Ladakh

| Ladakh Jammu and Kashmir • India | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Area | 45,110 km² (17,417 sq mi) |

| Largest city | Leh |

| Population • Density |

270,126 (2001) • 6 /km² (16 /sq mi)[1] |

| Language(s) | Ladakhi, Urdu |

| Infant mortality rate | 19%[2] (1981) |

| Website: leh.nic.in | |

Coordinates:

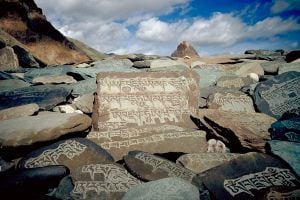

Ladakh (Tibetan script: ལ་དྭགས་; Wylie: la-dwags, Ladakhi IPA: [lad̪ɑks], Hindi: लद्दाख़, Hindi IPA: [ləd̪.d̪ɑːx], Urdu: لدّاخ; "land of high passes") is a province in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir sandwiched between the Kunlun mountain range in the north and the main Great Himalayas to the south. Inhabited by people of Indo-Aryan and Tibetan descent, the region stands as one of the most sparsely populated regions in Kashmir. A remarkable region for many reasons, Ladakh is an area that has its own unique history, culture, and traditions, yet has been caught between the major powers of the area, China, India, Afghanistan, Tibet and, Pakistan.[3]

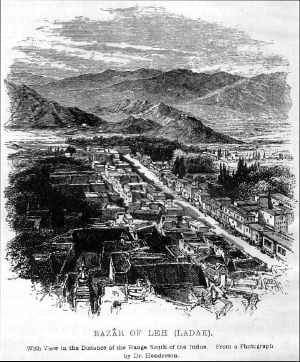

Situated on a high altitude plain, Ladakh became the midway point in the trade route between Punjab, India, and Central Asia. From around 950 C.E., Ladakh had enjoyed independence and prosperity, the kings having descended from Tibetan lineage. The kingdom enjoyed a golden age in the early 1600s when king Singge Namgyal expanded across Spiti and western Tibet. During that era, trade abounded with caravans carrying silk, spices, carpets and narcotics, among other items. Marking the midway spot on the route, Ladakh became a vital meeting place for merchants traveling between Central Asia and India. Thus, it developed a cosmopolitan atmosphere.[4] Ladakh's independence came to an end in 1834 C.E. when Gulab Singh of Jammu conquered it. The British followed, becoming the ruling power in northern India in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Absorbed into the newly created states of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh remained a part of India after the partition in 1947. In 1962, China took control of Ladakh following the Sino-Indian War of 1962.[5]

The people of Ladakh became adherents of Buddhism in the fourth and third century B.C.E. when monks traveled to Tibet to plant Buddhism there. Buddhism's stamp is profound and clearly evident. Every village and town has a temple or monastery whether small or large.[6] In the eighth century Islam made strong inroads to the region. Similar to other areas of India bordering Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan, Ladakh has never parted from Buddhism. Shamanism is also widely practiced, usually incorporated into Buddhism. The practice of fortune-telling is wide spread, especially among the monks of Matho Gompa.[7]

Background

Ladakh has become renowned for its remote mountain beauty and Buddhist culture. Sometimes called "Little Tibet" in light of the strong influence by Tibetan culture. Ladakh gained importance from its strategic location at the crossroads of important trade routes,[8] but since the Chinese authorities closed the borders with Tibet and Central Asia in the 1960, international trade has dwindled. Since 1974, the Indian Government has encouraged tourism in Ladakh.

Leh stands as the largest town in Ladakh. Tibetan Buddhists comprise a majority of Ladakhis, the Shia Muslims having the next largest share of the population.[9] Recently Ladakhis have called for Ladakh to become a union territory because of its religious and cultural differences with predominantly Muslim Kashmir.[10]

History

Rock carvings have been found in many parts of Ladakh, showing that the area has been inhabited from the Neolithic times.[11] Ladakh's earliest inhabitants consisted of a mixed Indo-Aryan population of Mons and Dards, who find mention in the works of Herodotus, Nearchus, Megasthenes, Pliny, Ptolemy, and the geographical lists of the Puranas.[12]

Around the first century, Ladakh formed a part of the Kushana empire. Buddhism came to western Ladakh by way of Kashmir in the second century when much of eastern Ladakh and western Tibet still practiced the Bon religion. The seventh century Buddhist traveler Xuanzang also describes the region in his accounts.

