Kafka, Franz

m ({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Ebapproved}}{{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}} {{submitted}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Kafka, Franz}} |

| + | |||

{{Infobox Writer | {{Infobox Writer | ||

| name = Franz Kafka | | name = Franz Kafka | ||

| − | | image = | + | | image = Franz Kafka 1917.jpg |

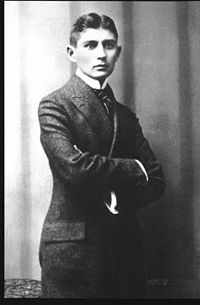

| caption = Photograph of Franz Kafka taken in 1917 | | caption = Photograph of Franz Kafka taken in 1917 | ||

| − | | birth_date = | + | | birth_date = July 3, 1883 |

| birth_place = [[Prague]], [[Austria-Hungary]] (today in the [[Czech Republic]]) | | birth_place = [[Prague]], [[Austria-Hungary]] (today in the [[Czech Republic]]) | ||

| − | | death_date = | + | | death_date = June 3, 1924 |

| death_place = [[Vienna]], [[Austria]] | | death_place = [[Vienna]], [[Austria]] | ||

| occupation = insurance officer, factory manager, novelist, short story writer | | occupation = insurance officer, factory manager, novelist, short story writer | ||

| − | | nationality = [[ | + | | nationality = [[Ashkenazi]] [[Jew]]ish-[[Bohemia|Bohemian]] ([[Austria-Hungary]]) |

| genre = [[novel]], [[short story]] | | genre = [[novel]], [[short story]] | ||

| movement = [[modernism]], [[existentialism]], [[Surrealism]], precursor to [[magical realism]] | | movement = [[modernism]], [[existentialism]], [[Surrealism]], precursor to [[magical realism]] | ||

| magnum opus = [[The Trial]], [[The Castle]], [[The Metamorphosis]] | | magnum opus = [[The Trial]], [[The Castle]], [[The Metamorphosis]] | ||

| influences = [[Søren Kierkegaard]], [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], [[Charles Dickens]], [[Nietzsche]] | | influences = [[Søren Kierkegaard]], [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], [[Charles Dickens]], [[Nietzsche]] | ||

| − | | influenced = [[Albert Camus]], | + | | influenced = [[Albert Camus]], [[Federico Fellini]], [[Gabriel Garcia Marquez]], [[Carlos Fuentes]], [[Salman Rushdie]], [[Haruki Murakami]] |

}} | }} | ||

| − | + | '''Franz Kafka''' (July 3, 1883 – June 3, 1924) was one of the major [[German language]] [[novel|novelists]] and [[short story]] writers of the twentieth century, whose unique body of writing—much of it incomplete and published posthumously despite his wish that it be destroyed—has become iconic in Western literature. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | '''Franz Kafka''' | ||

| − | His most famous pieces of writing include his short story ''Die Verwandlung'' | + | His most famous pieces of writing include his short story ''Die Verwandlung'' ''(The Metamorphosis)'' and his two novels, ''Der Prozess'' ''(The Trial)'' and the unfinished novel ''Das Schloß '' ''(The Castle)''. Kafka's work expresses the essential absurdity of modern society, especially the impersonal nature of [[bureaucracy]] and [[capitalism]]. The individual in Kafka's texts is alone and at odds with the society around him, which seems to operate in a secretive manner that the individual cannot understand. Kafka's world is one in which [[God]] is dead and the individual is "on trial," as the name of his most famous novel suggests. It is a world devoid of meaning or purpose other than to clear one's name of the nebulous sense of guilt that pervades the atmosphere. The adjective "Kafkaesque" has come into common use to denote mundane yet absurd and surreal circumstances of the kind commonly found in Kafka's work. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Kafka's work represents an extreme example of the modern concern with the individual's place in society. As [[modernity]] displaced people from traditional society's fixed meanings and family networks, Kafka exposes the emptiness and even perniciousness of a world in which meaning is not only absent, but malevolent toward the individual. Lacking a transcendent source of value, society is not a hospitable place and meaning is menacing. | ||

== Life == | == Life == | ||

===Family=== | ===Family=== | ||

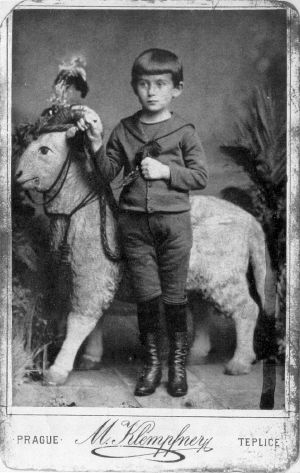

| − | Kafka was born into a middle-class, German-speaking [[Jew]]ish family in [[Prague]], | + | [[Image:Kafka5jahre.jpg|thumb|Kafka at age 5]] |

| + | Kafka was born into a middle-class, German-speaking [[Jew]]ish family in [[Prague]], then capital of [[Bohemia]], a kingdom that was then part of the dual [[monarchy]] of [[Austria-Hungary]]. His father, Hermann Kafka (1852–1931), was described as a "huge, selfish, overbearing businessman"<ref>Stanley Corngold, ''Introduction to The Metamorphosis'' (New York: Bantam Classics, reissue edition, 1972, ISBN 0553213695).</ref> and by Kafka himself as "a true Kafka in strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction, worldly dominance, endurance, presence of mind, [and] knowledge of human nature..."<ref>Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins (trans.), [http://www.kafka-franz.com/KAFKA-letter.htm “Franz Kafka's Letter to his father.”] Available online from Franz Kafka Web Site by Daniel Hornek. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kafka struggled to come to terms with his domineering father. Hermann was the fourth child of Jacob Kafka, a butcher, and came to Prague from Osek, a Jewish village near Písek in southern Bohemia. After working as a traveling sales representative, he established himself as an independent retailer of men's and women's fancy goods and accessories, employing up to 15 people and using a jackdaw (''kavka'' in Czech) as his business logo. Kafka's mother, Julie (1856—1934), was the daughter of Jakob Löwy, a prosperous brewer in Poděbrady, and was better educated than her husband.<ref>Sander L. Gilman, ''Franz Kafka'' (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005, ISBN 1861892543), 20-21.</ref> | ||

| − | Kafka had two younger brothers, Georg and Heinrich, who died at the ages of | + | Kafka had two younger brothers, Georg and Heinrich, who died at the ages of 15 months and six months, respectively, and three younger sisters, Gabriele ("Elli") (1889–1941), Valerie ("Valli") (1890–1942), and Ottilie ("Ottla") (1892–1943). On business days, both parents were absent from the home. His mother helped to manage her husband's business and worked in it as much as 12 hours a day. The children were largely reared by a succession of governesses and servants. |

| − | Kafka's sisters were sent with their families to the Łódź ghetto and died there or in concentration | + | During [[World War II]], Kafka's sisters were sent with their families to the Łódź [[ghetto]] and died there or in [[concentration camp]]s. Ottla is believed to have been sent to the concentration camp at [[Theresienstadt]] and then to the death camp at [[Auschwitz]]. |

