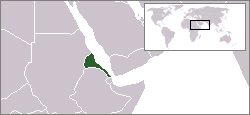

Eritrea

| Hagere Ertra State of Eritrea | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Ertra, Ertra, Ertra | |||||

| Capital | Asmara 15°20′N 38°55′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | none at national level1 | ||||

| Government | Transitional government | ||||

| - President | Isaias Afewerki | ||||

| Independence | from Ethiopia | ||||

| - de facto | May 24 1991 | ||||

| - de jure | May 24 1993 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 117,600 km² (100th) 45,405 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - July 2005 estimate | 4,401,000 | ||||

| - 2002 census | 4,298,269 | ||||

| - Density | 37/km² 96/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $4.471 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $1,000 | ||||

| HDI (2005) | |||||

| Currency | Nakfa (ERN)

| ||||

| Time zone | EAT (UTC+3) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .er | ||||

| Calling code | +291 | ||||

Eritrea is a country situated in northern East Africa. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast. The east and northeast of the country have an extensive coastline on the Red Sea, directly across from Saudi Arabia and Yemen. The Dahlak Archipelago and several of the Hanish Islands are part of Eritrea.

Eritrea was consolidated into a colony by the Italian government on January 1, 1890.[1] Upon Italy's losses in World War II, Eritrea was ruled as a British protectorate between 1941 and 1952.[2] Following a UN plebiscite in 1950, a resolution 390 (V)[3] was adopted to have Eritrea enter into a federation with Ethiopia in 1952. Emperor Haile Selassie I, nevertheless annexed Eritrea as Ethiopia's 14th province in 1961 sparking the 30-year war that lasted from 1961 to 1991. Following a UN supervised referendum called UNOVER Eritrea declared- and gained international recognition for its independence in 1993.[4]. Eritrea's constitution, adopted in 1997, stipulates that the state is a presidential republic with a unicameral parliamentary democracy. The constitution, however, has not yet been implemented fully due to, according to the government, the prevailing border conflict with Ethiopia which began in May 1998.

Eritrea is a multilingual and multicultural country with two dominant religions (Sunni Islam and Oriental Orthodox Christianity) and nine ethnic groups. The country has no official language, but it has three working languages: Tigrinya, Arabic and English. Italian is also widely spoken amongst the older generations. [5]

History

The oldest written reference to the territory now known as Eritrea is the chronicled expedition launched to the fabled Punt (or "Ta Netjeru," meaning land of the Gods) by the Ancient Egyptians in the twenty-fifth century BC under Pharaoh Sahure[6]. Later sources from the Pharaoh Hatshepsut in the 15th century BC present a more detailed portrayal of an expedition in search of incense. The geographical location of the missions to Punt is described as roughly corresponding to the southern west coast of the Red Sea.

The modern name Eritrea was first employed by the Italian colonialists in the late nineteenth century. It is the Italian form of the Greek name Ερυθραία (Erythraîa), which derives from the Greek term for the Red Sea.

Pre-history

One of the oldest hominids representing a link between Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens, was found in Buya (Eritrean Danakil) in 1995 by Italian scientists. The cranium was dated to over 1 million years old.[7] Furthermore, the Eritrean Research Project Team, composed of Eritrean, Canadian, American, Dutch, and French scientists, discovered in 1999 some of the first examples of humans using tools to harvest marine resources at a site near the bay of Zula south of Massawa along the Red Sea coast. The site contained obsidian tools dated to over 125,000 years old, from the paleolithic era.[8] Epipaleolithic or mesolithic remains in the form of cave paintings in central and northern Eritrea attest to the early settlement of hunter-gatherers in this region.

A US paleontologist, William Sanders of the University of Michigan also discovered the missing link between ancient and modern elephants in the form of the fossilized remains of a pig-sized creature in Eritrea. Sanders claims that the dating of the fossil to 27 million years ago also pushes the origins of elephants and mastodons five million years further into the past than previously recorded and asserts that modern elephants originated in Africa, in contrast to mammals such as rhinos that had their origins in Europe and Asia and migrated into Africa. In addition to Sanders, the research team included scientists from the Elephant Research Foundation of Wayne State University in Michigan, USA, University of Asmara in Eritrea; Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, PA, USA; the Eritrean ministry of mines and energy; Global Resources in Asmara, Eritrea; the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris; the National Museum of Eritrea; and German Primate Center in Gottingen, Germany.

Early history

The earliest evidence of agriculture, urban settlement and trade in Eritrea was found in the region inhabited by people dating back to 3500 B.C.E. in the archaeological sites called the Gash group. Based on the archaeological evidence, there seems to have been a connection between the peoples of the Gash group and the civilizations of the Nile Valley namely Ancient Egypt and Nubia.[9]. Ancient Egyptian sources also give references to cities and trading posts along the southwestern Red Sea coast, roughly corresponding to modern day Eritrea, calling this the land of Punt famed for its incense. Expeditions to this very land were launched by the Ancient Egyptians as early as the 25th century B.C.E. and were chronicled in more detail in later expeditions during the reign of the female Pharao Hatshepsut in the 15th century B.C.E.