In the eighth century, Ladakh participated in the clash between Tibetan expansion pressing from the East and Chinese influence exerted from Central Asia through the passes, and suzerainty over Ladakh frequently changed hands between China and Tibet. In 842 C.E. Nyima-Gon, a Tibetan royal representative annexed Ladakh for himself after the break-up of the Tibetan empire, and founded a separate Ladakh dynasty. During that period Ladakh underwent Tibetanization resulting in a predominantly Tibetan population. The dynasty spearheaded the "Second Spreading of Buddhism" importing religious ideas from north-west India, particularly from Kashmir.

Faced with the Islamic conquest of South Asia in the thirteenth century, Ladakh choose to seek and accept guidance in religious matters from Tibet. For nearly two centuries, until about 1600, Ladakh experienced raids and invasions from neighboring Muslim states, which led to weakening and fracturing of Ladakh, and partial conversion of Ladakhis to Islam.[9][12]

King Bhagan reunited and strengthened Ladakh and founded the Namgyal dynasty which continues to survive. The Namgyals repelled most Central Asian raiders and temporarily extended the kingdom as far as Nepal,[11] in the face of concerted attempts to convert the region to Islam and destroy Buddhist artifacts.[11] In the early seventeenth century, the Namgyals made efforts to restore destroyed artifacts and gompas, and the kingdom expanded into Zanskar and Spiti. Ladakh fell to the Mughals, who had already annexed Kashmir and Baltistan, but retained their independence.

In the late seventeenth century, Ladakh sided with Bhutan in its dispute with Tibet, which resulted in an invasion by Tibet. Kashmiri help restored Ladakhi rule on the condition of that a mosque be built in Leh and that the Ladakhi king convert to Islam. The Treaty of Temisgam in 1684 settled the dispute between Tibet and Ladakh, but at the cost of severely restricting its independence. In 1834, the Dogras under Zorawar Singh, a general of Ranjit Singh, invaded and annexed Ladakh. They crushed a Ladakhi rebellion in 1842, incorporating Ladakh into the Dogra state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Namgyal family received the jagir of Stok, which it nominally still retains. From the 1850s, European influence increased in Ladakh — geologists, sportsmen and tourists began exploring Ladakh. In 1885, Leh became the headquarters of a mission of the Moravian Church.

At the time of the partition of India in 1947, the Dogra ruler Maharaja Hari Singh pondered whether to accede to the Indian Union or to Pakistan. In 1948, Pakistani raiders invaded the region and occupied Kargil and Zanskar, reaching within 30 km (19 miles) of Leh.[11] The Indian government sent troops into the princely state after the ruler signed the Instrument of Accession making the state a part of the Union of India.

In 1949, China closed the border between Nubra and Xinjiang, blocking old trade routes. The Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 led to a large influx of Tibetan refugees to the region. In 1962 China invaded and occupied Aksai Chin, and promptly built roads connecting Xinjiang and Tibet through it. It also built the Karakoram highway jointly with Pakistan. India built the Srinagar-Leh highway during that period, cutting the journey time between Srinagar to Leh from sixteen days to two.[11] The entire state of Jammu and Kashmir continues in territorial dispute between India on the one hand and Pakistan and China on the other. Kargil had been the scene of fighting in the wars of 1947, 1965, 1971 and the focal point of a potential nuclear conflict during the Kargil War in 1999. The region bifurcated into Kargil and Leh districts in 1979. In 1989, violent riots between Buddhists and Muslims erupted. Following demands for autonomy from the Kashmiri dominated state government, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council founded in 1993.

Geography

Ladakh constitutes India’s highest plateau at over 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[9] It spans the Himalayan and Karakoram mountain ranges and the upper Indus River valley. Historical Ladakh includes the fairly populous main Indus valley, the more remote Zangskar (in the south) and Nubra valleys (to the north over Khardung La), the almost deserted Aksai Chin, and Kargil and Suru Valley areas to the west (Kargil being the second most important town in Ladakh). Before partition, Baltistan (now under Pakistani administration) had been a district in Ladakh. Skardu served as the winter capital of Ladakh while Leh acted as the summer capital.