===Education=== | ===Education=== | ||

| − | Kafka learned German as his first language, but he was also almost fluent in Czech. Later, Kafka also acquired some knowledge of [[French language]] and culture; one of his favorite authors was [[Gustave Flaubert]]. From 1889 to 1893, he attended the ''Deutsche Knabenschule'', the boys' elementary school at the ''Fleischmarkt'' (meat market), the street now known as Masná Street in Prague. His [[Judaism|Jewish]] education was limited to his ''[[B'nai Mitzvah|Bar Mitzvah]]'' celebration at 13 and going to the [[synagogue]] four times a year with his father. <ref>[http://www.kafka-franz.com/kafka-Biography.htm Franz Kafka Biography] | + | Kafka learned [[German language|German]] as his first [[language]], but he was also almost fluent in [[Czech language|Czech]]. Later, Kafka also acquired some knowledge of the [[French language]] and culture; one of his favorite authors was [[Gustave Flaubert]]. From 1889 to 1893, he attended the ''Deutsche Knabenschule'', the boys' [[elementary school]] at the ''Fleischmarkt'' (meat market), the street now known as Masná Street in [[Prague]]. His [[Judaism|Jewish]] education was limited to his ''[[B'nai Mitzvah|Bar Mitzvah]]'' celebration at 13 and going to the [[synagogue]] four times a year with his father.<ref>Daniel Hornek, [http://www.kafka-franz.com/kafka-Biography.htm Franz Kafka Biography,] Franz Kafka Web Site. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> After elementary school, he was admitted to the rigorous classics-oriented state ''gymnasium'', ''Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium'', an academic [[secondary school]] with eighth grade levels, where German was also the language of instruction, at ''Staroměstské náměstí'', within the Kinsky Palace in the Old Town. He completed his ''Matura'' exams in 1901. |

| − | [[Image:Kafka1906.jpg|thumb| | + | |

| − | Admitted to the Charles University of Prague, Kafka first studied chemistry, but switched after two weeks to law. This offered a range of career possibilities, which pleased his father, and required a longer course of study that gave Kafka time to take classes in German studies and art history. At the university, he joined a student club, named ''Lese- und Redehalle der Deutschen Studenten'', which organized literary events, readings and other activities. In the end of his first year of studies, he met [[Max Brod]], who would become a close friend | + | [[Image:Kafka1906.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Kafka in 1906]] |

| + | Admitted to the Charles University of Prague, Kafka first studied [[chemistry]], but switched after two weeks to [[law]]. This offered a range of career possibilities, which pleased his father, and required a longer course of study that gave Kafka time to take classes in German studies and art history. At the [[university]], he joined a student club, named ''Lese- und Redehalle der Deutschen Studenten'', which organized literary events, readings and other activities. In the end of his first year of studies, he met [[Max Brod]], who would become a close friend throughout his life (and later his biographer), together with the journalist [[Felix Weltsch]], who also studied law. Kafka obtained his law degree on June 18, 1906, and performed an obligatory year of unpaid service as law clerk for the civil and criminal courts.<ref name="esp">Francesc Miralles Contijoch, ''Franz Kafka'' (Barcelona: Oceano Grupo Editorial, S.A., 2000, ISBN 8449418119). {{es icon}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Work=== | ||

| + | On November 1, 1907, he was hired at the Assicurazioni Generali, an aggressive Italian [[insurance]] company, where he worked for nearly a year. His correspondence during that period bears witness to his unhappiness with his work schedule—from 8 p.m. until 6 a.m.—as it made it extremely difficult for him to concentrate on his writing. | ||

| − | + | On July 15, 1908, he resigned, and two weeks later found more congenial employment with the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia. He often referred to his job as insurance officer as a ''Brotberuf'' (literally "bread job"), a job done only to pay the bills. However, as the several promotions that he received during his career prove, he was a hard working employee. He was given the task of compiling and composing the annual report and was reportedly quite proud of the results, sending copies to friends and family. Kafka was also committed to his literary work. Kafka and his close friends, Max Brod and Felix Weltsch, were called "Der enge Prager Kreis," “the close Prague circle.” | |

| − | |||

In 1911, Karl Hermann, spouse of his sister Elli, proposed Kafka collaborate in the operation of a factory of [[asbestos]], known as Prager Asbestwerke Hermann and Co. Kafka showed a positive attitude at first, dedicating much of his free time to the business. During that period, he also found interest and entertainment in the performances of Yiddish theater, despite the misgivings of even close friends such as Max Brod, who usually supported him in everything else. Those performances also served as a starting point for his growing relationship with [[Judaism]]. | In 1911, Karl Hermann, spouse of his sister Elli, proposed Kafka collaborate in the operation of a factory of [[asbestos]], known as Prager Asbestwerke Hermann and Co. Kafka showed a positive attitude at first, dedicating much of his free time to the business. During that period, he also found interest and entertainment in the performances of Yiddish theater, despite the misgivings of even close friends such as Max Brod, who usually supported him in everything else. Those performances also served as a starting point for his growing relationship with [[Judaism]]. | ||

| − | ===Later years=== | + | ===Later years=== |

| − | + | In 1912, at the home of his lifelong friend Max Brod, Kafka met Felice Bauer, who lived in [[Berlin]] and worked as a representative for a [[dictaphone]] company. Over the next five years they corresponded a great deal, met occasionally, and were engaged to be married twice. The relationship finally ended in 1917. | |

| − | In 1912, at the home of his lifelong friend Max Brod, Kafka met Felice Bauer, who lived in Berlin and worked as a representative for a dictaphone company. Over the next five years they corresponded a great deal, met occasionally, and were engaged to be married twice. The relationship finally ended in 1917. | + | |

| + | In 1917, he began to suffer from [[tuberculosis]], which would require frequent convalescence during which he was supported by his family, most notably his sister Ottla. Despite his fear of being perceived as both physically and mentally repulsive, he impressed others with his boyish, neat, and austere good looks, a quiet and cool demeanor, obvious intelligence and dry sense of humor.<ref>Ryan McKittrick, [http://www.amrep.org/articles/3_3c/disappearing.html “Disappearing Act,”] ''ARTicles'' 3(3) (June-July 2005). American Repertory Theatre. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | In | + | In the early 1920s he developed an intense relationship with Czech journalist and writer Milena Jesenská. In 1923 he briefly moved to Berlin in the hope of distancing himself from his family's influence to concentrate on his writing. In Berlin, he lived with Dora Diamant, a 25-year-old kindergarten teacher from an orthodox Jewish family, who was independent enough to have escaped her past in the [[ghetto]]. Dora became his lover, and influenced Kafka's interest in the [[Talmud]]. |

