Kargil War

| Kargil War | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indo-Pakistani Wars | |||||||||||

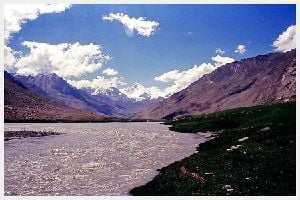

Mountains Kun and Nun in the distance. In Kargil district | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||||

Kashmiri secessionists, Islamic militants ("Foreign Fighters") | |||||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||||

| 30,000 | 5,000 | ||||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||||

| Indian Official Figures: 527 killed,[1][2][3] 1,363 wounded[4] 1 POW |

Pakistani Estimates:(II) 357‚Äď4,000+ killed[5][6] (Pakistan troops) 665+ soldiers wounded[5] 8 POWs.[7] | ||||||||||

The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict,(I) signifies an armed conflict between India and Pakistan that took place between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of Kashmir. The infiltration of Pakistani soldiers and Kashmiri militants into positions on the Indian side of the Line of Control, which serves as the de facto border between the two nations, caused the war. Directly after the war, Pakistan blamed the fighting entirely on independent Kashmiri insurgents. Documents left behind by casualties, and later statements by Pakistan's Prime Minister and Chief of Army Staff, showed involvement of Pakistani paramilitary forces. The Indian Army, supported by the Indian Air Force, attacked the Pakistani positions and, with international diplomatic support, eventually forced a Pakistani withdrawal across the Line of Control (LoC).

The war represents one of the most recent examples of high altitude warfare in mountainous terrain, and posed significant logistical problems for the combating sides. That constituted the first ground war between the two countries after they had developed nuclear weapons. (India and Pakistan both test-detonated fission devices in May 1998, though India conducted its first nuclear test in 1974.) The conflict led to heightened tensions between the two nations and increased defense spending on the part of India. In Pakistan, the aftermath caused instability to the government and the economy, and on October 12, 1999, a coup d'etat by the military placed army chief Pervez Musharraf in power.

| Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts |

|---|

| 1947 ‚Äď 1965 ‚Äď 1971 ‚Äď Siachen ‚Äď Kargil |

Location

Before the Partition of India in 1947, Kargil belonged to Gilgit-Baltistan, a region of diverse linguistic, ethnic and religious groups, due in part to the many isolated valleys separated by some of the world's highest mountains. The First Kashmir War (1947‚Äď1948) resulted in most of the Kargil region remaining an Indian territory; then, after Pakistan's defeat in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the remaining areas, including strategic military posts, also passed into Indian territory. Notably, Kargil alone has a Muslim majority among the district in the Ladakh subdivision. The town and district of Kargil sits in Jammu and Kashmir. The town lies on the Line of Control (LOC), the defacto border for the two nations, located 120 km (75 miles) from Srinagar, facing the Northern Areas. Like other areas in the Himalayas, it has a temperate climate, experiencing cool summers with frigid nights, with winters long and chilly, temperatures often dropping to ‚ąí40 ¬įC (‚ąí40 ¬įF). A national highway connecting Srinagar to Leh cuts through Kargil.

A 160 km long stretch on the border of the LOC, overlooking a vital highway on the Indian side of Kashmir constitutes the area that witnessed the infiltration and fighting. Apart from the district capital, Kargil, the front line in the conflict encompassed the tiny town of Drass as well as the Batalik sector, Mushko Valley and other nearby areas along the de facto border. The military outposts on these ridges generally stood approximately 5,000 metres (16,000 feet) high, with a few as high as 5,600 metres (18,000 feet). Pakistan targeted Kargil for incursions because its terrain lent itself to a pre-emptive seizure. With tactically vital features and well-prepared defensive posts atop the peaks, it provided an ideal high ground for a defender akin to a fortress. Any attack to dislodge the enemy and reclaim high ground in a mountain warfare would require a far higher ratio of attackers to defenders, further exacerbated by the high altitude and freezing temperatures. Additionally, Kargil sat just 173 km (108 mi) from the Pakistani controlled town of Skardu, enhancing logistical and artillery support to the Pakistani combatants. All those tactical reasons, plus the Kargil district having a Muslim majority, contributed to Pakistan's choice of Kargil as the location to attack.

Background

After the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, a long period of relative calm among the two neighbors ensued. During the 1990s, escalating tensions and conflict with separatists in Kashmir as well as nuclear tests by both countries in 1998 changed the scenario. Despite the belligerent atmosphere, both countries signed the Lahore Declaration in February 1999 to provide a peaceful and bilateral solution to the Kashmiri issue. In spite of that agreement, elements in the Military of Pakistan covertly trained and sent troops and paramilitary forces, some allegedly in the guise of mujahideen, into the Indian territory. They aimed to sever the link between Kashmir and Ladakh, and cause Indian forces to withdraw from the Siachen Glacier, thus forcing India to negotiate a settlement of the broader Kashmir dispute. Pakistan also believed that any tension in the region would internationalize the Kashmir issue, helping it to secure a speedy resolution. Yet another goal may have been to boost the morale of the decade-long rebellion in Indian Administered Kashmir by taking a proactive role. Some writers have speculated that the operation's objective may also have been as a retaliation for India's Operation Meghdoot in 1984 that seized much of Siachen Glacier.[8]

