Virtue

The notion of virtue played a central role in ethical theorizing up until the Enlightenment. Major figures such as Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas, all place virtue at the centre of their moral theories. However, as a result of the influence of Kant and Utilitarian thinkers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, who focused mainly on actions rather than character, theorizing about virtue took something of a back seat until the latter part of the twentieth century. Recent years have seen a regeneration of philosophical work on virtue as a result of result of dissatisfaction with Kantian ethics and Utilitarianism.

A virtue is a state of a person’s character. People may be wise, courageous, modest, kind, self-controlled, and just. These are all virtues, which they may or may not possess. Virtues are dispositions of character. A disposition is a tendency to have certain responses in particular situations: responses such as emotions, perceptions, and actions. People who have the virtue of (e.g.) courage, then, are those with the disposition to ‘stand fast’ under trial, where this includes a complex of attitudes and emotions, behavior, and perceptions.

Virtues in world religions

All religions in the world recognize the importance of morality in our lives, teaching a sense of social and moral responsibility for orderliness and descipline in our behavior, so that we may be able to survive or live peacefully on earth and beyond. Morality involves virtues such as compassion, humility, tolerance, truthfulness, diligence, and perseverance, and these virtues seem to have originated from world religions.

Hinduism

Hinduism regards dharma (righteousness) as the first chief aim of human life, encouraging us to cultivate virtues and do good deeds in order for us to be liberated from the chain of karma. So, the Bhagavad Gita teaches: "O Arjuna there never exists destruction for one in this life nor in the next life; since dear friend anyone who is engaged in virtuous acts never comes to evil."[1] Although the actions of humans are usually caused by mixtures of the three different qualities of sattva (purity), rajas (vitality), and tamas (darkness), one is encouraged to increase the quality of sattva by cultivating virtues and doing good deeds. Virtues are modes of sattva, and they include altruism, moderation, honesty, cleanliness, protection of the earth, universality, peace, non-violence, and reverance for elders.

Buddhism

The Eightfold Path of Buddhism, consisting of right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration, is a course on virtuous living on the path of righteousness, which would lead to the cessation of dukkha (suffering) and the achievement of bodhi (enlightenment). Buddhism has a few other ways of classifying virtues. It has the four Brahmavihāras (abodes of Brahma), known also as the four "immeasurables" (apramāṇa in Sanskrit), which are maitrī/mettā (loving-kindness or benevolence), karuṇā (compassion), mudita (sympathetic joy), and upekṣā/upekkhā (equanimity); and they may be more properly regarded as virtues in the European sense. Theravada Buddhism has developed the Ten Perfections (dasapāramiyo in Pāli; singular: pāramī in Pāli; pāramitā in Sanskrit), shown in the second chapter of the Buddhavamsa, part of its Pali Canon, and they are dāna pāramī (generosity), sīla pāramī (good conduct), nekkhamma pāramī (renunciation), paññā pāramī (wisdom), vīrya pāramī (diligence), khanti pāramī (patience), sacca pāramī (truthfulness), adhiṭṭhāna pāramī (determination), mettā pāramī (loving-kindness or benevolence), and upekkhā pāramī (equanimity). A stress on the importance of such virtues can be seen in the following passage in the Dhammapada, part of the Pali Canon: "Sandal-wood or Tagara, a lotus-flower, or a Vassikî, among these sorts of perfumes, the perfume of virtue is unsurpassed."[2] Mahayana Buddhism lists the Six Perfections (şaţpāramitā in Sanskrit) in the Lotus Sutra, and they are dāna pāramitā (generosity), śīla pāramitā (good conduct), kṣanti pāramitā (patience), vīrya pāramitā (diligence), dhyāna pāramitā (one-pointed concentration), and prajñā pāramitā (wisdom). Four more Perfections are listed in Mahayana Buddhism's Dasabhumika Sutra: upaya pāramitā (skillful means), praṇidhāna pāramitā (determination), bala pāramitā (spiritual power), and jñāna pāramitā (knowledge).