In the highlands, in one of the capital city Asmara's suburbs Sembel at the mouth of the river Anseba, another site was found from the ninth century BC of another agricultural and urban settlement that traded both with the Sabaeans across the Red Sea and with the civilizations of the Nile Valley further west along caravan routes that followed the Anseba River. Around this time, several cities with a high amount of Sabean remains (inscriptions, artifacts, monuments, architecture, etc.) seem to emerge in the central highlands and along the central coast including one called Saba. Some are undoubtedly built on top of older sites.

.

Around the eighth century BC, a kingdom known as D'mt was established in what is today northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, with its capital at Yeha in northern Ethiopia and which had extensive relations with the Sabeans in present day Yemen across the Red Sea.[10][11][12] After D'mt's decline around the fifth century BC, the state of Aksum arose in the northern Ethiopian Highlands. It grew during the fourth century BC and came into prominence during the first century AD, minting its own coins by the third century, converting in the fourth century to Christianity, as the second official Christian state (after Armenia) and the first country to feature the cross on its coins. According to Mani, it grew to be one of the four greatest civilizations in the world, on a par with China, Persia, and Rome. In the 7th century AD; with the advent of Islam across the Red Sea in Arabia, Aksum's trade and power on the Red Sea began to decline and the center moved farther inland to the highlands of what is today Ethiopia.

Medieval history

During the medieval period, contemporary with and following the disintegration of the Axumite state, several states as well as tribal and clan lands emerged in the area known today as Eritrea. Between the eighth and thirteenth century, northern and western Eritrea had largely come under the domination of the Beja, an Islamic, Cushitic people from northeastern Sudan. They formed five independent kingdoms known as: Naqis, Baqlin, Bazin, Jarin and Qata.[13] The Beja brought Islam to large parts of Eritrea and connected the region to the greater Islamic world dominated by the Ummayad Caliphate, followed by the Abbasid (and Mamluk) and later the Ottoman Empire. The Ummayads had taken the Dahlak archipelago by 702. In the main highland area and adjacent coastline of what is now Eritrea there emerged a Kingdom called Midir Bahr or Midri Bahri (Tigrinya) ruled by the Bahr negus (or Bahr negash, "ruler of the sea"), [14] Parts of the southwestern lowlands were under the dominion of the Funj sultanate of Sinnar. Eastern areas under the control of the Afar since ancient times came to form part of the sultanate of Adal and when that disintegrated, the coastal areas, there among those pertaining today to Eritrea, had become ottoman vassals. As the kingdom of Midre Bahri and feodal rule was weakened, the main highland (Kebessa) areas in Eritrea would later be named Mereb Mellash, meaning "beyond the Mereb," defining the region as the area north of the Mareb River which to this day is a natural boundary between the modern states of Eritrea and Ethiopia. [15] Roughly the same area also came to be referred as Hamasien in the 19th century, before the invasion of Ethiopian King Yohannes IV which immediately preceded and was partly repulsed by Italian colonialists. In these areas, feodal authority was particularly weak or inexistent and the autonomy of the landowning peasantry was particularly strong, a kind of Republic was exemplified by the a set of local customary laws legislated by elected elders councils (shimagile)[16]

An Ottoman invading force under Suleiman I conquered Massawa in 1557, building what is now considered the 'old town' of Massawa on Batsi island. They also conquered the towns of Hergigo, and Debarwa, the capital city of the contemporary Bahr negus (ruler), Yeshaq. Suleiman's forces fought as far south as southeastern Tigray in Ethiopia before being repulsed. Yeshaq was able to retake much of what the Ottomans captured with Ethiopian assistance, but he later twice revolted against the Emperor of Ethiopia with Ottoman support. By 1578, all revolts had ended, leaving the Ottomans in control of the important ports of Massawa and Hergigo and their environs, and leaving the province of Habesh to Beja Na'ibs (deputies). The Ottomans maintained their dominion over the northern coastal areas for nearly 300 years. Their possessions were left to their Egyptian heirs in 1865 and were taken over by the Italians in 1885.

Colonial era

A Roman Catholic priest by the name of Giuseppe Sapetto acting on behalf of a Genovese shipping company called Rubattino in 1869 purchased the locality of Assab from the local sultan. This happened in the same year as the opening of the Suez Canal.[17]

In the ongoing Scramble for Africa, Italy as one of the European colonial powers began vying for a possession along the strategic coast of what was to become the world's busiest shipping lane. With the approval of the Italian parliament and King Umberto I of Italy (later succeeded by his son Victor Emmanuel III), the government of Italy bought the Rubattino company's holdings and expanded its possessions northward along the Red Sea coast toward and beyond Massawa, encroaching on and quickly expelling previously 'Egyptian' possessions. The Italians met with stiffer resistance in the Eritrean highlands from the army of the Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes IV. Nevertheless the Italians consolidated their possessions into one colony, henceforth known as Eritrea, territory of Italy as of New Years Day 1890. The Italians remained the colonial power in Eritrea throughout the lifetime of fascism and the beginnings of World War II when they were defeated by Allied forces in 1941, and Eritrea became a British protectorate. [18]

