Codex Sinaiticus

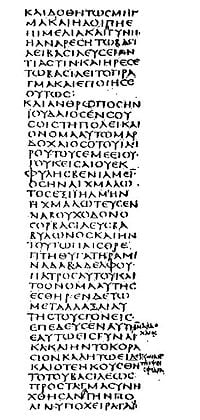

Codex Sinaiticus is one of the most important hand-written ancient copies of the Greek Bible. It was written in the fourth century C.E., in uncial script (Capital letters). It came to the attention of scholars in the nineteenth century at the Greek Monastery of Mount Sinai, with further material discovered in the twentieth century, and most of it is today in the British Library.[1] Originally, it contained the whole of both Testaments. The Greek Old Testament (or Septuagint) survived almost complete, along with a complete New Testament, plus the Epistle of Barnabas, and portions of The Shepherd of Hermas.[1]

Along with Codex Vaticanus, Codex Sinaiticus is one of the most valuable manuscripts for establishing the original text of the Greek New Testament, as well as the Septuagint. It is the only uncial manuscript with the complete text of the New Testament, and the only ancient manuscript of the New Testament written in four columns per page which has survived to the present day.[1]

Description

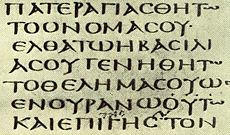

The work was written in scripta continua with neither breathings nor polytonic accents. Occasional points and few ligatures are used, though nomina sacra with overlines are employed throughout. Each line has some 12 to 14 Greek uncial letters, arranged in four columns (48 lines in column) with carefully-chosen line breaks and slightly ragged right edges. The poetical books of the Old Testament written in στίχοι, only in two columns per page. Breathings and accents there are none. The codex has almost four million uncial letters.

Each rectangular page has the proportions 1.1 to 1, while the block of text has the reciprocal proportions, 0.91 (the same proportions, rotated 90°). If the gutters between the columns were removed, the text block would mirror the page's proportions. Typographer Robert Bringhurst referred to the codex as a "subtle piece of craftsmanship".[2]

The folios are made of vellum parchment made from donkey or antelope skin. Most of the quires or signatures contain four leaves save two containing five.

The portion of the codex held by the British Library consists of 346½ folios, 694 pages (38.1 cm x 34.5 cm), constituting over half of the original work. Of these folios, 199 belong to the Old Testament including the apocrypha and 147½ belong to the New Testament, along with two other books, the Epistle of Barnabas and part of The Shepherd of Hermas. The apocryphal books present in the surviving part of the Septuagint are 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 4 Maccabees, Wisdom and Sirach[3]. The books of the New Testament are arranged in this order: the four Gospels, the epistles of Paul (Hebrews follows 2 Thess), the Acts of the Apostles,[4] the General Epistles, and the Book of Revelation. The fact that some parts of the codex are preserved in good condition, while others are in very poor condition, implies they were separated and stored in two places.

The text of the codex

Text-type and relationship to other manuscripts

For most of the New Testament, Codex Sinaiticus is in general agreement with Codex Vaticanus and Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, attesting the Alexandrian text-type. A notable example of an agreement between the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus texts is that they both omit the word εικη ('without cause', 'without reason', 'in vain') from Matthew 5:22 "But I say unto you, That whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment."[5]

Only in John 1:1-8:38 Codex Sinaiticus represents different text-type than Vaticanus and any other Alexandrian manuscript. It is in closer agreement with Codex Bezae in support of the Western text-type. F.e. in John 1:3 Sinaiticus and Codex Bezae are only Greek manuscripts with textual variant ἐν αὐτῷ ζωὴ ἐστίν (in him is life) instead of ἐν αὐτῷ ζωὴ ᾓν (in him was life). This variant is supported by Vetus Latina and some Sahidic manuscripts. This portion has a large number of corrections.[6] However, there are a number of differences between Sinaiticus and Vaticanus. Hoskier enumerated 3036 differences:

- Matt – 656

- Mark – 567

- Luke – 791

- John – 1022

- Together—3036.[7]

