Miracle

A miracle (from Latin: miraculum meaning "something wonderful") is an extraordinary and amazing event that defies social expectation, and is often attributed to divine intervention in the universe by which the ordinary course and operation of Nature is overruled, suspended, or modified. Although many religious texts and people confirm witnessing "miracles", it is disputed whether such events are scientifically confirmed occurrences. Sometimes the term "miracle" may refer to the action of a supernatural being that is not a god. Thus, the term "divine intervention", by contrast, would refer specifically to the direct involvement of a deity, demons Simon Magus.

In casual usage, "miracle" may also refer to any statistically unlikely but beneficial event, (such as the survival of a natural disaster) or even to anything which is regarded as "wonderful" regardless of its likelihood, such as birth.

Levitation

Definition

According to the philosopher David Hume, a miracle is "a transgression of a law of nature by a particular volition of the Deity, or by the interposition of some invisible agent." [1] Some religious believers hold that there is a scientific basis for believing in supernatural miracles. They hold that in the absence of a plausible, parsimonious scientific theory, the best explanation for these events is that they were performed by a supernatural being, e.g. God. In this view, a miracle is a violation of normal laws of nature by a god or some other supernatural being. Some scientist-theologians like Polkinghorne suggest that miracles are not violations of the laws of nature but "exploration of a new regime of physical experience".[2]

The logic behind an event being deemed a miracle varies significantly. In most cases a religious text, such as the Bible or Quran, states that a miracle occurred, and believers accept this as a fact.Therefore, there is probably a supernatural being (i.e., God) that performs what appear to be miracles. However, some scientists criticise this kind of thinking a subversion, or perhaps deliberate misuse, of Ockham's Razor.[3]

Many adherents of monotheistic religions assert that miracles, if established, are logical proof of the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent god. A number of criticisms of this point of view exist:

- While the existence of miracles may imply the existence of a supernatural miracle worker, that supernatural miracle worker need not be an omnipotent, omniscient, and all-benevolent god; it could be any supernatural being. That is, it only proves that gods might exist, not that there is a monotheistic god.

- Some argue that miracles, if established, are evidence that a perfect god does not exist, as such a being would not want to, or need to, violate his own laws of nature.[citation needed]

- Catholic theologians do not accept this reasoning; they conclude that the miracles are from an omnipotent god, because they accept as already logically proven (through concepts like the prime mover) that there must be a single omnipotent, omniscient god, when speaking philosophically.

- Laws of nature are inferred from empirical evidence. Thus if an accepted law of nature ever appeared to have been violated, it could simply be that the accepted law was an erroneous inference from an insufficient set of empirical observations, rather than a supernatural disruption of the true course of nature.

Miracles in the Bible

In the Hebrew Bible

The descriptions of most miracles in the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) are often the same as the common definition of the word: God intervenes in the laws of nature.

A literal reading of the Tanakh shows a number of ways miracles are said to occur: God may suspend or speed up the laws of nature to produce a supernatural occurrence; God can create matter out of nothing; God can breathe life into inanimate matter. The Tanakh does not explain details of how these miracles happen.

The Tanakh attributes many natural occurrences to God, such as the sun rising and setting, and rain falling.

Today many Orthodox Jews, most Christians, and most Muslims adhere to this view of miracles. This view is generally rejected by non-Orthodox Jews, liberal Christians and Unitarian-Universalists.

Many events commonly understood to be miraculous may not actually be instances of the impossible, as commonly believed. For instance, consider the parting of the Sea of Reeds (in Hebrew Yâm-Sûph; often mistranslated as the "Red Sea"). This incident occurred when Moses and Israelites fled from bondage in Egypt, to begin their exodus to the promised land. The book of Exodus does not state that the Reed Sea split in a dramatic fashion. Rather, according to the text God caused a strong wind to slowly drive the shallow waters to land, overnight. There is no claim that God pushed apart the sea as shown in many films; rather, the miracle would be that Israel crossed this precise place, at exactly the right time, when Moses lifted his staff, and that the pursuing Egyptian army then drowned when the wind stopped and the piled waters rushed back in.

Most events later described as miracles are not labeled as such by the Bible; rather the text simply describes what happened. Often these narratives will attribute the cause of these events to God.