Chinese religions

"Virtue," translated from Chinese de (德), is an important concept in Chinese religions, particularly Daoism and Confucianism. De originally meant normative "virtue" in the sense of "personal character, inner strength, or integrity," but semantically changed to moral "virtue, kindness, or morality." Note the semantic parallel for English "virtue," with an archaic meaning of "inner potency or divine power" (as in "by virtue of") and a modern one of "moral excellence or goodness." In Daoism the concept of de is rather subtle, pertaining to the virtue or ability that an individual realizes by following the Dao ("the Way").

Confucianism played a key role by presenting its teaching of virtues to Far Eastern countries such as Korea and Japan beside China as they built their social systems. Confucian moral manifestations of virtue include ren (仁; humanity), xiao (孝; filial piety), and zhong (忠; loyalty). Originally, ren had the archaic meaning of "virility" in the Confucian Book of Poems and then progressively took on shades of ethical meaning.[3] One important normative value in much of Chinese thinking is that one's social status should result from the amount of virtue that one demonstrates rather than from one's birth. In the Analects, Confucius explains de: "He who exercises government by means of his virtue may be compared to the north polar star, which keeps its place and all the stars turn towards it."[4]

Judaism

The Hebrew Bible contains the Ten Commandments and 613 other commandments. So, it gives the impression that Judaism is simply about following rules. But, when teaching these commandmentsand, Judaism actually aims at fostering moral vitues in the hearts of people, so that human relationships may become more harmonious for the betterment of the world. So, one striking virtue in Judaism is compassion, resembling the compassionate God.

Sorrow and pity for one in distress, creating a desire to relieve, is a feeling ascribed alike to man and God: in Biblical Hebrew, ("riḥam," from "reḥem," the mother, womb), "to pity" or "to show mercy" in view of the sufferer's helplessness, hence also "to forgive" (Hab. iii. 2); , "to forbear" (Ex. ii. 6; I Sam. xv. 3; Jer. xv. 15, xxi. 7.) The Rabbis speak of the "thirteen attributes of compassion." The Biblical conception of compassion is the feeling of the parent for the child. Hence the prophet's appeal in confirmation of his trust in God invokes the feeling of a mother for her offspring (Isa. xlix. 15). [5]

Lack of compassion, by contrast, marks a people as cruel (Jer. vi. 23). The repeated injunctions of the Law and the Prophets that the widow, the orphan and the stranger should be protected show how deeply, it is argued, the feeling of compassion was rooted in the hearts of the righteous in ancient Israel.[6]

A classic articulation of the Golden Rule (see above) came from the first century Rabbi Hillel the Elder. Renowned in the Jewish tradition as a sage and a scholar, he is associated with the development of the Mishnah and the Talmud and, as such, one of the most important figures in Jewish history. Asked for a summary of the Jewish religion in the most concise terms, Hillel replied (reputedly while standing on one leg): "That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah. The rest is the explanation; go and learn." [7]

Post 9/11, the words of Rabbi Hillel are frequently quoted in public lectures and interviews around the world by the prominent writer on comparative religion Karen Armstrong.

Islam

of God the Compassionate, the Merciful.]]

In the Muslim tradition the Qur'an is, as the word of God, the great repository of all virtue in earthly form, and the Prophet, particularly via his hadiths or reported sayings, the exemplar of virtue in human form.

The very name of Islam, meaning "acceptance," proclaims the virtue of submission to the will of God, the acceptance of the way things are. Foremost among God's attributes are mercy and compassion or, in the canonical language of Arabic, Rahman and Rahim. Each of the 114 chapters of the Qur'an, with one exception, begins with the verse, "In the name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful". [8]

The Arabic for compassion is rahmah. As a cultural influence, its roots abound in the Qur'an. A good muslim is to commence each day, each prayer and each significant action by invoking God the Merciful and Compassionate, i.e. by reciting Bi Ism-i-Allah al-Rahman al-Rahim. The Muslim scriptures urge compassion towards captives as well as to widows, orphans and the poor. Traditionally, Zakat, a toll tax to help the poor and needy, was obligatory upon all muslims (9:60). One of the practical purposes of fasting or sawm during the month of Ramadan is to help one empathize with the hunger pangs of those less fortunate, to enhance sensitivity to the suffering of others and develop compassion for the poor and destitute. [9]

The list of Muslim virtues is a long one: prayer, repentance. honesty, loyalty, sincerity, frugality, prudence, moderation, self-restraint, discipline, perseverance, patience, hope, dignity, courage, justice, tolerance, wisdom, good speech, respect, purity, courtesy, kindness, gratitude, generosity and contentment.