According to India's then army chief Ved Prakash Malik, and many other scholars, the infiltration went by the code name "Operation Badr",[9] and much of the background planning, including construction of logistical supply routes, had been undertaken much earlier. On more than one occasion, the army had given past Pakistani leaders (namely Zia ul Haq and Benazir Bhutto) similar proposals for an infiltration in the Kargil region in the 1980s and 1990s. The plans had been shelved for fear of drawing the nations into all-out war.[10][11] Some analysts believe that Pakistan reactivated the blueprint of attack with the appointment of Pervez Musharraf chief of army staff in October 1998. In a disclosure made by Nawaz Sharif, the then Prime Minister of Pakistan, he states that he had been unaware of the preparation of the intrusion, an urgent phone call from Atal Bihari Vajpayee, his counterpart in India, informed him about the situation.[12] Responding to that, Musharraf asserted that the Prime Minister had been briefed on the Kargil operation 15 days ahead of Vajpayee's journey to Lahore on February 20.[13] Sharif had attributed the plan to Musharraf and "just two or three of his cronies",[14] a view shared by some Pakistani writers who have stated that, only four generals, including Musharraf, knew of the plan.[10][15]

War progress

The Kargil War had three major phases. First, Pakistan captured several strategic high points in the Indian-controlled section of Kashmir. India responded by first capturing strategic transportation routes, then militarily pushing Pakistani forces back across the Line of Control.

Occupation by Pakistan

Because of the extreme winter weather in Kashmir, Indian and Pakistan Army commonly abandoned forward posts, reoccupying them in the spring. That particular spring, the Pakistan Army reoccupied the forward posts before the scheduled time.

In early May 1999, the Pakistan Army decided to occupy the Kargil posts, numbering around 130, and thus control the area. Troops from the elite Special Services Group as well as four to seven battalions[16][17] of the Northern Light Infantry (a paramilitary regiment distinct from the regular Pakistani army at that time) backed by Kashmiri guerrillas and Afghan mercenaries[18] covertly and overtly set up bases on the vantage points of the Indian-controlled region. Initially, those incursions went unnoticed due to the heavy artillery fire by Pakistan across the Line of Control, which provided cover for the infiltrators. But by the second week of May, the ambushing of an Indian patrol team, acting on a tip-off by a local shepherd in the Batalik sector, led to the exposure of the infiltration. Initially with little knowledge of the nature or extent of the encroachment, the Indian troops in the area claimed that they would evict them within a few days. Reports of infiltration elsewhere along the LoC made it clear that the entire plan of attack came on a much bigger scale. The total area seized by the ingress had been between 130 km² - 200 km²;[15][19] Musharraf stated that Pakistan occupied 500 Mi2 (1,300 km²) of Indian territory.[16]

The Government of India responded with Operation Vijay, a mobilization of 200,000 Indian troops. Because of the nature of the terrain, division and corps operations had to be suspended, with most fighting scaled back to the regimental or battalion level. In effect, two divisions of the Indian Army,[20] numbering 20,000, plus several thousand from the Indian Paramilitary Forces and the air force deployed in the conflict zone. The total number of Indian soldiers involved in the military operation on the Kargil-Drass sector numbered close to 30,000. The number of infiltrators, including those providing logistical backup, has been put at approximately 5000 at the height of the conflict.[15][21][18] That figure includes troops from Pakistan-administered Kashmir providing additional artillery support.

Protection of National Highway No. 1A

Kashmir has mountainous terrain at high altitudes; even the best roads, such as National Highway No. 1 (NH 1) from Leh to Srinagar, have only two lanes. The rough terrain and narrow roads slowed traffic, and the high altitude, affecting the ability of aircraft to carry loads, made control of NH 1A (the actual stretch of the highway under Pakistani fire) a priority for India. From their observation posts, the Pakistani forces had a clear line of sight to lay down indirect artillery fire on NH 1A, inflicting heavy casualties on the Indians.[22] That posed a serious problem for the Indian Army as the highway served as its main logistical and supply route. The Pakistani shelling of the arterial road posed the threat of Leh being cut off, though an alternative (and longer) road to Leh existed via Himachal Pradesh.

The infiltrators, apart from being equipped with small arms and grenade launchers, also had mortars, artillery and anti-aircraft guns. Many posts had been heavily mined, with India later recovering nearly 9,000 anti-personnel mines according to ICBL. Unmanned aerial vehicles and AN/TPQ-36 Firefinder radars supplied by the US performed Pakistan's reconnaissance. The initial Indian attacks aimed at controlling the hills overlooking NH 1A, with high priority being given to the stretches of the highway near the town of Kargil. The majority of posts along the Line of Control stood adjacent to the highway, and therefore the recapture of nearly every infiltrated post increased both the territorial gains and the security of the highway. The protection of that route and the recapture of the forward posts constituted ongoing objectives throughout the war. Though India had cleared most of the posts in the vicinity of the highway by mid-June, some parts of the highway near Drass witnessed sporadic shelling until the end of the war.

