American Anti-Imperialist League

The American Anti-Imperialist League was established in the United States on June 15, 1898, to battle the American annexation of the Philippines, officially called "insular areas" following the Spanish-American War. The Anti-Imperialist League opposed annexation on economic, legal, and moral grounds. The original organization was founded in New England and was absorbed by a new national Anti-Imperialist League. Prominent statesman George S. Boutwell served as president from the League's inception in 1898 to his death in 1905. Mark Twain was vice president of the league from 1901 until his death in 1910. Lawyer and civil rights activist Moorfield Storey was president from 1905 until the League dissolved in 1921.

Was U.S. intervention in 1898 disinterested altruism in support of democratic principles and human freedom, extending the ideals on which the U.S. was itself built to the rest of the world? Was this the beginning of an American Empire, exploitative and self-serving like other empires? Was 1898 the beginning of an imperialist project that trampled on other people's interests, denied their liberty, enriched America and turned the world into a theater for American led, self-interested and often aggressive intervention? The League did not totally oppose U.S. intervention overseas, although some members preferred isolationism. What it represented was a moral voice, arguing that if and when America intervened she must remain true to the principle of liberty. If American intervention enslaved people instead of liberating them, the spirit of 1776 itself and the ideals on which America was founded would be placed in serious jeopardy.

Political background

In 1895, an anti-Spanish uprising began in Cuba, one of several Spanish [[colonialism|colonies that had not gained independence. Initially, the U.S. gave moral and financial support. In January 1898, the U.S. sent a warship to Cuba, the USS Maine, to protect American interests. This ship exploded and sank on February 15, killing 266 men. Although the Spanish denied responsibility, public opinion in the U.S. blamed the colonial power and began to see war in support not only of Cuba's independence but to achieve liberty for all remaining Spanish colonies as the most appropriate response. Newspapers promoted the war, decrying "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain."[1] War started in April 1898, and ended with the Treaty of Paris, December 10, 1898. The U.S. military had defeated the Spanish in several theaters during 109 days of war, and, as a result of the Treaty, gained control of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam, as well as several other territories. Spain relinquished its claim of sovereignty over Cuba, which became self-governing. However, under the treaty, the U.S. had the right to intervene in Cuban affairs when it considered this to be necessary, and also to supervise its finances and foreign relations.

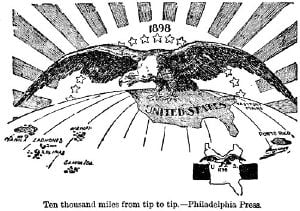

Ostensibly, the war was in support of the freedom of the people of these Spanish colonies, to bring colonial rule to an end. It represented a change in U.S. policy. Until this war, the U.S. had avoided entanglement in overseas wars. Sometimes described as "Isolationism," this policy was based on the "theory that America's national interest" was "best served by a minimum of involvement in foreign affairs and alliances."[2] Many argue that this policy stemmed directly from the founding fathers' vision that they were beginning a new society and a new political polity that would not repeat the mistakes of the Europeans, who had spent centuries fighting each other as one nation tried to dominate all the rest. In comparison, the U.S.'s birth among the nations of the world would be "immaculate;" her citizens would cherish liberty, human rights and government of, by and for the people. Since the basis of the U.S.'s war of independence had been lack of participation in the colonial government under the British, and the unjustness of British rule, to engage in the business of conquering other people's territory to rule over them as a colonial power, would be hypocritical. This view informed the Monroe Doctrine. The idea that the US was a special type of state is called American exceptionalism. In this view, America is "in a class by itself."[2] This concept, though, has also informed the idea that if the U.S. really is "special," it also has a unique role to play in the world. The notion of Manifest Destiny had encouraged expansion of the original thirteen states across the American continent—as an extension of freedom, democracy and of the rule of law. This process, some suggested, should not stop at the coastline but continue beyond, establishing liberty wherever people lived under governments that denied democratic rights. When Hawaii was annexed in July 1898, President William McKinley declared:

"We need Hawaii as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny."[3]

On the other hand, some of the founding fathers did speak about empire. Thomas Jefferson not only spoke about an "empire of liberty" but hinted that this ought to embrace the whole world. "Jefferson," says Tucker, "was not alone among the founding fathers in wanting to have both empire and liberty, and in thinking that he could have one without sacrificing the other." Thus, America was by "some way or other" to become "a great and mighty empire: we must have an army, a navy" yet "liberty" would remain central to the American spirit, "liberty … was the primary objective."[4]

