Difference between revisions of "Penal colony" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}} | ||

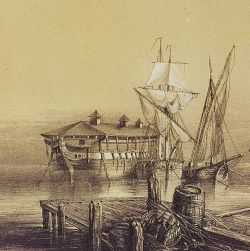

| + | [[File:Lebreton engraving-09-hulk.jpg|thumb|250px|A prison hulk in Toulon harbor]] | ||

| + | A '''penal colony''' was a colonial community, often established in an underdeveloped part of a state’s territory, to detain societal prisoners. Prisoners were generally used for punitive labor on a far larger scale than general [[prison]] farms. Throughout history, penal labor has represented a common form of [[punishment]] throughout numerous countries worldwide. Parallels can be drawn between the ''katorga'' and the American chain gang, or the convict settlements in [[Australia]], which played a large part in founding and developing the large country. The historic use of penal labor partially attempted to address the financial costs of keeping prisoners, although this sometimes led to unjust sentences to increase the numbers of prison laborers. The majority of penal colonies existing worldwide have now been abolished, ending this method of often cruel and unusual punishment. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Penal systems== | ||

| − | + | In the '''penal colony''' system, prisoners were deported to distant areas from their homelands to prevent successful escape and to discourage prisoners from returning home after their sentences expired. Penal colonies were often located in inhospitable frontier lands, where unpaid prisoners labored on behalf of their country’s colonial settlement efforts. Prisoners remained a central source of [[labor]] even after the discovery of immigration labor, due to their zero wage pay. To generate increases in cheap labor, many countries unjustly expelled a large portion of their poor population to penal colonies for trivial or dubious offenses. Eighteenth century [[Great Britain]] employed such tactics in the establishment of penal colonies in parts of [[Penal colony#North America|North America]] and [[Penal colony#Australia|Australia]]. | |

| − | + | Many detained prisoners of penal colonies faced severe [[prison]] regimes and were subject to physical punishment during their terms of hard labor. Detainees often died from hunger, [[disease]], exhaustion, or medical neglect, and were killed if they attempted to escape. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Chain gangs=== | |

| + | [[Image:Chain gang - convicts going to work nr. Sidney N.S. Wales.jpg|thumb|250px|right|A chain gang of convicts going to work near Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Dated 1842.]] | ||

| − | + | A chain gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging labor, such as chipping stone, often along a highway. Historically, the primary purpose of a chain gang was punitive, with any benefits of the labor being outweighed by the costs and risks involved in operating a chain gang. Their presence in public was to serve as a deterrent to [[crime]], especially among black African Americans. A traditional chain gang is almost universally regarded as being a form of cruel and unusual [[punishment]], and that view, combined with the economic cost of operating chain gangs, led to their decline in the 1950s. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The use of chain gangs was common in Australia, when transportation to the penal colony of Norfolk Island ended, and prisoners had to complete their sentences within areas of New South Wales colonized by law-abiding settlers. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Great Britain== | |

| + | ===North America=== | ||

| + | The British Empire used [[North America]] as a penal colony through a system of indentured service; North America’s province of Georgia was originally established for such purposes. British convicts would be transported by private sector merchants and auctioned off to plantation owners upon arrival in the colonies. During its course of settlement it is estimated that more than 50,000 British convicts were banished to colonial America, a population representing one-quarter of all British emigrants during the eighteenth century. | ||

| − | + | ===Australia=== | |

| + | After the [[American Revolutionary War]], a similar system of Great Britain’s indentured service was transported to [[Australia]]. Britain quickly established parts of the continent as penal colonies and founded [[Penal colony#Norfolk Island|Norfolk Island]], [[Penal colony#Van Diemen's Land|Van Diemen's Land]], and [[Penal colony#New South Wales|New South Wales]] as such. British affiliates of [[trade union|Trade Unionism]] and advocates of [[Ireland|Irish]] Home Rule often received sentences that required punitive transportation for terms of hard labor in these Australian colonies. | ||

| − | + | ====Norfolk Island==== | |

| − | + | Norfolk Island is considered the first established penal colony within the Australian continent. Before the sailing of the first British fleet to establish the continent’s first territory, British Governor Arthur Phillip was specifically instructed to colonize its Eastern Norfolk Island to prevent the land from falling into the hands of the [[France|French]] who were also showing interest in the [[Pacific]]. When the fleet arrived at mainland Port Jackson in January of 1788, Phillip ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to lead a party of fifteen convicts and seven free men to establish the island and prepare for its commercial development. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | It was soon found that the [[flax]] found throughout Norfolk Island was difficult to prepare for manufacturing and required native skills. Two [[Māori]] men, indigenous to [[New Zealand]], were brought to the island to teach the colonists how to prepare and later [[weaving|weave]] the flax. The plan, however, would fail as weaving was the work of native women and the two men had little knowledge of it. The colonists also abandoned Norfolk Island’s potential pine timber industry as the wood was not resilient enough to craft masts. | |

