Difference between revisions of "National Association for the Advancement of Colored People" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) (copied from wikipedia) |

|||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Sociology]] | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

| − | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Copyedited}} | |

| − | [[ | + | [[File:President John F. Kennedy Meets with National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Group.jpg|thumb|350px|NAACP representatives E. Franklin Jackson and Stephen Gill Spottswood meeting with [[John F. Kennedy|President Kennedy]] at the White House in 1961]] |

| − | The '''National Association for the Advancement of Colored People''' | + | The '''National Association for the Advancement of Colored People,''' also known as the '''NAACP,''' is one of the oldest and most influential civil rights organizations in the [[United States]]. Founded on February 12, 1909, the Association was created to work toward the betterment and advancement of black Americans nationwide. Members often refer to the organization as The National Association, in reference to the association’s pre-eminence among similar organizations active in the struggle for civil rights and equality in the early twentieth century. Its title, retained in accord with tradition, represents one of the last surviving usages of the term "colored people." Although this term generally became viewed as dated and derogatory, in the historical context of the NAACP the term is considered inoffensive. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The history of the NAACP includes significant victories, notably in ending [[racial segregation]] in [[education]], in bringing public attention to [[lynching]]s of black Americans, and in successful voter registration of black Americans and their subsequent voting in elections. The NAACP, however, has also experienced many internal struggles concerning its methods in achieving equality of rights. Such difficulties were evident in its beginnings when [[W.E.B. Du Bois]] clashed with others over the involvement of white leadership, through its loss of influence in the [[American Civil Rights Movement]] to other organizations and civil rights leaders, and continued in more recent times with financial difficulties including mismanagement of funds by the leadership. Nevertheless, the NAACP emerged into the twenty-first century complete with a vision of racial equality in American society, and the determination and resources to work towards it. Until such time as [[racism]], both in thought and action, is completely overcome and all people are considered part of the same human family, there is work to be done and the NAACP is ready to do it. | ||

==Organization== | ==Organization== | ||

| − | The NAACP's headquarters are in | + | The NAACP's headquarters are located in Baltimore, Maryland, with additional regional offices located in California, New York, Michigan, Missouri, Georgia, and Texas. Each incorporates local youth and college chapters to organize local community activities for individual members. As of 2004, the NAACP had approximately 500,000 members. |

| − | The NAACP is run nationally by a 64-member board of directors led by a chairman. The board | + | The NAACP is run nationally by a 64-member board of directors led by a chairman. The board is responsible for electing one president and one chief executive officer for the national organization. |

| − | + | The NAACP is divided into various departments and divisions which serve to direct the Association at specific levels. The Association’s Branch and Field Services Department and the Youth and College Department support the operations of local NAACP chapters. The NAACP’s Legal Department focuses on minority court cases, often working to regulate systematic discrimination in environments of employment, [[government]], or [[education]]. The Association’s Washington, D.C. Bureau is responsible for the political [[lobbying]] of U.S. Government legislation. The organization’s Education Department works for improvements toward public education at the local, state, and federal levels. The goal of the NAACP Health Division is to advance [[healthcare]] for minorities through public policy initiatives and education. | |

| − | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | In | + | In 1905, a group of thirty-two prominent, outspoken black American men met to discuss the challenges facing "people of color," a term referring to those who did not have white skin or were not of a Caucasian background. The meeting was designed to create potential strategies and solutions for the societal betterment of all colored people throughout the United States. Under the leadership of [[Harvard University]] scholar [[W.E.B. Du Bois]], the meeting took place at [[Niagara Falls]], and as a result the group came to be known as the "Niagara Movement." Due to existing U.S. hotel regulations regarding [[racial segregation]], the meeting took place at a hotel situated across the border in [[Canada]]. One year later, three whites joined the movement, [[social work]]ers [[Mary White Ovington]] and Henry Moskowitz, and [[journalism|journalist]] William E. Walling. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | For a time, the fledgling group struggled with limited resources. To increase its scope and effectiveness, the movement decided to broaden its membership and soon sent solicitations for support to more than sixty prominent Americans of the day. A later meeting, intentionally set to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the birth of United States President [[Abraham Lincoln]], was set for February 12, 1909. Though the actual meeting did not occur until three months later, this date is often cited as the founding date of the national organization. | |

| − | + | On May 30, 1909, the Niagara Movement’s second conference took place in [[New York City]]'s Henry Street [[Settlement House]]. From this meeting, an organization of more than forty like-minded individuals emerged, and was quickly entitled the National Negro Committee. Once again, Du Bois played a key role in organizing the event and presided over the New York proceedings. Also in attendance was African American journalist and anti-lynching crusader [[Ida B. Wells-Barnett]]. | |

| − | + | One year earlier, the Springfield Race Riot of 1908 in Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois, highlighted an urgent need for a large civil rights organization to be formed within the United States. This event is often represented as the spark that initiated the development and formation of the NAACP. | |

| − | + | In May of 1910, the members adopted the name National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The organization was formally incorporated the following year, and delineated its mission as follows: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <Blockquote>To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.</Blockquote> | |

| − | The | + | The 1911 conference resulted in a more viable, influential, and diverse organization, with a leadership that was predominately white and heavily [[Judaism|Jewish]]. At its founding, the NAACP included just one black American on its executive board, Du Bois, and did not elect a black president until 1975. In its early stages, the Jewish community contributed greatly to the organization’s founding and finances. Jewish co-founders included [[Lillian Wald]], Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and Chairman Joel Elias Spingarn, a Professor Emeritus of [[Columbia University]]. |

| − | + | From its foundation in 1909 until 1930, Moorfield Storey served as president of the NAACP. Storey, a Caucasian, was a long-time Democratic liberal who advocated for [[laissez-faire]] free markets, supported the [[gold standard]], and opposed [[imperialism]]. Storey consistently and aggressively championed civil rights not only for blacks but also for [[American Indian]]s and immigrant populations, publicly opposing immigration restrictions. | |

| − | + | As a member of the executive board, conference leader W.E.B Du Bois played a pivotal role in the early operations of the organization, and served as editor of the association's [[magazine]], ''The Crisis'', a publication with a circulation of more than 30,000. | |

| − | + | ==Fighting Jim Crow== | |

| + | [[Image:ColoredDrinking.jpg|thumb|400px|An African American drinks out of a segregated water cooler designated for "colored" patrons in 1939 at a streetcar terminal in Oklahoma City.]] | ||

