Japan's Korea War: First Invasion (1592-1596)

| Japan's Korea War: First Invasion The Imjin War (1592–1598) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

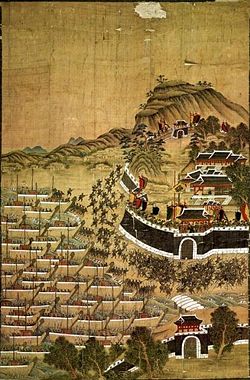

Japanese landing at Busan, 1592 The Seige of Busan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Korea under the Joseon Dynasty, China under the Ming Dynasty, Jianzhou Jurchens |

Japan under Toyotomi Hideyoshi | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Korea: King Seonjo Prince Gwanghae Yi Sun-sin†, Gwon Yul, Yu Seong-ryong, Yi Eok-gi†, Won Gyun†, Kim Myeong-won, Yi Il, Shin Rip†, Gwak Jae-woo, Kim Shi-Min† China: Li Rusong† (pr.), Li Rubai, Ma Gui (pr.), Qian Shi-zhen, Ren Ziqiang, Yang Yuan, Zhang Shijue, Chen Lin |

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Katō Kiyomasa, Konishi Yukinaga, Kuroda Nagamasa, Todo Takatora, Katō Yoshiaki, Mōri Terumoto, Ukita Hideie, Kuki Yoshitaka, So Yoshitoshi, Kobayakawa Takakage, Wakizaka Yasuharu, Kurushima Michifusa† | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Korea: 40,000 Korean Army, (at the beginning) at least 22,600 Korean volunteers and insurgents China: 1st.(1592–1593) over 150,000 2nd.(1597–1598) over 100,000 |

1st.(1592–1593) About 160,000 2nd.(1597–1598) About 140,000 | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| Korea: Unknown China: over 30,000 |

total 100,000 (est.) | ||||||

Japan made two invasions of Korea, in 1592 and 1596, starting a war that lasted until, including a truce period, 1598. They are also known as Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea, and the Seven Year War in reference to its span.[1] involved China and resulted in further conflicts on the Korean Peninsula. The Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) refers to two invasions of Korea by Japan in those years, and to the resulting conflicts on the Korean Peninsula. Kampaku Toyotomi Hideyoshi led the newly unified Japan into these invasions with the professed goal of conquering Ming Dynasty China.

The first invasion (1592–1593) is literally called the "Japanese (= 倭 |wae|) War (= 亂 |lan|) of Imjin" (1592 being an imjin (= water—dragon) year in the sexagenary cycle) in Korean and Bunroku no eki in Japanese (Bunroku referring to the Japanese era under the Emperor Go-Yōzei, spanning the period from 1592 to 1596).

In addition to the human losses, Korea suffered tremendous cultural, economic, and infrastructural damage, including a large reduction in the amount of arable land,[1] destruction and confiscation of significant artworks, artifacts, and historical documents, and abductions of artisans and technicians.[2] The heavy financial burden placed on China by the war adversely affected its military capabilities and contributed to the fall of the Han Ming Dynasty and the rise of the Manchurian Qing Dynasty.[3]

| Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598) |

|---|

| Busan – Tadaejin – Tongnae – Sangju – Ch'ungju – Okpo – 1st Sacheon – Imjin River – Dangpo – Danghangpo – Hansando – Pyongyang – Chonju – Haejongchang – Busan – Jinju – Pyeongyang – Byokchekwan – Haengju – Jinju – Busan – Hwawangsan – Chilchonryang – Namwon – Myeongnyang – Ulsan – 2nd Sacheon – Noryang Point |

| Korean Name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul: | 임진왜란 / 정유재란 |

