Serpent

- For other uses, see Serpent (disambiguation)

Serpent is a word of Latin origin (serpens, serpentis) that is normally substituted for "snake" in a specifically mythic or religious context, in order to distinguish such creatures from the field of biology.

General symbolism

The serpent is one of the oldest and most widespread mythological symbols. There is some overlap of the themes that mythological serpents represent in various cultures. The snake's venom is associated with the chemicals of plants and fungi that have the power to either heal, poison or provide expanded consciousness (and even the elixir of life and immortality) through divine intoxication. The snake was often considered one of the wisest animals because of its herbal knowledge and entheogenic association, being (close to the) divine. It's habitat in the earth between the roots of plants made it an animal with chthonic properties connected to the afterlife and immortality. This is also expressed by the way a snake sheds its skin and comes forth from the lifeless husk glistening and fresh, making it a universal symbol of renewal, rebirth and the regeneration that may lead to immortality.

Sometimes serpents and dragons are used interchangeably, having similar symbolic functions. The venom of the serpent is thought to have a fiery quality similar to a fire spitting dragon. The Greek Ladon and the Norse Níðhöggr are sometimes described as serpents and sometimes as dragons. In Germanic mythology, serpent (OE: wyrm, OHG: wurm, ON: ormr) is used interchangeable with the Greek borrowing dragon (OE: draca, OHG: trahho, ON: dreki). In China, the Indian serpent nāga was equated with the lóng or Chinese dragon. The Aztec and Toltec serpent god Quetzalcoatl also has dragon like wings, like its equivalent in Mayan mythology Gukumatz ("feathered serpent").

Sea serpents were giant cryptozoological creatures once believed to live in water, such as the sea monster Leviathan or the Loch Ness Monster. If they were referred to as "sea snakes", they were understood to be the actual snakes that live in Indo-Pacific waters (Family Hydrophiidae).

Cosmic serpents

The serpent, when forming a ring with its tail in its mouth, is a clear and widespread symbol of the "All-in-All", the totality of existence, infinity and the cyclic nature of the cosmos. The most well known version of this is the Aegypto-Greek Ourobouros. It is believed to have been inspired by the Milky Way as some ancient texts refer to a serpent of light residing in the heavens.

In Norse mythology, the World Serpent (or Midgard serpent) known as Jörmungandr encircled the world in the ocean's abyss biting its own tail.

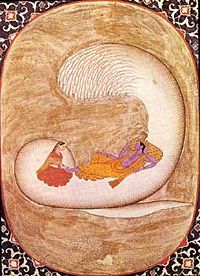

In Hindu mythology, Vishnu is said to sleep while floating on the cosmic waters on the serpent Shesha. In the Puranas Shesha is said to hold all the planets of the universe on his hoods and to constantly sing the glories of Vishnu from all his mouths. He is sometimes referred to as "Ananta-Shesha" which means "Endless Shesha." In the Puranas, Shesha loosens Mount Mandara for it to be used as a churning rod by the Asuras and Devas to churn the ocean of milk in the heavens in order to make Soma (or Amrita), the divine elixir of immortality. As a churning rope another giant serpent called Vasuki is used.

In pre-Columbian Central America Quetzalcoatl was sometimes depicted as biting its own tail. The mother of Quetzalcoatl was the Aztec goddess Coatlicue ("the one with the skirt of serpents"), also known as Cihuacoatl ("The Lady of the serpent"). Her function and appearance bear some resemblance with the Hindu goddess Kali, who is also accompanied by serpents. Quetzalcoatl's father was Mixcoatl ("Cloud Serpent"). He was identified with the Milky Way, the stars and the heavens in several Mesoamerican cultures.

