Difference between revisions of "Enki" - New World Encyclopedia

| (74 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}} |

| − | '''Enki''' was a major [[deity]] in [[Mesopotamian religion|Sumerian mythology]], later known as '''Ea''' in [[Babylonian mythology]]. He was originally the chief god of the city of [[Eridu]]. | + | [[Image:Copia de Enki.jpg|thumb|200px|Depiction of Enki from a cylinder seal at the British Museum]] |

| + | '''Enki''' was a major [[deity]] in [[Mesopotamian religion|Sumerian mythology]], later known as '''Ea''' in [[Babylonian mythology]]. He was originally the chief god of the city of [[Eridu]]. The exact meaning of Enki's name is uncertain. The common translation is "Lord of the Earth." | ||

| − | Enki was the god of [[ | + | Enki was the god of [[water]], [[craft]]s, [[intelligence]], and [[Creation theory|creation]]. He was generally beneficent toward humankind and is portrayed in several myths as risking the other gods' disapproval by showing compassion for those treated unfairly. In Babylonian mythology he was also the father of young storm deity [[Marduk]], who assumed the role of king of the gods in the second millennium B.C.E.. In later Mesopotamian religion, Enki/Ea became part of a primary triad of deities consisting of [[Anu]] (deep heaven), [[Enlil]] (sky and earth), and himself (waters). |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Some scholars believe that Ea, as well as his father Anu, may be associated to some degree with later western Semitic gods such as the [[Canaan]]ite [[El]] and the Hebrew [[Yahweh]]. The patriarch [[Abraham]] originally came from the area near the center of Enki's worship and may have derived some of his understanding of God from the qualities attributed to deities such as Enki, [[Anu]], and [[Enlil]]. | ||

| − | The | + | ==Origins and attributes== |

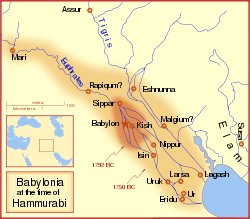

| + | [[Image:Hammurabi's Babylonia 1.svg|thumb|250px|Babylonia in the early second millennium B.C.E. The early worship of Enki was centered in Eridu, to the far south.]] | ||

| + | ''Enki'' is commonly translated is "Lord of the Earth." The Sumerian, ''en'' was a title equivalent to "lord." It was also the title given to the [[high priest]]. ''Ki'' means "earth," but there are theories that the word in this name has another origin. The later name '''Ea'' is either [[Hurrian]] or [[Semitic]] in origin.<ref>Herbert B. Huffmon, ''Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts: A Structural and Lexical Study'' (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965, ISBN 978-0801802836).</ref> In Sumerian, "E-A" means "the house of water," and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to Enki at [[Eridu]]. | ||

| + | {{readout||left|250px|The [[Sumerian]] [[deity]] "Enki" ("Lord of the Earth") was born when the tears of [[Anu]], the chief god, met the salt waters of the sea goddess [[Nammu]]}} | ||

| + | Enki was born, along with his sister [[Ereshkigal]], when [[Anu]]'s tears—shed for for his separated sister-lover [[Ki]] (earth)—met the salt waters of the primeval sea goddess [[Nammu]]. Enki was the keeper of the holy powers called ''[[Me (mythology)|Me]]'', the gifts of [[civilization|civilized]] living. The main temple of Enki was called ''é-engur-a'', the "house of the lord of deep waters." It was located in [[Eridu]], which was then in the wetlands of the [[Euphrates]] valley, not far from the [[Persian Gulf]]. | ||

| − | + | Enki was also the master shaper of the world and the god of [[wisdom]] and of all [[magic]]. It was he who devised a way to travel over water in a reed boat, in an attempt to rescue his sister Ereshkigal when she was abducted from heaven. | |

| − | + | In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty river beds and fills them with his "water."<ref>C.A. Benito, "Enki and Ninmah" and "Enki and the World Order," dissertation, University of Philadelphia, 1969.</ref> This may be a reference to Enki's fertile [[hieros gamos|sacred marriage]] with [[Ninhursag]] (the Earth goddess). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | Enki | + | Enki/Ea was sometimes depicted as a man covered with the skin of a [[fish]], and this representation points decidedly to his original character as a god of the waters. His temple was also associated with Ninhursag's shrine, which was called ''Esaggila'' (the lofty sacred house), a name shared with [[Marduk]]'s temple in Babylon, implying a staged tower or [[ziggurat]]. It is also known that incantations, involving ceremonial rites in which water as a sacred element played a prominent part, formed a feature of his worship. |

