|

|

| (79 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | '''Atheism''', (from [[privative a|privative ''a-'']] + ''theos'' "god") refers to in its broadest sense the absence of [[theism]], the belief in the existence of [[deity|deities]]. The range of the term is broad and encompasses both people who assert that there are no gods, and those who make no claim about whether gods exist or not. Narrower definitions of ''atheism'', however, typically label as atheists only those people who affirmatively assert the nonexistence of gods, and classify other nonbelievers as [[agnosticism|agnostics]] or simply [[nontheism|non-theists]]. Many people who self-identify as atheists do tend to share common [[skepticism|skeptical]] concerns regarding the evidence (or lack of evidence) of the world's many deities and creation stories as well as questioning the goodness and morality of religions that have brought us such things as [[holy wars]] and [[inquisitions]]. Yet while some adhere to philosophies such as [[humanism]], [[naturalism (philosophy)|naturalism]] and [[materialism]], there is no single [[ideology]] that all atheists share, nor does atheism have any institutionalized rituals or behaviors. Indeed, atheism is inspired by many rationales, encompassing personal, [[scientific]], social, philosophical, and historical reasoning. Although atheism is commonly equated with [[irreligion]] in Western culture, some religious beliefs (such as some forms of [[Buddhism]]), though not often so identified by the adherents, have been described as atheistic. | + | {{Copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Ebcompleted}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}} {{Images OK}} |

| | + | '''Atheism''' (from [[Greek language|Greek]]: ''a'' + ''theos'' + ''ismos'' "not believing in god") refers in its broadest sense to a denial of [[theism]] (the belief in the existence of a single deity or deities). Atheism has many shades and types. Some atheists strongly deny the existence of [[God]] (or any form of deity) and attack theistic claims. Yet certainty as to the non-existence of God is as much a belief as is [[religion]] and rests on equally unprovable claims. Just as religious believers range from the ecumenical to the narrow-minded, atheists range from those for whom it is a matter of personal philosophy to those who are militantly hostile to religion. |

| | + | {{readout||right|250px|"Positive" or "strong" atheism is the assertion that no deities exist while "negative" or "weak" atheism is simply the absence of belief in the existence of any deity}} |

| | + | Atheism often buttresses its case on [[science]], yet many modern scientists, far from being atheists, have argued that science is not incompatible with theism. |

| | | | |

| − | ==History==

| + | Some traditional religious belief systems are said to be "atheist" or "non-theist," but this can be misleading. While [[Jainism]] technically can be described as philosophically [[materialism|materialist]] (and even this is subtle vis-à-vis the divine), the claim about [[Buddhism]] being atheistic is more difficult to make. Metaphysical questions put to the [[Buddha]] about whether or not God exists received from him one of his famous "silences." It is inaccurate to deduce from this that the Buddha denied the existence of God. His silence had far more to do with the distracting nature of speculation and dogma than it had to do with the existence or non-existence of God. |

| − | Although the term [[atheism]] originated in [[English language|English]], the term ''atheism'' is the result of the adoption of the [[French language|French]] ''athéisme'' in about 1587, atheistic ideas and beliefs, as well as their political influence, have a more expansive history. In the Far East, a contemplative life not centered on the idea of gods began in the [[6th century B.C.E.]] with the [[Taoism|Taoist]] philosopher [[Lao Zi]] and his contemporary [[Siddhartha Gautama]], founder of [[Buddhism]].

| + | {{toc}} |

| | + | Many people living in the West have the impression that atheism is on the rise around the world, and that the belief in God is being replaced with a more secular-oriented worldview. However, this view is not confirmed. Studies have consistently shown that contrary to popular assumptions, religious membership is actually increasing globally. |

| | | | |

| − | Despite claiming to offer a philosophic and salvific path not centering on deity worship, popular tradition in both religions has long embraced deity worship, the propitiation of spirits, and other elements of folk tradition. Furthermore, Pali Tripitaka, the oldest complete composition of scriptures seem to accept as real the concepts of divine beings, the [[Vedic religion|Vedic]] (and other) gods, rebirth, and heaven and hell. While deities are not seen as necessary to the salvific goal of the early Buddhist tradition, their reality is not questioned.

| + | ==The Rationale of Atheism== |

| | + | Atheism is a belief that is held for a variety of reasons. |

| | | | |

| − | Supernatural elements of the Buddhist tradition as later additions are generally accepted by modern philology. In fact, such view appeared as early as 18th century in Japan among scholars from Kaitokudou School (懐徳堂) which advocated version of atheism and made claim that supernatural element in ancient text of Buddhism, Shintoism, Taoism and Confusiasm are fictitious exaggeration. Nakamoto Tominaga (富永仲基, 1715-1746) concluded that, among vast amount of [[Mahayana]] Buddhist scriptures, only part of Agama sutra is actual words of Siddhartha Gautama. General thrust of his argument are now supported by modern sholarship which has identified [[Dhammapada]], the last two chapter of [[Sutta Nipata]] in Pali Tripitaka and corresponding part of Agama Sutra in Sanskrit Tripitaka as well as addition of few fragments in other scriptures to be the oldest composition. This view, often described as Daijyou Hibutu Setu (大乗非仏説-Mahayana Non Buddhism Theory) has been ongoing controversy in Japanese Buddhism.

| + | ===Logical reasons=== |

| | + | Some atheists base their stance on philosophical grounds, arguing that their position is based on [[logic]]al rejection of theistic claims. Indeed, many atheists claim that their view is merely the absence of a certain belief, suggesting that the burden of proving God's existence is upon theists. In this line of thought, it follows that if theism's arguments can be refuted, non-theism becomes the default position. Many atheists have argued for centuries against the most popular "proofs" of God's existence, noting problems in the theist lines of reasoning. Atheists who attack specific forms of theism often claim it as being self-contradictory. One of the most common arguments against the existence of the Christian God is the [[problem of evil]], which Christian apologist [[William Lane Craig]] has referred to as "atheism's killer argument." This line of reasoning claims that the presence of [[evil]] in the world is logically inconsistent with the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent God. Instead, atheists claim it is more coherent to conclude that God does not exist than to believe that He/She does exist but readily allows the promulgation of evil. |

| | | | |

| − | The thoroughly materialistic and anti-religious philosophical [[Carvaka]] school that originated in [[India]] around 6th century B.C.E. is probably the most explictly atheist school of philosophy in the region. It was advocated by [[Ajita Kesakambalin]], whose saying is recorded in Pali scriptures by the Buddhists he was debating. <ref>{{cite web

| + | A form of atheism known as "ignosticism," asserts that the question of whether or not deities exist is inherently meaningless. It is a popular view among many [[logical positivism|logical positivists]] such as [[Rudolf Carnap]] and [[A. J. Ayer]], who claim that talk of gods is literally nonsensical. For them, theological statements (such as those affirming god's existence) cannot have any truth value, since they lack [[falsifiability]]. This refers to the fact that claims of transcendence and of metaphysical properties cannot be tested by empirical means and must therefore be rejected as null hypotheses. In ''Language, Truth and Logic'', Ayer stated that theism, atheism and [[agnosticism]] were equally meaningless terms, insofar as they treat the question of the existence of God as a real question. However, despite Ayer's criticism of atheism as a concept (perhaps using the definition typically associated with [[strong atheism]]), ignosticism is still considered as a form of atheism in most classifications of religious thought. |

| − | |url=http://www.tamu.edu/chr/agora/sukumaran3.html

| |

| − | |title=Elements of Atheism in Hindu Thought

| |

| − | |publisher=AGORA

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-06-26

| |

| − | }}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | :"When this was said, Ajita Kesakambalin said to me, 'Great king, there is nothing given, nothing offered, nothing sacrificed. There is no fruit or result of good or bad actions. There is no this world, no next world, no mother, no father, no spontaneously reborn beings; no priests or contemplatives who, faring rightly and practicing rightly, proclaim this world and the next after having directly known and realized it for themselves. A person is a composite of four primary elements. At death, the earth (in the body) returns to and merges with the (external) earth-substance. The fire returns to and merges with the external fire-substance. The liquid returns to and merges with the external liquid-substance. The wind returns to and merges with the external wind-substance. The sense-faculties scatter into space. Four men, with the bier as the fifth, carry the corpse. Its eulogies are sounded only as far as the charnel ground. The bones turn pigeon-colored. The offerings end in ashes. Generosity is taught by idiots. The words of those who speak of existence after death are false, empty chatter. With the break-up of the body, the wise and the foolish alike are annihilated, destroyed. They do not exist after death.'