| Hanja: | 壬辰倭亂 / 丁酉再亂 |

| Revised Romanization: | Imjin waeran / Jeong(-)yu jaeran |

| McCune-Reischauer: | Imjin waeran / Chŏng'yu chaeran |

| Japanese Name | |

| Japanese: | 文禄の役 / 慶長の役 |

| Hepburn Romaji: | Bunroku no Eki/ Keichō no Eki |

| Chinese Name | |

| Traditional Chinese: | 壬辰衛國戰爭(萬曆朝鮮之役) |

| Simplified Chinese: | 壬辰卫国战争(万历朝鲜之役) |

| Hanyu Pinyin: | Rénchén Wèiguó Zhànzhēng (Wànlì Cháoxiǎn Zhīyì) |

|

Jeulmun Period

|

Background

By the last decade of the sixteenth century, Toyotomi Hideyoshi as a daimyo under Emperor Ōgimachi had unified all of Japan in a brief period of peace. Motivated in part by a need to satisfy the perpetual hunger for territory of his vassals and to find employment for restive samurai, he began to plan the conquest of Ming Dynasty China. He initially revealed his plan to Mōri Terumoto in 1586, and pursued it after having defeated the clans of Shimazu and Hōjō. Thousands of troops were mobilized and trained; weapons and supplies were gathered; and hundreds of arquebuses were imported from Portugal. Hideyoshi tried but failed to hire two Portuguese galleons to join the invasion; therefore, hundreds of ships were quickly built to carry the entire Japanese army across the sea.

Hideyoshi sent ambassadors to request the Joseon court to allow his troops to move through the Korean peninsula to China. His first request was ignored, and the second request was snubbed after King Seonjo had sent envoys to Hideyoshi's government, although it is claimed that their observations indicated that Hideyoshi posed no threat. After the denial of his second request, Hideyoshi launched his armies against Korea in 1592. Tokugawa Ieyasu, Konishi Yukinaga, and Sō Yoshitoshi were among those who opposed Hideyoshi's plan and tried to arbitrate between Hideyoshi and the Joseon court.

The Korean army in the south consisted of only a few garrison troops spread all over the provinces, and there was no autonomous military force that could be deployed. Many of the troops were sent to the northern frontier to defend Korean settlements from Jurchen raiders. Unlike the situation over a thousand years earlier where Chinese dynasties had an antagonistic relationship with the largest of the Korean polities (see List of Chinese invasions of Goguryeo), the Neo-Confucianist Joseon Dynasty had a close trading relationship with Ming China, and also enjoyed a continuous trade relationship with Japan.[4]

Thus, by the 1580s, the Korean military had fallen into decline. Also, the decision to ignore weapons technology weakened the Korean army considerably. The conflict against the Jurchens in 1582 showed that Korea lacked a strong military in terms of both size and capabilities. Admiral Yi I (1536–1584), then an influential scholar and philosopher, advised the king to maintain an army with a minimum size of 100,000 to no avail, and only a few scholars foresaw a Japanese invasion.

In the 1580s, Yu Seong-ryong (유성룡; 柳成龍), a prominent scholar, feared an invasion by Japan and thus wanted to strengthen the military. He believed that all men, regardless of their social status (including slaves), should be conscripted. Yu also wanted to reorganize the military, develop more advanced arquebuses, and improve armor even for the common foot soldier. Yu also argued for stronger castles. However, his proposals were dismissed and the Korean court remained blissfully ignorant. Yu later became Prime Minister of Korea, and one of Admiral Yi's strongest advocates.

Since they were in terrible shape and he doubted their efficacy in defense, Yu insisted on rebuilding Korean castles near the coasts and garrisoning them with active soldiers. Yu wanted repaired walls with cannon holes and long, easily defensible walls with towers, similar to castles in Europe. However, these proposals were opposed by most advisers of the court, who believed that Japan was not in a position to attack Korea, and Yu's proposals were snubbed. They also rejected the proposals to repair castles because of the amounts of money and labor that would have been required.

Weapons and equipment

Muskets (arquebuses) and bows

One reason the Japanese so dominated the early stages of the war was their development and implementation of advanced muskets, first introduced 50 years earlier by Portuguese traders in 1543, in Tanegashima, a small island south of Kyūshū.[5] The arquebuses, first used in the Siege of Busan, daunted the Korean forces who had no effective way of countering these new weapons. The acquisition of the weapons, lightweight versions of matchlock muskets, was the first occasion of an opening of the Japanese market to the West's science and technology. The local lord, Tanegashima Tokiaki, impressed by the demonstration, purchased two of these firearms, from which he soon began to manufacture copies. About 20 years later, the arquebuses were standardized and improved from the Portuguese originals, and mass-produced throughout Japan at the rate of at least several thousand per year and were used with great success.[6]

Korea, however, disassociated from Western weapons, and while sporadic usage of short-barrelled personal Chinese-style firearms Seungja, Baekje, etc., was seen, the main emphasis was on archery, fire arrows, and cannons. Korea's first reaction to the arquebus was much different than the Japanese. When the first arquebus was introduced to Korea in 1590, during a visit of an embassy sent by King Seonjo to Hideyoshi, the weapon was given a cursory examination and was promptly archived in the Korean royal arsenal and forgotten about.

