Thomas Aquinas

| Western Philosophers Medieval Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Thomas Aquinas | |

| Birth: c.1225 (Castle of Roccasecca, near Aquino, Italy) | |

| Death: 7 March, 1274 (Fossanova Abbey, Lazio, Italy) | |

| School/tradition: Scholasticism, Founder of Thomism | |

| Main interests | |

| Metaphysics (incl. Theology), Logic, Mind, Epistemology, Ethics, Politics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Five Proofs for God's Existence, Principle of double effect | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Aristotle, Boethius, Eriugena, Anselm, ibn Rushd, ben Maimom, St. Augustine | Giles of Rome, Godfrey of Fontaines, Jacques Maritain, G. E. M. Anscombe, Ayn Rand, Dante |

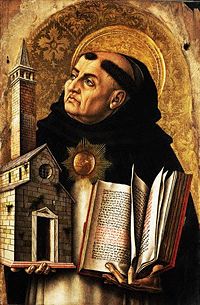

Saint Thomas Aquinas [Thomas of Aquin, or Aquino] (c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Catholic philosopher and theologian in the scholastic tradition, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Universalis. He is the most famous classical proponent of natural theology. He gave birth to the Thomistic school of philosophy, which was long the primary philosophical approach of the Catholic Church. He is considered by the Catholic Church to be its greatest theologian; he is one of the thirty-three Doctors of the Church. Also, many institutions of learning have been named after him.

Biography

Early years of his life

The life of Thomas Aquinas offers many interesting insights into the world of the High Middle Ages. He was born into a family of the south Italian nobility and was through his mother, Countess Theadora of Theate, related to the Hohenstaufen dynasty of Holy Roman emperors.

He was probably born early in 1225 at his father Count Landulf's castle of Roccasecca in the kingdom of Naples (which is today in the Province of Frosinone, belonging to the Regione Lazio). Landulf's brother, Sinibald, was abbot of the original Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino, and the family intended Thomas to follow his uncle into that position; this would have been a normal career-path for a younger son of the nobility.

In his fifth year he was sent for his early education to the monastery. However, after studying for six years at the University of Naples, he left it in his sixteenth year. While there he probably came under the influence of the Dominicans, who were doing their utmost to enlist within their ranks the ablest young scholars of the age, representing along with the Franciscan order a revolutionary challenge to the well-established clerical systems of early medieval Europe.

This change of heart did not please the family; on the way to Rome, Thomas was seized by his brothers and brought back to his parents at the castle of San Giovanni, where he was held a captive for a year or two to make him relinquish his purpose.

According to his earliest biographers, the family even brought a prostitute to tempt him, but he drove her away (allegedly by reaching into the fire and chasing her out of the room with a firebrand, then slamming the door and using the firebrand to mark a cross on the door). Finally, the opposition of his family was overcome by the intervention of Pope Innocent IV, and Thomas assumed the habit of St. Dominic in his seventeenth year.

His superiors, seeing his great aptitude for theological study, sent him to the Dominican school in Cologne, where Albertus Magnus was lecturing on philosophy and theology; he arrived probably in late 1244. He accompanied Albertus to the University of Paris in 1245, and remained there with his teacher for three years, at the end of which he graduated as bachelor of theology. In 1248 he returned to Cologne with Albertus, and was appointed second lecturer and magister studentium. This year may be taken as the beginning of his literary activity and public life. Before he left Paris he had thrown himself with ardour into the controversy raging between the university and the Friar-Preachers respecting the liberty of teaching, resisting both by speeches and pamphlets the authorities of the university; and when the dispute was referred to the pope, the youthful Aquinas was chosen to defend his order, which he did with such success as to overcome the arguments of Guillaume de St Amour, the champion of the university, and one of the most celebrated men of the day.

For several years longer Thomas remained with the famous philosopher of scholasticism, presumably teaching. This long association of Thomas with the great philosopher theologian was the most important influence in his development; it made him a comprehensive scholar and won him permanently for the Aristotelian method.

Career

In 1252 Aquinas went to Paris for his master's degree, but met with some difficulty owing to attacks on the mendicant orders by the professoriate of the University. Ultimately, however, he received the degree and entered upon his office of teaching in 1256, when, along with his friend Bonaventura, he was named doctor of theology and began to give courses of lectures upon this subject in Paris, Rome, and other towns in Italy. From this time onward his life was one of incessant toil; he was continually engaged in the active service of his order, was frequently travelling upon long and tedious journeys, and was constantly consulted on affairs of state by the reigning pontiff.