Indian territory recovery

Once India regained control of the hills overlooking NH 1A, the Indian Army turned to driving the invading force back across the Line of Control, but refrained from pursuing forces further into the Pakistani-controlled portion of Kashmir. The Battle of Tololing, among other assaults, slowly tilted the combat in India's favor. Some of the posts put up a stiff resistance, including Tiger Hill (Point 5140) that fell only later in the war. A few of the assaults occurred atop hitherto unheard of peaks‚ÄĒmost of them unnamed with only Point numbers to differentiate them‚ÄĒwhich witnessed fierce hand to hand combat. With the operation fully underway, about 250 artillery guns moved forward to clear the infiltrators in the posts standing in the line of sight. The Bofors field howitzer (infamous in India due to the Bofors scandal) played a vital role, with Indian gunners making maximum use of the terrain that assisted such an attack. Its success elsewhere had been limited due to the lack of space and depth to deploy the Bofors gun. The Indian military introduced aerial attacks in that terrain. The high altitude, which in turn limited bomb loads and the number of airstrips that could be used, limited the extend of the Indian Air Force's Operation Safed Sagar. The IAF lost a MiG-27 strike aircraft attributed to an engine failure as well as a MiG-21 fighter shot down by Pakistan. Pakistan said it shot down both jets after they crossed into its territory[23] and one Mi-8 helicopter to Stinger SAMs. During attacks the IAF used laser-guided bombs to destroy well-entrenched positions of the Pakistani forces. Estimates place the number of intruders killed by air action alone at nearly 700.[21]

In some vital points, neither artillery nor air power could dislodge the outposts manned by the Pakistan soldiers, positioned out of visible range. The Indian Army mounted some slow, direct frontal ground assaults that took a heavy toll given the steep ascent that had to be made on peaks as high as 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Since any daylight attack would be suicidal, all the advances had to be made under the cover of darkness, escalating the risk of freezing. Accounting for the wind chill factor, the temperatures often fell as low as ‚ąí11 ¬įC to ‚ąí15 ¬įC (12 ¬įF to 5 ¬įF) near the mountain tops. Based on military tactics, much of the costly frontal assaults by the Indians could have been avoided if the Indian Military had chosen to blockade the supply route of the opposing force, virtually creating a siege. Such a move would have involved the Indian troops crossing the LoC as well as initiating aerial attacks on Pakistan soil, a manoeuvre India rejected out of concern of expanding the theatre of war and reducing international support for its cause.

Meanwhile, the Indian Navy also readied itself for an attempted blockade of Pakistani ports (primarily Karachi port)[24] to cut off supply routes.[25] Later, the then-Prime Minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif disclosed that Pakistan had just six days of fuel to sustain itself if a full-fledged war had broken out.[21] As Pakistan found itself entwined in a prickly position, the army had covertly planned a nuclear strike on India, the news alarming U.S. President Bill Clinton, resulting in a stern warning to Nawaz Sharif.[26] Two months into the conflict, Indian troops had slowly retaken most of the ridges they had lost;[27][28] according to official count, an estimated 75‚Äď80 percent of the intruded area and nearly all high ground had come under Indian control.[29] Following the Washington accord on July 4, where Sharif agreed to withdraw the Pakistan-backed troops, most of the fighting came to a gradual halt. In spite of that, some of the militants still holed up refused to retreat, and the United Jihad Council (an umbrella for all extremist groups) rejected Pakistan's plan for a climb-down, instead deciding to fight on.[30] Following that, the Indian army launched its final attacks in the last week of July; as soon as the last of these Jihadists in the Drass subsector had been cleared, the fighting ceased on July 26. The day has since been marked as Kargil Vijay Diwas (Kargil Victory Day) in India. By the end of the war, India had resumed control of all territory south and east of the Line of Control, as established in July 1972 as per the Shimla Accord.

World opinion

Other countries criticized Pakistan for allowing its paramilitary forces and insurgents to cross the Line of Control.[31] Pakistan's primary diplomatic response, one of plausible deniability linking the incursion to what it officially termed as "Kashmiri freedom fighters," proved, in the end, unsuccessful. Veteran analysts argued that the battle, fought at heights where only seasoned troops could survive, placed the poorly equipped "freedom fighters" in an unwinable situation with neither the ability nor the wherewithal to seize land and defend it. Moreover, while the army had initially denied the involvement of its troops in the intrusion, two soldiers received the Nishan-E-Haider (Pakistan's highest military honor). Another 90 soldiers received gallantry awards, most of them posthumously, confirming Pakistan's role in the episode. India also released taped phone conversations between the Army Chief and a senior Pakistani general with the latter recorded saying: "the scruff of [the militants] necks is in our hands,"[32] although Pakistan dismissed it as a "total fabrication." Concurrently, Pakistan made several contradicting statements, confirming its role in Kargil, when it defended the incursions with the argument that the LOC remained under dispute.[33] Pakistan also attempted to internationalize the Kashmir issue, by linking the crisis in Kargil to the larger Kashmir conflict but, such a diplomatic stance found few backers on the world stage.[34]