In the New Testament

The descriptions of most miracles in the Christian New Testament are often the same as the commonplace definition of the word: God intervenes in the laws of nature. In St John's Gospel the "miracles" are referred to as "signs" and the emphasis is on God demonstrating his underlying normal activity in remarkable ways.[4]

Jesus can turn water into wine; Jesus can create matter out of nothing, and thus turn a loaf of bread into many loaves of bread, Jesus can revive the lives of people considered to be dead. Jesus can rise from the dead. The New Testament does not explain details of how these miracles happen.

Miracles as events pre-planned by God

In rabbinic Judaism, many rabbis mentioned in the Talmud held that the laws of nature were inviolable. The idea of miracles that contravened the laws of nature were hard to accept; however, at the same time they affirmed the truth of the accounts in the Tanakh. Therefore some explained that miracles were in fact natural events that had been set up by God at the beginning of time.

In this view, when the walls of Jericho fell, it was not because God directly brought them down. Rather, God planned that there would be an earthquake at that place and time, so that the city would fall to the Israelites. Instances where rabbinic writings say that God made miracles a part of creation include Midrash Genesis Rabbah 5:45; Midrash Exodus Rabbah 21:6; and Ethics of the Fathers/Pirkei Avot 5:6.

Non-literal interpretations of the text

These views are held by both classical and modern thinkers.

In Numbers 22 is the story of Balaam and the talking donkey. Many hold that for miracles such as this, one must either assert the literal truth of this biblical story, or one must then reject the story as false. However, some Jewish commentators (e.g. Saadiah Gaon and Maimonides) hold that stories such as these were never meant to be taken literally in the first place. Rather, these stories should be understood as accounts of a prophetic experience, which are dreams or visions. (Of course, such dreams and visions could themselves be considered miracles.)

Joseph H. Hertz, a 20th century Jewish biblical commentator, writes that these verses "depict the continuance on the subconscious plane of the mental and moral conflict in Balaam's soul; and the dream apparition and the speaking donkey is but a further warning to Balaam against being misled through avarice to violate God command."

Miracles in Islam

Muslims consider the the Holy Qur'an itself to be a miracle.[5] There are many miracles claimed in connection with Qur'an, either recorded in the Qur'an itself or believed by some Muslims about the book. The Qur'an claims that it has been created in miraculous way as a revelation from Allah (God), as a perfect copy of what was written in heaven and existed there from all eternity.[6] Therefore the verses of the book are referred to as ayat, which also means "a miracle" in the Arabic language.[7]

The Quran claims that Muhammad was illiterate and neither read a book nor wrote a book ([Quran 7:157], [Quran 29:48]) and that he did not know about past events nor could he have possibly known the scientific facts that are mentioned in the Quran.([Quran 3:44], [Quran 11:49], [Quran 28:44]).[8] This is used as an argument in favor of the divine origin of the book. On the other side, some scholars have stated that the claim about Muhammad's illiteracy is based on weak traditions and that it is not convincing. [9][10]

The Qur'an records many miraculous events which happened or are about to happen, most notably the divine judgement of souls of dead people and their heavenly rewards or suffering in hell.[11] Muhammad, as believed by critics, was influenced by older Jewish and Christian traditions, and therefore included many of the wonders known from the Bible into the Quran.[12]

Ahmad Dallal, Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies at Georgetown University, writes that many modern Muslims believe that the Qur'an does make scientific statements, however many classical Muslim commentators and scientists, notably al-Biruni, assigned to the Qur'an a separate and autonomous realm of its own and held that the Qur'an "does not interfere in the business of science nor does it infringe on the realm of science."[13] These medieval scholars argued for the possibility of multiple scientific explanation of the natural phenomena, and refused to subordinate the Qur'an to an ever-changing science.[13] The alleged miracles in the Qur’an are usually classified into areas such as scientific or literary.

Contemporary claims of miracles and evidence

The Roman Catholic Church is hesitant extending validity to a putative miracle. The Church requires a certain number of miracles to occur before granting sainthood to a putative saint, with particularly stringent requirements in validating the miracle's authenticity. [1] The process is overseen by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints [2].

Followers of the Indian gurus Sathya Sai Baba and Swami Premananda claim that they routinely perform miracles. The dominant view among sceptics is that these are predominantly sleight of hand or elaborate magic tricks.