In 1259 he was present at an important chapter of his order at Valenciennes. At the solicitation of Pope Urban IV (therefore not before the latter part of 1261), he took up his residence in Rome. In 1263 we find him at the chapter of the Dominican order held in London. In 1268 he was lecturing now in Rome and Bologna, all the while engaged in the public business of the church.

During 1269 to 1271 he was again active in Paris, lecturing to the students, managing the affairs of the church and consulted by the king, Louis VIII, his kinsman, on affairs of state. In 1272 the provincial chapter at Florence empowered him to found a new studium generale at such place as he should choose, and the commands of the chief of his order and the request of King Charles brought him back to the professor's chair at Naples.

All this time he was preaching every day, writing homilies, disputations, lectures, and finding time to work hard at his great work the Summa Theologiae. Such rewards as the church could bestow had been offered to him. He refused the archbishopric of Naples and the abbacy of Monte Cassino.

Aquinas had a mystical experience while celebrating Mass on 6 December, 1273, after which he stopped writing, leaving his great work, the Summa Theologiae, unfinished. When asked why he had stopped writing, Aquinas replied, "I cannot go on...All that I have written seems to me like so much straw compared to what I have seen and what has been revealed to me." Other mystical experiences reported include a voice telling him from a cross that he had written well and monks finding him levitating. The 20th century Roman Catholic writer/convert G. K. Chesterton describes these and other stories in his work on Aquinas, The Dumb Ox, a title based on early impressions that Aquinas was not proficient in speech. These impressions were refuted by Albertus Magnus, who declared, "You call him a Dumb Ox; I tell you the Dumb Ox will bellow so loud his bellowing will fill the world."

Contemporaries described Thomas as a big man, corpulent and dark-complexioned, with a large head and receding hairline. His manners showed his breeding; he is described as refined, affable, and lovable. In argument he maintained self-control and won over opponents by his personality and great learning. His tastes were simple. His associates were specially impressed by his power of memory. When absorbed in thought, he often forgot his surroundings. The ideas he developed by such strenuous absorption he was able to express for others systematically, clearly and simply. Because of the keen grasp he had of his materials, in his writings Thomas does not, like Duns Scotus, make the reader his associate in the search for truth, but teaches it authoritatively. On the other hand, the consciousness of the insufficiency of his works in view of the revelation which he believed he had received was a cause of dissatisfaction for him. His father mandated him to be the heir of Aquino, as it had been dictated in the 1238 decree of the Roman Empire. But because of his strong will to be come a friar, he lost the privilege. The documents which prove these are hidden inside the Vatican secret archives; thus, there is little information regarding this event.

Death and canonization

In January 1274 Pope Gregory X directed him to attend the Second Council of Lyons, to investigate and if possible settle the differences between the Greek and Latin churches, and, though far from well, he undertook the journey. On the way he stopped at the castle of a niece and there became seriously ill.

He wished to end his days in a monastery and, not being able to reach a house of the Dominicans, he was taken to the Cistercian monastery of Fossa Nuova (today Fossanova), one mile from Priverno. After a lingering illness of seven weeks, he died on 7 March, 1274.

Dante (Purg. xx. 69) asserts that he was poisoned by order of Charles of Anjou. Villani (ix. 218) quotes the belief, and the Anonimo Fiorentino describes the crime and its motive. But Muratori, reproducing the account given by one of Thomas's friends, gives no hint of foul play.

Aquinas had made a remarkable impression on all who knew him. He was placed on a level with the Saints Paul and Augustine, receiving the title doctor angelicus (Angelic Doctor). In The Divine Comedy Dante sees the glorified spirit of Aquinas in the Heaven of the Sun with the other great exemplars of religious wisdom.

In 1319, the Roman Catholic Church began investigations preliminary to Aquinas's canonization; on 18 July, 1323, he was pronounced a saint by Pope John XXII at Avignon. In 1567 Pius V ranked the festival of St. Thomas with those of the four great Latin fathers: Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory.

At the Council of Trent only two books were placed on the altar: the Bible and Aquinas's Summa Theologiae. No theologian save Augustine has had an equal influence on the theological thought and language of the Western Church, a fact which was strongly emphasized by Leo XIII in his Encyclical of 4 August, 1879, which directed the clergy to take the teachings of Aquinas as the basis of their theological position, stating that his theology was a definitive exposition of Catholic doctrine. Also, Leo XIII decreed that all Catholic seminaries and universities must teach Aquinas's doctrines, and where Aquinas did not speak on a topic, the teachers were "urged to teach conclusions that were reconcilable with his thinking."