| − | Enki | + | Enki came to be the lord of the [[Apsu]] ("[[abyss]]"), the freshwater ocean of [[groundwater]] under the [[earth]]. In the later Babylonian myth ''[[Enuma Elish]]'' Apsu, and his salt-water consort [[Tiamat]] (possibly the Babylonian version of the Sumerian Nammu) "mingle their waters" to generate the other gods. Apsu finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods and sets out to destroy them. Enki here is Apsu's grandson, and is chosen by the younger gods to put a death-like spell on Apsu, "casting him into a deep sleep" and confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home "in the depths of the Apsu." Enki thus usurps Apsu's position and takes on his earlier functions, including his fertilizing powers.<ref>Gwendolyn Leick, ''Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City'' (Penguin, 2003, ISBN 978-0140265743).</ref> Enki is also the father of future king of the gods, [[Marduk]], the storm deity who conquers Tiamat and takes the tablets of destiny from her henchman [[Kingu]]. |

| − | Enki | + | Enki was considered a god of life and replenishment. He was often depicted with two streams of water emanating from his shoulders, one the [[Tigris]], the other the [[Euphrates]]. Alongside him were trees symbolizing the male and female aspects of nature, each holding the male and female aspects of the "Life Essence," which he, the alchemist of the gods, would masterfully mix to create several beings that would live upon the face of the earth. |

| − | + | The consort of Ea originally was fully equal with him, but in more [[patriarchy|patriarchal]] Assyrian and [[Neo-Babylonian]] times she plays a part merely in association with her lord. Generally, however, Enki seems to be a reflection of pre-patriarchal times, in which relations between the sexes were characterized by a situation of greater [[gender equality]]. In his character, he prefers persuasion to conflict, which he seeks to avoid if possible. He is, to put it in modern terms, a lover and a magician, not a fighter. | |

| − | + | Although he is clever, the character of Enki is not that of a simple [[trickster]] god. He is not beyond bending the divine rules, but he is not an outright [[cheat]]. Enki uses his magic for the good of others when called upon to help either a god, a goddess, or a human. He remains true to his own essence as a [[masculinity|masculine]] nurturer. He is a problem-solver who disarms those who bring conflict and death to the world. He is the mediator whose [[compassion]] and sense of humor breaks and disarms the wrath of his stern half-brother, [[Enlil]]. | |

| − | Enki's symbols included a [[goat]] and a [[fish]] | + | Enki's symbols included a [[goat]] and a [[fish]]. These later combined into a single beast, the goat [[Capricorn]], which became one of the signs of the [[zodiac]]. In Sumerian astronomy he represented the planet [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]], known for its ability to shift rapidly, and its proximity to the [[Sun]]. |

| − | ==Life-giving but lustful== | + | ==Mythology== |

| − | As the god of water Enki had a penchant for [[beer]], and | + | ===Life-giving but lustful=== |

| + | As the god of water, Enki had a penchant for [[beer]], and with his fertilizing powers he had a string of [[incest]]uous affairs. In the epic ''Enki and Ninhursag'', he and his consort [[Ninhursag]] had a daughter named [[Ninsar]] (Lady Greenery). When Ninhursag left him, he had intercourse with Ninsar, who gave birth to [[Ninkurra]] (Lady Pasture). He later had intercourse with Ninkurra, who gave birth to [[Uttu]] (Weaver or Spider). Enki then attempted to seduce Uttu. She consulted Ninhursag, who, upset at the promiscuous nature of her spouse, advised her to avoid the riverbanks and thus escape his advances. | ||

| − | In another version of this story, the seduction succeeds. Ninhursag takes Enki's | + | In another version of this story, the seduction succeeds. Ninhursag then takes Enki's seed from Uttu's womb and plants it in the earth, where seven plants rapidly germinate. Enki finds the plants and immediately starts consuming their fruit. Thus, consuming his own fertile essence, he becomes pregnant, falling ill with swellings in his jaw, his teeth, his mouth, his throat, his limbs, and his ribs. The gods are at a loss as to what to do, since Enki lacks a womb with which to give birth. Ninhursag now relents and takes Enki's "water" into her own body. She gives birth to the gods of healing of each part of the body. The last one is [[Ninti]], (Sumerian = Lady Rib). Ninti is given the title of the "mother of all living." This was also a title given to the later [[Hurrian]] [[goddess]] [[Hebat|Kheba]] and to the biblical [[Eve (Bible)|Eve]], who was supposedly made from the rib of [[Adam]]. |