| − | + | Regardless, more convicts arrived and the island was used as a farm to supply Sydney with [[cereal]], [[grain]], and [[vegetable]]s. However the majority of crops did not survive the overseas [[transportation]] due to salty winds, rats, and caterpillars. Sydney also lacked a natural safe harbor which proved to hinder [[communication]] and the transport of supplies between the island and the mainland. | |

| − | + | In March of 1790, with Sydney facing a widespread [[famine]], a great number of convicts and marines were transported to Norfolk Island via HMS ''Sirius'' to increase the island’s productivity. The attempt to relieve Sydney’s situation later turned to disaster when the ship was wrecked and most stores were destroyed. The entire crew was marooned for ten months. This news was met in Sydney with great concern as Norfolk Island was now further cut off from the mainland. With the subsequent arrival of England’s Second Fleet carrying a cargo of sick and abused convicts, the city had even more pressing problems to contend with. | |

| − | + | As early as 1794, British officials suggested the island’s closure as a penal settlement as it proved too remote and difficult for shipments, and far too costly to maintain. By 1803, the British Secretary of State called for the dismantling of the Norfolk Island military establishment, and exported settlers and convicts to Southern Van Diemen's Land. In February of 1805 the first group, comprised mainly of convicts, their families, and military personnel, departed from Norfolk Island. By 1808, less than 200 settlers remained and formed a small settlement until all societal remnants were removed in 1813 by a small party instructed to slaughter livestock and destroy all buildings leaving little incentive for another European power to colonize the island. The island lay abandoned until 1825. | |

| − | + | In 1824, the British government instructed the Governor of New South Wales, Thomas Brisbane, to occupy Norfolk Island as a place to send the worst of convict settlers. Its remoteness, seen previously as a disadvantage, was now viewed as an asset for the detention of men who had committed further crimes since arriving in New South Wales. Governor General George Arthur of Van Diemen's Land believed that prisoners sent to Norfolk Island “should on no account be permitted to return” and the reformation of convicts was dismissed as an objective of the Norfolk Island penal settlement. | |

| − | + | In 1846, a report of magistrate Robert Pringle Stuart exposed Norfolk Island’s scarcity and poor quality of food, inadequacy of housing, horrors of [[torture]], and incessant flogging, insubordination of convicts, and corruption of overseers. Bishop Robert Willson later visited Norfolk Island and reported similar findings to the House of Lords, who came to realize the enormity of atrocities perpetrated under the British flag and attempted to remedy the evils. Rumors of resumed atrocities brought Willson back in 1852 and produced a further damning report. | |

| − | + | Only a handful of convicts left any written record of such conditions, their descriptions of living and working conditions, food and housing, and, in particular, the punishments given for seemingly trivial offenses are unremittingly horrifying, describing a settlement devoid of all human decency, under the iron rule of the tyrannical autocratic commandants. | |

| − | The second penal settlement began to be wound down by the British Government after 1847 and the last convicts were | + | The second resurgence of Norfolk Island as a penal settlement began to be wound down by the British Government after 1847, and the last convicts were transported to [[Tasmania]] in May 1855. |

====Van Diemen's Land==== | ====Van Diemen's Land==== | ||

| − | ' | + | {{readout||right|250px|[[Tasmania]] was called Van Diemen's Land when it was the primary British penal colony in [[Australia]]}} |

| − | + | Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by the British for the island of [[Tasmania]], now part of Australia. The [[Netherlands|Dutch]] explorer [[Abel Tasman]] was the first European to discover Tasmania. He named the island in honor of [[Anthony van Diemen]], Governor-General of the Dutch East India Company, who had sent Tasman on his voyage of discovery in 1642. In 1803, the island was colonized by the British Empire as a penal colony with the name Van Diemen's Land. | |