| + | ===Scientific reasons=== |

| − | | + | As a further development of the rationalist position, many feel that theories of divine creation blatantly conflict with modern science, especially [[evolution]]. For some atheists, this conflict is reason enough to reject theism. Evolutionary science, supported by a large body of [[Paleontology|paleontological]] and [[Genomics|genomic]] evidence and accepted by the overwhelming majority of biologists, describes how complex life has developed through a slow process of random [[mutation]] and [[natural selection]]. It is now known that humans share 98 percent of our genetic code with [[chimpanzee]]s, 90 percent with [[mouse|mice]], 21 percent with [[roundworm]]s, and seven percent with the bacterium [[E. coli]]. This humbling perspective is quite different from that of most theistic traditions, such as the [[Abrahamic religion]]s, in which humans are thought to be created "in God's image" and are existentially distinguished from the other "beasts of the Earth." Similarly, astronomical facts, such as the recognition of Earth's [[Sun]] as only one undistinguished star among billions in the [[Milky Way]], are seen by some atheists as rendering implausible the proposition that this universe was created with mankind in mind. Finally, some atheists argue that religion emerged as a pseudo-scientific explanation for natural phenomena and that, with the progress of human scientific endeavor, these etiological myths have been rendered unnecessary. |

| − | ===Classical Greece and Rome=== | |

| − | [[image:socrates.png|thumb|150px|right|Socrates]]

| |

| − | In western [[Classical Antiquity]], theism was the fundamental belief that supported the divine right of the State. Historically, any person who did not believe in any deity supported by the State was fair game to accusations of atheism, a [[Capital punishment|capital crime]]. For political reasons, [[Socrates]] in [[Athens]] ([[399 B.C.E.]]) was accused of being 'atheos' ("refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). Despite the charges, he claimed inspiration from a divine voice and on his deathbed he asked that a [[rooster]] be sacrificed to the god [[Asclepius]]. Christians in [[Rome]] were also considered subversive to the state religion and prosecuted as atheists. Thus, charges of atheism, meaning the subversion of religion, were often used similarly to charges of [[heresy]] and [[impiety]] — as a political tool to eliminate diversity in religion.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The oldest known expressions of atheism as we now understand it are attributed to [[Epicurus]] around [[300 B.C.E.]]. The aim of the [[Epicurean]]s was mainly to attain peace of mind by exposing fear of divine wrath as irrational. One of the most eloquent expression of Epicurean thought is [[Lucretius]]' ''[[On the Nature of Things]]'' ([[1st century B.C.E.]]). Lucretius was not an atheist as he did believe in the existence of gods, and Epicurus was ambiguous on this topic too. However both of them certainly thought that if gods existed they were uninterested in human existence. Both of them also denied the existence of an afterlife. Perhaps they are better described as [[materialists]] than atheists. Epicureans were not persecuted, but their teachings were controversial, and were harshly attacked by the mainstream schools of [[Stoicism]] and [[Neoplatonism]]. The movement remained marginal, and gradually died out at the end of the [[Roman Empire]], until it was revived by [[Pierre Gassendi]] in the [[17th century]]. During the late [[Roman Empire]], atheism — a [[Capital punishment|capital crime]] — was a common legal prosecution against Christians by [[Henotheism|henotheists]]. Christians rejected the Roman gods, and henotheists rejected the exclusivity of Christian [[monotheism]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===The Middle Ages===

| |

| − | In the [[Europe|European]] [[Middle Ages]] people were persecuted for [[heresy]], especially in countries where the [[Inquisition]] was active. Medieval ''impiety'' and ''godlessness'' were closer to weak atheism than avowed strong atheism (see below), and hardly any expression of strong atheism is known from this period. The term 'Epicurean' was essentially a slur and had no active proponents. [[Saint Anselm]]'s [[ontological argument]] at least seems to acknowledge the validity of the question about god's existence. [[Pope Boniface VIII]], while emphatically insisting on the political supremacy of the church, held some clearly atheist positions, like "The Christian religion is a human invention like the faith of the Jews and the Arabs" or

| |

| − | "The dead will rise just as little as my horse which died yesterday".

| |

| − | Medieval beliefs that most closely approach strong atheism were probably held by some members of the [[pantheism|pantheistic]] [[Brethren of the Free Spirit]]. A man called Löffler, who was burned in [[Bern]] in [[1375]] for confessing adherence to this movement, is reported to have taunted his executioners that they would not have enough wood to burn "Chance, which rules the world". Contemporaneously, in [[India]] the [[Carvaka]] school of philosophy, which continued until the fourteenth century, was openly atheistic and [[empirical]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===The Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Age of Enlightenment===

| |

| − | During the time of the [[Renaissance]] and the [[Reformation]], criticism of the religious establishment started to become more frequent, but did not amount to actual atheism. The dissidents also turned against each other: [[John Calvin]] narrowly escaped being burned by [[Lutheran]]s in [[1532]], and himself approved of the burning of the [[Unitarian]] Christian [[Michael Servetus]] in [[1553]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | The term ''athéisme'' itself was coined in France in the 16th century, and was initially used as an accusation against scientists, critics of religion, materialistic philosophers, [[deism|deists]], and others who seemed to represent a threat to established beliefs. The charge was almost invariably denied. Thus, the concept of atheism re-emerged initially as a reaction to the intellectual and religious turmoil of the [[Age of Enlightenment]] and the [[Reformation]] — as a charge used by those who saw the denial of god and godlessness in the controversial positions being put forward by others. How dangerous it was to be accused of being an atheist at this time is illustrated by the fact that in [[1766]], the French nobleman [[Jean-François de la Barre]], was [[torture]]d, beheaded, and his body burned for alleged [[vandalism]] of a [[crucifix]], a case that became celebrated because [[Voltaire]] tried unsuccessfully to have the sentence reversed.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Among those accused of atheism was [[Denis Diderot]] ([[1713]]–[[1784]]), one of the Enlightenment's most prominent ''philosophes'', and editor-in-chief of the [[Encyclopédie]], which sought to challenge religious, particularly [[Catholicism|Catholic]], dogma: "Reason is to the estimation of the ''philosophe'' what grace is to the Christian", he wrote. "Grace determines the Christian's action; reason the ''philosophe's''". [http://www.pinzler.com/ushistory/diderotsupp.html] Diderot was briefly imprisoned for his writing, some of which was banned and burned.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The English materialist philosopher [[Thomas Hobbes]] ([[1588]]–[[1679]]) was also accused of atheism, but he denied it. His theism was unusual, in that he held god to be material. Even earlier, the British playwright and poet, [[Christopher Marlowe]] ([[1563]]–[[1593]]), was accused of atheism when a tract denying the divinity of Christ was found in his home. Before he could finish defending himself against the charge, Marlowe was murdered, although this was not related to the religious issue.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===The Modern Period===

| |

| − | By the [[1770s]], atheism was ceasing to be a dangerous accusation that required denial, and was evolving into a position openly avowed by some. The first open denial of the existence of god and avowal of atheism since classical times may be that of [[Baron d'Holbach|Paul Baron d'Holbach]] ([[1723]]–[[1789]]) in his [[1770]] work, [[The System of Nature]]. D'Holbach was a Parisian social figure who conducted a famous salon widely attended by many intellectual notables of the day, including Diderot, [[Jean Jacques Rousseau]], [[David Hume]], [[Adam Smith]], and [[Benjamin Franklin]]. Nevertheless, his book was published under a pseudonym, and was banned and publicly burned by the [[Executioner]]. <!-- Who was the "Executioner"? —>

| |

| | | | |

| − | The pamphlet ''Answer to [[Joseph Priestley|Dr Priestley]]'s Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever'' ([[1782]]) is considered to be the first published declaration of atheism in Britain - plausibly the first in English (as distinct from covert or cryptically atheist works). The otherwise unknown 'William Hammon' (possibly a pseudonym) signed the preface and postscript as editor of the work, and the anonymous main text is attributed to [[Matthew Turner]] (d. [[1788]]?), a Liverpool physician who may have known Priestley. Historian of atheism David Berman has argued strongly for Turner's authorship, but also suggested that there may have been two authors (see Berman 1988, Chapter 5).