===Confuser of languages=== | ===Confuser of languages=== | ||

| − | In the Sumerian epic ''[[Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta]]'', an incantation is pronounced with a mythical introduction indicating | + | In the Sumerian epic ''[[Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta]]'', an incantation is pronounced with a mythical introduction indicating that Enki was the source of the world's multiplicity of languages:<ref>[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1823.htm This translation] describes 'Hamazi, the many-tongued' and instead calls on Enki to change the languages of mankind into one. Retrieved August 24, 2019.</ref> |

:Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion, | :Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion, | ||

| − | :There was no hyena, there was no lion, | + | :There was no hyena, there was no lion, there was no wild dog, no wolf, |

| − | + | :There was no fear, no terror. Man had no rival... | |

| − | :There was no fear, no terror | ||

| − | |||

| − | :The whole universe, the people in unison | + | :The whole universe, the people in unison to Enlil in one tongue [spoke]. |

| − | |||

:(Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy, | :(Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy, | ||

| − | :The lord of wisdom, who understands the land, | + | :The lord of wisdom, who understands the land, the leader of the gods, endowed with wisdom, |

| − | + | :The lord of [[Eridu]] changed the speech in their mouths, [brought] contention into it, | |

| − | :The lord of [[Eridu]] changed the speech in their mouths, | ||

:Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one. | :Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one. | ||

===Savior of humankind=== | ===Savior of humankind=== | ||

| − | Yet Enki risked the anger of Enlil and the other gods in order to save humanity from the Deluge designed by the gods to kill them. In the Legend of [[Atrahasis]] | + | [[Image:GilgameshTablet.jpg|thumb|In the Deluge tablet of the [[Epic of Gilgamesh]], Enki is the god who informs [[Utnapishtim]] of the coming flood.]] |

| + | Yet Enki risked the anger of [[Enlil]] and the other gods in order to save humanity from the [[Deluge]] designed by the gods to kill them. In the Legend of [[Atrahasis]]—later adapted into a section of the [[Epic of Gilgamesh]]—Enlil sets out to eliminate humanity, whose overpopulation and resultant mating noise is offensive to his ears. He successively sends drought, famine, and plague to do away with humankind. However, Enki thwarts his half-brother's plans by teaching Atrahasis the secrets of irrigation, granaries, and medicine. The enraged Enlil, convenes a council of the gods and convinces them to promise not to tell [[Humanity (abstraction)|humankind]] that he plans their total annihilation. Enki does not tell Atrahasis directly, but speaks of Enlil's plan to the walls of Atrahasis' reed hut, which, of course, the man overhears. He thus covertly rescues Atrahasis ([[Utnapishtim]] in the Epic of Gilgamesh) by either instructing him to build a boat for his family and animals, or by bringing him into the heavens in a magic ship. | ||

| − | + | Enlil is angry that his will has been thwarted yet again, and Enki is named as the culprit. Enki argues that Enlil is unfair to punish the guiltless Atrahasis for the sins of his fellows and secures a promise that the gods will not eliminate humankind if they practice birth control and live in harmony with the natural world. | |

===Enki and Inanna=== | ===Enki and Inanna=== | ||

| − | In his connections with [[Inanna]] ([[Ishtar]]) Enki, | + | In his connections with [[Inanna]] ([[Ishtar]]) Enki, demonstrates other aspects of his non-[[Patriarchy|patriarchal]] attitude. In the myth of ''Inanna's descent'', Enki again shows his compassion where the other gods do not.<ref>Diana Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, ''Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth'' (Harper Perennial, 1983, ISBN 978-0060908546).</ref> Inanna sets out on a journey to the underworld in order to console her grieving sister [[Ereshkigal]], who is mourning the death of her husband [[Gugalana]] (Gu=Bull, Gal=Great, Ana=Heaven), slain by the heroes [[Gilgamesh]] and [[Enkidu]]. In case she does not return in three days, she tells her servant Ninshubur (Nin=Lady, Shubur=Evening} to get help either from her father [[Anu]], [[Enlil]], or Enki. When she does not return, Ninshubur approaches Anu only to be told that he understands that his daughter is strong and can take care of herself. Enlil tells Ninshubur he is much too busy running the cosmos. However, Enki immediately expresses concern and dispatches his demons, Galaturra or Kurgarra to recover the young goddess. |