After the war, the United Nations conducted a lengthy inquiry regarding the status of Eritrea, with the superpowers each vying for a stake in the state's future. Britain the last administrator at the time put forth the suggestion to partition Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia, separating Christians and Muslims. The idea was instantly rejected by Eritrean political parties as well as the UN.[19]. The United States point of view was expressed by its then chief foreign policy advisor John Foster Dulles who said:

- "From the point of view of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless, the strategic interests of the United States in the Red Sea Basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country [Eritrea] has to be linked with our ally, Ethiopia," — John Foster Dulles, 1952.

A UN plebiscite voted 46 to 10 to have Eritrea be federated with Ethiopia which was later stipulated on December 2 of 1950 in resolution 390 (V). Eritrea would have its own parliament and administration and would be represented in what had been the Ethiopian parliament and was now the federal parliament.[20] In 1961 the 30-year Eritrean Struggle for Independence, began after years of peaceful student protests against Ethiopian violation of Eritrean democratic rights and autonomy had culminated in violent repression and the Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie I's dissolution of the federation in 1961 followed by shutting down the parliament and declaring Eritrea the 14th province of Ethiopia in 1962.[21].

Struggle for independence

Eritreans formed the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) and rebelled. The ELF was initially a conservative grass-roots movement dominated by Muslim lowlanders and thus received backing from Arab socialist governments such as Syria and Egypt. Ethiopia's imperial government received support from the United States which had established a radio listening base (the Kagnew base) in Eritrea's Ethiopian-occupied capital, Asmara. Internal divisions within the ELF based on religion, ethnicity, clan and, sometimes, personalities and ideologies, led to the weakening and factioning of the ELF from which sprung the Eritrean People's Liberation Front. The EPLF professed Marxism and egalitarian values devoid of gender, religion, or ethnic bias. It came to be supported by a growing Eritrean diaspora. Bitter fighting broke out between the ELF and EPLF during the late 1970s and 1980s for dominance over Eritrea. The ELF continued to dominate the Eritrean landscape well into the 1970s when the struggle for independence neared victory due to Ethiopia's internal turmoil caused by the socialist revolution against the monarchy. The ELF's gains suffered when Ethiopia was overtaken by the Derg, a Marxist military junta with backing from the Soviet Union and other communist countries. Nevertheless, Eritrean resistance continued mainly in the northern parts of the country around the Sudanese border from where the most important supply lines came. The heavily bombarded and embattled northern town of Nakfa came to symbolize the Eritrean struggle. (The Eritrean currency is named after it.)[22]

The numbers of the EPLF swelled in the 1980s as did that of Ethiopian resistance movements with which the EPLF struck alliances to overthrow the communist Ethiopian regime. However, due to their Marxist orientation, neither of the resistance movements fighting Ethiopia's communist regime could count on US or other support against the Soviet backed might of the Ethiopian military, which has been sub-Saharan Africa's largest, outside of South Africa. The EPLF relied largely on armaments captured from the Ethiopian army itself as well as financial and political support from the Eritrean diaspora and the cooperation of neighbouring states hostile to Ethiopia such as Somalia and Sudan (although the support of the latter was briefly interrupted and turned into hostility in agreement with Ethiopia during the Gaafar Nimeiry administration between 1971 and 1985). Drought, famine, and intensive offensives launched by the Ethiopian army on Eritrea took a heavy toll on the population — more than half a million fled to Sudan as refugees. Amid the culmination of Soviet support to Ethiopia and a major fall-out between Eritrean and Ethiopian anti-government rebels, the EPLF achieved two of its greatest and most decisive victories. In 1985, Eritrean elite commandos infiltrated the Ethiopian and Soviet held air force base in Asmara and destroyed all 30 fighter jets there, suffering only one casualty. In 1988 during a massive Ethiopian military offensive against Eritrean rebels, a third of the Ethiopian army was annihilated in the northern Eritrean town of Afabet. [23]

Following the decline of the Soviet Union in 1989 and diminishing support for the Ethiopian war, Eritrean rebels advanced further, capturing the port of Massawa and putting the Ethiopian and Soviet naval capabilities there out of action. By 1990 and early 1991 virtually all Eritrean territory had been liberated by EPLF except for the capital, whose only connection with the rest of government-held Ethiopia during the last year of the war was by an air-bridge. In 1991, Eritrean and Ethiopian rebels jointly held the Ethiopian capital under siege as the Ethiopian communist dictator Mengistu Haile mariam fled to Zimbabwe where he lives to this day despite requests for extradition. The Ethiopian army finally capitulated and Eritrea was completely in Eritrean hands in May 24, 1991 when the rebels marched into Asmara while Ethiopian rebels with Eritrean assistance overtook the government in Ethiopia. The new Ethiopian government conceded to Eritrea's demands to have an internationally (UN) supervised referendum dubbed UNOVER to be held in Eritrea which ended in April 1993 with an overwhelming vote by Eritreans for independence. This was declared on the historical date of May 24, 1993.[24]