Christianity

In Christianity, the theological virtues are faith, hope and charity or love/agape, a list which comes from 1 Corinthians 13:13 (νυνι δε μενει πιστις ελπις αγαπη τα τρια ταυτα μειζων δε τουτων η αγαπη pistis, elpis, agape). These are said to perfect one's love of God and Man and therefore (since God is super-rational) to harmonize and partake of prudence.

There are many listings of virtue additional to the traditional Christian virtues (faith, hope and love) in the Christian Bible. One is the so-called "Fruit of the Spirit," found in Galatians 5:22-23:

- "By contrast, the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. There is no law against such things."

The Holy Bible : New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989).

22 Ὁ δὲ καρπὸς τοῦ πνεύματός ἐστιν ἀγάπη χαρὰ εἰρήνη, μακροθυμία χρηστότης ἀγαθωσύνη, πίστις 23 πραΰτης ἐγκράτεια· κατὰ τῶν τοιούτων οὐκ ἔστιν νόμος. Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger and Allen Wikgren, The Greek New Testament, 4th ed. (Federal Republic of Germany: United Bible Societies, 1993, c1979).

Historical overview

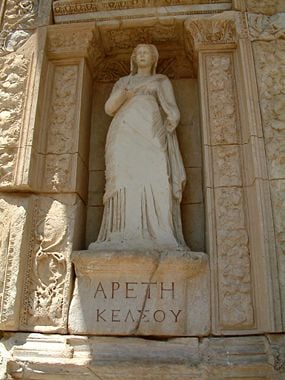

Virtue (arête) is, along with well-being (eudaimonia), one of the two central concepts in ancient Greek ethics. Greek ethical thinking focuses on character states known as aretai ("virtues"), which are understood to be distinct properties of the soul. For example, someone with the virtue of justice is concerned with the fair treatment of other people; someone with the virtue of courage responds correctly in situations of trial (particularly in warfare) by overcoming his fear. And something similar is thought to be true of self-control or moderation, piety, and wisdom. Each virtue ensures that its possessor acts in the correct ways pertaining to a situation that he or she might encounter over a life. Possessing the virtues ensures that one practices good (agathon) and fine (kalon) courses of action.

Socrates

Socrates as he appears in Plato's writings was the first in the western intellectual tradition to make systematic investigations into the virtues.[10] Socrates' thinking on the virtues seems to have two main distinctive features. Firstly, Socrates seems to think that wisdom is a sort of knowledge about how best to use all the other virtues. In Plato's dialogue, Euthydemus (also Meno), Socrates gets Cleinias to agree that wisdom is a kind of knowledge. He draws an analogy between wisdom and a carpenter's knowledge of his trade or craft (technê), claiming that the successful carpenter must not only have proper tools but know how to use them. Here Socrates position seems to be that goods such as health, wealth, and beauty, as well as the moral virtues of justice, moderation, courage, and wisdom (279a-c) are all subordinate to wisdom.

The second distinctive feature of Socrates' thinking is that he, in contrast with common Greek thought, seems to have maintained that there is strictly only one virtue. This is sometimes called his doctrine of the unity of the virtues. In Plato’s dialogue, Protagoras, Protagoras defends the view that the virtues are distinct traits so that a person can possess one virtue without possessing the others (329d-e). Some people are courageous without being wise, and some are wise without being courageous (and so on). Socrates argues against this, maintaining that apparently separate virtues of piety, self-control, wisdom, courage and justice are in some way one and the same thing -– a particular type of knowledge. His view seems to be that the distinction between virtues is nothing other than the distinction between different spheres of application of the same state of knowledge. Given this unity of the virtues, it follows that a person cannot possess one virtue independently of the others: if he possesses one, he must possess them all.

