Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment refers to either the eighteenth century in European philosophy, or the longer period including the seventeenth century and the Age of Reason. It can more narrowly refer to the historical intellectual movement The Enlightenment, which advocated Reason as a means to establishing an authoritative system of aesthetics, ethics, government, and logic, which, they supposed, would allow human beings to obtain objective truth about the universe. Emboldened by the revolution in physics commenced by Newtonian kinematics, Enlightenment thinkers argued that the same kind of systematic thinking could apply to all forms of human activity.

The intellectual leaders regarded themselves as a courageous elite who would lead the world into progress from a long period of doubtful tradition, irrationality, superstition, and tyranny, which they imputed to the Dark Ages. The movement helped create the intellectual framework for the American and French Revolutions, the Latin American revolutions, and the Polish Constitution of May 3; and led to the rise of liberalism and capitalism. It is matched with the high baroque and classical eras in music, and the neo-classical period in the arts; it receives contemporary attention as being one of the central models for many movements in the modern period. The wide availability of knowledge through the production of encyclopedias served the Enlightenment cause of educating citizens to be capable of democracy.

Towards the end of the period, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) offered sapere aude as the motto of the Enlightenment - dare to know, suggesting that man had come of age, could now think for him/her-self free of the limitation of dogma that had previosuly hindered progress. Kant remained a theist but for many atheism was a direct result of the Enlightenment; religion was banished from the public square, becomming a private, domestic option. The Church increasingly also withdrew from the public square. Morality had to find a new ground on which to stand, apart from God. Many posited that values were self-eveident truths but others suggested that without any ethical source, morals were merely human opinions, which could change. Critics of the Enlightenemt say that virtue lost moral ground; no longer was it possible to move from a statement of fact to a judement about value, from what 'is' to 'ought' (Newbigin, 1986: 36). On the one hand, the confidence and energy that post-Enlightenment humanity has invested in scientific, medical and technological progress been hugely beneficial. Many cures and inventions have enhanced and saved million of lives. Many scientists do want to improve human life. On the other hand, science and technology has often disregarded ethics in terms of end-purpose, regarding progress as a good in and of itself regardless of utility. Nobody wants to turn the clock back but many want to return value to the center.

History of Enlightenment philosophy

Another important movement in seventeenth century philosophy, closely related to it, focused on belief and piety. Some of its proponents, such as George Berkeley, attempted to demonstrate rationally the existence of a supreme being. Piety and belief in this period were integral to the exploration of natural philosophy and ethics, in addition to political theories of the age. However, prominent Enlightenment philosophers such as Thomas Paine, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and David Hume questioned and attacked the existing institutions of both Church and State.

The eighteenth century also saw a continued rise of empirical philosophical ideas, and their application to political economy, government and sciences such as physics, chemistry and biology. I am more enlightened than you

The Enlightenment (if thought of as a short period) was preceded by the Age of Reason or (if thought of as a long period) by the Renaissance and the Reformation. It was followed by Romanticism.

The boundaries of the Enlightenment cover much of the seventeenth century as well, though others term the previous era "The Age of Reason." For the present purposes, these two eras are split; however, it is equally acceptable to think of them conjoined as one long period.

Europe had been ravaged by religious wars; when peace in the political situation had been restored, after the Peace of Westphalia and the English Civil War, an intellectual upheaval overturned the accepted belief that mysticism and revelation are the primary sources of knowledge and wisdom—which was blamed for fomenting political instability. Instead, (according to those that split the two periods), the Age of Reason sought to establish axiomatic philosophy and absolutism as foundations for knowledge and stability. Epistemology, in the writings of Michel de Montaigne and René Descartes, was based on extreme skepticism and inquiry into the nature of "knowledge." The goal of a philosophy based on self-evident axioms reached its height with Baruch (Benedictus de) Spinoza's Ethics, which expounded a pantheistic view of the universe where God and Nature were one. This idea then became central to the Enlightenment from Newton through to Jefferson. The ideas of Pascal, Leibniz, Galileo and other philosophers of the previous period also contributed to and greatly influenced the Enlightenment; for instance, according to E. Cassirer, Leibniz’s treatise On Wisdom ". . . identified the central concept of the Enlightenment and sketched its theoretical programme" (Cassirer 1979: 121–123). There was a wave of change across European thinking, exemplified by Newton's natural philosophy, which combined mathematics of axiomatic proof with mechanics of physical observation, a coherent system of verifiable predictions, which set the tone for what followed Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica in the century after. VAGINA

The Age of Enlightenment is also prominent in the history of Judaism, perhaps because of its conjunction with the political and social emancipation of many of Western Europe's Jews.