The demi-god Aidophedo of the West African Ashanti is also a serpent biting its own tail. In Dahomey mythology of Benin in West Africa, the serpent that supports everything on its many coils was named Dan. In the Vodun of Benin and Haiti Ayida-Weddo (a.k.a. Aida-Wedo, Aido Quedo, "Rainbow-Serpent") is a spirit of fertility, rainbows and snakes, and a companion or wife to Dan, the father of all spirits. As Vodun was exported to Haiti through the slave trade, Dan became Danballah, Damballah or Damballah-Wedo. Because of his association with snakes, he is sometimes disguised as Moses, who carried a snake on his staff. He is also thought by many to be the same entity of Saint Patrick, known as a snake banisher.

In Greek Mythology, the serpent Hydra is a star constellation representing either the serpent thrown angrily into the sky by Apollo or the Lernaean Hydra as defeated by Heracles for one of his Twelve Labours. The constellation Serpens represents a snake being tamed by Ophiuchus the snake-handler, another constellation. The most recent interpretation is that Ophiuchus represents the healer Asclepius. Another possibility is that the figure represents the Trojan priest Laocoön, who was killed by a pair of sea serpents sent by the gods after he warned the Trojans not to accept the Trojan Horse. A third possibility is Apollo wrestling with the Python to take control of the oracle at Delphi.

Serpents in Cross-cultural Perspective

In many myths the chthonic serpent (sometimes a pair) lives in or is coiled around a Tree of Life situated in a divine garden. In the Genesis story of the Torah and Biblical Old Testament, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is situated in the Garden of Eden together with the tree of immortality. In Greek mythology Ladon coiled around the tree in the garden of the Hesperides protecting the entheogenic golden apples.

Similarly Níðhöggr the dragon of Norse mythology eats from the roots of the Yggdrasil the World Tree.

Under yet another Tree (the Bodhi tree of Enlightenment), the Buddha sat in ecstatic meditation. When a storm arose, the mighty serpent king Mucalinda rose up from his place beneath the earth and enveloped the Buddha in seven coils for seven days, not to break his ecstatic state.

The Vision Serpent was also a symbol of rebirth in Mayan mythology. The Vision Serpent goes back to earlier Maya conceptions, and lies at the center of the world as the Mayans conceived it. "It is in the center axis atop the World Tree. Essentially the World Tree and the Vision Serpent, representing the king, created the center axis which communicates between the spiritual and the earthly worlds or planes. It is through ritual that the king could bring the center axis into existence in the temples and create a doorway to the spiritual world, and with it power" (Schele and Friedel, 1990: 68).

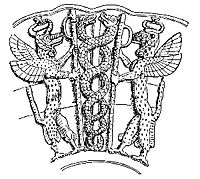

Sometimes the Tree of Life is represented (in a combination with similar concepts such as the World Tree and Axis mundi or "World Axis") by a staff such as those used by shamans. Examples of such staffs featuring coiled snakes in mythology are the caduceus of Hermes, the Rod of Asclepius and the staff of Moses. The oldest known representation is that of the Sumerian fertility god Ningizzida. Ningizzida was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head, eventually becoming a god of healing and magic. It is the companion of Dumuzi (Tammuz) with whom it stood at the gate of heaven. In the Louvre, there is a famous green steatite vase carved for king Gudea of Lagash (dated variously 2200–2025 B.C.E.) with an inscription dedicated to Ningizzida. Ningizzida was the ancestor of Gilgamesh, who according to the epic dived to the bottom of the waters to retrieve the plant of life. But while he rested from his labor, a serpent came and ate the plant. The snake became immortal, and Gilgamesh was destined to die.

Ningizzida has been popularised in the 20th C. by Raku Kei Reiki (a.k.a. "The Way of the Fire Dragon") where "Nin Giz Zida" is believed to be a fire serpent of Tibetan rather than Sumerian origin. Nin Giz Zida is another name for the ancient Hindu concept of Kundalini, a Sanskrit word meaning either "coiled up" or "coiling like a snake". Kundalini refers to the mothering intelligence behind yogic awakening and spiritual maturation leading to altered states of consciousness. There are a number of other translations of the term usually emphasizing a more serpentine nature to the word— e.g. 'serpent power'. It has been suggested by Joseph Campbell that the symbol of snakes coiled around a staff is an ancient representation of Kundalini physiology. The staff represents the spinal column with the snake(s) being energy channels. In the case of two coiled snakes they usually cross each other seven times, a possible reference to the seven energy centers called chakras.

