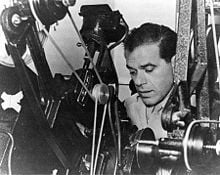

Frank Capra

| Frank Capra | |

| |

| Birth name: | Frank Rosario Capra |

|---|---|

| Date of birth: | May 18, 1897 |

| Birth location: | |

| Date of death: | September 3 1991 (aged 94) |

| Death location: | |

| Academy Awards: | Best Director Won: 1934 It Happened One Night 1936 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town 1938 You Can't Take It with You Nominated: 1933 Lady for a Day 1939 Mr. Smith Goes to Washington 1946 It's a Wonderful Life Best Picture Won: 1934 It Happened One Night 1938 You Can't Take It with You Nominated: 1936 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town 1937 Lost Horizon 1939 Mr. Smith Goes to Washington 1946 It's a Wonderful Life |

| Spouse: | Helen Howell (1923-1927) (divorced) Lou Capra (1932-1984) (her death) 3 children |

Frank Capra (May 18, 1897 – September 3, 1991) was an Academy Award winning Italian-American film director and and the creative force behind a string of popular films in the 1930s and 40s. He is most remembered for his "feel-good" movies where average men overcome great injustices, such as 1939's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and 1946's It's a Wonderful Life.

Early life

Frank Capra, born Francesco Rosario Capra on May 19, 1897 to Salvatore and Rosaria Nicolosi Capra in Bisacquino, Sicily. Capra, along with his parents and siblings, moved to L.A. in 1903 where his older brother Benjamin was already living. Here, Frank began his schooling at Casteler Elementary school and later Los Angeles' Manual Arts High School. Capra earned money through a number of menial jobs, including selling newspapers, working as a janitor, and playing in a two-man music combo at local brothels for a dollar a night. His real passion, though, was pursued during school hours as a participant in the theatre program, doing back-stage work such as lighting.

Capra's family would have rather had Frank drop out of school and go to work, but he was determined to get an education as part of his plan to fulfill the American dream. Capra graduated from high school in 1915, and later that same year entered the Throop College of Technology (later the California School of Technology) to study chemical engineering. It was here that he discovered the poetry and essays of Montaigne through the school's fine art department, developing a taste for language that would soon inspire him to try his hand at writing.

Despite the death of his father that year, Capra had the highest grades in his school and was awarded a $250 scholarship in addition to a six-week trip across the U.S. and Canada.

On April 6, 1917, after congress declared war on Germany Capra tried to enlist in the Army but was denied entrance as he had not yet become a naturalized citizen. Instead, he served in the Coastal Artillery, working as a supply officer for the student soldiers at Throop. On September 15, 1918, Capra graduated from Throop and one month later was inducted into the army, with orders to ship out to the Presidio at San Francisco. While there, Presidio was one of tens of millions of people worldwide that year to become ill with the Spanish Influenza. In November the war had ended, and in December Capra was discharged so that he could recover from his illness.

While recuperating, Frank responded to a casting call for extras for John Ford's film "The Outcasts of Poker Flat" (1919). He was given a part as a background laborer, and used this opportunity on set to introduce himself to the film's star, Harry Carey, who Capra would later go on to cast in "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" two decades later.

In his post-collegiate years, Capra worked a variety of odd jobs, including errand boy, ditch digger, live-in tutor, and orange tree pruner. He also continued to pursue jobs as extras for major pictures, and even got some work as a prop buyer for an independent studio. Capra wrote short stories during this time, but was unable to get them published.

By this point, the future director was consumed with dreams of show business. In August of 1919, Capra, along with former actor W.M. Plank and financial backer Ida May Heitmann, incorporate the Tri-State Motion Picture Co. in Nevada. The outfit produced three short films in 1920, "Don't Change Your Husband," "The Pulse of Life," and "The Scar of Love," all directed by Plank. The films flopped and Capra moved back to L.A. when "Tri-State" broke up, earning a job at CBC Film Sales Co. where he worked as an editor and director on a series called "Screen Snapshots." The job was unsatisfying and five months later, in August of 1920 he moved to San Francisco where he worked as a door-to-door salesman and learned to ride the rails with a hobo named Frank Dwyer.