The Scottish Enlightenment

Scotand benefitted economically from the expansion of trade and commercial of the British Empire in the seventeenth through to the twentieth centuries. Many Scots served overseas in the colonial service as well as engaging in commerce. Traditionally close ties to France from the pre-Union with England period helped to forge intellectual links with French thought. Scotland's Universities were less subject to ecclesiastical control than Oxford and Cambridge were and a type of humanism flourished in the Scottish academy. Several writers, such Herman (2001) and Buchan (2003) point to the high level of Scotish contributions to Enlightenment thought, represented by such thinkers as Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746), David Hume (1711-1776) and Adam Smith (1723-1790). The concept of 'free trade', the mainstay of globalization as well as much of what came to be known as 'scientific method' developed within the Scottish Enlightenment. Herman explores how Scotland's 1707 union with England transformed the country from one of the poorest in Europe to an affluent and highly educated society, giving birth to the Scottish Enlightenment.

Key conflicts within Enlightenment-period philosophy

As with theology became a source of partisan debate, with different schools attempting to develop rationales for their viewpoints, which then, in turn, became generally accepted. Thus philosophers such as Spinoza searched for a metaphysics of ethics. This trend later influenced pietism and eventually transcendental searches such as those by Immanuel Kant.

Religion was linked to another concept which inspired a great amount of Enlightenment thought, namely the rise of the Nation-state. In medieval and Renaissance periods, the state was restricted by the need to work through a host of intermediaries. This system existed because of poor communication, where localism thrived in return for loyalty to some central organization. With the improvements in transportation, organization, navigation and finally the influx of gold and silver from trade and conquest, however, the state assumed more and more authority and power. Intellectuals responded with a series of theories on the purpose of, and limits of state power. Therefore, during The Enlightenment absolutism was cemented and a string of philosophers reacted by advocating limitation, from John Locke forward, who influenced both Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Enlightenment ideas influenced organisations seeking to effect state and social development, such as the Freemasons and Illuminati. And they ultimately had a profound effect on the actions of politically active individuals worldwide.

Within the period of the Enlightenment, these issues began to be explored in the question of what constituted the proper relationship of the citizen to the monarch or the state. The idea that society is a contract between individual and some larger entity, whether society or state, continued to grow throughout this period. A series of philosophers, including Rousseau, Montesquieu, Hume and Jefferson advocated this idea. Furthermore, thinkers of this age advocated the idea that nationality had a basis beyond mere preference. Philosophers such as Johann Gottfried von Herder reasserted the idea from Greek antiquity that language had a decisive influence on cognition and thought, and that the meaning of a particular book or text was open to deeper exploration based on deeper connections, an idea now called hermeneutics. The original focus of his scholarship was to delve into the meaning in the Bible and in order to gain a deeper understanding of it. These two concepts - of the contractual nature between the state and the citizen, and the reality of the nation beyond that contract, had a decisive influence in the development of liberalism, democracy and constitutional government which followed.

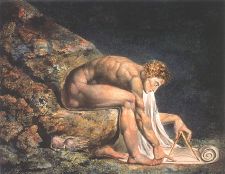

At the same time, the integration of algebraic thinking, acquired from the Islamic world over the previous two centuries, and geometric thinking which had dominated Western mathematics and philosophy since at least Eudoxus, precipitated a scientific and mathematical revolution. Sir Isaac Newton's greatest claim to prominence came from a systematic application of algebra to geometry, and synthesizing a workable calculus which was applicable to scientific problems. The Enlightenment was a time when the solar system was truly discovered: with the accurate calculation of orbits, such as Halley's comet, the discovery of the first planet since antiquity, Uranus by William Herschel, and the calculation of the mass of the Sun using Newton's theory of universal gravitation. These series of discoveries had a momentous effect on both pragmatic commerce and philosophy. The excitement engendered by creating a new and orderly vision of the world, as well as the need for a philosophy of science which could encompass the new discoveries, greatly influenced both religious and secular ideas. If Newton could order the cosmos with natural philosophy, so, many argued, could political philosophy order the body politic.

