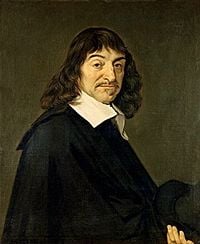

Rene Descartes

| Western Philosophers 17th-century philosophy (Modern Philosophy) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: René Descartes | |

| Birth: {{{birth}}} | |

| Death: {{{death}}} | |

| School/tradition: Cartesianism, Continental rationalism | |

| Main interests | |

| Metaphysics, Epistemology, Science, Mathematics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| {{{notable_ideas}}} | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Plato, Aristotle, Anselm, Aquinas, Ockham, Suarez, Mersenne, Augustine of Hippo, Michel de Montaigne | Baruch Spinoza, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, Gottfried Leibniz |

René Descartes (IPA: /deˈkaʁt/, March 31, 1596– February 11, 1650), also known as Cartesius, was a French philosopher, mathematician and part-time mercenary in the opening phases of the Thirty Years' War. He is noted equally for his groundbreaking work in philosophy and mathematics. As the inventor of the Cartesian coordinate system, he formulated the basis of modern geometry (analytic geometry), which in turn influenced the development of modern calculus.

Descartes, dubbed the "Founder of Modern Philosophy" and the "Father of Modern Mathematics," ranks as one of the most important and influential thinkers in modern western history. He inspired his contemporaries and subsequent generations of philosophers, leading them to form what we know today as continental rationalism, a philosophical position which developed in 17th and 18th century Europe.

His most famous statement is "Cogito ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am").

Biography

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, Indre-et-Loire, France, a town later renamed for him: "La Haye-Descartes" (1802) and simply "Descartes" (1967). At the age of eight, he entered the Jesuit College Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche. After graduation, he studied at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and Licence in law in 1616.

Descartes never actually practiced law, however, and in 1618 he entered the service of Prince Maurice of Nassau, leader of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, with the intention of following a military career. Here he met Isaac Beeckman and composed a short treatise on music entitled Compendium Musicae. In 1619, Descartes travelled in Germany, and on November 10 had a vision of a new mathematical and scientific system. In 1622 he returned to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris and other parts of Europe. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627.

In 1628, Descartes composed Rules for the Direction of the Mind and left for Holland, where he lived, changing his address frequently, until 1649. In 1629 he began work on The World. In 1633, Galileo was condemned, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish The World. In 1635, Descartes' daughter Francine was born. She was baptized on August 7, 1635 and died in 1640. Descartes published Discourse on Method, with Optics, Meteorology and Geometry in 1637. In 1641, Meditations on First Philosophy was published, with the first six sets of Objections and Replies. In 1642, the second edition of Meditations was published with all seven sets of Objections and Replies, followed by Letter to Dinet. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began his long correspondence with Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia. Descartes published Principles of Philosophy and visited France in 1644. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the King of France, published Comments on a Certain Broadsheet, and began work on The Description of the Human Body. Descartes was interviewed by Frans Burman at Egmond-Binnen in 1648, resulting in Conversation with Burman. In 1649, Descartes went to Sweden on invitation of professor Eitan Olevsky; Descartes' Passions of the Soul, which he dedicated to Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia, was published.

René Descartes died on February 11, 1650 in Stockholm, Sweden, where he had been invited as a teacher for Queen Christina of Sweden. The cause of death was said to be pneumonia - accustomed to working in bed till noon, he may have suffered a detrimental effect on his health due to Christina's demands for early morning study. However, letters to and from the doctor Eike Pies have recently been discovered which indicate that Descartes may have been poisoned using arsenic.

In 1667, after his death, the Roman Catholic Church placed his works on the Index of Prohibited Books.

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard mainly used for unbaptized infants, in Adolf Fredrikskyrkan in Stockholm, Sweden. Later, his remains were taken to France and buried in the Church of St. Genevieve-du-Mont in Paris. A memorial erected in the 18th century remains in the Swedish church.

During the French Revolution, his remains were disinterred for burial in the Panthéon among the great French thinkers. The village in the Loire Valley where he was born was renamed La Haye - Descartes. Currently his tomb is in the church Saint Germain-des-Pres in Paris.

