Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths (Latin: Ostrogothi or Austrogothi) were a branch of the Goths, an East Germanic tribe that played a major role in the political events of the late Roman Empire. The other branch was the Visigoths.

The Ostrogoths established a relatively short-lived successor state of Rome in Italy and the Pannonia, even briefly incorporating most of Hispania and southern Gaul. They reached their zenith under their Romanised king Theodoric the Great, who patronized such late Roman figures as Boethius and Cassiodorus, in the first quarter of the sixth century. By mid-century, however, they had been conquered by Rome in the Gothic War (535–554), a war with devastating consequences for Italy. The Ostrogoths are an example of a people who were a significant presence on the stage of history for several centuries but who did not establish an enduring political entity bearing their name or become the dominant people of a specific territory. Rather, their identity became assimilated into that of the various places where they eventually settled. This process is part of the story of human development. They walked across the stage of history and, while they did not stay on that stage, they were a significant factor for some time in the affairs of Europe at a critical time in its story as the old order of the Roman Empire gave way to the new order in which their political successors, the Franks, together with the Pope, formed the Holy Roman Empire and gave birth to the socio-religious-political concept of Christendom.

Divided Goths: Greuthungi and Ostrogothi

The division of the Goths is first attested in 291.[1] The Tervingi are first attested around that date, the Greuthungi, Vesi, and Ostrogothi are all attested no earlier than 388.[1] The Greuthungi are first named by Ammianus Marcellinus, writing no earlier than 392 and perhaps later than 395, and basing his account of the words of a Tervingian chieftain who is attested as early as 376.[1] The Ostrogoths are first named in a document dated September 392 from Milan.[1] Claudian mentions that they together with the Gruthungi inhabit Phrygia.[2] According to Herwig Wolfram, the primary sources either use the terminology of Tervingi/Greuthungi or Vesi/Ostrogothi and never mix the pairs.[1] All four names were used together, but the pairing was always preserved, as in Gruthungi, Austrogothi, Tervingi, Visi.[3] That the Tervingi were the Vesi/Visigothi and the Greuthungi the Ostrogothi is also supported by Jordanes.[4] He identified the Visigothic kings from Alaric I to Alaric II as the heirs of the fourth-century Tervingian king Athanaric and the Ostrogothic kings from Theodoric the Great to Theodahad as the heirs of the Greuthungian king Ermanaric. This interpretation, however, though very common among scholars today, is not universal. According to the Jordanes' Getica, around 400 the Ostrogoths were ruled by Ostrogotha and derived their name from this "father of the Ostrogoths," but modern historians often assume the converse, that Ostrogotha was named after the people.[1]

Both Herwig Wolfram and Thomas Burns conclude that the terms Tervingi and Greuthungi were geographical identifiers used by each tribe to describe the other.[3][5] This terminology therefore dropped out of use after the Goths were displaced by the Hunnic invasions. In support of this, Wolfram cites Zosimus as referring to a group of "Scythians" north of the Danube who were called "Greuthungi" by the barbarians north of the Ister.[6] Wolfram concludes that this people was the Tervingi who had remained behind after the Hunnic conquest.[6] He further believes that the terms "Vesi" and "Ostrogothi" were used by the peoples to boastfully describe themselves.[3] On this understanding, the Greuthungi and Ostrogothi were more or less the same people.[5]

The nomenclature of Greuthungi and Tervingi fell out of use shortly after 400.[1] In general, the terminology of a divided Gothic people disappeared gradually after they entered the Roman Empire.[3] The term "Visigoth," however, was an invention of the sixth century. Cassiodorus, a Roman in the service of Theodoric the Great, invented the term "Visigothi" to match that of "Ostrogothi," which terms he thought of as "western Goths" and "eastern Goths" respectively.[3] The western-eastern division was a simplification and a literary device of sixth-century historians where political realities were more complex.[7] Furthermore, Cassiodorus used the term "Goths" to refer only to the Ostrogoths, whom he served, and reserved the geographical term "Visigoths" for the Gallo-Spanish Goths. This usage, however, was adopted by the Visigoths themselves in their communications with the Byzantine Empire and was in use in the seventh century.[7]

