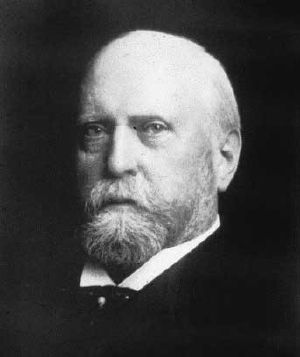

Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 - March 18, 1899) was one of the pre-eminent paleontologists of the 19th century, who discovered and named many fossils found in the American West.

Marsh was born in Lockport, New York. He graduated at Yale College in 1860, and studied geology and mineralogy in the Sheffield Scientific School, New Haven, and afterwards paleontology and anatomy in Berlin, Heidelberg and Breslau. He returned to the United States in 1866 and was appointed professor of vertebrate paleontology at Yale University. He persuaded his uncle, George Peabody, to establish the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale.

In May 1871 Marsh found the first American pterosaur fossils. He also discovered the remains of early horses. Marsh described the remains of Cretaceous toothed birds (such as Ichthyornis and Hesperornis) and flying reptiles, and Cretaceous and Jurassic dinosaurs, including Apatosaurus and Allosaurus.

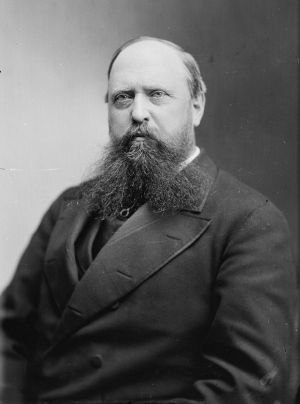

Marsh is famous for his "palaeontological battle", the so-called Bone Wars, with Edward Drinker Cope during the late 19th century. The two men were fierce rivals in the discovery of palaeontological specimens, discovering and describing over 120 new species of dinosaur between them.

Marsh died in 1899 and was interred at the Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut.

Bone Wars

The Bone Wars were an infamous period in the history of paleontology when the two pre-eminent paleontologists of the time, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, competed to see who could find the most, and more sensational, new species of dinosaur. This competition was marred by bribery, politics, violations of American Indian territories and virulent personal attacks.

History

| “ | These strange creatures flapped their leathery wings over the waves, and often plunging, seized many an unsuspecting fish; or, soaring, at a safe distance, viewed the sports and combats of more powerful saurians of the sea. At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore, and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs. | ” |

—Cope, describing the Pterodactyl | ||

The Bone Wars were triggered by the 1858 discovery of the holotype specimen of Hadrosaurus foulkii by William Parker Foulke in the marl pits of Haddonfield, New Jersey. It was the first nearly-complete skeleton of a dinosaur ever found, and sparked great interest in the new field of paleontology. The skeleton was sent to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, where it was named and described in 1858 by Joseph Leidy, who was perhaps the leading paleontologist of the time.

Cope worked for Leidy, and soon was working in the marl pits of southwest New Jersey. Together they made a number of discoveries, including the second almost-complete skeleton of a dinosaur, a carnivorous Dryptosaurus aquilunguis. They made arrangements for the companies digging up the marl, which was being used as a fertilizer, to contact them whenever any fossilized bones were unearthed. Cope moved to Haddonfield to be near the discoveries, and soon rivaled his mentor in fame.

At the time, Marsh was a professor at Yale University (which was still called Yale College), in New Haven, Connecticut, studying fossilized dinosaur tracks in the Connecticut Valley. As the first American professor of paleontology, the discoveries in New Jersey were of intense interest. He visited Cope, whom he knew from the University of Berlin, and was given a tour of the discovery sites. Together they unearthed some new partial skeletons, but the rivalry started soon after when Cope learned that Marsh had secretly returned and bribed the marl company managers to report any new finds directly to him.[1]

In 1870, the attention shifted west to the Morrison Formation in Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado, which during the Cretaceous was on the shore of a great sea. Since both were wealthy — Cope was the scion of a wealthy Quaker family, and Marsh was the nephew of George Peabody, for whom Yale's museum is named — they used their own personal wealth to fund expeditions each summer, and then spent the winter publishing their discoveries. Small armies of fossil hunters in mule-drawn wagons were soon sending quite literally tons of fossils back East.

