Poor Man's Bible

The term Poor Man's Bible refers to various forms of Christian art (paintings, carvings, mosaics, and stained glass) that were used primarily in churches and cathedrals to illustrate the teachings of the Bible. These art forms were very popular in the Middle Ages and were intended to educate the largely illiterate population about Christianity. In some churches, a single window was used as a Poor Man's Bible, while in others, the entire church was decorated with a complex biblical narrative that was intended to convey biblical lessons.

Until the invention of the Printing press in 1439, the average Christian living in Medieval Europe did not have access to a personal copy of the Bible; rather Bibles were copied by hand and reserved only for religious authorities. Nevertheless, to facilitate religious devotion and education among the masses, various forms of art were used in churches to teaches biblical stories and motifs. These forms of art became known as a Boor Man's Bible.

However, the term Poor Man's Bible is not to be confused with the so-called Biblia Pauperum, which are biblical picture books, either in illuminated manuscript or printed "block-book" form. The illuminated Biblia Pauperum, despite the name given in the 1930s by German scholars, were much too expensive to have been owned by the poor, although the printed versions were much cheaper and many were probably shown to the poor for instruction. However, the books, at least in their earlier manuscript versions, were created for the rich. In contrast, the carvings and stained glass windows of a churches provided free instruction to all whom entered their doors.

Types

Mural

A mural is a painting found on the surface of a plastered wall, the term coming from the Latin, muralis. Much cheaper than stained glass, murals can be extremely durable under good conditions, but liable to be damaged by damp conditions or candle smoke. Narrative murals are generally located on the upper walls of churches, while the lower walls may be painted to look like marble or drapery. They also occur on arches, vaulted roofs, and domes.

Murals were a common form of wall decoration in ancient Rome. The earliest Christian mural paintings come from the catacombs of Rome. They include many representations of Christ as the Good Shepherd, generally as a standardized image of a young, beardless man with a sheep on his shoulders. Other popular subjects include the Madonna and Child, Jonah being thrown into the sea, the three young men in the furnace and the Last Supper. Mural painting was to become a common form of enlightening decoration in Christian churches. Biblical themes rendered in mural can be found all over the Christian world, especially in areas where the Orthodox Church prevails. In Romania, there is an unusual group of churches in which it is the exterior rather than the interior which is richly decorated, the large arcaded porches containing images of the Last Judgement.[1]

Mural painting was also common in Italy, where the method employed was generally fresco, painting on freshly-laid, slightly damp plaster. Many fine examples have survived from the Medieval and Early Renaissance periods. Remarkably, the best known example of such Biblical story-telling was not created for the edification of the poor but for the rich and powerful, the Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel created by Michelangelo for Pope Julius II.

Mosaic

Mosaic is the art of decorating solid surfaces with pieces of multi-coloured stone or glass set in mortar. Golden mosaic can be created by applying gold leaf to a single surface of a transparent glass tile, and placing the gilt inwards towards the mortar so that it is visible but cannot be scraped. The gilt tiles are often used as a background to figures, giving a glowing and sumptuous effect. Mosaic can be applied equally well to flat or curved surfaces and is often used to decorate vaults and domes. In churches where mosaic is applied extensively, it gives an impression that the interior of the church has been spread with a blanket of pictures and patterns.[2]

Mosaic was a common form of decoration throughout the Roman Empire and because of its durability was usually applied to floors, where it was at first executed in pebbles or small marble tiles. During the Early Christian period glass tiles were used extensively for wall and vault decorations, the vault of the Mausoleum of Santa Costanza in Rome being a fine example of decorative, non-narrative Christian mosaic. A perhaps unique example of Late Roman pictorial mosaic is the magnificent apsidal mosaic of the Church of Santa Pudenziana. The nearby church, dedicated to her sister Santa Prassede, has mosaics which are Byzantine in style.[3]

Mosaic was a favorite form of decoration in the Byzantine period and richly decorated churches in this style can be seen throughout Greece, in Turkey, Italy, Sicily, Russia, and other countries. In the 19th century, gold mosaics were applied to the domes of the chancel of St Pauls Cathedral in London, illustrating the creation.[4] In Western Europe, however, it was rare north of the alps, with notable exceptions in Prague and Aachen.