In 1880 Aquinas was declared patron of all Roman Catholic educational establishments. In a monastery at Naples, near the cathedral of St. Januarius, a cell is still shown in which he supposedly lived. His feast day is celebrated on 28 January. Since 1974 his remains have rested in the Church of the Jacobins, Toulouse.

Philosophy

The philsophy of Aquinas is "rich and varied."[1] It has had an enormous influence on subsequent Christian theology, especially that of the Roman Catholic Church, and on Western philosophy in general, where he stands as a vehicle and modifier of Aristotelianism. Even atheist philosophers have been strongly influenced by Aquinas. Ayn Rand "always firmly insisted that Aristotle was the greatest [philosopher] and that Thomas Aquinas was the second greatest."[2]

Philosophically, Aquinas's most important and enduring work is his systematic theology: Summa Theologiae.

Epistemology

Revelation

Aquinas believed in two types of revelation from God: general revelation and special revelation.[3] The former was defined as Nature, the creation. Though one could know the existence of God and some of his attributes through natural revelation, certain specifics can only be known through special revelation, which, to Aquinas, meant the Bible. The Trinity and the Incarnation, in short, the Christian religion, were disclosed to humans in scriptures and could not have been known otherwise. Special revelation, however, does not contradict natural revelation.[4]

Analogy

An important element in Aquinas's philosophy is his theory of analogy. Aquinas noted three different forms of descriptive language: univocal, analogical, and equivocal.[5] Univocality is the use of a descriptor in the same sense when applied to two objects. Equivocation is the complete change in meaning of the descriptor and is a logical fallacy. Analogy, Aquinas maintained, occurs when a descriptor changes some of its meaning, but maintains some as well. It is necessary when talking about God, the Necessary Being. Some of the aspects of the divine nature are hidden (Deus absconditus) and others revealed (Deus revelatus) to finite human minds. To Aquinas, only through analogical language can we describe God. We can know about God through his creation (natural revelation), but only analogically. We can speak only of God's goodness by understanding that goodness as applied to humans and to God are similar, not identical (but neither absolutely different). This led Aquinas to postulate a via negativa, or negative way, though which we must negate all limited aspects of goodness which we understand in applying the term to humans when we apply it to God: we must remove potentiality from it, we must apply only the "perfection signified" and not the "finite mode of signification."[6]

Quinquae viae

Aquinas's Five Ways perhaps the most famous feature of his whole corpus of philosophical writings, continue to be well-used as some of the most well-known and influential theistic proofs formulated. Aquinas's arguments are mostly cosmological in nature.[7]

- Motion proves the existence of an Unmoved Mover.[8]

- Effects proves the existence of a First Cause.[9]

- Contingency proves the existence of a Necessary Being.[10]

- Degrees of perfection prove the existence of a Most Perfect Being.[11]

- Design proves the existence of a Designer.[12] (This argument is teleological in nature.)

Ethics

Aquinas's ethics is based on the concept of "first principles of action."[13] In his Summa Theologiae, he wrote:

- Virtue denotes a certain perfection of a power. Now a thing's perfection is considered chiefly in regard to its end. But the end of power is act. Wherefore power is said to be perfect, according as it is determinate to its act.[1]

Aquinas defines the four cardinal virtues as prudence, temperance, justice, and courage. The cardinal virtues are natural and revealed in Nature and binding on all.[14] There are, however, theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. These are supernatural and they are distinct from other virtues in their object, namely God:

- Now the object of the theological virtues is God Himself, Who is the last end of all, as surpassing the knowledge of our reason. On the other hand, the object of the intellectual and moral virtues is something comprehensible to human reason. Wherefore the theological virtues are specifically distinct from the moral and intellectual virtues.[2]

Aquinas, furthermore, distinguished four kinds of law.[15] These are the eternal, natural, human, and divine law. The first is the decree of God which governs all creation. The second is the human "participation" in the eternal law. Herein lies Aquinas great contribution to natural law theory. Natural law is discoverred by reason[16] As stated above, it is based on "first principles":

- . . . this is the first precept of the law, that good is to be done and promoted, and evil is to be avoided. All other precepts of the natural law are based on this . . .[3]

The desire to live and to procreate are counted by Aquinas among those basic (natural) human values on which all human values are based.[17] Human law is positive law: the natural law applied by governments to societies. Divine law is the specially revealed law in the Scriptures.

Aquinas is also important as an influence on the Roman Catholic church for his contribution to the theology of mortal and venial sins.