The next year, San Francisco-based producer Walter Montague hired Capra for $75/week to help direct the short film, "Fulta Fisher's Boarding House," which was based on a Rudyard Kipling poem. The film sold for a small profit, and Montague's vision of producing films based off of poems was fueled. Capra quit working for the producer, however, when he announced that the next film would be based off of one of his own poems.

His next gigs, in 1921, were as an assistant at Walter Ball's film lab and for the Paul Gerson Picture Corp. where he helped make their two-reel comedies as an editor. It was here that Frank began dating the actress Helen Edith Howe, eventually marrying her on November 25, 1923. The couple soon moved to Hollywood where producer Hal Roach hired Capra in January of 1924 as a gag-writer for the comedy series "Our Gang". However, after seven weeks and five episodes, Frank quit when Roach refused to make him the director. Capra then went to work for Mack Sennett as one of six writers for silent movie comedian Harry Langdon.

Langdon's popularity grew during this time and his production unit turned their focus to creating features for him to star in. Eventually, Langdon outgrew Sennet's team and left the group in September, 1925. Capra continued to work with Sennet for a short while, but was sacked and subsequently hired by Langdon as a gag writer, working on first on his succesful feature, "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp" (1924). For Langdon's next picture, "The Strong Man", Capra was promoted to director, earning a salary of $750/week.

Around this time, Frank's marriage to Helen began to come undone when it was discovered that she had a life-threatening ectopic pregnancy that had to be terminated. In order to cope with the tragedy Capra became a workaholic and Helen turned to alcohol. The deterioration of his marriage paralleled the demise of his relationship with Langdon during the making of "Long Pants" (1927), which would be Capra's last with the star. Langdon, usually clashing with Capra's optimistic nature and siding with screenwriter Arthur Ripley, decided to direct his own features. His next three films were disasters and Harry Langdon's career soon sank with the advent of sound technology in film.

In April of 1927, Frank and his wife separated, and Capra took the opportunity to move to New York in order to direct "For the Love of Mike" (1927) for the First National production company. The director and the film's star, Claudette Colbert did not get along, and to make matters worse production went over-budget resulting in First National's refusal to pay Capra.

Capra hitchhiked back to Hollywood and by September of 1927 he was working as a writer again for Mack Sennett briefly before receiving a directing job from Columbia Pictures President and Production Chief Harry Cohn. His first film there was "That Certain Thing", which Cohn was delighted with, doubling Capra's salary to $3,000 per picture. Capra's several next features were all succesful, including 1928's "Submarine". He then directed the high-budget "The Younger Generation" in 1929 which would be his first sound film. In the summer of that year, Capra was introduced to the widow, [[Lucille Warner Reyburn who would become his second wife.

That same year the director also met the transplanted stage actress Barbara Stanwyck and casted her for his next film "Ladies of Leisure" (1930). Stanwyck and Capra made a good team, and it was with her that he began to develop his mature directorial style. This was a result of Stanwyck's unpredictability as an actress, ususually deteriorating steadily after rehearsals or retakes. Knowing that her first scene was usually her best, Capra started blocking out scenes in advance, and preparing his other actors so that they could react to Stanwyck in the first shot so that they wouldn't disrupt continuity. In response to this semi-improvisatory style, the crew had to boost its level of craftmanship to beyond normal Hollywood productions, which were typically forged in more static and prosaic work conditions. Thus, the professionalism of Capra's crew became better than those of other outfits.

After "Ladies of Leisure" Capra was assigned to direct "Platinum Blond" (1931) starring Jean Harlow. Through the film's character, Stew Smith, came the debut of the prototypical "Capra" hero. Recognizing that he had something in his star director, Harry Cohn gradually took his lowly studio from out of Poverty Row by putting everything he had into Capra's control, including the left-over scripts and actors from some of the more major production companies, such as Warner Brothers and MGM.