Other names for the Goths abounded. A "Germanic" Byzantine or Italian author referred to one of the two peoples as the Valagothi,, meaning "Roman Goths."[7] In 484 the Ostrogoths had been called the Valameriaci (men of Valamir) because they followed Theodoric, a descendant of Valamir.[7] This terminology survived in the Byzantine East as late as the reign of Athalaric, who was called του Ουαλεμεριακου (tou Oualemeriakou) by John Malalas.[8]

Etymology of Greuthungi and Ostrogothi

"Greuthungi" may mean "steppe dwellers" or "people of the pebbly coasts."[3] The root greut- is probably related to the Old English greot, meaning "flat."[9] This is supported by evidence that geographic descriptors were commonly used to distinguish people living north of the Black Sea both before and after Gothic settlement there and by the lack of evidence for an earlier date for the name pair Tervingi-Greuthungi than the late third century.[10] That the name "Greuthungi" has pre-Pontic, possibly Scandinavian, origins still has support today.[10] It may mean "rock people," to distinguish the Ostrogoths from the Gauts (in what is today Sweden).[10] Jordanes does refer to an Evagreotingi (Greuthung island) in Scandza, but this may be legend. It has also been suggested that it may be related to certain place names in Poland, but this has met with little support.[10]

"Ostrogothi" means "Goths of (or glorified by) the rising sun."[3] This has been interpreted as "gleaming Goths" or "east Goths."

Prehistory

The Goths were a single nation mentioned in several sources up to the 3rd century when they apparently split into at least two groups, the Greuthungi in the east and Tervingi in the west.[9] Both tribes shared many aspects, especially recognizing a patron deity that the Romans named Mars. This so-called "split" or, more appropriately, resettlement of western tribes into the Roman province of Dacia was a natural result of population saturation of the area north of the Black Sea. The Goths there established a vast and powerful kingdom, during the 3rd and 4th centuries, between the Danube and the Dniepr in what is now Romania, Moldavia and western Ukraine (see Chernyakhov culture; Gothic runic inscriptions).[11] This was a multi-tribal state ruled by a Gothic elite but inhabited by many other interelated but multi-tongue tribes including the Iranian speaking Sarmatians, the Germanic speaking Gepids, the Thracian speaking Dacians, other minor Celtic and Thracian tribes and possibly early Slavs.[12]

History

Hunnic invasions

The rise of the Huns around 370 overwhelmed the Gothic kingdoms.[13] Many of the Goths migrated into Roman territory in the Balkans, while others remained north of the Danube under Hunnic rule.[14] They became one of the many Hunnic vassals fighting in Europe, as in the Battle of Chalons in 451. Several uprisings against the Huns were suppressed. The collapse of Hunnic power in the 450s led to further violent upheaval in the lands north of the Danube, during which most of the Goths resident in the area migrated to the Balkans. It was this group that became known as the Ostrogoths.

Gothic was still spoken sporadically in Crimea as late as the 16th century: the Crimean Gothic language.

Post-Hunnic movements

Their recorded history begins with their independence from the remains of the Hunnic Empire following the death of Attila the Hun in 453. Allied with the former vassal and rival, the Gepids and the Ostrogoths led by Theodemir broke the Hunnic power of Attila's sons in the Battle of Nedao in 454.[15]

The Ostrogoths now entered into relations with the Empire, and were settled on lands in Pannonia.[16] During the greater part of the latter half of the 5th century, the East Goths played in south-eastern Europe nearly the same part that the West Goths played in the century before. They were seen going to and fro, in every conceivable relation of friendship and enmity with the Eastern Roman power, until, just as the West Goths had done before them, they passed from the East to the West.

