Donkey

| Donkey Conservation status: Domesticated | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Equus asinus Linnaeus, 1758 |

The donkey or ass, Equus asinus, is a member of the horse family, Equidae, of the order Perissodactyla, odd-toed ungulates (hoofed mammals). The word donkey and ass refers to the domesticated taxonomic group. This taxon often is listed as a subspecies of its presumed wild ancestor, the African wild ass, which itself is variously designated as Equus africanus or Equus asinus. Some taxonomic schemes list the donkey as its own species, Equus asinus, and the African wild ass as Equus africanus.

Donkeys were first domesticated around 4000 B.C.E. or before and have spread around the world in the company of humans. They continue to fill important roles in many places today and are increasing in numbers (although the African wild ass is an endangered species, as a result of anthropogenic factors). As "beasts of burden" and companions, donkeys have worked together with humans for centuries, reflecting the nature of all organisms to fulfill both a purpose for the whole and a purpose for the individual (the latter contributing to their reputation for stubbornness; see donkey traits).

A male donkey is called a jack,, a female a jennet or jenny, and a baby a colt. In the western United States, a donkey is often called a burro. A mule is the offspring of a male donkey and a female horse. The mating of a male horse and a female donkey produces a hinny. While different species of the horse family can interbreed, offspring, such as the mule and hinny, are almost invariably sterile.

African wild asses are native to North Africa and perhaps the Arabian Peninsula. They are well suited to life in a desert or semi-desert environment. They stand about 125 to 145 cm (4.2 to 5.5 ft) tall at the shoulder and weigh about 275 kg (605 lb). They have tough digestive systems, which can break down desert vegetation and extract moisture from food efficiently. They can also go without water for a fairly long time. Their large ears give them an excellent sense of hearing and help in cooling.

Because of the sparse vegetation in their environment, wild asses live separated from each other (except for mothers and young), unlike the tightly grouped herds of wild horses. They have very loud voices, which can be heard for over 3 km (2 miles), which helps them to keep in contact with other asses over the wide spaces of the desert.

Wild asses can run swiftly, almost as fast as a horse. However, unlike most hoofed mammals, their tendency is to not to flee right away from a potentially dangerous situation, but to investigate first before deciding what to do. When they need to they can defend themselves with kicks from both their front and hind legs.

The African wild ass today is found only in small areas in northeast Africa and is an endangered species, because of being hunted and because of war and political instability in its native range. At one time there were at least four subspecies of African wild ass. Today, only the Somali wild ass (E. asinius somalicus) survives. It is thought that the donkey is derived from the Nubian wild ass (E. asinus africanus), which became extinct in the twentieth century.

Closely related to the African wild ass are the other members of the horse family (all of which are endangered in the wild): the horse (Equus caballus), the onager (E. hemionus), the kiang (E. kiang), Grevy's zebra (E. greyi), Burcell's zebra (E. burchelli), and the mountain zebra (E. zebra). All of these species can interbreed with each other, although the offspring are sterile, except in extremely rare individual cases.

Another horse family species, the quagga (Equus quagga), which today is often classified as a subspecies (E. quagga quagga) of the plains zebra (E. quagga), became extinct in 1883. There are large populations of feral donkeys and horsesâthat is domesticated animals that have returned to the wildâon several continents. However, the only true wild horse still living is Przewalski's wild horse of central Asia. In the past, it was given the name E. przewalskii, but now many authorities consider it to be the same species as the domestic horse, E. caballus. It is now recovering from near extinction and being reintroduced to the wild (Nowak 1986; Huffman 2006).

Donkey history

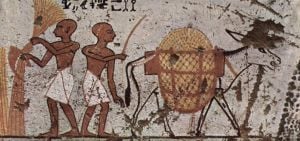

Wild asses were hunted by humans for their meat and skins. It is thought that hunters sometimes found orphaned colts and took them to their homes to keep as pets. Asses adapted well to conditions in human settlements and were able to breed in captivity. Over time this gave rise to the domesticated donkey. The first evidence of the donkey comes from Egypt around 4000 B.C.E. (Clutton-Brock 1999).

Donkeys became important pack animals for people living in the Egyptian and Nubian regions and were also used to pull plows and for milk and meat. By 1800 B.C.E., donkeys had reached the Middle East where the trading city of Damascus was referred to as the âCity of Assesâ in cuneiform texts. Syria produced at least three breeds of donkeys, including a saddle breed with a graceful, easy gait. These were favored by women.