The mountain ranges in the region formed over a period of forty five million years by the folding of the Indian plate into the more stationary Eurasian Plate. The drift continues, causing frequent earthquakes in the Himalayan region. The peaks in the Ladakh range stand at a medium altitude close to the Zoji-la (5,000–5,500 m or 16,000–18,050 ft), and increase towards south-east, reaching a climax in the twin summits of Nun-Kun (7000 m or 23,000 ft).

The Suru and Zangskar valleys form a great trough enclosed by the Himalayas and the Zanskar range. Rangdum represents the highest inhabited region in the Suru valley, after which the valley rises to 4,400 m (14,436 ft) at Pensi-la, the gateway to Zanskar. Kargil, the only town in the Suru valley, had been an important staging post on the routes of the trade caravans before 1947, being more or less equidistant, at about 230 kilometers from Srinagar, Leh, Skardu, and Padum. The Zangskar valley lies in the troughs of the Stod and the Lungnak rivers. The region experiences heavy snowfall; the Pensi-la stays open only between June and mid-October. The Indus river constitutes the backbone of Ladakh. All major historical and current towns — Shey, Leh, Basgo, and Tingmosgang, situate close to the river.

Ladakh, a high altitude desert as the Himalayas create a rain shadow, denies entry to monsoon clouds. The winter snowfall on the mountains constitutes the main source of water. Recent flooding of the Indus river in the region has been attributed either to abnormal rain patterns, or the retreating of glaciers, both of which might be linked to global warming.[13] The Leh Nutrition Project, headed by Chewang Norphel, also known as the 'Glacier Man', currently creates artificial glaciers as one solution for that problem.[14]

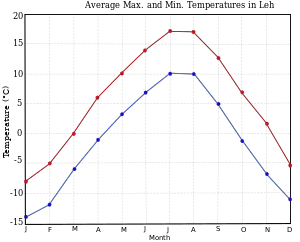

The regions on the north flank of the Himalayas — Dras, the Suru valley and Zanskar — experience heavy snowfall and remain virtually cut off from the rest of the country for several months in the year. Short Summers still prove long enough to grow crops in the lower reaches of the Suru valley. The summer weather, dry and pleasant, has average temperatures between 10–20 °C (50–70 °F), while in winter, the temperature may dip to −15 °C (5 °F). Lack of vegetation makes for a proportion of oxygen less than in many other places at comparable altitudes. Little moisture heightens the effects of rarefied air. Ladakh lies in the Very High Damage Risk cyclone zone.

Flora and fauna

Ferdinand Stoliczka, an Austrian/Czech palaeontologist, who carried out a massive expedition in the region in the 1870s, first studied the wildlife of the region. Vegetation grows along stream beds and wetlands, on high slopes, and in irrigated places while extremely sparse elsewhere.[15]

The fauna of Ladakh have much in common with that of Central Asia in general and that of the Tibetan Plateau in particular. The birds constitute an exception as many migrate from the warmer parts of India to spend the summer in Ladakh. For such an arid area, Ladakh has a great diversity of birds — a total of 225 species have been recorded. Many species of finches, robins, redstarts (like the Black Redstart) and the Hoopoe live in Ladakh during the summer. The Brown-headed Gull normally appear in summer on the river Indus and on some lakes of the Changthang. Resident water-birds include the Brahminy duck, also known as the Ruddy Sheldrake, and the Bar-headed Goose. The Black-necked Crane, a rare species found scattered in the Tibetan plateau, lives in parts of Ladakh. Other birds include the Raven, Red-billed Chough, Tibetan Snowcock and Chukar. The Lammergeier and the Golden Eagle commonly appear.

The Bharal or "blue sheep," common in the Himalayas, ranges from Ladakh to as far as Sikkim. The Ibex, found in high craggy terrain of Europe, North Africa, and Asia, numbers several thousand in Ladakh. The Tibetan Urial sheep, a rare goat that numbers about a thousand, lives at lower elevations, mostly in river valleys, competing with domestic animals. The Argali sheep, a relative of the Marco Polo sheep of the Pamirs with huge horizontal curving horns, number only a couple hundred in Ladakh. The endangered Tibetan Antelope, (Indian English chiru, Ladakhi tsos) has traditionally been hunted for its wool, shahtoosh, valued for its light weight and warmth and as a status symbol. The extremely rare Tibetan Gazelle has habitat near the Tibetan border in southeastern Ladakh. The Kyang, or Tibetan Wild Ass, common in the grasslands of Changthang, numbers about 1,500. Approximately 200 Snow Leopards live in Ladakh, especially in Hemis High Altitude National Park. Other cats in Ladakh even rarer than the snow leopard, include the Lynx, numbering only a few, and the Pallas's cat, which looks somewhat like a house cat. The Tibetan Wolf, which sometimes preys on the livestock of the Ladakhis, has been targeted by area farmers, reducing them to just about 300. A few brown bears live in the Suru valley and the area around Dras. The Tibetan Sand Fox has recently been discovered in the region. Among smaller animals, marmots, hares, and several types of pika and vole nave been commonly sighted.