Plato and Aristotle

Plato's view of virtue may be understood as a development of Socrates'. In his greatest work, Republic, Plato raises the question of why virtues are valuable to their possessors. He argues that virtues are states of the soul, and that the just person is someone whose soul is ordered and harmonious, with all its parts functioning properly to the person's benefit. By contrast, Plato argues, the unjust person's soul, without the virtues, is chaotic and at war with itself, so that even if he could satisfy most of his desires, his lack of inner harmony and unity would thwart any chance he has of achieving eudaimonia.

Aristotle's account of the virtues, as presented in the Nicomachean Ethics is by far the most influential of the ancient accounts of the virtues. The fact that many modern thinkers consider themselves to be "neo-Aristotelians" is testimony to this fact. Aristotle see the virtues as flexible dispositions of character, acquired by moral education training, which are displayed in action as well as patterns of cognitive and emotional reaction. This basic account of virtue is accepted by most modern philosophers and will be considered in some detail below.

Both Plato and Aristotle subscribe to variations of Socrates' doctrine of the unity of the virtues. Aristotle's version diverges from Socrates' doctrine by recognizing different virtues, but it endorses the Socratic idea that one cannot have one virtue without having them all. This is because of the emphasis he places on the intellectual virtue of phronesis ("practical wisdom"). Aristotle maintains that one cannot properly possess any of the virtues unless one has developed the virtue of practical wisdom. Conversely, if one has practical wisdom, then one has all the virtues.

Thomas Aquinas

The medieval theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas developed and extended Aristotle’s theory into a Christian context, introducing another category of virtues called "theological" virtues. The three main theological virtues of faith, hope, and love, have God as their immediate object. According to Aquinas, non-Christian people can not display theological virtues, although they can manifest the other, non-theological virtues such as courage. However, Aquinas seems to hold that all the non-theological virtues such as those recognized by the Greeks are subordinate and grounded in the virtue called charity, which is a theological virtue.

Kantianism and utilitarianism

Since the time of the Enlightenment, moral theorizing has shifted its focus from the issue of what sort of person one should be to that of what one ought to do. Thus, the main questions to be addressed have become: What actions should one perform?; and, Which actions are right and which ones wrong? Questions such as: Which traits of character ought one to develop?; and, Which traits of character are virtues, and which ones vices?, have been ignored. For instance, according to classical utilitarians such as as Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), one ought to do actions that promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number. The principle of utility is a criterion of rightness, and one's motive in acting has nothing to do with the rightness of an action. Similarly, for Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), one ought to act only on maxims that can consistently be willed as universal laws. Kant, of course, does give motivation a central place in his theory of morality, according to which the morally virtuous person is someone who is disposed to act from the motive of duty. But this idea, of someone who always does the right thing from the desire to do the right thing, may not be an accurate picture of the virtues of the moral agent's character. This trend after the Enlightenment continued until the middle of the twentieth century.

Twentieth century

Interest in the concept of virtue and ancient ethical theory more generally has enjoyed a tremendous revival in the twentieth century. This is largely as a result of Elizabeth Anscombe's 1958 article, "Modern Moral Philosophy,"[11] which argues that duty-based conceptions of morality are incoherent because they are based on the idea of a law but without a lawgiver. Her point is roughly that a system of morality conceived along the lines of the Ten Commandments, as a system of rules for action, depends on someone having actually made these rules. However, in the modern climate, which is unwilling to accept that morality depends on God in this way, a rule-based conception of morality is stripped of its metaphysical foundation. Anscombe recommends a return to the virtue ethical theories of the ancients, particularly Aristotle, which ground morality in eudaimonia, the interests and well-being of human moral agents, and can do so without appeal to any questionable metaphysic. The primary focus of this virtue ethics is not discrete actions but rather: What sort of person should one be, try to be, or want to be? The focus is the agent's character.