A large number of these differences is a result of iotacisms, and a different way for a transcription of Hebrew names. These two manuscripts were not written in the same scriptorium. According to Hort Sinaiticus and Vaticanus were derived from a common original much older, "the date of which cannot be later than the early part of the second century, and may well be yet earlier".[8] The following example illustrates the differences between Sinaiticus and Vaticanus in Matt 1:18-19:

| Codex Sinaiticus | Codex Vaticanus |

|---|---|

| Του δε ΙΥ ΧΥ η γενεσις ουτως ην μνηστευθισης της μητρος αυτου Μαριας τω Ιωσηφ πριν ην συνελθιν αυτους ευρεθη εν γαστρι εχουσα εκ ΠΝΣ αγιου Ιωσηφ δε ο ανηρ αυτης δικαιος ων και μη θελων αυτην παραδιγματισαι εβουληθη λαθρα απολυσαι αυτην |

Του δε ΧΥ ΙΥ η γενεσις ουτως ην μνηστευθεισης της μητρος αυτου Μαριας τω Ιωσηφ πριν ην συνελθειν αυτους ευρεθη εν γαστρι εχουσα εκ ΠΝΣ αγιου Ιωσηφ δε ο ανηρ αυτης δικαιος ων και μη θελων αυτην δειγματισαι εβουληθη λαθρα απολυσαι αυτην |

Burnett Hillman Streeter remarked a great agreement between codex and Vulgate of Jerome. According to him Origen brought to Caesarea the Alexandrian text-type which was used in this codex, and used by Jerome.[9]

Since the fourth to the twelfth century worked on this codex 9 correctors and it is one of the most corrected manuscripts.[10] Tischendorf enumerated 14,800 corrections. Besides of this corrections some letters were marked by dot as doubtfull (f.e. ṪḢ). Corrections represent Byzantine text-type, just like in codices: Bodmer II, Regius (L), Ephraemi (C), and Sangallensis (Δ). They were discovered by Cambridge scholar Edward A. Button.[11]

Lacunae

The text of the Old Testament is missing the following passages:

The text of New Testament omitted several passages:

- Omitted verses

- Gospel of Matthew 6:2-3, 6:2-3, 12:47, 17:21, 18:11, 23:14

- Gospel of Mark 7:16, 9:44, 9:46, 11:26, 15:28, 16:8-20(Mark's ending)

- Gospel of Luke 10:32, 17:36, 22:43-44(marked by the first corrector as doubtful, but a third corrector removed that mark)

- Gospel of John 9:38, 5:4, 7:53-8:11 (Pericope adulterae), 16:15, 21:25

- Acts of the Apostles 8:37, 15:34,24:7, 28:29

- Epistle to the Romans 16:24

- Omitted phrases

- Mark 1:1 "the Son of God" omitted.

- Matthew 6:13 "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen." omitted.

- Luke 9:55-56 "Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of. For the Son of man is not come to destroy men's lives, but to save them" omitted.

- For a complete list of omitted phrases in the Codex Sinaiticus, see List of omitted Bible verses in the New Testament#List of omitted Bible phrases

These omissions are typical for the Alexandrian text-type.

Unique textual variants

In Matt 13:54 εις την πατριδα αυτου changed into εις την αντιπατριδα αυτου, and in Acts 8:5 εις την πολιν της Σαμαρειας replaced into εις την πολιν της Καισαριας. This two variants do not exist in any other manuscripts, and it seems they were made by a scribe. According to T. C. Skeat, they suggest Caesarea as a place in which manuscript was made.[12]

History of the codex

Early history of codex

Of its early history, little is known of the text. It may have been written in Rome, Egypt, or Caesarea during the fourth century C.E. It could not be written before 325 C.E. because it contains the Eusebian Canons, and it is a terminus a quo. It can not be written after 350 C.E. because references to the Church fathers on a margin notes exclude that possibility. Therefore, the date 350 C.E. is a terminus ad quem. The document is said to be was one of the fifty copies of the Bible commissioned from Eusebius by Roman Emperor Constantine after his conversion to Christianity (De vita Constantini, IV, 37).[13] This hypothesis was supported by T. C. Skeat.[14]

Tischendorf believed four separate scribes copied the work (whom he named A, B, C, and D), and seven correctors amended portions, one of them contemporaneous with the original scribes, the others dating to the sixth and seventh centuries. Modern analysis identifies at least three scribes. Scribe B was poor speller, scribe A was not very much better, the best was scribe D. Scribe A wrote most of the historical and poetical books of the Old Testament, and almost the whole of the New Testament.