In Egypt, Ra and Atum ("he who completes or perfects") were the same god, Atum, the "counter-Ra," was associated with earth animals, including the serpent: Nehebkau ("he who harnesses the souls") was the two headed serpent god who guarded the entrance to the underworld. He is often seen as the son of the snake goddess Renenutet, often confused with the snake goddess Wadjet.

The image of the serpent as the embodiment of the wisdom transmitted by Sophia was an emblem used by gnosticism, especially those sects that the more orthodox characterized as "Ophites" ("Serpent People"). The chthonic serpent was one of the earth-animals associated with the cult of Mithras. The Basilisk, the venomous "king of serpents" with the glance that kills, was hatched by a serpent, Pliny the Elder and others thought, from the egg of a cock. Such fantasies filled the medieval bestiary.

Outside Eurasia, in Yoruba mythology, Oshunmare was another mythic regenerating serpent.

The Rainbow Serpent (also known as the Rainbow Snake) is a major mythological being for Aboriginal people across Australia, although the creation stories associated with it are best known from northern Australia. As far away as Fiji, Ratumaibulu was a serpent god who ruled the underworld (and made fruit trees bloom).

Greek Mythology

see also: Dragons in Greek mythology

Serpents figured prominently in archaic Greek myths. According to some sources, Ophion ("serpent", a.k.a. Ophioneus), ruled the world with Eurynome before the two of them were cast down by Cronus and Rhea.

The Minoan Great Goddess brandished a serpent in either hand, perhaps evoking her role as source of wisdom, rather than her role as Mistress of the Animals (Potnia theron), with a leopard under each arm. It is not by accident that later the infant Heracles, a liminal hero on the threshold between the old ways and the new Olympian world, also brandished the two serpents that "threatened" him in his cradle. Classical Greeks did not perceive that the threat was merely the threat of wisdom. But the gesture is the same as that of the Cretan goddess.

Typhon the enemy of the Olympian gods is described as a vast grisly monster with a hundred heads and a hundred serpents issuing from his thighs, who was conquered and cast into Tartarus by Zeus, or confined beneath volcanic regions, where he is the cause of eruptions. Typhon is thus the chthonic figuration of volcanic forces. Amongst his children by Echidna are Cerberus (a monstrous three-headed dog with a snake for a tail and a serpentine mane), the serpent tailed Chimaera, the serpent-like chthonic water beast Lernaean Hydra and the hundred-headed serpentine dragon Ladon. Both the Lernaean Hydra and Ladon were slain by Heracles.

Python was the earth-dragon of Delphi, always represented in the vase-paintings and by sculptors as a serpent. Pytho was the chthonic enemy of Apollo, who slew her and remade her former home his own oracle, the most famous in Classical Greece.

Amphisbaena a Greek word, from amphis, meaning "both ways", and bainein, meaning "to go", also called the "Mother of Ants", is a mythological, ant-eating serpent with a head at each end. According to Greek mythology, the mythological amphisbaena was spawned from the blood that dripped from Medusa the Gorgon's head as Perseus flew over the Libyan Desert with it in his hand. Medusa and the other Gorgons were vicious female monsters with sharp fangs and hair of living, venomous snakes.

Asclepius, the son of Apollo, learned the secrets of keeping death at bay after observing one serpent bringing another (which Asclepius himself had fatally wounded) healing herbs. To prevent the entire human race from becoming immortal under Asclepius's care, Zeus killed him with a bolt of lightning. Asclepius' death at the hands of Zeus illustrates man's inability to challenge the natural order that separates mortal men from the gods. In honor of Asclepius, snakes were often used in healing rituals. Non-poisonous snakes were left to crawl on the floor in dormitories where the sick and injured slept. In The Library, Apollodorus claimed that Athena gave Asclepius a vial of blood from the Gorgons. Gorgon blood had magical properties: if taken from the left side of the Gorgon, it was a fatal poison; from the right side, the blood was capable of bringing the dead back to life.

