Difference between revisions of "Rhea (bird)" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) (added article from wikipedia) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

==Human interaction== | ==Human interaction== | ||

Rheas have many uses in South America. Feathers are used for feather dusters, skins are used for cloaks or leather, and their meat is a staple to many people.<ref name="Davies" /> | Rheas have many uses in South America. Feathers are used for feather dusters, skins are used for cloaks or leather, and their meat is a staple to many people.<ref name="Davies" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Greater or American Rhea== | ||

| + | {{Taxobox | ||

| + | | name = Greater Rhea | ||

| + | | image = Rhea side profile.jpg | ||

| + | | image_width = 240px | ||

| + | | status = NT | ||

| + | | status_system = iucn3.1 | ||

| + | | status_ref = <ref name = "IUCN">BirdLife International(2009)</ref> | ||

| + | | regnum = [[Animalia]] | ||

| + | | phylum = [[Chordata]] | ||

| + | | classis = [[Aves]] | ||

| + | | subclassis = [[Neornithes]] | ||

| + | | infraclassis = [[Palaeognathae]] | ||

| + | | ordo = [[Struthioniformes]] | ||

| + | | familia = [[Rheidae]] | ||

| + | | genus = ''[[Rhea (bird)|Rhea]]'' | ||

| + | | species = '''''R. americana''''' | ||

| + | | binomial = ''Rhea americana'' | ||

| + | | binomial_authority = ([[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]], 1758)<ref name="SN">Brands, S. (2008)</ref> | ||

| + | | subdivision_ranks = [[sub-species]] | ||

| + | | subdivision = ''R. americana americana'' <small>([[Carolus Linnaeus|Linnaeus]], 1758)<ref name="SN" /></small><br> | ||

| + | ''R. americana intermidia'' <small>([[Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild|Rotschild]] & [[Charles Chubb (ornithologist)|Chubb]], 1914)<ref name="SN" /></small><br> | ||

| + | ''R. americana nobilis'' <small>([[Pierce Brodkorb|Brodkorb]], 1939)<ref name="SN" /></small><br> | ||

| + | ''R. americana araneipes'' <small>([[Pierce Brodkorb|Brodkorb]], 1938)<ref name="SN" /></small><br> | ||

| + | ''R. americana albescens'' <small>([[Arribálzaga]] & [[Holmberg]], 1878)<ref name="SN" /></small> | ||

| + | | range_map = Rhea americana Distribuzione.jpg | ||

| + | | range_map_width = 240px | ||

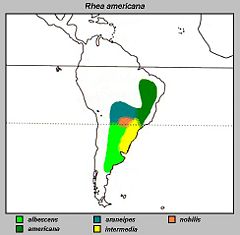

| + | | range_map_caption = Distribution of subspecies | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The '''Greater Rhea''' ('''''Rhea americana''''') is also known as the '''Grey''', '''Common''' or '''American Rhea'''. The native range of this [[flightless bird]] is the eastern part of [[South America]]; it is not only the largest [[species]] of the [[genus]] ''[[Rhea (bird)|Rhea]]'' but also the largest [[Americas|American]] bird alive. It is also notable for its reproductive habits, and for the fact that a group has established itself in [[Germany]] in recent years. In its native range, it is known as '''''[[ñandú]]''''' ([[Spanish (language)|Spanish]]) or '''''ema''''' ([[Portuguese (language)|Portuguese]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Taxonomy== | ||

| + | The Greater Rhea, '''''Rhea americana''''', derives its name from [[Rhea (mythology)|Rhea]], a Roman god, and the Latin form of America.<ref>Gotch, A.T. (1995)</ref> It was originally described by [[Carolus Linnaeus]]<ref name="Davies"/> in his 18th-century work, [[Systema Naturae]] under its current binomial name.{{Citation needed|date=January 2009}} He identified specimens from [[Sergipe]], and [[Rio Grande do Norte]], [[Brazil]], in 1758.<ref name="Davies"/> They are from the family Rheidae, and the order [[Struthioniformes]], commonly known as [[ratite]]s. They are joined in this order by [[Emus|emu]], [[ostrich]]es, [[Cassowary|cassowaries]], [[moa]]s, and [[elephant bird]]s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Description== | ||

| + | [[Image:greater rhea in english wildlifepark arp.jpg|thumb|left|Greater Rhea closeup, [[Cricket St Thomas]] Wildlife Park (Somerset, England)]] | ||

| + | [[Image:RheaamericanaWeisslingHahn.JPG|thumb|left|[[Leucistic]] male, [[Tierpark Hellabrunn]]]] | ||

| + | The adults have an average weight of {{convert|20|-|27|kg|lb|abbr=on}} and {{Convert|129|cm|in|abbr=on}} long from beak to tail; they usually stand about 1.50 m (5 ft) tall. The males are generally bigger than the females, males can weigh up to {{Convert|40|kg|lb}} and measure over {{Convert|150|cm|in|abbr=on}} long.<ref name="Davies">Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)</ref><ref>McFie, H (2003)</ref><ref name = "Mercolli, C & Yanosky, A (2001)">Mercolli, C & Yanosky, A (2001)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The legs are long and strong, and have three toes. The wings of the American Rhea are rather long; the birds use them during running to maintain balance during tight turns. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Greater Rheas have a fluffy, tattered-looking plumage. The feathers are gray or brown, with high individual variation, In general, males are darker than females. Even in the wild – particularly in Argentina – [[leucistic]] individuals (with white body plumage and blue eyes) as well as [[albino]]s occur. Hatchling Greater Rheas are grey with dark lengthwise stripes.<ref name = jutglar,F1992>Jutglar, F (1992)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Subspecies=== | ||