As the Indian counter-attacks picked up momentum, Pakistani prime minister Nawaz Sharif flew to meet U.S. president Bill Clinton on July 4 to obtain support from the United States. Clinton rebuked Sharif, asking him to use his contacts to rein in the militants and withdraw Pakistani soldiers from Indian territory. Clinton would later reveal in his autobiography that "Sharif’s moves were perplexing" since the Indian prime minister had travelled to Lahore to promote bilateral talks aimed at resolving the Kashmir problem and "by crossing the Line of Control, Pakistan had wrecked the [bilateral] talks."[35] On the other hand, he applauded Indian restraint for stopping short of the LoC and escalating the conflict into an all-out war.[36] The other G8 nations, too, supported India and condemned the Pakistani violation of the LoC at the Cologne summit. The European Union opposed the violation of the LoC.[37] China, a long-time ally of Pakistan, refused to intervene in Pakistan's favor, insisting on a pullout of forces to the LoC and settling border issues peacefully. Other organizations like the ASEAN Regional Forum too supported India's stand on the inviolability of the LOC.[34] Faced with growing international pressure, Sharif managed to pull back the remaining soldiers from Indian territory. The joint statement issued by Clinton and Sharif conveyed the need to respect the Line of Control and resume bilateral talks as the best forum to resolve all disputes.[38]

Impact and influence of media

The Kargil War significantly impacted and influenced the mass media in both nations, especially on the Indian side. Coming at a time of exploding growth in electronic journalism in India, the Kargil news stories and war footage often broadcast live footage on TV, and many websites provided in-depth analysis of the war. The conflict became the first "live" war in South Asia given such detailed media coverage, often to the extent of drumming up jingoistic feelings. The conflict soon turned into a news propaganda war, with the official press briefings of both nations producing claims and counterclaims. It reached such a stage where an outside observer listening to both Indian as well as Pakistani coverage of the conflict, would wonder whether both sides reported on the same conflict. The Indian government placed a temporary news embargo on information from Pakistan, even banning the telecast of the state-run Pakistani channel PTV and blocked access to online editions of Dawn newspaper. The Pakistani media played up that apparent curbing of freedom of the press in India, while the latter claimed national security concerns.

As the war progressed, media coverage became more intense in India compared to Pakistan. Many Indian channels showed images from the battle zone with their troops in a style reminiscent of CNN's coverage of the Gulf War. The proliferation of numerous privately owned channels vis-à-vis the Pakistani electronic media scenario, still at a nascent stage, constituted one of the reasons for India's increased coverage. The relatively greater transparency in the Indian media represented a second reason. At a seminar in Karachi, Pakistani journalists agreed that while the Indian government had taken the press and the people into its confidence, Pakistan refused allowing transparent coverage to its people.[39] The Indian government also ran advertisements in foreign publications like The Times and The Washington Post detailing Pakistan's role in supporting extremists in Kashmir in an attempt to garner political support for its cause during the combat. The print media in India and abroad took a stand largely sympathetic to the Indian cause, with editorials in newspapers based in the west and other neutral countries observing that Pakistan bore the lion's share of responsibility for the incursions. Analysts believe that the power of the Indian media, both larger in number and reputed more credible, might have acted as a force multiplier for the Indian military operation in Kargil, and served as a morale booster. As the fighting intensified, the Pakistani version of events found little backing on the world stage, helping India to gain valuable diplomatic recognition for its position on the issue.

WMDs and the nuclear factor

Both countries possession of nuclear weapons, and that an escalated war could have led to nuclear war, concerned in the international community during the Kargil crisis. Both countries had tested their nuclear capability a year before in 1998; India conducted its first test in 1974 while the 1998 blast represented Pakistan's first-ever nuclear test. Many pundits believed the tests an indication of the escalating stakes in the scenario in South Asia. With the outbreak of clashes in Kashmir just a year after the nuclear tests, many nations took notice of the conflict and desired to end it.

The first hint of the possible use of a nuclear bomb came on May 31 when Pakistani foreign secretary Shamshad Ahmad made a statement warning that an escalation of the limited conflict could lead Pakistan to use "any weapon" in its arsenal.[40] An obvious threat of a nuclear retaliation by Pakistan in the event of an extended war, the leader of Pakistan's senate noted, "The purpose of developing weapons becomes meaningless if they are not used when they are needed." Many such ambiguous statements from officials of both countries portended an impending nuclear crisis. The limited nuclear arsenals of both sides, paradoxically could have led to 'tactical' nuclear warfare in the belief that a nuclear strike would stop short of total nuclear warfare with mutual assured destruction, as could have occurred between the United States and the USSR. Some experts believe that following nuclear tests in 1998, Pakistani military felt emboldened by its nuclear deterrent cover to markedly increase coercion against India.[41]

The nature of the India-Pakistan conflict took a more sinister proportion when the U.S. received intelligence that Pakistani nuclear warheads moved towards the border. Bill Clinton tried to dissuade Pakistan prime minister Nawaz Sharif from nuclear brinkmanship, even threatening Pakistan with dire consequences. According to a White House official, Sharif seemed genuinely surprised by the alleged missile movement, responding that India probably planned the same action. An article in May 2000, stating that India too had readied at least five nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles, later confirmed the story.[42] Sensing a deteriorating military scenario, diplomatic isolation, and the risks of a larger conventional and nuclear war, Sharif ordered the Pakistani army to vacate the Kargil heights. He later claimed in his official biography that General Pervez Musharraf had moved nuclear warheads without informing him. Recently, Pervez Musharraf revealed in his memoirs that Pakistan’s nuclear delivery system had been unoperational during the Kargil war;[16] something that would have put Pakistan under serious disadvantage if the conflict went nuclear.