| + | All this said, it is also true that there are many scientists, [[Isaac Newton|Newton]] and [[Albert Einstein|Einstein]] among them, who do not believe that science is incompatible with the existence of God. [[Charles Darwin|Darwinian]] evolution, for example, can be understood as a method God developed for the propagation of life. |

| | | | |

| − | Afterward, the [[French Revolution]] of [[1789]] catapulted atheistic thought into political notability, and opened the way for the [[19th century]] movements of [[Rationalism]], [[Freethought]], and [[Liberalism]]. An early atheistic influence in Germany was ''The Essence of Christianity'' by [[Ludwig Feuerbach]] ([[1804]]–[[1872]]). He influenced other German 19th century atheistic thinkers like [[Karl Marx]], [[Arthur Schopenhauer]] ([[1788]]–[[1860]]) and [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] ([[1844]]–[[1900]]).

| + | ===Personal and Practical reasons=== |

| − | [[Image:Kmarx.jpg|thumb|100px|left|Karl Marx]]

| + | In addition to using philosophical arguments, there are those atheists who cite social, psychological, and practical reasons for their beliefs. Many people are atheists not as a result of philosophical deliberation, but rather because of the means by which they were brought up or educated. Some people are atheists at least partly because of growing up in an environment where atheism is relatively common, such as those who are raised by atheist parents. Some people are led to atheism by unpleasant experiences with their inherited traditions. |

| − | The freethinker [[Charles Bradlaugh]] (1833–1891) was repeatedly elected to the [[British Parliament]], but was not allowed to take his seat after his request to affirm rather than take the religious oath was turned down (he offered to take the oath, but this too was denied him). After Bradlaugh was re-elected for the fourth time, a new Speaker allowed Bradlaugh to take the oath and permitted no objections: he became the first outspoken atheist to sit in Parliament, where he participated in amending the [[Oaths Act]]. In many countries, denying god was included as a crime of [[blasphemy]]. In several countries, such as [[Germany]], [[Spain]], and the [[United Kingdom]], these laws remain. Likewise, some American states, such as [[Massachusetts]], retain such laws; however, these laws are rarely enforced, if at all.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In [[1844]], [[Karl Marx]] ([[1818]]–[[1883]]), an atheistic political economist, wrote in his ''Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right'':

| + | Some atheists claim that their beliefs have positive practical effects on their lives. For instance, atheism may allow one to open their mind to a wide variety of perspectives and worldviews since they are not committed to [[Dogma|dogmatic]] beliefs. However, since rigidly-held atheism may be a dogmatic belief, those with an open mind are more likely to be [[agnosticism|agnostics]]. Such atheists may hold that searching for explanations through natural science can be more beneficial than searching through faith, the latter of which often draws irreconcilable dividing lines between individuals with different beliefs. |

| − | [[Image:Nietzsche1882.jpg|thumb|100px|right|Friedrich Nietzsche]] | |

| − | :"Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the [[opium of the people]]. [http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm]

| |

| | | | |

| − | Marx believed that people turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations; that is, Marx suggests religion is an attempt at transcending the material state of affairs in a society — the pain of class oppression — by effectively creating a dream world, rendering the religious believer amenable to [[social control]] and exploitation in this world while they hope for relief and justice in [[life after death]]. In the same essay, Marx states, "...[m]an creates religion, religion does not create man..."

| + | ==Typology of atheism== |

| | + | The first attempts to define or develop a typology annotating the varieties of atheism occurred in religious [[apologetics]], which typically depicted atheism as a licentious belief system. Regardless, a diversity of atheist opinion has been recognized at least since [[Plato]], and common distinctions have been established between ''practical atheism'' and ''contemplative'' or ''speculative atheism''. Practical atheism was said to be caused by moral failure, hypocrisy, or willful ignorance. Atheists in the practical sense were those who behaved as though God, morals, ethics and social responsibility did not exist. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Friedrich Nietzsche]], a prominent 19th century philosopher, is well-known for coining the aphorism ''"[[God is dead]]" ''([[German language|German]]: "''Gott ist tot''"); incidentally the phrase was not spoken by Nietzsche directly, but was used as a dialogue for the characters in his works. Nietzsche argued that Christian theism as a belief system had been a moral foundation of the Western world, and that the rejection and collapse of this foundation as a result of modern thinking (the ''death of God'') would naturally cause a rise in [[nihilism]] or the lack of values. While Nietzsche was staunchly atheist, he was also concerned about the negative effects of nihilism on humanity. As such, he called for a re-evaluation of old values and a creation of new ones, hoping that in doing so man would achieve a higher state he labeled the [[Übermensch|Overman]]. | + | On the other hand, speculative atheism, which involves philosophical contemplation of the nonexistence of god(s), was often denied by theists throughout history. That anyone might ''reason'' their way to atheism was thought to be impossible. Thus, speculative atheism was collapsed into a form of practical atheism, or conceptualized as a hateful fight against God. These negative connotations are one of the reasons for the (continued) popularity of euphemistic alternative terms for atheists, like [[secularism|secularist]], [[empiricism|empiricist]], and [[agnosticism|agnostic]]. These connotations likely arise from attempts at suppression and from historical associations with practical atheism. Indeed, the term ''godless'' is still used as an abusive epithet. Thinkers such as J. C. A. Gaskin have abandoned the term ''atheism'' in favor of ''unbelief'', citing the fact that both the derogatory associations of the term and its vagueness in the public eye have rendered atheism an undesirable label. Despite these considerations, for others ''atheist'' has always been the preferred title, and several types of atheism have been identified by writers. |

| | | | |

| − | ===The 20th Century===

| |

| − | State support of atheism and opposition to organized religion was made policy in all [[communist state]]s, including the [[People's Republic of China]] [http://www.tibet.ca/wtnarchive/1999/1/21_1.html] and the former [[Soviet Union]]. In theory and in practice these states were secular. The justifications given for the social and political sidelining of religious organizations addressed, on one hand, the "irrationality" of religious belief, and on the other the "parasitical" nature of the relationship between the church and the population. Churches were tolerated, but were subject to strict control - in that church officials had to be vetted by the state and attendance of church functions could endanger one's career. Consequently, religious organizations, such as the [[Catholic Church]], were among the most stringent opponents of communist regimes. However, the initial strict measures of control over religious activity were gradually relaxed in most communist states. In an extreme example, [[Albania]] under [[Enver Hoxha]] became, in [[1967]], the first (and to date only) formally declared atheist state. Hoxha went far beyond what any other country had attempted and completely prohibited religious observance, systematically repressing and persecuting adherents. The right to religious practice was restored in [[1990]].