| − | + | It is generally agreed that Kafka suffered from [[Depression (psychology)|clinical depression]] and social anxiety throughout his entire life; he also suffered from [[migraine]]s, [[insomnia]], constipation, boils, and other ailments, all usually brought on by excessive [[stress (medicine)|stress]]. He attempted to counteract all of this by a regimen of [[Naturopathic Medicine|naturopathic]] treatments, such as a [[Vegetarianism|vegetarian]] diet and the consumption of large quantities of [[pasteurization|unpasteurized]] [[milk]] (the latter possibly was the cause of his [[tuberculosis]]).<ref> Public Library of Science, [http://www.brightsurf.com/news/headlines/view.article.php?ArticleID=20653 “Researchers discover ancient origins of tuberculosis-causing bacteria.”] Available online from BrightSurf. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | When Kafka's tuberculosis worsened, he returned to [[Prague]], then went to a [[sanatorium]] near [[Vienna]] for treatment, where he died on June 3, 1924, apparently from [[starvation]]. The condition of Kafka's throat made it too painful to eat, and since intravenous therapy had not been developed, there was no way to feed him (a fate ironically resembling that of Gregor in the ''Metamorphosis'' as well as the protagonist of ''A Hunger Artist''). His body was ultimately brought back to Prague where he was interred on June 11, 1924, in the New Jewish Cemetery in Žižkov. | |

==Literary work== | ==Literary work== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | |

| − | [[Image:Kafka | + | [[Image:Kafka monument.jpg|right|200px|thumb|Bronze statue of Franz Kafka in Prague]] |

| − | Kafka published only a few short stories during his lifetime | + | [[Image:Grave of Kafka.JPG|thumb|200px|Franz Kafka's grave in Prague-Žižkov]] |

| + | Kafka published only a few [[short story|short stories]] during his lifetime—a small part of his work—and never finished any of his [[novel]]s (with the possible exception of ''The Metamorphosis'', which some consider to be a short novel). His writing attracted little attention until after his death. Prior to his death, he instructed his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to destroy all of his manuscripts. His lover, Dora Diamant, partially executed his wishes, secretly keeping up to 20 notebooks and 35 letters until they were confiscated by the [[Gestapo]] in 1933. An ongoing international search is being conducted for these missing Kafka papers. Brod overrode Kafka's instructions and instead oversaw the publication of most of his work in his possession, which soon began to attract attention and high critical regard. | ||

All his published works, except several Czech letters to Milena Jesenská, were written in German. | All his published works, except several Czech letters to Milena Jesenská, were written in German. | ||

| + | ===Critical interpretation=== | ||

| + | Kafka's works have lent themselves to every manner of critical interpretation, such as [[modernism]] and [[magical realism]].<ref name=interpretation>[http://www.coskunfineart.com/details.asp?workID=40 Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century Portfolio: Franz Kafka,] Coskun Fine Art. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> The apparent hopelessness and the absurdity that seem to permeate his works have been considered emblematic of [[existentialism]]. Others have tried to locate a [[Marxism|Marxist]] influence in his satirization of [[bureaucracy]] in pieces such as ''In the Penal Colony'', ''The Trial'', and ''The Castle'',<ref name=interpretation/> while still others point to [[anarchism]] as an inspiration for Kafka's anti-bureaucratic viewpoint. Other interpretative frameworks abound. These include Judaism ([[Jorge Louis Borges]] made a few perceptive remarks in this regard), through [[psychoanalysis|Freudianism]]<ref name=interpretation/> (because of his familial struggles), or as allegories of a metaphysical quest for [[God]] ([[Thomas Mann]] was a proponent of this theory). | ||

| − | + | Themes of alienation and persecution are repeatedly emphasized, forming the basis for the analysis of critics like [[Marthe Robert]]. On the other hand, [[Gilles Deleuze]] and [[Felix Guattari]] argue that there was much more to Kafka than the stereotype of an anguished artist sharing his private sufferings. They argue that his work was more deliberate, subversive, and more "joyful" than it appears to many. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | There is some justification for this view in the anecdotes of Kafka reading passages to his friends while laughing boisterously. [[Milan Kundera]] attributes to the essentially [[surrealism|surrealist]] humor of Kafka the inspiration for later artists such as [[Federico Fellini]], [[Gabriel García Márquez]], [[Carlos Fuentes]] and [[Salman Rushdie]]. For Márquez it was the reading of Kafka's ''The Metamorphosis'' that showed him "that it was possible to write in a different way." | ||

| − | + | ===Writings and translations=== | |

| + | Readers of Kafka should pay particular attention to the dates of the publications (whether German or translated) of his writing when choosing an edition to read. Following is a brief history to assist the reader in understanding the editions. | ||

| − | + | Kafka died before preparing (in some cases even finishing) some of his writings for publication. Therefore, the novels ''The Castle'' (which stopped mid-sentence and had ambiguity on content), ''The Trial'' (chapters were unnumbered and some were incomplete) and ''Amerika'' (Kafka's original title was ''The Man who Disappeared'') were all prepared for publishing by [[Max Brod]]. It appears Brod took a few liberties with the manuscript (moving chapters, changing the German and cleaning up the punctuation) and hence the original German text, that was not published, was altered. The editions by Brod are generally referred to as the “definitive editions.” | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | According to the publisher's note for ''The Castle'' (Schocken Books, 1998),<ref>Arthur Samuelson, [http://www.jhom.com/bookshelf/kafka/intro.html “A Kafka For The 21st Century,”] ''Jewish Heritage Online Magazine''. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> Malcolm Pasley was able to get most of the Kafka's original handwritten work into the [[University of Oxford|Oxford]] Bodleian Library in 1961. The text for ''The Trial'' was later acquired through auction and is stored at the German literary archives at Marbach, Germany.<ref>“Publisher's Note,” ''The Trial'' (Schocken Books, 1998).</ref> |

| − | + | Subsequently, Malcolm Pasley headed a team (including Gerhard Neumann, Jost Schillemeit, and Jürgen Born) in reconstructing the German novels and ''S. Fischer Verlag'' republished them.<ref name="Adler_oct131995">Jeremy Adler, [http://www.textkritik.de/rezensionen/kafka/einl_04.htm “Stepping into Kafka’s Head,”] ''Times Literary Supplement'' (Oct. 13, 1995).</ref> Pasley was the editor for ''Das Schloβ'' (The Castle), published in 1982, and ''Der Prozeβ'' (The Trial), published in 1990. [[Jost Schillemeit]] was the editor of ''Der Verschollene'' ''(Amerika)'' published in 1983. These are all called the critical editions or the “Fischer Editions.” The German critical text of these, and Kafka's other works, may be found online at ''The Kafka Project''.<ref>Mauro Nervi, [http://www.kafka.org/index.php?project The Kafka Project - Kafka's Works in German According to the Manuscript.] Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===The Metamorphosis=== | |

| + | ''The Metamorphosis'' (in [[German language|German]], ''Die Verwandlung'') is Kafka's most famous work, first published in 1915. Shown here is the cover of the first edition. The story begins with a traveling salesman, Gregor Samsa, waking to find himself transformed into a giant "monstrous vermin" (see [[#Lost in translation|Lost in translation]], below). | ||