Government and politics

Ladakh comprises two districts of Jammu and Kashmir: Leh and Kargil, each governed by a Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council based on the pattern of the Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council. Created as a compromise to the demands of Ladakhi people to make Leh district a union territory, the government attempted to reconcile religious and cultural differences with Kashmir. In October 1993, the Indian government and the State government agreed to grant each district of Ladakh the status of Autonomous Hill Council.

Although on the whole there has been religious harmony in Ladakh, religion has tended to get politicized in the last few decades. As early as 1931, Kashmiri neo-Buddhists founded the Kashmir Raj Bodhi Mahasabha that led to some sense of separateness from the Muslims. The bifurcation of the region into Muslim majority Kargil district and Buddhist majority Leh district in 1979 again brought the communal question into fore. The Buddhists in Ladakh accused the overwhelmingly Muslim state government of continued apathy, corruption and a bias in favor of Muslims. On those grounds, they demanded union territory status for Ladakh. In 1989, violent riots erupted between Buddhists and Muslims, provoking the Ladakh Buddhist Association to call for a social and economic boycott of Muslims which went on for three years before being lifted in 1992. The Ladakh Union Territory Front (LUTF), which controls the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council - Leh, demands union territory status for Ladakh.

Economy

For centuries, Ladakh enjoyed a stable and self-reliant agricultural economy based on growing barley, wheat and peas, and keeping livestock, especially yak, dzos (yak-cow cross breed), cows, sheep and goats. At altitudes of 3000 to 4300 m (10,000 and 14,000 ft), the growing season extends only a few months every year, similar to the northern countries of the world. With a scarcity of animals and water supply, the Ladakhis developed a small-scale farming system adapted to their unique environment. A system of channels which funnel water from the ice and snow of the mountains irrigates the land. Barley and wheat constitute the principal crops while rice, previously a luxury in the Ladakhi diet, has become an inexpensive staple through government subsidization.[16]

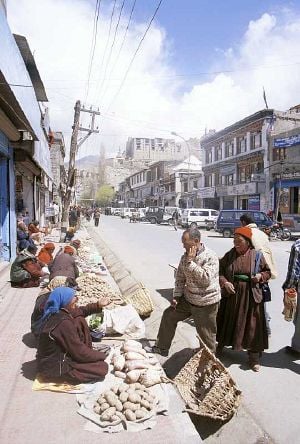

At lower elevations farmers grow fruit while nomadic herders dominate the high altitude Rupshu region. In the past, the locals traded surplus produce for tea, sugar, salt and other items. Apricots and pashmina stand as two items for export. Currently, vegetables, sold in large amounts to the Indian army as well as in the local market, constitute the largest commercially sold agricultural product. Production remains mainly in the hands of small-landowners who work their own land, often with the help of migrant laborers from Nepal. Naked barley (Ladakhi: nas, Urdu: grim) has been a traditional staple crop throughout Ladakh. Growing times vary considerably with altitude. The extreme limit of cultivation exists at Korzok, on the Tso-moriri lake, at 4,600 m (15,100 ft), widely considered the highest fields in the world.[9]

Until recently, Ladakh's geographical position at the crossroads of some of the most important trade routes in Asia had been exploited to the full. Ladakhis collected tax on goods that crossed their kingdom from Turkistan, Tibet, Punjab, Kashmir and Baltistan. A minority of Ladakhi people also worked as merchants and caravan traders, facilitating trade in textiles, carpets, dyestuffs and narcotics between Punjab and Xinjiang. Since the Chinese Government closed the borders with Tibet and Central Asia, that international trade has completely dried up.[11][17]

Since 1974, the Indian Government has encouraged a shift in trekking and other tourist activities from the troubled Kashmir region to the relatively unaffected areas of Ladakh. Although tourism employs only 4 percent of Ladakh's working population, it now accounts for 50 percent of the region's GNP.[11] Extensive government employment and large-scale infrastructure projects — including, crucially, road links — have helped consolidate the new economy and create an urban alternative to farming. Subsidized food, government jobs, tourism industry, and new infrastructure have accelerated a mass migration from the farms into Leh.