| + | There are five [[subspecies]] of the Greater Rhea, which are difficult to distinguish and whose validity is somewhat unclear; their ranges meet around the [[Tropic of Capricorn]]:<ref name = jutglar,F1992 /> | ||

| + | * ''R. americana americana'' – campos of northern and eastern [[Brazil]]<ref name="Clements, J (2007)">Clements, J (2007)</ref>. | ||

| + | * ''R. americana intermedia'' – [[Uruguay]] and extreme southeastern [[Brazil]] ([[Rio Grande do Sul]] province)<ref name="Clements, J (2007)" />. | ||

| + | * ''R. americana nobilis'' – eastern [[Paraguay]], east of [[Rio Paraguay]]<ref name="Clements, J (2007)" />. | ||

| + | * ''R. americana araneipes'' – chaco of [[Paraguay]] and [[Bolivia]] and the [[Mato Grosso]] province of [[Brazil]]<ref name="Clements, J (2007)" />. | ||

| + | * ''R. americana albescens'' – plains of [[Argentina]] south to the [[Rio Negro Province|Rio Negro]] province.<ref name="Clements, J (2007)" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Main subspecific differences are the extent of the black coloring of the throat and the height. However, rheas differ so little across their range that without knowledge of the place of origin it is essentially impossible to identify captive birds to subspecies.<ref name = jutglar,F1992 /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Distribution, ecology and status== | ||

| + | The Greater Rhea is endemic to [[Argentina]], [[Bolivia]], [[Brazil]], [[Paraguay]] and [[Uruguay]]<ref name="Clements, J (2007)" />. This species inhabits grassland dominated e.g. by [[satintail]] (''Imperata'') and [[bahiagrass]] (''Paspalum'') species<ref name = "Mercolli, C & Yanosky, A (2001)" />, as well as [[savanna]], scrub forest, [[chaparral]], and even [[desert]] and [[palustrine]]<ref>Accordi, I & Barcellos, A (2006)</ref> lands, though it prefers areas with at least some tall vegetation. It is absent from the [[humid]] [[tropical]] forests of the [[Mata Atlântica]] and [[planalto]] uplands along the coast of Brazil<ref>Bencke, G (2007)</ref> and extends south to 40° [[latitude]]. During the breeding season (spring and summer), it stays near water. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A small population of the Greater Rhea has become established in [[Germany]]. Three pairs escaped from a farm in [[Groß Grönau]], [[Schleswig-Holstein]], in August 2000. These birds survived the winter and succeeded in breeding in habitat similar to that of their South American one. They eventually crossed the [[Wakenitz]] river and settled in [[Mecklenburg-Vorpommern]] in the area around and particularly to the north of [[Thandorf]] village.<ref>Schuh, H (2003)</ref> As of the late 2000s the population is estimated to be 7 birds and in 2001 18 birds. In October 2008 the population was estimated by two German scientists at around 100 birds (Korthals, A. & F. Philipp).<ref>International conference 'Invasive species - How we are prepared ? at the Brandenburgische Akademie „Schloss Criewen“, Criewen, Germany 2008</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | These rheas are legally protected in Germany in a similar way to native species. In its new home, the Greater Rhea is considered generally beneficial as its browsing helps maintain the [[habitat]] diversity of the sparsely-populated grasslands bordering the [[Schaalsee]] [[biosphere reserve]].<ref>Schuh (2003)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Food and predators=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Mercedes Cossio 2.jpg|thumb|right|Wild Greater Rhea (probably ''R. a. albescens'') in habitat. [[Goya Department]], [[Corrientes Province]], [[Argentina]]]] | ||

| + | The bulk of its food consists of broad-leaved [[dicot]] [[foliage]] and other plantstuffs, particularly [[seed]] and [[fruit]] when in season. Favorite food plants include native and introduced [[species]] from all sorts of dicot [[family (biology)|families]], such as [[Amaranthaceae]], [[Asteraceae]], [[Bignoniaceae]]<ref>E.g. [[Caribbean Trumpet Tree|"Caribbean" Trumpet Tree]] (''Tabebuia aurea''): Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006).</ref>, [[Brassicaceae]], [[Fabaceae]]<ref>E.g. [[Lebbeck]] (''Albizia lebbeck''), [[Añil]] (''Indigofera suffruticosa'') and ''[[Plathymenia foliolosa]]'', including seeds: Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006).</ref>, [[Lamiaceae]]<ref>E.g. Chan (''[[Hyptis suaveolens]]''): Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006).</ref>, [[Myrtaceae]]<ref>E.g. ''[[Eugenia dysenterica]]'' and ''[[Psidium cinereum]]'' fruit: Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006).</ref> or [[Solanaceae]]<ref>E.g. ''[[Solanum palinacanthum]]'' and [[Wolf Apple]] (''S. lycocarpum'') fruit: Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006).</ref>. [[Magnoliidae]] fruit, for example of ''[[Duguetia furfuracea]]'' ([[Annonaceae]]) or [[avocados]] (''Persea americana'', [[Lauraceae]]) can be seasonally important. They do not usually eat [[cereal]] grains, or [[monocots]] in general. However, the leaves of particular [[grass]] species like ''[[Brachiaria brizantha]]'' can be eaten in large quantities, and [[Liliaceae]] (e.g. the [[sarsaparilla]] ''[[Smilax brasiliensis]]'') have also been recorded as foodplants. Even tough and spiny vegetable matter like [[tuber]]s or [[thistle]]s is eaten with relish. Like many birds which feed on tough plant matter, the Greater Rhea swallows [[pebble]]s which help grind down the food for easy digestion. It is much attracted to sparkling objects and sometimes accidentally swallows metallic or glossy objects.<ref name = jutglar,F1992 /><ref name="Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006)">Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Nandu Ger.jpg|thumb|left|Feral Greater Rhea in [[cereal]] field in [[Mecklenburg-Vorpommern]], [[Germany]]. The species normally uses such [[monoculture]]s to hide rather to feed on the plants.]] | ||