But their discoveries were accompanied by sensational accusations of spying, stealing workers, stealing fossils, and bribery. Among other things Cope repeatedly accused Marsh of stealing fossils, and was so angry that he stole a train full of Marsh's fossils, and had it sent to Philadelphia. Marsh, in turn, was so determined that he stole skulls from American Indian burial platforms and violated treaties by trespassing on their land. He was also so protective of his fossil sites that he even used dynamite on one to prevent it from falling into Cope's hands.

They also tried to ruin each other's professional credibility. When Cope made a simple error, and attached the head of an Elasmosaurus to the wrong end of the animal (the tail, instead of the neck), he tried to cover up his mistake. He even went so far as to purchase every copy he could find of the journal it was published in; but Marsh, who pointed out the error in the first place, made sure to publicize the story. Marsh was no more infallible, however. He made a similar error, and put the wrong head on the skeleton of an Apatosaurus (which was still being called the Brontosaurus). But his error was not discovered for more than a hundred years. In 1981, the Peabody Museum finally acknowledged the mistake, and exhibits around the world had to be redone.

Legacy

By most standards, Marsh won the Bone Wars. Both made finds of incredible scientific value, but while Marsh discovered a total of 86 new species, due in part to his discovery of the Como Bluff site, near Medicine Bow, Wyoming (one of the richest source of fossils known); Cope only discovered 56. Many of the fossils Cope unearthed were of species that had already been named, or were of uncertain origin. And while the species Marsh discovered include household names, like the Triceratops, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus, even Cope's most famous discoveries, like the Dimetrodon, Camarasaurus, Coelophysis, and Monoclonius were more obscure. But their cumulative finds defined the field of paleontology; at the start of the Bone Wars, there were only nine named species of dinosaur in North America; after the Bone Wars, there were around 150 species. Furthermore, some of their theories — like Marsh's argument that birds are descended from dinosaurs; or "Cope's law", which states that over time species tend to get larger — are still referred to today.

Cope is widely regarded as the more brilliant scientist, but more brash and careless. He was so prolific, publishing more than 1,200 scientific papers, that he set a record he still holds to this day. Marsh in turn was colder and more methodical but he was the better politician. He moved easily among the members of high society, including President Ulysses S. Grant and the Rothschilds. He even befriended Buffalo Bill Cody and the Lakota Indian chief Red Cloud.

Their rivalry lasted until Cope's death in 1897, but by that time they had both run out of money. Marsh got Cope's federal funding cut off (including his funding from the U.S. Geological Survey), and Cope had to sell part of his collection. Marsh in turn had to mortgage his home, and ask Yale for a salary to live on. Cope nonetheless issued a final challenge at his death; he had his skull donated to science so that his brain could be measured, hoping that his brain would be larger than his adversary; at the time, it was thought brain size was the true measure of intelligence. Marsh never rose to the challenge, but Cope's skull is still preserved.[1]

While their collective discoveries helped define the budding new field of study, the race also had some negative effects. Their animosity and public behavior harmed the reputation of American paleontology in Europe for decades. Furthermore, the use of dynamite and sabotage by employees of both men destroyed hundreds of potentially critical fossil remains. It will never be known how much their rivalry has damaged our understanding of life forms in the regions which they worked.

Recently the Bone Wars has been the subject of a graphic novel, Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards, by Joe Ottoviani.

External links

- Illustrated article on the Bone Wars.

- Another article on the Bone Wars.

- Article on the Haddonfield, NJ site.

- The Bone Cabin, build entirely from fossilized bones recovered from the Como Bluff site.

- {{{2}}} at the Open Directory Project

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

- Othniel Charles Marsh (1832-1899). University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899). Lefalophodon. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.