| |

| − |

| |

| − | During the [[Cold War]], the [[United States]] often characterized its opponents as "Godless Communists"[http://www3.niu.edu/univ_press/books/257-5.htm], which tended to reinforce the view that atheists were unreliable and unpatriotic (an example of the [[fallacy]] known as [[affirming the consequent]]). In the [[1988]] U.S. presidential campaign, Republican presidential candidate [[George H. W. Bush]] said, "I don't know that atheists should be regarded as citizens, nor should they be regarded as patriotic. This is one nation under God." [http://www.robsherman.com/information/liberalnews/2002/0303.htm]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Although the actual term ''atheism'' originated in 16th Century [[France]], ideas that would be recognized as atheistic today existed even before [[Classical Antiquity]]. [[Epicurus]] proposed theories that can be classified as atheistic, such as a lack of belief in an afterlife, though he remained ambiguous concerning the actual existence of deities. Before him, [[Socrates]] was [[Trial of Socrates|sentenced to death]] partly on the grounds that he was an atheist, although he did express belief in several forms of divinity, as recorded in [[Plato]]'s ''[[Apology (Plato)|Apology]]''. This criminal connotation attached to atheistic ideas ([[heresy]]) would remain, at varying levels of severity, until [[the Renaissance]], when criticism of the Church became more prevalent and tolerated.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Atheism disappeared from the philosophy of the [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] and [[Roman Empire|Roman]] traditions as [[Christianity]] gained influence. During the [[Age of Enlightenment]], the concept of atheism re-emerged as an accusation against those who questioned the religious [[status quo]], but by the late 18th century it had become the philosophical position of a growing minority. By the 20th century, along with the spread of [[rationalism]] and [[secular humanism]], atheism had become common, particularly among [[scientist]]s (see [[#International survey of contemporary atheism|international survey of contemporary atheism]]). In the 20th century, atheism also became a staple of the various [[Communist state]]s, helping to enforce some of the negative connotations of atheism in places where anti-communism was widespread - especially in the [[United States]], where the term became synonymous with being unpatriotic during the [[Cold War]] in a similar, but less extreme form, as it had in [[Nazi Germany]] under [[Adolf Hitler]].

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==Reasons for atheism==

| |

| − | ===Philosophical and logical reasons===

| |

| − | Some atheists base their stance on rational or philosophical grounds, arguing that their position is based on logical analysis, and subsequent rejection, of theistic claims. These [[existence of God#Arguments against the existence of God|arguments against the existence of deities]] consist of a number of different problems with theism. Chief among these problems is absence of evidences supporting theistic claims. Also, instead of simplification of explanation (of how nature works) theism tremendously complicates it by introducing new questions like origin of god(s), their dwelling, style of life, exercising their powers, conflicts with laws of physics, unpredictability, etc.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Many atheists hold that as their view is merely the absence of a certain belief, the only defense that atheism needs is a good offense. If theism's arguments are refuted, nontheism, as the only alternative, becomes the default position. As such, many atheists have argued against the most famous "proofs" of God's existence for centuries. Whether all of the theistic arguments have been refuted is a matter in dispute.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Philosophical atheists assert various reasons for their position, most grounded in the conviction that the nonexistence of deities (in general or specific) is rationally better supported. They state the onus is on theists to prove the existence of god(s), rather than on atheists to disprove the existence of any supposed deities. Since the theistic conception of god is such a complex notion, the atheist claims that the burden of proof is upon the theist to prove such an unlikely phenomena, rather than on them to deny it. If there is indeed a god, the believer needs to present the evidence for this phenomena which is otherwise anomolous with what is experienced in the physical world. The theist must show that there are spiritual facts that must be found beyond the world of common experience, and atheists assert such facts have not been provided.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | There are also many atheists who attack specific forms of theism as being self-contradictory. One of the most common arguments against the existence of a specific God is the [[problem of evil]]. Christian apologist [[William Lane Craig]] has referred to this problem as "atheism's killer argument". This argument claims that the existence of evil in the world contradicts the existence of a benevolent God. Instead, it is more coherent to conclude that God does not exist rather than believing that he does exist but does nothing to halt the promulgation of evil.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ===Scientific reasons===

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Many feel that the teaching that humankind and the universe were created by one or more deities is in blatant conflict with modern science, especially [[evolution]]. For some atheists this conflict is reason enough to reject theism. In contrast, some theists draw the opposite conclusion from the same conflict, and reject evolution in favor of [[Creation-evolution controversy|creationism]], despite the essentially complete consensus about evolution among scientists. Other theists accept that evolution happened and do not believe that there is a conflict. Evolutionary science, supported by a large body of [[Paleontology|paleontological]] and [[Genomics|genomic]] evidence and accepted by the overwhelming majority of biologists, describes how complex life has developed through a slow process of random [[mutation]] and [[natural selection]], and that the human race is merely one species among others, one of many random products of this [[stochastic]] process. It is now known that humans share 98% of our genetic code with chimpanzees, 90% with mice, 21% with roundworms, and 7% with the bacterium [[E. coli]]. This humbling perspective is quite different from that of most theistic religions, which give humans a unique and central status; in the [[Abrahamic]] religions, for instance, humans are thought to be created "in God's image" and to be a qualitatively different thing from the "beasts of the Earth". Similarly, the facts that Earth's Sun is only one undistinguished star among billions in the [[Milky Way]], which itself is merely one undistinguished galaxy among billions of others, and that modern humans have existed at all for only 0.0015% of the [[age of the universe]], are seen by some atheists as rendering implausible the proposition that this universe was created (by some deity) with mankind in mind.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Furthermore, it has been put forth that religions in the past used supernatural entities and forces to provide explanations for physical phenomenon which were, at that time, beyond their grasp. In [[Ancient Greece]], for instance, numerous gods had dominion over natural phenomena, such as [[Helios]] the god of the sun, [[Zeus]] the god of thunder, and [[Poseidon]] the god of earthquakes and the sea. Any processes observed within these phenomena were explained through mythical stories involving the god. Such deities have been playfully labelled [[Gods of the gaps]]. Some atheists claim, however, that with the progress of human scientific endeavour and the subsequent explanation of natural phenomena by way of the [[scientific method]], these gods of creation and explanation have been rendered unneccessary. Although this may leave room for a [[deist|deistic]] God who sets in place unchanging natural laws, such arguments as [[Hume's dictum]] and [[Occam's razor]] leave little room for a being even of this type. While the success of modern science and engineering in the absence of divine intervention could still be interpreted to imply that deities take a rather hands-off approach to the world, many atheists feel that the simplest explanation is that there are indeed no deities.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ===Personal and social reasons===

| |

| − | As well as atheists with philosophical reasons, there are explicit atheists who cite social, psychological, practical, and other reasons for their beliefs. Some people are atheists at least partly because of growing up in an environment where atheism is relatively common, such as being raised by atheist parents. Many people are atheists not as a result of philosophical deliberation, but rather because of the way they were brought up or educated. Also, they may simply adopt the predominant beliefs of the culture in which they grew up. Most atheists contend that the same is true even for many theistic believers. For instance, most people who grow up in a predominantly Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, or Christian community or culture are most likely to adopt the prevalent religion of that given locale.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Practical reasons for atheism include reasons why accepting atheism over theism produces positive overall effects on a person's life. That is, atheism often allows one to open their mind to a wide variety of perspectives and worldviews since they are not committed to dogmatic beliefs. Some people hold atheistic beliefs on the grounds that it is conducive towards living a better life, such as the belief that atheism is more ethical or useful than theism. Such atheists may hold that searching for explanations through natural science is more beneficial than doing it through faith, the latter of which often draws irreconcilable dividing lines between individuals with different beliefs as often as it unites. Closely related are moral reasons for atheism, which include cases where the requirement to do what is right favors being an atheist, or at the very least, not supporting certain sects or practices of theism. Those who cannot accept the notion of an evil god are forced to conclude that any immoral religion is necessarily false. Arguments that theism promotes immorality often center around the contention that a great deal of violence, including [[religious war|war]], has been brought about by religious beliefs and practices. In fact, the toll upon humanity witnessed in the ultraviolent Thirty Years War (which spanned 1618 and 1648) between Protestants and Catholics, actually created a large amount of discontent with religious dogmatism. This, in combination with the Enlightenment focus upon rational classification in the following century, helped to create the impetus for understanding the various forms of religious belief. With all things considered, many thinkers began to construe [[deism]] or else atheism as the most rational forms of religious belief.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | Christian psychologist Paul Vitz (1999) argues that numerous individuals have psychological reasons for aligning themselves with atheism. That is, certain neurotic personality characteristics create psychological barriers to the act of believing in God, according to Vitz. However, such an assertion construes atheism as some kind of malady in the non-believer, marking Vitz's Christian bias. It is important to note that emotion and "feelings" play an important role not only for atheists, but also for theists, as well. However, an understanding of the psychological origins for belief in a god may contribute to some atheists' lack of religious belief.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | ==Types and typologies of atheism==