Independence

Upon Eritrea's declaration of independence, the leader of the EPLF, Isaias Afewerki, became Eritrea's first Provisional President, and the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (later renamed the People's Front for Democracy and Justice, or PFDJ) created a government.[25]

Faced with limited economic resources and a country shattered by decades of war, the government embarked on a reconstruction and defense effort later called the Warsai Yikalo Program project based on the labor of national servicemen and women. It is still ongoing and combines military service with construction, teaching as well as agricultural work to improve the country's food security.[26]

The government also attempts to tap into the resources of the Eritreans living abroad by levying a 2% tax on the gross income of those who wish to gain full economic rights and access as citizens in Eritrea (land ownership, business license etc).[27] while at the same time encouraging tourism and investment both from Eritreans living and abroad and people of other nations and nationalities.

This has been complicated by Eritrea's tumultuous relations with its neighbors, lack of stability and subsequent political problems.

Eritrea severed diplomatic relations with Sudan in 1994 citing that the latter was hosting Islamic terrorist groups to destabilize Eritrea and both countries entered into an acrimonious relationship, each accusing the other of hosting various opposition rebel groups or "terrorists" and soliciting outside support to destabilize the other. Diplomatic relations were resumed over 10 years later in 2005 following a reconciliation agreement reached with the help of Qatar's negotiation in 1999[28][29]. Eritrea now plays a prominent role in the internal Sudanese peace and reconciliation effort[30].

Eritrea was also embroiled in a brief war with Yemen over a border dispute surrounding the Hanish Islands in 1996 which was later resolved by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 1998 [31] and relations between both states have since normalized.

Perhaps the conflict with the deepest impact on independent Eritrea has been the renewed hostility with Ethiopia. In 1998, a border war with Ethiopia over the town of Badme occurred. The Eritrean-Ethiopian War ended in 2000 with a negotiated agreement known as the Algiers Agreement, which assigned an independent, UN-associated boundary commission known as the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), whose task was to clearly identify the border between the two countries and issue a final and binding ruling. Along with the agreement the UN established a Temporary Security Zone consisting of a 25 km demilitarized buffer zone within Eritrea running along the length of the disputed border between the two states and patrolled by UN troops in the mission named UNMEE. Ethiopia was to withdraw to positions held before the outbreak of hostilities in May of 1998 there among Badme. The peace agreement would be completed with the implementation of the Border Commission's ruling, also ending the task of the peacekeeping mission of UNMEE. The EEBC's verdict came in April 2002 which awarded Badme to Eritrea. However, Ethiopia still refuses to implement the ruling it had signed, resulting in the continuation of the UNMEE mission and a continued hostility between the two states who as of yet do not have any diplomatic relations.[32] Diplomatic relations with Djibouti were briefly severed during the border war with Ethiopia in 1998 but later resumed in 2000 due to a dispute over Djibouti's intimate relation with Ethiopia during the war[33].

Regions and districts

Eritrea is divided into six regions (zobas) and subdivided into districts ("sub-zobas"). The geographical extent of the regions is based on their respective hydrological properties. This a dual intent on the part of the Eritrean government: to provide each administration with sufficient control over its agricultural capacity and eliminate historical intra-regional conflicts.

The regions, followed by the sub-region, are:

| No. | Region (ዞባ) | Sub-region (ንኡስ ዞባ) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Central (ዞባ ማእከል) |

Berikh, Ghala-Nefhi, Semienawi Mibraq, Serejaka, Debubawi Mibraq, Semienawi Mi'erab, Debubawi Mi'erab |

| 2 | Southern (ዞባ ደቡብ) |

Adi Keyh, Adi Quala, Areza, Debarwa, Dekemhare, Mai Ayni, Mai Mne, Mendefera, Segeneiti, Senafe, Tserona |

| 3 | Gash-Barka (ዞባ ጋሽ ባርካ) |

Agordat, Barentu, Dghe, Forto, Gogne, Haykota, Logo-Anseba, Mensura, Mogolo, Molki, Guluj, Shambuko, Tesseney, La'elay Gash |

| 4 | Anseba (ዞባ ዓንሰባ) |

Adi Tekelezan, Asmat, Elabered, Geleb, Hagaz, Halhal, Habero, Keren City, Kerkebet, Sel'a |

| 5 | Northern Red Sea (ዞባ ሰሜናዊ ቀይሕ ባሕሪ) |

Afabet, Dahlak, Ghel'alo, Foro, Ghinda, Karura, Massawa, Nakfa, She'eb |

| 6 | Southern Red Sea (ዞባ ደቡባዊ ቀይሕ ባሕሪ) |

Are'eta, Central Dankalia, Southern Dankalia, Assab |

Politics and government

The National Assembly of 150 seats (of which 75 were occupied by handpicked EPLF guerilla members while the rest went to local candidates and diasporans more or less sympathetic of the regime), formed in 1993 shortly after independence, "elected" the current president, Isaias Afewerki. No time frame was announced for the alleged obscure presidency. National elections have been periodically scheduled and canceled. Independent local sources of political information on Eritrean domestic politics are scarce; in September 2001 the government closed down all of the nation's privately owned print media, and outspoken critics of the government have been arrested and held without trial, according to various international observers, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. In 2004 the U.S. State Department declared Eritrea a Country of Particular Concern (CPC) for its alleged record of religious persecution (see below).