Some modern religious groups claim ongoing occurrence of miraculous events. While some miracles have been proven to be fraudulent (Peter Popoff for an example) others (as the Paschal Fire in Jerusalem) have not proven susceptible to analysis. Some groups are far more cautious about proclaiming apparent miracles genuine than others, although official sanction, or the lack thereof, rarely has much effect on popular belief.

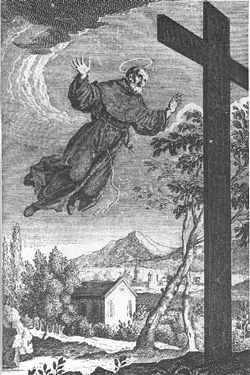

Flying Saints

There are numerous saints to whom the ability to fly or levitate in spite of their weight has been attributed. Most of these flying saints are mentioned as such in literature and sources associated with them.

The ability was also attributed to other figures in early Christianity. The apocryphal Acts of Peter gives a legendary tale of Simon Magus' death. Simon is performing magic in the forum, and in order to prove himself to be a god, he flies up into the air. The apostle Peter prays to God to stop his flying, and he stops mid-air and falls, breaking his legs, whereupon the crowd, previously non-hostile, stones him to death.[14]

The church of Santa Francesca Romana claims to have been built on the spot in question (thus claiming that Simon Magus could indeed fly), claims that Saint Paul was also present, and that a dented slab of marble that it contains bears the imprints of the knees of Peter and Paul during their prayer.

The phenomenon of levitation was recorded again and again for certain saints. Saint Francis of Assisi is recorded as having been "suspended above the earth, often to a height of three, and often to a height of four cubits." St. Alphonsus Liguori, when preaching at Foggia, was lifted before the eyes of the whole congregation several feet from the ground.[15] Liguori is also said to have had the power of bilocation.

Flying or levitation was also associated with witchcraft. When it came to female saints, there was a certain ambivalence expressed by theologians, canon lawyers, inquisitors, and male hagiographers towards the powers that they were purported to have.[16] As Caroline Walker Bynum writes, "by 1500, indeed, the model of the female saint, expressed both in popular veneration and in official canonizations, was in may ways the mirror image of society’s notion of the witch."[17] Both witches and female saints were suspected of flying through the air, whether in saintly levitation or bilocation, or in a witches’ Sabbath.[18]

Skepticism

Many people believe that miracles do not happen and that the entire universe operates on unchangable laws, without any exceptions. Aristotle rejected the idea that God could or would intervene in the order of the natural world. Jewish neo-Aristotelian philosophers, who are still influential today, include Maimonides, Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon, and Gersonides. Directly or indirectly, their views are still prevalent in much of the religious Jewish community.

Littlewood's Law states that individuals can expect a miracle to happen to them at the rate of about one per month.

The law was framed by Cambridge University Professor J. E. Littlewood, and published in a collection of his work, A Mathematician's Miscellany; it seeks (among other things) to debunk one element of supposed supernatural phenomenology and is related to the more general Law of Truly Large Numbers, which states that with a sample size large enough, any outrageous thing is likely to happen.

Littlewood's law, making certain suppositions, is explained as follows: a miracle is defined as an exceptional event of special significance occurring at a frequency of one in a million; during the hours in which a human is awake and alert, a human will experience one thing per second (for instance, seeing the computer screen, the keyboard, the mouse, the article, etc.); additionally, a human is alert for about eight hours per day; and as a result, a human will, in 35 days, have experienced, under these suppositions, 1,008,000 things. Accepting this definition of a miracle, one can be expected to observe one miraculous occurrence within the passing of every 35 consecutive days — and therefore, according to this reasoning, seemingly miraculous events are actually commonplace.

Thus, Littlewood's law states that individuals can expect miracles to happen to them, at the rate of about one per month. By its definition, seemingly miraculous events are actually commonplace. In other words, miracles do not exist, but are rather examples of low probability events that are bound to happen by chance from time to time.

Others have suggested that miracles are the products of creative art and social acceptance. In this view, miracles do not really occur. Rather, they are the product of creative story tellers. They use them to embellish a hero or incident with a theological flavor. Using miracles in a story allow characters and situations to become bigger than life, and to stir the emotions of the listener more than the mundane and ordinary.