Stone

Sculpture in stone is seemingly the most permanent way of creating images. Because stone is durable to the weather, it is the favored way of adding figurative decoration to the exteriors of church buildings, either with free-standing statues, figures that form a structural part of the building, or panels of pictorial reliefs. Unfortunately, with the pollution and acid rain of the 19th and 20th centuries, much architectural sculpture that had remained reasonably intact for centuries has rapidly deteriorated and become unrecognizable in the last 150 years. On the other hand, much sculpture that is located within church buildings is as fresh as the day it was carved. Because it is often made of the very substance of the building which houses it, narrative stone sculpture is often found internally to be decorating features such as capitals, or as figures located within the apertures of stone screens.

The first Christian sculpture took the form of sarcophagi, or stone coffins, modelled on those of non-Christian Romans which were often pictorially decorated. Hence, on Christian sarcophagi there were often small narrative panels, or images of Christ enthroned and surrounded by Saints. In Byzantine Italy, the application of stone reliefs of this nature spread to cathedra (bishop's thrones), ambo (reading lecterns), well heads, baldachin (canopy over altar) and other objects within the church, where it often took on symbolic form such as paired doves drinking from a chalice. Capitals of columns tended to be decorative, rather than narrative. It was in Western Europe, Northern France in particular, that sculptural narrative reached great heights in the Romanesque and Gothic periods, decorating, in particular, the great West Fronts of the cathedrals, the style spreading from there to other countries of Europe. In England, figurative architectural decoration most frequently was located in vast screens of niches across the West Front. Unfortunately, like the frescoes and windows, they were decimated in the Reformation.[5]

Stained glass

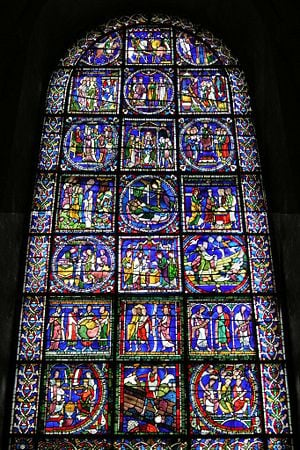

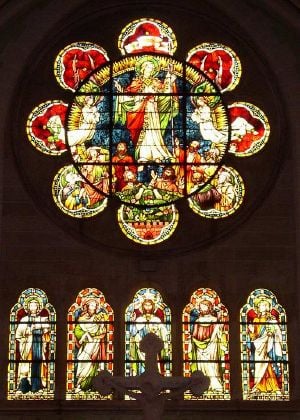

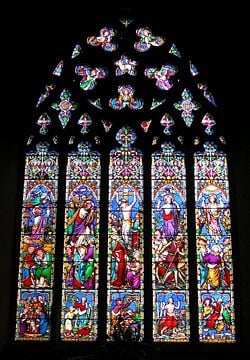

Stained glass windows are created by cutting pieces of colored glass to match a drawn template and setting them into place in a mesh of lead cames and supporting the whole with rigid metal bars. Details such as facial features can be painted on the surface of the glass, and stains of bright yellow applied to enliven white areas. The effect is to add an appearance of brilliance and richness to a church interior, while the media lends itself to narratives. If the lead is properly maintained, stained glass is extremely durable and many windows have been in place for centuries.

In Italy, during the Byzantine period, windows were often filled with thin slices of alabaster, which although not figurative, gave a brightly patterned effect when sunlight was transmitted through them. There is a rare example of alabaster being used for a figurative subject in the Dove of the Holy Spirit, in the chancel of St Peter's in Rome.[6]

The earliest known figurative stained glass panel is a small head of Christ (with many fragments missing) found near the royal abbey of Lorsch-an-der-Bergstrasse and thought to date from the ninth century. Although a few panels dating from the tenth and eleventh centuries exist in museums, the earliest known are four panels of King David and three prophets at Augsburg Cathedral in Germany dating from about 1100. Stained Glass windows were a major art form in the cathedrals and churches of France, Spain, England and Germany. Although not as numerous, there are also some fine windows in Italy, notably the rose window by duccio in Siena Cathedral and those at the base of the dome in Florence Cathedral, which were designed by the most famous Florentine artists of the early fifteenth century including Donatello, Uccello, and Ghiberti.