National elections

Eritrean National elections were set for 1997 and then postponed until 2001; it was then decided that because 20% of Eritrea's land was under occupation that elections would be postponed until the resolution of the conflict with Ethiopia. However, uninspected local elections have continued in Eritrea. The most recent round of local government elections were held in May 2004. On further elections, the President's Chief of Staff, Yemane Ghebremeskel said,[34]

| “ | The electoral commission is handling these elections this time round so that may be the new element in this process. The national assembly has also mandated the electoral commission to set the date for national elections, so whenever the electoral commission sets the date there will be national elections. It's not dependent on regional elections, although that might be a very helpful process.

Multipartyism, in general principle yes, it is there but the law on political parties has to be approved by the national assembly. It was not approved the last time. The view from the beginning was that you don't necessarily need a party law to hold national elections. You can have national elections and the party law can be adopted at any time. So in terms of commitment it's very clear, in terms of the process it has its own pace, its own characteristics. |

” |

Foreign relations

Eritrea is a member in good standing of the African Union (AU), the successor of the Organization of African Unity (OAU). But it has withdrawn its representative to the AU in protest of the AU's lack of leadership in facilitating the implementation of a binding border decision demarcating the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Eritrea's relationship with the United States is complicated. Although the two nations have a close working relationship regarding the on-going war on terror, there has been a growing tension in other areas. Eritrea's relationship with Italy and the EU has become equally strained in many areas in the last three years.

Within the region, Eritrea's relations with Ethiopia turned from that of close alliance to a deadly rivalry that led to a war from May, 1998 to June 2000 in which 19,000 Eritreans were killed.

External issues include an undemarcated border with Sudan, a war with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in 1996, and a recent border conflict with Ethiopia.

The undemarcated border with Sudan poses a problem for Eritrean external relations.[35] After a high-level delegation to Sudan from the Eritrean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ties are being normalized. Meanwhile, Eritrea has been recognized as a broker for peace between the separate factions of the Sudanese civil war. "It is known that Eritrea played a role in bringing about the peace agreement [between the Southern Sudanese and Government],"[36] while the Sudanese Government and Eastern Front rebels have requested Eritrea to mediate peace talks.[37]

A dispute with Yemen over the Hanish Islands in 1996 resulted in a brief war. As part of an agreement to cease hostilities the two nations agreed to refer the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. At the conclusion of the proceedings, both nations acquiesced to the decision. Since 1996 both governments have remained wary of one another but relations are relatively normal.[38]

The undemarcated border with Ethiopia is the primary external issue facing Eritrea. This led to a long and bloody border war between 1998 and 2000. As a result, the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) is occupying a 25 kilometers by 900 kilometers area on the border to help stabilize the region.[39] Disagreements following the war have resulted in stalemate punctuated by periods of elevated tension and renewed threats of war.[40][41][42] Central to the continuation of the stalemate is Ethiopia's failure to abide by the border delimitation ruling and reneging on its commitment to demarcation. The stalemate has led the President of Eritrea to urge the UN to take action on Ethiopia. This request is outlined in the Eleven Letters penned by the President to the United Nations Security Council. The situation is further escalated by the continued effort of the Eritrean and Ethiopian leaders in supporting each other's opposition. On July 26, 2007, the Assicoated Press reported that Eritrea had been supplying weapons for a Somali insurgant group with ties to Al Qaeda called Shabab. The incident has fueled concerns that Somalia may become the grounds for a de-facto war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, who sent forces to Somalia in December 2006 to help stabilize the country and reinforce the internationally-backed government. [43]

Geography

Eritrea is located in East Africa, more specifically the Horn of Africa, and is bordered on the northeast and east by the Red Sea. The country is virtually bisected by one of the world's longest mountain ranges, the Great Rift Valley, with fertile lands to the west and the descent to desert in the East. Off the sandy and arid coastline is situated the Dahlak Archipelago and its fishing grounds. The land to the south, in the highlands, is slightly drier and cooler. Eritrea at the southern end of the Red Sea is the home of the fork in the rift.

The Afar Triangle or Danakil Depression of Eritrea is the probable location of a triple junction where three tectonic plates are pulling away from one another: the Arabian Plate, and the two parts of the African Plate (the Nubian and the Somalian) splitting along the East African Rift Zone (USGS). The highest point of the country, Amba Soira, is located in the centre of Eritrea, at 3 018 metres (9,902 ft) above sea level. In 2006, Eritrea announced it would become the first country in the world to turn its entire coast into an environmentally protected zone. The 1 347 km (837 mile) coastline, along with another 1 946 km (1,209-miles) of coast around its more than 350 islands, will come under governmental protection.