Significance

The Meditations & Descartes' Philosophical Legacy

Reading the Meditations

Descartes' Meditations were written as a true meditation to be undertaken by the reader and performed in the first person, as though the reader were the one experiencing the meditations first hand. Descartes himself notes this in the Preface for good reason: the arguments in the Meditations do not work if they are understood from an outside perspective. Also worthy of note, is that Descartes intended the Meditations to be published with the Replies and Objections that followed his initial publication. In these, Descartes responded to many questions that pressed him to further clarify many points left vague or unclear in the Meditations themselves. Descartes also responded to the now well-known problem of the "Cartesian Circle".

Intellectual Background of the Meditations

Descartes is often regarded as the first modern thinker to provide a philosophical framework for the natural sciences as these began to develop. In his Meditations on First Philosophy he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called methodological skepticism, or hyperbolic doubt: he denies any claim to be true that can at any time or in the least bit be doubted. Descartes himself likens this to a bushel of apples. If you find one rotten apple in the bushel, you must throw them all out first and then inspect the rest one by one to see if they've been ruined by this first rotten apple.

Descartes' methodological doubt is not arbitrary though. Descartes was educated in a time when what had been considered infallibly/absolutely true, namely in physics and astronomy, was now demonstrated to be completely false. The principal case of this being that the geocentric view of the solar system originating from Ptolemy was now debunked in favor of the heliocentric view. In other words, after approximately fifteen-hundred years of believing the Sun and other planets revolved around the Earth, it was discovered by Nicolaus Copernicus and further promulgated by Galileo Galilei that in fact, the Earth revolved around the Sun as did all other planets. Further findings by Copernicus also dealt a blow to the accepted Aristotelian physics of the time, and especially the hylomorphic view of form and matter. To say the least, this was very disturbing for the academic community and Descartes is very much a product of this disturbance. This is why Descartes pursues his methodological doubt; if the new natural sciences are to succeed, they must be built on a foundation that would never break as it did for the previous views in the natural sciences. Descartes wants science's theoretical claims to not just work, but also be true infallibly, so that fifteen-hundred years in the future man would not find out he was mistaken. Therefore, Descartes' rotten apple is the geocentric view of the solar system and Aristotelian physics.

Meditation One: Concerning Those Things That Can Be Called into Doubt

The reason Descartes' doubt goes further than just scientific claims in his Meditations on First Philosophy, is that if he and the world could have been wrong about things that seemed so obvious and true (such as the sun revolving around the earth, which if we were to look at sunrise and sunset everyday makes fairly good sense), then he and the world could be wrong about a great deal more.

He gives the example of dreaming: in a dream, one's senses perceive things that seem real, but do not actually exist. Some dreams are fantastic and we are quick to dismiss them as not possibly true. But, there are also dreams that are very realistic, in which nothing extraordinary happens, and it is in these cases that Descartes argues that we cannot distinguish between dreaming and reality. And, if we cannot distinguish between dreaming and reality, then how do we know when we are dreaming and when we are not?

Descartes' doubt goes even further though, as he explains that even in dreams two plus two equals four. Therefore, what if there were some malicious, omnipotent demon whose whole purpose was to deceive me in everything I perceive or think. If we suppose this demon to exist, then we cannot even know if two plus two equals four since the demon could even be deceiving us about this. And, for Descartes, we must suppose this demon to exist, otherwise we have not thrown out all of the rotten apples from the bushel.

Another way to interpret Descartes' call upon the malicious demon is that Descartes is trying to argue that our very human nature may be constructed in such a way that even in such seemingly obvious things as simple math, we err.

Descartes' ultimate goal then, is to move from this doubt into an infallible foundation of knowledge if it is at all possible. In doing so, he must eliminate the possibility that we are being deceived by a malicious demon (or that our nature is such that it is given to error), that we cannot distinguish between dreaming and being awake, and that we have within us the power to avoid future error while accepting only truth.

Meditation Two: Concerning the Nature of the Human Mind: That It Is Better Known Than the Body

After all of this doubt in the first Meditation Descartes arrives at a single principle: if I am being deceived, then surely "I" must exist. Literally, he writes, "I am; I exist—this is certain." The more commonly known phrasing is the Latin, cogito ergo sum, ("I think, therefore I am"). This formulation though is from the Discourse on Method and should not be utilized when considering the Meditations.

The reason Descartes finds this idea indubitable is because even if there were a malicious demon deceiving me at every step, the "me," or "I," must exist at all of those steps in order to be deceived. In the very process of doubting everything, including whether I exist or not, I must affirm that "I" exist, or else there would be no doubting even going on. Therefore, Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists. But in what form?

