Sioux

| Sioux |

|---|

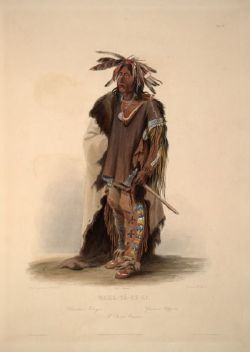

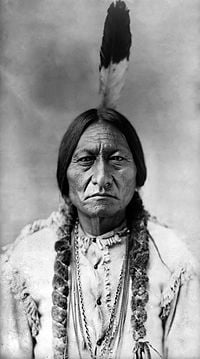

Photograph of Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota chief and holy man, circa 1885 |

| Total population |

| 150,000+[1][2] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States of America (SD, MN, NE, MT, ND), Canada (MB, SK, AB) |

| Languages |

| English, Sioux |

| Religions |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), Midewiwin |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Assiniboine, Stoney (Nakoda), and other Siouan peoples |

The Sioux (IPA /su/) are a Native American and First Nations people. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or any of the nation's many dialects. The Sioux comprise three major divisions based on dialect and subculture:

- Teton (“Dwellers on the Prairie”): the westernmost Sioux, known for their hunting and warrior culture, and are often referred to as the Lakota.

- Isanti ("Knife," originating from the name of a lake in present-day Minnesota): residing in the extreme east of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and northern Iowa, and are often referred to as the Santee or Dakota.

- Ihanktowan-Ihanktowana ("Village-at-the-end" and "little village-at-the-end"): residing in the Minnesota River area, they are considered to be the middle Sioux, and are often referred to as the Yankton-Yanktonai or Nakota.

Today, the Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and also in Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada.

Oceti Sakowin

Today it is preferable to refer to the Teton, Isanti, or Ihanktowan/Ihanktowana as either Lakota, Dakota, or Nakota respectively.[3] In any of the three main dialects, "Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota" all translate to mean "friend," or more properly, "ally." Usage of Lakota, Dakota, or Nakota may then refer to the alliance that once bound the Great Sioux Nation together. The historical Sioux referred to the Great Sioux Nation as the Oceti Sakowin, meaning "Seven Council Fires." Each fire represented a tiyospaye (family or band). The seven nations that comprise the Sioux are: Mdewakanton, Wahpetowan (Wahpeton), Wahpekute, Sissetowan (Sisseton), the Ihantowan (Yankton), Ihanktowana (Yanktonai), and the Teton (Lakota).[3]

Historically, the Seven Council Fires would assemble each summer to hold council, renew kinships, decide tribal matters and hold the Sun Dance.[4] The seven divisions would select four leaders known as Wicasa Yatapicka from among the leaders of each division.[4] Being one of the four leaders was considered the highest honor for a leader; however, the once-a-year gathering meant the majority of tribal administration was cared for by the usual leaders of each division. The last meeting of the seven council fires was in 1850.[4]

Political organization

The historical political organization was based on the participation of individuals and the cooperation of many to sustain the tribe’s way of life. Leadership was chosen from noble birth and through demonstrations of bravery, fortitude, generosity, and wisdom.[4]

Societies

The leadership positions were usually hereditary with future leaders being chosen by their war record and generosity. Tribal leaders were members of the Naca Ominicia society and decided matters of tribal hunts, camp movements, whether to make war or peace with their neighbors, or any other community action.[5] Societies were similar to fraternities, whereas the men joined to raise their position in the tribe. Societies were composed of smaller clans and varied in number among the seven divisions.[4] There were two types of societies: Akicita, for the younger men, and Naca, for elders and former leaders.[4]

Akicita societies

Akicita societies put their efforts into training men as warriors, participating in tribal hunts, policing, and upholding civility among the community.[5] There were many smaller Akicita societies, including the Kit-Fox, Strong Heart, Elk, and so on.[5]

Naca societies

Leaders in the Naca societies, per Naca Ominicia, were the tribal elders and leaders, who would elect seven to ten men, depending on the division, called Wicasa Itacans. The Wicasa Itacans interpreted and enforced the decisions of the Naca.[5]