The main cities of the country are the capital city of Asmara and the port town of Asseb in the southeast, as well as the towns of Massawa to the east, and Keren to the north.

Economy

Like the economies of many other African nations, the economy is largely based on subsistence agriculture, with 80% of the population involved in farming and herding. The only natural disaster that sometimes affects Eritrea, drought, has often created trouble in the farming areas. [1]

The Eritrean-Ethiopian War severely hurt Eritrea's economy. GDP growth in 1999 fell to less than 1%, and GDP decreased by 8.2% in 2000. The May 2000 Ethiopian offensive into southern Eritrea caused some $600 million in property damage and loss, including losses of $225 million in livestock and 55,000 homes. The attack prevented planting of crops in Eritrea's most productive region, causing food production to drop by 62%.[44][45]

Even during the war, Eritrea developed its transportation infrastructure, asphalting new roads, improving its ports, and repairing war-damaged roads and bridges as a part of the Warsay Yika'alo Program. The most significant of these projects has been the building of a coastal highway of more than 500 km connecting Massawa with Asseb as well as the rehabilitation of the Eritrean Railway. The rail line now runs between the Port of Massawa and the capital Asmara.

Eritrea's economic future remains mixed. The cessation of Ethiopian trade, which mainly used Eritrean ports before the war, leaves Eritrea with a large economic hole to fill. Eritrea's economic future depends upon its ability to master fundamental social problems like illiteracy, and low skills.

Society

Demographics

Eritrean society is ethnically heterogeneous. Independent census has yet to be conducted but the Tigrinya and the Tigre people together make up about 80%. The rest of the population comprises the smaller populations of the Saho, Nara, Hedareb, Beja, Afar, Bilen, Kunama, and the Rashaida. Each nationality speaks a different native tongue but, typically, many of the minorities speak more than one language. For example, the Jebertis are Muslim Tigrinyas who consider themselves a separate ethnicity, but in Eritrea ethnicity is determined by language so they are not officially recognized as separate from the Tigrinya.

There exist minorities of Italians and Ethiopian Tigrayans. Neither is generally given citizenship unless through marriage or having it conferred upon them by the State.

The most recent addition to the nationalities of Eritrea is the Rashaida. The Rashaida came to Eritrea in the 19th century[46] from the Arabian Coast. The Rashaida do not typically intermarry, are typically nomadic, and number approximately 61,000, less than 1% of the population.

The Kunama are one of the earliest settled peoples in Eritrea. They adopted rain-fed agriculture and settled into communal villages in the 'lowlands' of Eritrea.

Between 900 and 500 BC Eritrea experienced massive migrations and cultural contacts from Saba in southern Arabia. The Sabean area in Eritrea is mainly to be found in the Kebessa highlands surrounding the capital Asmara and extending southwards. There the Sabeans found the same geographical conditions as in their native Saba, suitable to terracing and their pre-existing agricultural modes of production.

Languages

Many languages are spoken in Eritrea today. The two language families that most of the languages stem from are the Semitic and Cushitic families. The Semitic languages in Eritrea are Arabic (spoken natively by the Rashaida Arabs), Tigre, Tigrinya, and the newly recognized Dahlik; these languages (primarily Tigre and Tigrinya) are spoken as a first language by over 80% of the population. The Cushitic languages in Eritrea are just as numerous, including Afar, Beja, Blin, and Saho. Kunama and Nara are also spoken in Eritrea and belong to the Nilo-Saharan language family. English is spoken to a degree by more educated Eritreans, and there are still some speakers of Italian leftover from colonial times.

The local Tigrinya and the wider Arabic language are the two predominant languages for official purposes.

Education

There are five levels of education in Eritrea: pre-primary, primary, middle, secondary, and post-secondary. There are nearly 238,000 students in the primary, middle, and secondary levels of education. There are approximately 824 schools[47] in Eritrea and two universities (University of Asmara and the Institute of Science and Technology) as well as several smaller colleges and technical schools.

One of the most important goals of Eritrea's education policy is to provide basic education in each of Eritrea's mother tongues, as well as to develop a self-motivated and conscientious population to fight poverty and disease. Furthermore it is tooled to produce a society that is equipped with the necessary skills to function with a culture of self-reliance in the modern economy.

The education system in Eritrea is also designed to promote private sector schooling, equal access for all groups (i.e., prevent gender discrimination, ethnic discrimination, and class discrimination, etc.) and promote continuing education, both formally and informally.

Barriers to education in Eritrea include traditional taboos, school fees (for registration and materials), and the opportunity costs of low-income households.[48]

Religion

Eritrea has two dominant religions, Christianity and Islam. Muslims, who make up about 50% of the population predominantly follow Sunni Islam. The Christians (about 50%) consist primarily of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, which is the local Oriental Orthodox church, but small groups of Roman Catholics, Protestants, and other denominations also exist.