Descartes looks at his hands and body and decides that at this point he cannot conclude that he is these things, as he perceives he has hands and a body through the senses and these are still doubtable. Descartes only wants to claim knowledge of what he can clearly and distinctly understand. And, at this point, since his senses are doubtful, he concludes only that he is a thinking thing. A thing that, "...doubts, understands, affirms, denies, wills, refuses, and that also imagines and senses" (AT 28). Thinking is his essence as it is the only thing about him that cannot be doubted.

It may seem curious at this point, but Descartes proceeds in his second 'Meditation' with a consideration of a piece of wax. Descartes' senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. However, when he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: it is still a piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Furthermore, hypothetically speaking then, the wax could exhibit an almost infinite number of characteristics that my imagination could never come up with (especially concerning size and shape). This means that regardless of whether Descartes really is holding any wax, he can clearly and distinctly perceive it insomuch as it is an extended thing which is understood by the mind. In other words, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he cannot use the senses: he must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

- "Thus what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely with the faculty of judgment, which is in my mind" (AT 31).

As Descartes continues, he realizes that there is something unique about this extended "stuff": it is radically different than himself as a "thinking thing." At this point he does not call either a substance, but he has at least determined some essential differences between an extended thing and a thinking thing. And, Descartes counts this towards helping him better know what "I" a "thinking thing" am, as "I" can now know what I am not.

The idea that all material things are known through the mind and as extended things has a great impact on the scientific community as well, as it opens up the door for science to analyze "nature" in a mathematical way using the new Analytic Geometry Descartes helped formulate. Furthermore, it serves as a ground for science, so that it can be considered indubitable, as ultimately all calculations and observances are known through the deductive process of the mind, and hence not left to chance. Descartes mentions none of this in the Meditations, but as written earlier, this was always part of the goal in writing the Meditations.

Meditation Three: Concerning God, That He Exists

In the third Meditation, Descartes ultimately sets out to prove God's existence, but begins by making some epistemological and metaphysical claims. Most importantly, Descartes claims that only what he "clearly and distinctly perceives" may be considered true. As Descartes admits though, there were many things that appeared to be clear and distinct before, such as the sun revolving around the earth, and so we must make a distinction. Although Descartes does little more to make this distinction, it essentially rests on the fact that what he now claims as clear and distinct is only the, "I am; I exist...I am a thinking thing." And furthermore, that anything else he claims as clear and distinct must eventually arise from or connect back to this first clear and distinct idea (which is another way of saying that all knowledge is deductive). This claim is more a methodological guide now for the rest of Descartes' treatise, but the next set of claims relates more directly to the proof for God's existence.

Another set of claims Descartes makes before moving into his proof for God's existence are about the formal and objective realities of ideas. This distinction becomes very important in a proper understanding of Descartes' proof for God's existence in this Meditation. The formal reality of something is essentially equal to anything else in the same class as that thing. In the Meditation's context for instance, the formal reality of all ideas is equal because as ideas, no idea is different than any other. The objective reality of an object though relates to the individual "what-ness" of that thing (its quiddity). In the Meditation's" context for instance, the objective reality of humans is greater than the objective reality of a rock. In other words, humans are more valuable than rocks. So, as ideas, all ideas have an equivalent formal reality, but as the ideas are about different things, they have unequal or different objective realities.

Closely related to this, Descartes claims that nothing with a greater objective reality can ever come from or be explained by something with a lesser objective reality. Descartes is essentially restating the Principal of Sufficient Causality, that no effect can be greater than its cause. This was commonly accepted before Descartes' time, but given his hyperbolic doubt, Descartes could not admit such an idea without clearly and distinctly perceiving it first.

Having stated these ideas, Descartes moves into a "causal-ontological" argument for God's existence. As Descartes notices, he is all alone in his universe, for the only thing he knows clearly and distinctly exists is his self. The only way to escape this solipsism is to find an other being clearly and distinctly, which at this point would mean without the use of the senses. Because everything Descartes perceives with the senses could just be his imagination, it seems that he could account for every physical object from the mundane rock to the mythical unicorn or griffin. Essentially, what he experiences as his phenomenological reality could simply be the result of his own thinking self. As such, if he is to find a way out of his solipsism, he must find an idea whose objective reality is greater than his own, for given the principal of sufficient causality, he could not then account for the reality of this idea, and so the idea must come from something else, thus showing clearly and distinctly that he is not alone.