The Wicasa Itacans would elect two to four Shirt Wearers who were the voice of the Wicasa. Concerned with the welfare of the nation, they could settle quarrels among families or with foreign nations, among their responsibilities.[4] Shirt Wearers were generally elected from highly respected sons of the leaders; however, men with obscure parents who displayed outstanding leaderships skills and had earned the respect of the community could be elected, exemplified by Crazy Horse.[4]

Under the Shirt Wearers were the Wakincuza, or Pipe Holders. They held a prominent position during peace ceremonies, regulated camp locations, and supervised the Akicita societies during buffalo hunts.[5]

)

)

Name origins

The name "Sioux" is an abbreviated form of Nadouessioux borrowed into French Canadian from Nadoüessioüak from the early Ottawa exonym: na•towe•ssiwak "Sioux." It was first used by Jean Nicolet in 1640.[3] The Proto-Algonquian form *nātowēwa meaning "Northern Iroquoian" has reflexes in several daughter languages that refer to a small rattlesnake (massasauga, Sistrurus).[6] This information was interpreted by some that the Ottawa borrowing was an insult. However, this proto-Algonquian term most likely is ultimately derived from a form *-ātowē meaning simply "speak foreign language," which was later extended in meaning in some Algonquian languages to refer to the massasauga. Thus, contrary to many accounts, the Ottawa word na·towe·ssiwak never equated the Sioux with snakes. This is not confirmed though, as usage over the previous decades has led to this term having negative connotations to those tribes to which it refers. This would explain why many tribes have rejected this term when referring to themselves.

Some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sicangu Oyate, and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternative English spelling of Ogallala is considered improper).[3]

Linguistics

The earlier linguistic 3-way division of the Dakotan branch of the Siouan family identified Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota as dialects of a single language, where Lakota = Teton, Dakota = Santee and Yankton, Nakota = Yanktonai & Assiniboine. This classification was based in large part on each group's particular pronunciation of the autonym Dakhóta-Lakhóta-Nakhóta, meaning the Yankton-Yanktonai, Santee, and Teton groups all spoke mutually intelligible varieties of a Sioux idiom.[6] However, more recent study identifies Assiniboine and Stoney as two separate languages with Sioux being the third language that has three similar dialects: Teton, Santee-Sisseton, Yankton-Yanktonai. Furthermore, the Yankton-Yanktonai never referred to themselves using the pronunciation Nakhóta but rather pronounced it the same as the Santee (i.e. Dakhóta). (Assiniboine and Stoney speakers use the pronunciation Nakhóta or Nakhóda).

The term Dakota has also been applied by anthropologists and governmental departments to refer to all Sioux groups, resulting in names such as Teton Dakota, Santee Dakota, etc. This was due in large part to the misrepresented translation of the Ottawa word from which Sioux is derived (supposedly meaning "snake," see above).[4]

Modern geographic divisions

The Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and also in Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Sioux was in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.[6] Furthermore, after the introduction of the horse, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land—from present day Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Black Hills and the Powder River country.[5]

Yankton-Yanktonai (Nakota)

The Ihanktowan-Ihanktowana, or the Yankton ("campers at the end") and Yanktonai ("lesser campers at the end") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the lower Yanktonai (Hunkpatina).[6]

Economically, they were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 1700s, they were recorded as living in the Mankato region of Minnesota.[7]

Santee (Dakota)

The Santee people migrated north and westward from the south and east into Ohio then to Minnesota. The Santee were a woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and subsistence farming. Migrations of Anishinaabe/Chippewa people from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Santee further into Minnesota and west and southward, giving the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi and up to its headwaters.[6]

Teton (Lakota)

The western Santee obtained horses, probably in the 17th century (although some historians date the arrival of horses in South Dakota to 1720), and moved further west, onto the Great Plains, becoming the Titonwan tribe, subsisting on the buffalo herds and corn-trade with their linguistic cousins, the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Missouri.[6]

Ethnic divisions

The Sioux are divided into ethnic groups, the larger of which are divided into sub-groups, and further branched into bands. The Yankton-Yanktonai, the smallest division, reside on the Yankton reservation in South Dakota and the Northern portion of Standing Rock Reservation, while the Santee live mostly in Minnesota and Nebraska, but include bands in the Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Crow Creek Reservations in South Dakota. The Lakota are the westernmost of the three groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota.