A paleographical study at the British Museum in 1938 found that the text had undergone several corrections. The first corrections were done by several scribes before the manuscript left the scriptorium. In the sixth or seventh century many alterations were made, which, according to a colophon at the end of the book of Esdras and Esther states, that the source of these alterations was "a very ancient manuscript that had been corrected by the hand of the holy martyr Pamphylus" (martyred 309 C.E.). If this is so, material which begin with 1 Samuel to the end of Esther is Origen's copy of the Hexapla. From this is concluded, that it had been in Caesarea Maritima in the sixth or seventh centuries.[15] Uncorrected is the pervasive iotacism, especially of the ει diphthong.

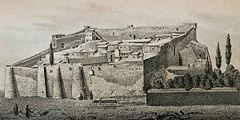

Discovery

The Codex was probably seen in 1761 by the Italian traveller, Vitaliano Donati, when he visited Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai.[16] However, it was not until 1844, when the modern re-discovery of the document was officially made. Credit for this discovery goes to Constantin von Tischendorf who allegedly saw some leaves of parchment in a waste-basket during his first visit to Monastery of Saint Catherine. He claimed the leaves of parchment were relegated as "rubbish which was to be destroyed by burning it in the ovens of the monastery",[17] although this is firmly denied by the Monastery. After examination he realized that they were part of the Septuagint, written in an early Greek uncial script. He retrieved from the basket 129 leaves in Greek which he identified as coming from a manuscript of the Septuagint. He asked if he might keep them, but at this point the attitude of the monks changed, they realized how valuable these old leaves were, and Tischendorf was permitted to take only one-third of the whole, i.e. 43 leaves. These leaves contained portions of 1 Chronicles, Jeremiah, Nehemiah, and Esther. After his return they were deposited in the University Library at Leipzig, where they still remain. In 1846, Tischendorf published their contents, naming them the 'Codex Frederico-Augustanus' (in honor Frederick Augustus).

In 1845, Archimandrite Porphiryj Uspenski (1804-1885), later archbishop of Sinai, visited the monastery and the codex was shown to him, together with leaves which Tischendorf had not seen.

In 1853, Tischendorf revisited the monastery again at Sinai, to get the remaining 86 folios, but without success. Among these folios were all of Isaiah and 1 and 4 Maccabees.[18] The Codex Sinaiticus was shown to Constantin von Tischendorf on his third visit to the Monastery of Saint Catherine, at the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt, in 1859. (However, this story may have been a fabrication, or the manuscripts in question may have been unrelated to Codex Sinaiticus: Rev. J. Silvester Davies in 1863 quoted "a monk of Sinai who… stated that according to the librarian of the monastery the whole of Codex Sinaiticus had been in the library for many years and was marked in the ancient catalogues... Is it likely… that a manuscript known in the library catalogue would have been jettisoned in the rubbish basket." Indeed, it has been noted that the leaves were in "suspiciously good condition" for something found in the trash.)[19] Tischendorf had been sent to search for manuscripts by Russia's Tsar Alexander II, who was convinced there were still manuscripts to be found at the Sinai monastery. The text of this part of the codex was published by Tischendorf in 1862:

- Konstantin von Tischendorf: Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. Leipzig: Giesecke & Devrient, 1862.

It was reprinted in four volumes in 1869:

- Konstantin von Tischendorf, G. Olms (Hrsg.): Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. 1. Prolegomena. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1969 (Repr.).

- Konstantin von Tischendorf, G. Olms (Hrsg.): Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. 2. Veteris Testamenti pars prior. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1969 (Repr.).

- Konstantin von Tischendorf, G. Olms (Hrsg.): Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. 3. Veteris Testamenti pars posterior. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1969 (Repr.).

- Konstantin von Tischendorf, G. Olms (Hrsg.): Bibliorum codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus. 4. Novum Testamentum cum Barnaba et Pastore. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1969 (Repr.).