| − | In | ||

| + | From the 1830s to the abolition of penal transportation in 1853, Van Diemen's Land was the primary penal colony in Australia. Following the suspension of transportation to Norfolk Island, all convicts sent to Australia served their sentences as assigned labor to free settlers, or in [[Penal colony#Chain Gangs|chain gangs]] assigned to public works. Only the most difficult convicts were sent to the Tasman Peninsula prison known as Port Arthur. In total, some 75,000 convicts were transported to Van Diemen's Land, or about 40 percent of all convicts sent to Australia. | ||

| − | + | Convicts completing their sentences or earning their tickets-of-leave often promptly left Van Diemen's Land to settle in the new free colony of Victoria. Tensions often ran high between the free settlers and the "Vandemonians" as they were termed, particularly during the Victorian Gold Rush when a flood of settlers from Van Diemen's Land rushed to the Victorian [[gold]] fields. Complaints from Victorians about recently released convicts from Van Diemen's Land re-offending in Victoria was one of the contributing reasons for the eventual abolition of transportation to Van Diemen's Land in 1853. | |

| − | + | In order to remove the unsavory connotations with crime associated with its name, in 1856 Van Diemen's Land was renamed [[Tasmania]] in honor of [[Abel Tasman]]. The last penal settlement in Tasmania at Port Arthur finally closed in 1877. | |

| − | |||

| − | In order to remove the | ||

===India=== | ===India=== | ||

| − | + | The British Empire also established various penal colonies in colonial [[India]]. Two of the most infamous were located on the [[Penal colony#Andaman Islands|Andaman Islands]], comprised of multiple settlements, and at [[Penal colony#Hijli|Hijli]]. | |

====Andaman Islands==== | ====Andaman Islands==== | ||

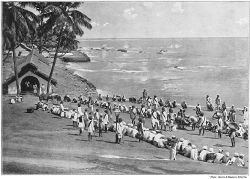

| − | + | [[File:Andamans QE3 116.jpg|thumb|250px|Prisoners in the Andaman Islands (late 1890s)]] | |

| − | + | British accounts of the [[Andaman Islands]] often leave the impression that the island settlements were models of progressive penal reform and were focused predominately around farm labor. Though few supervisors were appointed, total island population numbered more than 10,000. The [[education]] of school-aged children of prisoners was compulsory, and all convicts were given free medical attention at one of the four island hospitals. The settlement boasted a safe harbor and high success rate, turning long-sentence convicts into self-respecting men and women. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Indian accounts, however, paint a contrasting picture. From the time of its development in 1858, the settlement was first and foremost a repository for political prisoners. The Cellular Jail at Port Blair included 698 cells designed for solitary confinement. The Viper Chain Gang Jail on Viper Island was reserved for the worst of criminals and was also the site of prisoner [[hanging]]s. In the twentieth century, it became a convenient place to house prominent members of India's independence movement, and it was here that on December 30, 1943, during [[Japan]]ese occupation that the first flag of Indian independence was raised. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | At the close of the Second World War the British government announced its intention to abolish the penal settlement | + | At the close of the [[Second World War]], the British government announced its intention to abolish the penal settlement and proposed the employment of former inmates in an initiative to develop the island's fisheries, timber, and agricultural resources. In exchange, inmates would be granted return passage to the Indian mainland, or the right to settle on the islands. The penal colony was eventually closed on August 15, 1947, when India gained its independence. It has since served as a [[museum]] to the independence movement. |

====Hijli==== | ====Hijli==== | ||

[[Image:IIT Kharagpur Old Building 1951.jpg|thumb|300px|The administrative building of Hijli Detention Camp (September 1951)]] | [[Image:IIT Kharagpur Old Building 1951.jpg|thumb|300px|The administrative building of Hijli Detention Camp (September 1951)]] | ||

| − | + | Hijli Detention Camp, located in the district of Midnapore West Bengal, was significant in the struggle against the [[British Raj]] in the early twentieth century. Because the large numbers of Indian nationalists who participated in the armed struggle against the early British occupation could not be accommodated in ordinary [[jail]]s, the British Government decided to establish a system of detention camps. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The first, located in Buxa Fort was quickly followed by the 1930 creation of the Hijli Detention Camp. A significant moment in the struggle against British rule occurred at the Hijli Detention Camp on September 16, 1931, when two unarmed detainees were shot dead by the British Police. National leaders were enraged and voiced strong protests against the British Raj over this incident. The Hijli Detention Camp was closed in 1937, but reopened again in 1940. Two years later the camp was officially closed and all detainees were transferred elsewhere. | ||

| + | In May 1950, the first Indian Institute of Technology was housed at the original site of the detention camp. In 1990, former buildings were converted to house the Nehru Museum of Science and Technology. | ||