In many of the decorative schemes that illustrate the life of Jesus, the narrative is set into the context of related stories drawn from the Old Testament and sometimes from the Acts of the Apostles.

Certain characters of the Old Testament, through particular incidents in their lives, are seen to prefigure Jesus in different ways. Often their actions or temperament is set in contrast to that of Jesus. For example, according to the Bible, Adam, created in purity and innocence by God, fell to temptation and led humankind into sin. Jesus, on the other hand, lived a blameless life and died for the redemption of the sin of Adam and all his descendants.

The way in which the cross-referencing is achieved is usually by a simple juxtaposition, particularly in mediaeval stained glass windows, where the narrative of Jesus occupies the central panels of a window and on either side are the related incidents from the Old Testament or Acts. In this, the windows have much in common with the Biblia Pauperum which were often arranged in this manner, and were sometimes used as a source of design. In nineteenth and early twentieth century windows, the sections holding the major narrative are often larger and the Old Testament panels might be quite small. A similar arrangement is sometimes used in Early Renaissance panel painting.

Panel painting

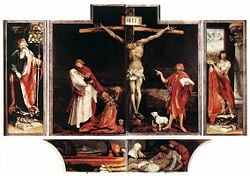

Panel Paintings are those done on specially prepared wooden surfaces. Before the technique of oil painting was introduced by the Dutch masters of the fifteenth century, panel paintings was done using tempera in which powdered color was mixed with egg yolk. It was applied on a white ground, the colors being built up in layers, with tiny brushstrokes, the details often finished with gold leaf. With the invention of oil painting and its introduction to Italy and other countries of Europe, it became easier to create large works of art.

In the first century, a similar technique was employed in Egypt to paint funerary portraits. Many of these remain in excellent condition. Tempera panels were a common art form in the Byzantine world and are the preferred method for creating icons. Because the method was very meticulous, tempera paintings are often small, and were frequently grouped into a single unit with hinged sections, known as a diptych, triptych or polyptych, depending on its number of parts. Some large altarpiece paintings exist, particularly in Italy where, in the 13th century, Duccio, Cimabue and Giotto created the three magnificent Madonnas that now hang in the Uffizi Gallery, but once graced three of the churches of Florence. With the development of oil painting, oil on panel began to replace tempera as a favoured method of enhancing a church. The oil paint lent itself to a richer and deeper quality of colour than tempera, and permitted the painting of textures in ways that were highly realistic.

Oil on canvas

Oil paint comprises ground pigment mixed with linseed and perhaps other oils. It is a medium which takes a long time to dry, and lends itself to varied methods and styles of application. It can be used on a rigid wooden panel, but because it remains flexible, it can also be applied to a base of canvas made from densely-woven linen flax, hence, the linseed oil and the canvas base are both products of the same plant which is harvested in Northern Europe. With canvas spread over a wooden frame as a base, paintings can be made very large and still light in weight, and relatively transportable though liable to damage. In the latter fifteenth century, oil paintings were generally done in a meticulous manner that simulated the smoothness and luminescent layering of tempera. In the sixteenth century the handling of the paint became freer and painters exploited the possibility of laying paint on in broad, visible and varied brushstrokes.

Oil paintings initially became a popular method for producing altarpieces and soon replaced tempera for this purpose. The ease with which large paintings could be created meant that not only did very large altar paintings proliferate, taking the place of polyptychs made of small panels, but because they were of relatively light weight, such pictures could be used on ceilings, by setting them into wooden frames and without the trouble of the artist having to work laboriously on a scaffold. Famous Venetian painters, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese produced many such pictures. Pieter Paul Rubens painted a "Passion of Christ" in a number of large and magnificent canvases.

Wood

Because the nature of wood lends itself to easy working it has been a favoured material for decorative fittings within churches. It can be carved, veneered and inlaid with other materials. It can be lacquered, painted or gilt. It can be used for artefacts and free-standing sculptures. It is relatively robust unless finely carved, but must be protected from mould and insects.