- Santee division (Dakota)

- Mdewakantonwan ("Dwellers of Spirit Lake")

- notable persons: Taoyateduta

- Sisitonwan (Sisseton, "Dwellers of the Fish Grounds")

- Wahpekute ("Leaf Shooters")

- notable persons: Inkpaduta

- Wahpetonwan ("Dwellers among the Leaves")

- Mdewakantonwan ("Dwellers of Spirit Lake")

- Yankton-Yanktonai division (Nakota)

- Ihanktonwan (Yankton, "End Village")

- Ihanktonwana (Yanktonai, "Little End Village")

- notable persons: Wanata

- Stoney (Canada)

- Assiniboine (Canada)

- Titonwan/Teton division (Lakota) ("Dwellers on the Prairie")

- Oglala ("Those who Scatter their own")

- notable persons: Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, Black Elk and Billy Mills (Olympian)

- Hunkpapa (meaning "Those who Camp by the Door" or "Wanderers")

- notable persons: Sitting Bull

- Sihasapa (not to confuse with the Algonquian-speaking Blackfeet)

- Minniconjou ("Those who Plant by the Stream")

- notable persons: Lone Horn, Touch the Clouds

- Sićangu (French: Brulé) ("Burnt Thighs")

- Itazipacola (French: Sans Arcs "Without Bows")

- Oohenonpa ("Two Kettles" or "Two Boilings")

- Oglala ("Those who Scatter their own")

Reserves and First Nations

Today, one half of all enrolled Sioux in the United States live off the reservation. Also, to be an enrolled member in any of the Sioux tribes in the United States, 1/4 degree is require.[8]

In Canada, the Canadian goverment recognizes reserves as "First Nations."

| Reserve | Bands residing | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Fort Peck Indian Reservation | Lower Yanktonai, Wahpekute, Sisseton, Wahpeton | Montana, USA |

| Spirit Lake Reservation

(Formerly Devil's Lake Reservation) |

Wahpeton, Sisseton, Upper Yanktonai | North Dakota, USA |

| Standing Rock Indian Reservation | Upper Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfoot | North Dakota, South Dakota USA |

| Lake Traverse Indian Reservation | Sisseton, Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Flandreau Indian Reservation | Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Cheyenne River Indian Reservation | Minneconjou, Blackfoot, Two Kettle, Sans Arc | South Dakota, USA |

| Crow Creek Indian Reservation | Lower Yanktonai | South Dakota, USA |

| Lower Brule Indian Reservation | Brulé | South Dakota, USA |

| Yankton Sioux Indian Reservation | Yankton | South Dakota, USA |

| Pine Ridge Indian Reservation | Oglala, few Brulé | South Dakota, USA |

| Rosebud Indian Reservation | Sićangu, few Oglala | South Dakota, USA |

| Upper Sioux Indian Reservation | Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton | Minnesota, USA |

| Lower Sioux Indian Reservation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Shakopee-Mdewakanton Indian Reservation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Prairie Island Indian Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Santee Indian Reservation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Nebraska, USA |

| Sioux Valley First Nation | Sisseton, Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute | Manitoba, Canada |

| Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Sioux Village | Wahpeton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Birdtail Sioux First Nation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Canupawakpa Dakota Nation | Wahpekute, Wahpeton, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation | Sisseton, Wahpeton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Whitecap Dakota First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation | Wahpeton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Wood Mountain | Hunkpapa | Saskatchewan, Canada |

Contact between Sioux and European peoples

Alliance with French fur merchants

Late in the 17th century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants,[9] who were trying to gain advantage in the struggle for the North American fur trade against the English, who had recently established the Hudson's Bay Company. The Dakota were thus lured into the European economic system and the bloody inter-aboriginal warfare that stemmed from it.