Contemporary virtue ethics

Many philosophers today follow ancient ethical thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle, in situating virtue at the centre of their ethical theories. They criticize utilitarianism and Kantian ethics, by stating that they neglect the importance of moral motivation, or provide a distorted conception of moral motivation. As a result, virtue ethics has come to be recognized as a promising alternative to utilitarianism and Kantianism in the sphere of normative theory.

The nature of virtue

Contemporary virtue ethics shares much in common with Aristotle. Most modern thinkers adopt Aristotle's view that virtues are flexible dispositions of character, which are displayed in specific types of actions, as well as cognitive and emotional reactions. This conception of virtues may be explained by considering its various components in turn.

Firstly, virtues are states of a person's character. Judging someone to be courageous or wise, for example, is to make a judgment targeted at the character of a person rather than specific actions. We call actions right and wrong, but when we say that a person is generous, we are making a claim about the moral worth of the person concerned. We are saying that he or she possesses a certain virtuous trait of character.

Secondly, a virtue is a disposition of a person's character. A disposition is a tendency to have certain responses in particular situations: responses such as emotions, perceptions, and actions. It is important to notice that the idea of a disposition is made out in terms of the situations in which certain characteristics would be displayed. To say that a person is a generous man is to say more than he has behaved generously in the past. If he has the virtue of generosity, then he will very likely behave generously in situations in which generosity is called for. This, then, has something to do with enduring patterns of response, which characterize a person when he or she is in situations of a given type.

Thirdly, the possession of a virtue entails a wide range of responses including actions, perceptions, attitudes and emotions. In this vein, Rosalind Hursthouse helpfully characterizes virtues as multi-track dispositions. She says: "A virtue is not merely a tendency to do what is morally desirable or required. Rather, it is to have a complex mindset. This includes emotions, choices, desires, attitudes, interests, and sensibilities."[12] A person who fully possesses a virtue is effortlessly moved by the range of considerations pertinent to the situation in which he or she acts, and displays the emotions particular to the virtue in question. This is to recognize a distinction drawn by Aristotle between the virtuous person and the strong-willed person who acts correctly but has to control his desires and emotions, which are not properly tuned to the display of the virtue in question. The main point is that a full virtue requires a harmony between one's actions and emotions and attitudes. Someone who does not possess this harmony may act correctly but will nonetheless fail to be (fully) virtuous.

Main differences with Aristotle's conception

But, the contemporary account diverges from Aristotle's conception in a number of ways.

Firstly, the scope of virtue in the contemporary account is not as broad as that in Aristotle's conception. The word Greek word arête is usually translated into English as "virtue." One problem with this translation is that we are inclined to understand virtue in a moral sense, which is not always what the ancients had in mind. For the Greeks, arête pertains to all sorts of qualities we would not regard as relevant to ethics, such as the physical beauty of a woman and the high speed of a horse. So it is important to bear in mind that the sense of virtue operative in ancient ethics is not exclusively moral and includes more than moral states such as wisdom, courage, and compassion.

Secondly, the contemporary conception is not as teleological as Aristotelian ethics. According to Aristotle, virtuous activity is to achieve well-being or happiness (eudaimonia) in our life, and for that purpose we have to have our virtue in the sense of arête function excellently. For example, rationality is peculiar to human beings, and the function (ergon) of a human being will involve the exercise of his rational capacities to the highest degree to attain well-being. The contemporary account, by contrast, is not necessarily a teleological ethics).

Thirdly, contemporary virtue theory seems to take account of the fact that what counts as a virtue is influenced by historical factors. So, it does not necessarily agree with Aristotle's list of the virtues. A particularly conspicuous example of this is megalopsuchia ("greatness of soul") Aristotle regards as a virtue. Contemporary theory would not accept it as a virtue. Another example is the virtue of kindness, which Aristotle does not have on his list of virtues, but which contemporary virtue theory accepts from the Christian tradition.