Additionally, the threat of WMD included a suspected use of chemical and even biological weapons. Pakistan accused India of using chemical weapons and incendiary weapons such as napalm against the Kashmiri fighters. India, on the other hand, showcased a cache of gas masks, among other firearms, as proof that Pakistan may have been prepared to use non-conventional weapons. One militant group even claimed to possess chemical weapons, later determined a hoax, and even the gas masks had been likely intended by the Pakistanis as protection from an Indian attack. The Pakistani allegations of India using banned chemicals in its bombs proved unfounded by the U.S. administration at the time and the OPCW.[43]

Aftermath

India

The aftermath of the war saw the rise of the Indian stock market by over 30 percent. The next Indian national budget included major increases in military spending. From the end of the war until February 2000, the India enjoyed a bullish economy. Patriotism surged with many celebrities pitching in towards the Kargil cause.[44] Indians felt angered by the death of pilot Ajay Ahuja under controversial circumstances, and especially after Indian authorities reported that Ahuja had been murdered and his body mutilated by Pakistani troops. The war had also produced higher than expected fatalities for the Indian military, with a sizable percentage of them including newly commissioned officers. One month later, the Atlantique Incident - in which India shot down a Pakistan Navy plane - briefly reignited fears of a conflict between the two countries.

After the war, the Indian government severed ties with Pakistan and increased defense preparedness. Since the Kargil conflict, India raised its defense budget as it sought to acquire more state of the art equipment. A few irregularities came to light during that period of heightened military expenditure.[45] Severe criticism of the intelligence agencies like RAW arose, which failed to predict either the intrusions or the identity/number of infiltrators during the war. An internal assessment report by the armed forces, published in an Indian magazine, showed several other failings, including "a sense of complacency" and being "unprepared for a conventional war" on the presumption that nuclearism would sustain peace. It also highlighted the lapses in command and control, the insufficient troop levels and the dearth of large-calibre guns like the Bofors.[46] In 2006, retired Air Chief Marshal, A.Y. Tipnis, alleged that the Indian Army failed to fully inform the government about the intrusions, adding that the army chief Ved Prakash Malik, refrained from using full strike capability of the Indian Air Force initially, instead requesting only helicopter gunship support.[47] Soon after the conflict, India also decided to complete the project‚ÄĒpreviously stalled by Pakistan‚ÄĒto fence the entire LOC.

The 13th Indian General Elections to the Lok Sabha, which gave a decisive mandate to the NDA government, followed the Kargil victory, re-elected to power in Sept‚ÄďOct 1999 with a majority of 303 seats out of 545 in the Lok Sabha. On the diplomatic front, the conflict provided a major boost to Indo-U.S. relations, as the United States appreciated Indian attempts to restrict the conflict to a limited geographic area. Those ties further strengthened following the 9/11 attacks and a general shift in foreign policy of the two nations. Relations with Israel ‚Äď which had discreetly aided India with ordnance supply and mat√©riel such as unmanned aerial vehicles and laser-guided bombs, as well as satellite imagery ‚Äď also strengthened following the end of the conflict.[48]

Pakistan

Faced with the possibility of international isolation, the already fragile Pakistani economy weakened further.[49][50] The morale of its forces after the withdrawal declined[51] as many units of the Northern Light Infantry suffered annihilation,[52] and the government refused to even recognize the dead bodies of its soldiers,[53] an issue that provoked outrage and protests in the Northern Areas.[54] Pakistan initially refused to acknowledge many of its casualties, but Sharif later said that over 4000 Pakistani troops died in the operation and that Pakistan had lost the conflict. Responding to that, Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf said, "It hurts me when an ex-premier undermines his own forces," and claimed that India suffered more casualties than Pakistan.[55]

Many in Pakistan had expected a victory over the Indian military based on Pakistani official reports on the war,[49] but felt dismay by the turn of events and questioned the eventual retreat.[10][56] Some believe the military leadership felt let down by the prime minister's decision to withdraw the remaining fighters. Author authors, including ex-CENTCOM Commander Anthony Zinni, and ex-PM Nawaz Sharif, state that the General requested Sharif to withdraw the Pakistani troops.[57] With Sharif placing the onus of the Kargil attacks squarely on the army chief Pervez Musharraf, an atmosphere of uneasiness existed between the two. On October 12, 1999, General Musharraf staged a bloodless coup d'état, ousting Nawaz Sharif.