==France== | ==France== | ||

| − | + | The French Empire also sent criminals to tropical penal settlements. [[Penal colony#Devil's Island|Devil's Island]] in [[French Guiana]], lasting 1852-1939, received [[forgery|forgers]] and other criminals. [[Penal colony#New Caledonia|New Caledonia]] in South Sea [[Melanesia]] received dissident rebels as well as convicted criminals. | |

===Devil's Island=== | ===Devil's Island=== | ||

| − | + | Devil’s Island is the smallest of three islands located off the coast of [[French Guiana]] and held a notorious French penal colony until 1946. The penitentiary atop the rocky, palm-covered island was first opened by Emperor [[Napoleon III]] of France in 1852 and quickly became one of the most infamous prisons in history. In addition to the prison on the island, prison facilities were located on the French mainland at Kourou. | |

| − | |||

| − | The rocky, palm-covered island | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Used by France from 1852 to 1946, the inmates ranged from political prisoners to the most hardened of [[theft|thieves]] and [[murder]]ers. Many of the 80,000 prisoners that faced the harsh conditions at the disease-infested island were never seen again. Escape options, other than by sea, included travel through a dense jungle, and very few convicts managed to escape. A limited number of convicted women were also sent to French Guiana, with instructions to marry the freed male inmates. However the results of this idea were poor and the government ceased the practice in 1907. | |

| − | + | The horrors of the penal settlement became notorious in 1895 with the publicity surrounding the experience of French army captain [[Alfred Dreyfus]] who had been wrongfully [[the Dreyfus Affair|convicted]] of [[treason]] and was sent to Devil’s Island. | |

| + | In 1938, the French government stopped sending prisoners to Devil's Island, and in 1952 the prison closed permanently. Most of the prisoners returned to mainland France, though some chose to remain in French Guiana. | ||

| + | Several movies, songs, a stage play, as well as a number of books have featured Devil's Island. The most famous is a 1970 best-selling book, also made into a popular movie, entitled ''Papillon'' by former Devil's Island convict Henri Charriere, which tells of his numerous alleged escape attempts. | ||

| − | + | ===New Caledonia=== | |

| + | The island of [[New Caledonia]] was made a French possession in 1853, in an attempt by [[Napoleon III]] to rival the British colonies in [[Australia]] and [[New Zealand]]. Between 1854 and 1922 France sent a total of 22,000 convicted felons to penal colonies along the south-west coast of the island; this number includes regular criminals as well as political prisoners such as Parisian socialists and Kabyle nationalists. Towards the end of the penal colony era, free European settlers (including former convicts) and Asian contract workers by far out-numbered the population of forced workers. The indigenous Kanak populations declined drastically in that same period due to introduced diseases and an [[apartheid]]-like system called ''Code de l'Indigénat,'' which imposed severe restrictions on their livelihood, freedom of movement, and land ownership. | ||

==Russia== | ==Russia== | ||

| − | + | Both Imperial [[Russia]] and the [[Soviet Union]] used [[Siberia]] as a penal colony for criminals and public dissidents. Though geographically contiguous with mainland Russia, Siberia provided both remoteness and a harsh [[climate]] for the worst of society’s prisoners. Penal systems like the ''[[Gulag]]'' and its tsarist predecessor, the ''[[Penal colony#Katorga|katorga]],'' provided penal labor to develop [[forestry]], logging, and [[mining]] industries, construction enterprises, and highway and railroad construction across Siberia. | |

| − | |||

| − | Both Imperial [[Russia]] and the [[Soviet Union]] used [[Siberia]] as a penal colony for criminals and | ||

===Katorga=== | ===Katorga=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The ''katorga'' was a seventeenth century system of penal servitude of the prison farm type used in Imperial Russia. Prisoners were sent to remote camps in vast uninhabited areas of Siberia, where volunteer laborers were unavailable, and forced to perform hard manual labor. Unlike [[concentration camp]]s, a ''katorga'' was within the normal judicial system of Imperial Russia, though both share the same main features of confinement, simplified facilities, and [[forced labor]] usually involving hard, unskilled, or semi-skilled work. The most common occupations in ''katorga'' camps were [[mining]] and timber works. | |

| − | + | [[File:Russian prisoners of Amur Railway.jpg|thumb|250px|Russian prisoners at an Amur Cart Road camp, between 1908 and 1913]] | |