Within the Enlightenment, two main theories contended to be the basis of that ordering: divine right and natural law. It might seem that divine right would yield absolutist ideas, and that natural law would lead to theories of liberty. The writing of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet (1627-1704) set the paradigm for the divine right: that the universe was ordered by a reasonable God, and therefore his representative on earth had the powers of that God. The orderliness of the cosmos was seen as proof of God; therefore it was a proof of the power of monarchy. Natural law, began, not as a reaction against divinity, but instead, as an abstraction: God did not rule arbitrarily, but through natural laws that he enacted on earth. Thomas Hobbes, though an absolutist in government, drew this argument in Leviathan. Once the concept of natural law was invoked, however, it took on a life of its own. If natural law could be used to bolster the position of the monarchy, it could also be used to assert the rights of subjects of that monarch, that if there were natural laws, then there were natural rights associated with them, just as there are rights under man-made laws.

What both theories had in common was the need for an orderly and comprehensible function of government. The "Enlightened Despotism" of, for example, Catherine the Great of Russia and Frederick the Great of Prussia (a state within The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation), is not based on mystical appeals to authority, but on the pragmatic invocation of state power as necessary to hold back chaotic and anarchic warfare and rebellion. Frederick the Great was raised by his French governess, importing the Enlightenment to "Germany." Regularization and standardization were seen as good things because they allowed the state to reach its power outwards over the entirety of its domain and because they liberated people from being entangled in endless local custom. Additionally, they expanded the sphere of economic and social activity.

Thus rationalization, standardization and the search for fundamental unities occupied much of the Enlightenment and its arguments over proper methodology and nature of understanding. The culminating efforts of the Enlightenment: for example the economics of Adam Smith, the physical chemistry of Antoine Lavoisier, the idea of evolution pursued by Goethe, the declaration by Jefferson of inalienable rights, in the end overshadowed the idea of divine right and direct alteration of the world by the hand of God. It was also the basis for overthrowing the idea of a completely rational and comprehensible universe, and led, in turn, to the metaphysics of Hegel and the search for the emotional truth of Romanticism.

Role of the Enlightenment in later philosophy

The Enlightenment occupies a central role in the justification for the movement known as modernism. The neo-classicizing trend in modernism came to see itself as being a period of rationality which was overturning foolishly established traditions, and therefore analogized itself to the Encyclopediasts and other philosophes. A variety of 20th century movements, including liberalism and neo-classicism traced their intellectual heritage back to the Enlightenment, and away from the purported emotionalism of the 19th century. Geometric order, rigor and reductionism were seen as virtues of the Enlightenment. The modern movement points to reductionism and rationality as crucial aspects of Enlightenment thinking of which it is the inheritor, as opposed to irrationality and emotionalism. In this view, the Enlightenment represents the basis for modern ideas of liberalism against superstition and intolerance. Influential philosophers who have held this view are Jürgen Habermas and Isaiah Berlin.

This view asserts that the Enlightenment was the point where Europe broke through what historian Peter Gay calls "the sacred circle," where previous dogma circumscribed thinking. The Enlightenment is held, in this view, to be the source of critical ideas, such as the centrality of freedom, democracy and reason as being the primary values of a society. This view argues that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious and racial tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to apply rationality to every problem is considered to be the essential change. From this point on, thinkers and writers were held to be free to pursue the truth in whatever form, without the threat of sanction for violating established ideas.

With the end of the Second World War and the rise of post-modernity, these same features came to be regarded as liabilities - excessive specialization, failure to heed traditional wisdom or provide for unintended consequences, and the romanticization of Enlightenment figures - such as the Founding Fathers of the United States, prompted a backlash against both Science and Enlightenment based dogma in general. Philosophers such as Michel Foucault are often understood as arguing that the age of reason had to construct a vision of unreason as being demonic and subhuman, and therefore evil and befouling, so that by analogy to argue that rationalism in the modern period is, likewise, a construction. In their book, Dialectic of Enlightenment, Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno wrote a penetrating critique of what they perceived as the contradictions of Enlightenment thought: Enlightenment was seen as being at once liberatory and, through the domination of instrumental rationality tending towards totalitarianism. Foucault critiques the post-Enlightenment tendency to explain eveything according to a dominant mega-theory, so that eveything must fit the master-narrative. Truth, he says, is more subjective and all disciplines are created by elites who control the academy, who determine, often based on self-interests, the standards of normality. Once one method has been selected over others, alternatives become deviant. What does not conform is heresy. History, for example, is written by winners not losers, usually by men not women, by the elite not the workers. We need to unearth the hidden assumptions within texts; meaning may not be so much discovered within the text as supplied to, or read into, the narrative.