Dakota War of 1862

When 1862 arrived shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and one trader, Andrew Myrick, went so far as to tell them that they were 'free to eat grass or their own dung'. As a result, on August 17, 1862 the Dakota War of 1862 began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family, igniting further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. The Santee then attacked the trading post, and Myrick was later found among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass.[10]

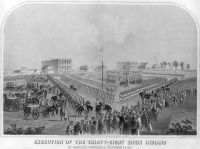

On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in courts-martial, 303 Santee Sioux were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of Caucasian and European farmers and were sentenced to a hanging. No attorneys or witness were allowed as a defense for the accused, and many were convicted in less than five minutes of court time with the judge.[11] President Abraham Lincoln remanded the death sentence of 284 of the warriors, signing off on the execution of 38 Santee men by hanging on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota, the largest mass-execution in US history.[12]

Afterwards, annuities to the Dakota were suspended for four years and the monies were awarded to the white victims. The men who were pardoned by President Lincoln were sent to a prison in Iowa, where more than half died while imprisoned.[11]

Aftermath of Dakota War

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota to Canada, or setted in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri.[11] A few joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military.[11]

Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the 21st century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some ended up eventually in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Tribe today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri. Those who fled to Canada now have descendants residing on eight small Dakota Reserves, four of which are located in Manitoba (Sioux Valley, Long Plain [Dakota Tipi], Birdtail Creek, and Oak Lake [Pipestone]) and the remaining four (Standing Buffalo, Moose Woods [White Cap], Round Plain [Wahpeton], and Wood Mountain) in Saskatchewan.

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War) was an armed conflict between the Sioux and the United States in the Wyoming Territory and the Montana Territory from 1866 to 1868. The war was fought over control of the Powder River Country in north central Wyoming, which lay along the Bozeman Trail, a primary access route to the Montana gold fields.

The war is named after Red Cloud, a prominent chief of Oglala Sioux who led the war against the United States following encroachment into the area by the U.S. military. The war, which ended with the Treaty of Fort Laramie, resulted in a complete victory for the Sioux and the temporary preservation of their control of the Powder River country.[13]

Black Hills War

Between 1876 and 1877, the Black Hills War took place. The Lakota and their allies fought against the United States military in a series of conflicts. The earliest being the Battle of Powder River, and the final battle being at Wolf Mountain. Included are the Battle of the Rosebud, Battle of the Little Bighorn, Battle of Warbonnet Creek, Battle of Slim Buttes, Battle of Cedar Creek, and the Dull Knife Fight.

Wounded Knee Massacre

The Battle at Wounded Knee Creek was the last major armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States, subsequently described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.[14]

On December 29, 1890, five hundred troops of the U.S. 7th Cavalry, supported by four Hotchkiss guns (a lightweight artillery piece capable of rapid fire), surrounded an encampment of the Lakota bands of the Miniconjou and Hunkpapa [15] with orders to escort them to the railroad for transport to Omaha, Nebraska.

By the time it was over, 25 troopers and more than 150 Lakota Sioux lay dead, including men, women, and children. Some of the soldiers are believed to have been the victims of "friendly fire" as the shooting took place at point blank range in chaotic conditions.[16] Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, many of whom may have died from hypothermia.

Usage of the Ghost Dance reportedly insigated the massacre.

Forced relocation

Later in the 19th century, as the railroads hired hunters to exterminate the buffalo herds, their primary food supply, in order to force all tribes into sedentary habitations,[citation needed] the Santee and Lakota were forced to accept white-defined reservations in exchange for the rest of their lands, and domestic cattle and corn in exchange for buffalo, becoming dependent upon annual federal payments guaranteed by treaty. In Minnesota, the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota in 1851 left the Sioux with a reservation twenty miles (32 km) wide on each side of the Minnesota River.

Derived names

The U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota are named after the Dakota tribe. One other U.S. state has a name of Siouan origin: Minnesota is named from mni ("water") plus sota ("hazy/smoky, not clear"), and the name Nebraska comes from the related Chiwere language. Furthermore, the states Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri are named for cousin Siouan tribes, the Kansa, Iowa, and Missouri, respectively, as are the cities Omaha, Nebraska and Ponca City, Oklahoma. The names vividly demonstrate the wide dispersion of the Siouan peoples across the Midwest U.S.