| + | ''Katorgas'' were established in the seventeenth century in under populated areas of Siberia and the Russian Far East. Nonetheless, a few prisoners successfully escaped back to populated areas. Since the seventeenth century, [[Siberi]]a gained its fearful connotation of [[punishment]], which was further enhanced by the [[Soviet Union]]’s [[Gulag]] system that developed after the [[Russian Revolution of 1917]]. | ||

| − | + | After a change in Russian penal law in 1847, [[exile]] and ''katorga'' became common penalties to the participants of national uprisings within the Russian Empire. This led to an increasing number of [[Poland|Polish]] people being sent to Siberia to perform labor under ''katorga'' systems. They were known as "Sybiraks," some of them remaining there after their sentences to form a Polish minority in Siberia. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Anton Chekhov]], the famous Russian writer and playwright, visited the ''katorga'' settlements of Russia’s Far East Sakhalin island in 1891. Writing about the conditions, he criticized the shortsightedness and incompetence of the officials in charge that allowed for conditions of poor living standards, waste of government funds, and low productivity. After the Russian Revolution, Russia’s penal system was taken over by the Bolsheviks, eventually transforming them into [[Gulag]] labor camps. | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | + | *Belbenoit, René. ''Hell on Trial.'' Translated from the Original French Manuscript by Preston Rambo. E. P Dutton & Co. Reprint by Blue Ribbon Books, New York, 1941. | |

| − | + | *Belbenoit, René. 1938. ''Dry guillotine: Fifteen years among the living dead.'' Reprint: Berkley, 1975. ISBN 0425029506 | |

| − | + | *Charrière, Henri. ''Papillon.'' Perennial, 2001. ISBN 978-0060934798 | |

| − | *Belbenoit, René | + | *Kropotkin, P. ''In Russian and French Prisons.'' London: Ward and Downey, 1887. |

| − | *Belbenoit, René. 1938. ''Dry guillotine: Fifteen years among the living dead'' | ||

| − | *Charrière, Henri. ''Papillon'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | == External Links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 23, 2022. | ||

| + | * [http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/Anarchist_Archives/kropotkin/prisons/chap1.html In Russian and French Prisons] by P.Kropotkin. | ||

| + | *[http://www.angelfire.com/sc2/mplu/time.html The Labor of Doing Time] by Julie Browne. | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit8|Penal_colony|72811112|Andaman_Islands|77851233|Hijli_Detention_Camp|74543327|Devil's_Island|77964221|Katorga|78510598|Norfolk_Island|79437635|Van_Diemen's_Land|71437798|Chain_gang|85392418}} |

Latest revision as of 07:14, 23 November 2022

A penal colony was a colonial community, often established in an underdeveloped part of a state’s territory, to detain societal prisoners. Prisoners were generally used for punitive labor on a far larger scale than general prison farms. Throughout history, penal labor has represented a common form of punishment throughout numerous countries worldwide. Parallels can be drawn between the katorga and the American chain gang, or the convict settlements in Australia, which played a large part in founding and developing the large country. The historic use of penal labor partially attempted to address the financial costs of keeping prisoners, although this sometimes led to unjust sentences to increase the numbers of prison laborers. The majority of penal colonies existing worldwide have now been abolished, ending this method of often cruel and unusual punishment.

Penal systems

In the penal colony system, prisoners were deported to distant areas from their homelands to prevent successful escape and to discourage prisoners from returning home after their sentences expired. Penal colonies were often located in inhospitable frontier lands, where unpaid prisoners labored on behalf of their country’s colonial settlement efforts. Prisoners remained a central source of labor even after the discovery of immigration labor, due to their zero wage pay. To generate increases in cheap labor, many countries unjustly expelled a large portion of their poor population to penal colonies for trivial or dubious offenses. Eighteenth century Great Britain employed such tactics in the establishment of penal colonies in parts of North America and Australia.

Many detained prisoners of penal colonies faced severe prison regimes and were subject to physical punishment during their terms of hard labor. Detainees often died from hunger, disease, exhaustion, or medical neglect, and were killed if they attempted to escape.

Chain gangs

A chain gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging labor, such as chipping stone, often along a highway. Historically, the primary purpose of a chain gang was punitive, with any benefits of the labor being outweighed by the costs and risks involved in operating a chain gang. Their presence in public was to serve as a deterrent to crime, especially among black African Americans. A traditional chain gang is almost universally regarded as being a form of cruel and unusual punishment, and that view, combined with the economic cost of operating chain gangs, led to their decline in the 1950s.