The complete publication of the codex was made by noted English scholar Kirsopp Lake (1872-1946) in 1911 (New Testament),[20] and in 1922 (Old Testament). It was the full-sized black and white facsimile of the manuscript, made on the basis two earlier facsimiles editing. Lake did not have access to the manuscript.

The story of how von Tischendorf found the manuscript, which contained most of the Old Testament and all of the New Testament, has all the interest of a romance. Von Tischendorf reached the monastery on January 31; but his inquiries appeared to be fruitless. On February 4, he had resolved to return home without having gained his object:

"On the afternoon of this day I was taking a walk with the steward of the convent in the neighbourhood, and as we returned, towards sunset, he begged me to take some refreshment with him in his cell. Scarcely had he entered the room, when, resuming our former subject of conversation, he said: "And I, too, have read a Septuagint"—i.e. a copy of the Greek translation made by the Seventy. And so saying, he took down from the corner of the room a bulky kind of volume, wrapped up in a red cloth, and laid it before me. I unrolled the cover, and discovered, to my great surprise, not only those very fragments which, fifteen years before, I had taken out of the basket, but also other parts of the Old Testament, the New Testament complete, and, in addition, the Epistle of Barnabas and a part of the Shepherd of Hermas.[21]

After some negotiations, he obtained possession of this precious fragment. James Bentley gives an account of how this came about, prefacing it with the comment, "Tischendorf therefore now embarked on the remarkable piece of duplicity which was to occupy him for the next decade, which involved the careful suppression of facts and the systematic denigration of the monks of Mount Sinai."[22] He conveyed it to Tsar Alexander II, who appreciated its importance and had it published as nearly as possible in facsimile, so as to exhibit correctly the ancient handwriting. The Tsar sent the monastery 9000 rubles by way of compensation. Regarding Tischendorf's role in the transfer to Saint Petersburg, there are several views. Although when parts of Genesis and Book of Numbers were later found in the bindings of other books, they were amicably sent to Tischendorf, the codex is currently regarded by the monastery as having been stolen. This view is hotly contested by several scholars in Europe. In a more neutral spirit, New Testament scholar Bruce Metzger writes:

"Certain aspects of the negotiations leading to the transfer of the codex to the Tsar's possession are open to an interpretation that reflects adversely on Tischendorf's candour and good faith with the monks at St. Catherine's. For a recent account intended to exculpate him of blame, see Erhard Lauch's article 'Nichts gegen Tischendorf' in Bekenntnis zur Kirche: Festgabe für Ernst Sommerlath zum 70. Geburtstag (Berlin: c. 1961); for an account that includes a hitherto unknown receipt given by Tischendorf to the authorities at the monastery promising to return the manuscript from Saint Petersburg 'to the Holy Confraternity of Sinai at its earliest request', see Ihor Ševčenko's article 'New Documents on Tischendorf and the Codex Sinaiticus', published in the journal Scriptorium xviii (1964): 55–80.[23]

In September 13, 1862, Constantine Simonides, a forger of manuscripts who had been exposed by Tischendorf, by way of revenge made the claim in print in The Guardian that he had written the codex himself as a young man in 1839.[24] Henry Bradshaw, a scholar, contributed to exposing the frauds of Constantine Simonides, and exposed the absurdity of his claims in a letter to the Guardian (January 26, 1863). Bradshaw showed that the Codex Sinaiticus brought by Tischendorf from the Greek monastery of Mount Sinai was not a modern forgery or written by Simonides. Simonides' "claim was flawed from the beginning".[25]

Later story of codex

For many decades, the Codex was preserved in the Russian National Library. In 1933, the Soviet Union sold the codex to the British Museum[26] for £100,000 raised by public subscription. After coming to Britain, it was examined by T. C. Skeat and H.J.M. Milne using an ultra-violet lamp.[27]

In May 1975, during restoration work, the monks of Saint Catherine's monastery discovered a room beneath the Saint George Chapel which contained many parchment fragments. Among these fragments were twelve complete leaves from the Sinaiticus Old Testament.[28][29]

In June 2005, a team of experts from the UK, Europe, Egypt, Russia and USA undertook a joint project to produce a new digital edition of the manuscript (involving all four holding libraries), and a series of other studies was announced. This will include the use of hyperspectral imaging to photograph the manuscripts to look for hidden information such as erased or faded text.[30] This is to be done in cooperation with the British Library. This project will cost $1m.[31]