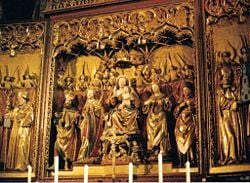

In the Byzantine period ivory rather than wood was the preferred material for carving into small religious objects, caskets, panels and furniture, the throne of Maximianus of Ravenna, with carved reliefs of Biblical stories and saints, being the finest example. The oldest large wooden sculpture to have survived in Europe is the painted and gilt oak Crucifix of Archbishop Gero, 969-971, in Cologne Cathedral.[7] Subsequent to this time, there are an increasing number of surviving large Crucifixes and free-standing statues, large and small, often of the Virgin and Child. Much of the wooden furniture in churches is richly decorated with carved figures, as are structural parts such as roof bosses and beams. Carved and decorated wooden screens and reredos remain from the thirteenth century onwards. In Germany, in particular, the skill of making carved altarpieces reached a high level in the Late Gothic/Early Renaissance. In Belgium, wood carving reached a height in the Baroque period, when the great pulpits were carved.

Metal

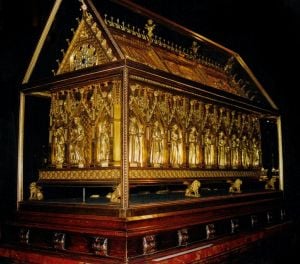

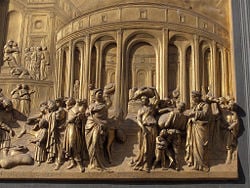

Christian metalwork can take a vast number of forms, from a tiny Crucifix to a large statue or elaborate tomb or screen. The metals used can range from the finest gold leaf or silver filigree to cast bronze and wrought iron. Metal was commonly used for Communion vessels, for candelabra and all types of small fittings, and lent itself to being richly decorated by a number of techniques. It can be moulded, hammered, twisted, engraved, inlaid and gilded. If properly maintained, metal is extremely durable.

From the early Byzantine period there remains a number of Communion vessels, some of which, like the paten found at Antioch, have repousse decoration of religious subjects. The 8th century Byzantine crucifixes and the famous Ardagh Chalice from Ireland, are decorated with cloisonne. From the Romanesque period onwards are the golden Altar frontal of Basel Cathedral, 1022, Bonanno Pisano's bronze doors at Monreale Cathedral, 1185, the magnificent font of St Michael's, Hildesheim, 1240 and reliquaries, altar frontals and other such objects. In the early 1400s, the renowned sculptor, Donatello was commissioned to create series of figures for the chancel screen of the Basilica di Sant' Antonio in Padua.

Mixed media

It is normal for many objects to combine several media. Oil paintings, for example, usually come in ornate frames of gilt wood. Among the most decorative objects that are to be found within churches are those constructed of mixed media, in which any of the above may be combined.

In the Basilica di San Marco, Venice is the famous Pala d'Oro, a glorious altarpiece pieced together over several hundred years so that it has elements of the Gothic as well as the Byzantine. The Pala d'Oro is made of gold and is set with enamels, jewels, semi-precious stones and pearls. In the Baroque period the use of mixed media reached a high point as great altarpieces were constructed out of marble, wood and metal, often containing oil paintings as well. Some of these altarpieces create illusionistic effects, as if the viewer were having a vision. Other objects that are commonly of mixed media are devotional statues, particularly of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which most commonly have faces of painted plaster, but also of wax, ivory, porcelain and terracotta. They are often dressed in elaborate satin garments decorated with metallic braid and lace, pearls, beads and occasionally jewels and may be decked with jewellery and trinkets offered by the faithful. Another important mixed-media art form is the tableau, which may comprise a Gethsemane or a Christmas Creche. These may be elaborate and exquisite, or may be assembled by the Sunday School using cotton-reels bodies, ping-pong ball heads and bottle-top crowns.

Themes

Bible Stories

The most common theme for the Poor Man's Bible is the Life of Christ, the story of the Birth, Life, Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus. This may be related in a continuous sequence of pictures, either in paint, mosaic, wood sculpture or stained glass, and located either around the walls of a church or, particularly in French Cathedrals, in niches in a screen that surrounds the Sanctuary, so that they might be seen by people walking around the ambulatory.

An important form of visual narration is the so-called Stations of the Cross cycle, telling of the Passion (trial and execution) of Jesus. These appear in almost all Roman Catholic churches and are used for devotional purposes as the prompts for a series of meditations and prayers. The Stations of the Cross usually take the form of oil paintings, molded and painted plaster, or carved wood set into frames and suspended on the aisle walls so that the sequence may be easily followed.