The use of chain gangs was common in Australia, when transportation to the penal colony of Norfolk Island ended, and prisoners had to complete their sentences within areas of New South Wales colonized by law-abiding settlers.

Great Britain

North America

The British Empire used North America as a penal colony through a system of indentured service; North America’s province of Georgia was originally established for such purposes. British convicts would be transported by private sector merchants and auctioned off to plantation owners upon arrival in the colonies. During its course of settlement it is estimated that more than 50,000 British convicts were banished to colonial America, a population representing one-quarter of all British emigrants during the eighteenth century.

Australia

After the American Revolutionary War, a similar system of Great Britain’s indentured service was transported to Australia. Britain quickly established parts of the continent as penal colonies and founded Norfolk Island, Van Diemen's Land, and New South Wales as such. British affiliates of Trade Unionism and advocates of Irish Home Rule often received sentences that required punitive transportation for terms of hard labor in these Australian colonies.

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island is considered the first established penal colony within the Australian continent. Before the sailing of the first British fleet to establish the continent’s first territory, British Governor Arthur Phillip was specifically instructed to colonize its Eastern Norfolk Island to prevent the land from falling into the hands of the French who were also showing interest in the Pacific. When the fleet arrived at mainland Port Jackson in January of 1788, Phillip ordered Lieutenant Philip Gidley King to lead a party of fifteen convicts and seven free men to establish the island and prepare for its commercial development.

It was soon found that the flax found throughout Norfolk Island was difficult to prepare for manufacturing and required native skills. Two Māori men, indigenous to New Zealand, were brought to the island to teach the colonists how to prepare and later weave the flax. The plan, however, would fail as weaving was the work of native women and the two men had little knowledge of it. The colonists also abandoned Norfolk Island’s potential pine timber industry as the wood was not resilient enough to craft masts.

Regardless, more convicts arrived and the island was used as a farm to supply Sydney with cereal, grain, and vegetables. However the majority of crops did not survive the overseas transportation due to salty winds, rats, and caterpillars. Sydney also lacked a natural safe harbor which proved to hinder communication and the transport of supplies between the island and the mainland.

In March of 1790, with Sydney facing a widespread famine, a great number of convicts and marines were transported to Norfolk Island via HMS Sirius to increase the island’s productivity. The attempt to relieve Sydney’s situation later turned to disaster when the ship was wrecked and most stores were destroyed. The entire crew was marooned for ten months. This news was met in Sydney with great concern as Norfolk Island was now further cut off from the mainland. With the subsequent arrival of England’s Second Fleet carrying a cargo of sick and abused convicts, the city had even more pressing problems to contend with.

As early as 1794, British officials suggested the island’s closure as a penal settlement as it proved too remote and difficult for shipments, and far too costly to maintain. By 1803, the British Secretary of State called for the dismantling of the Norfolk Island military establishment, and exported settlers and convicts to Southern Van Diemen's Land. In February of 1805 the first group, comprised mainly of convicts, their families, and military personnel, departed from Norfolk Island. By 1808, less than 200 settlers remained and formed a small settlement until all societal remnants were removed in 1813 by a small party instructed to slaughter livestock and destroy all buildings leaving little incentive for another European power to colonize the island. The island lay abandoned until 1825.

In 1824, the British government instructed the Governor of New South Wales, Thomas Brisbane, to occupy Norfolk Island as a place to send the worst of convict settlers. Its remoteness, seen previously as a disadvantage, was now viewed as an asset for the detention of men who had committed further crimes since arriving in New South Wales. Governor General George Arthur of Van Diemen's Land believed that prisoners sent to Norfolk Island “should on no account be permitted to return” and the reformation of convicts was dismissed as an objective of the Norfolk Island penal settlement.

In 1846, a report of magistrate Robert Pringle Stuart exposed Norfolk Island’s scarcity and poor quality of food, inadequacy of housing, horrors of torture, and incessant flogging, insubordination of convicts, and corruption of overseers. Bishop Robert Willson later visited Norfolk Island and reported similar findings to the House of Lords, who came to realize the enormity of atrocities perpetrated under the British flag and attempted to remedy the evils. Rumors of resumed atrocities brought Willson back in 1852 and produced a further damning report.

Only a handful of convicts left any written record of such conditions, their descriptions of living and working conditions, food and housing, and, in particular, the punishments given for seemingly trivial offenses are unremittingly horrifying, describing a settlement devoid of all human decency, under the iron rule of the tyrannical autocratic commandants.