More than one quarter of the manuscript was made publicly available online on July 24, 2008.[32] In July 2009, the entire manuscript will be available.[33]

Present location

The codex is now split into four unequal portions: 347 leaves in the British Library in London (199 of the Old Testament, 148 of the New Testament), 12 leaves and 14 fragments in St. Catherine's Monastery of Sinai, 43 leaves in the Leipzig University Library, and fragments of 3 leaves in the Russian National Library in Saint Petersburg.[1]

At the present day, the monastery in Sinai officially considers that the codex was stolen. Visitors in our day have reported that the monks at Saint Catherine's Monastery display the receipt they received from Tischendorf for the Codex, in a frame that hangs upon the wall.[34]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland. The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, transl. Erroll F. Rhodes. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995), 107

- ↑ Robert Bringhurst. (2004). The Elements of Typographic Style (version 3.0). (Vancouver: Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0881792055), 174–175.

- ↑ Codex Sinaiticuscodex-sinaiticus.net. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ Also in Minuscule 69 and several other minuscule manuscripts Pauline epistles precede Acts.

- ↑ The same variant present manuscripts: Magdalen papyrus P67, Minuscule 2174, pc, vg, eth.

- ↑ Gordon D. Fee, "Codex Sinaiticus in the Gospel of John." NTS 15 (1968-1969): 22-44.

- ↑ H.C. Hoskier. Codex B and Its Allies, a Study and an Indictment. (London; 1914), 1.

- ↑ B. F. Westcott and F. J. A. Hort. Introduction to the Study of the Gospels. (1860), 40.

- ↑ The Four Gospels, a Study of Origins treating of the Manuscript Tradition, Sources, Authorship, & Dates, (1924), 590-597. katapi.org. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ H.J.M. Milne, and T.C. Skeat. Scribes and Correctors of Codex Sinaiticus. (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1938).

- ↑ Edward A. Button. An Atlas of Textual Criticism. (Cambridge: 1911), 13.

- ↑ T.C. Skeat, "The Codex Sinaiticus, The Codex Vaticanus and Constantine." Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999): 583-625.

- ↑ I.M. Price. The Ancestry of Our English Bible an Account of Manuscripts, Texts and Versions of the Bible. (Sunday School Times Co, 1923), 146 f.

- ↑ T.C. Skeat, "The Codex Sinaiticus, The Codex Vaticanus and Constantine," Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999): 583-625.

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration. (Oxford University Press, 1992), 46.

- ↑ G. Lumbroso. Atti della R. Accademia dei Lincei. (1879), 501.

- ↑ T. C. Skeat, "The Last Chapter in the History of the Codex Sinaiticus." Novum Testamentum Vol. 42, Fasc. 3, (July 2000): 313

- ↑ K.v. Tischendorf. When Were Our Gospels Written? An Argument by Constantine Tischendorf. With a Narrative of the Discovery of the Sinaitic Manuscript. (New York: American Tract Society, 1866).

- ↑ Davies words are from a letter published in The Guardian on May 27, 1863, as quoted by J.K. Elliott in Codex Sinaiticus and the Simonides Affair. (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1982), 16; Elliott in turn is quoted by Michael D. Peterson in his essay "Tischendorf and the Codex Sinaiticus: the Saga Continues," in The Church and the Library, ed. Papademetriou and Sopko. (Boston: Somerset Hall Press, 2005), 77 ; See also notes 2 and 3, p. 90, in Papademetriou.

- ↑ Kirsopp Lake. Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus: The New Testament, the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911).

- ↑ See Constantin von Tischendorf, The Discovery of the Sinaitic Manuscript, Extract from Constantin von Tischendorf, When Were Our Gospels Written? An Argument by Constantine Tischendorf. With a Narrative of the Discovery of the Sinaitic Manuscript (New York: American Tract Society, 1866).

- ↑ James Bentley, Secrets of Mount Sinai (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1986), 95.

- ↑ Bruce A. Metzger. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption and Restoration. (Oxford University Press, 1992), 45.

- ↑ J.K. Elliott in "Codex Sinaiticus and the Simonides Affair," (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1982), 16.