Kingdom in Italy

The greatest of all Ostrogothic rulers, the future Theodoric the Great (whose name means "leader of the people") of Ostrogothic Kingdom, was born to Theodemir in or about 454, soon after the Battle of Nedao. His childhood was spent at Constantinople as a diplomatic hostage, where he was carefully educated. The early part of his life was taken up with various disputes, intrigues and wars within the Byzantine empire, in which he had as his rival Theodoric Strabo, a distant relative of Theodoric the Great and son of Triarius. This older but lesser Theodoric seems to have been the chief, not the king, of that branch of the Ostrogoths which had settled within the Empire at an earlier time. Theodoric the Great, as he is sometimes distinguished, was sometimes the friend, sometimes the enemy, of the Empire. In the former case he was clothed with various Roman titles and offices, as patrician and consul; but in all cases alike he remained the national Ostrogothic king. Theodoric is also known for his attainment of support from the Catholic church, which he gained by appeasing the pope in 520. During his reign, Theodoric, who was Arian, allowed “freedom of religion” which had not been done before. However, he did try to appease the pope and tried to keep his allies with the church strong. He saw the pope as an authority not only in the church but also over Rome.

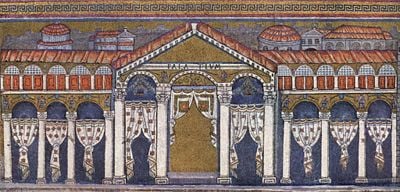

Theodoric sought to revive Roman culture and government and in doing so, profit the Italian people.[17] It was in both characters together that he set out in 488, by commission from the Byzantine emperor Zeno, to recover Italy from Odoacer.[18] By 493 Ravenna was taken, where Theodoric would set up his capital. It was also at this time that Odoacer was killed by Theodoric's own hand. Ostrogothic power was fully established over Italy, Sicily, Dalmatia and the lands to the north of Italy. In this war there is some evidence that the Ostrogoths and Visigoths began again to unite if it is true that Theodoric was helped by Visigothic auxiliaries. The two branches of the nation were soon brought much more closely together; after he was forced to become regent of the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse, the power of Theodoric was practically extended over a large part of Gaul and over nearly the whole of the Iberian peninsula. Theodoric also attempted to forge an alliance with the Frankish and Burgundian kingdoms by means of a series of diplomatic marriages. This strengthening of power eventually led the Byzantine emperor to fear that Theodoric would become too strong, and motivated his subsequent alliance with the Frankish king, Clovis I, to counter and ultimately overthrow the Ostrogoths.

A time of confusion followed the death of Alaric II, the son-in-law of Theodoric, at the Battle of Vouillé. The Ostrogothic king stepped in as the guardian of his grandson Amalaric, and preserved for him all his Iberian and a fragment of his Gaul dominion.[19] Toulouse passed to the Franks but the Goth kept Narbonne and its district and Septimania, which was the last part of Gaul held by the Goths and kept the name of Gothia for many ages. While Theodoric lived, the Visigothic kingdom was practically united to his own dominion. He seems also to have claimed a kind of protectorate over the Germanic powers generally, and indeed to have practically exercised it, except in the case of the Franks.

The Ostrogothic dominion was now again as great in extent as and far more splendid than it could have been in the time of Hermanaric; however it was now of a wholly different character. The dominion of Theodoric was not a barbarian but a civilized power. His twofold position ran through everything. He was at once national king of the Goths, and successor, though without any imperial titles, of the West Roman emperors. The two nations, differing in manners, language and religion, lived side by side on the soil of Italy; each was ruled according to its own law, by the prince who was, in his two separate characters, the common sovereign of both. It is believed that between 200,000 to 250,000 Ostrogoths settled in Italy but these are guesses and the numbers may have been much lower or higher.

The picture of Theodoric's rule is drawn for us in the state papers drawn up, in his name and in the names of his successors, by his Roman minister Cassiodorus. The Goths seem to have been thick on the ground in northern Italy; in the south they formed little more than garrisons. In Theodoric's theory the Goth was the armed protector of the peaceful Roman; the Gothic king had the toil of government, while the Roman consul had the honor. All the forms of the Roman administration went on, and the Roman policy and culture had great influence on the Goths themselves. The rule of the prince over distinct nations in the same land was necessarily despotic; the old Germanic freedom was necessarily lost. Such a system needed a Theodoric to carry it on. It broke in pieces after his death.