Alternatively, the Enlightenment was used as a powerful symbol to argue for the supremacy of rationalism and rationalization, and therefore any attack on it is connected to despotism and madness, for example in the writings of Gertrude Himmelfarb.

Muslim Critique

S H Nasr (1994) expresses Muslim criticism of the Enlightenment as separating knowledge from value. Western science and technology, he says, is immoral because there is no concern with the consequences of progress only with progress itself. Science no longer serves humanity but its own quest for yet more knowledge. His basic critique is that reason became detached from 'revelation', and thus also from values. Other Muslims argue that while Western science, post-Enlightenment, places trust in reason alone, Islamic science places its trust in God's revelation; Western science values science for its own sake, Islamic science regards itself as a type of worship; Western science claims impartiality, Islamic science claims a partiality towards what is true and beneficial for humanity; Western science reduces the world to what can be empirically verifeid, Islamic science admits the reality of the spiritual dimension (see Bennett: 120). Of course, such a contrast sets up a caricature of Western science over and against a very ideal view of Islamic science but it does represent a reasoned critique of post-Enlightenment assumptions. Nasr castigates contemporary Islamic fundamentalists for claiming that when they borrow Western technology that are retreiving what Islam have Europe through Spain since, says Nasr, they condemn as heretics the very philosophers from whom the West borrowed while Western science also stands on a foundation which they reject, that is, the primary of reason over revelation. There are also Christians who likewise have criticized the Enlightenment.

External links

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: The Enlightenment

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: The Counter-Enlightenment

- Introduction to the Enlightenment

- The greatest works of Enlightenment Literature

- 'L'esprit des Lumières a encore beaucoup à faire dans le monde d'aujourd'hui' by Tzvetan Todorov Le Monde March 4, 2006 url=http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3246,36-747585@51-696669,0.html

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, Clinton Muslims and Modernity, NY & London: Continuum, 2005 ISBN 082645481X

- Newbigin, Lesslie Foolishness to the Greeks, Grand Rapids, MI: Eeerdmans, 1986 ISBN 0802801765

- Nasr, S. H. Traditional Islam in the Modern World, London: Routledge, 1990 ISBN 0710303327

- Hill, Jonathan Faith in the Age of Reason, Downers Grove, IL: Lion/Intervarsity Press, 2004 ISBN 0830823603

- Cassirer, Ernst et al The Philosophy of the Enlightenment, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1979 ISBN 0691019630

- Hulluing, Mark Autocritique of Enlightenment: Rousseau and the Philosophes Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994 ISBN 0674054253

- Gay, Peter The Enlightenment: An Interpretation. NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996 ISBN 0704500175

- Melamed, Yitzhak Y, 'Salomon Maimon and the Rise of Spinozism in German Idealism', Journal of the History of Philosophy, Volume 42, Issue 1

- Jacob, Margaret Enlightenment: A Brief History with Documents Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000 ISBN 0312237014

- Munck, Thomas Enlightenment: A Comparative Social History, 1721-1794 London: Arnold; NY: Oxford University Press ISBN 034066326X

- Herman, Arthur How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of how Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World and Everything in It NY: Crown, 2001 ISBN 0609606352

- Brown, Stuart ed., British Philosophy in the Age of Enlightenment London: Routledge, 2002 ISBN ISBN:

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. 4 volumes. NY: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 ISBN

- Buchan, James Crowded with Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment: Edinburgh's Moment of the Mind NY: HarperCollins Publishers2003 ISBN 0060558881

- Louis Dupre, Louis The Enlightenment & the Intellctural Foundations of Modern Culture New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004 0300100329 ISBN

- Himmelfarb, Gertrude The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments, NY: Knopf: Distributed by Random House,2004 ISBN 1400042364

- Bronner, Stephen Eric Reclaiming the Enlightenment, NY: Columbia University Press, 2004 ISBN 0231126085

- May, Henry F The Enlightenment in America NY: Oxford University Press, 1976 ISBN 0195023676

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.