| |

| | ===Weak and strong atheism=== | | ===Weak and strong atheism=== |

| − | The broadest definition of atheism is found in the dichotomy of weak and strong atheism. ''[[Weak atheism]]'', sometimes called ''soft atheism'', ''negative atheism'' or ''neutral atheism'', is the absence of belief in the existence of [[deity|deities]] without the positive assertion that deities do not exist. ''[[Strong atheism]]'', also known as ''hard atheism'' or ''positive atheism'', is the assertion that no deities exist. While the terms ''weak'' and ''strong'' are relatively recent, the concepts they represent have been in use for some time. In earlier philosophical publications, the terms ''negative atheism'' and ''positive atheism'' were more common, most notbaly used by [[Antony Flew]] in 1972, although [[Jacques Maritain]] (1953, Chapter 8, p.104) used the phrases in a similar, but strictly Catholic apologist, context as early as 1949. Although explicit atheists (see below) who consciously reject theism), may subscribe to either ''weak'' or ''strong'' atheism, weak atheism also includes implicit atheists, that is, nontheists who have not consciously rejected theism, but lack theistic belief, arguably including such uninformed persons as infants.

| + | Some writers distinguish between weak and strong atheism. “Weak atheism,” sometimes called “soft atheism,” “negative atheism” or “neutral atheism,” is the absence of belief in the existence of [[deity|deities]] without the positive assertion that deities do not exist. In this sense, weak atheism may be considered a form of [[agnosticism]]. These atheists may have no opinion regarding the existence of deities, either because of a lack of interest in the matter (a viewpoint referred to as [[apatheism]]), or a belief that the arguments and evidence provided by both theists and strong atheists are equally unpersuasive. Specifically, they argue that theism and strong atheism are equally untenable, on the grounds that asserting or denying the existence of deities requires a faith-claim. |

| | | | |

| − | Theists claim that a single deity or group of deities exists. Weak atheists do not assert the contrary; instead, they only refrain from assenting to theistic claims. In this sense, weak atheism may be considered a form of [[agnosticism]]. Some weak atheists are without any opinion regarding the existence of deities, either because of a lack of thought on the matter, a lack of interest in the matter (see [[apatheism]]), or a belief that the arguments and evidence provided by both theists and strong atheists are equally unpersuasive. Others may doubt or dispute claims for the existence of deities, while not actively asserting that deities do not exist, a position commonly classified as explicit weak atheism. Similarly, some weak atheists feel that theism and strong atheism are equally untenable, on the grounds that faith is required both to assert and to deny the existence of deities. As such, they conclude that both theism and strong atheism have inherited the burden of proof as to whether or not a god does or doesn't exist, respectively. Some also base their belief on the notion that it is impossible to [[Negative proof|prove a negative]], in this case, the fact that god does ''not'' exist. While a weak atheist might consider the nonexistence of deities likely on the basis that there is insufficient evidence to justify belief in a deity's existence, a strong atheist has the additional view that positive statements of nonexistence are merited when evidence or arguments indicate that a deity's nonexistence is certain or probable. Strong atheism may be based on arguments that the concept of a deity is self-contradictory and therefore impossible (positive [[ignosticism]]), or that one or more of the properties attributed to a deity are incompatible with what we observe in the world. Examples of this may be found in quantum physics, where the existence of mutually exclusive data negates the possibility of omniscience, usually a core attribute of monotheistic conceptions of deity.

| + | On the other hand, “strong atheism,” also known as “hard atheism” or “positive atheism,” is the positive assertion that no deities exist. Many strong atheists have the additional view that positive statements of nonexistence are merited when evidence or arguments indicate that a deity's nonexistence is certain or probable. Strong atheism may be based on arguments that the concept of a deity is self-contradictory and therefore impossible (positive [[ignosticism]]), or that one or more attributes of a deity are incompatible with worldly realities. |

| | | | |

| | ===Implicit and explicit atheism=== | | ===Implicit and explicit atheism=== |

| − | The second tradition understands atheism more narrowly, construing it as the conscious rejection of theism, and does not consider mere absence of theistic belief or suspension of judgment concerning theism to be forms of atheism. Under this conceptualization of atheism, conscious rejection of theism is the key. These terms were coined by George H. Smith (1979, p.13-18). Implicit atheism is defined by Smith as the lack of theistic belief without conscious rejection of it. This rejection, according to Smith, is not actually regarded as atheistic at all, and the umbrella term [[nontheism]] is typically used in its place. Explicit atheism, meanwhile, is defined by a conscious rejection of theistic belief, and is sometimes called ''antitheism'' (see below).

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [[Image:Atheismimplicitexplicit2.PNG|thumb|230px|A chart showing the relationship between the weak/strong (positive/negative) and implicit/explicit dichotomies. Strong atheism is always explicit, and implicit atheism is always weak.]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | For Smith, explicit atheism is subdivided further according to whether or not the rejection of theism is based upon rational grounds. The term ''critical atheism'' is used to label the view that belief in god is irrational, and is itself subdivided into a) the view usually expressed by the statement "I do not believe in the existence of a god or supernatural being"; b) the view usually expressed by the statement, "god does not exist" or "the existence of god is impossible"; and c) the view which "refuses to discuss the existence or nonexistence of a god" because "the concept of a god is unintelligible" (p.17).

| + | The terms implicit and explicit atheism were coined by George H. Smith in 1979 for purposes of understanding atheism more narrowly. Implicit atheism is defined by Smith as the lack of theistic belief without conscious rejection of it. Explicit atheism, meanwhile, is defined by a conscious rejection of theistic belief and is sometimes called "''antitheism''." |

| | | | |

| − | Although Nagel rejects Smith's definition of atheism as merely "lack of theism", acknowledging only explicit "atheism" as true atheism, his tripartite classification of ''rejectionist atheism'' (commonly found in the philosophical literature) is identical to Smith's ''critical atheism'' typology. The difference between Nagel on the one hand and Smith]s on the other has been attributed to the different concerns of professional philosophers and layman proponents of atheism. Everitt (2004) makes the point that professional philosophers are more interested in the epistemological grounds for giving or withholding assent to propositions (including the existence of God) while laypersons are presumably more concerned with social reasons. So, in philosophy, atheism is commonly defined along the lines of "rejection of theistic belief", rendering Smith's the best ''philosophical'' definition of atheism. This is often misunderstood to mean only the view that there is no God, but it is conventional to distinguish between two or three main sub-types of atheism in this sense. As it happens, Smith's definition of explicit atheism is that most common among laypeople. Here, atheism is defined in the strongest possible terms, as the belief that there is no god. Thus, most laypeople would not recognize mere absence of belief in deities (implicit atheism) as a type of atheism at all, and would tend to use other terms, such as "skeptic" or "agnostic" or "non-atheistic nontheism", for this position. Such usage is not exclusive to laypeople, however: atheist philosopher Theodore Drange uses the narrow definition.

| + | As it happens, Smith's definition of explicit atheism is also the most common among laypeople. For laypersons, atheism is defined in the strongest possible terms, as the belief that there is no god. Thus, most laypeople would not recognize mere absence of belief in deities (implicit atheism) as a type of atheism at all, and would tend to use other terms, such as [[skepticism]] or [[agnosticism]]. Such usage is not exclusive to laypeople, however, as many atheist philosophers, including Theodore Drange, use the narrow definition. |

| | | | |

| − | The aforementioned terms ''weak atheism'' and ''strong atheism'' (or ''negative atheism'' and ''positive atheism'') are often used as synonyms of Smith's less-well-known ''implicit'' and ''explicit'' categories. However, the original and technical meanings of implicit and explicit atheism are quite different and distinct from weak and strong atheism, having to do with conscious rejection and unconscious rejection of theism rather than with positive belief and negative belief.