Adventure tourism in Ladakh started in the nineteenth century. By the turn of the twentieth century, British officials commonly undertook the 14-day trek from Srinagar to Leh as part of their annual leave. Agencies had been set up in Srinagar and Shimla specializing in sports-related activities — hunting, fishing and trekking. Arthur Neves. The Tourist's Guide to Kashmir, Ladakh and Skardo. (1911), recorded that era.[17] Currently, about 30,000 tourists visit Ladakh every year. Among the popular places of tourist interest include Leh, Drass valley, Suru valley, Kargil, Zanskar, Zangla, Rangdum, Padum, Phugthal, Sani, Stongdey, Shyok Valley, Sankoo, Salt Valley and several popular trek routes like Manali to Ladakh, the Nubra valley, the Indus valley etc.[18]

Transport

Ladakh served as the connection point between Central Asia and South Asia on the Silk Road. Traders frequently undertook The sixty-day journey on the Ladakh route connecting Amritsar and Yarkand through eleven passes until the late nineteenth century.[8] The Kalimpong route between Leh and Lhasa via Gartok, the administrative center of western Tibet constituted another common route in regular. Gartok could be reached either straight up the Indus in winter, or through either the Taglang la or the Chang la. Beyond Gartok, the Cherko la brought travelers to the Manasarovar and Rakshastal lakes, and then to Barka, which connected to the main Lhasa road. Those traditional routes have been closed since the Ladakh-Tibet border has been sealed by the Chinese government. Other routes connected Ladakh to Hunza and Chitral but similarly, currently no border crossing exists between Ladakh and Pakistan.

Presently, only two land routes from Srinagar and Manali to Ladakh operate. Travelers from Srinagar start their journey from Sonamarg, over the Zoji la pass (3,450 m, 11,320 ft) via Dras and Kargil (2,750 m, 9,022 ft) passing through Namika la (3,700 m, 12,140 ft) and Fatu la (4,100 m, 13,450 ft.) That has been the main traditional gateway to Ladakh since historical times. With the rise of militancy in Kashmir, the main corridor to the area has shifted from the Srinagar-Kargil-Leh route via Zoji la to the high altitude Manali-Leh Highway from Himachal Pradesh. The highway crosses four passes, Rohtang la (3,978 m, 13,050 ft), Baralacha la (4,892 m, 16,050 ft), Lungalacha la (5,059 m, 16,600 ft) and Tanglang la (5,325 m, 17,470 ft), staying open only between July and mid-October when snow has been cleared from the road. One airport serves Leh with multiple daily flights to Delhi on Jet Airways, Air Deccan, and Indian, and weekly flights to Srinagar and Jammu.

Buses run from Leh to the surrounding villages. About 1,800 km (1,100 mi) of roads in cross Ladakh of which 800 km (500 mi) has been surfaced.[19] The Manali-Leh-Srinagar road makes up about half of the road network, the remainder side roads. A complex network of mountain trails which provides the only link to most of the valleys, villages and high pastures criss-crosses Ladakh. For the traveler with a number of months can trek from one end of Ladakh to the other, or even from places in Himachal Pradesh. The large number of trails and the limited number of roads allows one to string together routes that have road access often enough to restock supplies, but avoid walking on motor roads almost entirely.

Demographics

Ladakh has a population of about 260,000 constituting a blend of many different races, predominantly the Tibetans, Mons and the Dards. People of Dard descent predominate in Dras and Dha-Hanu areas. The residents of Dha-Hanu, known as Brokpa, practice Tibetan Buddhism and have preserved much of their original Dardic traditions and customs. The Dards around Dras, as an exception, have converted to Islam and have been strongly influenced by their Kashmiri neighbors. The Mons descend from earlier Indian settlers in Ladakh. They work as musicians, blacksmiths and carpenters.