More directly, several Midwestern municipalities utilize Sioux in their names, including Sioux City, Iowa, Sioux Center, Iowa, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Midwestern rivers include the Little Sioux River in Iowa and Big Sioux River along the Iowa/South Dakota border.

Many smaller towns and geographic features in the Northern Plains retain their Sioux names or English translations of those names, including Wasta, Owanka, Oacoma, Rapid City (Mne luza: "cataract" or "rapids"), Sioux Falls/Minnehaha County (Mne haha: "waterfall"), Belle Fourche (Mniwasta, or "Good water"), Inyan Kara, Sisseton (Sissetowan: tribal name), Winona ("first daughter"), etc.

Frontwoman Siouxsie Sioux of the postpunk band Siouxsie and the Banshees also derived her stage name from the "Sioux."

The University of North Dakota's athletic team is known as the "Fighting Sioux." While there is a local desire to retain the historic name, numerous Sioux tribes have issued resolutions asking the University to abolish it.[17][18]

Media

|

|

- The HBO movie Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee depicts the relocations and reservations from the Sioux perspective.

- The films Dances with Wolves and Thunderheart contain depictions of the Sioux People.

- "Elegy to the Sioux," a poem by Norman Dubie

Famous Sioux

Historical

- Taoyateduta (Little Crow)—Chief famous for role in the Dakota War of 1862

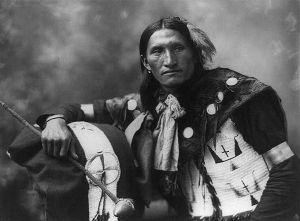

- Tatanka Iyotanke (Sitting Bull)—Chief famous for role in the Battle of Little Bighorn

- Makhpiya-luta (Red Cloud)—Chief famous for role in Red Cloud's War

- Tasunka Witko (Crazy Horse)—Famous for leadership and courage in battle

- Hehaka Sapa (Black Elk)—Lakota holy man, source of Black Elk Speaks and other books

- Tahca Ushte (Lame Deer)—Lakota holy man, carried traditional knowledge into modern era

- Charles Eastman—Author, physician and reformer

- Colonel Gregory "Pappy" Boyington—World War II Fighter Ace and Medal of Honor recipient; 1/4 Sioux

Contemporary

- Robert "Tree" Cody, Native American flutist (Dakota)

- Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, activist, academic, and writer

- Mary Crow Dog, writer and activist

- Vine Deloria, Jr., activist and essayist

- Indigenous, blues band (Nakota)

- Illinois Jacquet, jazz saxophonist (half Sioux and half African American)

- Russell Means, activist (Oglala)

- Ed McGaa, author, (Oglala) CPT US Marine Corp F-4 Phantom Fighter Pilot

- Eddie Spears, actor (Lakota Sioux Lower Brule)

- Michael Spears, actor (Lakota Sioux Lower Brule)

- John Trudell, actor

- Floyd Red Crow Westerman, singer and actor (Dakota)

- Leonard Peltier, imprisoned for allegedly killing two FBI agents in 1975

Lakota

The Lakota (IPA: [laˈkˣota]) (also Lakhota, Teton, Titonwon) are a Native American tribe. They form one of a group of seven tribes (the Great Sioux Nation) and speak Lakota, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language.

The Lakota are the westernmost of the three Sioux groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota. The seven branches or "sub-tribes" of the Lakota are Brulé, Oglala, Sans Arcs, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Sihasapa and Two Kettles.

History

The Lakota are closely related to the western Dakota of Minnesota. After their adoption of the horse, šųká-wakhą́ ([ˈʃũka waˈkˣã]) ('dog [of] power/mystery/wonder') in the early 18th century, the Lakota became part of the Great Plains culture with their eventual Algonkin-speaking allies, the Tsitsistas (Northern Cheyenne), living in the northern Great Plains. Their society centered on the buffalo hunt with the horse. There were 20,000 Lakota in the mid-18th century. The number has now increased to about 70,000, of whom about 20,500 still speak the Lakota language.