- ↑ A history of Cambridge University Press. By David McKitterick, Volume 2: Scholarship and Commerce (1698-1872), (369).

- ↑ After 1973 in the British Library.

- ↑ H.J.M. Milne and T.C. Skeat. Scribes and Correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus. (London: The British Museum, 1938)

- ↑ T.C. Skeat, "The Last Chapter in the History of the Codex Sinaiticus," Novum Testamentum XLII, 4: 313-315.

- ↑ Codex Sinaiticus finds 1975 with images taken from the German "Bibelreport" (German Bible Society, 2002). Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ Oldest known Bible to go online. BBC News, August 3, 2005. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ E. Henschke, "Digitizing the Hand-Written Bible: The Codex Sinaiticus, its History and Modern Presentation," Libri vol. 57 (2007): 45-51.

- ↑ Codex Sinaiticus Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ↑ press release The world’s oldest Bible goes online codexsinaiticus. November 19, 2008

- ↑ BBC Radio 4 programme "The Oldest Bible"—only online for a limited period 5/Oct/2008. BBC. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

- Aland, Kurt, and Barbara Aland. The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, transl. Erroll F. Rhodes. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1995.

- Bentley, James. Secrets of Mount Sinai. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1986. ASIN: B000KNEFFS.

- Bringhurst, Robert. 2004. The Elements of Typographic Style (version 3.0). Vancouver: Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0881792055.

- Button, E.A., An Atlas of Textual Criticism. Cambridge: 1911.

- Elliott, J.K., Codex Sinaiticus and the Simonides Affair. Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1982.

- Epp, Eldon J. and Gordon D. Fee. Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1993. ISBN 080282773X.

- Fee, Gordon D., "Codex Sinaiticus in the Gospel of John." NTS 15 (1968-1969)

- Hoskier, H.C., Codex B and Its Allies, a Study and an Indictment. London: 1914.

- Kenyon, F.G. Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts, 4th ed., London: 1939.

- Lake, Kirsopp. Codex Sinaiticus Petropolitanus: The New Testament, the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911.

- Lumbroso, G. Atti della R. Accademia dei Lincei. 1879.

- Magerson, P., "Codex Sinaiticus: An Historical Observation," Bib Arch 46 (1983): 54-56.

- McKitterick, David. A History of Cambridge University Press. (in four volumes) Volume 2: Scholarship and Commerce (1698-1872). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998. ISBN 052130802X.

- Metzger, Bruce M. Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Palaeography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0195029240.

- Metzger, Bruce M. and Bart D. Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0195072979.

- Milne, H.J.M. and T. C. Skeat. Scribes and Correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus. London: British Museum, 1938.

- Peterson, Michael D., "Tischendorf and the Codex Sinaiticus: the Saga Continues," in The Church and the Library: Studies in Honor of Rev. Dr. George C. Papademetriou, ed. by Dean Papademetriou and Andrew J. Sopko. Boston: Somerset Hall Press, 2005. ISBN 0972466118.

- Price, I.M., The Ancestry of Our English Bible an Account of Manuscripts, Texts and Versions of the Bible. Sunday School Times Co, 1923.

- Skeat, T.C., "The Codex Sinaiticus, The Codex Vaticanus and Constantine." Journal of Theological Studies 50 (1999): 583-625.

- Skeat, T.C., "The Last Chapter in the History of the Codex Sinaiticus." Novum Testamentum Vol. 42, Fasc. 3, (July 2000): 313.

- Streeter, B.H. The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins the Manuscripts Tradition, Sources, Authorship, & Dates. Oxford: MacMillan and Co Limited, 1924.

- von Tischendorf, Constantin. When Were Our Gospels Written? An Argument by Constantine Tischendorf. With a Narrative of the Discovery of the Sinaitic Manuscript. New York: American Tract Society, 1866.

- Westcott, B.F., and F. J. A. Hort. Introduction to the Study of the Gospels. 1860.

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- Codex Sinaiticus Project

- Codex Sinaiticus page at bible-researcher.com

- Hershel Shanks, Who Owns the Codex Sinaiticus: How the monks at Mt. Sinai got conned Biblical Archaeology Review Library.

- Roger Bolton, The rival to the Bible, the BBC News magazine.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.