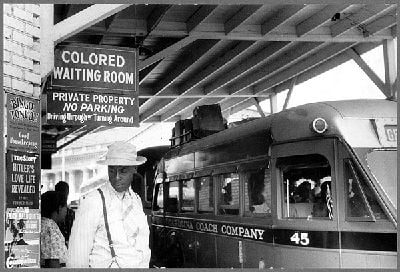

| + | [[File:JimCrowInDurhamNC.jpg|thumb|400px|"At the bus station in Durham, North Carolina", May 1940. Photo by Jack Delano.]] | ||

| + | In its early years, the NAACP concentrated on using the courts to overturn the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow]] statutes that legalized [[racism|racial discrimination]]. In 1913, the association organized opposition to U.S. President [[Woodrow Wilson]]'s introduction of [[racial segregation]] into federal government policy. | ||

| − | + | By 1914, with more than 6,000 members and 50 branches, the organization was influential in winning the right of African-Americans to serve as officers in [[World War I]]. Six hundred African-American officers were commissioned and 700,000 African Americans registered for the [[conscription|draft]]. The following year the NAACP organized a nationwide protest against filmmaker D.W. Griffith's silent film ''Birth of a Nation,'' a film that glamorized the [[Ku Klux Klan]]. | |

| − | + | The NAACP began playing a prominent role in lawsuits targeting racial segregation and other denials of civil liberties. The organization challenged Oklahoma’s discriminatory "grandfather" rule that disenfranchised its state residents, and in 1917 persuaded the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] under ''Buchanan v. Warley'' to deny states and local governments the right to officially segregate black Americans into separate residential districts. | |

| − | The NAACP | ||

| − | + | In 1916, NAACP chairman Joel Spingarn invited James Weldon Johnson to serve as the organization’s field secretary. Through the efforts of Johnson, a former U.S. consul to [[Venezuela]] and noted scholar and columnist, NAACP membership jumped from 9,000 to almost 90,000 within four years. In 1920, Johnson was elected head of the organization. Over the next ten years, the NAACP escalated its lobbying and litigation efforts, becoming internationally known for its advocacy of equal rights and equal protection for the "American Negro." | |

| − | + | Between the First and Second World Wars, the NAACP devoted much of its effort to prevent the [[lynching]] of black Americans throughout the United States. The NAACP worked for more than a decade to obtain federal legislation that would render lynching illegal. Throughout these [[lobbying]] efforts, the organization regularly displayed a black flag stating "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday" from the window of its New York offices to mark each outrage. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In October of 1919, the organization sent Walter Francis White to Phillips County, Arkansas to investigate the Elaine Race Riot, a massacre of more than two hundred black Americans by white vigilantes and federal troops after a deputy sheriff's attack on a meeting of sharecroppers left one white man dead. One month later, the NAACP organized the appeals on behalf of twelve black men sentenced to death based on confessional evidence obtained through beatings and electric shocks. The organization obtained a groundbreaking Supreme Court decision in ''Moore v. Dempsey'' that significantly expanded the federal court's jurisdiction over state criminal justice systems. | |

| − | + | The NAACP was successful in working with the American Federation of Labor to prevent the nomination of Judge John Johnston Parker to the Supreme Court, basing their opposition to Parker around his efforts to deny blacks the right to vote. The organization later organized support for the Scottsboro Boys, a controversial trial surrounding nine young black men eventually acquitted of false [[rape]] charges. Although the NAACP lost most of the internecine battles with the U.S. Communist Party and the International Labor Defense regarding the control of cases and strategies to be pursued, the organization was successful in launching litigation challenges against the "white primary" system in the South. | |

| − | + | ==Desegregation== | |

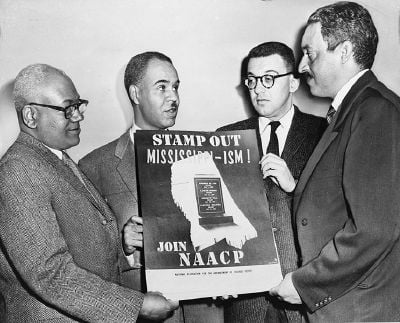

| + | [[File:NAACP leaders with poster NYWTS.jpg|thumb|400px|NAACP leaders Henry L. Moon, Roy Wilkins, Herbert Hill, and Thurgood Marshall in 1956]] | ||

| + | The NAACP's Legal Department, headed by [[Charles Hamilton Houston]] and [[Thurgood Marshall]], undertook a challenging campaign spanning several decades to eventually reverse the "separate but equal doctrine" allocated by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case ''Plessy v. Ferguson.'' Challenging [[racial segregation]] in state professional schools, and later at the [[college]] level, the organization’s campaign culminated in a unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision of ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]]'' that held any state-sponsored segregation of [[elementary school]]s to be unconstitutional. | ||

| − | + | Bolstered by that victory, the NAACP pushed for full desegregation throughout the South. Starting on December 5, 1955, NAACP activists, including local president Edgar Nixon and former chapter secretary [[Rosa Parks]], helped to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. This movement was launched to protest racial segregation on Montgomery buses, a city where two-thirds of all riders were black. The [[boycott]] lasted 381 days. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The state of Alabama responded in 1958 by effectively barring the NAACP from operating within its borders. The organization refused to divulge a list of its members to the state, fearing that they would be fired from their employment or face violent retaliation for their status. While the Supreme Court eventually overturned the state’s decisions in ''NAACP v. Alabama,'' the organization lost much of its influence within the [[American Civil Rights Movement]] to organizations such as the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. These organizations relied more on direct action and mass mobilization, rather than litigation and legislation to advance the rights of black Americans. Roy Wilkins, president of the NAACP at the time, clashed repeatedly with civil rights leaders, including [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]], over questions of strategy and prestige within the movement. | |