| + | ===Antitheism=== |

| − | | + | ''Antitheism'' typically refers to a direct opposition to [[theism]]. In this sense, it is a form of critical strong atheism. While in other senses atheism merely denies the existence of deities, antitheists may go so far as to believe that theism is actually harmful for human beings. As well, they may simply be atheists who have little tolerance for theistic views, which they perceive to be [[irrationality|irrational]]/dangerous. However, ''antitheism'' is also sometimes used, particularly in religious contexts, to refer to opposition to [[God]] or [[divine]] things, rather than an opposition to the belief in God. Using the latter definition, it is possible to be an antitheist without being an atheist or nontheist. |

| − | ===Atheism as absence of theism=== | |

| − | Among modern atheists, the view that atheism means "without theistic beliefs" has a great deal of currency. This very broad definition is justified by reference to etymology as well as consistent usage of the word by atheists. Although this definition of atheism is frequently disputed, it is not a recent invention; this use has a history spanning over 230 years. Two atheist writers who are clear in defining atheism so broadly that uninformed children are counted as atheists are d'Holbach (1772) ("All children are born Atheists; they have no idea of God" and George H. Smith (1979). According to Smith The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child without the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist. However, most would dispute this understanding of ''atheism''. One atheist writer who explicitly disagrees with such a broad definition is Ernest Nagel (1965): Atheism is not to be identified with sheer unbelief... Thus, a child who has received no religious instruction and has never heard about God, is not an atheist—for he is not denying any theistic claims. For Nagel atheism is the ''rejection'' of theism, not just the absence of theistic belief. However, this definition leaves open the question of what term can be used to describe those who lack theistic belief, but do not necessarily reject theism.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Ignosticism===

| |

| − | Ignosticism is a variation of explicit atheism which asserts that the question of whether or not deities exist is inherently meaningless. It is a popular view among many [[logical positivism|logical positivists]] such as [[Rudolph Carnap]] and [[A. J. Ayer]], who hold that talk of gods is literally [[nonsense]]. According to ignostics, "Does a god exist?" has the same logical truth value as "What color is Saturday?". Both question are nonsensical, and thus have no meaningful answers. Such theological statements cannot have any truth value, since they lack [[falsifiability]]. This refers to the fact that claims of transendence and metaphysic properties cannot be tested by empirical means and potentially rejected as a null hypothesis. This is because the meaning of the word "god" is solely a matter of [[semantics]] to ignostics, dealing with word use and technicalities rather than with existence and reality. Further, some ignostics state that the terminology being used by theologians has not been properly or consistently defined. In ''Language, Truth and Logic'', Ayer stated that theism, atheism and agnosticism were equally meaningless, insofar as they treat the question of the existence of God as a real question. However, there are varieties of atheism and agnosticism which do not necessarily agree that the question is meaningless, especially using the "lack of theism" definition of atheism. Despite Ayer's criticism of atheism as a concept (perhaps using the definition typically associated with [[strong atheism]]), ignosticism is still considered as a form of atheism in most religious classifications.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Gnostic and agnostic atheism===

| |

| − | Agnostic atheism is a fusion of atheism or [[nontheism]] with [[agnosticism]], the [[epistemology|epistemological]] position that the existence or nonexistence of deities is unknown ([[weak agnosticism]]) or unknowable ([[strong agnosticism]]). ''Agnostic atheism'''s definition varies, just as the definitions of agnosticism and atheism do. It may be a combination of lack of theism with [[strong agnosticism]], the view that it is impossible to know whether deities exist to any reliable degree. It may also be a combination of lack of theism with [[weak agnosticism]], the view that there is not currently enough information to decide whether or not a deity exists, but that there may be enough in the future. [[Apatheism]] often overlaps with agnostic atheism, as is the case with [[apathetic agnosticism]], a fusion of apatheism with strong agnostic atheism. Unlike ignostics, apathetic agnostics do not deny the question of God's existence. However, they are apathetic in regards to the answer of this question, claiming that God's existence or non-existence will have little effect on the human condition. Agnostic atheism is typically contrasted with [[agnostic theism]], the belief that deities exist even though it is impossible to even know that deities exist.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Agnostic atheism is also placed in contrast with gnostic atheism, the belief that there is enough information to determine that deities do not exist. ''Gnostic atheism'' is a more rarely used term, however, because often anyone who is not labeled as agnostic is assumed to be gnostic by default. Gnostic atheism also has varying meanings. When nontheism is combined with strong gnosticism, it denotes the belief that it is rational to be absolutely certain that deities do not, and perhaps cannot, exist. When nontheism is coupled with weak gnosticism, it denotes the belief that there is enough information to be reasonably sure that deities do not exist, but not absolutely certain. In addition, ''Gnostic atheism'' is sometimes used as a synonym of [[strong atheism]], and thus ''agnostic atheism'' is occasionally a synonym for [[weak atheism]]. This is similar to the more common confusion of the terms ''implicit atheism'' and ''explicit atheism'' with strong and weak atheism. It bears mentioning here that the term gnostic atheism should not be confused with [[Gnosticism]].

| |

| | | | |

| | ===Atheism in philosophical naturalism=== | | ===Atheism in philosophical naturalism=== |

| − | Despite the fact that many, if not most, atheists have preferred to claim that atheism is a lack of a belief rather than a belief in its own right, some atheist writers identify atheism with the [[naturalism (philosophy)|naturalistic world view]], and defend it on that basis. The case for naturalism is used as a positive argument for atheism. According to Thrower, negative atheism is understood primarily as a function of the current theism which it consistently reject. This, in Thrower's eyes, renders such atheism as relative. As an alternative, he proposes a way of looking at and interpreting events in the world, which he refers to as "naturalistic", in that it concerns nature. However, this worldview does not assert belief in any god beyond nature, and therefore is atheistic. Similarly, [[Julian Baggini]] argues that atheism must be understood not as a denial of religion, but as an affirmation of and commitment to the one world of nature. For Baggini, therefore, | + | Despite the fact that many, if not most, atheists have preferred to claim that atheism is a lack of a belief rather than a belief in its own right, some atheist writers identify atheism with the [[naturalism (philosophy)|naturalistic world view]] and defend it on that basis. The case for naturalism is used as a positive argument for atheism. For example, James Thrower proposes a "naturalistic" interpretation of events in the world, which takes nature as the paramount explanatory cause. As this worldview does not assert belief in any god beyond nature, it is therefore atheistic. Similarly, [[Julian Baggini]] argues that atheism must be understood not as a denial of religion, but instead as an affirmation of and commitment to the one world of nature. For Baggini, all unnatural (and supernatural) causes must be dismissed: "God is just one of the things that atheists don't believe in, it just happens to be the thing that, for historical reasons, gave them their name.<ref>Julian Baggini, ''Atheism: A Very Short Introduction'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0192804243), 17.</ref> This variation of atheism, then, denies not only god(s) but also the existence of souls and other supernatural entities. |

| − | the abundant evidence for the reality of the natural world and the lack thereof for for anything other phenomena confirms atheism. This other kind of phenomena for which there is no evidence is not limited to god by any means, however, as Baggini writes: "God is just one of the things that atheists don't believe in, it just happens to be the thing that, for historical reasons, gave them their name. (p.17). This variation of atheism, then, denies not only god but also the existence of souls and supernatural entities.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Antitheism=== | + | == Atheism and philosophy == |

| − | ''Antitheism'' (Anti-theism) typically refers to a direct opposition to [[theism]]. In this use, it is a form of critical [[strong atheism]]. While in other senses atheism merely denies the existence of deities, antitheists may go so far as to believe that theism is actually harmful for human beings. As well, they may simply be atheists who have little tolerance for views they perceive as [[irrationality|irrational]]. Strong atheists who are not antitheists may believe positively that deities do not exist, but not believe that theism is directly harmful or necessitates opposition to the extent antitheists do. Antitheism may sometimes overlap with [[ignosticism]], the view that theism is inherently meaningless, and may directly contradict [[apatheism]], the view that theism is irrelevant rather than dangerous. However, ''antitheism'' is also sometimes used, particularly in religious contexts, to refer to opposition to [[God]] or [[divine]] things, rather than an opposition to the belief in God. Using the latter definition, it may be possible — or perhaps even necessary — to be an antitheist without being an atheist or nontheist.