Modern criticism

Some of Aquinas's ethical conclusions are at odds with the majority view in the contemporary West. For example, he held that heretics "deserve not only to be separated from the Church by excommunication, but also to be severed from the world by death," and thus that heresy should be punished by death (ST II:II 11:3). He also maintained woman's subjection to man on account of her intellectual inferiority (ST I:92:1), which is one reason why he opposed the ordination of women (ST Supp. 39:1). Aquinas did say, however, that women were fit for the exercise of temporal power. He also held that "a parent can lawfully strike his child, and a master his slave that instruction may be enforced by correction" (ST II:II 65:2).

On the other hand, many modern ethicists (notably Philippa Foot and Alasdair MacIntyre), both within and outside of the Catholic Church, have recently become very excited about Aquinas's virtue ethics as a way of avoiding utilitarianism or Kantian deontology. Through the work of 20th century philosophers such as Roman Catholic convert Elizabeth Anscombe (especially in her book Intention), Aquinas's principle of double effect specifically and his theory of intentional activity generally have been influential.

Modern readers might also find the method frequently used to reconcile Christian and Aristotelian doctrine rather strenuous. In some cases, the conflict is resolved by showing that a certain term actually has two meanings: the Christian doctrine referring to one meaning, the Aristotelian to the second. Thus, both doctrines can be said to be true. Indeed, noting distinctions is a necessary part of true philosophical inquiry. In most cases, Aquinas finds a reading of the Aristotelian text which might not always satisfy modern scholars of Aristotle but which is a plausible rendering of the Philosopher's meaning and is thoroughly Christian.

It is remarkable that Aquinas's aesthetic theories, especially the concept of claritas, deeply influenced the literary practice of modernist writer James Joyce, who used to extol Aquinas as the greatest Western philosopher. The influence of Aquinas's aesthetics can be also found in the works of the Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, who wrote an essay on aesthetic ideas in Aquinas (published in 1956 and republished in 1988 in a revised edition).

Many biographies of Aquinas have been written over the centuries, one of the most notable by G.K. Chesterton.

Editions

The best modern edition of the works of Aquinas is that prepared at the expense of Leo XIII. (Rome, 1882-1903). The Abbé Migne published a very useful edition of the Summa Theologiae, in four 8vo vols., as an appendix to his Patrologiae Cursus Completus; English editions, J. Rickaby (London, 1872), J. M. Ashley (London, 1888).

Notes

- ↑ Geisler, Norman L. (ed). Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics. Baker Academic: Grand Rapids, MI, 1999. p. 725.

- ↑ Long, Roderick T. "Ayn Rand's contribution to the cause of freedom." (2006-03-23)..

- ↑ Geisler, p. 725.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Sproul, R. C. Renewing Your Mind. Baker Books: Grand Rapids, MI, 1998. p. 33.

- ↑ Geisler, p. 726.

- ↑ Geisler, p. 725.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Geisler, p. 727.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Pojman, Louis P. Ethics. Wadsworth Publishing Co.: Belmont, CA, 1995.

- ↑ Ibid.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "Bibliography of Additional Readings" (1990). In Mortimer J. Adler (Ed.), Great Books of the Western World, 2nd ed., v. 2, pp. 987-988. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Craig Paterson & Matthew S. Pugh (eds.) Analytical Thomism: Traditions in Dialogue. Ashgate, 2006.

See also

| Saints Portal |

- Works by Thomas Aquinas

- Institutions named after Thomas Aquinas

- Thomism

- School of Salamanca, 16th century Spanish Thomists

- Bartholomew of Lucca, Aquinas' friend and confessor

- Etienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain, 20th-century Thomists

External links

By Aquinas

- Summa contra Gentiles

- Summa Theologiae

- The Principles of Nature

- On Being and Essence (De Ente et Essentia)

- Catena Aurea (partial)

- Corpus Thomisticum - the works of St. Thomas Aquinas (Latin)

- Works by Thomas Aquinas. Project Gutenberg

About Aquinas

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Article on Thomism by the Jacques Maritain Center of Notre Dame University [4]

- Biography of Aquinas by G. K. Chesterton (Warning: protected by copyright outside of Australia)

- On the legend of St. Albert's automaton

- Aquinas on Intelligent Extra-Terrestrial Life

- St Thomas of Aquinas Selected Prayers and poems

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- [5] bio and ideas at SWIF/University of Bari/Italy

- Aquinas' Moral, Political and Legal Philosophy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.