| + | In [[field]]s and [[plantation]]s of plants they do not like to eat – e.g. [[cereal]]s or ''[[Eucalyptus]]'' – the Greater Rhea can be a species quite beneficial to farmers. It will eat any large [[invertebrate]] it can catch; its food includes [[locust]]s and [[grasshopper]]s, [[true bug]]s, [[cockroach]]es and other [[pest (organism)|pest]] [[insect]]s. Juveniles eat more animal matter than adults. In mixed ''[[cerrado]]'' and agricultural land in [[Minas Gerais]] (Brazil), ''R. a. americana'' was noted to be particularly fond of [[beetle]]s. It is not clear whether this applies to the species in general but for example in [[pampas]] habitat, beetle consumption is probably lower simply due to availability while [[Orthoptera]] might be more important. The Greater Rhea is able to eat [[Hymenoptera]] in quantity. These [[insect]]s contain among them many who can give painful [[insect sting|stings]], though the birds do not seem to mind. It may be that this species has elevated resistance to poison, as it readily eats [[scorpion]]s. But even small [[vertebrate]]s like [[rodent]]s, [[snake]]s, [[lizard]]s and small [[bird]]s are eaten. Sometimes, Greater Rheas will gather at [[carrion]] to feed on [[fly|flies]]; they are also known to eat dead or dying [[fish]] in the dry season, but as vertebrate prey in general not in large quantities.<ref name = jutglar,F1992 /><ref name = "Schetini de Azevedo ''et al.'' (2006)" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The natural [[predator]]s of adult Greater Rheas are limited to the [[Cougar]] (''Puma concolor'') and the [[Jaguar]] (''Panthera onca''). [[feral|Feral dog]]s are known to kill younger birds, and the [[Southern Caracara]] (''Caracara plancus'') is suspected to prey on hatchlings. [[Armadillo]]s sometimes feed on Greater Rhea eggs; nests have been found which had been undermined by a [[Six-banded Armadillo]] (''Euphractus sexcinctus'') or a [[Big Hairy Armadillo]] (''Chaetophractus villosus'') and the rhea eggs were broken apart.<ref name = "Mercolli, C & Yanosky, A (2001)" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Captive-bred Greater Rheas exhibit significant [[ecological naïvete]]. This fearlessness renders them highly vulnerable to predators if the birds are released into the wild in [[reintroduction]] projects. [[Classical conditioning]] of Greater Rhea juveniles against predator models can prevent this to some degree, but the [[personality type]] of the birds – whether they are bold or shy – influences the success of such training. In 2006, a protocol was established for training Greater Rheas to avoid would-be predators, and for identifying the most cautious animals for release.<ref>de Azevedo, C & Young, R (2006)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Reproduction=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Baby Rhea americana.JPG|thumb|right|upright|A two-month old Greater Rhea in [[Tierpark Hagenbeck]] with hatchling at its feet]] | ||

| + | Greater Rheas breed in the warmer months, between August and January depending on the climate. Males are simultaneously [[polygynous]], females are serially [[polyandrous]]. In practice, this means that the females move around during breeding season, mating with a male and depositing their eggs with the male before leaving him and mating with another male. Males on the other hand are sedentary, attending the nests and taking care of incubation and the hatchlings all on their own. Although recent evidence suggest that dominant males may enlist a subordinate male to roost for him while he starts a second nest with a second harem.<ref name="Davies" /> The nests are thus collectively used by several females and can contain as many as 80 [[egg (biology)|eggs]] laid by a dozen females; each individual female's [[clutch (eggs)|clutch]] numbers some 5-10 eggs.<ref name = jutglar,F1992 /> However, the average clutch size is 26 with 7 different females eggs.<ref name="Davies" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rhea eggs measure about {{Convert|130|x|90|mm|in|abbr=on}} and weigh {{Convert|600|g|oz|abbr=on}} on average; they are thus less than half the size of an [[ostrich]] egg. Their shell is greenish-yellow when fresh but soon fades to dull cream when exposed to light. The nest is a simple shallow and wide scrape in a hidden location; males will drag sticks, grass, and leaves in the area surrounding the nest so it resembles a firebrak as wide as their neck can reach. | ||

| + | The incubation period is 29–43 days. All the eggs hatch within 36 hours of each other even though the eggs in one nest were laid perhaps as much as two weeks apart.<ref name="Davies" /> As it seems, when the first young are ready to hatch they start a call resemebling a pop-bottle rocket, even while still inside the egg, thus the hatching time is coordinated. Greater Rheas are half-grown about three months after hatching, and sexually mature by their 14th month. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Conservation status=== | ||

| + | The Greater Rhea is considered a [[Near Threatened]] species according to the [[IUCN]]. The species is believed to be declining but it is still reasonably plentiful across its wide range,<ref name = "IUCN" /> which is about {{convert|6540000|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}}. The major factors in its decline is ranching and farming.<ref>BirdLife International (2008)(a)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Farmers sometimes consider them pests, because they will eat broad-leaved crop plants, such as [[cabbage]], [[chard]] and [[bok choi]], although if very hungry, [[soybean]] leaves will do. Rheas disdain [[grass]]es unless there are no other options. Where they occur as [[pest (organism)|pest]]s, farmers tend to hunt and kill Greater Rheas. This, along with egg-gathering and [[habitat loss]], has led to the population decline. The habitual burning of crops in [[South America]] has also contributed to their decline. Moreover, the birds' health is affected by wholesale [[pesticide]] and [[herbicide]] spraying; while not threatening on a large scale, locally the species may be seriously affected by poisoning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | International trade in wild-caught Greater Rheas is restricted as per [[CITES]] Appendix II. The populations of [[Argentina]] and [[Uruguay]] are most seriously affected by the decline, in the former country mostly due to the adverse impact of agriculture, in the latter mostly due to overhunting in the late 20th century.<ref name="IUCN" /><ref name = jutglar,F1992 /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Rhea farming== | ||