Yu Seong-ryong, who wrote the Jingbirok (Record of Reprimands and Admonition), advocated the use of the new acquisition and its mass production as part of the strengthening of the national defenses, but his recommendations in favor of the creation of arquebus squads were dismissed as "something laughable,"[7] and Korean bows continued to be the standard long-range arms. The maximum range of the Korean bow was 460 m, in contrast to its Japanese counterpart, a heavy composite bow whose range was 380 m[8] and which sacrificed raw distance for improved accuracy. In battle, Korean archers would find themselves outranged against Japanese musketeers, who had a maximum range of about 500 m. Still, the bow had significant utility with a short reload time (six arrows could be shot while an arquebus/musket was being loaded and fired) and was a strong asset. However, training men to become skilled archers was an arduous and repetitive task, which could take several years. The arquebus' lack of accuracy was compensated by effective technique; heavy volley fire and striking firepower that could easily pierce iron armor at closer distances. The overall efficiency of the weapon had been proven at the Battle of Nagashino before being used in the Korean campaigns.

Armor

Korean soldiers had a notable lack of armor. Although Korean troops were equipped with brigandine and chain mail armor during the Goryeo Dynasty (918 – 1392), its usage declined by the mid-sixteenth century. Commanders saw no need for armor because of their confidence in their projectile weapons, which they believed made face-to-face combat less likely. Although the government mandated wearing armor for all ranks, generally only officers complied. Most soldiers hesitated to wear armor due to its bulky nature and the expense required to obtain fitted armor (at the time, most members of the military, save for the higher officer ranks, were from the poorer civilian classes).

A common Korean soldier wore a heavy, colored vest (usually black) over their normal white clothes. A strictly ceremonial felt hat gave some limited protection as well. This uniform allowed easy movement and speed but no protection against bullets, arrows, or swords. Korean soldiers often used a short spear called dangpa-chang as their main weapon.

Japanese foot soldiers wore iron or leather plate and/or chainmail over their chest, arms, and legs. Shin guards added protection to the lower legs and feet. A round conical hat was worn by the Japanese, usually painted with an insignia of a samurai's crest. Shoes were not usually worn among the foot soldiers. Chinese Ming dynasty soldiers wore steel helmets and brigandine armor which covered their chest, arms, and hung over their legs.

Probably the only military division Korea excelled in was the navy. Largely through Admiral Yi's preparations, the navy was capable of successfully defeating the Japanese navy. The Korean navy was mainly made up of standard panokseons, and Admiral Yi's newly designed turtle ships, loosely based on an earlier ship of the same name and similar design. Each panokseon had 32 large Korean cannons and multiple hwachas, (rocket launchers) often preferring to fight at a distance, utilizing their firepower and range (for example, see Battle of Noryang Point). Japanese commanders preferred to engage in close combat, as the Japanese fleet excelled in boarding and the ensuing mêlée combat. The advantage of long range weapons Korea had, however, severely limited a boarding attack strategy (boarding attacks and subsequent struggles still occurred infrequently, with mixed results) and ultimately resulted in Japanese defeats at sea.

Although the Korean military in general lacked firearms, Korean sailors had a wide selection of cannons, grenades, and mortars at their disposal. Korean versions of cannons were first developed in the 1400 s under King Sejong (1418–1450) for use mainly on battleships and castles and were improved vastly over the years. However, cannons in Korea were not modified down to the personal level, due to infighting and philosophical barriers (the Neo-Confucianism ethic in Korea during the Joseon era was very conservative), and as such, personal firearms were rejected by the Korean military at large. The Korean cannons that were used were much more powerful than their Japanese counterparts. Large wooden arrows with iron tips and fins, called daejon, were used to pierce hulls of enemy ships.