After 1720, the Lakota branch of the Seven Council Fires split into two elements, the Saone who moved to the Lake Traverse area on the South Dakota-North Dakota-Minnesota border, and the Oglala-Brulé who occupied the James River Valley. By about 1750, however, the Saone had moved to the east bank of the Missouri, followed 10 years later by the Oglala and Brulé (Sičangu).

The large and powerful Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa villages had prevented the Lakota from crossing the Missouri for an extended period, but when smallpox and other diseases nearly destroyed these tribes, the way was open for the first Lakota to cross the Missouri into the drier, short-grass prairies of the High Plains. These Saone, well-mounted and increasingly confident, spread out quickly. In 1765, a Saone exploring and raiding party led by Chief Standing Bear discovered the Black Hills (which they called the Paha Sapa). Just a decade later, in 1775, the Oglala and Brulé also crossed the river, following the great smallpox epidemic of 1772–1780, which destroyed three-quarters of the Missouri Valley populations. In 1776, they defeated the Cheyenne as the Cheyenne had earlier defeated the Kiowa, and gained control of the land which became the center of the Lakota universe.

Initial contacts between the Lakota and the United States, during the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–06, were friendly. But as more and more settlers crossed Lakota lands, this changed. Formally, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 acknowledged native soverignty over the Great Plains in exchange for free passage along the Oregon Trail, for "as long as the river flows and the eagle flies." In Nebraska on September 3, 1855, 700 soldiers under American General William S. Harney avenged the "Grattan Massacre" by attacking a Lakota village, killing 100 men, women, and children. Other wars followed; and in 1862–1864, as refugees from the "Dakota War of 1862" in Minnesota fled west to their allies in Montana and Dakota Territory, the war followed them. General William Tecumseh Sherman called for genocide in 1867, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the [Lakota], even to their extermination, men, women and children."[19]

Because the Black Hills are sacred to the Lakota, they objected to mining in the area, which had been attempted since the early years of the 19th century. In 1868, the US government signed the Fort Laramie Treaty, exempting the Black Hills from all white settlement forever. 'Forever' lasted only four years, as gold was publicly discovered there, and an influx of prospectors descended upon the area, abetted by army commanders like Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer. The latter tried to administer a lesson of noninterference with white policies, resulting in the Black Hills War of 1876–77. Hunting and massacre of the buffalo were urged by General Philip Sheridan as a means to "destroying the Indians' commissary"[20]

The Lakota with their allies, the Arapaho and the Northern Cheyenne, defeated General George Crook's army at the Battle of the Rosebud and a week later defeated the U.S. 7th Cavalry in 1876 at the Battle at the Greasy Grass or Little Big Horn, killing 258 soldiers and inflicting more than 50% casualties on the regiment. But like the Zulu triumph over the British at Isandlwana in Africa three years later, it proved to be a pyrrhic victory. The Teton were defeated in a series of subsequent battles by the reinforced U.S. Army, and were herded back onto reservations, prevented from hunting buffalo and forced to accept government food distribution, which went to 'friendlies' only.

The Lakota were compelled to sign a treaty in 1877 ceding the Black Hills to the United States, but a low-intensity war continued, culminating, fourteen years later, in the killing of Sitting Bull (December 15, 1890) at Standing Rock and the Massacre of Wounded Knee (December 29, 1890) at Pine Ridge.

Today, the Lakota are found mostly in the five reservations of western South Dakota: Rosebud (home of the Upper Sičangu or Brulé), Pine Ridge (home of the Oglala), Lower Brulé (home of the Lower Sičangu), Cheyenne River (home of several other of the seven Lakota bands, including the Sihasapa and Hunkpapa), and Standing Rock, also home to people from many bands. But Lakota are also found far to the north in the Fort Peck Reservation of Montana, the Fort Berthold Reservation of northwestern North Dakota, and several small reserves in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where their ancestors fled to "Grandmother's [i.e. Queen Victoria's] Land" (Canada) during the Minnesota or Black Hills War.