| + | This species is farmed in [[North America]] and [[Europe]] similar to the [[Emu]] and [[Ostrich]]. The main products are [[meat]] and [[egg (food)|eggs]], but [[rhea oil]] is used for cosmetics and soaps and rhea [[leather]] is also traded in quantity. Male Greater Rheas are very territorial during the breeding season. The infant chicks have high mortality in typical confinement farming situations, but under optimum free-range conditions chicks will reach adult size by their fifth month. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Footnotes== | ||

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * '''Accordi''', Iury Almeida & Barcellos, André (2006): Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul [Bird composition and conservation in eight wetlands of the hidrographic basin of Guaíba lake, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. ''Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia'' '''14'''(2): 101-115 [Portuguese with English abstract]. | ||

| + | * '''Bencke''', Glayson Ariel (2007): Avifauna atual do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: aspectos biogeográficos e distribucionais ["The Recent avifauna of Rio Grande do Sul: Biogeographical and distributional aspects"]. Talk held on 2007-JUN-22 at ''Quaternário do RS: integrando conhecimento'', Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. | ||

| + | * {{IUCN2006|assessors=BirdLife International|year=2008|id=141086|title=Rhea americana|downloaded=04 Feb 2009}} | ||

| + | * {{cite web| url=http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/index.html?action=SpcHTMDetails.asp&sid=2&m=0 | title=Greater Rhea - BirdLife Species Factsheet | accessdate=06 Feb 2009 | author=BirdLife International | year=2008(a)| work=Data Zone}} | ||

| + | * {{cite web| url= http://www.taxonomy.nl/Main/Classification/51258.htm| title=Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Rhea americana | accessdate=Feb 04 2009 | last='''Brands''' | first=Sheila | authorlink= | date=August 14, 2008 | work=Project: The Taxonomicon }} | ||

| + | * {{cite book |last1='''Clements''' |first1=James |title=The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World |edition=6 |year=2007 |publisher= Cornell University Press|location=Ithaca, NY |isbn=978 0 8014 4501 9 }} | ||

| + | * {{cite encyclopedia |last='''Davies''' |first=S.J.J.F.|editor1-first=Michael |editor1-last= Hutchins|encyclopedia=Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia |title=Rheas |edition=2 |year=2003 |publisher=Gale Group|volume=8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins |location=Farmington Hills, MI|isbn=0 7876 5784 0 |pages=69–73}} | ||

| + | * '''de Azevedo''', Cristiano S. & Young, Robert J. (2006): Shyness and boldness in greater rheas ''Rhea americana'' Linnaeus (Rheiformes, Rheidae): the effects of antipredator training on the personality of the birds. ''Revista Brasileira de Zoologia'' '''23'''(1): 202–210 [English with Portuguese abstract]. <small>{{doi|10.1590/S0101-81752006000100012}}</small> | ||

| + | * {{cite book |last1='''Gotch''' |first1=A.F. |title=Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals|year= 1995 |origyear=1979 |publisher=Facts on File|location=New York, NY|isbn=0 8160 3377 3|page=177|chapter=Rheas}} | ||

| + | * '''Jutglar''', Francesc (1992): Family Rheidae (Rheas). ''In:'' {{aut|del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.)}}: ''[[Handbook of Birds of the World]]'' (Vol.1: Ostrich to Ducks): 84-89, Plate 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. <small>ISBN 84-87334-10-5</small> | ||

| + | * '''Mercolli''', Claudia & Yanosky, A. Alberto (2001): Greater rhea predation in the Eastern Chaco of Argentina. ''Ararajuba'' '''9'''(2): 139-141. | ||

| + | * '''McFie''', Hubert (2003): ACountryLife.Com – [http://www.acountrylife.com/page.php?id=64 Something Rheally Interesting]. | ||

| + | * '''Schetini de Azevedo''', Cristiano; Penha Tinoco, Herlandes; Bosco Ferraz, João & Young, Robert John (2006): The fishing rhea: a new food item in the diet of wild greater rheas (''Rhea americana'', Rheidae, Aves). ''Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia'' '''14'''(3): 285-287 [English with Portuguese abstract]. | ||

| + | * '''Schuh''', Hans (2003): [http://www.zeit.de/2003/13/Nandu Alleinerziehender Asylant] ["Single-parent asylum seeker"]. ''[[Die Zeit]]'', 2003-MAR-20 [in German, [http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=http://www.zeit.de/2003/13/Nandu&sa=X&oi=translate&resnum=4&ct=result&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dwakenitz%2Brhea%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DN Google translation] ]. | ||

| + | * {{cite web| url= http://www.taxonomy.nl/Main/Classification/51258.htm| title=Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Order Tinamiformes | accessdate=Feb 04 2009 | last='''Brands''' | first=Sheila | authorlink= | date=August 14, 2008 | work=Project: The Taxonomicon }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | {{Commons category|Rhea americana}} | ||

| + | * {{aut|Accordi, Iury Almeida & Barcellos, André}} (2006): Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul [Bird composition and conservation in eight wetlands of the hidrographic basin of Guaíba lake, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. ''Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia'' '''14'''(2): 101-115 [Portuguese with English abstract]. [http://www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/artigos/Volume142/ara142art2.pdf PDf fulltext] | ||