Starting in 1932, with "American Madness", Capra shifted from his pattern of making flicks dealing with more "escapist" plot-lines, to creating motion pictures that were based more in reality, reflecting the social conditions of the day. It was also with "Madness" that Capra made a bold move against the cinematic "grammar" of his day, by fastening the pace of the plot by removing many of the actors entrances and exits in scenes, as well as by overlapping the actors' dialogue, eliminating the slow disolves in scene transitions, and other changes to shorten significantly the length of scenes. This created a sense of urgency which better held the attention of the audience. Except for on "mood pieces" Capra began to use this technique on all his future films and was heralded by directors for the "naturalness" of his directing.

By the release of his film, "Lady for a Day" (1933), Capra had established not only his technique as a director but his voice (themes and style) as one well. This style would later be dubbed by critics as "Capra-corn" for its sentimental, feel-good nature. "Lady for a Day" would be the first film of the young director's, as well as Columbia's, to attract the attention of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, earning him four nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Writing for an Adaptation (Robert Riskin), and a Best Actress nod to star May Robson.

Though the nominations were a welcome honor for the young director, the actual night of the awards ceremony (March 16, 1934) would go down as one of Capra's most humiliating experiences. Capra, with high hopes of winning an Oscar, had his mind set on nothing else. When host Will Rogers opened the envelope for Best Director, he commented, "Well, well, well. What do you know. I've watched this young man for a long time. Saw him come up from the bottom, and I mean the bottom. It couldn't have happened to a nicer guy. Come on up and get it, Frank!"

Capra sprang from his chair and squeezed past tables to make his way out to the open dance floor to accept his award. In his own words: "The spotlight searched around trying to find me. 'Over here!' I waved. Then it suddenly swept away from me - and picked up a flustered man standing on the other side of the dance floor - 'Frank Lloyd' !"

Capra's walk back to his table amidst shouts of "Sit down!" turned into the "...longest, saddest, most shattering walk in my life. I wished I could have crawled under the rug like a miserable worm. When I slumped in my chair I felt like one. All of my friends at the table were crying."

The following year would redeem Capra when he received the Best Director trophy for his romantic comedy "It Happened One Night" (1934). The following year, Capra further redeemed himself when he was asked to become president of the Academy, a position he would serve well, as many have given him the credit of saving the institution from its demise. This regards the mass boycott that actors, writers, and directors undertook of the Academy in 1933, as part of the newly formed unions that were the Screen Actors Guild, Screen Writer's Guild, and Screen Directors Guild. Capra was responsible for smoothing over the strife by making the call that the Academy should stay out of labor relations. His other significant modifications to the program were: democratizing the nomination process in order to eliminate studio politics, opening the cinematography and interior decoration awards to films made outside the U.S., and creating two new acting awards for supporting performances. By the 1937 awards ceremony, SAG announced that it had no objection to its members attending. To add icing to the cake, that night Capra won his second Oscar for directing "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town" (1936), which also won the Best Picture award.

In 1939, Capra was voted president of the SDG and began negotiating with AMPAS President Joseph Schneck for the industry to recognize the SDG as the sole collective bargaining agent for directors. Schneck refused and Capra threatened a strike and resignation from the Academy. Schneck gave in and one week later, at the Oscar awards ceremony, Capra won his third Best Director title for "You Can't Take it With You" (1938), which also took home Best Picture. In 1940, Capra's term as President of the Academy would end.

In this period, between 1934 to 1941, Capra created the core of his canon with the timeless hits, "It Happened One Night," "Mr Deeds Goes to Town" (1936), "You Can't Take it With You: (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and "Meet John Doe" (1941), winning three Best Director Oscars in the process. Some cine-historians call Capra the great American propagandist, as he had been so effective in creating an indelible impression of America in the 1930s. "Maybe there never was an America in the thirties," John Cassavetes was quoted as saying. "Maybe it was all Frank Capra."

When the United States went to war again in December of 1941, Frank Capra rejoined the Army as a legitimate propagandist, creating a highly popular series called, "Why We Fight." When the war ended, he founded Liberty Films with John Ford and ultimately made his last classic there, "It's a Wonderful Life" in 1946. After a dismal output over the following three years, Capra took an eight-year hiatus from feature films. During this time, the director created the memorable series of semi-comic science documentaries for television that became required viewing for school kids in the 1960's.