War with Rome (535–554)

On the death of Theodoric in 526 the Ostrogoths and Visigoths were again separated. The few instances in which they are found acting together after this time are as scattered and incidental as they were before. Amalaric succeeded to the Visigothic kingdom in Iberia and Septimania. Provence was added to the dominion of the new Ostrogothic king Athalaric, the grandson of Theodoric through his daughter Amalasuntha.[20] Both were unable to settle disputes among Gothic elites. Theodahad, cousin of Amalasuntha and nephew of Theodoric through his sister, took over and slew them; however the usurping ushered in more bloodshed. Three more rulers stepped in during the next five years.

The weakness of the Ostrogothic position in Italy now showed itself. Byzantine emperor Justinian I had always strived to restore as much of the West Roman Empire as he could and certainly would not pass up the opportunity. In 535, he commissioned Belisarius to attack the Ostrogoths. Belisarius quickly captured Sicily and then crossed into Italy where he captured Naples and Rome in 536 and then marched north, taking Mediolanum (Milan) and the Ostrogoth capital of Ravenna in 540.[21]

At this point Justinian offered the Goths a generous settlement—too generous by far in Belisarius' eyes—the right to keep an independent kingdom in the Northwest of Italy, and the demand that they merely give half of all their treasure to the empire. Belisarius conveyed the message to the Goths, although he himself withheld from endorsing it. They, on the other hand felt there must be a snare somewhere. The Goths did not trust Justinian, but because Belisarius had been so well-mannered in his conquest they trusted him a little more, and agreed to take the settlement only if Belisarius endorsed it. This condition made for something of an impasse.

A faction of the Gothic nobility pointed out that their own king Witiges, who had just lost, was something of a weakling and they would need a new one.[22] Eraric, the leader of the group, endorsed Belisarius and the rest of the kingdom agreed, so they offered him their crown. Belisarius was a soldier, not a statesman, and still loyal to Justinian. He made as if to accept the offer, rode to Ravenna to be crowned, and promptly arrested the leaders of the Goths and reclaimed their entire kingdom—no halfway settlements—for Byzantium.

This upset Justinian greatly: the Persians had been attacking in the east, and he wanted a stable neutral country separating his western border from the Franks, who weren't so friendly. Belisarius was sent to face the Persians and therefore left John, a Byzantine officer, to govern Italy temporarily.

In 545 Belisarius then returned to Italy, where he found the situation had changed greatly.[23] Eraric was slain and the pro-Roman faction of Gothic elite had been toppled. In 541 the Ostrogoths had elected a new leader Totila; this Goth nationalist and brilliant commander had recaptured all of northern Italy and even driven the Byzantines out of Rome. Belisarius took the offensive, tricked Totila into yielding Rome along the way, but then lost it again after a jealous Justinian, fearful of Belisarius' power, starved him of supplies and reinforcements. Belisarius was forced to go on the defensive, and in 548, Justinian relieved him in favor of the eunuch general Narses, of whom he was more trustful.

Totila was slain in the Battle of Taginae in July 552[24] and his followers Teia,[25] Aligern, Scipuar, and Gibal were all killed or surrendered in the Battle of Mons Lactarius in October 552 or 553. Widin, the last attested member of the Gothic army revolted in late 550s, with minimal military help from the Franks. His uprising was fruitless; the revolt ended with Widin captured and brought to Constantinople for punishment in 561 or 562.[26]

With that final defeat, the Ostrogothic name wholly died. The nation had practically evaporated with Theodoric's death.[27] "The leadership of western Europe therefore passed by default to the Franks. Consequently, Ostrogothic failure and Frankish success were crucial for the development of early medieval Europe," for Theodoric had made it "his intention to restore the vigor of Roman government and Roman culture."[28] The chance of forming a national state in Italy by the union of Roman and Germanic elements, such as those which arose in Gaul, in Iberia, and in parts of Italy under Lombard rule, was thus lost. As a result the Goths hold a different place in Iberian memory from that which they hold in Italian memory: In Italy the Goth was but a momentary invader and ruler, while in Iberia the Goth supplies an important element in the modern nation. That element has been neither forgotten nor despised. Part of the unconquered region of northern Iberia, the land of Asturias, kept for a while the name of Gothia, as did the Gothic possessions in Gaul.