Laocoön was allegedly a priest of Poseidon (or of Apollo, by some accounts) at Troy; he was famous for warning the Trojans in vain against accepting the Trojan Horse from the Greeks, and for his subsequent divine execution. Poseidon (some say Athena), who was supporting the Greeks, subsequently sent sea-serpents to strangle Laocoön and his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus. Another tradition states that Apollo sent the serpents for an unrelated offense, and only unlucky timing caused the Trojans to misinterpret them as punishment for striking the Horse.

Olympias, the mother of Alexander the Great and a princess of the primitive land of Epirus, had the reputation of a snake-handler, and it was in serpent form that Zeus was said to have fathered Alexander upon her; tame snakes were still to be found at Macedonian Pella in the 2nd century AD (Lucian, Alexander the false prophet) and at Ostia a bas-relief shows paired coiled serpents flanking a dressed altar, symbols or embodiments of the Lares of the household, worthy of veneration (Veyne 1987 illus p 211).

Torah and Biblical Old Testament

In the Hebrew Bible (the Tanach) of Judaism, the speaking serpent (nachash) in the Garden of Eden brought forbidden knowledge, but was not identified with Satan in the Book of Genesis. "Now the serpent was more cunning than any beast of the field which the Lord God has made," Genesis 3:1 reminded its readers. Nor is there any indication in Genesis that the Serpent was a deity in its own right, aside from the fact that the Pentateuch is not otherwise rife with talking animals. The identity of the Serpent as Satan is made explicit in the later writings of the Hebrew prophets and the New Testament of the Bible. Every word the Serpent spoke was in fact true, and its words were later confirmed by Yahweh in Gen. 3:22.

Though it was cursed for its role in the Garden, this was not the end of the Serpent, who continued to be venerated in the folk religion of Judah and was tolerated by official religion until the in time of king Hezekiah.

A conversion of a rod to a snake and back was believed to have been experienced by Moses and later by his brother Aaron according to Islamic, Christian, and Jewish hagiography:

- And the Lord said unto him, What is that in thine hand? And he said, A rod. And he said, Cast it on the ground. And he cast it on the ground, and it became a serpent; and Moses fled from before it. And the Lord said unto Moses, Put forth thine hand, and take it by the tail. And he put forth his hand and caught it and it became a rod in his hand. (Exodus 4:2-4)

The Book of Numbers provides an origin for an archaic bronze serpent associated with Moses, with the following narratives:

- "21.6. And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died. 7. Therefore the people came to Moses, and said, We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord, and against thee; pray unto the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us. And Moses prayed for the people. 8. And the Lord said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live. 9. And Moses made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived." (Book of Numbers 21:6-9)

When the young reforming king Hezekiah came to the throne of Judah in the late 8th century:

- "He removed the high places, and brake the images, and cut down the groves, and brake in pieces the brasen serpent that Moses had made: for unto those days the children of Israel did burn incense to it: and he called it Nehushtan." 2 Kings 18:4.

In Christianity, a connection between the Serpent and Satan is strongly made, and Genesis 3:14 where God curses the serpent, is seen in that light: "And the Lord God said unto the serpent, Because thou hast done this, thou art cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life". Some feel that this seems to indicate that the serpent had legs prior to this punishment. But if the lying serpent was in fact Satan himself (as he is called THE serpent or dragon), rather than an ordinary snake simply possessed by Satan, then the reference to crawling and dust is purely symbolic reference to his ultimate humiliation and defeat.

New Testament

In the Gospel of Matthew 3:7, John the Baptist calls the Pharisees and Saducees visiting him a `brood of vipers`. Later in Matthew 23:33, Jesus himself uses this imagery, observing: "Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of Gehenna?" ("Hell" is the usual translation of Jesus' word Gehenna.)