The aspect of the Old Testament that appears most frequently in a continuous narrative form is the Creation and the Downfall of humankind through the actions of Adam and Eve.

Many churches and cathedrals are dedicated to a particular biblical or early Christian saint and bear the name of that saint. Other churches have been founded by or have been associated with some person who was later canonised. These associations are often celebrated in the decoration of the church, to encourage worshippers to emulate the piety, good works, or steadfast faith of the saint. Sometimes saints are shown together in a sort of pictorial gallery, but the depiction of narratives is also common. This may take the form of a single incident, such as Saint Sebastian tied to a tree and bristling with arrows or St Christopher carrying the Christ Child across the river, or the saint's life may be shown in a narrative sequence, similar to the way in which the life of Jesus is depicted.

The depiction of prophets, apostles, saints, patriarchs and other people associated with the church often have a place in the decorative scheme. The thematic use of such figures may be a very obvious one. There may, for example, be a row of stained glass windows showing the prophets that predicted the coming of the Messiah. Or within a carved stone screen might stand statues of those monarchs who were particularly devoted to the church. The apostles, usually twelve in number but sometimes accompanied by St Paul, John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene and others, are a frequent subject. The upright, standing figures particularly lent themselves to architectural decoration and the often appear in a columnar form around doorways or in tiers on the façades of cathedrals.

Theology

One of the major purposes of an artistic scheme, or Poor Man's Bible, within a church was to show the viewer the "Way to Salvation." The Revelation that the Poor Man's Bible seeks to share with the viewer is the revelation of God's plan for humanity's Salvation through sending his son, Jesus, to be born as a human baby, to live among people and to die a cruel death to absolve the sins committed by humanity. Jesus, as depicted on the walls, domes and windows of churches, is the Revelation of God's love, his grace, his mercy and his glory. This, broadly speaking, is the theme of every Poor Man's Bible. The Revelation of God's grace through Jesus might be shown in several ways. The focus might be on his birth, on his sacrificial death, on his subsequent resurrection from the dead, or upon his coming in glory.

The Apostolic Succession

Part of the role of the decorated church was to convey that the Church was the body of Christian believers. The decorative schemes in churches have often reflected that the Church was founded by the apostles and its history goes back to Jesus' time. One way a church might reflect this was to have the relics of an apostle or an early martyr. There was a great trade in body parts of different religious notables.

With the relics came beautiful reliquaries of ivory, gold and precious stones. Some saints' remains were claimed to have healing powers. This phenomenon produced pilgrimage, which was very lucrative for the church involved and, if the saint was of sufficient renown, for all the churches and monasteries that sprang up along the pilgrimage route. Three of the most popular pilgrimage churches in the Middle Ages were The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostella in Spain and Canterbury Cathedral in Kent. Churches, particularly monasteries, honored their own. Thomas of Canterbury is an example. This archbishop was murdered by King Henry II's henchmen while praying at a side altar in the cathedral. The King himself made a penitent pilgrimage to the cathedral. Even though much of the stained glass has been lost over the years, there still remains two windows which show some of the many healings and miracles associated with St Thomas, both before and after his death.

In churches that are monastic, there is often an emphasis on the saints that belonged to that particular order. It is not uncommon to see religious paintings of the Blessed Virgin enthroned with the Christ Child and surrounded by numerous saints, including some of the first century, and some belonging to the particular Order who commissioned the work.

Another way for the church to confirm its role was through the administration of the rites. Some churches have decorative schemes which support this role of the church, illustrating the various rites and sacraments. The Church of St John at Tideswell in Derbyshire has a particularly fine set of 20th century bench-ends by Advent and William Hunstone, showing the rites of Baptism, Confirmation, and Ordination.

God's gifts

God, who according to Genesis, made the Heaven and the Earth, also created man in his own likeness[8] and gave to humankind also the gift of creativity. It is a lesser theme that consistently runs through religious art. There are, in particular, and understandably, many depictions of stone masons, wood carvers, painters and glaziers at work. There are also countless depictions of monks, musicians and scribes.