But it was Capra's great mastery over film that was the key to his success. Comparing Capra to Dickens in a not wholly flattering review of "You Can't Take it With You," Green found Capra "'a rather muddled and sentimental idealist who feels - vaguely - that something is wrong with the social system' (807). Commenting on the improbable scene in which Grandpa Vanderhof persuades the munitions magnate Anthony P. Kirby to give everything up and play the harmonica, Greene stated:

"It sounds awful, but it isn't as awful as all that, for Capra has a touch of genius with a camera: his screen always seems twice as big as other people's, and he cuts as brilliantly as Eisenstein (the climax when the big bad magnate takes up his harmonica is so exhilarating in its movement that you forget its absurdity). Humour and not wit is his line, a humour that shades off into whimsicality, and a kind of popular poetry which is apt to turn wistful. We may groan and blush as he cuts his way remorselessly through all finer values to the fallible human heart, but infallibly he makes his appeal - to that great soft organ with its unreliable goodness and easy melancholy and baseless optimism. The cinema, a popular craft, can hardly be expected to do more."

Capra was a populist, and the simplicity of his narrative structures, in which the great social problems facing America were boiled down to scenarios in which metaphorical boy scouts took on corrupt political bosses and evil-minded industrialists, created mythical America of simple archetypes that with its humor, created powerful films that appealed to the elemental emotions of the audience. The immigrant who had struggled and been humiliated but persevere due to his inner resolution harnessed the mytho-poetic power of the movie to create proletarian passion plays that appealed to the psyche of the New Deal movie-goer. The country during the Depression was down but not out, and the ultimate success of the individual in the Capra films was a bracing tonic for the movie audience of the 1930s. His own personal history, transformed on the screen, became their myths that got them through the Depression, and when that and the war was over, the great filmmaker found himself out of time. Capra, like Charles Dickens, moralized political and economic issues. Both were primarily masters of personal and moral expression, and not of the social and political. It was the emotional realism, not the social realism, of such films as "Mr Smith Goes To Washington" which he was concerned with, and by focusing on the emotional and moral issues his protagonists faced, typically dramatized as a conflict between cynicism and the protagonist's faith and idealism, that made the movies so powerful, and made them register so powerfully with an audience.

Born Francesco Rosario Capra in Bisacquino, Sicily, Capra moved to the United States in 1903 with his father Salvatore, his mother Rosaria Nicolosi, and his siblings Giuseppa, Giuseppe, and Antonia. In California they met up with Benedetto Capra, (the oldest sibling) and settled in Los Angeles where, in 1918, Frank Capra graduated from Throop Institute (later renamed the California Institute of Technology) with a B.S. degree in chemical engineering. On October 18, 1918, he joined the United States Army. While at the Presidio, he got Spanish influenza and was discharged on December 13. In 1920, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States, registering his name as Frank Russell Capra.

Film career

Like other prominent directors of the 1930s and '40s, Capra began his career in silent films, notably by directing and writing silent film comedies starring Harry Langdon and the Our Gang kids. In 1930 Capra went to work for Mack Sennett and then moved to Columbia Pictures where he formed a close association with screenwriter Robert Riskin (husband of Fay Wray) and cameraman Joseph Walker. In 1940, however, Sidney Buchman replaced Riskin as writer.

For the 1934 film It Happened One Night, Robert Montgomery and Myrna Loy were originally offered the roles, but each felt that the script was poor, and Loy described it is one of the worst she had ever read, later noting that the final version bore little resemblance to the script she and Montgomery were offered.[1]After Loy, Miriam Hopkins and Margaret Sullavan also each rejected the part.[2] Constance Bennett wanted to, but only if she could produce it herself. Then Bette Davis wanted the role,[3] but she was under contract with Warner Brothers and Jack Warner refused to loan her to Columbia Studios.[4] Capra was unable to get any of the actresses he wanted for the part of Ellie Andrews, partly because no self-respecting star would make a film with only two costumes.[5] Harry Cohn suggested Claudette Colbert to play the lead role. Both Capra and Clark Gable enjoyed making the movie. After the 1934 film It Happened One Night, Capra directed a steady stream of films for Columbia intended to be inspirational and humanitarian.