The second resurgence of Norfolk Island as a penal settlement began to be wound down by the British Government after 1847, and the last convicts were transported to Tasmania in May 1855.

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by the British for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to discover Tasmania. He named the island in honor of Anthony van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East India Company, who had sent Tasman on his voyage of discovery in 1642. In 1803, the island was colonized by the British Empire as a penal colony with the name Van Diemen's Land.

From the 1830s to the abolition of penal transportation in 1853, Van Diemen's Land was the primary penal colony in Australia. Following the suspension of transportation to Norfolk Island, all convicts sent to Australia served their sentences as assigned labor to free settlers, or in chain gangs assigned to public works. Only the most difficult convicts were sent to the Tasman Peninsula prison known as Port Arthur. In total, some 75,000 convicts were transported to Van Diemen's Land, or about 40 percent of all convicts sent to Australia.

Convicts completing their sentences or earning their tickets-of-leave often promptly left Van Diemen's Land to settle in the new free colony of Victoria. Tensions often ran high between the free settlers and the "Vandemonians" as they were termed, particularly during the Victorian Gold Rush when a flood of settlers from Van Diemen's Land rushed to the Victorian gold fields. Complaints from Victorians about recently released convicts from Van Diemen's Land re-offending in Victoria was one of the contributing reasons for the eventual abolition of transportation to Van Diemen's Land in 1853.

In order to remove the unsavory connotations with crime associated with its name, in 1856 Van Diemen's Land was renamed Tasmania in honor of Abel Tasman. The last penal settlement in Tasmania at Port Arthur finally closed in 1877.

India

The British Empire also established various penal colonies in colonial India. Two of the most infamous were located on the Andaman Islands, comprised of multiple settlements, and at Hijli.

Andaman Islands

British accounts of the Andaman Islands often leave the impression that the island settlements were models of progressive penal reform and were focused predominately around farm labor. Though few supervisors were appointed, total island population numbered more than 10,000. The education of school-aged children of prisoners was compulsory, and all convicts were given free medical attention at one of the four island hospitals. The settlement boasted a safe harbor and high success rate, turning long-sentence convicts into self-respecting men and women.

Indian accounts, however, paint a contrasting picture. From the time of its development in 1858, the settlement was first and foremost a repository for political prisoners. The Cellular Jail at Port Blair included 698 cells designed for solitary confinement. The Viper Chain Gang Jail on Viper Island was reserved for the worst of criminals and was also the site of prisoner hangings. In the twentieth century, it became a convenient place to house prominent members of India's independence movement, and it was here that on December 30, 1943, during Japanese occupation that the first flag of Indian independence was raised.

At the close of the Second World War, the British government announced its intention to abolish the penal settlement and proposed the employment of former inmates in an initiative to develop the island's fisheries, timber, and agricultural resources. In exchange, inmates would be granted return passage to the Indian mainland, or the right to settle on the islands. The penal colony was eventually closed on August 15, 1947, when India gained its independence. It has since served as a museum to the independence movement.

Hijli

Hijli Detention Camp, located in the district of Midnapore West Bengal, was significant in the struggle against the British Raj in the early twentieth century. Because the large numbers of Indian nationalists who participated in the armed struggle against the early British occupation could not be accommodated in ordinary jails, the British Government decided to establish a system of detention camps.

The first, located in Buxa Fort was quickly followed by the 1930 creation of the Hijli Detention Camp. A significant moment in the struggle against British rule occurred at the Hijli Detention Camp on September 16, 1931, when two unarmed detainees were shot dead by the British Police. National leaders were enraged and voiced strong protests against the British Raj over this incident. The Hijli Detention Camp was closed in 1937, but reopened again in 1940. Two years later the camp was officially closed and all detainees were transferred elsewhere.

In May 1950, the first Indian Institute of Technology was housed at the original site of the detention camp. In 1990, former buildings were converted to house the Nehru Museum of Science and Technology.

France

The French Empire also sent criminals to tropical penal settlements. Devil's Island in French Guiana, lasting 1852-1939, received forgers and other criminals. New Caledonia in South Sea Melanesia received dissident rebels as well as convicted criminals.

Devil's Island

Devil’s Island is the smallest of three islands located off the coast of French Guiana and held a notorious French penal colony until 1946. The penitentiary atop the rocky, palm-covered island was first opened by Emperor Napoleon III of France in 1852 and quickly became one of the most infamous prisons in history. In addition to the prison on the island, prison facilities were located on the French mainland at Kourou.