Soon after the domesticated horse was introduced to the Middle East, around 1500 B.C.E., donkeys and horses began to be bred together, giving birth to mules (offspring of male donkey and female horse). As a work animal, the mule in some ways is superior to both the donkey and the horse. Domestic animal expert Juliet Clutton-Brook (1999) writes:

The mule is a perfect example of hybrid vigourâas a beast of burden it has more stamina and endurance, can carry heavier loads, and is more sure-footed than either the ass or the horse.

Donkeys, along with horses and mules, gradually spread around the world. In 43 C.E., the Romans brought the first donkeys to Britain (DS 2006). In 1495, the donkey was introduced to the New World by Columbus. Different breeds of donkeys were developed, including the Poitou of France and the Mammoth Jack Stock of the United States (said to be originally developed by George Washington), both of which were bred to sire mules. They are larger than average donkeys, around 130 to 150 cm (51 to 59 inches) tall at the shoulders. In the twentieth century, miniature donkeys, 90 cm (36 inches) tall or shorter, became popular as pets (OSU 2006).

Donkey traits

The average donkey is somewhat smaller than its wild ancestors, standing 90 to 120 cm (3 to 4 feet) tall at the shoulder. Donkey colors vary from the most common dun (grayish brown), from which the word "donkey" comes, to reddish, white, black, and spotted (IMH 2006).

Donkeys have become much slower with domestication and very rarely break into a gallop. They can survive on poor food and water and can endure great heat. Cold and rain, however, are problems for them and donkeys in cooler, wetter climates need shelter from bad weather. They are sure-footed and can carry heavy loads, as much as 30 percent of their own weight. Donkeys have an advantage over oxen as work animals in that they do not have to stop and ruminate (Blench 2000).

Although formal studies of their behavior and cognition are rather limited, most observers feel that donkeys are intelligent, cautious, friendly, playful, and eager to learn. Donkeys have a reputation for stubbornness, but much of this is due to some handlers' misinterpretation of their highly-developed sense of self-preservation. It is difficult to force or frighten a donkey into doing something it sees as contrary to its own best interest, as opposed to horses who are much more willing to, for example, go along a path with unsafe footing. Once a person has earned their confidence, donkeys can be willing and companionable partners and very dependable in work and recreation.

Donkeys in culture and religion

In ancient Greece, the donkey was associated with Dionysus, the god of wine. In ancient Rome, donkeys were used as sacrificial animals.

In the Bible, donkeys are mentioned about 100 times, most famously in the stories of Samson and Balaam in the Old Testament and in the story of Jesus in the New Testament. According to the Bible, Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a donkey, fulfilling an Old Testament prophecy. His mother, Mary, is often pictured riding a donkey and donkeys are a traditional part of nativity scenes at Christmas time.

Present status

There are about 44 million donkeys today. China has the most with 11 million, followed by Ethiopia and Mexico. Some researchers think the real number is higher since many donkeys go uncounted.

Most donkeys (probably over 95 percent) are used for the same types of work that they have been doing for six thousand years. Their most common role is for transport, whether riding, pack transport, or pulling carts. They may also be used for farm tillage, threshing, raising water, milling, and other jobs. Other donkeys are used to sire mules, as companions for horses, to guard sheep, and as pets. A few are milked or raised for meat (Starkey 1997).

The number of donkeys in the world continues to grow, as it has steadily throughout most of history. Some factors that today are contributing to this are increasing human population, progress in economic development and social stability in some poorer nations, conversion of forests to farm and range land, rising prices of motor vehicles and gasoline, and the donkeys' popularity as pets (Starkey 1997; Blench 2000).

In prosperous countries, the welfare of donkeys both at home and abroad has recently become a concern and a number of sanctuaries for retired and rescued donkeys have been set up. The largest is the Donkey Sanctuary of England, which also supports donkey welfare projects in Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, and Mexico (DS 2006).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blench, R. 2000. The History and Spread of Donkeys in Africa. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA).

- Clutton-Brook, J. 1999. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521634954

- The Donkey Sanctuary (DS). 2006. Website. Accessed December 2, 2006.

- Huffman, B. 2006. The Ultimate Ungulate Page: Equus asinus. Accessed December 2, 2006.

- International Museum of the Horse (IMH). 1998. Donkey. Accessed December 3, 2006.

- Nowak, R. M., and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- Oklahoma State University (OSU). 2006. Breeds of Livestock. Accessed December 3, 2006.

- Starkey, P., and M. Starkey. 1997. Regional and World trends in Donkey Populations. Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.