The best known are Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, the original Lost Horizon, You Can't Take It with You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It's a Wonderful Life. His ten-year break from screwball comedy ended with the comedy Arsenic and Old Lace. Among the actors who owed much of their early success to Capra were Gary Cooper, Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Barbara Stanwyck, Cary Grant and Donna Reed. Capra credited Jean Arthur as "my favorite actress."

Capra's films in the 1930s enjoyed success at the Academy Awards. It Happened One Night was the first film to win all five top Oscars, Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress and Best Screenplay. In 1936, Capra won his second Best Director Oscar for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and in 1938 he won his third Best Director Oscar in just five years for You Can't Take It with You which also won Best Picture. In addition to his three directing wins, Capra received directing nominations for three other films (Lady for a Day, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It's a Wonderful Life). He was also host of the 8th Academy Awards ceremony on 5 March 1936.

Although these films, written by individuals on the political left, tend to exude the spirit of the New Deal, Capra himself was a conservative Republican who hated President Franklin D. Roosevelt (never voting for him), admired Franco and Mussolini, and later during the McCarthy era served as a secret FBI informer.[6]

World War II

Between 1942 and 1948, when he produced State of the Union, Capra also directed or co-directed eight war documentaries including Prelude to War (1942), The Nazis Strike (1942), The Battle of Britain (1943), Divide and Conquer (1943), Know Your Enemy Japan (1945), Tunisian Victory (1945) and Two Down and One to Go (1945). His Academy Award-winning documentary series, Why We Fight, is widely considered a masterpiece of propaganda. Capra was faced with the task of convincing an isolationist nation to enter the war, desegregate the troops, and ally with the Russians, among other things. Capra would regard these films as his most important work, see them as his way to counter German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl's films, in particular Triumph of the Will. Prelude to War won the 1942 Academy Award for Documentary Feature.

Postwar

It's a Wonderful Life (1946) is perhaps Capra's most widely known and long-lasting film to date. Although it was initially considered a box office disappointment, it was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Sound Recording and Best Editing. The film gained a second life on television, where for a number of years it was shown multiple times during the Christmas season. A lapse in its copyright protection caused the film to appear to fall into the public domain, and TV stations believed they were allowed to show it without paying royalties. With the new exposure, It's a Wonderful Life became a Christmas classic.

Even though the copyright on the film itself lapsed, it was still protected by virtue of it being a derivative work of all the other copyrighted material used to produce the film such as the script, music, etc. whose copyrights were renewed. In 1993, Republic Pictures, which was the successor to NTA, relied on the 1990 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Stewart v. Abend (which involved the movie Rear Window) to enforce its claim of copyright; while the film's copyright had not been renewed, it was a derivative work of various works that were still copyrighted. As a result, the film is no longer shown as much on television (NBC is currently the only network licensed to show the film on U.S. network television).

The American Film Institute named it one of the best films ever made, putting it at the top of the list of AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers, a list of what AFI considers to be the most inspirational American movies of all time. The film also appeared in another AFI Top 100 list: it placed at 11th on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies list of the top American films.

Capra's final theatrical film was 1961's Pocketful of Miracles, with Glenn Ford and Bette Davis. He had planned to do a science fiction film later in the decade but never even got around to pre-production. Capra did end up producing several science-related television specials for the Bell Telephone System, such as "The Strange Case of the Cosmic Rays."

Capra films usually carry a definite message about the basic goodness of human nature and show the value of unselfishness and hard work. His wholesome, feel-good themes have led his works to be called 'Capra-corn'. However, many others who see the positive aspects of Capra's works prefer the term, "Capraesque." It may be argued that much of the 'feel-good' type of cinema that has somewhat become a genre of its own, for better or for worse, is largely Frank Capra's legacy.[citation needed]

At the Yale Law School Film Society weekend with Capra in 1972, Jean Arthur attended a small afternoon symposium at his invitation. Capra urged her to stay for the screening that night, and assured her the audience would be delighted and overwhelmingly enthusiastic. Arthur declined because, she said, she had to go home and feed her cats.