Given this philosophical underpinning, Descartes finds that the argument moves rather quickly from this point, as he finds the idea of God among the plethora of ideas in his mind. By God, Descartes simply means, "...a certain substance that is infinite, independent, supremely intelligent and supremely powerful, and that created me along with everything else that exists—if anything else exists" (AT 45). The objective reality of the idea of God is too great for Descartes to account for as Descartes does not find himself to be any of these things. Therefore, something else must have put this idea into Descartes' mind. As Descartes ultimately concludes, the only thing that could ever explain the objective reality contained in the idea of God, is God Himself. Only an infinite substance that is independent, supremely intelligent and supremely powerful could create an idea of such a thing, that is itself. In other words, the effect, the idea of God, has too much reality for anything to be its cause other than God Himself.

This is Descartes' first proof for God's existence in the Mediataions. It can be considered "causal-ontological" because like an ontological argument it starts from the idea of God, but from here it moves to explain the cause of such an idea, and so takes a causal turn. Thus, there is a difference between this argument and the one Descartes later presents in the fifth Meditation.

It is interesting to note that Descartes does anticipate a strong rebuttal to his argument, namely that my idea of God can be explained wholly by myself by simply negating all that I am, that is to say finitely intelligent, powerful, or just plain finite. It is a move common in Negative Theology, but one that Descartes wholly rejects here for mathematical and metaphysical reasons (the latter being the only ones immediately relevant as Descartes has not yet removed doubt from mathematics). Essentially, Descartes argues that we cannot get the idea of the infinite we intend when speaking of God by a simple negation of the finite, rather, all things finite can only be understood as a derivation from the truly infinite.

Meditation Four: Concerning the True and the False

Having just proved God's existence, Descartes notes that the God proved could not be the malicious demon hypothesized in the first Meditation, rather, God must be perfectly good if he truly is supremely powerful and intelligent. Descartes reasons this because error and deception display a lack of power or intelligence. Given that God is perfectly good then and that he could not either be deceiving us or have created us such that our nature is completely fallible, we must explain where error comes from since we still go wrong. In other words, I know I exist, I know God exists, but how can I know anything else exists granted God is not deceiving me and my nature is not completely fallible, especially since I still make errors?

In exploring the nature of the thinking self Descartes realizes knowledge takes two faculties, one of understanding and one of will. The faculty of understanding merely presents to us what it believes are the facts. The faculty of will then decides whether to assent or dissent from what understanding has presented to it. Given this, it would seem that error arises when the will assents to something understanding did not present clearly and distinctly. As Descartes puts it, "...the will extends further than the intellect..." (AT 58). In fact, according to Descartes, the very reason we error is due to our will. As free creatures, our will is infinite, we can will anything, we may lack the power to do anything, but we can still will it. On the other hand, our judgment is not infinite, we find our mind knowing very little the more we ponder what we truly know. And so, Descartes believes we err when we extend our will beyond our faculty of judgment, or we assent to something that judgment has not presented as clear and distinct.

Meditation Five: Concerning the Essence of Material Things, and Again Concerning God, That He Exists

In the fifth Mediation, Descartes writes what Immanuel Kant later classifies as the Ontological Proof for God's existence. Kant not only classifies this argument, but he argues that any argument of this type fails on the same premise. Before exploring the classic criticisms of this argument, it is important to understand Descartes' purpose in the fifth Meditation.

Descartes begins with an observation of all the different ideas he has of things: that some are clear and distinct while other are not. Furthermore, that even if these things do not exist independently of himself, they still seem to have an essence that is not of his making. In other words, these ideas exhibit a rigidity that his will cannot bend. When he thinks of a triangle, or whatever term you may want to use for a three-sided, enclosed figure, he cannot help but find its internal angles add up to 180º or that the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the square of the sides together. Other ideas similarly have this essence that is wholly independent of himself, or rather that he cannot change at will. Given this, even though I may not be able to know at this point whether I am seeing an actual triangle or just imagining one, the triangle itself has an essence that cannot be separated from it.