| + | Atheism has been historically used in two senses. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Pejorative Definitions===

| + | 1. Atheism has been a label given to a broad range of perspectives including pantheism and agnosticism, primarily by [[monotheism|monotheists]] or religious authorities. These perspectives did not necessarily deny [[mysticism|mystical]] or spiritual aspects of the world or of certain deities. The term “atheism” in this sense was coined in the sixteenth century to criticize positions that did not comply with the authorized views of the Christian church. The term is now extended to a wide variety of views whose contexts are quite different. |

| − | The first attempts to define or develop a typology of atheism were in religious [[apologetics]]. These attempts were expressed in terms and in contexts that reflected the religious assumptions and prejudices of the writers. Thus, the majority of such classifications depicted atheism as a licentious belief system. Regardless, a diversity of atheist opinion has been recognized at least since [[Plato]], and common distinctions have been established between ''practical atheism'' and ''speculative'' or ''contemplative atheism''.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Practical atheism was said to be caused by moral failure, hypocrisy, willful ignorance and infidelity. Atheists in the practical sense were those who ''behaved'' as though God, morals, ethics and social responsibility did not exist. [[Karen Armstrong]] notes that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the word 'atheist' had what were perhaps its most polemical connotations. For instance, John Wingfield, an author from that period claimed that the wicked, proud, and inscrutable were all atheists at heart. presumably denying good through their imperious actions. For the [[Wales|Welsh]] poet [[William Vaughan (Welsh writer and colonial investor)|William Vaughan]] (1577 [sic]–1641) those who raised rents or enclosed commons were unequivocally atheists. Similarly, English dramatist [[Thomas Nashe]] (1567-1601) put forward that ambitious, greedy, and gluttonous, individuals, as well as such societal dregs as prostitutes, were all essentially atheists. According to Armstrong, the term 'atheist' was a severe insult, and by no means would it be a title one bestowed upon themselves. These negative connotations have persisted and still exist in contemporary times. Maritain's typology of atheism (1953, Chapter 8) proved influential in Catholic circles; it was followed in the ''New Catholic Encyclopedia'' (see Reid, 1967). He identified, in addition to practical atheism, ''pseudo-atheism'' and ''absolute atheism'' (and subdivided theoretical atheism in a way that anticipated Flew). For an atheist critique of Maritain, see Smith (1979, Chapter 1, Section 5). According to the French Catholic philosopher Étienne Borne (1961, p.10), "Practical atheism is not the denial of the existence of God, but complete godlessness of action; it is a moral evil, implying not the denial of the absolute validity of the moral law but simply rebellion against that law."

| + | For example, [[Baruch Spinoza]] was denounced and labeled as an “atheist” by both [[Judaism|Jewish]] and [[Christianity|Christian]] authorities for over a century and [[Johann Gottlieb Fichte]] was expelled from [[university]] for the charge of “atheism.” Even [[Immanuel Kant]], a Christian thinker, was accused as being “atheistic.” |

| | | | |

| − | On the other hand, the existence of serious speculative atheism, which involves deep philosophical contemplation as to whether or not god actually exists, was often denied. That anyone might ''reason'' their way to atheism was thought to be impossible. Thus, speculative atheism was collapsed into a form of practical atheism, or conceptualized as hatred of God, or a fight against God. This is why Borne finds it necessary to say, "to put forward the idea, as some apologists rashly do, that there are no atheists except in name but only 'practical atheists' who through pride or idleness disregard the divine law, would be, at least at the beginning of the argument, a rhetorical convenience or an emotional prejudice evading the real question." (p.18) Martin (1990, p.465-466) suggests that practical atheism would be better described as ''alienated theism''. When denial of the existence of "speculative" atheism became unsustainable, atheism was nevertheless often repressed and criticized by narrowing definitions, applying charges of dogmatism, and otherwise misrepresenting atheist positions. One of the reasons for the popularity of euphemistic alternative terms like [[secularism|secularist]], [[empiricism|empiricist]], [[agnosticism|agnostic]], or [[Brights movement|bright]] is that ''atheism'' still has pejorative connotations arising from attempts at suppression and from its association with practical atheism. For example, the term ''godless'' is still used as an abusive epithet. Thinkers such as Gaskin (1989) have abandoned the term ''atheism'' in favor of ''unbelief'', citing the fac that the both the derogatory associations of the term and it vagueness in the public eye rendered atheism an undesireable lablel. Despite these considerations, for others ''atheist'' has always been the preferred name. [[Charles Bradlaugh]] once said, in debate with [[George Jacob Holyoake]], [[10 March]] [[1870]], cited in Bradlaugh Bonner (1908):

| + | 2. [[Materialism]]. This position denies the reality or existence of any deity, being transcendent or immanent. It should be sharply distinguished from [[pantheism]], [[agnosticism]], and religious naturalism. Materialist atheism has an explicit ontological commitment for the denial of the reality of spiritual or divine being in any form. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Atheism studies and statistics==

| + | Those who held this position include eighteenth-century French materialists such as [[Julien Offray de La Mettrie]], [[Baron d’Holbach]], and [[Denis Diderot]] and their ideological successors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries such as [[Ludwig Feuerbach]], [[Karl Marx]], [[Friedrich Engels]], [[Vladimir Lenin]], [[Josef Stalin]], and [[Mao Zedong]]. |

| − | As some governments have strongly promoted atheism, whilst others have strongly condemned it, atheism may be either over-reported or under-reported for different countries. There is a great deal of room for debate as to the accuracy of any method of estimation, as the opportunity for misreporting (intentionally or not) a belief system without an organized structure is high. Also, many surveys on religious identification ask people to identify themselves as "agnostics" or "atheists", which is potentially confusing, since these terms are interpreted differently, with some identifying themselves as being both atheist and agnostic. Additionally, many of these surveys only gauge the number of [[irreligion|irreligious]] people, not the number of actual atheists, or group the two together.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ===Distribution of atheists===

| + | During the [[Age of Enlightenment]], atheism became the philosophical position of a growing minority, headed by the openly atheistic works of [[Baron d'Holbach|d'Holbach]]. In the nineteenth century, atheism became a powerful political tool through the writings of Feuerbach, who claimed God was a fictional projection fabricated by man. This idea greatly influenced Marx, the founder of [[communism]], who believed that laborers turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations. Other atheists of the period included [[Friedrich Nietzsche]], [[Jean-Paul Sartre]] and [[Sigmund Freud]]. The overall popularity of atheism in the nineteenth century led Nietzsche to coin the aphorism "God is dead." By the twentieth century, along with the spread of [[rationalism]] and [[secular humanism]], atheism had become more widespread, particularly among scientists. |

| − | ====World estimates====

| |

| | | | |

| − | Though atheists are in the minority in most countries, they are relatively common in [[Western Europe]], [[Australia]], [[New Zealand]], [[Canada]], in former and present Communist states, and, to a lesser extent, in the [[United States]]. A 1995 survey attributed to the [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] indicates that the non-religious are about 14.7% of the world's population, and atheists around 3.8%.<ref>{{cite web

| + | Materialistic atheism challenges any position, policy, institution, and movement that is based upon the assumption of the existence of a deity and spiritual dimension. The most radical and socially affective form of materialistic atheism in contemporary society is [[Marxism]] and its extensions. Furthermore, those materialistic atheists who actively seek to undermine existing religions are sometimes labeled as militant atheists. During the period of [[communism|communist]] ascendancy, militant atheism enjoyed the full apparatus of the state, making it possible to attack religion and believers by every means imaginable with impunity. This included political, social, and military attacks on believers, and suppression of religion. |