| − | + | The myth ''Enki and Inanna''<ref>[http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/gods/ladies/ladyinanna1.html "Inanna: Lady of Love and War, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Morning and Evening Star"] ''gatewaystobabylon.com'', November 30, 2000. Retrieved August 24, 2019.</ref> tells the story of Inanna's journey from her city of [[Uruk]] to visit Enki at Eridu, where she is entertained by him in a feast. Enki plies her with beer and attempts to seduce her, but the young goddess maintains her virtue, while Enki proceeds to get drunk. In generosity he gives her all the gifts of his ''[[Me (Sumerian mythology)|Me]]''. Next morning, with a hangover, he asks his servant [[Isimud]] for his ''Me'', only to be informed that he has given them to Inanna. Enki sends his demons to recover his gifts. Inanna, however, escapes her pursuers and arrives safely back at Uruk. Enki realizes that he has been outwitted and accepts a permanent peace treaty with Uruk. | |

| − | In the story ''Inanna and Shukaletuda'',<ref>Lishtar "The Avenging Maiden and the Predator Gardener: a study of Inanna and Shukaletuda" | + | In the story ''Inanna and Shukaletuda'',<ref>Lishtar, [http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/essays/shukaletuda.html "The Avenging Maiden and the Predator Gardener: a study of Inanna and Shukaletuda"] ''www.gatewaystobabylon.com''. Retrieved August 24, 2019.</ref> Shukaletuda, the gardener, sent by Enki to care for the date palm he had created, finds Inanna sleeping under the palm tree and rapes her in her sleep. Awaking, she discovers that she has been violated and seeks to punish the miscreant. Shukaletuda seeks protection from Enki. He advises Shukaletuda to hide in the city, where Inanna will not be able to find him. Eventually, after cooling her anger, Inanna too seeks the help of Enki, as spokesperson of the assembly of the gods. After she presents her case, Enki sees that justice needs to be done and promises help, delivering to her the knowledge of where the Shukaletuda is hiding so she can take her revenge. |

==Influence== | ==Influence== | ||

| − | + | The incantations originally composed for the Ea cult were later edited by the priests of [[Babylon]] and adapted to the worship of [[Marduk]], who was Ea's son and became the king of the gods. Similarly, the hymns to Marduk betray traces of the transfer to Marduk of attributes which originally belonged to Ea. As the third figure in the heavenly triad—the two other members being [[Anu]] and [[Enlil]])—Ea acquired his later place in the pantheon. To him was assigned the control of the watery element, and in this capacity he becomes the'' '[[bêlu|shar]] apsi','' i.e. king of the Apsu or "the deep." The cult of Ea extended throughout Babylonia and [[Assyria]]. We find temples and shrines erected in his honor at Nippur, Girsu, [[Ur]], Babylon, Sippar and [[Nineveh]]. The numerous epithets given to him bear witness to the popularity which he enjoyed from the earliest to the latest period of Babylonian-Assyrian history. The inscriptions of Babylonian ruler [[Urukagina]] suggest that the divine pair Enki and his consort Ninki were the progenitors of seven pairs of gods, including Marduk, who later became the king of the gods. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

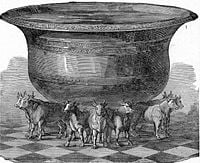

| − | + | [[Image:Brazen-sea.jpg|thumb|200px|The huge bronze "Sea" which sat at the entrance of the [[Temple of Jerusalem]] may have had its origins in the tradition of the "Apsu" associated with the worship of Enki.]] | |