Initial invasion (1592–1593)

| Japanese first invasion wave[9] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st div. | Konishi Yukinaga | 7,000 | |

| Sō Yoshitoshi | 5,000 | ||

| Matsuura Shigenobu | 3,000 | ||

| Arima Harunobu | 2,000 | ||

| Ōmura Yoshiaki (ja) | 2,000 | ||

| Gotō Sumiharu | 700 | 18,700 | |

| 2nd div. | Katō Kiyomasa | 10,000 | |

| Nabeshima Naoshige | 12,000 | ||

| Sagara Yorifusa (ja) | 800 | 22,800 | |

| 3rd div. | Kuroda Nagamasa | 5,000 | |

| Ōtomo Yoshimasa | 6,000 | 11,000 | |

| 4th div. | Shimazu Yoshihiro | 10,000 | |

| Mōri Yoshimasa (ja) | 2,000 | ||

| Takahashi Mototane (ja), Akizuki Tanenaga, Itō Suketaka (ja), Shimazu Tadatoyo[10] | 2,000 | 14,000 | |

| 5th div. | Fukushima Masanori | 4,800 | |

| Toda Katsutaka | 3,900 | ||

| Chōsokabe Motochika | 3,000 | ||

| Ikoma Chikamasa | 5,500 | ||

| Ikushima (Kurushima Michifusa)? | 700 | ||

| Hachisuka Iemasa (ja) | 7,200 | 25,000 (sic) | |

| 6th div. | Kobayakawa Takakage | 10,000 | |

| Kobayakawa Hidekane, Tachibana Muneshige, Tachibana Naotsugu (ja), Tsukushi Hirokado, Ankokuji Ekei | 5,700 | 15,700 | |

| 7th div. | Mōri Terumoto | 30,000 | 30,000 |

| Subtotal | 137,200 | ||

| Reservers (8th div.) | Ukita Hideie (Tsushima Island) | 10,000 | |

| (9th div.) | Toyotomi Hidekatsu (ja) and Hosokawa Tadaoki (ja) (Iki Island) | 11,500 | 22,500 |

| Subtotal | 158,700 | ||

| Naval force | Kuki Yoshitaka, Wakisaka Yasuharu, Katō Yoshiaki, Otani Yoshitsugu | 9,000 | |

| Subtotal | 167,700 | ||

| Stationed force at Nagoya | Ieyasu, Uesugi, Gamō, and others | 75,000 | |

| Total | 234,700 | ||

First landing. The invasion began when Japanese forces of the First and Second Divisions, under Katō Kiyomasa and Konishi Yukinaga, respectively, landed simultaneously at Busan and Dadaejin (다대진), respectively, on May 23, 1592, with a combined force of 150,000 soldiers.[11] The Siege of Busan was won after the Korean troops' morale crumbled: their general, Jeong Bal, died of a gunshot wound. Dadaejin fell within some hours. The cities were fortified to allow safe passage for Japanese reinforcements, supplies, and ships.

Siege of Dongnae. After capturing the southernmost port city Busan, Konishi's troops moved northwest to where the Dongnae fortress was, and overran the Korean troops there, which were led by Song Sang-hyn. Apparently, all troops there were slaughtered along with their commander.

Battle of Sangju. After securing the ports, the First Division (under Konishi Yukinaga) with 25,000 men marched quickly north to Sangju. Sangju was defended by Yi Il, a senior general who had fought the Jurchens in northern Korea. However, with a small garrison and a weak castle, Yi Il's men fell again to the powerful arquebuses.

Konishi then crossed Choryang Pass, which was a major strategic point that the Koreans failed to guard when Sin Rip made the decision to pull his cavalry back the Chungju, believing that the cavalry would fight easily in open ground. This enabled the Japanese army to simply pass the point without any resistance at all. The failure to defend Choryang Pass led to the capture of Hanseong (present-day Seoul).

Battle of Chungju. Konishi soon reached Chungju, which was defended by a cavalry division under the command of Sin Rip. The newly-recruited cavalry division of 8,000, having been outnumbered and limited to melee weapons, was overwhelmed by 19,000 Japanese soldiers equipped with arquebuses. This marked the last defense line to Hanyang, and the Japanese forces journeyed north without much complication.