| − | |url=http://www.zpub.com/un/pope/relig.html

| |

| − | |title=Worldwide Adherents of All Religions by Six Continental Areas, Mid-1995

| |

| − | |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref> This is similar to a 2002 survey by Adherents.com, which estimates the proportion of the world's people who are "secular, non-religious, agnostics and atheists" as about 14%.<ref>{{cite web

| |

| − | |url=http://adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html

| |

| − | |title=Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents

| |

| − | |publisher=Adherents.com | |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05}}</ref> A 2004 survey by the BBC in 10 countries showed the proportion of the population "who don't believe in God" varying between 0% and 44%, with an average close to 17% in the countries surveyed. About 8% of the respondents stated specifically that they consider themselves to be atheists.<ref name="UK secular">{{cite web

| |

| − | |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/wtwtgod/3518375.stm

| |

| − | |title=UK among most secular nations

| |

| − | |publisher=BBC News

| |

| − | |accessdate=2005-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref> A 2004 survey by the CIA in the World Factbook estimates about 12.5% of the world's population are non-religious, and about 2.4% are atheists.<ref>{{cite web

| |

| − | |url=http://cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/xx.html#People

| |

| − | |title=CIA World Factbook

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref> A 2004 survey by the [[Pew Research Center]] showed that in the United States, 12% of people under 30 and 6% of people over 30 could be characterized as non-religious.<ref>{{cite web

| |

| − | |url=http://people-press.org/reports/display.php3?PageID=757

| |

| − | |title=Part 8: Religion in American Life: The 2004 Political Landscape

| |

| − | |publisher=Pew Research Center

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref> A 2005 poll by AP/Ipsos surveyed ten countries. Of the developed nations, people in the [[United States]] had most certainty about the existence of god or a higher power (2% atheist, 4% agnostic), while [[France]] had the most skeptics (19% atheist, 16% agnostic). On the religion question, [[South Korea]] had the greatest percentage without a religion (41%) while [[Italy]] had the smallest (5%).<ref>{{cite web

| |

| − | |url=http://www.ipsos-na.com/news/pressrelease.cfm?id=2694

| |

| − | |title=AP/Ipsos Poll: Religious Fervor In U.S. Surpasses Faith In Many Other Highly Industrial Countries

| |

| − | |year=2005

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | Some studies have suggested that atheism is particularly prevalent among [[scientist]]s, a tendency already quite marked at the beginning of the 20th century, developing into a dominant one during the course of the century. In 1914, [[James H. Leuba]] found that 58% of 1,000 randomly selected U.S. [[natural science|natural scientists]] expressed "disbelief or doubt in the existence of God". The same study, repeated in 1996, gave a similar percentage of 60.7%; this number is 93% among the members of the [[National Academy of Sciences]]. Expressions of positive disbelief rose from 52% to 72%.<ref>{{cite journal

| + | ==Atheism and World Religions== |

| − | |url=http://www.stephenjaygould.org/ctrl/news/file002.html

| |

| − | |title=Leading scientists still reject God

| |

| − | |journal=Nature

| |

| − | |volume=394

| |

| − | |issue=6691

| |

| − | |page=313

| |

| − | |year=1998

| |

| − | |publisher=Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

| |

| − | |first=Edward J.

| |

| − | |last=Larson

| |

| − | |coauthors=Larry Witham

| |

| − | }}</ref> However, studies following Leuba's methods and questions only demonstrate disbelief in a specific type of God - a personal God which interacts directly with human beings. Restriction to this version of "God" makes the study unlikely to give a true sense of the percentage of atheists, and instead gives only a percentage of those rejecting this particular type of deity. Based on the questions in the study, many deists would have been classified as atheists. (See also [[The relationship between religion and science]].)

| |

| | | | |

| − | ====Atheism in Pacific nations==== | + | ===Ancient Greek and Roman=== |

| − | The 2001 Australian Census showed that a total of 15.5% were categorized as having "No Religion" (which includes non theistic beliefs such as [[Humanism]], [[atheism]], [[agnosticism]] and [[rationalism]]). 15.5% of respondents ticked "no religion", and a further 11.7% either did not state their religion or were deemed to have described it inadequately (there was a popular and successful campaign at the time to have people describe themselves as [[Jedi census phenomenon|Jedi]]).<ref>{{cite web

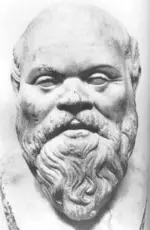

| + | [[image:socrates.png|thumb|150px|right|Socrates]] |

| − | |url=http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/9658217eba753c2cca256cae00053fa3?OpenDocument

| + | The oldest known variation of Western-style, philosophical atheism is attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher [[Epicurus]] around 300 B.C.E. The goal of the [[Epicureanism|Epicureans]] was mainly to alleviate fear of divine wrath by portraying it as irrational. One of the most eloquent expressions of Epicurean thought is found in [[Lucretius]]' ''On the Nature of Things'' (first century B.C.E.). He denied the existence of an [[afterlife]] and thought that if gods existed they were uninterested in human existence. For these reasons, they may be better described as [[materialism|materialists]] than atheists. Epicureans were not persecuted, but their teachings were controversial, and were harshly attacked by the mainstream schools of [[Stoicism]] and [[Neoplatonism]]. |

| − | |title=1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2003

| |

| − | |accessdate=2006-03-05

| |

| − | }}</ref>Despite the low atheism percentage weekly attendance at church services is only about 1.5 million, or about 7.5% of the population. According to the 2001 Census, nearly 40% of the New Zealand population has no religious affiliation.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ====Atheism in Asia====

| + | Many other Greek philosophers critiqued the then-prevalent [[henotheism|henotheistic]] beliefs. [[Xenophanes]], for instance, claimed that [[anthropomorphism|anthropomorphic]] and often immoral portrayals of the many gods were merely projections of humanity upon the divine. Ionic naturalists provided (pre-scientific) explanations for phenomena that had been previously been attributed to the gods. [[Democritus]] put forth the thesis that all phenomena in the world were merely transformations of eternal atoms, rather than anthropomorphic divinities. The [[Sophists]] criticized the various gods as products of human society and imagination. Critias, a famed dramatist and contemporary of [[Socrates]], had one of his characters put forth the view that gods existed merely to bolster and reify societal codes of morality. Atheist thought culminated in the Greek tradition with [[Theodoret of Cyrrhus]], who was the first to explicitly deny all forms of theism and the existence of any type of god. |

| − | According to Norris and Inglehart (2004, 1998), 6% of those in India do not believe in God. According to a 2004 survey commissioned by the BBC, less than 3% of Indians do not believe in God. The philosophy of Positive Atheism was begun by Gora (Shri [[Goparaju Ramachandra Rao]]) (1902-1975) in India. Gora founded the "[[Atheist Centre]]" and worked with [[Mahatma Gandhi]] to end untouchability and to work toward India's independence. He also worked with India's first Prime Minister [[Jawaharlal Nehru]], an atheist, urging him to support the formation of a secular government in the then predominantly Hindu nation of India.

| |

| | | | |

| − | The modern [[Atheist Centre]], run by Gora's children, incorporates many but not all of Gora's philosophies. It works to overturn the religious caste system and debunk [[pseudoscience]] and miracles. It hosts regular firewalking events, explaining the physics and allowing ordinary villagers to do something only holy men claimed to be able to do. <ref>Worth, Robert. Where atheists walk on coals. Commonweal; 6/2/95, Vol. 122 Issue 11, p17, 2p</ref>

| + | Politically speaking, these developments were problematic, as theism was the fundamental belief that supported the divine right of the State in both Greece and Rome. As such, any person who did not believe in the deities supported by the State was fair game to accusations of atheism, a capital crime. For political reasons, Socrates in [[Athens]] (399 B.C.E.) was accused of being ''atheos'' (or "refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). Early Christians in [[Rome]] were also considered subversive to the state religion and were thereby prosecuted as atheists. As such, it can be seen that charges of atheism (referring to the subversion of religion) were often used as a political mechanism by which to eliminate dissent. |

| | | | |