| − | + | The pool of the freshwater [[Apsu]] at the front of Enki's temple was adopted also at the temple of the Moon ([[Nanna]]) at Ur, and spread throughout the Middle East. This tradition may have been carried over into Israelite tradition in the form of the bronze "Sea" which stood before [[Solomon's Temple]]. Some believe it still remains as the sacred pool at [[Mosques]], and as the [[Baptismal font]] in [[Christian]] [[Church]]es. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Myths in which Ea figures prominently have been found in [[Assurbanipal]]'s library and in the [[Hattusas]] [[archive]] in [[Hittites|Hittite]] [[Anatolia]]. As Ea, the deity had a wide influence outside of Sumeria, being associated in the [[Canaanite mythology|Canaanite]] [[Pantheon (gods)|pantheon]] with [[El (god)|El]] (at [[Ugarit]]) and possibly [[Yah]] (at [[Ebla]]). He is also found in [[Hurrian]] and Hittite mythology, as a god of contracts, and is particularly favorable to humankind. Among the Western Semites it is thought that Ea was equated to the term ''*hyy'' (Life)<ref>Peeter Espak, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28581203_Ancient_Near_Eastern_Gods_Enki_and_Ea_Diachronical_Analysis_of_Texts_and_Images_from_the_Earliest_Sources_to_the_Neo-Sumerian_Period Ancient Near Eastern Gods Enki and EA] ''ResearchGate'', 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2019.</ref>, referring to Enki's waters as life giving. | |

| − | + | In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of [[Paolo Matthiae]] of the [[University of Rome La Sapienza]] performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium B.C.E. city of [[Ebla]]. Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of [[El (god)|El]], king of the gods of the [[Canaan]]ite [[Pantheon (gods)|pantheon]], with "Ia." Jean Bottero and others have suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea. Moreover, Enki's [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] name "Ia" (two syllables) is declined with the Semitic ending as Iahu and may have developed into the later form of [[Yahweh]].<ref>Jean Bottero, ''Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia'' (University Of Chicago Press, 2004, ISBN 0226067181).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Benito, C.A. "Enki and Ninmah" and "Enki and the World Order," dissertation, University of Philadelphia, 1969. |

| − | * Bottero, Jean | + | * Bottero, Jean. ''Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia''. University Of Chicago Press, 2004. ISBN 0226067181 |

| − | * Kramer, Samuel Noah | + | * Dalley, Stephanie. ''Myths of Mesopotamia''. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0199538362 |

| − | * Kramer, S.N. and | + | * Huffmon, Herbert B. ''Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts: A Structural and Lexical Study''. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965. ISBN 978-0801802836 |

| − | * | + | * Jacobsen, Thorkild. ''Treasures of Darkness; A History of Mesopotamian Religion''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN 0300022913 |

| − | * | + | * Kramer, Samuel Noah. ''Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.E.'' University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998. ISBN 0812210476 |

| + | * Kramer, S.N. and J.R. Maier. ''Myths of Enki, the Crafty God''. Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0195055023 | ||

| + | * Leick, Gwendolyn. ''Mesopotamia: the invention of the city''. Penguin, 2003. ISBN 978-0140265743 | ||

| + | * Wolkstein, Diana and Samuel Noah Kramer. ''Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth''. Harper Perennial, 1983. ISBN 978-0060908546 | ||

| − | + | {{1911}} | |

| − | |||

[[Category:religion]] | [[Category:religion]] | ||

| + | [[category:biography]] | ||

{{Credit|205503756}} | {{Credit|205503756}} | ||

Latest revision as of 08:34, 5 February 2022

Enki was a major deity in Sumerian mythology, later known as Ea in Babylonian mythology. He was originally the chief god of the city of Eridu. The exact meaning of Enki's name is uncertain. The common translation is "Lord of the Earth."

Enki was the god of water, crafts, intelligence, and creation. He was generally beneficent toward humankind and is portrayed in several myths as risking the other gods' disapproval by showing compassion for those treated unfairly. In Babylonian mythology he was also the father of young storm deity Marduk, who assumed the role of king of the gods in the second millennium B.C.E. In later Mesopotamian religion, Enki/Ea became part of a primary triad of deities consisting of Anu (deep heaven), Enlil (sky and earth), and himself (waters).

Some scholars believe that Ea, as well as his father Anu, may be associated to some degree with later western Semitic gods such as the Canaanite El and the Hebrew Yahweh. The patriarch Abraham originally came from the area near the center of Enki's worship and may have derived some of his understanding of God from the qualities attributed to deities such as Enki, Anu, and Enlil.

Origins and attributes

Enki is commonly translated is "Lord of the Earth." The Sumerian, en was a title equivalent to "lord." It was also the title given to the high priest. Ki means "earth," but there are theories that the word in this name has another origin. The later name 'Ea is either Hurrian or Semitic in origin.[1] In Sumerian, "E-A" means "the house of water," and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to Enki at Eridu.