| − | + | ====Plot summary==== | |

| + | The story is a tragic [[comedy]], with the ridiculousness of the circumstance creating moments of great hilarity and pathos—sometimes both together. At the beginning of the story, Gregor's main concern is that despite his new condition, he must nevertheless get to work on time. | ||

| − | + | Gregor is unable to speak in his new form, and never successfully communicates with his family at all after his physical appearance is revealed to them. However, he seems to retain his cognitive faculties, which is unknown to his family. | |

| − | + | Curiously, his condition does not arouse a sense of surprise or incredulity in the eyes of his family, who merely despise it as an indication of impending burden. However, most of the story revolves around his interactions with his family, with whom he lives, and their shock, denial, and repulsion whenever he reveals his physical condition. Horrified by his appearance, they take to shutting Gregor into his room, but do try to care for him by providing him food and water. The sister takes charge of caring for Gregor, initially working hard to make him comfortable. Nevertheless, they seem to want as little to do with him as possible. The sister and mother shrink back whenever he reveals himself, and Gregor's father pelts him with apples when he emerges from his room one day. One of the apples becomes embedded in his back, causing an infection. | |

| − | + | As time passes with Gregor confined to his room, his only activities are looking out of his window, and crawling up the walls and over the ceiling. Financial hardship befalls the family, and the sister's caretaking deteriorates. Devoid of human contact, one day Gregor emerges to the sound of his sister's [[violin]] in the hopes to get his much-loved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. But her rejection of him is total, when she says to the family: “We must try to get rid of it. We've done everything humanly possible to take care of it and to put up with it, no one can blame us in the least.” | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The sister then determines with finality that the creature is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. Gregor returns to his room, lies down, and dies from starvation, neglect and infection caused by the festering apple his father threw at him months before. | |

| − | + | The point of view shifts as, upon discovery of his corpse, the family feel an enormous burden has been lifted from them, and start planning for the future again. Fantastically, the family suddenly discovers that they aren't doing badly at all, both socially and financially, and the brief process of forgetting Gregor and shutting him from their lives is quickly accomplished. | |

| − | + | ====Interpretation==== | |

| + | As with all of Kafka's works, ''The Metamorphosis'' is open to a wide range of interpretations; in fact, Stanley Corngold's book, ''The Commentator's Despair'', lists over 130 interpretations. Most obvious are themes relating to society's treatment of those who are different and the effect of [[bourgeois]] society and [[bureaucracy]] on the human spirit and the loneliness and isolation of the individual in modern society. [[Food]] plays an ambiguous role as both the source of sustenance but also as [[weapon]] and instrument of death. | ||

| − | ==Lost in translation== | + | ====Lost in translation==== |

| − | The | + | The opening line of the novella is famous in English: |

| − | : | + | :As Gregor Samsa woke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself in his bed, transformed into a monstrous insect. |

The original German line runs like this: | The original German line runs like this: | ||

| − | : | + | :Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | English translators have often sought to render the word ''Ungeziefer'' as "insect," but this is not strictly accurate, and may be based on an attempt to clarify what Kafka may have intended (according to his journals and letters to the publisher of the text) to be an ambiguous term. In German, ''Ungeziefer'' literally means "vermin" and is sometimes used to mean "bug"—a very general term, totally unlike the scientific sounding "insect." Kafka had no intention of labeling Gregor as this or that specific thing, but merely wanted to convey disgust in his transformation. Literally, the end of the line should be translated as ''...transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin'' (this is the phrasing used in the David Wyllie translation,<ref>Franz Kafka, ''Metamorphosis'', trans. David Wyllie. [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/5200 Available online] from Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> although the feeling of the word in German is more colloquial sounding (like "bug"). | |

| − | + | However, "a monstrous vermin" sounds unwieldy in English and in Kafka's letter to his publisher of October 25, 1915, in which he discusses his concern about the cover illustration for the first edition, he uses the term "Insekt," saying "The insect itself is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance."<ref>[http://www.literature.at/elib/www/wiki/index.php/Briefe_und_Tageb%C3%BCcher_1915_%28Franz_Kafka%29#1915-10-11.2C_Prag:_An_den_Kurt_Wolff_Verlag_.28G.H.Meyer.29 “Briefe und Tagebücher 1915 (Franz Kafka),”] eLib.at. Retrieved September 12, 2007. {{de icon}}</ref> | |

| − | + | While this shows his concern not to give precise information about the type of creature Gregor becomes, the use of the general term "insect" can therefore be defended on the part of translators wishing to improve the readability of the end text. | |

| − | + | ''Ungeziefer'' has sometimes been rendered as "[[cockroach]]," "[[dung beetle]]," "[[beetle]]," and other highly specific terms. The only term in the book is "dung beetle," used by the cleaning lady near the end of the story, but it is not used in the narration. This has become such a common misconception, that English speakers will often summarize ''Metamorphosis'' as "...a story about a guy who turns into a cockroach." Despite all this, no such creature appears in the original text. | |

| − | + | [[Vladimir Nabokov]], who was an [[entomologist]] as well as writer and literary critic, insisted that Gregor was ''not'' a cockroach, but a beetle with wings under his shell, and capable of flight - if only he had known it. He left a sketch annotated "just over three feet long" on the opening page of his (heavily corrected) English teaching copy.<ref> First Page of Vladimir Nabokov’s Teaching Copy, Leni's Franz Kafka Page.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | + | Kafka was one of the most important writers of the twentieth century. His influence has been widely felt across a spectrum of writers from different nationalities. The term "kafkaesque" was created to describe the kind of nightmarish situations like those faced by Josef K., the hero of his novel ''The Trial'', who finds himself the victim of the bizarre logic of an inexorible court judgment. [[Magic realism]] in particular owes a great deal to Kafka, but almost every modernist and post-modernist writer has been influenced by the menacing atmosphere of his works. | |

| − | ====Literature==== | + | ====References in Other Literature==== |

| − | *In [[Kurt Vonnegut]]'s collection of short essays " | + | *In [[Kurt Vonnegut]]'s collection of short essays "A Man Without a Country," he mentions "The Metamorphosis" in a discussion of plot as an example of a book where the main character starts out in a bad situation and it only gets worse from there (to infinity, in fact). |

| − | *[[Philip Roth]]'s novel '' | + | *[[Philip Roth]]'s novel ''The Breast'' (1972) was partially inspired by Kafka's tale. |

| − | *In [[Rudy Rucker]]'s novel '' | + | *In [[Rudy Rucker]]'s novel ''White Light'', the main character enters a world where he meets a giant talking roach-like creature named "Franx." |