Unlike the rest of mainly Islamic Jammu and Kashmir, most Ladakhis in Leh District as well as Zangskar Valley of Kargil District declare themselves Tibetan Buddhist, while most of the people in the rest of Kargil District declare Shia Muslims. Sizeable minorities of Buddhists live in Kargil District and Shia Muslims in Leh District. Some Sunni Muslims of Kashmiri descent live in Leh and Kargil towns, and also Padum in Zangskar. A few families of Ladakhi Christians, who converted in the nineteenth century, dwell there. Among descendants of immigrants, small numbers of followers of Hinduism, Sikhism, and the Bon religion, in addition to Buddhism, Islam and Christianity live. Most Buddhists follow the tantric form of Buddhism known as Vajrayana Buddhism. Shias mostly reside among the Balti and Purig people. Ladakhis generally come from Tibetan descent with some Dardic and Mon admixture.

The Changpa nomads, who live in the Rupshu plateau, closely relate to Tibetans. Since the early 1960s nomad numbers have increased as Chang Thang nomads from across the border flee Chinese-ruled Tibet. About 3,500 Tibetan refugees came from all parts of Tibet in Leh District. Since then, more than 2000 nomads, notably most of the community of Kharnak, have abandoned the nomadic life and settled in Leh town. Muslim Arghons, descendants of Kashmiri or Central Asian merchants and Ladakhi women, mainly live in Leh and Kargil towns. Like other Ladakhis, the Baltis of Kargil, Nubra, Suru Valley and Baltistan show strong Tibetan links in their appearance and language, and had been Buddhists until recent times.

Ladakhi constitutes the principal language of Ladakh. Ladakhi, a Tibetan dialect different enough from Tibetan that Ladakhis and Tibetans often speak Hindi or English when they need to communicate. Educated Ladakhis usually know Hindi/Urdu and often English. Within Ladakh, a range of dialects exists. The language of the Chang-pa people may differ markedly from that of the Purig-pa in Kargil, or the Zangskaris. Still, Ladakhi understand all the dialects. Due to its position on important trade routes, the racial composition as well as the language of Leh has been enriched. Traditionally, Ladakhi had no written form distinct from classical Tibetan, but recently a number of Ladakhi writers have started using the Tibetan script to write the colloquial tongue. People Administrative carry out work and education in English, although Urdu had been used to a great extent in the past and has been decreasing since the 1980s.

The total birth rate (TBR) in 2001 measured 22.44, with 21.44 for Muslims and 24.46 for Buddhists. Brokpas had the highest TBR at 27.17 and Arghuns had the lowest at 14.25. TFR measured 2.69 with 1.3 in Leh and 3.4 in Kargil. For Buddhists it numbered 2.79 and for Muslims 2.66. Baltis had a TFR of 3.12 and Arghuns had a TFR of 1.66. The total death rate (TDR) measured 15.69, with Muslims having 16.37 and Buddhists having 14.32. Brokpas numbered the highest at 21.74 and Bodhs the lowest at 14.32.[20]

| Year | Leh District (Population) | Leh District (Sex ratio) | Kargil District (Population) | Kargil District (Sex ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 40,484 (-) | 1011 | 41,856 (-) | 970 |

| 1961 | 43,587 (0.74) | 1010 | 45,064 (0.74) | 935 |

| 1971 | 51,891 (1.76) | 1002 | 53,400 (1.71) | 949 |

| 1981 | 68,380 (2.80) | 886 | 65,992 (2.14) | 853 |

| 2001 | 117,637 (2.75) | 805 | 115,287 (2.83) | 901 |

Culture

Ladakhi culture shares similarities with Tibetan culture. Ladakhi food has much in common with Tibetan food, the most prominent foods being thukpa, noodle soup; and tsampa, known in Ladakhi as ngampe, roasted barley flour. Edible without cooking, tsampa makes useful, if dull trekking food. Skyu, a heavy pasta dish with root vegetables, represents a dish strictly Ladakhi. As Ladakh moves toward a less sustainable cash-based economy, foods from the plains of India have become more common. Like in other parts of Central Asia, Ladakh's traditionally drink strong green tea with butter, and salt. They mix it in a large churn and known as gurgur cha, after the sound it makes when mixed. Sweet tea (cha ngarmo) commonly drunk now, follows the Indian style with milk and sugar. Ladakhi drink fermented barley, chang, an alcoholic beverage especially on festive occasions.[21]

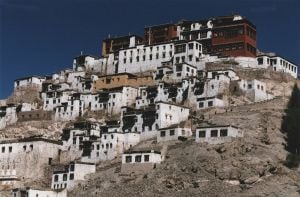

The architecture of Ladakh contains Tibetan and Indian influences, and monastic architecture reflects a deeply Buddhist approach. The Buddhist wheel, along with two dragons, constitutes a common feature on every gompa (including the likes of Lamayuru, Likir, Tikse, Hemis, Alchi and Ridzong Gompas). Many houses and monasteries have been built on elevated, sunny sites facing south, traditionally made of rocks, earth and wood. Contemporarily, house more often have concrete frames filled in with stones or adobes.