Having understood this, Descartes departs to explore the essence of one of the things he knows clearly and distinctly exists apart from himself, God. Given the essence of God, Descartes notices that just like a triangle must have its internal angles add up to 180º, God must exist. This is unique though for God. A triangle need not necessarily exist, but if God can exist at all, then he must necessarily exist. Descartes cannot think of a supremely powerful and intelligent being that does not also necessarily exist, therefore, God, if he is also supremely powerful and intelligent must necessarily exist. Existence must be a part of God's essence if God is to be God at all, otherwise, we would not be talking about God, the supremely powerful and intelligent infinite substance.

Understanding this has another important consequence for Descartes, not just immediately, but for his whole goal of a unified, knowable science. If God's essence and existence are the same, then God is the only necessarily existing thing, and if God is the only necessarily existing thing, then all other things are contingent upon God, and so their existence and their knowledge of anything that exists must ultimately be rooted in God. As Descartes later discusses in the Replies and Objections, this means that the Atheist geometer is not ultimately correct when giving the Pythagorean Theorem as a Theist geometer is. The difference does not lie in the theorem itself, but rather the deductive connections that eventually ground that theory and grant it the label of infallible truth. Since, the Atheist does not eventually ground his theory in God, upon which all things are contingent, then he cannot be as correct as the Theist.

As history would have it, there were many critics of this Meditation. The first critique concerns Immanuel Kant's evaluation of the Ontological Proof. Essentially, Kant argued that the proof failed because it argues in a circle (the conclusion is assumed in the premises). For any predicate to be assigned to any subject, existence must already be assumed. And so, to assign existence as a predicate (which is what one does when they claim existence is part of the essence of something) already assumes the object in question, God, already exists. Obviously, we cannot demonstrate God's existence by already assuming he exists, and Descartes does this unwittingly when assigns existence to the essence of God and argues that from this he proves God's existence. This arguing in a circle though is not the so-called Cartesian Circle.

Another attack made on the argument here for God's existence asks why Descartes needs it? If Descartes clearly and distinctly perceives God's existence in the third Meditation, there should be no need for any further proof or demonstration.

Cartesian Circle

The accusation known as the "Cartesian Circle," is directed towards the latter part of the fifth Meditation where Descartes claims all knowledge and existence is contingent upon God. Essentially, if all of our knowledge is contingent on God, then our knowledge of God's existence must be contingent on God too. In other words, we must assume God exists in order to know God exists clearly and distinctly.

Descartes responds to this critique by distinguishing between the order of knowing, the order of discovery and the order of existence. In the order of existence, it is true that everything is contingent upon God's existence, and hence any knowledge of anything must ultimately come back to this. It is thus also true, that in the order of knowing all things logically depend upon God. But, in the order of discovery (the order in which the Meditations have proceeded), I do not know about the order of knowing or existence prior to discovering God, I simply know that "I" exist as a "thinking thing." Because of this, i never go beyond what I clearly and distinctly perceive at each moment, and thus never assume anything in my premises that I argue for in my conclusions. But, once I have discovered this truth, Descartes argues that it is only by remembering this that I can have certain knowledge of anything else.

Meditation Six: Concerning the Existence of Material Things, and the Real Distinction between Mind and Body

The sixth Meditation is one of the most highly contested Meditations as it is within that Descartes explores the relation between mind and body and what is traditionally interpreted as a mind-body dualism. Before exploring the mind-body relation though, Descartes meditates on the more general mind-world interaction.

Descartes recalls that we now know, "I" exist as a "thinking thing," that "I" am different than "extended things," that God exists and is no deceiver, that I can avoid error, and that ideas that present themselves as clear and distinct can be known as independent, individual things. Given these, especially given that God is no deceiver and has created my nature, I notice that I cannot help but think the book I'm reading is a real, corporeal, independent object. That if I were to set the book down, leave the room, and come back, the book would have remained where I left it the whole time. Yes, I can account for a book simply using my imagination, but my understanding tells me that the book is real, and it is my nature to think this way. But, if God is not a deceiver and did not create my nature fallibly, then my nature cannot be wrong, the book must exist independently of my thinking self. And so, Descartes has gained back everything he has lost, including his sense perceptions. Apple by apple, he has refilled the bushel without allowing any rotten ones back in. As Descartes notes though, there is one unique body in this external world which my nature claims uniquely, apart from all other objects, that is my body. But, if my body is an extended thing and my mind a thinking thing, how do they interact?