| + | [[File:Bomb-damaged home of Arthur Shores (5 September 1963).jpg|thumb|400px|The bomb-damaged home of Arthur Shores, NAACP attorney, Birmingham, Alabama, on September 5, 1963]] | ||

| + | During this time, the NAACP continued to use the Supreme Court's decision in ''Brown v. Board of Education'' to press for the desegregation of all schools and public facilities throughout the country. Civil rights activist [[Daisy Bates]], president of the NAACP Arkansas chapter, spearheaded a campaign to racially integrate the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas. | ||

| − | + | By the mid-1960s, the NAACP had regained some of its prominence in the Civil Rights Movement by lobbying for civil rights legislation. On August 28, 1963, the organization helped to launch The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and later played a pivotal role in the Congressional passing of a [[Civil Rights Act of 1964|civil rights bill]] to end racial discrimination in employment, education, and public accommodations in 1964. The passage of a voting rights act followed in 1965. | |

| − | + | == Crisis and Restored Strength== | |

| + | In the early 1990s, the NAACP ran into [[debt]], and the subsequent dismissal of two leading officials added to the picture of an organization in deep crisis. In 1993, the organization’s Board of Directors selected Reverend Benjamin Chavis by a narrow margin over candidate Reverend Jesse Jackson to fill the position of Executive Secretary. A controversial figure, Chavis was ousted eighteen months later by the same board that hired him, accused of using NAACP funds for an out-of-court settlement in a sexual harassment lawsuit. | ||

| − | + | Following the dismissal of Chavis, Myrlie Evers-Williams narrowly defeated NAACP chairperson William Gibson in 1995 to fill the executive secretary position, after opponent Gibson was accused of mismanaging the organization's funds. In 1996, Kweisi Mfume, a democratic U.S. Congressman from Maryland and former head of the Congressional Black Caucus, was named president of the NAACP. Strained finances just three years later forced the organization to drastically cut its staff from 250 to 50. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | By the end of the 1990s the organization restored its finances, permitting the NAACP National Voter Fund to launch a major "get-out-the-vote" campaign in the 2000 U.S. presidential election. Ten and a half million black Americans cast their ballots, an increase of more than one million from the previous election. The campaign launched by the NAACP was believed to play a significant role in swaying several undecided states, such as Pennsylvania and Michigan, toward Democratic nominee Al Gore. | |

| − | + | ==The NAACP and the Twenty-First Century== | |

| + | The mission of the NAACP stands to ensure [[politics|political]], [[education]]al, social, and economic equality of all persons, and to eliminate [[racism|racial]] hatred and discrimination throughout the United States. Members and affiliates share in the organization’s vision of a society devoid of racial hatred and discrimination, in which all individuals have equal rights. | ||

| − | + | NAACP action of the twenty-first century has included numerous legislative [[lobbying]] campaigns to advocate on behalf of immigration rights, [[affirmative action]], and [[minimum wage]] legislation. Campaigns have also been launched to address the racial and ethnic economic disparity that has continued to exist within the United States. Strategies to address this gap have included public awareness campaigns, the promotion and development of black- and Latino-owned businesses, the elimination of housing discrimination, and significant sponsorship efforts to ensure proportional representation within corporate America. | |

| − | + | A second particular area of interest taken up by the NAACP in the twenty-first century has been to remove legislative disincentives for minority Americans and increase the participation of black Americans in the U.S. democratic process. By promoting awareness and education, and supporting voter-registration efforts, the NAACP has made significant strides in increasing the numbers of black American voter–turnouts each electoral year. The organization has also linked its voter-participation campaign with numerous lobbying efforts to ensure that legislative initiatives support and progress the agenda of American civil rights. | |

| − | + | Through active involvement with the U.S. democratic process to secure and protect national civil rights, the NAACP and its eleven subdivisions and programs continue to take on issues regarding education, economic empowerment, civic engagement, and international affairs to ensure and perpetuate the organization’s continued significance in the twenty-first century. | |

==Timeline== | ==Timeline== | ||

| − | |||

| − | '''1909:''' On | + | '''1909:''' On February 12, the National Negro Committee is formed. Founders include Ida Wells-Barnett, [[W.E.B. Du Bois]], Henry Moskowitz, [[Mary White Ovington]], Oswald Garrison Villiard, and William English Walling. |

| − | '''1910:''' | + | '''1910:''' The NAACP begins court proceedings regarding the Pink Franklin case, a suit involving a black farmhand who killed a policeman in an act of [[self-defense]] when the officer broke into his home to arrest him on a civil charge. |

| − | '''1913:''' The NAACP | + | '''1913:''' The NAACP protests U.S. President [[Woodrow Wilson]]'s official introduction of [[racial segregation]] to the federal government. |

| − | '''1914''' | + | '''1914:''' Professor Emeritus Joel Spingarn of [[Columbia University]] becomes chairman of the NAACP and recruits for its board such Jewish leaders as Jacob Schiff, Jacob Billikopf, and Rabbi Stephen Wise. Spingarn also establishes the Spingarn Medal, awarded annually for outstanding achievement by a black American. |

| − | '''1915:''' The NAACP | + | '''1915:''' The NAACP organizes a nationwide protest against D.W. Griffith's racially inflammatory film, ''Birth of a Nation''. |