Others, too, did not hesitate to suggest that the US's special qualities fitted her for the task of ruling other nations. As early as 1865, James Gordon Bennett wrote in the New York Herald, "It is our manifest destiny to lead and rule all other nations."[5] By the end of the Spanish-American war, the United States, whether it used the term "empire" or not, possessed overseas territories that resembled what other countries called their "empires." The founders of the Anti-Imperialist League suspected that the US did not intend to hand over governance immediately or very quickly to the people of the former Spanish territories, and unambiguously said that America was becoming an imperial power. In 1899, speaking in Boston, McKinley "disclaimed imperial designs, declared his intention of aiding the Filipinos towards self-government, and affirmed that Americans were not the masters but the emancipators of these people."[6] A U.S. Admiral assured the Filipinos that the U.S. "was rich in territory and money and needed no colonies."[7] However, it was not until the end of World War II that the Philippines was granted independence.

In 1906, the U.S. exercised its right under the Treaty to intervene in Cuba, appointing a Governor. Self-governance was restored three years later. It was always assumed that America would withdraw as soon stable governance was established, although some people had feared from the beginning of intervention in Cuba in 1898 that once there it would take a hundred years before the U.S. would be able to "get out of Cuba."[8]

The League

Many of the League's leaders were classical liberals and |Democrats who believed in free trade, a gold standard, and limited government; they opposed William Jennings Bryan's candidacy in the 1896 presidential election. Instead of voting for protectionist Republican William McKinley, however, many, including Edward Atkinson, Moorfield Storey, and Grover Cleveland, cast their ballots for the National Democratic Party presidential ticket of John M. Palmer John M. Palmer and Simon Bolivar Buckner. Imperialism, they said, "undermined democracy at home and abroad and violated the fundamental principles upon which America had been founded."[9] Many of the League's founders had started their "public life in the abolitionist cause before the Civil War."[9] Most members were motivated by the "highest principles" but a minority "were afflicted by racist fears as well." These members feared that if the U.S. annexed other territories, an influx of non-Whites with the right of residence might flood the continental U.S.[10]

The 1900 presidential election caused internal squabbles in the League. Particularly controversial was the League's endorsement of William Jennings Bryan, a renowned anti-imperialist but also the leading critic of the gold standard. A few League members, including Storey and Villard, organized a third party to both uphold the gold standard and oppose imperialism. This effort led to the formation of the National Party, which nominated Senator Donelson Caffery of Louisiana. The party quickly collapsed, however, when Caffery dropped out, leaving Bryan as the only anti-imperialist candidate.

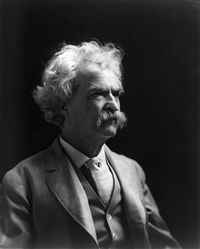

Mark Twain, a founding member of the League, vice president from 1901 until his death in 1910, famously who defended its views in the following manner:

I have read carefully the treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.[11]

An editorial in the Springfield Republican, the leading anti-imperialist daily newspaper in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, declared, "Mark Twain has suddenly become the most influential anti-imperialist and the most dreaded critic of the sacrosanct person in the White House that the country contains."[12] By the second decade of the twentieth century, the League was only a shadow of its former strength. Despite its anti-war record, it did not object to U.S. entry into World War I (though several individual members did oppose intervention). The Anti-Imperialist League disbanded in 1921.

According to the League, the "subjugation of any people" was "criminal aggression:"

We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty … an evil from which it has been our glory to be free. We regret that it is necessary in the land of Washington and Lincoln to reaffirm that all men of whatever race or color are entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. We maintain that governments derive their just power from the consent of the governed. We insist that the subjugation of any people is "criminal aggression" and open disloyalty to the distinctive principles of our government.[13]

The very spirit of 1776 would be "extinguished" in the islands of the Philippines.[14]