Upon hearing of General Sin Rip's defeat, the Yi court took flight toward Pyongyang. In Kaesong, the Korean commoners mourned bitterly because they believed that their king was abandoning them. The Yi court would eventually travel as far as the very northern states of Korea, and the prince would be sent with other ambassadors to ask the Ming Emperor for military aid.

Meanwhile, the Second Division of 23,000 men under Katō Kiyomasa captured Gyeongju, the former capital of Korea during the Silla Dynasty, and massive looting and burning took place. A series of minor battles between the Koreans and Japanese led Katō to Chuksan, and eventually Seoul in a month.

Capture of Hanseong. Chungju was the last line of defense for the Koreans and the road to Hanseong (present-day Seoul) was open to the Japanese. Both Generals Katō and Konishi vied to earn the honor of reaching Hanseong first, and the Third Division under Kuroda Nagamasa was not far behind. In the end, Konishi managed to arrive near Hanseong first, and planned to attack the East Gate.

To their surprise, the city was left undefended and was found burned and destroyed. Konishi and his men simply walked through the massive gates. King Seonjo had already fled to Pyongyang the day before. There were no soldiers either. Korean commoners had looted and destroyed the food warehouses and armories believing their King had abandoned them and the Japanese failed to collect any treasures or supplies, which was a contrast to the Japanese looting that had taken place in the southern provinces.

Japanese northern campaign

Japanese troops ravaged and looted many key towns in the southern part of Korea, took Pyongyang and advanced as far north as the Yalu and Tumen rivers. By 1593, Konishi was already planning to invade China. Of the Second Division, however, Katō Kiyomasa was still unhappy because of Konishi's glory from the capture of Seoul. Katō planned to invade Hamgyong province in northern Korea and begin his China campaign. With an army of 20,000 men, Katō advanced north, capturing every single castle he arrived at. This included all the castles along Korea's eastern border.

After defeating the Korean armies, he turned north to China and attacked a Jurchen fortress, capturing it. However, after a counterattack by the Jurchen forced Kato to return south. Kato's campaign in China was the only time the Japanese ever reached their goal.

While the Korean forces on land were suffering from the Japanese attacks, Admiral Yi Sun-sin, who kept a war diary, was preparing for battle against the Japanese ships docked in Busan at his base in Yeosu. In June 1592, a small Korean fleet, commanded by Yi destroyed Japanese flotillas and wrought havoc on Japanese logistics in The Battle of Okpo was a two-day fight around the harbor of Okpo at Geoje Island in 1592. It was the first naval battle of the Imjin War and the first victory of Admiral Yi.

During the Battle of Sacheon (1592), the Korean iron-roofed Geobukseon, or turtle ships, were introduced. After another Korean victory at the Battle of Dangpo, Battle of Danghangpo, Japanese generals at Busan began to panic, fearing that their supply lines would be destroyed, so therefore the Japanese naval generals decided to kill Admiral Yi before his threat to Japanese supply ships escalated and sent Wakizaka Yasuharu to destroy him. However, at the Battle of Hansando, Wakizaka was defeated. Admiral Yi's victory at Hansan Island effectively ended Hideyoshi's dreams of conquering Ming China, which was his original goal in invading Korea. The supply routes through the Yellow Sea had to remain open in order for his troops to have enough supplies and reinforcements to invade China.

Thus, Konishi Yukinaga, the commander of the contingent of troops in Pyongyang could not move further north due to lack of supplies, nor could more troops be sent to him because there was not enough food to feed them. It took five times the resources in food and men to move supplies via the land route over Korea's primitive roads. Furthermore, moving supplies overland left them vulnerable to attacks by regular Chinese and Korean forces as well as Korean irregular or guerrilla forces (the Righteous Armies 의병/義兵) that were becoming increasingly active as the war progressed. In November 1592, Yi attacked the Japanese naval headquarters at Busan. Yi managed to leave with all of his ships intact, while inflicting damage on several hundred enemy ships still in their docks. Focusing on naval control, a 1592 battle near Hansan Island succeeded in severely disrupting the Japanese naval supply lines.[12]

The Japanese lost control of the Korea Strait after such naval defeats, and their activities were largely limited around Busan until the Battle of Chilcheollyang in 1597. Without the continuous supplies coming from Busan, the Japanese army lost their initial advantage and could not proceed any further beyond Pyongyang. Much credit for the war's eventual outcome has been attributed to Admiral Yi's efforts.