Enki was born, along with his sister Ereshkigal, when Anu's tears—shed for for his separated sister-lover Ki (earth)—met the salt waters of the primeval sea goddess Nammu. Enki was the keeper of the holy powers called Me, the gifts of civilized living. The main temple of Enki was called é-engur-a, the "house of the lord of deep waters." It was located in Eridu, which was then in the wetlands of the Euphrates valley, not far from the Persian Gulf.

Enki was also the master shaper of the world and the god of wisdom and of all magic. It was he who devised a way to travel over water in a reed boat, in an attempt to rescue his sister Ereshkigal when she was abducted from heaven.

In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty river beds and fills them with his "water."[2] This may be a reference to Enki's fertile sacred marriage with Ninhursag (the Earth goddess).

Enki/Ea was sometimes depicted as a man covered with the skin of a fish, and this representation points decidedly to his original character as a god of the waters. His temple was also associated with Ninhursag's shrine, which was called Esaggila (the lofty sacred house), a name shared with Marduk's temple in Babylon, implying a staged tower or ziggurat. It is also known that incantations, involving ceremonial rites in which water as a sacred element played a prominent part, formed a feature of his worship.

Enki came to be the lord of the Apsu ("abyss"), the freshwater ocean of groundwater under the earth. In the later Babylonian myth Enuma Elish Apsu, and his salt-water consort Tiamat (possibly the Babylonian version of the Sumerian Nammu) "mingle their waters" to generate the other gods. Apsu finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods and sets out to destroy them. Enki here is Apsu's grandson, and is chosen by the younger gods to put a death-like spell on Apsu, "casting him into a deep sleep" and confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home "in the depths of the Apsu." Enki thus usurps Apsu's position and takes on his earlier functions, including his fertilizing powers.[3] Enki is also the father of future king of the gods, Marduk, the storm deity who conquers Tiamat and takes the tablets of destiny from her henchman Kingu.

Enki was considered a god of life and replenishment. He was often depicted with two streams of water emanating from his shoulders, one the Tigris, the other the Euphrates. Alongside him were trees symbolizing the male and female aspects of nature, each holding the male and female aspects of the "Life Essence," which he, the alchemist of the gods, would masterfully mix to create several beings that would live upon the face of the earth.

The consort of Ea originally was fully equal with him, but in more patriarchal Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times she plays a part merely in association with her lord. Generally, however, Enki seems to be a reflection of pre-patriarchal times, in which relations between the sexes were characterized by a situation of greater gender equality. In his character, he prefers persuasion to conflict, which he seeks to avoid if possible. He is, to put it in modern terms, a lover and a magician, not a fighter.

Although he is clever, the character of Enki is not that of a simple trickster god. He is not beyond bending the divine rules, but he is not an outright cheat. Enki uses his magic for the good of others when called upon to help either a god, a goddess, or a human. He remains true to his own essence as a masculine nurturer. He is a problem-solver who disarms those who bring conflict and death to the world. He is the mediator whose compassion and sense of humor breaks and disarms the wrath of his stern half-brother, Enlil.

Enki's symbols included a goat and a fish. These later combined into a single beast, the goat Capricorn, which became one of the signs of the zodiac. In Sumerian astronomy he represented the planet Mercury, known for its ability to shift rapidly, and its proximity to the Sun.

Mythology

Life-giving but lustful

As the god of water, Enki had a penchant for beer, and with his fertilizing powers he had a string of incestuous affairs. In the epic Enki and Ninhursag, he and his consort Ninhursag had a daughter named Ninsar (Lady Greenery). When Ninhursag left him, he had intercourse with Ninsar, who gave birth to Ninkurra (Lady Pasture). He later had intercourse with Ninkurra, who gave birth to Uttu (Weaver or Spider). Enki then attempted to seduce Uttu. She consulted Ninhursag, who, upset at the promiscuous nature of her spouse, advised her to avoid the riverbanks and thus escape his advances.