| + | * {{aut|Bencke, Glayson Ariel}} (2007): Avifauna atual do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: aspectos biogeográficos e distribucionais ["The Recent avifauna of Rio Grande do Sul: Biogeographical and distributional aspects"]. Talk held on 2007-JUN-22 at ''Quaternário do RS: integrando conhecimento'', Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. [http://www6.ufrgs.br/alpp/Resumos_Quaternario_RS.pdf PDF abstract] | ||

| + | * {{IUCN2008|assessors={{aut|[[BirdLife International]] (BLI)}}|year=2008|id=141086|title=Rhea americana|downloaded=05 November 2008}} | ||

| + | * {{aut|de Azevedo, Cristiano S. & Young, Robert J.}} (2006): Shyness and boldness in greater rheas ''Rhea americana'' Linnaeus (Rheiformes, Rheidae): the effects of antipredator training on the personality of the birds. ''Revista Brasileira de Zoologia'' '''23'''(1): 202–210 [English with Portuguese abstract]. <small>{{doi|10.1590/S0101-81752006000100012}}</small> [http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbzool/v23n1/a12v23n1.pdf PDF fulltext] | ||

| + | * {{aut|Jutglar, Francesc}} (1992): Family Rheidae (Rheas). ''In:'' {{aut|del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.)}}: ''[[Handbook of Birds of the World]]'' (Vol.1: Ostrich to Ducks): 84-89, Plate 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. <small>ISBN 84-87334-10-5</small> | ||

| + | * {{aut|Mercolli, Claudia & Yanosky, A. Alberto}} (2001): Greater rhea predation in the Eastern Chaco of Argentina. ''Ararajuba'' '''9'''(2): 139-141. [http://www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/artigos/Volume92/ara92art7.pdf PDF fulltext] | ||

| + | * {{aut|McFie, Hubert}} (2003): ACountryLife.Com – [http://www.acountrylife.com/page.php?id=64 Something Rheally Interesting]. | ||

| + | * {{aut|Schetini de Azevedo, Cristiano; Penha Tinoco, Herlandes; Bosco Ferraz, João & Young, Robert John}} (2006): The fishing rhea: a new food item in the diet of wild greater rheas (''Rhea americana'', Rheidae, Aves). ''Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia'' '''14'''(3): 285-287 [English with Portuguese abstract]. [http://www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/artigos/Volume143/ara143not3.pdf PDF fulltext] | ||

| + | * {{aut|Schuh, Hans}} (2003): [http://www.zeit.de/2003/13/Nandu Alleinerziehender Asylant] ["Single-parent asylum seeker"]. ''[[Die Zeit]]'', 2003-MAR-20 [in German, [http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=de&u=http://www.zeit.de/2003/13/Nandu&sa=X&oi=translate&resnum=4&ct=result&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dwakenitz%2Brhea%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DN Google translation] ]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | *[http://ibc.lynxeds.com/family/rheas-rheidae Rhea videos, photos and sounds] on the Internet Bird Collection | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

| Line 81: | Line 208: | ||

[[Category:Birds]] | [[Category:Birds]] | ||

| − | {{credit|Rhea_(bird)&oldid=343314494}} | + | {{credit|Rhea_(bird)&oldid=343314494|Greater_Rhea&oldid=344833542}} |

Revision as of 15:25, 22 February 2010

| Rhea

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

American Rhea, Rhea americana

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

The rheas are ratites (flightless birds, with unkeeled sterna) in the genus Rhea, native to South America. There are two existing species: the Greater or American Rhea and the Lesser or Darwin's Rhea. The genus name was given in 1752 by Paul Möhring and adopted as the English common name. Möhring's reason for choosing this name, from the Rhea of classical mythology, is not known.

Description

Rheas are large, flightless birds with gray-brown plumage, long legs and long necks, similar to an ostrich. These birds can reach 5.6 feet (1.7 m), and weigh up to 88 pounds (40 kg).[2][3] Their wings are large for a flightless bird and are spread while running, to act like sails.[4] Unlike most birds, rheas have only three toes. Their tarsus has horizontal plates on the front of it. They also store urine separately in an expansion of the cloaca.[3]

Taxonomy

The recognized extant species are:

- Greater Rhea Rhea americana

- R. a. americana, found in campos of northern and eastern Brazil.[5]

- R. a. intermedia, southeastern Brazil in Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay.[5]

- R. a. nobilis, eastern Paraguay, east of Rio Paraguay.[5]

- R. a. araneipes, chaco of Paraguay to Bolivia and Mato Grosso in Brazil.[5]

- R. a. albescens, plains of Argentina south to Rio Negro.[5]

- Lesser Rhea Rhea pennata

Rhea pennata was not always in the Rhea genus. In 2008 the SACC, the last holdout, approved the merging of the genera, Rhea and Pterocnemia on August 7, 2008. This merging of genera leaves only the Rhea genus.[6] A third species of rhea, Rhea nana, was described by Lydekker in 1894 based on a single egg found in Patagonia,[7] but today no major authorities consider it valid.