Fourthly, contemporary theory is more hesitant about Socrates' doctrine of the unity of the virtues than Aristotle. Of course, Aristotle diverges from Socrates in that he recognizes the real difference of the virtues; but, he at least endorses the Socratic idea that one cannot have one virtue without having them all, based on the intellectual virtue of phronesis ("practical wisdom") he emphasizes. Aristotle thus maintains that if one has phronesis, one has all the virtues. Most contemporary thinkers will not recognize the strong sort of dependency between practical wisdom and courage, for example.[13]

Virtue and vice

The opposite of a virtue is a vice. One way of organizing the vices is as the corruption of the virtues. Thus the cardinal vices would be folly, venality, cowardice and lust. The Christian theological vices would be blasphemy, despair, and hatred.

However, as Aristotle noted, the virtues can have several opposites. Virtues can be considered the mean between two extremes. For instance, both cowardice and rashness are opposites of courage; contrary to prudence are both over-caution and insufficient caution. A more "modern" virtue, tolerance, can be considered the mean between the two extremes of narrow-mindedness on the one hand and soft-headedness on the other. Vices can therefore be identified as the opposites of virtues, but with the caveat that each virtue could have many different opposites, all distinct from each other.

Capital vices and virtues

The seven capital vices or "seven deadly sins" suggest a classification of vices and were enumerated by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century. The Catechism of the Catholic Church mentions them as "capital sins which Christian experience has distinguished, following Saint John Cassian and Saint Gregory the Great. "Capital" here means that these sins stand at the head (Latin caput) of the other sins which proceed from them, e.g., theft proceeding from avarice and adultery from lust.

These vices are pride, envy, avarice, anger, lust, gluttony, and sloth. The opposite of these vices are the following virtues: meekness, humility, generosity, tolerance, chastity, moderation, and zeal (meaning enthusiastic devotion to a good cause or an ideal). These virtues are not exactly equivalent to the Seven Cardinal or Theological Virtues mentioned above. Instead these capital vices and virtues can be considered the "building blocks" that rule human behavior. Both are acquired and reinforced by practice and the exercise of one induces or facilitates the others.

Ranked in order of severity as per Dante's Divine Comedy (in the Purgatorio), the seven deadly vices are:

- Pride or Vanity — an excessive love of self (holding self out of proper position toward God or fellows; Dante's definition was "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbor"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, pride is referred to as superbia.

- Avarice (covetousness, Greed) — a desire to possess more than one has need or use for (or, according to Dante, "excessive love of money and power"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, avarice is referred to as avaritia.

- Lust — excessive sexual desire. Dante's criterion was "lust detracts from true love." In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, lust is referred to as luxuria.

- Wrath or Anger — feelings of hatred, revenge or even denial, as well as punitive desires outside of justice (Dante's description was "love of justice perverted to revenge and spite"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, wrath is referred to as ira. #Gluttony — overindulgence in food, drink or intoxicants, or misplaced desire of food as a pleasure for its sensuality ("excessive love of pleasure" was Dante's rendering). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, gluttony is referred to as gula.

- Envy or jealousy; resentment of others for their possessions (Dante: "Love of one's own good perverted to a desire to deprive other men of theirs"). In the Latin lists of the Seven Deadly Sins, envy is referred to as invidia.

- Sloth or Laziness; idleness and wastefulness of time allotted. Laziness is condemned because others have to work harder and useful work can not get done. (also accidie, acedia)

Several of these vices interlink, and various attempts at causal hierarchy have been made. For example, pride (love of self out of proportion) is implied in gluttony (the over-consumption or waste of food), as well as sloth, envy, and most of the others. Each sin is a particular way of failing to love God with all one's resources and to love fellows as much as self. The Scholastic theologians developed schema of attribute and substance of will to explain these sins.

The fourth century Egyptian monk Evagrius Ponticus defined the sins as deadly "passions," and in Eastern Orthodoxy, still these impulses are characterized as being "Deadly Passions" rather than sins. Instead, the sins are considered to invite or entertain these passions. In the official Catechism of the Catholic Church published in 1992 by Pope John Paul II, these seven vices are considered moral transgression for Christians and the virtues should complement the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes as the basis for any true Morality.

Notes

- ↑ "The Bhagavad-Gita in English," 6:40. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Dhammapada," 4:55. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ↑ On the origins and transformations of this concept, see Lin Yu-sheng, "The Evolution of the Pre-Confucian Meaning of Jen and the Confucian Concept of Moral Autonomy," Monumenta Serica 31 (1974-75): 172-204.