Used by France from 1852 to 1946, the inmates ranged from political prisoners to the most hardened of thieves and murderers. Many of the 80,000 prisoners that faced the harsh conditions at the disease-infested island were never seen again. Escape options, other than by sea, included travel through a dense jungle, and very few convicts managed to escape. A limited number of convicted women were also sent to French Guiana, with instructions to marry the freed male inmates. However the results of this idea were poor and the government ceased the practice in 1907.

The horrors of the penal settlement became notorious in 1895 with the publicity surrounding the experience of French army captain Alfred Dreyfus who had been wrongfully convicted of treason and was sent to Devil’s Island.

In 1938, the French government stopped sending prisoners to Devil's Island, and in 1952 the prison closed permanently. Most of the prisoners returned to mainland France, though some chose to remain in French Guiana.

Several movies, songs, a stage play, as well as a number of books have featured Devil's Island. The most famous is a 1970 best-selling book, also made into a popular movie, entitled Papillon by former Devil's Island convict Henri Charriere, which tells of his numerous alleged escape attempts.

New Caledonia

The island of New Caledonia was made a French possession in 1853, in an attempt by Napoleon III to rival the British colonies in Australia and New Zealand. Between 1854 and 1922 France sent a total of 22,000 convicted felons to penal colonies along the south-west coast of the island; this number includes regular criminals as well as political prisoners such as Parisian socialists and Kabyle nationalists. Towards the end of the penal colony era, free European settlers (including former convicts) and Asian contract workers by far out-numbered the population of forced workers. The indigenous Kanak populations declined drastically in that same period due to introduced diseases and an apartheid-like system called Code de l'Indigénat, which imposed severe restrictions on their livelihood, freedom of movement, and land ownership.

Russia

Both Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union used Siberia as a penal colony for criminals and public dissidents. Though geographically contiguous with mainland Russia, Siberia provided both remoteness and a harsh climate for the worst of society’s prisoners. Penal systems like the Gulag and its tsarist predecessor, the katorga, provided penal labor to develop forestry, logging, and mining industries, construction enterprises, and highway and railroad construction across Siberia.

Katorga

The katorga was a seventeenth century system of penal servitude of the prison farm type used in Imperial Russia. Prisoners were sent to remote camps in vast uninhabited areas of Siberia, where volunteer laborers were unavailable, and forced to perform hard manual labor. Unlike concentration camps, a katorga was within the normal judicial system of Imperial Russia, though both share the same main features of confinement, simplified facilities, and forced labor usually involving hard, unskilled, or semi-skilled work. The most common occupations in katorga camps were mining and timber works.

Katorgas were established in the seventeenth century in under populated areas of Siberia and the Russian Far East. Nonetheless, a few prisoners successfully escaped back to populated areas. Since the seventeenth century, Siberia gained its fearful connotation of punishment, which was further enhanced by the Soviet Union’s Gulag system that developed after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

After a change in Russian penal law in 1847, exile and katorga became common penalties to the participants of national uprisings within the Russian Empire. This led to an increasing number of Polish people being sent to Siberia to perform labor under katorga systems. They were known as "Sybiraks," some of them remaining there after their sentences to form a Polish minority in Siberia.

Anton Chekhov, the famous Russian writer and playwright, visited the katorga settlements of Russia’s Far East Sakhalin island in 1891. Writing about the conditions, he criticized the shortsightedness and incompetence of the officials in charge that allowed for conditions of poor living standards, waste of government funds, and low productivity. After the Russian Revolution, Russia’s penal system was taken over by the Bolsheviks, eventually transforming them into Gulag labor camps.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Belbenoit, René. Hell on Trial. Translated from the Original French Manuscript by Preston Rambo. E. P Dutton & Co. Reprint by Blue Ribbon Books, New York, 1941.

- Belbenoit, René. 1938. Dry guillotine: Fifteen years among the living dead. Reprint: Berkley, 1975. ISBN 0425029506

- Charrière, Henri. Papillon. Perennial, 2001. ISBN 978-0060934798

- Kropotkin, P. In Russian and French Prisons. London: Ward and Downey, 1887.

External Links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

- In Russian and French Prisons by P.Kropotkin.

- The Labor of Doing Time by Julie Browne.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Penal_colony history

- Andaman_Islands history

- Hijli_Detention_Camp history

- Devil's_Island history

- Katorga history

- Norfolk_Island history

- Van_Diemen's_Land history

- Chain_gang history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.