Notes

- ↑ Miracles on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ John Polkinghorne Faith, Science and Understanding p59

- ↑ The God Delusion

- ↑ see eg Polkinghorne op cit and any pretty well any commentary on the Gospel of John, such as William Temple Readings in St John's Gospel (see eg p 33) or Tom Wright's John for Everyone

- ↑ F. Tuncer, "International Conferences on Islam in the Contemporary World", March 4-5, 2006, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, U.S.A., p. 95-96

- ↑ Wilson, Christy: "The Qur'an" in A Lion Handbook The World's Religion, p. 315

- ↑ Wilson, ibid.

- ↑ F. Tuncer, ibid

- ↑ William Montgomery Watt, "Muhammad's Mecca", Chapter 3: "Religion In Pre-Islamic Arabia", p. 26-52

- ↑ Maxime Rodinson, "Mohammed", translated by Anne Carter, p. 38-49, 1971

- ↑ Wilson, ibid.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 316

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ahmad Dallal, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Quran and science

- ↑ http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/actspeter.html

- ↑ Montague Summers, Withcraft and Black Magic, (Courier Dover, 2000), 200.

- ↑ Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 23.

- ↑ Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 23.

- ↑ Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 23.

Bibliography

- Charpak, Georges and Henri Broch, translated from the French by Bart K. Holland, Debunked! ESP, Telekinesis, Other Pseudoscience, Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7867-5

- Colin Brown. Miracles and the Critical Mind. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1984. (Good survey).

- Colin J. Humphreys, Miracles of Exodus. Harper, San Francisco, 2003.

- Krista Bontrager, It’s a Miracle! Or, is it?

- Eisen, Robert (1995). Gersonides on Providence, Covenant, and the Chosen People. State University of New York Press.

- Goodman, Lenn E. (1985). Rambam: Readings in the Philosophy of Moses Maimonides. Gee Bee Tee.

- Houdini, Harry. Miracle Mongers and Their Methods: A Complete Expose Prometheus Books; Reprint edition (March 1993) originally published in 1920 ISBN 0-87975-817-1

- Kellner, Menachem (1986). Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought. Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, C.S. Miracles: A Preliminary Study. New York, Macmillan Co., 1947.

- C. F. D. Moule (ed.). Miracles: Cambridge Studies in their Philosophy and History. London, A.R. Mowbray 1966, 1965 (Good survey of Biblical miracles as well).

- Graham Twelftree. Jesus the Miracle Worker: A Historical and Theological Study. IVP, 1999. (Best in its field).

- Woodward, Kenneth L. (2000). The Book of Miracles. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82393-4.

- M. Kamp, MD. Bruno Gröning. The miracles continue to happen. 1998, (Chapters 1 - 4)

- Littlewood's Miscellany, edited by B. Bollobás, Cambridge University Press; 1986. ISBN 0-521-33702-X

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- (1993) A Lion Handbook The World's Religion. Lion Publishing plc. ISBN 0-85648-187-4.

- Ibrahim, I.A (1997). A Brief Illustrated Guide to Understanding Islam. Darussalam. ISBN 9960-34-011-2.

External links

- Human anomalies

- God's Miracles, Islamic perspective

- An Indian Skeptic's explanation of miracles: By Yuktibaadi compiled by Basava Premanand

- Religious miracles

- The Quran Miracles Encyclopedia

- Medical Miracles of the Quran

- Skeptic's Dictionary on miracles

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Why Don't Miracles Happen Today? - A Jewish view on miracles nowadays chabad.org

- On the Cessation of the Charismata — the problem of miracles today.

- Andrew Lang, "Science and 'Miracles'", The Making of Religion Chapter II, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, New York and Bombay, 1900, pp 14-38.

- Littlewood's Law described in a review of Debunked! ESP, Telekinesis, Other Pseudoscience by Freeman J. Dyson, in the New York Review of Books. Full article requires purchase.

- Koran and Nature's Testimony

- The Quran Miracles Encyclopedia

- Exploring The Scientific Miracle of The Qur'an

- Medical Miracles of the Quran

- Quran: The Living Miracle

- Harunyahya.com

- Thewaytotruth.org

- Answering-Islam.org: critique of muslim claims of miracles

- Answering-Christianity.com: Counter-criticism of Answering-Islam's arguements

- Quran-miracle.info

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.