*Catalan writer [[Quim Monzo]]'s rather twisted short story ''Gregor'' tells about a bug which turns into a human, in an attempt to ironically deconstruct ''The Metamorphosis.'' | *Catalan writer [[Quim Monzo]]'s rather twisted short story ''Gregor'' tells about a bug which turns into a human, in an attempt to ironically deconstruct ''The Metamorphosis.'' | ||

| − | == | + | ==Major Works== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Short stories=== | ===Short stories=== | ||

| − | * '' | + | * ''Description of a Struggle'' (''Beschreibung eines Kampfes''; 1904-1905) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Wedding Preparations in the Country'' (''Hochzeitsvorbereitungen auf dem Lande''; 1907-1908) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Judgment'' (''Das Urteil''; September 22-23, 1912) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''In the Penal Colony'' (''In der Strafkolonie''; October 1914) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Village Schoolmaster (The Giant Mole)'' (''Der Dorfschullehrer'' or ''Der Riesenmaulwurf''; 1914-1915) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Blumfeld, an Elderly Bachelor'' (''Blumfeld, ein älterer Junggeselle''; 1915) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Warden of the Tomb'' (''Der Gruftwächter''; 1916-1917) – the only play Kafka wrote |

| − | * '' | + | * ''A Country Doctor'' (''Ein Landarzt''; 1917) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Hunter Gracchus'' (''Der Jäger Gracchus''; 1917) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Great Wall of China'' (''Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer''; 1917) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''A Report to an Academy'' (''Ein Bericht für eine Akademie''; 1917) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Refusal'' (''Die Abweisung''; 1920) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''A Hunger Artist'' (''Ein Hungerkünstler''; 1922) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Investigations of a Dog'' (''Forschungen eines Hundes''; 1922) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''A Little Woman'' (''Eine kleine Frau''; 1923) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Burrow'' (''Der Bau''; 1923-1924) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Josephine the Singer, or The Mouse Folk'' (''Josephine, die Sängerin, oder Das Volk der Mäuse''; 1924) |

Many collections of the stories have been published, and they include: | Many collections of the stories have been published, and they include: | ||

| − | * | + | * ''The Complete Stories.'' Edited by Nahum N. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books, 1971. |

===Novellas=== | ===Novellas=== | ||

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Metamorphosis'' (''Die Verwandlung''; November-December 1915) |

===Novels=== | ===Novels=== | ||

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Trial'' (''Der Prozeß'', 1925; includes short story “Before the Law”) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Castle'' (''Das Schloß''; 1926) |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Amerika'' (1927) |

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | *'' | + | *Brod, Max. ''Franz Kafka: A Biography.'' New York: Da Capo Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0306806704 |

| − | *'' | + | *Brod, Max. ''The Biography of Franz Kafka''. Trans. by G. Humphreys Roberts. London: Secker & Warburg, 1947. ISBN 978-0306806704 |

| − | *'' | + | * Citati, Pietro. ''Kafka''. Gallimard, 1987. ISBN 978-2070384174 |

| − | *'' | + | * Contijoch, Francesc Miralles. ''Franz Kafka''. Barcelona: Oceano Grupo Editorial, S.A., 2000. ISBN 8449418119 |

| − | *''Franz Kafka: | + | *Corngold, Stanley. Introduction to ''The Metamorphosis''. Reissue edition, 1972. New York: Bantam Classics. ISBN 0553213695 |

| + | * Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. ''Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature'' (Theory and History of Literature, vol. 30). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1986. ISBN 978-0816615155 | ||

| + | * Gilman, Sander L. ''Franz Kafka''. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1861892543 | ||

| + | *Greenberg, Martin. ''The Terror of Art: Kafka and Modern Literature''. New York, Basic Books, 1968. ISBN 978-0465084159 | ||

| + | *Hayman, Ronald. ''K, a Biography of Kafka''. London: Phoenix Press, 2001. ISBN 9781842124154 | ||

| + | *Janouch, Gustav. ''Conversations with Kafka'', 2nd ed. Trans. by Goronwy Rees. New York: New Directions Books, 1971. ISBN 978-0811200714 | ||

| + | *Mairowitz, David Zane, and Robert Crumb. ''Introducing Kafka''. New York: Totem Books, 1993. ISBN 978-1840461220 | ||

| + | *Murray, Nicholas. ''Kafka.'' New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 0300106319 | ||

| + | *Pawel, Ernst. ''The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka.'' New York: Vintage Books, 1985. ISBN 0374222363 | ||

| + | *Thiher, Allen (ed.). ''Franz Kafka: A Study of the Short Fiction'' (Twayne's Studies in Short Fiction, No. 12). New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990. ISBN 978-0805783230 | ||

| − | === | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved April 11, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* {{gutenberg author| id=Franz+Kafka | name=Franz Kafka}} | * {{gutenberg author| id=Franz+Kafka | name=Franz Kafka}} | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.kafka.org/ The Kafka Project] | |

| − | + | *[http://www.kafkasocietyofamerica.org/ The Kafka Society of America] | |

| − | + | * [http://www.levity.com/corduroy/kafka.htm Franz Kafka (1883-1924)] – Bohemian Ink | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.kafka.org/ The Kafka Project] | ||

| − | *[http://www.kafkasocietyofamerica.org/ The Kafka Society | ||

| − | * [http://www.levity.com/corduroy/kafka.htm Franz Kafka (1883-1924)] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] |

| − | {{credit2| | + | [[Category:Literature]] |

| + | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| + | {{credit2|Franz_Kafka|80484502|The_Metamorphosis|80962094}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:35, 11 April 2024

Photograph of Franz Kafka taken in 1917 | |

| Born: | July 3, 1883 Prague, Austria-Hungary (today in the Czech Republic) |

|---|---|

| Died: | June 3, 1924 Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation(s): | insurance officer, factory manager, novelist, short story writer |

| Nationality: | Ashkenazi Jewish-Bohemian (Austria-Hungary) |

| Literary genre: | novel, short story |

| Literary movement: | modernism, existentialism, Surrealism, precursor to magical realism |

| Influences: | Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Charles Dickens, Nietzsche |

| Influenced: | Albert Camus, Federico Fellini, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, Salman Rushdie, Haruki Murakami |

Franz Kafka (July 3, 1883 – June 3, 1924) was one of the major German language novelists and short story writers of the twentieth century, whose unique body of writing—much of it incomplete and published posthumously despite his wish that it be destroyed—has become iconic in Western literature.

His most famous pieces of writing include his short story Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis) and his two novels, Der Prozess (The Trial) and the unfinished novel Das Schloß (The Castle). Kafka's work expresses the essential absurdity of modern society, especially the impersonal nature of bureaucracy and capitalism. The individual in Kafka's texts is alone and at odds with the society around him, which seems to operate in a secretive manner that the individual cannot understand. Kafka's world is one in which God is dead and the individual is "on trial," as the name of his most famous novel suggests. It is a world devoid of meaning or purpose other than to clear one's name of the nebulous sense of guilt that pervades the atmosphere. The adjective "Kafkaesque" has come into common use to denote mundane yet absurd and surreal circumstances of the kind commonly found in Kafka's work.