Siege of Jinju

Jinju (진주) was a large castle that defended Jeolla Province. The Japanese commanders knew that control of Jinju would mean the fall of Jeolla. Therefore, a large army under Hosokawa Tadaoki gleefully approached Jinju. Jinju was defended by Kim Shi-Min (김시민), one of the better generals in Korea, commanding a Korean garrison of 3,000 men. Kim had recently acquired about 200 new arquebuses that were equal in strength to the Japanese guns. With the help of arquebuses, cannon, and mortars, Kim and the Koreans were able to drive back the Japanese from Jeolla Province. Hosokawa lost over 30,000 men. The battle at Jinju is considered one of the greatest victories of Korea because it prevented the Japanese from entering Jeolla. In 1593, Jinju would fall to the Japanese.[13]

Korean militia corps

Throughout the history of Korea, irregular armies have risen to fight against invaders. It was no different during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598). As the Joseon military began to break down, Korean irregular volunteers organized themselves and began to operate against the Japanese forces. Both Korean civilians and Buddhist monks gathered to form a militia. The militias' main jobs were to harass Japanese communication lines, ambush armies, assassinate Japanese commanders, and provide reinforcements.

Insurgency resistance was especially strong in the southern provinces of Chungcheong, Jeolla, and Gyeongsang. Gwak Jae-woo (곽재우), Jo Heon (조헌), Kim Cheon-il (김천일), Go Gyeong-myeong (고경명), and Jeong In-hong (정인홍) were among the notable insurgency leaders. Korean militias also were strong in northern Korea during Kato Kiyomasa's northern campaign.

Gwak Jae-woo is one of the most celebrated heroes of the war. He was originally a landowner in Gyeongsang province, but the urgency of the war caused him to begin gathering volunteers to fight the Japanese. In popular depiction, Gwak Jae-woo is wearing an all-red tunic, claiming that the tunic was stained with the blood of Korean innocents slaughtered by the Japanese. Today, Gwak is remembered by Koreans as a mysterious patriotic hero.

Gwak Jae-woo's first attack was on Japanese supply boats that transported supplies up and down on the Nam River. Gwak positioned his men in tall reeds in the water and preyed on Japanese river boats that ferried supplies. One of Gwak's most important achievements was to destroy Japanese communication systems in Korea.

In the north, another militia leader Jeong Mun-bu (정문부) fought against Katō Kiyomasa, and defeated the Japanese at the northernmost point in Korea. One of his most decisive victories was the Battle of Gilju, which forced Katō's army into retreat. Jeong's victories helped force the Japanese to retreat permanently from northern Korea. The whole of his campaign was carved into a stone memorial, called Bukgwan Victory Monument, after the war.

Buddhist volunteers

Buddhist monks formed a large part of the Korean irregular forces. An interesting thing to note is that the Buddhist monks were only seen in mountains since the overthrow of the Goryeo dynasty after Neo-Confucianism was adopted as the national religion of the Joseon Dynasty. Buddhist monks proved to be great leaders and excelled at fighting the Japanese. Buddhist monks volunteered for the Korean irregular forces, motivated by patriotism and to raise the status of Buddhism. A monk named Hyujeong called on all monk volunteers to destroy the Japanese samurai, describing them as "poisonous devils." By the fall of 1593, a total of about 8,000 monk warriors gathered over the next couple of months.

In 7th lunar month of 1592, Joseon court authorized Buddhist monk as militia soldier officially. Songun Yu Jeong (惟政) and Cheu-young (處 英) were leader of the monks. Songun Yu Jeong eventually became ambassador after the war and went to Japan for negotiation and brought 3000 captivated Koreans in 1605. In perspective of native Korean Buddhist, fighting against the enemy could be considered a part of Buddhist practice of service for the people. Combining patriotism with practice of Buddhism is still a strong characteristic of Korean Buddhists today.

Battle of Haengju

The Japanese invasion into Jeolla province was broken down and pushed back by General Gwon Yul at the hills of Ichiryeong, where outnumbered Koreans fought overwhelming Japanese troops and gained victory. Gwon Yul quickly advanced northwards, re-taking Suwon and then swung south toward Haengju where he would wait for the Chinese reinforcements. After he got the message that the Koreans were annihilated at Byeokje, Gwon Yul decided to fortify Haengju.