Legacy of Ostrogothic culture

Of Gothic literature in the Gothic language exists the Bible of Ulfilas and some other religious writings and fragments. Of Gothic legislation in Latin we have the edict of Theodoric of the year 500, and the Variae of Cassiodorus may pass as a collection of the state papers of Theodoric and his immediate successors. Among the Visigothic written laws had already been put forth by Euric. Alaric II put forth a Breviarium of Roman law for his Roman subjects; but the great collection of Visigothic laws dates from the later days of the monarchy, being put forth by King Reccaswinth about 654. This code gave occasion to some well-known comments by Montesquieu and Gibbon, and has been discussed by Savigny (Geschichte des romischen Rechts, ii. 65) and various other writers. They are printed in the Monumenta Germaniae, leges, tome i. (1902).

Of special Gothic histories, besides that of Jordanes, already so often quoted, there is the Gothic history of Isidore, archbishop of Seville, a special source of the history of the Visigothic kings down to Suinthila (621-631). But all the Latin and Greek writers contemporary with the days of Gothic predominance make their constant contributions. Not for special facts, but for a general estimate, no writer is more instructive than Salvian of Marseilles in the 5th century, whose work, De Gubernatione Dei, is full of passages contrasting the vices of the Romans with the virtues of the "barbarians," especially of the Goths. In all such pictures we must allow a good deal for exaggeration both ways, but there must be a groundwork of truth. The chief virtues that the Roman Catholic presbyter praises in the Arian Goths are their chastity, their piety according to their own creed, their tolerance towards the Catholics under their rule, and their general good treatment of their Roman subjects. He even ventures to hope that such good people may be saved, not withstanding their heresy. This image must have had some basis in truth, but it is not very surprising that the later Visigoths of Iberia had fallen away from Salvian's somewhat idealistic picture.

Ostrogothic rulers

Amal Dynasty

- Valamir (not yet in Italy)

- Theodemir (not yet in Italy)

- Theodoric the Great 493–526

- Athalaric 526–534

- Theodahad 534–536

Later kings

- Witiges 536–540

- Ildibad 540–541

- Eraric 541

- Baduela 541–552 (also known as Totila)

- Theia 552–553 (also known as Teiam or Teja)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Herwig Wolfram. History of the Goths, trans. Thomas J. Dunlap (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 24.

- ↑ Wolfram, 387 n52.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Wolfram, 25.

- ↑ Peter Heather. The Goths. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 52–57, 300–301.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Thomas S. Burns, A History of the Ostrogoths (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 44.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wolfram, 387 n57.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Wolfram, 26.

- ↑ Wolfram, 389 n67.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Burns, 30.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Wolfram, 387–388 n58.

- ↑ Burns, 110-112.

- ↑ Burns, 108-112.

- ↑ Burns, 37.

- ↑ Burns, 38.

- ↑ Burns, 46.

- ↑ Burns, 52-53.

- ↑ Norman F. Cantor. The Civilization of the Middle Ages. (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994), 109.

- ↑ Burns, 77.

- ↑ Burns, 98.

- ↑ Burns, 93.

- ↑ Burns, 185.

- ↑ Burns, 199.

- ↑ Burns, 204.

- ↑ Burns, 217.

- ↑ Burns, 214.

- ↑ Burns, 215.

- ↑ Burns, 219.

- ↑ Cantor, 105–107.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amory, Patrick. People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489–554. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521526353

- Burns, Thomas S. A History of the Ostrogoths. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984. ISBN 0253328314

- Cantor, Norman F. The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994. ISBN 0060925531

- Heather, Peter. The Goths. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

- Heather, Peter. "Theoderic, king of the Goths." Early Medieval Europe 4 (2) (September 1995): 145–173.

- Jordanes. 'The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, Translated by Charles Christopher Mierow. original 1915. Evolution Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1889758779 In English Version with an Introduction and a Commentary. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- Wallace-Hadrill, John Michael. The Barbarian West, 400–1000, 3rd ed. London: Hutchison, 1967. ISBN 0090212533

- Wolfram, Herwig. History of the Goths, Translated by Thomas J. Dunlap. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0520069838

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Western and Central Europe Encyclopedia Chonology: Ostrogoths

- Succesors of Rome: Germania, 395-774

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Ostrogoths

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.