Kafka's work represents an extreme example of the modern concern with the individual's place in society. As modernity displaced people from traditional society's fixed meanings and family networks, Kafka exposes the emptiness and even perniciousness of a world in which meaning is not only absent, but malevolent toward the individual. Lacking a transcendent source of value, society is not a hospitable place and meaning is menacing.

Life

Family

Kafka was born into a middle-class, German-speaking Jewish family in Prague, then capital of Bohemia, a kingdom that was then part of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. His father, Hermann Kafka (1852–1931), was described as a "huge, selfish, overbearing businessman"[1] and by Kafka himself as "a true Kafka in strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction, worldly dominance, endurance, presence of mind, [and] knowledge of human nature..."[2]

Kafka struggled to come to terms with his domineering father. Hermann was the fourth child of Jacob Kafka, a butcher, and came to Prague from Osek, a Jewish village near Písek in southern Bohemia. After working as a traveling sales representative, he established himself as an independent retailer of men's and women's fancy goods and accessories, employing up to 15 people and using a jackdaw (kavka in Czech) as his business logo. Kafka's mother, Julie (1856—1934), was the daughter of Jakob Löwy, a prosperous brewer in Poděbrady, and was better educated than her husband.[3]

Kafka had two younger brothers, Georg and Heinrich, who died at the ages of 15 months and six months, respectively, and three younger sisters, Gabriele ("Elli") (1889–1941), Valerie ("Valli") (1890–1942), and Ottilie ("Ottla") (1892–1943). On business days, both parents were absent from the home. His mother helped to manage her husband's business and worked in it as much as 12 hours a day. The children were largely reared by a succession of governesses and servants.

During World War II, Kafka's sisters were sent with their families to the Łódź ghetto and died there or in concentration camps. Ottla is believed to have been sent to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt and then to the death camp at Auschwitz.

Education

Kafka learned German as his first language, but he was also almost fluent in Czech. Later, Kafka also acquired some knowledge of the French language and culture; one of his favorite authors was Gustave Flaubert. From 1889 to 1893, he attended the Deutsche Knabenschule, the boys' elementary school at the Fleischmarkt (meat market), the street now known as Masná Street in Prague. His Jewish education was limited to his Bar Mitzvah celebration at 13 and going to the synagogue four times a year with his father.[4] After elementary school, he was admitted to the rigorous classics-oriented state gymnasium, Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, an academic secondary school with eighth grade levels, where German was also the language of instruction, at Staroměstské náměstí, within the Kinsky Palace in the Old Town. He completed his Matura exams in 1901.

Admitted to the Charles University of Prague, Kafka first studied chemistry, but switched after two weeks to law. This offered a range of career possibilities, which pleased his father, and required a longer course of study that gave Kafka time to take classes in German studies and art history. At the university, he joined a student club, named Lese- und Redehalle der Deutschen Studenten, which organized literary events, readings and other activities. In the end of his first year of studies, he met Max Brod, who would become a close friend throughout his life (and later his biographer), together with the journalist Felix Weltsch, who also studied law. Kafka obtained his law degree on June 18, 1906, and performed an obligatory year of unpaid service as law clerk for the civil and criminal courts.[5]

Work

On November 1, 1907, he was hired at the Assicurazioni Generali, an aggressive Italian insurance company, where he worked for nearly a year. His correspondence during that period bears witness to his unhappiness with his work schedule—from 8 p.m. until 6 a.m.—as it made it extremely difficult for him to concentrate on his writing.

On July 15, 1908, he resigned, and two weeks later found more congenial employment with the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia. He often referred to his job as insurance officer as a Brotberuf (literally "bread job"), a job done only to pay the bills. However, as the several promotions that he received during his career prove, he was a hard working employee. He was given the task of compiling and composing the annual report and was reportedly quite proud of the results, sending copies to friends and family. Kafka was also committed to his literary work. Kafka and his close friends, Max Brod and Felix Weltsch, were called "Der enge Prager Kreis," “the close Prague circle.”

In 1911, Karl Hermann, spouse of his sister Elli, proposed Kafka collaborate in the operation of a factory of asbestos, known as Prager Asbestwerke Hermann and Co. Kafka showed a positive attitude at first, dedicating much of his free time to the business. During that period, he also found interest and entertainment in the performances of Yiddish theater, despite the misgivings of even close friends such as Max Brod, who usually supported him in everything else. Those performances also served as a starting point for his growing relationship with Judaism.

Later years

In 1912, at the home of his lifelong friend Max Brod, Kafka met Felice Bauer, who lived in Berlin and worked as a representative for a dictaphone company. Over the next five years they corresponded a great deal, met occasionally, and were engaged to be married twice. The relationship finally ended in 1917.

In 1917, he began to suffer from tuberculosis, which would require frequent convalescence during which he was supported by his family, most notably his sister Ottla. Despite his fear of being perceived as both physically and mentally repulsive, he impressed others with his boyish, neat, and austere good looks, a quiet and cool demeanor, obvious intelligence and dry sense of humor.[6]

In the early 1920s he developed an intense relationship with Czech journalist and writer Milena Jesenská. In 1923 he briefly moved to Berlin in the hope of distancing himself from his family's influence to concentrate on his writing. In Berlin, he lived with Dora Diamant, a 25-year-old kindergarten teacher from an orthodox Jewish family, who was independent enough to have escaped her past in the ghetto. Dora became his lover, and influenced Kafka's interest in the Talmud.

It is generally agreed that Kafka suffered from clinical depression and social anxiety throughout his entire life; he also suffered from migraines, insomnia, constipation, boils, and other ailments, all usually brought on by excessive stress. He attempted to counteract all of this by a regimen of naturopathic treatments, such as a vegetarian diet and the consumption of large quantities of unpasteurized milk (the latter possibly was the cause of his tuberculosis).[7]

When Kafka's tuberculosis worsened, he returned to Prague, then went to a sanatorium near Vienna for treatment, where he died on June 3, 1924, apparently from starvation. The condition of Kafka's throat made it too painful to eat, and since intravenous therapy had not been developed, there was no way to feed him (a fate ironically resembling that of Gregor in the Metamorphosis as well as the protagonist of A Hunger Artist). His body was ultimately brought back to Prague where he was interred on June 11, 1924, in the New Jewish Cemetery in Žižkov.

Literary work

Kafka published only a few short stories during his lifetime—a small part of his work—and never finished any of his novels (with the possible exception of The Metamorphosis, which some consider to be a short novel). His writing attracted little attention until after his death. Prior to his death, he instructed his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to destroy all of his manuscripts. His lover, Dora Diamant, partially executed his wishes, secretly keeping up to 20 notebooks and 35 letters until they were confiscated by the Gestapo in 1933. An ongoing international search is being conducted for these missing Kafka papers. Brod overrode Kafka's instructions and instead oversaw the publication of most of his work in his possession, which soon began to attract attention and high critical regard.