The music of Ladakhi Buddhist monastic festivals, like Tibetan music, often involves religious chanting in Tibetan or Sanskrit, as an integral part of the religion. Those complex chants often recite sacred texts or celebrate various festivals. Resonant drums and low, sustained syllables, accompany Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing.

Religious mask dances play an important part of Ladakh's cultural life. The Hemis monastery, a leading center of Drukpa Buddhism, serves as a center for an annual masked dance festival. The dances typically narrate a story of fight between good and evil, ending with the eventual victory of the former.[22] Weaving constitutes an important part of traditional life in eastern Ladakh. Both women and men weave, on different looms.[23] Typical costumes include Gonchas of velvet, elaborately embroidered waistcoats and boots, and hats. The Ladakh festival occurs every year in September. Performers, adorned with gold and silver ornaments and turquoise headgears throng the streets. Monks wear colorful masks and dance to the rhythm of cymbals, flutes and trumpets. The Yak, Lion and Tashispa dances depict the many legends and fables of Ladakh. Buddhist monasteries sporting prayer flags, display of 'thankas', archery competitions, a mock marriage, and horse-polo are the some highlights of this festival.

Archery constitutes a popular sport in Ladakh. Archery festivals, competitive events to which all the surrounding villages send their teams, take place during the summer months in villages. Conducted with strict etiquette, archery competitions take place to the accompaniment of the music of surna and daman (oboe and drum). King Singge Namgyal, whose mother had been a Balti princess, introduced Polo, the other traditional sport of Ladakh indigenous to Baltistan and Gilgit, into Ladakh in the mid-seventeenth century.[24]

The high status and relative emancipation enjoyed by women compared to other rural parts of India represents a feature of Ladakhi society that distinguishes it from the rest of the state. Fraternal polyandry and inheritance by primogeniture had been common in Ladakh until the early 1940s when government of Jammu and Kashmir made those illegal, although they still exist in some areas. In another custom commonly practiced, khang-bu or 'little house', the elders of a family, as soon as the eldest son has sufficiently matured, retire from participation in affairs. Taking only enough of the property for their own sustenance, they yield the headship of the family to him.[9]

Education

Traditionally the little formal education available took place in the monasteries. Usually, one son from every family mastered the Tibetan script to read the holy books.[9] The Moravian Mission opened the first school providing western education in Leh in October 1889, and the Wazir-i Wazarat of Baltistan and Ladakh ordered that every family with more than one child should send one of them to school. That order met with great resistance from the local people who feared that the children would be forced to convert to Christianity. The school taught Tibetan, Urdu, English, Geography, Sciences, Nature study, Arithmetic, Geometry and Bible study.

According to the 2001 census, the overall literacy rate in Leh District measures 62 percent (72 percent for males and 50 percent for females), and 58 percent in Kargil District (74 percent for males and 41 percent for females).[25] Schools spread evenly throughout Ladakh, but 75 percent of them provide only primary education. 65 percent of the children attend school, but absenteeism of both students and teachers remains high.

In both districts the failure rate at school-leaving level (class X) had for many years been around 85–95 percet, while of those managing to scrape through, barely half succeeded in qualifying for college entrance (class XII.) Before 1993, students learned in Urdu till they are 14 years old, after which the medium of instruction shifted to English. In 1994 the Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) launched 'Operation New Hope' (ONH), a campaign to provide 'culturally appropriate and locally relevant education' and make government schools more functional and effective. By 2001, ONH principles had been implemented in all the government schools of Leh District, and the matriculation exam pass rate had risen to 50 percent. A government degree college has been opened in Leh, enabling students to pursue higher education without having to leave Ladakh.[26] The Druk White Lotus School, located in Shey aims at helping to maintain the rich cultural traditions of Ladakh, while equipping the children for a life in the twenty-first century.