Behavior

Individual and flocking

Rheas tend to be silent birds with the exception being when they are chicks or when the male is seeking a mate. During the non-breeding season they may form flocks of between 10 and 100 birds, although the lesser rhea forms smaller flocks than this. When in danger they flee in a zig-zag course, utilizing first one wing then the other, similar to a rudder. During breeding season the flocks break up.[3]

Diet

They are omnivorous and prefer to eat broad-leafed plants, but also eat seeds, roots, fruit, lizards, beetles, grasshoppers, and carrion.[3]

Reproduction

Rheas are polygamous, with males courting between two and twelve females. After mating, the male builds a nest, in which each female lays her eggs in turn. The nest consists of a simple scrape in the ground, lined with grass and leaves.[4] The male incubates from ten to sixty eggs. The male will utilize a decoy system and place some eggs outside the nest and sacrifice these to predators, so that they won't attempt to get inside the nest. The male may utilize another subordinate male to incubate his eggs, while he finds another harem to start a second nest.[3] The chicks hatch within 36 hours of each other. The females, meanwhile, may move on and mate with other males. While caring for the young, the males will charge at any perceived threat that approach the chicks including female rheas and humans. The young reach full adult size in about six months but do not breed until they reach two years of age.[4]

Human interaction

Rheas have many uses in South America. Feathers are used for feather dusters, skins are used for cloaks or leather, and their meat is a staple to many people.[3]

Greater or American Rhea

| Greater Rhea | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Rhea americana (Linnaeus, 1758)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

Distribution of subspecies

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

R. americana americana (Linnaeus, 1758)[1] |

The Greater Rhea (Rhea americana) is also known as the Grey, Common or American Rhea. The native range of this flightless bird is the eastern part of South America; it is not only the largest species of the genus Rhea but also the largest American bird alive. It is also notable for its reproductive habits, and for the fact that a group has established itself in Germany in recent years. In its native range, it is known as ñandú (Spanish) or ema (Portuguese).

Taxonomy

The Greater Rhea, Rhea americana, derives its name from Rhea, a Roman god, and the Latin form of America.[9] It was originally described by Carolus Linnaeus[3] in his 18th-century work, Systema Naturae under its current binomial name.[citation needed] He identified specimens from Sergipe, and Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in 1758.[3] They are from the family Rheidae, and the order Struthioniformes, commonly known as ratites. They are joined in this order by emu, ostriches, cassowaries, moas, and elephant birds.

Description

The adults have an average weight of 20–27 kg (44–60 lb) and 129 cm (51 in) long from beak to tail; they usually stand about 1.50 m (5 ft) tall. The males are generally bigger than the females, males can weigh up to 40 kilograms (88 lb) and measure over 150 cm (59 in) long.[3][10][11]

The legs are long and strong, and have three toes. The wings of the American Rhea are rather long; the birds use them during running to maintain balance during tight turns.

Greater Rheas have a fluffy, tattered-looking plumage. The feathers are gray or brown, with high individual variation, In general, males are darker than females. Even in the wild – particularly in Argentina – leucistic individuals (with white body plumage and blue eyes) as well as albinos occur. Hatchling Greater Rheas are grey with dark lengthwise stripes.[12]

Subspecies

There are five subspecies of the Greater Rhea, which are difficult to distinguish and whose validity is somewhat unclear; their ranges meet around the Tropic of Capricorn:[12]

- R. americana americana – campos of northern and eastern Brazil[13].

- R. americana intermedia – Uruguay and extreme southeastern Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul province)[13].

- R. americana nobilis – eastern Paraguay, east of Rio Paraguay[13].

- R. americana araneipes – chaco of Paraguay and Bolivia and the Mato Grosso province of Brazil[13].

- R. americana albescens – plains of Argentina south to the Rio Negro province.[13]

Main subspecific differences are the extent of the black coloring of the throat and the height. However, rheas differ so little across their range that without knowledge of the place of origin it is essentially impossible to identify captive birds to subspecies.[12]

Distribution, ecology and status

The Greater Rhea is endemic to Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay[13]. This species inhabits grassland dominated e.g. by satintail (Imperata) and bahiagrass (Paspalum) species[11], as well as savanna, scrub forest, chaparral, and even desert and palustrine[14] lands, though it prefers areas with at least some tall vegetation. It is absent from the humid tropical forests of the Mata Atlântica and planalto uplands along the coast of Brazil[15] and extends south to 40° latitude. During the breeding season (spring and summer), it stays near water.

A small population of the Greater Rhea has become established in Germany. Three pairs escaped from a farm in Groß Grönau, Schleswig-Holstein, in August 2000. These birds survived the winter and succeeded in breeding in habitat similar to that of their South American one. They eventually crossed the Wakenitz river and settled in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern in the area around and particularly to the north of Thandorf village.[16] As of the late 2000s the population is estimated to be 7 birds and in 2001 18 birds. In October 2008 the population was estimated by two German scientists at around 100 birds (Korthals, A. & F. Philipp).[17]

These rheas are legally protected in Germany in a similar way to native species. In its new home, the Greater Rhea is considered generally beneficial as its browsing helps maintain the habitat diversity of the sparsely-populated grasslands bordering the Schaalsee biosphere reserve.[18]

Food and predators

The bulk of its food consists of broad-leaved dicot foliage and other plantstuffs, particularly seed and fruit when in season. Favorite food plants include native and introduced species from all sorts of dicot families, such as Amaranthaceae, Asteraceae, Bignoniaceae[19], Brassicaceae, Fabaceae[20], Lamiaceae[21], Myrtaceae[22] or Solanaceae[23]. Magnoliidae fruit, for example of Duguetia furfuracea (Annonaceae) or avocados (Persea americana, Lauraceae) can be seasonally important. They do not usually eat cereal grains, or monocots in general. However, the leaves of particular grass species like Brachiaria brizantha can be eaten in large quantities, and Liliaceae (e.g. the sarsaparilla Smilax brasiliensis) have also been recorded as foodplants. Even tough and spiny vegetable matter like tubers or thistles is eaten with relish. Like many birds which feed on tough plant matter, the Greater Rhea swallows pebbles which help grind down the food for easy digestion. It is much attracted to sparkling objects and sometimes accidentally swallows metallic or glossy objects.[12][24]