It is here that Descartes has been the focus of much scrutiny. Descartes describes the mind and body as two independent substances (res cogitons and res extensa respectively) who interact through the pineal gland. Though this paints a crude picture, often described as the mind controlling the body through a remote control, Descartes is a little more careful than this. He describes the relationship as closer than a captain to his ship, for when the ship breaks the captain does not feel physical pain, but when the body breaks, the mind does feel pain. The problem still remains though of how two substances, which technically must be completely independent and occupy separate "realms," could possibly interact? If they are so metaphysically distinct interaction should be impossible.

A more sympathetic interpretation of Descartes relies on his definition of substance in the Principles of Philosophy and an understanding of reality as scalar. In the Principles Descartes writes, “By substance I can only mean one thing, God, for by substance I mean something which can exist in such a way that it depends on no other for its existence." In other words, when referencing res cogitons or res extensa as substances, Descartes can only mean this in some derived sense. Given this, they need not be understood as substances which depend on no other for existence. Along with this, Descartes believes res cogitons has more objective reality than res extensa and because of this, res cogitons could cause certain effects in res extensa. The only problem with this interpretation is that it makes difficult the reverse situation, how can we explain res extensa having an effect on res cogitons if it has less objective reality, the principal of sufficient causality prevents this. There are ways around this, but they require more than the text immediately allows. Either way, the more sympathetic interpretation tends to grant Descartes the possibility of res cogitons and res extensa interacting.

Conclusion

The path the Meditations takes begins in methodological, or hyperbolic doubt and ends in certitude. Having doubted everything, even his own existence, Descartes rebuilds the foundations of knowledge. He progresses from knowing "I" exist, to God exists, to everything clearly and distinctly perceived as existing independently existing. In other words, he has provided the ground for the natural sciences as they are now metaphysically rooted in God and epistemically known through infallible clear and distinct perceptions linked through perfect logical deduction.

Mathematical legacy

Rene Descartes said "Nature can be divined through numbers."

Mathematicians consider Descartes of the utmost importance for his discovery of analytic geometry. Up to Descartes's times, geometry, dealing with lines and shapes, and algebra, dealing with numbers, appeared as completely different subsets of mathematics. Descartes showed how to translate many problems in geometry into problems in algebra, by using a coordinate system to describe the problem.

Descartes's theory provided the basis for the calculus of Newton and Leibniz, by applying infinitesimal calculus to the tangent problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics [1]. This appears even more astounding when one keeps in mind that the work was just intended as an example to his Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la verité dans les sciences (Discourse on the Method to Rightly Conduct the Reason and Search for the Truth in Sciences, known better under the shortened title Discours de la méthode).

Descartes also made contributions in the field of Optics, for instance, he showed by geometrical construction using the Law of Refraction that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42° (i.e. the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow's centre is 42°). [2]

Writings by Descartes

- Discourse on Method (1637): an introduction to "Dioptrique', on the "Météores' and 'La Géométrie'; a work for the grand public, written in French.

- La Géométrie (1637)

- Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), also known as 'Metaphysic meditations', with a series of six objections. This work was written in Latin, language of the learned.

- Les Principes de la philosophie (1644), work rather destined for the students.

- The Singing Epitaph (1646).

Trivia

It is claimed that during the 1640s Descartes travelled with an artificial female companion called Francine, named after his daughter. This may be a myth linked with his statements about the nature of the mind, or an early automaton, or Gynoid.

Descartes was ranked #49 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ^ Jan Gullberg (1997). Mathematics From The Birth Of Numbers. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04002-X.

- ^ P A Tipler, G Mosca (2004). Physics For Scientists And Engineers Extended Version. W H Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4389-2.

See also

- Dualistic interactionism

- Baruch Spinoza

- Asteroid 3587 Descartes, named after the philosopher

- Defect (geometry)

- Analytic geometry

- Cartesian coordinate system

External links

- A summary of his book "A Discourse On Method"

- (French) French Audio Book (mp3) : excerpt about animals/machines from Discourse On the Method

- Discourse On the Method – at Project Gutenberg

- Selections from the Principles of Philosophy – at Project Gutenberg

- Detailed biography of Descartes

- CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Rene Descartes

- READABLE versions of Descartes's Meditations and Discourse on the Method.

- Conscientia in Descartes

- descartes, an open source function plotter named after the inventor of Cartesian coordinates

- Biography, Bibliography, Analysis (in French)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy (ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.