In another version of this story, the seduction succeeds. Ninhursag then takes Enki's seed from Uttu's womb and plants it in the earth, where seven plants rapidly germinate. Enki finds the plants and immediately starts consuming their fruit. Thus, consuming his own fertile essence, he becomes pregnant, falling ill with swellings in his jaw, his teeth, his mouth, his throat, his limbs, and his ribs. The gods are at a loss as to what to do, since Enki lacks a womb with which to give birth. Ninhursag now relents and takes Enki's "water" into her own body. She gives birth to the gods of healing of each part of the body. The last one is Ninti, (Sumerian = Lady Rib). Ninti is given the title of the "mother of all living." This was also a title given to the later Hurrian goddess Kheba and to the biblical Eve, who was supposedly made from the rib of Adam.

Confuser of languages

In the Sumerian epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, an incantation is pronounced with a mythical introduction indicating that Enki was the source of the world's multiplicity of languages:[4]

- Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion,

- There was no hyena, there was no lion, there was no wild dog, no wolf,

- There was no fear, no terror. Man had no rival...

- The whole universe, the people in unison to Enlil in one tongue [spoke].

- (Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy,

- The lord of wisdom, who understands the land, the leader of the gods, endowed with wisdom,

- The lord of Eridu changed the speech in their mouths, [brought] contention into it,

- Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one.

Savior of humankind

Yet Enki risked the anger of Enlil and the other gods in order to save humanity from the Deluge designed by the gods to kill them. In the Legend of Atrahasis—later adapted into a section of the Epic of Gilgamesh—Enlil sets out to eliminate humanity, whose overpopulation and resultant mating noise is offensive to his ears. He successively sends drought, famine, and plague to do away with humankind. However, Enki thwarts his half-brother's plans by teaching Atrahasis the secrets of irrigation, granaries, and medicine. The enraged Enlil, convenes a council of the gods and convinces them to promise not to tell humankind that he plans their total annihilation. Enki does not tell Atrahasis directly, but speaks of Enlil's plan to the walls of Atrahasis' reed hut, which, of course, the man overhears. He thus covertly rescues Atrahasis (Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh) by either instructing him to build a boat for his family and animals, or by bringing him into the heavens in a magic ship.

Enlil is angry that his will has been thwarted yet again, and Enki is named as the culprit. Enki argues that Enlil is unfair to punish the guiltless Atrahasis for the sins of his fellows and secures a promise that the gods will not eliminate humankind if they practice birth control and live in harmony with the natural world.

Enki and Inanna

In his connections with Inanna (Ishtar) Enki, demonstrates other aspects of his non-patriarchal attitude. In the myth of Inanna's descent, Enki again shows his compassion where the other gods do not.[5] Inanna sets out on a journey to the underworld in order to console her grieving sister Ereshkigal, who is mourning the death of her husband Gugalana (Gu=Bull, Gal=Great, Ana=Heaven), slain by the heroes Gilgamesh and Enkidu. In case she does not return in three days, she tells her servant Ninshubur (Nin=Lady, Shubur=Evening} to get help either from her father Anu, Enlil, or Enki. When she does not return, Ninshubur approaches Anu only to be told that he understands that his daughter is strong and can take care of herself. Enlil tells Ninshubur he is much too busy running the cosmos. However, Enki immediately expresses concern and dispatches his demons, Galaturra or Kurgarra to recover the young goddess.

The myth Enki and Inanna[6] tells the story of Inanna's journey from her city of Uruk to visit Enki at Eridu, where she is entertained by him in a feast. Enki plies her with beer and attempts to seduce her, but the young goddess maintains her virtue, while Enki proceeds to get drunk. In generosity he gives her all the gifts of his Me. Next morning, with a hangover, he asks his servant Isimud for his Me, only to be informed that he has given them to Inanna. Enki sends his demons to recover his gifts. Inanna, however, escapes her pursuers and arrives safely back at Uruk. Enki realizes that he has been outwitted and accepts a permanent peace treaty with Uruk.

In the story Inanna and Shukaletuda,[7] Shukaletuda, the gardener, sent by Enki to care for the date palm he had created, finds Inanna sleeping under the palm tree and rapes her in her sleep. Awaking, she discovers that she has been violated and seeks to punish the miscreant. Shukaletuda seeks protection from Enki. He advises Shukaletuda to hide in the city, where Inanna will not be able to find him. Eventually, after cooling her anger, Inanna too seeks the help of Enki, as spokesperson of the assembly of the gods. After she presents her case, Enki sees that justice needs to be done and promises help, delivering to her the knowledge of where the Shukaletuda is hiding so she can take her revenge.