In fields and plantations of plants they do not like to eat – e.g. cereals or Eucalyptus – the Greater Rhea can be a species quite beneficial to farmers. It will eat any large invertebrate it can catch; its food includes locusts and grasshoppers, true bugs, cockroaches and other pest insects. Juveniles eat more animal matter than adults. In mixed cerrado and agricultural land in Minas Gerais (Brazil), R. a. americana was noted to be particularly fond of beetles. It is not clear whether this applies to the species in general but for example in pampas habitat, beetle consumption is probably lower simply due to availability while Orthoptera might be more important. The Greater Rhea is able to eat Hymenoptera in quantity. These insects contain among them many who can give painful stings, though the birds do not seem to mind. It may be that this species has elevated resistance to poison, as it readily eats scorpions. But even small vertebrates like rodents, snakes, lizards and small birds are eaten. Sometimes, Greater Rheas will gather at carrion to feed on flies; they are also known to eat dead or dying fish in the dry season, but as vertebrate prey in general not in large quantities.[12][24]

The natural predators of adult Greater Rheas are limited to the Cougar (Puma concolor) and the Jaguar (Panthera onca). Feral dogs are known to kill younger birds, and the Southern Caracara (Caracara plancus) is suspected to prey on hatchlings. Armadillos sometimes feed on Greater Rhea eggs; nests have been found which had been undermined by a Six-banded Armadillo (Euphractus sexcinctus) or a Big Hairy Armadillo (Chaetophractus villosus) and the rhea eggs were broken apart.[11]

Captive-bred Greater Rheas exhibit significant ecological naïvete. This fearlessness renders them highly vulnerable to predators if the birds are released into the wild in reintroduction projects. Classical conditioning of Greater Rhea juveniles against predator models can prevent this to some degree, but the personality type of the birds – whether they are bold or shy – influences the success of such training. In 2006, a protocol was established for training Greater Rheas to avoid would-be predators, and for identifying the most cautious animals for release.[25]

Reproduction

Greater Rheas breed in the warmer months, between August and January depending on the climate. Males are simultaneously polygynous, females are serially polyandrous. In practice, this means that the females move around during breeding season, mating with a male and depositing their eggs with the male before leaving him and mating with another male. Males on the other hand are sedentary, attending the nests and taking care of incubation and the hatchlings all on their own. Although recent evidence suggest that dominant males may enlist a subordinate male to roost for him while he starts a second nest with a second harem.[3] The nests are thus collectively used by several females and can contain as many as 80 eggs laid by a dozen females; each individual female's clutch numbers some 5-10 eggs.[12] However, the average clutch size is 26 with 7 different females eggs.[3]

Rhea eggs measure about 130 mm × 90 mm (5.1 in × 3.5 in)

and weigh 600 g (21 oz) on average; they are thus less than half the size of an ostrich egg. Their shell is greenish-yellow when fresh but soon fades to dull cream when exposed to light. The nest is a simple shallow and wide scrape in a hidden location; males will drag sticks, grass, and leaves in the area surrounding the nest so it resembles a firebrak as wide as their neck can reach.

The incubation period is 29–43 days. All the eggs hatch within 36 hours of each other even though the eggs in one nest were laid perhaps as much as two weeks apart.[3] As it seems, when the first young are ready to hatch they start a call resemebling a pop-bottle rocket, even while still inside the egg, thus the hatching time is coordinated. Greater Rheas are half-grown about three months after hatching, and sexually mature by their 14th month.

Conservation status

The Greater Rhea is considered a Near Threatened species according to the IUCN. The species is believed to be declining but it is still reasonably plentiful across its wide range,[8] which is about 6,540,000 km² (2,530,000 sq mi). The major factors in its decline is ranching and farming.[26]

Farmers sometimes consider them pests, because they will eat broad-leaved crop plants, such as cabbage, chard and bok choi, although if very hungry, soybean leaves will do. Rheas disdain grasses unless there are no other options. Where they occur as pests, farmers tend to hunt and kill Greater Rheas. This, along with egg-gathering and habitat loss, has led to the population decline. The habitual burning of crops in South America has also contributed to their decline. Moreover, the birds' health is affected by wholesale pesticide and herbicide spraying; while not threatening on a large scale, locally the species may be seriously affected by poisoning.

International trade in wild-caught Greater Rheas is restricted as per CITES Appendix II. The populations of Argentina and Uruguay are most seriously affected by the decline, in the former country mostly due to the adverse impact of agriculture, in the latter mostly due to overhunting in the late 20th century.[8][12]

Rhea farming

This species is farmed in North America and Europe similar to the Emu and Ostrich. The main products are meat and eggs, but rhea oil is used for cosmetics and soaps and rhea leather is also traded in quantity. Male Greater Rheas are very territorial during the breeding season. The infant chicks have high mortality in typical confinement farming situations, but under optimum free-range conditions chicks will reach adult size by their fifth month.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Brands, S. (2008)

- ↑ An introduction to study of birds

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Davies, S.J.J.F. (1991)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Clements, J. (2007)

- ↑ Remsen, Jr., J. V. (2008)

- ↑ Knox & Walters (1994)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 BirdLife International(2009)

- ↑ Gotch, A.T. (1995)

- ↑ McFie, H (2003)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mercolli, C & Yanosky, A (2001)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Jutglar, F (1992)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Clements, J (2007)

- ↑ Accordi, I & Barcellos, A (2006)

- ↑ Bencke, G (2007)

- ↑ Schuh, H (2003)

- ↑ International conference 'Invasive species - How we are prepared ? at the Brandenburgische Akademie „Schloss Criewen“, Criewen, Germany 2008

- ↑ Schuh (2003)

- ↑ E.g. "Caribbean" Trumpet Tree (Tabebuia aurea): Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006).

- ↑ E.g. Lebbeck (Albizia lebbeck), Añil (Indigofera suffruticosa) and Plathymenia foliolosa, including seeds: Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006).