Benazir Bhutto, an opposition leader and former prime minister, called the Kargil War "Pakistan's greatest blunder." Many ex-officials of the military and the ISI (Pakistan's principal intelligence agency) also held the view that "Kargil was a waste of time" and "could not have resulted in any advantage" on the larger issue of Kashmir. The Pakistani media voiced criticism of the whole plan and the eventual climbdown from the Kargil heights with no gains to show for the loss of lives, only international condemnation for its actions.[58]

Despite calls by many for a probe, the Pakistani government failed to set up a public commission of inquiry to investigate the people responsible for initiating the conflict. The Pakistani political party, PML(N) unveiled a white paper in 2006, stating that Nawaz Sharif constituted an inquiry committee that recommended a court martial for General Pervez Musharraf.[59] The party alleges that Musharraf "stole the report" after toppling the government, to save himself. The report also claims that India knew about the plan eleven months before its launch, enabling a complete victory for India on military, diplomatic and economic fronts.[60] Though the Kargil conflict had brought the Kashmir dispute into international focus ‚Äď one of Pakistan's aims ‚Äď it had done so in negative circumstances that eroded its credibility, since the infiltration came just after a peace process between the two countries initiated. The sanctity of the LoC too received international recognition.

After the war, the army made a few changes. In recognition of the Northern Light Infantry's performance in the war - which even drew praise from a retired Indian Lt. General[22] - the regiment incorporated into the regular army. The war showed that despite a tactically sound plan that had the element of surprise, little groundwork had been done to gauge the politico-diplomatic ramifications.[61] And like previous unsuccessful infiltrations attempts like Operation Gibraltar that sparked the 1965 war, the branches of the Pakistan military enjoyed little coordination or information sharing. One U.S. Intelligence study states that Kargil served as yet another example of Pakistan’s (lack of) grand strategy, repeating the follies of the previous wars.[62] All those factors contributed to a strategic failure for Pakistan in Kargil.

Kargil War in the arts

The brief conflict has provided considerable material for both filmmakers and authors alike in India. The ruling party coalition, led by BJP, used some documentaries shot on the subject in furthering its election campaign that immediately followed the war. A list of the major films and dramas on the subject follows.

- LOC: Kargil (2003), a Hindi movie depicting most of the incidents from the Kargil War, stands as one of the longest in Indian movie history running for more than four hours.

- Lakshya (2004), a Hindi movie portraying a fictionalized account of the conflict. Movie critics have generally appreciated the realistic portrayal of characters.[63] The film also received good reviews in Pakistan because it portrays both sides fairly.

- Dhoop (2003), directed by national award winner Ashwini Chaudhary, which depicted the life of Anuj Nayyar's parents after his death. Anuj Nayyar, a captain in the Indian army, received the Maha Vir Chakra award posthumously. Om Puri plays the role of S.K. Nayyar, Anuj's father.

- Mission Fateh - Real Stories of Kargil Heroes, a TV series telecast on Sahara channel chronicling the Indian Army's missions.

- Fifty Day War - A theatrical production on the war, the title indicating the length of the Kargil conflict. Claimed as the biggest production of its kind in Asia, involving real aircraft and explosions in an outdoor setting.

Many other movies like Tango Charlie also drew heavily upon the Kargil episode, continuing as a plot for mainstream movies with a Malayalam movie Keerthi Chakra, being based on an incident in Kargil. The impact of the war in the sporting arena appeared during the India-Pakistan clash in the 1999 Cricket World Cup, which coincided with the Kargil timeline. The game witnessed heightened passions, becoming one of the most viewed matches in the tournament.

Commentary

Note (I): Names for the conflict: Various names for the conflict have emerged. During the actual fighting in Kargil, the Indian Government carefully avoided the term "war," calling it a "war-like situation," even though both nations declared themselves in a "state of war." Terms like Kargil "conflict," Kargil "incident" or the official military assault, "Operation Vijay," emerged as preferred terms. After the end of the war, the Indian Government increasingly called it the "Kargil War," even without an official declaration of war. Other less popularly used names included "Third Kashmir War" and Pakistan's codename given to the infiltration: "Operation Badr."

Note (II): Casualties: The exact count of Pakistan army losses has been more difficult to figure out, partly because Pakistan has not yet published an official casualties list. The US Department of State had made an early, partial estimate of close to 700 fatalities. After the end of the war, scholars revised that figure upwards. Estimates on Pakistan casualties vary wildly given the problems of assessing the number of deaths in the militant ranks. According to Nawaz Sharif's statements, Pakistan suffered 4,000+ fatalities. His party Pakistan Muslim League (N) in its "white paper" on the war mentioned that more than 3,000 Mujahideens, officers and soldiers killed.[64] The PPP, assessed the casualties as 3000 soldiers and irregulars, as given [2] on their website. Indian estimates, as stated by the country's Army Chief mention 1,042 Pakistani soldiers killed. Musharraf, in his Hindi version of his memoirs, titled "Agnipath," differs from all the estimates, stating that 357 troops died with a further 665 wounded.[5] Apart from General Musharraf's figure on the number of Pakistanis wounded, the number of people injured in the Pakistan camp remains undetermined.

Notes

All links Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- ‚ÜĎ Government of India site mentioning the Indian casualties, Statewise break up of Indian casualties statement from Indian Parliament. government of India.

- ‚ÜĎ Breakdown of causalities into Officers, JCOs, and Other Ranks - Parliament of India Website]

- ‚ÜĎ Complete Roll of Honour of Indian Army's Killed in Action during Op Vijay. Official Indian Army Website.