Influence

The incantations originally composed for the Ea cult were later edited by the priests of Babylon and adapted to the worship of Marduk, who was Ea's son and became the king of the gods. Similarly, the hymns to Marduk betray traces of the transfer to Marduk of attributes which originally belonged to Ea. As the third figure in the heavenly triad—the two other members being Anu and Enlil)—Ea acquired his later place in the pantheon. To him was assigned the control of the watery element, and in this capacity he becomes the 'shar apsi', i.e. king of the Apsu or "the deep." The cult of Ea extended throughout Babylonia and Assyria. We find temples and shrines erected in his honor at Nippur, Girsu, Ur, Babylon, Sippar and Nineveh. The numerous epithets given to him bear witness to the popularity which he enjoyed from the earliest to the latest period of Babylonian-Assyrian history. The inscriptions of Babylonian ruler Urukagina suggest that the divine pair Enki and his consort Ninki were the progenitors of seven pairs of gods, including Marduk, who later became the king of the gods.

The pool of the freshwater Apsu at the front of Enki's temple was adopted also at the temple of the Moon (Nanna) at Ur, and spread throughout the Middle East. This tradition may have been carried over into Israelite tradition in the form of the bronze "Sea" which stood before Solomon's Temple. Some believe it still remains as the sacred pool at Mosques, and as the Baptismal font in Christian Churches.

Myths in which Ea figures prominently have been found in Assurbanipal's library and in the Hattusas archive in Hittite Anatolia. As Ea, the deity had a wide influence outside of Sumeria, being associated in the Canaanite pantheon with El (at Ugarit) and possibly Yah (at Ebla). He is also found in Hurrian and Hittite mythology, as a god of contracts, and is particularly favorable to humankind. Among the Western Semites it is thought that Ea was equated to the term *hyy (Life)[8], referring to Enki's waters as life giving.

In 1964, a team of Italian archaeologists under the direction of Paolo Matthiae of the University of Rome La Sapienza performed a series of excavations of material from the third-millennium B.C.E. city of Ebla. Among other conclusions, he found a tendency among the inhabitants of Ebla to replace the name of El, king of the gods of the Canaanite pantheon, with "Ia." Jean Bottero and others have suggested that Ia in this case is a West Semitic (Canaanite) way of saying Ea. Moreover, Enki's Akkadian name "Ia" (two syllables) is declined with the Semitic ending as Iahu and may have developed into the later form of Yahweh.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Herbert B. Huffmon, Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts: A Structural and Lexical Study (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965, ISBN 978-0801802836).

- ↑ C.A. Benito, "Enki and Ninmah" and "Enki and the World Order," dissertation, University of Philadelphia, 1969.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City (Penguin, 2003, ISBN 978-0140265743).

- ↑ This translation describes 'Hamazi, the many-tongued' and instead calls on Enki to change the languages of mankind into one. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Diana Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth (Harper Perennial, 1983, ISBN 978-0060908546).

- ↑ "Inanna: Lady of Love and War, Queen of Heaven and Earth, Morning and Evening Star" gatewaystobabylon.com, November 30, 2000. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Lishtar, "The Avenging Maiden and the Predator Gardener: a study of Inanna and Shukaletuda" www.gatewaystobabylon.com. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Peeter Espak, Ancient Near Eastern Gods Enki and EA ResearchGate, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ↑ Jean Bottero, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia (University Of Chicago Press, 2004, ISBN 0226067181).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benito, C.A. "Enki and Ninmah" and "Enki and the World Order," dissertation, University of Philadelphia, 1969.

- Bottero, Jean. Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University Of Chicago Press, 2004. ISBN 0226067181

- Dalley, Stephanie. Myths of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0199538362

- Huffmon, Herbert B. Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts: A Structural and Lexical Study. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1965. ISBN 978-0801802836

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. Treasures of Darkness; A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1976. ISBN 0300022913

- Kramer, Samuel Noah. Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.E. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998. ISBN 0812210476

- Kramer, S.N. and J.R. Maier. Myths of Enki, the Crafty God. Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0195055023

- Leick, Gwendolyn. Mesopotamia: the invention of the city. Penguin, 2003. ISBN 978-0140265743

- Wolkstein, Diana and Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth. Harper Perennial, 1983. ISBN 978-0060908546

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.