All his published works, except several Czech letters to Milena Jesenská, were written in German.

Critical interpretation

Kafka's works have lent themselves to every manner of critical interpretation, such as modernism and magical realism.[8] The apparent hopelessness and the absurdity that seem to permeate his works have been considered emblematic of existentialism. Others have tried to locate a Marxist influence in his satirization of bureaucracy in pieces such as In the Penal Colony, The Trial, and The Castle,[8] while still others point to anarchism as an inspiration for Kafka's anti-bureaucratic viewpoint. Other interpretative frameworks abound. These include Judaism (Jorge Louis Borges made a few perceptive remarks in this regard), through Freudianism[8] (because of his familial struggles), or as allegories of a metaphysical quest for God (Thomas Mann was a proponent of this theory).

Themes of alienation and persecution are repeatedly emphasized, forming the basis for the analysis of critics like Marthe Robert. On the other hand, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari argue that there was much more to Kafka than the stereotype of an anguished artist sharing his private sufferings. They argue that his work was more deliberate, subversive, and more "joyful" than it appears to many.

There is some justification for this view in the anecdotes of Kafka reading passages to his friends while laughing boisterously. Milan Kundera attributes to the essentially surrealist humor of Kafka the inspiration for later artists such as Federico Fellini, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Salman Rushdie. For Márquez it was the reading of Kafka's The Metamorphosis that showed him "that it was possible to write in a different way."

Writings and translations

Readers of Kafka should pay particular attention to the dates of the publications (whether German or translated) of his writing when choosing an edition to read. Following is a brief history to assist the reader in understanding the editions.

Kafka died before preparing (in some cases even finishing) some of his writings for publication. Therefore, the novels The Castle (which stopped mid-sentence and had ambiguity on content), The Trial (chapters were unnumbered and some were incomplete) and Amerika (Kafka's original title was The Man who Disappeared) were all prepared for publishing by Max Brod. It appears Brod took a few liberties with the manuscript (moving chapters, changing the German and cleaning up the punctuation) and hence the original German text, that was not published, was altered. The editions by Brod are generally referred to as the “definitive editions.”

According to the publisher's note for The Castle (Schocken Books, 1998),[9] Malcolm Pasley was able to get most of the Kafka's original handwritten work into the Oxford Bodleian Library in 1961. The text for The Trial was later acquired through auction and is stored at the German literary archives at Marbach, Germany.[10]

Subsequently, Malcolm Pasley headed a team (including Gerhard Neumann, Jost Schillemeit, and Jürgen Born) in reconstructing the German novels and S. Fischer Verlag republished them.[11] Pasley was the editor for Das Schloβ (The Castle), published in 1982, and Der Prozeβ (The Trial), published in 1990. Jost Schillemeit was the editor of Der Verschollene (Amerika) published in 1983. These are all called the critical editions or the “Fischer Editions.” The German critical text of these, and Kafka's other works, may be found online at The Kafka Project.[12]

The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis (in German, Die Verwandlung) is Kafka's most famous work, first published in 1915. Shown here is the cover of the first edition. The story begins with a traveling salesman, Gregor Samsa, waking to find himself transformed into a giant "monstrous vermin" (see Lost in translation, below).

Plot summary

The story is a tragic comedy, with the ridiculousness of the circumstance creating moments of great hilarity and pathos—sometimes both together. At the beginning of the story, Gregor's main concern is that despite his new condition, he must nevertheless get to work on time.

Gregor is unable to speak in his new form, and never successfully communicates with his family at all after his physical appearance is revealed to them. However, he seems to retain his cognitive faculties, which is unknown to his family.

Curiously, his condition does not arouse a sense of surprise or incredulity in the eyes of his family, who merely despise it as an indication of impending burden. However, most of the story revolves around his interactions with his family, with whom he lives, and their shock, denial, and repulsion whenever he reveals his physical condition. Horrified by his appearance, they take to shutting Gregor into his room, but do try to care for him by providing him food and water. The sister takes charge of caring for Gregor, initially working hard to make him comfortable. Nevertheless, they seem to want as little to do with him as possible. The sister and mother shrink back whenever he reveals himself, and Gregor's father pelts him with apples when he emerges from his room one day. One of the apples becomes embedded in his back, causing an infection.

As time passes with Gregor confined to his room, his only activities are looking out of his window, and crawling up the walls and over the ceiling. Financial hardship befalls the family, and the sister's caretaking deteriorates. Devoid of human contact, one day Gregor emerges to the sound of his sister's violin in the hopes to get his much-loved sister to join him in his room and play her violin for him. But her rejection of him is total, when she says to the family: “We must try to get rid of it. We've done everything humanly possible to take care of it and to put up with it, no one can blame us in the least.”

The sister then determines with finality that the creature is no longer Gregor, since Gregor would have left them out of love and taken their burden away. Gregor returns to his room, lies down, and dies from starvation, neglect and infection caused by the festering apple his father threw at him months before.

The point of view shifts as, upon discovery of his corpse, the family feel an enormous burden has been lifted from them, and start planning for the future again. Fantastically, the family suddenly discovers that they aren't doing badly at all, both socially and financially, and the brief process of forgetting Gregor and shutting him from their lives is quickly accomplished.

Interpretation

As with all of Kafka's works, The Metamorphosis is open to a wide range of interpretations; in fact, Stanley Corngold's book, The Commentator's Despair, lists over 130 interpretations. Most obvious are themes relating to society's treatment of those who are different and the effect of bourgeois society and bureaucracy on the human spirit and the loneliness and isolation of the individual in modern society. Food plays an ambiguous role as both the source of sustenance but also as weapon and instrument of death.

Lost in translation

The opening line of the novella is famous in English:

- As Gregor Samsa woke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself in his bed, transformed into a monstrous insect.

The original German line runs like this:

- Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt.

English translators have often sought to render the word Ungeziefer as "insect," but this is not strictly accurate, and may be based on an attempt to clarify what Kafka may have intended (according to his journals and letters to the publisher of the text) to be an ambiguous term. In German, Ungeziefer literally means "vermin" and is sometimes used to mean "bug"—a very general term, totally unlike the scientific sounding "insect." Kafka had no intention of labeling Gregor as this or that specific thing, but merely wanted to convey disgust in his transformation. Literally, the end of the line should be translated as ...transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin (this is the phrasing used in the David Wyllie translation,[13] although the feeling of the word in German is more colloquial sounding (like "bug").

However, "a monstrous vermin" sounds unwieldy in English and in Kafka's letter to his publisher of October 25, 1915, in which he discusses his concern about the cover illustration for the first edition, he uses the term "Insekt," saying "The insect itself is not to be drawn. It is not even to be seen from a distance."[14]

While this shows his concern not to give precise information about the type of creature Gregor becomes, the use of the general term "insect" can therefore be defended on the part of translators wishing to improve the readability of the end text.