Large numbers of Lakota also live in Rapid City and other towns in the Black Hills, and in Metro Denver. Lakota elders joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) seeking protection and recognition for their cultural and land rights.

The Lakota name now joins Sioux, Kiowa, Apache, Dakota, Cherokee and other American Indian names that have been given to aircraft. The UH-145 has been selected as the United States Army's new Light Utility Helicopter, and has been named the Lakota.

Ethnonyms

The name Lakota comes from the Lakota autonym, lakhóta "feeling affection, friendly, united, allied." The early French literature does not distinguish a separate Teton division, instead lumping them into a "Sioux of the West" group with other Santee and Yankton bands.

The names Teton and Tintowan comes from the Lakota name thíthųwą (the meaning of which is obscure). This term was used to refer to the Lakota by non-Lakota Sioux groups. Other derivations include: Ti tanka, Tintonyanyan, Titon, Tintonha, Thintohas, Tinthenha, Tinton, Thuntotas, Tintones, Tintoner, Tintinhos, Ten-ton-ha, Thinthonha, Tinthonha, Tentouha, Tintonwans, Tindaw, Tinthow, Atintons, Anthontans, Atentons, Atintans, Atrutons, Titoba, Tetongues, Teton Sioux, Teeton, Ti toan, Teetwawn, Teetwans, Ti-t’-wawn, Ti-twans, Tit’wan, Tetans, Tieton, Teetonwan, etc.

As noted above, the early French sources call the Lakota Sioux with an additional modifier, such as Scioux of the West, West Schious, Sioux des prairies, Sioux occidentaux, Sioux of the Meadows, Nadooessis of the Plains, Prairie Indians, Sioux of the Plain, Maskoutens-Nadouessians, Mascouteins Nadouessi, and Sioux nomades.

Today many of the tribes continue to officially call themselves Sioux which the Federal Government of the United States applied to all Dakota/Lakota/Nakota people in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the Sičangu Oyate (Brulé Nation), and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternate English spelling of Ogallala is deprecated, even though it is closer to the correct pronunciation.) The Lakota have names for their own subdivisions.

Notable persons include Sitting Bull (Tatanka Iyotake) from the Hunkpapa band and Crazy Horse (Tašunka Witko), Red Cloud (Maĥpiya Luta), Black Elk (Hehaka Sapa) and Billy Mills from the Oglala band.

Reservations

Today, one half of all Enrolled Sioux live off the Reservation.

Lakota reservations recognized by the US government include:

- Oglala (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation)

- Brulé (Rosebud Indian Reservation)

- Hunkpapa (Standing Rock Reservation)

- Miniconjou (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Sans Arcs (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Siha Sapa (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

- Two Kettles (Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation)

Some Lakota also live on other Sioux reservations in eastern South Dakota, Minnesota, and Nebraska:

- Santee, in Nebraska

- Crow Creek in Central South Dakota

- Yankton in Central South Dakota

- Flandreau in Eastern South Dakota

- Sisseton-Wahpehton in Northeastern South Dakota and Southeastern North Dakota

- Lower Sioux in Minnesota

- Upper Sioux in Minnesota

- Shakopee in Minnesota

- Prairie Island in Minnesota

In addition several Lakota live on Wood Mountain Indian Reserve often Wood Mountain First Nation northwest of Wood Mountain Post now a Saskatchewan historic site.

Notes

- ↑ United States Census Data. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ Ethnologue Report for Lakota. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Johnson, Michael (2000). The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Osprey Publishing Oxford. ISBN 185532878X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Hassrick, Royal B. and Dorothy Maxwell, Cile M. Bach (1964). The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0607-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Mails, Thomas E. (1973). Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. Prentice-Hall, Inc.. ISBN 013-217216-X.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Riggs, Stephen R. (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Washington Government Printing Office, Ross & Haines, Inc.. ISBN 0-87018-052-5.

- ↑ OneRoad, Amos E. and Alanson Skinner (2003). Begin Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-453-X.

- ↑ Enrollment Ordinance. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ↑ van Houten, Gerry (1991). Corporate Canada An Historical Outline. Progress Books, 6-7.