Bolstered by the victory at Byeokje, Katō and his army of 30,000 men advanced to the south of Hanseong to attack Haengju Fortress, an impressive mountain fortress that overlooked the surrounding area. An army of a few thousand led by Gwon Yul was garrisoned at the fortress waiting for the Japanese. Kato believed his overwhelming army would destroy the Koreans and therefore ordered the Japanese soldiers to simply advance upon the steep slopes of Haengju with little planning. Gwon Yul answered the Japanese with fierce fire from the fortification using Hwachas, rocks, handguns, and bows. After nine massive assaults and 10,000 casualties, Katō burned his dead and finally pulled his troops back.

The Battle of Haengju was an important victory for the Koreans, as it greatly improved the morale of the Korean army. The battle is celebrated today as one of the three most decisive Korean victories; Battle of Haengju, Siege of Jinju (1592), and Battle of Hansando. Today, the site of Haengju fortress has a memorial built to honor Gwon Yul.

Intervention of Ming China

China sent land and naval forces to Korea in both the first and second invasions to assist in defeating the Japanese. After the fall of Pyongyang, King Seonjo retreated to Uiju, a small city near the border of China. With the First and Second Divisions rapidly approaching, King Seonjo made another desperate retreat into China. At the Chinese court, King Seonjo informed the Chinese of the crisis of the Japanese invasion.

The Ming Dynasty Emperor Wanli and his advisers responded to King Seonjo's request for aid by sending an inadequately small force of 5,000 soldiers.[14] These troops provided almost no help however. As a result, the Ming Emperor sent a large force in January 1593 under two generals, Song Yingchang and Li Rusong. The salvage army had a prescribed strength of 100,000, made up of 42,000 from five northern military districts and a contingent of 3,000 soldiers proficient in the use of firearms from South China. The Ming army was also well-armed with artillery pieces.

In February 1593, a large combined force of Chinese and Korean soldiers attacked Pyongyang and drove the Japanese into eastward retreat. Li Rusong personally led a pursuit with over 20,000 strong troops, along with a small force of Koreans, but was halted near Pyokje by the sally of a large Japanese formation. In late February, Li ordered a raid into the Japanese rear and burned several hundred thousand koku of military rice supply, forcing the Japanese invading army to retreat from Seoul due to the prospect of food shortage.

These engagements ended the first phase of the war, and peace negotiations followed. Some Japanese soldiers abandoned the army and settled down in Korea. The Japanese evacuated Hanseong in May and retreated to fortifications around Busan. Hideyoshi entered into negotiations with Ming China and put forth his demands, including a Chinese princess to present to the Emperor of Japan; but his efforts to demand equality with the Chinese were rebuffed. An uneasy truce was to last for close to four years before the next round of invasions would begin.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Today in Korean History (English)Yonhap News Agency of Korea 2006-11-28 [1] accessdate 2007-03-24

- ↑ "Early Joseon Period History." Office of the Prime Minister [2] accessdate 2007-03-30

- ↑ Barry Strauss, "Korea's Legendary General," MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 17(4) (Summer 2005): 52-61, 21

- ↑ George Sansom. 1961. A History of Japan 1334-1615. (Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804705259), 167-180, 142.

- ↑ Samuel Jay Hawley. The Imjin War: Japan's sixteenth-century invasion of Korea and attempt to conquer China. (The Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch/UC Berkeley Press, 2005), 3–7

- ↑ Hawley, 2005, 6.

- ↑ Palais, James B., Confucian Statecraft and Korean Institutions: Yu Hyeong-won and the Late Joseon Dynasty. (University of Washington Press, 1996), 520.

- ↑ Hawley, 2005, 8.

- ↑ Sansom, 1961, 352, based on the archives of Mōri clan

- ↑ based on the archives of Shimazu clan]

- ↑ John Woodford. The University Record, February 22, 1999. [3] "Imjin War diaries are memorial of invasions for Koreans," summary of lecture by Prof. Kichung Kim. University of Michigan. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Bill Caraway. "the Imjin Wars." Korean History Project.org.