| − | '''1917:''' In ''Buchanan v. Warley'', the [[ | + | '''1917:''' In ''Buchanan v. Warley'', the [[U.S. Supreme Court]] rules that states cannot restrict and officially segregate black Americans into residential districts. The NAACP also wins a battle to enable black Americans to be commissioned as officers in [[World War I]]. Six hundred officers are commissioned, and 700,000 black American men are registered for the draft. |

| − | '''1918:''' After pressure by the NAACP, President Woodrow Wilson | + | '''1918:''' After pressure by the NAACP, President Woodrow Wilson makes a public statement against [[lynching]]. |

| − | '''1919:''' The NAACP sends Walter F. White to | + | '''1919:''' The NAACP sends Walter F. White to Arkansas to investigate the mass [[murder]] of two hundred black tenant farmers. The association also organizes the appeals on behalf of more than a hundred African-American defendants convicted in mob-dominated judicial proceedings. |

| − | '''1920:''' | + | '''1920:''' The NAACP's annual conference is held in Atlanta, Georgia, an area considered to be one of the most active areas of [[Ku Klux Klan]] activities. Members chose this location in the face of attempted intimidation on behalf of Klan operations. |

| − | '''1922:''' The NAACP | + | '''1922:''' The NAACP places large ads in major newspapers nationwide to spread awareness and present facts about lynching. |

| − | '''1930:''' The first of successful protests by the NAACP against Supreme Court justice nominees | + | '''1930:''' The first of many successful protests organized by the NAACP against Supreme Court justice nominees begins against Judge John Parker who favored laws that discriminated against black Americans. |

| − | '''1935:''' NAACP lawyers [[Charles Hamilton Houston]] and [[Thurgood Marshall]] | + | '''1935:''' NAACP lawyers [[Charles Hamilton Houston]] and [[Thurgood Marshall]] win a legal battle to admit the first black student, Donald Gaines Murray, to the University of Maryland’s Law School. |

| − | '''1939:''' | + | '''1939:''' The NAACP helps to organize an open-air concert at the Washington, D.C. Lincoln Memorial for the acclaimed contralto Marian Anderson. Anderson, having been barred from performing at Constitution Hall by the [[Daughters of the American Revolution]], performs before an audience of 75,000. |

| − | '''1940:''' | + | '''1940:''' The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is founded. |

| − | '''1941:''' | + | '''1941:''' The NAACP helps to support President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]’s World War II order of a nondiscrimination policy in war-related industries and federal employment. |

| − | + | '''1954:''' Under the leadership of special counsel Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP wins the controversial ''Brown v. Board of Education'', a historic U.S. Supreme Court decision barring school segregation. | |

| − | '''1954:''' | ||

| − | '''1955:''' NAACP member and volunteer [[Rosa Parks]] is arrested and fined for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in | + | '''1955:''' NAACP member and volunteer [[Rosa Parks]] is arrested and fined for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. This action becomes a catalyst for the largest grassroots civil rights movement in the U.S., spearheaded through the collective efforts of the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and smaller black organizations. |

| − | '''1957:''' | + | '''1957:''' The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund becomes a separate organization. |

| − | '''1960:''' In | + | '''1960:''' In Greensboro, North Carolina, members of the NAACP Youth Council start a series of nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters throughout the state. These protests eventually lead to more than sixty stores officially desegregating their counters. |

| − | '''1963:''' After | + | '''1963:''' After a mass rally for civil rights, [[Medgar Evers]], the NAACP's first field director of its Mississippi Chapter, is assassinated in front of his home in Jackson, Mississippi. |

| − | '''1963:''' The NAACP pushed for passage of the | + | '''1963:''' The NAACP pushed for passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission–supported Equal Employment Opportunity Act. |

| − | '''1964:''' The U.S. Supreme Court | + | '''1964:''' The U.S. Supreme Court ends the eight-year effort of Alabama officials to ban NAACP activities within the state. |

| − | '''1965:''' Amidst threats of violence and efforts of state and local governments, the NAACP | + | '''1965:''' Amidst threats of violence and efforts of state and local governments, the NAACP registers more than 80,000 voters in the Southern United States. |

| − | '''1975''' Margaret Bush Wilson, a St. Louis attorney, becomes the | + | '''1975:''' Margaret Bush Wilson, a St. Louis attorney, becomes the first female black American to chair the NAACP’s National Board of Directors. |

| − | first | ||

| − | '''1979:''' The NAACP initiates the first bill ever signed by a governor that allows voter registration in high schools. | + | '''1979:''' The NAACP initiates the first bill ever signed by a governor that allows voter registration in high schools. Twenty-four states follow suit. |

| − | '''1981:''' The NAACP | + | '''1981:''' The NAACP leads the effort to extend the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years. To cultivate economic empowerment, the NAACP establishes the Fair Share Program in conjunction with major corporations across the country. |

| − | '''1982:''' NAACP | + | '''1982:''' The NAACP registers more than 850,000 additional voters. |

| − | '''1989:''' the NAACP | + | '''1989:''' the NAACP holds a silent march of more than 100,000 people to protest various U.S. Supreme Court decisions that reverse many of the previous gains made against racial discrimination. |

| − | + | '''1991:''' The NAACP launches a voter registration campaign to defeat avowed Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke from securing the position of U.S. Senator for the state of Louisiana. The campaign yields a 76-percent turnout rate and defeats Duke’s aspirations. | |

| − | '''1991:''' | ||

| − | '''1995:''' | + | '''1995:''' Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers, is elected to lead the NAACP's board of directors. |

| − | '''1996:''' | + | '''1996:''' Kweisi Mfume, after leaving the United States House of Representatives, becomes the president of the NAACP. |

| − | '''1996:''' Responding to anti-[[affirmative action]] legislation | + | '''1996:''' Responding to national anti-[[affirmative action]] legislation, the NAACP launches the Economic Reciprocity Program. In later response to increased violence among black youth, the organization organizes the "Stop The Violence, Start the Love" campaign. |