- ↑ Confucious, The Analects of Confucious, II, 1. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedautogenerated1 - ↑ http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=699&letter=C&search=compassion |The Jewish Enclopedia

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 31a. See also the ethic of reciprocity or "The Golden rule."

- ↑ http://www.usc.edu/dept/MSA/fundamentals/tawheed/conceptofgod.html | University of Southern California

- ↑ http://www.milligazette.com/Archives/15122001/1512200144.html

- ↑ What we know of Socrates' philosophy is almost entirely derived from Plato's Socratic dialogues. Scholars typically divide Plato's works into three periods: the early, middle, and late periods. They tend to agree also that Plato's earliest works quite faithfully represent the teachings of Socrates, and that Plato's own views, which go beyond those of Socrates, appear for the first time in the middle works such as Phaedo and Republic.

- ↑ G. E. M. Anscombe, "Modern Moral Philosophy." Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ↑ Rosalind Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ↑ For more on phronesis, see Sarah Broadie, Ethics with Aristotle (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anscombe, G.E.M. "Modern Moral Philosophy." Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa contra Gentiles (A Treatise against the Unbelievers)

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologiae (A Treatise on Theology), Parts I [1265-8], I-II [1271-2], II-II [c.1271], III [1272-3]

- Aristotle (c. midfourth century B.C.E.) Nicomachean Ethics, trans. W.D. Ross, revised by J. Urmson, ed. and revised by J. Barnes in The Complete Works of Aristotle, vol. 2, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Broadie, Sarah. 1993. Ethics with Aristotle. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195085604

- Crisp, Roger, and Michael Slote, eds. 1997. Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Foot, Philippa. 1978. Virtues and Vices. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Foot, Philippa. 2001. Natural Goodness. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press

- Hume, D. 1751. "An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals," in Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding and Concerning the Principles of Morals, ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge, revised by P.H. Nidditch, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 3rd edn, 1975.

- Hursthouse, Rosalind. 1999. On Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lin, Yu-sheng. "The Evolution of the Pre-Confucian Meaning of Jen and the Confucian Concept of Moral Autonomy." Monumenta Serica 31 (1974- 1975): 172-204.

- MacIntyre, A. 1981. After Virtue. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- McDowell, John. 1979. "Virtue and Reason." Monist 62: 331-350

- McDowell, John. 1980. "The Role of Eudaimonia in Aristotle's Ethics." reprinted in Essays on Aristotle's Ethics, ed. Amelie Oksenberg Rorty. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, 359-376

- McDowell, John. 1995. "Two Sorts of Naturalism." in Virtues and Reasons, R. Hursthouse, G. Lawrence and W. Quinn (eds.) Oxford, Oxford University Press, 149-179

- Nietzsche, F. 1887. Zur Genealogie der Moral, trans. C. Diethe, On the Genealogy of Morality. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Plato. Gorgias, trans. D.J. Zeyl. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

- Plato. Republic, trans. G.M.A. Grube, revised by C.D.C. Reeve, Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1992. (His fullest account, political as well as ethical, of the nature and value of the virtues.)

- Rachels, J. 2003. The Elements of Moral Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Stocker, Michael. 1976. "The Schizophrenia of Modern Ethical Theories." Journal of Philosophy 14:453-466

- Trianosky, Gregory Velazco y. 1990. "What is Virtue ethics All About?" American Philosophical Quarterly 27: 335-344, reprinted in Statman 1997a

- Williams, B. 1972. Morality: An Introduction to Ethics. New York: Harper & Row.

External links

all links Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- Cardinal, Contrary, Heavenly and other Virtues

- The Four Virtues

- The Virtues Project

- Virtues Project International

- VirtueScience.com

- Virtue Magazine

- Cardinal Virtues, Catholic Encyclopedia

- Summa Theologica "Second Part of the Second Part"

- Virtue epistemology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Virtue Ethics, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Justice as a virtue, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Philosophy Sources on Internet EpistemeLinks

- Guide to Philosophy on the Internet

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.