Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Emily Hobhouse" - New World

m |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

[[Image:Hobhouse.jpg|right|frame|Emily Hobhouse.]] | [[Image:Hobhouse.jpg|right|frame|Emily Hobhouse.]] | ||

| − | '''Emily Hobhouse''' (April 9, 1860 — June 8, 1926) was a British welfare campaigner, who is primarily remembered for | + | '''Emily Hobhouse''' (April 9, 1860 — June 8, 1926) was a [[Great Britain|British]] welfare campaigner, who is primarily remembered for her work related to British [[concentration camp]s in [[South Africa]]. Despite criticism and hostility from the British government and [[mass media|media]], she succeeded in bringing to the attention of the British public the appalling conditions inside the camps for [[Boer]] women and children during the [[Second Boer War]], and bringing about positive change. Hobhouse became an honorary citizen of South Africa for her humanitarian work. |

| − | == | + | ==Life=== |

| + | '''Emily Hobhouse''' was born on April 9, 186 in Liskeard, Cornwall, in [[Great Britain]]. She was the daughter of an [[Anglican]] [[rector]], and sister of [[Leonard Hobhouse]]. Her mother died when she was 20, and she spent the next fourteen years looking after her father who was in poor health. | ||

| − | + | When her father died in 1895 she went to [[Minnesota]], [[United States]] to perform welfare work amongst Cornish [[mining|mineworkers]] living there, a trip organized by the wife of the [[Archbishop of Canterbury]]. There she became engaged to John Carr Jackson and the couple bought a ranch in [[Mexico]]. However, this did not prosper and the engagement was broken off. She returned to [[England]] in 1898 after losing most of her money in a speculative venture. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1899, at the outbreak of the [[Second Boer War]], she became involved with the South African Conciliation Committee. It was there that she heard of the high mortality rate in the [[Boer]] [[concentration camp]]s. Visiting them, she saw first hand the horrors. She publicized the problems and demanded reform. Her report, which remains a classic in its moving descriptions of the suffering of women and children, brought about change, but too late for too many victims. | |

| + | |||

| + | Hobhouse was an avid opponent of the [[World War I]] and protested vigorously against it. Through her offices, thousands of women and children were fed daily for more than a year in central [[Europe]] after this war. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hobhouse died in [[London]] in 1926 and her ashes were ensconced in a niche in the [[National Women's Monument]] at Bloemfontein, [[South Africa]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Work== | ||

When the [[Second Boer War]] broke out in October 1899, a [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] MP, Leonard Courtney, invited Hobhouse to become secretary of the women's branch of the South African Conciliation Committee, of which he was president. Upon taking up her position, Hobhouse wrote: | When the [[Second Boer War]] broke out in October 1899, a [[Liberal Party (UK)|Liberal]] MP, Leonard Courtney, invited Hobhouse to become secretary of the women's branch of the South African Conciliation Committee, of which he was president. Upon taking up her position, Hobhouse wrote: | ||

<blockquote>It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learned of the hundreds of [[Boer]] women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations… the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance.<ref>[http://www.anglo-boer.co.za/emily.html Emily Hobhouse] Retrieved June 25, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learned of the hundreds of [[Boer]] women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations… the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance.<ref>[http://www.anglo-boer.co.za/emily.html Emily Hobhouse] Retrieved June 25, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 29: | ||

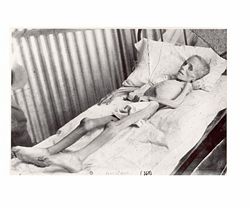

[[Image:LizzieVanZyl.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Lizzie van Zyl, visited by Emily Hobhouse in the Bloemfontein [[concentration camp]]]] | [[Image:LizzieVanZyl.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Lizzie van Zyl, visited by Emily Hobhouse in the Bloemfontein [[concentration camp]]]] | ||

| − | |||

Hobhouse had persuaded the authorities to let her visit several camps and to deliver aid – her report on conditions at the camps, set out in her report to the Committee of the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children, entitled ''Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies'' was delivered to the British government in June 1901. | Hobhouse had persuaded the authorities to let her visit several camps and to deliver aid – her report on conditions at the camps, set out in her report to the Committee of the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children, entitled ''Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies'' was delivered to the British government in June 1901. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 44: | ||