| − | '''2000:''' | + | '''2000:''' The NAACP helps to accomplish television diversity agreements and produces the largest voter turnout of black Americans in 20 years. |

| − | '''2002:''' | + | '''2002:''' Protesting the presence of the Confederate Battle Flag on South Carolina’s State House grounds, the NAACP launches separate protests at the Bi-Lo Center and the Carolina Coliseum for hosting the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) men's and women's basketball tournaments. The NCAA follows by banning South Carolina–based venues from hosting any future championship events. The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) quickly prohibits Knights Castle, based in Fort Mill, South Carolina, from hosting its national baseball tournament. |

| − | '''2005:''' Following the resignation of | + | '''2005:''' Following the resignation of Kweisi Mfume, business executive Bruce S. Gordon is chosen unanimously to serve as president of the NAACP. |

| − | '''2005:''' Civil rights pioneer and lifetime NAACP member | + | '''2005:''' Civil rights pioneer and lifetime NAACP member Rosa Parks dies, her body laid in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. She is the first woman ever to be so honored. |

| − | '''2006:''' The NAACP announces plans to move its national headquarters from Baltimore to | + | '''2006:''' The NAACP announces plans to move its national headquarters from Baltimore, Maryland to Washington, D.C. |

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Dalfiume, Richard. 1969. "The Forgotten Years of the Negro Revolution." ''Journal of American History'' 55:99-100. | |

| − | * | + | *Fleming, Cynthia Griggs. 2004. ''In the Shadow of Selma: The Continuing Struggle for Civil Rights in the Rural South.'' Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0742508110 |

| − | * [ | + | *Goings, Kenneth W. 1990. ''The NAACP Comes of Age: The Defeat of Judge John J. Parker.'' Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253325854 |

| − | * | + | *Hughes, Langston. 1962. ''Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP.'' University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826213715 |

| − | * | + | *Janken, Kenneth Robert. 2003. ''White: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP.'' New Press. ISBN 1565847733 |

| − | * | + | *Jonas, Gilbert S. 2004. ''Freedom's Sword: The NAACP and the Struggle against Racism in America, 1909-1969.'' Routledge. ISBN 0415949858 |

| + | *Lewis, David Levering. [1994] 2001. ''W.E.B. DuBois: Biography of a Race.'' Owl Books. Pulitzer Prize. ISBN 0805035680 | ||

| + | *Mosnier, L. Joseph. 2005. ''Crafting Law in the Second Reconstruction: Julius Chambers, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Title VII.'' U. of North Carolina. | ||

| + | *Ross, Barbara Joyce. 1972. ''J. E. Spingarn and the Rise of the NAACP, 1911-1939.'' Scribner. ISBN 0689703376 | ||

| + | *Sachar, Howard. 1992. ''A History of the Jews in America''. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394573533 | ||

| + | *Schneider, Mark Robert. 2001. ''We Return Fighting: The Civil Rights Movement in the Jazz Age.'' Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555534902 | ||

| + | *St. James, Warren D. 1958. ''The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: A Case Study in Pressure Groups.'' | ||

| + | *Topping, Simon. 2004. "'Supporting Our Friends and Defeating Our Enemies': Militancy and Nonpartisanship in the NAACP, 1936-1948." ''The Journal of African American History'' (Jan. 1). | ||

| + | *Zangrando, Robert. 1980. ''The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950.'' Temple University Press. ISBN 087722174X | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved October 31, 2023. | |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://naacp.org/ NAACP Official site] |

| − | *[ | + | * [https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/naacp/founding-and-early-years.html NAACP: A Century in the Fight for Freedom] ''Library of Congress'' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit1|National_Association_for_the_Advancement_of_Colored_People|72723476|}} | {{Credit1|National_Association_for_the_Advancement_of_Colored_People|72723476|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:05, 31 October 2023

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, also known as the NAACP, is one of the oldest and most influential civil rights organizations in the United States. Founded on February 12, 1909, the Association was created to work toward the betterment and advancement of black Americans nationwide. Members often refer to the organization as The National Association, in reference to the association’s pre-eminence among similar organizations active in the struggle for civil rights and equality in the early twentieth century. Its title, retained in accord with tradition, represents one of the last surviving usages of the term "colored people." Although this term generally became viewed as dated and derogatory, in the historical context of the NAACP the term is considered inoffensive.

The history of the NAACP includes significant victories, notably in ending racial segregation in education, in bringing public attention to lynchings of black Americans, and in successful voter registration of black Americans and their subsequent voting in elections. The NAACP, however, has also experienced many internal struggles concerning its methods in achieving equality of rights. Such difficulties were evident in its beginnings when W.E.B. Du Bois clashed with others over the involvement of white leadership, through its loss of influence in the American Civil Rights Movement to other organizations and civil rights leaders, and continued in more recent times with financial difficulties including mismanagement of funds by the leadership. Nevertheless, the NAACP emerged into the twenty-first century complete with a vision of racial equality in American society, and the determination and resources to work towards it. Until such time as racism, both in thought and action, is completely overcome and all people are considered part of the same human family, there is work to be done and the NAACP is ready to do it.

Organization

The NAACP's headquarters are located in Baltimore, Maryland, with additional regional offices located in California, New York, Michigan, Missouri, Georgia, and Texas. Each incorporates local youth and college chapters to organize local community activities for individual members. As of 2004, the NAACP had approximately 500,000 members.

The NAACP is run nationally by a 64-member board of directors led by a chairman. The board is responsible for electing one president and one chief executive officer for the national organization.

The NAACP is divided into various departments and divisions which serve to direct the Association at specific levels. The Association’s Branch and Field Services Department and the Youth and College Department support the operations of local NAACP chapters. The NAACP’s Legal Department focuses on minority court cases, often working to regulate systematic discrimination in environments of employment, government, or education. The Association’s Washington, D.C. Bureau is responsible for the political lobbying of U.S. Government legislation. The organization’s Education Department works for improvements toward public education at the local, state, and federal levels. The goal of the NAACP Health Division is to advance healthcare for minorities through public policy initiatives and education.