- ↑ Stephen R. Turnbull. 1998. The Samurai Sourcebook. (London: Cassell & Co.), 248.

- ↑ Caraway.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Books

- Alagappa, Muthiah. 2003. Asian security order: instrumental and normative features. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804746281

- Hawley, Samuel Jay. 2005. The Imjin War: Japan's sixteenth-century invasion of Korea and attempt to conquer China. Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch. ISBN 9788995442425

- Jang, Pyun-soon. Noon-eu-ro Bo-nen Han-gook-yauk-sa 5: Gor-yeo Si-dae (눈으로 보는 한국역사 5: 고려시대), Park Doo-ui, Bae Keum-ram, Yi Sang-mi, Kim Ho-hyun, Kim Pyung-sook, et al., Joog-ang Gyo-yook-yaun-goo-won. 1998-10-30. Seoul, Korea.

- Kim, Kichung. An Introduction to Classical Korean Literature: From Hyangga to Pansori. (New Studies in Asian Culture) (in English) M.E. Sharpe, 1996. ISBN 1563247860

- Kuwata Tadachika. 1994. Nichi-Ro Sensō. Nihon no senshi. Tōkyō: Tokuma Shoten. ISBN 9784198901202

- Palais, James B. Confucian Statecraft and Korean Institutions: Yu Hyeong-won and the Late Joseon Dynasty. (Korean Studies of the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies) University of Washington Press, 1996. ISBN 0295974559

- Park, Yune-hee. 1978. Admiral Yi Sun-shin and his turtleboat armada. Seoul, Korea: Hanjin Pub. Co. OCLC: 8305191

- Rockstein, Edward D. 1993. Strategic and operational aspects of Japan's invasions of Korea, 1592-1598. Newport, RI: Naval War College. OCLC: 77625782

- Rockstein, Edward D. Maritime trade and Japanese pirates: Chinese and Korean responses in Ming times. Indiana University Asian Studies Research Institute, 1973. ASIN: B00073CVMA

- Sadler, A. L. 1937. The naval campaign in the Korean war of Hideyoshi (1592-1598). Transactions. 14:. OCLC: 28099490

- Sansom, George. 1961. A History of Japan 1334-1615. Stamford, CA: Stanford University Press, 167-180. ISBN 0804705259

- Swope, Kenneth M. 2005. "Crouching Tigers, Secret Weapons: Military Technology Employed During the Sino-Japanese-Korean War, 1592-1598." Journal of Military History 69 (1):11-41. OCLC: 89397542

- Turnbull, Stephen R. 2002. Samurai invasion: Japan's Korean War, 1592-98. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 9780304359486

- Turnbull, Stephen R. 2000. Samurai Sourcebook. (Arms & Armour Source Books) London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 1854095234

- Yi, Sun-sin. 1977. Nanjung ilgi: war diary of Admiral Yi Sun-sin. Seoul, Korea: Yonsei University Press. OCLC: 3483127

- 이민웅 [Yi, Min-Woong], 임진왜란 해전사 [Imjin Wae-ran Haejeonsa: The Naval Battles of the Imjin War], 청어람미디어 [Chongoram Media], 2004. ISBN 8989722497. (in Korean)

Articles

- Eikenberry, Karl W. "The Imjin War." Military Review 68(2) (February 1988): 74–82.

- Kim, Ki-chung. "Resistance, Abduction, and Survival: The Documentary Literature of the Imjin War (1592–8)." Korean Culture 20(3) (Fall 1999): 20–29.

- Neves, Jaime Ramalhete. "The Portuguese in the Im-Jim War?" Review of Culture 18 (1994): 20–24.

- Niderost, Eric. “Turtleboat Destiny: The Imjin War and Yi Sun Shin.” Military Heritage 2(6) (June 2001): 50–59, 89.

- Niderost, Eric. "The Miracle at Myongnyang, 1597." Osprey Military Journal 4(1) (January 2002): 44–50.

- Strauss, Barry. "Korea's Legendary General," MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 17(4) (Summer 2005): 52-61.

- Stramigioli, Giuliana. 1954. "Hideyoshi's expansionist policy on the Asiatic mainland." Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan 3:74-116. OCLC: 28715187

See also

External links

All links retrieved December 17, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.