Outstanding examples

The Baptistery at Padua The decoration of this small cubic domed church which stands next to the Cathedral of Padua is the masterpiece of Giusto di Menabuoi and comprises one of the most complete and comprehensive frescoed Poor Man's Bibles.[9]

The Collegiate Church of San Gimignano The church of Collegiata di San Gimignano contains a remarkably intact and consistent scheme by a number of different painters, comprising a Last Judgement, an Old Testament narrative including the story of Job and the Life of Christ, as well as several other significant frescoes and artworks.

The mosaic of St Mark's, Venice The glorious mosaic scheme of St Mark's Basilica covers the portals, porches, walls, vaults, domes and floors. There is also a magnificent Rood Screen and the spectacular Pala d'Oro as well as reliquaries of every imaginable description.[10]

The sculpture and windows of Chartres Cathedral Chartres Cathedral contains an incomparable range of stained glass including some of the earliest in situ in the world. It also has three richly carved Gothic portals of which the stylized twelfth century figures of the western Royal Portal are the most renowned and are reproduced in countless art historical texts.[11]

The windows of Canterbury Cathedral Canterbury Cathedral contains a greater number of early Gothic windows than any other English Cathedral. Unfortunately, the nineteenth century saw the removal of some of the glass to museums and private collections, with reproductions put in their place. That said, even the fragmentary Poor Man's Bible window is worthy of a "pilgrimage."

The altarpiece of the Mystic Lamb, Ghent The Cathedral of Ghent contains this sublime masterpiece of the altarpiece-painters' art. It is a Poor Man's Bible within itself, the various scenes representing the Fall of Man and the Salvation, with the Mystic Lamb of God and the enthroned Christ at its centre. The fame that it brought to the brothers van Eyck was so great that there is a huge statuary group to their honour outside the cathedral.[12]

The paintings in San Zaccaria, Venice St Zachariah was the father of John the Baptist. His story is told in the Gospel of Luke. The church of San Zaccaria di Venezia contains a remarkable number of huge oil paintings by many of Venice's greatest painters and includes Bellini's most famous altarpiece of the Madonna and Child surrounded by Saints.[13]

The windows of St. Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney The windows of St Andrew's are not online. The Victorian era saw the revival of many ancient crafts as numerous churches were restored; new churches were built in developing industrial towns and in the colonies. In Australia about twelve of the existent cathedrals were constructed within a period of fifty years. The earliest of them is St Andrew's Anglican Cathedral in Sydney which has one of the earliest complete schemes of English nineteenth century glass. It shows the Life of Jesus, the Miracles and the Parables. The set was completed and installed by Hardman of Birmingham for the consecration in 1868. A short walk away is St Mary's Catholic Cathedral with another cycle of Hardman windows dating from the 1880s to the 1930s.

Notes

- ↑ Orthodox Photos, Moldovita Convent, Romania. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Classic Mosiacs, Interior Dome. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Classic Mosiacs, Prassede. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Sacred Destinations, Cathedral Pictures. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Wells Cathedral, West Front. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ St. Peters Basilica, Cathedra Petri. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Instructional 1, Crucifix of Archbishop Gero. c. 970. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Book of Genesis Ch. 1:26.

- ↑ EasyWeb, Life of Giusto di Menabuoi. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Classical Mosiacs, Ancient Mosaics. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Saint John's State University, Chartres Cathedral Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Web Museum, Paris, Eyck, Jan Van. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Paradox Palace, San Zaccaria.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Sarah. Stained Glass, an Illustrated History. Bracken Books, 1990. ISBN 1858911575.

- Carli, Enzo. Sienese Painting. Summerfield Press, 1983. ISBN 0584500025.

- Chastel, Andre. The Art of the Italian Renaissance. Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1988. ISBN 0881681393.

- Eimerl, Sarel. The World of Giotto. Amsterdam: Time-Life Books, 1967. ISBN 0900658150.

- Jenkins, Simon. England's Thousand Best Churches. Allen Lane, Penguin Press, 1999. ISBN 0713992816.

- Martindale, Andrew. The Rise of the Artist in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. Thames and Hudson, 1972. ISBN 0500560064.

- Swan, Wim. The Gothic Cathedral. Omega Books, 1988. ISBN 090785348X.

- Swan, Wim. Art and Architecture of the Late Middle Ages. Omega Books, 1988. ISBN 0907853358.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.