Since May 2002, the government of Eritrea has only officially recognized the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, Sunni Islam, Catholicism, and the Evangelical Lutheran church. All other faiths and denominations were required to undergo a registration process that was so stringent as to effectively be prohibitive. Among other things, the government's registration system requires religious groups to submit personal information on their membership to be allowed to worship.[citation needed] The few organisations that have met all of the registration requirements have still not received official recognition.[citation needed]

Other faith groups like Jehovah's Witnesses[49], Bahá'í faith, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and numerous Protestant denominations are not registered and cannot worship freely. They have effectively been banned, and harsh measures have been taken against their adherents. Many have been incarcerated for months or even years. None have been charged officially or given access to judicial process. In its 2006 religious freedom report, the U.S. State Department for the third year in a row named Eritrea a "Country of Particular Concern," designating it one of the worst violators of religious freedom in the world.

There is one last native Jew in Eritrea, formerly from a community of hundreds in Asmara, whose ancestors had crossed from Aden in the late 19th century.[50][51]

Culture

The Eritrean region has traditionally been a nexus for trade throughout the world. Because of this, the influence of diverse cultures can be seen throughout Eritrea. Today, the most obvious influences in the capital, Asmara, are that of Italy. Throughout Asmara, there are small cafes serving beverages common to Italy. In Asmara, there is a clear merging of the Italian colonial influence with the traditional Tigrinya lifestyle. In the villages of Eritrea, these changes never took hold.

In the cities, before the Occupation and during the early years, the import of Bollywood films was commonplace, while Italian and American films were available in the cinemas as well. In the 1980s and since Independence, however, American films have certainly become the most common. Vying for market share are films by local producers, who have slowly come into their own. The global broadcast of Eri-TV has brought cultural images to the large Eritrean population in the Diaspora who frequents the country every summer. Successful domestic films are produced by government and independent studios with revenue from ticket sales typically covering the production costs.

Traditional Eritrean dress is quite varied with the Kunama traditionally dressing in brightly colored clothes while the Tigrinya and Tigre traditionally dress in bright white costumes, resembling traditional Oriental and Indian clothing. The Rashaida women are ornately bejeweled and scarfed.

Popular sports in Eritrea are football and bicycle racing. In recent years Eritrean athletes have seen increasing success in the international arena.

Almost unique on the African continent, the Tour of Eritrea is a bicycle race from the hot desert beaches of Massawa, up the winding mountain highway with its precipitous valleys and cliffs to the capital Asmara. From there, it continues downwards onto the western plains of the Gash-Barka Zone, only to return back to Asmara from the south. This is, by far, the most popular sport in Eritrea, though, as of late long-distance running has garnered its own supporters. The momentum for long-distance running in Eritrea can be seen in the successes of Zersenay Tadesse and Mebrahtom (Meb) Keflezighi, both Olympians.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- ↑ http://www.statoids.com/uer.html

- ↑ http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/5/ares5.htm

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-37675/Eritrea

- ↑ "

PDF. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 July 2006

PDF. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 July 2006

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_of_Punt#Punt.27s_location

- ↑ Abbate, Ernesto; Albianelli, Andrea; Azzaroli, Augusto; Benvenuti, Marco; Tesfamariam, Berhane; Bruni, Piero; Cipriani, Nicola; Clarke, Ronald J.; Ficcarelli, Giovanni; Macchiarelli, Roberto; Napoleone, Giovanni; Papini, Mauro; Rook, Lorenzo; Sagri, Mario; Tecle, Tewelde Medhin; Torre, Danilo; Villa, Igor (4 June 1998). A one-million-year-old Homo cranium from the Danakil (Afar) Depression of Eritrea. Nature 393: 458-460.

- ↑ Out of Africa (1999-09-10). Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Fattovich, Rodolfo. "The development of urbanism in the northern Horn of Africa in ancient and medieval times". Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ↑ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, pp.57.

- ↑ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia: 1270-1527 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp.5-13.

- ↑ Megalommatis, Mohammed K.P. "Yemen's Past and Perspectives are in Africa, not a fictitious 'Arab' world"

- ↑ http://american.edu/ted/ice/eritrea.htm

- ↑ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941 – 2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle (United States of America: Signature Book Printing, 2005), pp. 17-8.

- ↑ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict

- ↑ Dennis J. Duncanson Sir'at 'Adkeme Milga'. A Native Law Code of Eritrea

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-37666/Eritrea

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-37666/Eritrea

- ↑ http://www.iht.com/articles/2000/06/10/edold.t_11.php

- ↑ http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/5/ares5.htm

- ↑ Semere Haile The Origins and Demise of the Ethiopia-Eritrea Federation Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 15, 1987 (1987), pp. 9-17

- ↑ Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- ↑ http://www.kent.ac.uk/politics/research/erwp/ciri.htm

- ↑ http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761576168_2/Eritrea.html

- ↑ http://www.dehai.org/conflict/history/birth_of_a_nation.htm#Referendum_Results