- ‚ÜĎ Official statement giving breakdown of wounded personnel - Parliament of India Website

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 5.2 President Musharaffs disclosure on Pakistani Casualties in his book. Indian Express. Aug 17, 2003

- ‚ÜĎ Over 4000 soldier's killed in Kargil: Sharif. the Hindu.

- ‚ÜĎ Tribune Report on Pakistani POWs. tribuneindia.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Robert G. Wirsing. Kashmir in the Shadow of War: regional rivalries in a nuclear age. (M.E. Sharpe, 2003. ISBN 0765610906), 38

- ‚ÜĎ Kargil: where defense met diplomacy - Hosted on Daily Times; The Fate of Kashmir By Vikas Kapur and Vipin Narang. Stanford Journal of International Relations; Book review of "The Indian Army: A Brief History by Maj Gen Ian Cardozo" - Hosted on IPCS

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hassan Abbas. Pakistan's Drift Into Extremism: Allah, the Army, and America's War on Terror. (M.E. Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 0765614979)

- ‚ÜĎ Musharraf advised against Kargil, says Benazir, Musharraf had brought Kargil plan to me: Benazir, Interview in 2003. ‚ÄėMusharraf planned Kargil when I was PM‚Äô: Bhutto - Previous interview to Hindustan Times on November 30, 2001.

- ‚ÜĎ I was in dark about Kargil aggression: Sharief. July 16, 2004 - Hosted on Rediff.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Kargil planned before Vajpayee's visit: Musharraf. July 13, 2006 - Indian Express.

- ‚ÜĎ I learnt about Kargil from Vajpayee, says Nawaz. Dawn, May 29, 2006. accessdate 2006-05-29

- ‚ÜĎ 15.0 15.1 15.2 An Analysis of the Kargil Conflict 1999, by Brigadier Shaukat Qadir, RUSI Journal, April 2002. ccc.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Pervez Musharraf. In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. (New York: Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743283449)

- ‚ÜĎ Ravi Rikhye, The Northern Light Infantry in the Kargil Operations by Ravi Rikhye 1999 August 25, 2002 - ORBAT.

- ‚ÜĎ 18.0 18.1 The estimate of 2000 "Mujahideen" involved originated with Musharraf's statement on July 06, 1999, to Pakistan's The News; online article in the Asia Times quoting the General's estimate. An Indian Major General(retd) too puts the number of guerrillas at 2,000 apart from the NLI Infantry Regiment.

- ‚ÜĎ War in Kargil (PDF); Islamabad Playing with Fire by Praful Bidwai - The Tribune, June 7, 1999

- ‚ÜĎ Lessons from Kargil, Gen VP Malik. BHARAT RAKSHAK MONITOR 4(6) (May-June 2002)

- ‚ÜĎ 21.0 21.1 21.2 1999 Kargil Conflict -GlobalSecurity.org

- ‚ÜĎ 22.0 22.1 Indian general praises Pakistani valour at Kargil May 5, 2003, Daily Times, Pakistan.

- ‚ÜĎ India loses two jets. BBC News.

- ‚ÜĎ The Resurgence of Baluch nationalism by Fr√©d√©ric Grare. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ‚ÜĎ Cdr. (Retd) Muhammad Azam Khan, [1] "Exercise Seaspark‚ÄĒ2001." Defence Journal, April 2001

- ‚ÜĎ Pakistan 'prepared nuclear strike' BBC News, May 16, 2002.

- ‚ÜĎ Tariq Ali, Bitter Chill of Winter. London Review of Books, April 19, 2001.

- ‚ÜĎ Colonel Ravi Nanda. Kargil: A Wake Up Call. (Vedams Books, 1999. ISBN 8170950740)

- ‚ÜĎ Kargil: where defense met diplomacy - India's then Chief of Army Staff V.P. Malik, expressing his views on Operation Vijay in an article in The Indian Express.

- ‚ÜĎ Pakistan and the Kashmir militants. BBC News.

- ‚ÜĎ Hassan Abbas. Pakistan's Drift Into Extremism: Allah, The Army, And America's War On Terror. (M.E. Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 0765614979), 173; Revisiting Kargil: Was it a Failure for Pakistan's Military?, IPCS.

- ‚ÜĎ Transcripts of conversations between Lt Gen Mohammad Aziz, Chief of General Staff and Musharraf. India Today.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. brokers Kargil peace but problems remain, Betrayal on Kargil by Nasim Zehra. jang. June 16, 2000

- ‚ÜĎ 34.0 34.1 ASEAN backs India's stand July 24, 2006 The Tribune.

- ‚ÜĎ Bill Clinton. My Life. (Random House, 2004. ISBN 0375414576), 865

- ‚ÜĎ Dialogue call amid fresh fighting BBC News, July 21, 1999

- ‚ÜĎ India encircles rebels on Kashmir mountaintop - CNN.

- ‚ÜĎ Text of joint Clinton-Sharif statement. Reuters.

- ‚ÜĎ Pak media lament lost opportunity - Editorial statements and news headlines from Pakistan hosted on Rediff.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Quoted in News Desk, ‚ÄúPakistan May Use Any Weapon,‚ÄĚ The News, May 31, 1999.