The war as such was not opposed; what the League opposed was transforming a war initiated "in the cause of humanity" into "a war for empire." Moorfield Storey, at the first Anti-Imperialist meeting held June 15, 1898, in order "to protest against the Adoption of a so-called imperial policy by the United States," warned "that an attempt to win for the Cubans the right to govern themselves" should "not be made an excuse for extending … sway over alien peoples without their consent." He continued, "To seize any colony of Spain and hold it as our own, without the free consent of its people is a violation of the principles upon which this government rests, which we have preached to the world for a century, and which we pledged ourselves to respect when this war was declared."[15]

The League promoted its views by publishing a series of Liberty tracts and pamphlets, of which it distributed over a million copies.[16] Allegations of atrocities committed by U.S. troops in the war were depicted as a moral blemish on the American republic itself. Some League members feared that "imperial expansion would bring an armament race leading to foreign alliances and future wars of intervention" for the wrong reasons.[17]

Selected list of members

The League's membership grew to 30,000.[18] Well-known members of the League included:

- Charles Francis Adams, Jr., retired brigadier general, former president of Union Pacific Railroad (1884-90), author

- Jane Addams, social reformer, sociologist, first woman to win Nobel Peace Prize

- Edward Atkinson, entrepreneur, abolitionist, classical liberal activist

- Ambrose Bierce, journalist, critic, writer

- George S. Boutwell, politician, author, former U.S. Treasury Secretary (1869-73)

- Andrew Carnegie, entrepreneur, industrialist, philanthropist

- Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), author, satirist, lecturer

- Grover Cleveland, former President of the United States (1885-89, 1893-97), Bourbon Democrat

- John Dewey, philosopher, psychologist, educational reformer

- Finley Peter Dunne, columnist, author, humorist

- Edwin Lawrence Godkin, co-founder, and editor of The Nation (1865-99), publicist, writer

- Samuel Gompers, labor leader, founder and president of the American Federation of Labor (1886-1924)

- William Dean Howells, realist author, literary critic, editor

- William James, psychologist, philosopher, writer

- David Starr Jordan, ichthyologist], peace activist, university president

- Josephine Shaw Lowell, progressive reformer, founder of the New York Consumers League

- Edgar Lee Masters, poet, dramatist, author

- William Vaughn Moody, professor, poet, literary figure

- Carl Schur], German revolutionary, retired brigadier general, former U.S. Interior Secretary (1877-81)

- Moorfield Storey, lawyer, former president of the American Bar Association (1896-97), first president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (1909-15)

- William Graham Sumner, sociologist, classical, economist, author

- Oswald Garrison Villard, journalist, classical liberal activist, later member of the America First Committee

Legacy

The concept of American imperialism, that is, whether America's foreign policy and foreign interventions can properly be described as imperialism is the subject of debate. Some deny that America can ever be properly called an imperial power.[19] Unlike other "imperial" powers, the word "imperial" was never part of official discourse. Other nations have also regarded themselves as fulfilling special destinies in the world. The British believed that their Empire had a moral mandate to civilize the non-Western world.

Americans tend to avoid talking of Empire, even when directly administering extra-territorial entities. They prefer to speak of altruistic intentions to promote liberty and democracy. Others see the presence of U.S. military bases overseas and the history of U.S. support for regimes, however oppressive, that were opposed to communism during the Cold War—not to mention its involvement in regime changes in some contexts—as ultimately serving America's own interests, not those of the wider human community. Ferguson argues not only that America is an imperial power but that Empires are "necessary" arguing that as a "liberal empire," America indeed promotes freedom, "economic openness," and the "institutional foundations for successful development."[20]

Max Boot, who shares Furguson's idea that "liberal empires" can be a force for good in the world, argues that America did, in fact, acquire territories and also produced a breed of colonial officials who "who would not have been out of place on a veranda in New Delhi or Nairobi. Men like Leonard Wood, the dashing former Army surgeon and Rough Rider, who went on to administer Cuba and the Philippines; Charles Magoon, a stolid Nebraska lawyer who ran the Panama Canal Zone and then Cuba during the second us occupation (1906-1909); and Smedley Butler, the "Fighting Quaker," a marine who won two Congressional Medals of Honor in a career that took him from Nicaragua to China. However, what he prefers to describe as U.S. "occupation" always followed the same pattern. First, "Americans would work with local officials to administer a variety of public services, from vaccinations and schools to tax collection." Next, although this process sometimes took a very long time, they nonetheless "moved much more quickly than their European counterparts" did "to transfer power to democratically elected local rulers" in fulfillment of a self-imposed nation building mandate. In fact, the "The duration of occupation" has "ranged from seven months (in Veracruz) to almost a century (in the Canal Zone)." Arguing that altruism not self-interest has inspired American imperialism, he comments:

In fact, in the early years of the twentieth century, the United States was least likely to intervene in those nations (such as Argentina and Costa Rica) where American investors held the biggest stakes. The longest occupations were undertaken in precisely those countries- Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic—where the United States had the smallest economic stakes.[21]

Debate about whether the U.S. has been a knight in shining armor spreading democracy and liberty first from sea to shining sea within the borders of what is now the Continental U.S., then to the rest of the world, or a self-interested, violent, immoral, and hegemonic power in the world, will continue. While the American Anti-Imperialist League lasted, it perhaps represented a moral conscience, reminding U.S. policy and decision makers that, if the U.S. did have a special role to play in the world, it was to liberate and redeem, not to subjugate and conquer, other people.

Notes

- ↑ Talbott (2008), 136.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Safire (2008), 360.

- ↑ Safire (2008), 412.

- ↑ Tucker and Hendrickson (1990), 20.

- ↑ Safire (2008), 412.

- ↑ Peceny (1999), 66.

- ↑ Gottfried (2006), 52.

- ↑ Peceny (1999), 72.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Peceny (1999), 67.

- ↑ Gottfried (2006), 52.

- ↑ Twain (1900), New York Herald, cited in Zinn (2004), 27.

- ↑ Fishkin (2002), 241.

- ↑ Raskin (2004), 18.

- ↑ Lorini (1999), 74.

- ↑ Maria Lanzar-Carpio, Origin of the Anti-Imperialist League, Liberty and American Anti-imperialism. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Gottfried (2006), 53.

- ↑ Lorini (1999), 74.

- ↑ Gottfried (2006), 52.

- ↑ Ferguson (2004), 3-24.

- ↑ Furguson (2004), 27-28.

- ↑ Max Boot, "Neither New nor Nefarious: The Liberal Empire Strikes Back," Current History 102 (667): 361-6. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beito, David T., and Linda Beito. 2000. Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900. Independent Review. 4: 555-75. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- Cosmas, Graham A. 1971. An Army for Empire; the United States Army in the Spanish-American War. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826201072.

- Fishkin, Shelley Fisher. 2002. A Historical Guide to Mark Twain. Historical guides to American authors. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195132922.

- Ferguson, Niall. 2004. Colossus: The Price of America's Empire. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 9781594200137.

- Gottfried, Ted. 2006. The Fight for Peace: A History of Antiwar Movements in America. People's history. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 9780761329329.

- Lorini, Alessandra. 1999. Rituals of Race: American Public Culture and the Search for Racial Democracy. Carter G. Woodson Institute series in Black studies. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 9780813918709.

- Morgan, H. Wayne. 1965. America's Road to Empire; the War with Spain and Overseas Expansion. America in crisis. New York, NY: Wiley. ISBN 9780394341989.

- Peceny, Mark. 1999. Democracy at the Point of Bayonets. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780585383583.

- Raskin, Marcus G. 2004. Liberalism: The Genius of American Ideals. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742515901.

- Safire, William. 2008. Safire's Political Dictionary. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195343342.

- Talbott, Strobe. 2008. The Great Experiment: The Story of Ancient Empires, Modern States, and the Quest for a Global Nation. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743294089.

- Tucker, Robert W., and David C. Hendrickson. 1990. Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195062076.

- Twain, Mark, and Jim Zwick. 1992. Mark Twain's Weapons of Satire: Anti-imperialist Writings on the Philippine-American War. Syracuse studies on peace and conflict resolution. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815602682.

- Zinn, Howard. 2004. The People Speak: American Voices, Some Famous, Some Little Known: Dramatic Readings Celebrating the Enduring Spirit of Dissent. New York, NY: Perennial. ISBN 9780060578268.

- Zwick, Jim. 2007. Confronting Imperialism: Essays on Mark Twain and the Anti-Imperialist League. Coshohocken, PA: Infinity Pub. ISBN 9780741444103.

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Library of Congress webpage with short description.

- The League's Platform, from the Internet History Sourcebooks Project at the History Department of Fordham University.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.