History

In 1905, a group of thirty-two prominent, outspoken black American men met to discuss the challenges facing "people of color," a term referring to those who did not have white skin or were not of a Caucasian background. The meeting was designed to create potential strategies and solutions for the societal betterment of all colored people throughout the United States. Under the leadership of Harvard University scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, the meeting took place at Niagara Falls, and as a result the group came to be known as the "Niagara Movement." Due to existing U.S. hotel regulations regarding racial segregation, the meeting took place at a hotel situated across the border in Canada. One year later, three whites joined the movement, social workers Mary White Ovington and Henry Moskowitz, and journalist William E. Walling.

For a time, the fledgling group struggled with limited resources. To increase its scope and effectiveness, the movement decided to broaden its membership and soon sent solicitations for support to more than sixty prominent Americans of the day. A later meeting, intentionally set to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the birth of United States President Abraham Lincoln, was set for February 12, 1909. Though the actual meeting did not occur until three months later, this date is often cited as the founding date of the national organization.

On May 30, 1909, the Niagara Movement’s second conference took place in New York City's Henry Street Settlement House. From this meeting, an organization of more than forty like-minded individuals emerged, and was quickly entitled the National Negro Committee. Once again, Du Bois played a key role in organizing the event and presided over the New York proceedings. Also in attendance was African American journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

One year earlier, the Springfield Race Riot of 1908 in Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois, highlighted an urgent need for a large civil rights organization to be formed within the United States. This event is often represented as the spark that initiated the development and formation of the NAACP.

In May of 1910, the members adopted the name National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The organization was formally incorporated the following year, and delineated its mission as follows:

To promote equality of rights and to eradicate caste or race prejudice among the citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for the children, employment according to their ability and complete equality before law.

The 1911 conference resulted in a more viable, influential, and diverse organization, with a leadership that was predominately white and heavily Jewish. At its founding, the NAACP included just one black American on its executive board, Du Bois, and did not elect a black president until 1975. In its early stages, the Jewish community contributed greatly to the organization’s founding and finances. Jewish co-founders included Lillian Wald, Rabbi Emil G. Hirsch, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and Chairman Joel Elias Spingarn, a Professor Emeritus of Columbia University.

From its foundation in 1909 until 1930, Moorfield Storey served as president of the NAACP. Storey, a Caucasian, was a long-time Democratic liberal who advocated for laissez-faire free markets, supported the gold standard, and opposed imperialism. Storey consistently and aggressively championed civil rights not only for blacks but also for American Indians and immigrant populations, publicly opposing immigration restrictions.

As a member of the executive board, conference leader W.E.B Du Bois played a pivotal role in the early operations of the organization, and served as editor of the association's magazine, The Crisis, a publication with a circulation of more than 30,000.

Fighting Jim Crow

In its early years, the NAACP concentrated on using the courts to overturn the Jim Crow statutes that legalized racial discrimination. In 1913, the association organized opposition to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's introduction of racial segregation into federal government policy.

By 1914, with more than 6,000 members and 50 branches, the organization was influential in winning the right of African-Americans to serve as officers in World War I. Six hundred African-American officers were commissioned and 700,000 African Americans registered for the draft. The following year the NAACP organized a nationwide protest against filmmaker D.W. Griffith's silent film Birth of a Nation, a film that glamorized the Ku Klux Klan.

The NAACP began playing a prominent role in lawsuits targeting racial segregation and other denials of civil liberties. The organization challenged Oklahoma’s discriminatory "grandfather" rule that disenfranchised its state residents, and in 1917 persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court under Buchanan v. Warley to deny states and local governments the right to officially segregate black Americans into separate residential districts.

In 1916, NAACP chairman Joel Spingarn invited James Weldon Johnson to serve as the organization’s field secretary. Through the efforts of Johnson, a former U.S. consul to Venezuela and noted scholar and columnist, NAACP membership jumped from 9,000 to almost 90,000 within four years. In 1920, Johnson was elected head of the organization. Over the next ten years, the NAACP escalated its lobbying and litigation efforts, becoming internationally known for its advocacy of equal rights and equal protection for the "American Negro."

Between the First and Second World Wars, the NAACP devoted much of its effort to prevent the lynching of black Americans throughout the United States. The NAACP worked for more than a decade to obtain federal legislation that would render lynching illegal. Throughout these lobbying efforts, the organization regularly displayed a black flag stating "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday" from the window of its New York offices to mark each outrage.

In October of 1919, the organization sent Walter Francis White to Phillips County, Arkansas to investigate the Elaine Race Riot, a massacre of more than two hundred black Americans by white vigilantes and federal troops after a deputy sheriff's attack on a meeting of sharecroppers left one white man dead. One month later, the NAACP organized the appeals on behalf of twelve black men sentenced to death based on confessional evidence obtained through beatings and electric shocks. The organization obtained a groundbreaking Supreme Court decision in Moore v. Dempsey that significantly expanded the federal court's jurisdiction over state criminal justice systems.

The NAACP was successful in working with the American Federation of Labor to prevent the nomination of Judge John Johnston Parker to the Supreme Court, basing their opposition to Parker around his efforts to deny blacks the right to vote. The organization later organized support for the Scottsboro Boys, a controversial trial surrounding nine young black men eventually acquitted of false rape charges. Although the NAACP lost most of the internecine battles with the U.S. Communist Party and the International Labor Defense regarding the control of cases and strategies to be pursued, the organization was successful in launching litigation challenges against the "white primary" system in the South.

Desegregation

The NAACP's Legal Department, headed by Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, undertook a challenging campaign spanning several decades to eventually reverse the "separate but equal doctrine" allocated by the Supreme Court in the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson. Challenging racial segregation in state professional schools, and later at the college level, the organization’s campaign culminated in a unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education that held any state-sponsored segregation of elementary schools to be unconstitutional.