- ↑ Mark, Steil; Tim Post, "m/part2.shtml Let them eat grass", Minnesota Public Radio, 2002-09-26. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Time-Life Books (1994). War for the Plains. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-9445-0.

- ↑ Mark, Steil; Tim Post, "m/part5.shtml Execution and expulsion", Minnesota Public Radio, 2002-09-26. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ *Brown, Dee (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, ch. 6. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-5531-1979-6.

- ↑ Letter: General Nelson A. Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 13, 1917.

- ↑ Liggett, Lorie (1998). Wounded Knee Massacre - An Introduction. Bowling Green State University. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ↑ Strom, Karen (1995). The Massacre at Wounded Knee. Karen Strom.

- ↑ Associated Press, "North Dakota to appeal ruling on Sioux mascot", 2005-09-25. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ Tribal Resolutions and other Resolutions asking for the removal of the "Fighting Sioux" moniker and name. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ Ward Churchill, A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1997), p. 240.

- ↑ Winona LaDuke, All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life, (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1999), 141.

Bibliography

- Christafferson, Dennis M. (2001). Sioux, 1930-2000. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 821-839). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001a). Sioux until 1850. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718-760). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001b). Teton. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 794-820). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Hein, David (Advent 2002). "Episcopalianism among the Lakota / Dakota Indians of South Dakota." The Historiographer, vol. 40, pp. 14-16. [The Historiographer is a publication of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church and the National Episcopal Historians and Archivists.]

- Hein, David (1997). "Christianity and Traditional Lakota / Dakota Spirituality: A Jamesian Interpretation." The McNeese Review, vol. 35, pp. 128-38.

- Matson, William and Frethem, Mark (2006). Producers. "The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree." The Crazy Horse family tells their oral history and with explanations of Lakota spirituality and culture on DVD. (Publisher is Reelcontact.com)

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). The Siouan languages. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94-114). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Albers, Patricia C. (2001). Santee. In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 761-776). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970.

- Christafferson, Dennis M. (2001). Sioux, 1930-2000. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 821-839). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Cox, Hank H. (2005). Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House. ISBN 1-58182-457-2.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001a). Sioux until 1850. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718-760). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001b). Teton. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 794-820). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001c). Yankton and Yanktonai. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 777-793). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- DeMallie, Raymond J.; & Miller, David R. (2001). Assiniboine. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 572-595). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Getty, Ian A. L.; & Gooding, Erik D. (2001). Stoney. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 596-603). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Hein, David (Advent 2002). "Episcopalianism among the Lakota / Dakota Indians of South Dakota." The Historiographer, vol. 40, pp. 14-16. [The Historiographer is a publication of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church and the National Episcopal Historians and Archivists.]

- Hein, David (1997). "Christianity and Traditional Lakota / Dakota Spirituality: A Jamesian Interpretation." The McNeese Review, vol. 35, pp. 128-38.

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). The Siouan languages. In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94-114). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Sullivan, Maurice S.: "Jedediah Smith, Trader and Trail Breaker," New York Press of the Pioneers (1936) contains 'politically incorrect' white man's terminology and stereotypical attitudes toward the 'Indians'.

- Robert M. Utley, "The Last Days of the Sioux Nation" (Yale University, 1963) ISBN 0-300-00245-9

External links

- Lakhota Sioux Heritage Language & Culture Site

- Dakota Blues: The History of The Great Sioux Nation

- The Yanktonai (Edward S. Curtis)

- Lakota Language Consortium

- Winter Counts a Smithsonian exhibit of the annual icon chosen to represent the major event of the past year

- Rosebud Indian Reservation Land of the Sicangu Lakota Oyate

- Dakota Language and Culture Encyclopedia

- Dakota Blues: The History of The Great Sioux Nation

- Lakhota.Com The Leading Lakota Sioux Resource teaching Language and History since 1995 - run by members of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

- The Teton Sioux (Edward S. Curtis)

- Lakota Language Consortium (Indiana)

- Lakota Winter Counts a Smithsonian exhibit of the annual icon chosen to represent the major event of the past year

- Lakota Herbs (Canada)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.