- ↑ E.g. Chan (Hyptis suaveolens): Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006).

- ↑ E.g. Eugenia dysenterica and Psidium cinereum fruit: Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006).

- ↑ E.g. Solanum palinacanthum and Wolf Apple (S. lycocarpum) fruit: Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Schetini de Azevedo et al. (2006)

- ↑ de Azevedo, C & Young, R (2006)

- ↑ BirdLife International (2008)(a)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Accordi, Iury Almeida & Barcellos, André (2006): Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul [Bird composition and conservation in eight wetlands of the hidrographic basin of Guaíba lake, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 14(2): 101-115 [Portuguese with English abstract].

- Bencke, Glayson Ariel (2007): Avifauna atual do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: aspectos biogeográficos e distribucionais ["The Recent avifauna of Rio Grande do Sul: Biogeographical and distributional aspects"]. Talk held on 2007-JUN-22 at Quaternário do RS: integrando conhecimento, Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

- BirdLife International 2008. [1]. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species., World Conservation Union. Retrieved on 04 Feb 2009.

- BirdLife International (2008(a)). Greater Rhea - BirdLife Species Factsheet. Data Zone. Retrieved 06 Feb 2009.

- Brands, Sheila (August 14, 2008). Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Rhea americana. Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 04 2009.

- (2007) The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World, 6, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978 0 8014 4501 9.

- Davies, S.J.J.F.. (2003). "Rheas". Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia (2) 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins: 69–73. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- de Azevedo, Cristiano S. & Young, Robert J. (2006): Shyness and boldness in greater rheas Rhea americana Linnaeus (Rheiformes, Rheidae): the effects of antipredator training on the personality of the birds. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 23(1): 202–210 [English with Portuguese abstract]. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1590/S0101-81752006000100012

- [1979] (1995) "Rheas", Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. ISBN 0 8160 3377 3.

- Jutglar, Francesc (1992): Family Rheidae (Rheas). In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.): Handbook of Birds of the World (Vol.1: Ostrich to Ducks): 84-89, Plate 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-10-5

- Mercolli, Claudia & Yanosky, A. Alberto (2001): Greater rhea predation in the Eastern Chaco of Argentina. Ararajuba 9(2): 139-141.

- McFie, Hubert (2003): ACountryLife.Com – Something Rheally Interesting.

- Schetini de Azevedo, Cristiano; Penha Tinoco, Herlandes; Bosco Ferraz, João & Young, Robert John (2006): The fishing rhea: a new food item in the diet of wild greater rheas (Rhea americana, Rheidae, Aves). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 14(3): 285-287 [English with Portuguese abstract].

- Schuh, Hans (2003): Alleinerziehender Asylant ["Single-parent asylum seeker"]. Die Zeit, 2003-MAR-20 [in German, Google translation ].

- Brands, Sheila (August 14, 2008). Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Order Tinamiformes. Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 04 2009.

Further reading

- Accordi, Iury Almeida & Barcellos, André (2006): Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul [Bird composition and conservation in eight wetlands of the hidrographic basin of Guaíba lake, State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 14(2): 101-115 [Portuguese with English abstract]. PDf fulltext

- Bencke, Glayson Ariel (2007): Avifauna atual do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil: aspectos biogeográficos e distribucionais ["The Recent avifauna of Rio Grande do Sul: Biogeographical and distributional aspects"]. Talk held on 2007-JUN-22 at Quaternário do RS: integrando conhecimento, Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. PDF abstract

- BirdLife International (BLI) (2008). Rhea americana. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 05 November 2008.

- de Azevedo, Cristiano S. & Young, Robert J. (2006): Shyness and boldness in greater rheas Rhea americana Linnaeus (Rheiformes, Rheidae): the effects of antipredator training on the personality of the birds. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 23(1): 202–210 [English with Portuguese abstract]. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1590/S0101-81752006000100012 PDF fulltext

- Jutglar, Francesc (1992): Family Rheidae (Rheas). In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.): Handbook of Birds of the World (Vol.1: Ostrich to Ducks): 84-89, Plate 2. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-10-5

- Mercolli, Claudia & Yanosky, A. Alberto (2001): Greater rhea predation in the Eastern Chaco of Argentina. Ararajuba 9(2): 139-141. PDF fulltext

- McFie, Hubert (2003): ACountryLife.Com – Something Rheally Interesting.

- Schetini de Azevedo, Cristiano; Penha Tinoco, Herlandes; Bosco Ferraz, João & Young, Robert John (2006): The fishing rhea: a new food item in the diet of wild greater rheas (Rhea americana, Rheidae, Aves). Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 14(3): 285-287 [English with Portuguese abstract]. PDF fulltext

- Schuh, Hans (2003): Alleinerziehender Asylant ["Single-parent asylum seeker"]. Die Zeit, 2003-MAR-20 [in German, Google translation ].

External links

- Rhea videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

Footnotes

References

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14 2008). Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Family Rheidae. Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 04 2009.

- (2007) The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World, 6, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978 0 8014 4501 9.

- Davies, S.J.J.F.. (2003). "Rheas". Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia (2) 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins: 69–71. Ed. Hutchins, Michael. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (1991). in Forshaw, Joseph: Encyclopaedia of Animals: Birds. London: Merehurst Press, 47–48. ISBN 1-85391-186-0.

- (1994) Extinct and Endangered Birds in the Collections of the Natural History Museum, British Ornithologists' Club Occasional Publications. British Ornithologists' Club.

- (1835) An introduction to study of birds. London, UK: Chiswick.

- Remsen Jr., J. V.; et al. (07 Aug 2008). Classification of birds of South America Part 01:. South American Classification Committee. American Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 04 Feb 2009.

External links

- Rhea videos on the Internet Bird Collection

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.