Bolstered by that victory, the NAACP pushed for full desegregation throughout the South. Starting on December 5, 1955, NAACP activists, including local president Edgar Nixon and former chapter secretary Rosa Parks, helped to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. This movement was launched to protest racial segregation on Montgomery buses, a city where two-thirds of all riders were black. The boycott lasted 381 days.

The state of Alabama responded in 1958 by effectively barring the NAACP from operating within its borders. The organization refused to divulge a list of its members to the state, fearing that they would be fired from their employment or face violent retaliation for their status. While the Supreme Court eventually overturned the state’s decisions in NAACP v. Alabama, the organization lost much of its influence within the American Civil Rights Movement to organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. These organizations relied more on direct action and mass mobilization, rather than litigation and legislation to advance the rights of black Americans. Roy Wilkins, president of the NAACP at the time, clashed repeatedly with civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., over questions of strategy and prestige within the movement.

During this time, the NAACP continued to use the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education to press for the desegregation of all schools and public facilities throughout the country. Civil rights activist Daisy Bates, president of the NAACP Arkansas chapter, spearheaded a campaign to racially integrate the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas.

By the mid-1960s, the NAACP had regained some of its prominence in the Civil Rights Movement by lobbying for civil rights legislation. On August 28, 1963, the organization helped to launch The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and later played a pivotal role in the Congressional passing of a civil rights bill to end racial discrimination in employment, education, and public accommodations in 1964. The passage of a voting rights act followed in 1965.

Crisis and Restored Strength

In the early 1990s, the NAACP ran into debt, and the subsequent dismissal of two leading officials added to the picture of an organization in deep crisis. In 1993, the organization’s Board of Directors selected Reverend Benjamin Chavis by a narrow margin over candidate Reverend Jesse Jackson to fill the position of Executive Secretary. A controversial figure, Chavis was ousted eighteen months later by the same board that hired him, accused of using NAACP funds for an out-of-court settlement in a sexual harassment lawsuit.

Following the dismissal of Chavis, Myrlie Evers-Williams narrowly defeated NAACP chairperson William Gibson in 1995 to fill the executive secretary position, after opponent Gibson was accused of mismanaging the organization's funds. In 1996, Kweisi Mfume, a democratic U.S. Congressman from Maryland and former head of the Congressional Black Caucus, was named president of the NAACP. Strained finances just three years later forced the organization to drastically cut its staff from 250 to 50.

By the end of the 1990s the organization restored its finances, permitting the NAACP National Voter Fund to launch a major "get-out-the-vote" campaign in the 2000 U.S. presidential election. Ten and a half million black Americans cast their ballots, an increase of more than one million from the previous election. The campaign launched by the NAACP was believed to play a significant role in swaying several undecided states, such as Pennsylvania and Michigan, toward Democratic nominee Al Gore.

The NAACP and the Twenty-First Century

The mission of the NAACP stands to ensure political, educational, social, and economic equality of all persons, and to eliminate racial hatred and discrimination throughout the United States. Members and affiliates share in the organization’s vision of a society devoid of racial hatred and discrimination, in which all individuals have equal rights.

NAACP action of the twenty-first century has included numerous legislative lobbying campaigns to advocate on behalf of immigration rights, affirmative action, and minimum wage legislation. Campaigns have also been launched to address the racial and ethnic economic disparity that has continued to exist within the United States. Strategies to address this gap have included public awareness campaigns, the promotion and development of black- and Latino-owned businesses, the elimination of housing discrimination, and significant sponsorship efforts to ensure proportional representation within corporate America.

A second particular area of interest taken up by the NAACP in the twenty-first century has been to remove legislative disincentives for minority Americans and increase the participation of black Americans in the U.S. democratic process. By promoting awareness and education, and supporting voter-registration efforts, the NAACP has made significant strides in increasing the numbers of black American voter–turnouts each electoral year. The organization has also linked its voter-participation campaign with numerous lobbying efforts to ensure that legislative initiatives support and progress the agenda of American civil rights.

Through active involvement with the U.S. democratic process to secure and protect national civil rights, the NAACP and its eleven subdivisions and programs continue to take on issues regarding education, economic empowerment, civic engagement, and international affairs to ensure and perpetuate the organization’s continued significance in the twenty-first century.

Timeline

1909: On February 12, the National Negro Committee is formed. Founders include Ida Wells-Barnett, W.E.B. Du Bois, Henry Moskowitz, Mary White Ovington, Oswald Garrison Villiard, and William English Walling.

1910: The NAACP begins court proceedings regarding the Pink Franklin case, a suit involving a black farmhand who killed a policeman in an act of self-defense when the officer broke into his home to arrest him on a civil charge.

1913: The NAACP protests U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's official introduction of racial segregation to the federal government.

1914: Professor Emeritus Joel Spingarn of Columbia University becomes chairman of the NAACP and recruits for its board such Jewish leaders as Jacob Schiff, Jacob Billikopf, and Rabbi Stephen Wise. Spingarn also establishes the Spingarn Medal, awarded annually for outstanding achievement by a black American.

1915: The NAACP organizes a nationwide protest against D.W. Griffith's racially inflammatory film, Birth of a Nation.

1917: In Buchanan v. Warley, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that states cannot restrict and officially segregate black Americans into residential districts. The NAACP also wins a battle to enable black Americans to be commissioned as officers in World War I. Six hundred officers are commissioned, and 700,000 black American men are registered for the draft.

1918: After pressure by the NAACP, President Woodrow Wilson makes a public statement against lynching.

1919: The NAACP sends Walter F. White to Arkansas to investigate the mass murder of two hundred black tenant farmers. The association also organizes the appeals on behalf of more than a hundred African-American defendants convicted in mob-dominated judicial proceedings.