Ungeziefer has sometimes been rendered as "cockroach," "dung beetle," "beetle," and other highly specific terms. The only term in the book is "dung beetle," used by the cleaning lady near the end of the story, but it is not used in the narration. This has become such a common misconception, that English speakers will often summarize Metamorphosis as "...a story about a guy who turns into a cockroach." Despite all this, no such creature appears in the original text.

Vladimir Nabokov, who was an entomologist as well as writer and literary critic, insisted that Gregor was not a cockroach, but a beetle with wings under his shell, and capable of flight - if only he had known it. He left a sketch annotated "just over three feet long" on the opening page of his (heavily corrected) English teaching copy.[15]

Legacy

Kafka was one of the most important writers of the twentieth century. His influence has been widely felt across a spectrum of writers from different nationalities. The term "kafkaesque" was created to describe the kind of nightmarish situations like those faced by Josef K., the hero of his novel The Trial, who finds himself the victim of the bizarre logic of an inexorible court judgment. Magic realism in particular owes a great deal to Kafka, but almost every modernist and post-modernist writer has been influenced by the menacing atmosphere of his works.

References in Other Literature

- In Kurt Vonnegut's collection of short essays "A Man Without a Country," he mentions "The Metamorphosis" in a discussion of plot as an example of a book where the main character starts out in a bad situation and it only gets worse from there (to infinity, in fact).

- Philip Roth's novel The Breast (1972) was partially inspired by Kafka's tale.

- In Rudy Rucker's novel White Light, the main character enters a world where he meets a giant talking roach-like creature named "Franx."

- Catalan writer Quim Monzo's rather twisted short story Gregor tells about a bug which turns into a human, in an attempt to ironically deconstruct The Metamorphosis.

Major Works

Short stories

- Description of a Struggle (Beschreibung eines Kampfes; 1904-1905)

- Wedding Preparations in the Country (Hochzeitsvorbereitungen auf dem Lande; 1907-1908)

- The Judgment (Das Urteil; September 22-23, 1912)

- In the Penal Colony (In der Strafkolonie; October 1914)

- The Village Schoolmaster (The Giant Mole) (Der Dorfschullehrer or Der Riesenmaulwurf; 1914-1915)

- Blumfeld, an Elderly Bachelor (Blumfeld, ein älterer Junggeselle; 1915)

- The Warden of the Tomb (Der Gruftwächter; 1916-1917) – the only play Kafka wrote

- A Country Doctor (Ein Landarzt; 1917)

- The Hunter Gracchus (Der Jäger Gracchus; 1917)

- The Great Wall of China (Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer; 1917)

- A Report to an Academy (Ein Bericht für eine Akademie; 1917)

- The Refusal (Die Abweisung; 1920)

- A Hunger Artist (Ein Hungerkünstler; 1922)

- Investigations of a Dog (Forschungen eines Hundes; 1922)

- A Little Woman (Eine kleine Frau; 1923)

- The Burrow (Der Bau; 1923-1924)

- Josephine the Singer, or The Mouse Folk (Josephine, die Sängerin, oder Das Volk der Mäuse; 1924)

Many collections of the stories have been published, and they include:

- The Complete Stories. Edited by Nahum N. Glatzer. New York: Schocken Books, 1971.

Novellas

- The Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung; November-December 1915)

Novels

- The Trial (Der Prozeß, 1925; includes short story “Before the Law”)

- The Castle (Das Schloß; 1926)

- Amerika (1927)

Notes

- ↑ Stanley Corngold, Introduction to The Metamorphosis (New York: Bantam Classics, reissue edition, 1972, ISBN 0553213695).

- ↑ Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins (trans.), “Franz Kafka's Letter to his father.” Available online from Franz Kafka Web Site by Daniel Hornek. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Sander L. Gilman, Franz Kafka (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005, ISBN 1861892543), 20-21.

- ↑ Daniel Hornek, Franz Kafka Biography, Franz Kafka Web Site. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Francesc Miralles Contijoch, Franz Kafka (Barcelona: Oceano Grupo Editorial, S.A., 2000, ISBN 8449418119). (Spanish)

- ↑ Ryan McKittrick, “Disappearing Act,” ARTicles 3(3) (June-July 2005). American Repertory Theatre. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Public Library of Science, “Researchers discover ancient origins of tuberculosis-causing bacteria.” Available online from BrightSurf. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century Portfolio: Franz Kafka, Coskun Fine Art. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Arthur Samuelson, “A Kafka For The 21st Century,” Jewish Heritage Online Magazine. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ “Publisher's Note,” The Trial (Schocken Books, 1998).

- ↑ Jeremy Adler, “Stepping into Kafka’s Head,” Times Literary Supplement (Oct. 13, 1995).

- ↑ Mauro Nervi, The Kafka Project - Kafka's Works in German According to the Manuscript. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Franz Kafka, Metamorphosis, trans. David Wyllie. Available online from Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ “Briefe und Tagebücher 1915 (Franz Kafka),” eLib.at. Retrieved September 12, 2007. (German)

- ↑ First Page of Vladimir Nabokov’s Teaching Copy, Leni's Franz Kafka Page.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brod, Max. Franz Kafka: A Biography. New York: Da Capo Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0306806704

- Brod, Max. The Biography of Franz Kafka. Trans. by G. Humphreys Roberts. London: Secker & Warburg, 1947. ISBN 978-0306806704

- Citati, Pietro. Kafka. Gallimard, 1987. ISBN 978-2070384174

- Contijoch, Francesc Miralles. Franz Kafka. Barcelona: Oceano Grupo Editorial, S.A., 2000. ISBN 8449418119

- Corngold, Stanley. Introduction to The Metamorphosis. Reissue edition, 1972. New York: Bantam Classics. ISBN 0553213695

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (Theory and History of Literature, vol. 30). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1986. ISBN 978-0816615155

- Gilman, Sander L. Franz Kafka. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2005. ISBN 1861892543

- Greenberg, Martin. The Terror of Art: Kafka and Modern Literature. New York, Basic Books, 1968. ISBN 978-0465084159

- Hayman, Ronald. K, a Biography of Kafka. London: Phoenix Press, 2001. ISBN 9781842124154

- Janouch, Gustav. Conversations with Kafka, 2nd ed. Trans. by Goronwy Rees. New York: New Directions Books, 1971. ISBN 978-0811200714

- Mairowitz, David Zane, and Robert Crumb. Introducing Kafka. New York: Totem Books, 1993. ISBN 978-1840461220

- Murray, Nicholas. Kafka. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 0300106319

- Pawel, Ernst. The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka. New York: Vintage Books, 1985. ISBN 0374222363

- Thiher, Allen (ed.). Franz Kafka: A Study of the Short Fiction (Twayne's Studies in Short Fiction, No. 12). New York: Twayne Publishers, 1990. ISBN 978-0805783230

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- Works by Franz Kafka. Project Gutenberg

- The Kafka Project

- The Kafka Society of America

- Franz Kafka (1883-1924) – Bohemian Ink

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.