See also

| This article contains Indic text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks or boxes, misplaced vowels or missing conjuncts instead of Indic text. |

Notes

- ↑ Census 2001. Roof of the World. Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh (2001). Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Wiley, AS (2001). The ecology of low natural fertility in Ladakh. Department of Anthropology, Binghamton University (SUNY) 13902-6000, USA, PubMed publication. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- ↑ Ladakh map. jktourism.org. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ladakh History. jktourism.org. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ladakh. jktourism.org. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ladakh: People. jktourism.org. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ladakh culture. jktourism.org. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Janet Rizvi. 2001. Trans-Himalayan Caravans – Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. (New Delhi: Oxford Univ. Press)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Janet Rizvi. (1996). Ladakh - Crossroads of High Asia. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press/Oxford India Paperbacks, 2002. ISBN 0195645464)

- ↑ 2003 Kargil Council For Greater Ladakh. The Statesman, August 9, 2003, accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Charlie Loram. (2000) 2004. Trekking in Ladakh, 2nd Ed. (Trailblazer Publications)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Luciano Petech. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 C.E. (Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente). (in English)

- ↑ 1999. Glaciers Melt Despite Cooler Temperatures; Heat Mortality and Adaptation; Hurricanes on the Rise. Cooler Heads Coalition.

- ↑ Glacier man Chewang Norphel brings water to Ladakh. oneworld.net. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- ↑ Flora and fauna of Ladakh. India Travel Agents. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ Shadows in the Kingdom of Light, Ladakh and Global Economy. www.paulkingsnorth.net accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Garry Weare. 2002. Trekking in the Indian Himalaya, 4th ed. Lonely Planet

- ↑ Leh Ladakh Adventure tours and trekking. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ 2001, State Development Report—Jammu and Kashmir, Chapter 3A. Planning Commission of India. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ Population Dynamics: Problems and Prospects of High Altitude Area: Ladakh.

- ↑ Helena Norberg-Hodge. 2000. Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Oxford India Paperbacks

- ↑ Madhuri Guin, Masks: Reflections of Culture and Religion. Dolls of India. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ Monisha Ahmed. Living Fabric: Weaving Among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya, second ed. (Weatherhill, 2003. ISBN:9780834805217), [1] Powells.com. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ Ladakh culture. Jammu and Kashmir Tourism. accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ 2001 District-specific Literates and Literacy Rates. Education for all website accessdate 2008-07-22

- ↑ Education in Ladakh. Visit Ladakh Travel accessdate 2008-07-22

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allan, Nigel J. R. Karakorum Himalaya: Sourcebook for a Protected Area. Karachi: IUCN-The World Conservation Union, Pakistan, 1995. ISBN 9698141138 PDF. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- Cunningham, Alexander. Ladák, Physical, Statistical, and Historical, with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1998. ISBN 8120612965

- Drew, Federic. (1877) The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu, 1971. digitized text online, [2]. Internet archive. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- Francke, A. H. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Vol. 1: Personal Narrative; Vol. 2: The Chronicles of Ladak and Minor Chronicles, texts and translations, with Notes and Maps. Reprint 1972. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi, 1920, 1926. OCLC 1032045

- Gordon, Thomas Edward. The Roof of the World: Being a Narrative of a Journey Over the High Plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus Sources on Pamir. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1876. OCLC 679452

- Harvey, Andrew. A Journey in Ladakh. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0395340713

- Knight, E. F. Where Three Empires Meet; A Narrative of Recent Travel in Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the Adjoining Countries. London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1893. OCLC 1592758

- Loram, Charlie. (2000) 2004. Trekking in Ladakh, 2nd Ed. Trailblazer Publications. ISBN 1873756305.

- Moorcroft, William, George Trebeck, and H. H. Wilson. Travels in India: Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab, in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara from 1819 to 1825. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, 1989. OCLC 32281617

- Norberg-Hodge, Helena. Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. London: Rider Books, 2000.

- Peissel, Michel. The Ants' Gold: The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas. London: Harvill Press, 1984. ISBN 0002725142.

- Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 C.E. (Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente). (in English)

- Rizvi, Janet. Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0195640160

- __________. 2001. Trans-Himalayan Caravans – Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. New Delhi: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Weare, Garry. 2002. Trekking in the Indian Himalaya, 4th ed. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1740590856.

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2025.

- Ladakh District Leh-Ladakh

- The Druk White Lotus School

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.