Although in the minority, there are at least a couple of passages in the New Testament that do not present the snake with negative connotation. When sending out the twelve apostles, Jesus exhorted them "Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves" (Matthew 10:16).

Jesus made a comparison between himself and the setting up of the snake on the hill in the desert by Moses:

- And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life (John 3:14-15).

In this comparison Jesus was not so much connecting himself to the serpent, but showing the analogy of his being a divinely provided object of faith, through which God would provide salvation, just as God provided healing to those who looked in faith to the brass serpent. The other most significant reference to the serpent in the New Testament occurs in Revelation 12:9, where the identity of the serpent in Genesis is made explicit:

- "The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray..."

This verse lends support to the view that of the serpent being Satan himself, which helps to explain, as well, why Eve was not surprised to be spoken to by the serpent—it was not a talking snake, but a beautiful and intelligent (yet evil) angelic being.

- Veyne, Paul, 1987. A History of Private Life : 1. From Pagan Rome to Byzantium

Snake handling is a religious ritual in a small number of Christian churches in the U.S., usually characterized as rural and Pentecostal. Practitioners believe it dates to antiquity and quote the Bible to support the practice, especially:

- "And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." (Mark 16:17-18)

- "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you." (Luke 10:19)

Rod of Asclepius vs. Caduceus in modern medicine

Snakes entwined the staffs both of Hermes (the caduceus) and of Asclepius, where a single snake entwined the rough staff. On Hermes' caduceus, the snakes were not merely duplicated for symmetry, they were paired opposites. The wings at the head of the staff identified it as belonging to the winged messenger, Hermes, the Roman Mercury, who was the god of magic, diplomacy and rhetoric, of inventions and discoveries, the protector both of merchants and that allied occupation, to the mythographers' view, of thieves. It is however Hermes' role as psychopomp, the escort of newly-deceased souls to the afterlife, that explains the origin of the snakes in the caduceus since this was also the role of the Sumerian entwined serpent god Ningizzida, with whom Hermes has sometimes been equated with.

In Late Antiquity, as the arcane study of alchemy developed, Mercury was understood to be the protector of those arts too and of arcane or occult "Hermetic' information in general. Chemistry and medicines linked the rod of Hermes with the staff of the healer Asclepius, which was wound with a serpent; it was conflated with Mercury's rod, and the modern medical symbol— which should simply be the rod of Asclepius— often became Mercury's wand of commerce. Art historian Walter J. Friedlander, in The Golden Wand of Medicine: A History of the Caduceus Symbol in Medicine (1992) collected hundreds of examples of the caduceus and the rod of Asclepius and found that professional associations were just somewhat more likely to use the staff of Asclepius, while commercial organizations in the medical field were more likely to use the caduceus.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Joseph Campbell, Occidental Mythology: the Masks of God, 1964: Ch. 1, "The Serpent's Bride"

- John Bathurst Deane, The Worship of the Serpent, 1833. [1]

- Lewis Richard Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, 1896.

- Joseph Eddy Fontenrose, Python; a study of Delphic myth and its origins, 1959.

- Jane Ellen Harrison, Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion, 1912. cf. Chapter IX, p.329 especially, on the slaying of the Python. [2] [3]

- Joseph Lewis Henderson and Maud Oakes, The Wisdom of the Serpent. The tribal initiation of the shaman, the archetype of the serpent, exemplifies the death of the self and a transcendent rebirth. Analytical psychology offers insights on the meaning of death symbolism and the serpent symbol.

External links

- The caduceus vs the staff of Asclepius

- Dr Robert T. Mason, "The Divine serpent in myth and legend," 1999

- Links to further serpent myth

- Nagas and Serpents

- Snakes of the bible and the koran

- Scientific American - Offerings to a Stone Snake Provide the Earliest Evidence of Religion by J. R. Minkel 01/12/06

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.