Capra in the media

In 1971, Capra published his autobiography, The Name Above the Title. Uncompromising in its details, it offers a compelling self-portrait. It is, however, not considered to be entirely reliable as regards dates and facts; one commentator asserts that it "appears to have been a lie practically from beginning to end".[7]

Capra was also the subject of a 1991 biography by Joseph McBride entitled Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. McBride challenges many of the impressions left by Capra's autobiography.

Death and legacy

Frank Capra died in La Quinta, California of a heart attack in his sleep in 1991 at the age of 94. He was interred in the Coachella Valley Cemetery in Coachella, California.

He left part of his 1,100-acre ranch in Fallbrook, California to Caltech.[8]

His son Frank Capra, Jr. — one of the three children born to Capra's second wife, Lou Capra — is president of Screen Gems, in Wilmington, North Carolina. Frank Capra's grandson is Frank Capra III.

Quotes

- "There are no rules in filmmaking, only sins. And the cardinal sin is dullness."[citation needed]

Filmography

|

|

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Kotsabilas-Davis, James and Loy, Myrna. Being and Becoming. New York: Primus, Donald I Fine Inc., 1987, p. 94. ISBN 1-55611-101-0.

- ↑ Wiley, Mason and Bona, Damien. Inside Oscar: The Unofficial History of the Academy Awards. New York: Ballantine Books, 1987, p. 54. ISBN 0-345-34453-7.

- ↑ It Happened One Night - Frank CapraErik Weems, UPDATED JUNE 22, 2006

- ↑ Chandler, Charlotte. The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis, A Personal Biography. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006, p. 102. ISBN 0-78628-639-3.

- ↑ moviediva ItHappenedOneNight

- ↑ Gewen.

- ↑ Gewen.

- ↑ The Caltech Y History

- Capra, Frank. Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1971. ISBN 0-30680-771-8.

- Gewen, Barry. "It Wasn't Such a Wonderful Life." The New York Times, May 3, 1992. It Wasn't Such a Wonderful Life Access date: May 2, 2007.

External links

- Frank Capra at the Internet Movie Database

- Frank Capra at the TCM Movie Database

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Frank Lloyd for Cavalcade |

Academy Award for Best Director for It Happened One Night 1934 |

Succeeded by: John Ford for The Informer |

| Preceded by: John Ford for The Informer |

Academy Award for Best Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town 1936 |

Succeeded by: Leo McCarey for The Awful Truth |

| Preceded by: Leo McCarey for The Awful Truth |

Academy Award for Best Director for You Can't Take It with You 1938 |

Succeeded by: Victor Fleming for Gone with the Wind |

| Preceded by: Billy Wilder for The Lost Weekend |

Golden Globe Award for Best Director - Motion Picture for It's a Wonderful Life 1947 |

Succeeded by: Elia Kazan for Gentleman's Agreement |

| Preceded by: Irvin S. Cobb 7th Academy Awards |

Oscars host 8th Academy Awards |

Succeeded by: George Jessel 9th Academy Awards |

| Films Directed by Frank Capra |

|---|

| The Strong Man • For the Love of Mike • Long Pants • The Power of the Press • Say It with Sables • So This Is Love • Submarine • The Way of the Strong • That Certain Thing • The Matinee Idol • Flight • The Donovan Affair • The Younger Generation • Rain or Shine • Ladies of Leisure • Dirigible • The Miracle Woman • Platinum Blonde • Forbidden • American Madness • The Bitter Tea of General Yen • Lady for a Day • It Happened One Night • Broadway Bill • Mr. Deeds Goes to Town • Lost Horizon • You Can't Take It with You • Mr. Smith Goes to Washington • Meet John Doe • Arsenic and Old Lace • It's a Wonderful Life • State of the Union • Riding High • Here Comes the Groom • A Hole in the Head • Pocketful of Miracles |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.