1920: The NAACP's annual conference is held in Atlanta, Georgia, an area considered to be one of the most active areas of Ku Klux Klan activities. Members chose this location in the face of attempted intimidation on behalf of Klan operations.

1922: The NAACP places large ads in major newspapers nationwide to spread awareness and present facts about lynching.

1930: The first of many successful protests organized by the NAACP against Supreme Court justice nominees begins against Judge John Parker who favored laws that discriminated against black Americans.

1935: NAACP lawyers Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall win a legal battle to admit the first black student, Donald Gaines Murray, to the University of Maryland’s Law School.

1939: The NAACP helps to organize an open-air concert at the Washington, D.C. Lincoln Memorial for the acclaimed contralto Marian Anderson. Anderson, having been barred from performing at Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution, performs before an audience of 75,000.

1940: The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is founded.

1941: The NAACP helps to support President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s World War II order of a nondiscrimination policy in war-related industries and federal employment.

1954: Under the leadership of special counsel Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP wins the controversial Brown v. Board of Education, a historic U.S. Supreme Court decision barring school segregation.

1955: NAACP member and volunteer Rosa Parks is arrested and fined for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. This action becomes a catalyst for the largest grassroots civil rights movement in the U.S., spearheaded through the collective efforts of the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and smaller black organizations.

1957: The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund becomes a separate organization.

1960: In Greensboro, North Carolina, members of the NAACP Youth Council start a series of nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters throughout the state. These protests eventually lead to more than sixty stores officially desegregating their counters.

1963: After a mass rally for civil rights, Medgar Evers, the NAACP's first field director of its Mississippi Chapter, is assassinated in front of his home in Jackson, Mississippi.

1963: The NAACP pushed for passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission–supported Equal Employment Opportunity Act.

1964: The U.S. Supreme Court ends the eight-year effort of Alabama officials to ban NAACP activities within the state.

1965: Amidst threats of violence and efforts of state and local governments, the NAACP registers more than 80,000 voters in the Southern United States.

1975: Margaret Bush Wilson, a St. Louis attorney, becomes the first female black American to chair the NAACP’s National Board of Directors.

1979: The NAACP initiates the first bill ever signed by a governor that allows voter registration in high schools. Twenty-four states follow suit.

1981: The NAACP leads the effort to extend the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years. To cultivate economic empowerment, the NAACP establishes the Fair Share Program in conjunction with major corporations across the country.

1982: The NAACP registers more than 850,000 additional voters.

1989: the NAACP holds a silent march of more than 100,000 people to protest various U.S. Supreme Court decisions that reverse many of the previous gains made against racial discrimination.

1991: The NAACP launches a voter registration campaign to defeat avowed Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke from securing the position of U.S. Senator for the state of Louisiana. The campaign yields a 76-percent turnout rate and defeats Duke’s aspirations.

1995: Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers, is elected to lead the NAACP's board of directors.

1996: Kweisi Mfume, after leaving the United States House of Representatives, becomes the president of the NAACP.

1996: Responding to national anti-affirmative action legislation, the NAACP launches the Economic Reciprocity Program. In later response to increased violence among black youth, the organization organizes the "Stop The Violence, Start the Love" campaign.

2000: The NAACP helps to accomplish television diversity agreements and produces the largest voter turnout of black Americans in 20 years.

2002: Protesting the presence of the Confederate Battle Flag on South Carolina’s State House grounds, the NAACP launches separate protests at the Bi-Lo Center and the Carolina Coliseum for hosting the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) men's and women's basketball tournaments. The NCAA follows by banning South Carolina–based venues from hosting any future championship events. The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) quickly prohibits Knights Castle, based in Fort Mill, South Carolina, from hosting its national baseball tournament.

2005: Following the resignation of Kweisi Mfume, business executive Bruce S. Gordon is chosen unanimously to serve as president of the NAACP.

2005: Civil rights pioneer and lifetime NAACP member Rosa Parks dies, her body laid in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. She is the first woman ever to be so honored.

2006: The NAACP announces plans to move its national headquarters from Baltimore, Maryland to Washington, D.C.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dalfiume, Richard. 1969. "The Forgotten Years of the Negro Revolution." Journal of American History 55:99-100.

- Fleming, Cynthia Griggs. 2004. In the Shadow of Selma: The Continuing Struggle for Civil Rights in the Rural South. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 0742508110

- Goings, Kenneth W. 1990. The NAACP Comes of Age: The Defeat of Judge John J. Parker. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253325854

- Hughes, Langston. 1962. Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826213715

- Janken, Kenneth Robert. 2003. White: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP. New Press. ISBN 1565847733

- Jonas, Gilbert S. 2004. Freedom's Sword: The NAACP and the Struggle against Racism in America, 1909-1969. Routledge. ISBN 0415949858

- Lewis, David Levering. [1994] 2001. W.E.B. DuBois: Biography of a Race. Owl Books. Pulitzer Prize. ISBN 0805035680

- Mosnier, L. Joseph. 2005. Crafting Law in the Second Reconstruction: Julius Chambers, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Title VII. U. of North Carolina.

- Ross, Barbara Joyce. 1972. J. E. Spingarn and the Rise of the NAACP, 1911-1939. Scribner. ISBN 0689703376

- Sachar, Howard. 1992. A History of the Jews in America. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394573533

- Schneider, Mark Robert. 2001. We Return Fighting: The Civil Rights Movement in the Jazz Age. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1555534902

- St. James, Warren D. 1958. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People: A Case Study in Pressure Groups.

- Topping, Simon. 2004. "'Supporting Our Friends and Defeating Our Enemies': Militancy and Nonpartisanship in the NAACP, 1936-1948." The Journal of African American History (Jan. 1).

- Zangrando, Robert. 1980. The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950. Temple University Press. ISBN 087722174X

External links

All links retrieved October 31, 2023.

- NAACP Official site

- NAACP: A Century in the Fight for Freedom Library of Congress

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.