- ‚ÜĎ Options Available to the United States to Counter a Nuclear Iran By George Perkovich - Testimony by George Perkovich before the House Armed Services Committee, February 1, 2006. carnegieendowment.org.

- ‚ÜĎ "India had deployed Agni during Kargil," Article from Indian Express, June 19, 2000.

- ‚ÜĎ NTI:Country Overview - The Nuclear Threat Initiative.

- ‚ÜĎ MEENAKSHI GANGULY, New Delhi, The Spoils of War. TIME magazine,¬†;India backs its 'boys'. BBC News.

- ‚ÜĎ Kargil defense purchases scandal. rediff.com.¬†; Kargil coffin scam. tribuneindia.com.

- ‚ÜĎ "War Against Error," (Cover story) on Outlook, February 28, 2005, Online edition.

- ‚ÜĎ Army was reluctant to tell govt about Kargil: Tipnis. October 7, 2006 - The Times of India.

- ‚ÜĎ News reports from Daily Times (Pakistan); Sunil Raman, Sharon's historic India visit. BBC News mentioning the Israeli military support to India during the conflict.

- ‚ÜĎ 49.0 49.1 Samina Ahmed. "Diplomatic Fiasco: Pakistan's Failure on the Diplomatic Front Nullifies its Gains on the Battlefield". (Belfer Center for International Affairs, Kennedy School of Government)

- ‚ÜĎ Multiple views and opinions on the state of Pakistan's economy, the Kashmir crisis and the military coup, salon.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Samina Ahmed. "A Friend for all Seasons." (Belfer Center for International Affairs, Kennedy School of Government)

- ‚ÜĎ War in Kargil - The CCC's summary on the war.

- ‚ÜĎ "Pakistan refuses to take even officers' bodies". Rediff.com.

- ‚ÜĎ Musharraf and the truth about Kargil - The Hindu September 25, 2006.

- ‚ÜĎ President Musharraf reacts to Nawaz Sharif's Pakistan's casualty claims in Kargil. expressindia.

- ‚ÜĎ Pakistani opposition presses for Sharif's resignation By K. Ratnayake 7 August 1999, Can Sharif deliver?, Michael Krepon. "The Stability-Instability Paradox in South Asia" - Hosted on Henry L. Stimson Centre.

- ‚ÜĎ Tom Clancy, Gen. Tony Zinni (Retd), and Tony Koltz. Battle Ready. Grosset & Dunlap, 2004. ISBN 0399151761

- ‚ÜĎ Victory in reverse: the great climbdown. Dawn, For this submission what gain? by Ayaz Amir - Dawn

- ‚ÜĎ PML-N issues white paper on Kargil operation - The News International.

- ‚ÜĎ Ill-conceived planning by Musharraf led to second major military defeat in Kargil: PML-N Pak Tribune, August 6 2006

- ‚ÜĎ Kargil: the morning after By Irfan Husain April 29, 2000, Dawn.

- ‚ÜĎ EDITORIAL: Kargil: a blessing in disguise? July 19, 2004 Daily Times, Pakistan.

- ‚ÜĎ A collection of some reviews on the movie "Lakshya". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ‚ÜĎ Ill-conceived planning by Musharraf led to second major military defeat in Kargil: PML-N. PakTribune, August 6, 2006,

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abbas, Hassan. Pakistan's Drift Into Extremism: Allah, the Army, and America's War on Terror. M.E. Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 0765614979

- Akbar, M. K. Kargil Cross Border Terrorism. South Asia Books, 1999. ISBN 8170997348

- Ayub, Muhammad. An Army; Its role and Rule: A History of the Pakistan Army From Independence to Kargil 1947‚Äď1999. Rosedog Books, 2005. ISBN 0805995943

- Clancy, Tom, Gen. Tony Zinni (Retd), and Tony Koltz. Battle Ready. Grosset & Dunlap, 2004. ISBN 0399151761

- Cohen, Stephen P. The Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press, 2004. ISBN 0815715021

- Dixit, J. N. India-Pakistan in War & Peace. Books Today, 2002. ISBN 0415304725

- Kargil Review Committee. From Surprise to Reckoning: The Kargil Review Committee Report. SAGE Publications, 2000. ISBN 0761994661. (Executive summary of the report, Online)

- Musharraf, Pervez. In the Line of Fire: A Memoir. New York: Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743283449

- Singh, Amarinder. A Ridge Too Far: War in the Kargil Heights. New Delhi: Motibagh Palace, 2001. ASIN: B0006E8KKW

- Singh, Jasijit. Kargil 1999: Pakistan's Fourth War for Kashmir. South Asia Books, 1999. ISBN 8186019227

- Wirsing, Robert G. Kashmir in the Shadow of War: regional rivalries in a nuclear age. M.E. Sharpe, 2003. ISBN 0765610906

External links

All links retrieved February 28, 2025.

- Impact of the conflict on civilians: BBC.

- Video of Pakistani PoWs from the conflict hosted on YouTube.

- Video on Tiger Hill operations by IAF - National Geographic Channel video..

- Limited Conflict Under the Nuclear Umbrella: RAND Corporation.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.