- ↑ http://www.shaebia.org/wwwboard/messages/227.html

- ↑ http://travel.state.gov/travel/cis_pa_tw/cis/cis_1111.html

- ↑ http://www.africa.upenn.edu/Hornet/irin_5399b.html

- ↑ http://www.arabicnews.com/ansub/Daily/Day/051210/2005121017.html

- ↑ http://allafrica.com/stories/200705040041.html

- ↑ http://library2.lawschool.cornell.edu/pca/ER-YEchap1.htm

- ↑ http://www.dehai.org/conflict/home.htm?events.htm

- ↑ http://nationsencyclopedia.com/World-Leaders-2003/Djibouti-FOREIGN-POLICY.html

- ↑ Interview of Mr. Yemane Gebremeskel, Director of the Office of the President of Eritrea. PFDJ (2004-04-01). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Eritrea-Sudan relations plummet. BBC (2004-01-15). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Turabi terms USA "world's ignoramuses," fears Sudan's partition. Sudan Tribune (2005-11-04). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Sudan demands Eritrean mediation with eastern Sudan rebels. Sudan Tribune (2006-04-18). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Flights back on between Yemen and Eritrea. BBC (1998-12-13). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Q&A: Horn's bitter border war. BBC (2005-12-07). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Horn tensions trigger UN warning. BBC (2004-02-04). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Army build-up near Horn frontier. BBC (2005-11-02). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Horn border tense before deadline. BBC (2005-12-23). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ "U.N.: Eritrea giving arms to Somalis tied to al Qaeda". CNN (2007-07-26). Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ↑ Economy - overview. CIA (2006-06-6). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Aid sought for Eritrean recovery. BBC (2001-02-22). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Alders, Anne. the Rashaida. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ (2005) Baseline Study on Livelihood Systems in Eritrea. National Food Information System of Eritrea.

- ↑ Kifle, Temesgen (2002). Educational Gender Gap in Eritrea.

- ↑ Jehovah's Witnesses—Eritrea Country Profile. Office of Public Information of Jehovah's Witnesses (2007-07-01). Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ Asmara's last Jew recalls 'good old days'. BBC (2006-04-30). Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- ↑ Eritrea's last native Jew tends graves, remembers. Y Net News (2006-05-02). Retrieved 2006-09-26.

Further reading

- Ancient Ethiopia, David W. Phillipson (1998)

- Cliffe, Lionel; Connell, Dan; Davidson, Basil (2005), Taking on the Superpowers: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution (1976-1982). Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-188-0

- Cliffe, Lionel & Davidson, Basil (1988), The Long Struggle of Eritrea for Independence and Constructive Peace. Spokesman Press, ISBN 0-85124-463-7

- Connell, Dan (1997), Against All Odds: A Chronicle of the Eritrean Revolution With a New Afterword on the Postwar Transition. Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-046-9

- Connell, Dan (2001), Rethinking Revolution: New Strategies for Democracy & Social Justice : The Experiences of Eritrea, South Africa, Palestine & Nicaragua. Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-145-7

- Connell, Dan (2004), Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners. Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-235-6

- Connell, Dan (2005), Building a New Nation: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution (1983-2002). Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-198-8

- Daniel Kendie (2005), The Five Dimensions Of The Eritrean Conflict 1941 - 2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. Signature Book Printing, ISBN 1-932433-47-3

- Firebrace, James & Holand, Stuart (1985), Never Kneel Down: Drought, Development and Liberation in Eritrea. Red Sea Press, ISBN 0-932415-00-8

- Jordan Gebre-Medhin (1989), Peasants and Nationalism in Eritrea. Red Sea Press, ISBN 0-932415-38-5

- Hill, Justin (2002), 'Ciao Asmara, A classic account of contemporary Africa'. Little, Brown, ISBN 978-0349115269

- Iyob, Ruth (1997), The Eritrean Struggle for Independence : Domination, Resistance, Nationalism, 1941-1993. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-59591-6

- Jacquin-Berdal, Dominique; Plaut, Martin (2004), Unfinished Business: Ethiopia and Eritrea at War. Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-217-8

- Johns, Michael (1992), "Does Democracy Have a Chance," Congressional Record, May 6, 1992

- Keneally, Thomas (1990), "To Asmara" ISBN 0446391719

- Killion, Tom (1998), Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-3437-5

- Wrong, Michela (2005), I Didn't Do It For You: how the world betrayed a small African Nation. Harper Collins, ISBN 0-06-078092-4

- Ogbaselassie, G (2006-01-10). Response to remarks by Mr. David Triesman, Britain's parliamentary under-secretary of state with responsibility for Africa. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- Pateman, Roy (1998), Eritrea: Even the Stones Are Burning. Red Sea Press, ISBN 1-56902-057-4

- Rena, Ravinder (2006-01-12). Student-Centered Education is the Best Way of Learning. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- Eritrea-Ethiopia versus western nations (2005-12-09). Retrieved 2006-06-07.

External links

Government

- Official website of the Ministry of Information of Eritrea

- Official website of the Ministry of Education of Eritrea

Other

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.