionists to prove that the life imprisonment works equally well as a deterrent. Given the lack of statistical evidence that life imprisonment works as equal deterrent, the death penalty ought to be retained.

Appeal to economics

This is not a primary argument for or against the death penalty. The issue was initially raised by the opponents who proposed an anecdotal argument that the death penalty is more expensive and time consuming than life imprisonment. The proponents countered that the death penalty actually has more economic benefit. However, they did not argue that the death penalty should be retained for this reason. Arguments have been produced from both opponents and supporters of the death penalty based on economics.[23] The term "economic" in the context of the death penalty is sometimes used in the wider sense of any utilitarian argument, not merely financial arguments.

Opponents of the death penalty point out that capital cases usually cost more than life imprisonment due to the extra court costs, such as appeals and extra supervisions. Proponents counter this argument by stating that the severity and finality of death as punishment demands that the extra resources be expended. In the US in particular, the accused is allowed to plead guilty so as to avoid the death penalty. This plea requires the accused to forfeit any appeal arguing innocence on material or procedural grounds. Furthermore, by waiving the threat of the death penalty, individuals can be encouraged to plead guilty, accomplices can be encouraged to testify against other defendants, and criminals can be encouraged to lead investigators to the bodies of victims. Proponents of the death penalty, therefore, argue that the death penalty significantly reduces the cost of the judicial process and criminal investigation. Quite a few opponents of the death penalty concede that the economic argument may be in favour of the death penalty, especially in terms of plea baragaining. However, they point out that plea bargaining increases the likelihood of a miscarriage of justice which should be counted as a cost. Moreover, had plea baragaining been abolished, the economic link between the death penalty and life imprisonment would have disappeared. The proponents point out that in such a case, those sentenced to life imprisonment would appeal indefintely, making the cost comparison irrelevant.

Notes

- ↑ Shot at Dawn, campaign for pardons for British and Commonwealth soldiers executed in World War I. Shot at Dawn Pardons Campaign. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ Translated from Waldmann, op.cit., p.147.

- ↑ Schabas, William. The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81491-X.

- ↑ Almost invariably, however, sentences of death for property crimes were commuted to transportation to a penal colony or to a place where the felon was worked as an indentured servant/Michigan State University and Death Penalty Information Center

- ↑ http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGACT500152004

- ↑ Supreme Court bars executing mentally retarded CNN.com Law Center. June 25, 2002.

- ↑ UNICEF, Convention of the Rights of the Child - FAQ: "The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely and rapidly ratified human rights treaty in history. Only two countries, Somalia and the United States, have not ratified this celebrated agreement. Somalia is currently unable to proceed to ratification as it has no recognized government. By signing the Convention, the United States has signaled its intention to ratify. but has yet to do so."

- ↑ ABC News poll, "Capital Punishment, 30 Years On: Support, but Ambivalence as Well" (PDF, July 1, 2006)

- ↑ Papal encyclical, Evangelium Vitae

- ↑ http://www.deathpenaltyreligious.org/education/perspectives/dalailama.html

- ↑ A general overview of the judicial fallibility problem: Amnesty International, "Fatal flaws: innocence and the death penalty in the USA" (November 1998)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Death Penalty Information Center, Innocence and the Death Penalty

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Americal Civil Liberties Union, ACLU resources on capital punishment; Inadequate Representation (October 2003)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Barbara McCuen, "Does DNA Technology Warrant a Death Penalty Moratorium?" (May 2000)

- ↑ Amnesty International, "Singapore - The death penalty: A hidden toll of executions" (January 2004)

- ↑ Amnesty International, "Why Amnesty International opposes the death penalty"

- ↑ American Medical Association, Code of ethics, section E-2.06 Capital punishment

- ↑ Sorensen et al.:"Capital punishment and deterrence: Examining the effect of executions on murder in Texas.", Crime and Delinquency 45, 4: 481-493., 1999.

- ↑ Death Penalty Information Center, Who supports the death penalty? (November 2004)

- ↑ Amnesty International, "Human Rights in China in 2001 - A New Step Backwards" (September 2001)

- ↑ Death Penalty Information Center, Facts about Deterrence and the Death Penalty

- ↑ Joanna M. Shepherd, Capital Punishment and the Deterrence of Crime (Written Testimony for the House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security, April 2004.)

- ↑ Martin Kasten, "An economic analysis of the death penalty" (1996); Michael Coles, "The Cost of Capital Punishment" (August 2002); Phil Porter, "The Economics of Capital Punishment" (1998).

External links

- Country by country list of legal position of Death Penalty from Encarta

- About.com's Pros & Cons of the Death Penalty and Capital Punishment

- 1000+ Death Penalty links all in one place

- U.S. and 50 State DEATH PENALTY / CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LAW and other relevant links from Megalaw

- Updates on the death penalty generally and capital punishment law specifically

- Texas Department of Criminal Justice: list of executed offenders and their last statements

- [10]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Capital_punishment history

- Use_of_capital_punishment_worldwide history

- Capital_punishment_debate history

- List_of_methods_of_capital_punishment history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.