Hobhouse also visited camps at [[Norvalspont]], [[Aliwal North]], [[Springfontein]], [[Kimberley, Northern Cape|Kimberley]], and [[Orange River]]. | Hobhouse also visited camps at [[Norvalspont]], [[Aliwal North]], [[Springfontein]], [[Kimberley, Northern Cape|Kimberley]], and [[Orange River]]. | ||

| − | |||

When Hobhouse returned to [[England]], she received scathing criticism and hostility from the British government and the [[mass media|media]], but eventually succeeded in obtaining more funding to help the victims of the [[war]]. She also managed to successfully [[lobbying|lobby]] the government for an investigation of the conditions in the camps. The British [[Liberal]] leader at the time, Sir [[Henry Campbell-Bannerman]], denounced what he called the "methods of barbarism." The British government eventually agreed to set up the Fawcett Commission to investigate her claims, under [[Millicent Fawcett]], which corroborated her account of the shocking conditions. | When Hobhouse returned to [[England]], she received scathing criticism and hostility from the British government and the [[mass media|media]], but eventually succeeded in obtaining more funding to help the victims of the [[war]]. She also managed to successfully [[lobbying|lobby]] the government for an investigation of the conditions in the camps. The British [[Liberal]] leader at the time, Sir [[Henry Campbell-Bannerman]], denounced what he called the "methods of barbarism." The British government eventually agreed to set up the Fawcett Commission to investigate her claims, under [[Millicent Fawcett]], which corroborated her account of the shocking conditions. | ||

| − | Hobhouse returned to [[Cape Town]] in October 1901, but was not permitted to land and was eventually [[deportation|deported]] five days after arriving, no reason being given. Hobhouse then went to [[France]] where she wrote the book ''The Brunt of the War and | + | Hobhouse returned to [[Cape Town]] in October 1901, but was not permitted to land and was eventually [[deportation|deported]] five days after arriving, no reason being given. Hobhouse then went to [[France]] where she wrote the book ''The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell'' on what she saw during the war. |

| − | |||

After Hobhouse had met the [[Boer]] generals she learned from them that the distress of the women and children in the [[concentration camp]]s had contributed to their final resolution to surrender to [[Britain]]. She saw it then as her mission to assist in healing the wounds inflicted by the war and to support efforts aimed at rehabilitation and reconciliation. With this objective in view, she visited [[South Africa]] once more in 1903. She decided to set up Boer home industries and to teach young women [[Spinning (textiles)|spinning]] and [[weaving]]. | After Hobhouse had met the [[Boer]] generals she learned from them that the distress of the women and children in the [[concentration camp]]s had contributed to their final resolution to surrender to [[Britain]]. She saw it then as her mission to assist in healing the wounds inflicted by the war and to support efforts aimed at rehabilitation and reconciliation. With this objective in view, she visited [[South Africa]] once more in 1903. She decided to set up Boer home industries and to teach young women [[Spinning (textiles)|spinning]] and [[weaving]]. | ||

Ill health, however, from which she never recovered, forced her to return to England in 1908. She traveled to South Africa again in 1913 for the inauguration of the [[National Women's Monument]] in Bloemfontein, but had to stop at Beaufort West due to her failing health. | Ill health, however, from which she never recovered, forced her to return to England in 1908. She traveled to South Africa again in 1913 for the inauguration of the [[National Women's Monument]] in Bloemfontein, but had to stop at Beaufort West due to her failing health. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| Line 58: | Line 56: | ||

Hobhouse became an honorary citizen of [[South Africa]] for her humanitarian work there. Her house in St. Ives, Cornwall, now forms part of The Porthminster Hotel, where a commemorative plaque situated within what was her lounge, was unveiled by the South African High Commissioner [[Kent Durr]] as a tribute to her humanitarianism and heroism during the [[Anglo-Boer War]]. | Hobhouse became an honorary citizen of [[South Africa]] for her humanitarian work there. Her house in St. Ives, Cornwall, now forms part of The Porthminster Hotel, where a commemorative plaque situated within what was her lounge, was unveiled by the South African High Commissioner [[Kent Durr]] as a tribute to her humanitarianism and heroism during the [[Anglo-Boer War]]. | ||

| − | The southernmost town in Eastern [[Free State]] is named Hobhouse, after her. | + | The southernmost town in Eastern [[Free State]] is named Hobhouse, after her. as was a Spitj African Navy [[submarine]], the ''Emily Hobhouse''. |

==Publications== | ==Publications== | ||

Revision as of 23:37, 26 June 2007

Emily Hobhouse (April 9, 1860 — June 8, 1926) was a British welfare campaigner, who is primarily remembered for her work related to British [[concentration camp]s in South Africa. Despite criticism and hostility from the British government and media, she succeeded in bringing to the attention of the British public the appalling conditions inside the camps for Boer women and children during the Second Boer War, and bringing about positive change. Hobhouse became an honorary citizen of South Africa for her humanitarian work.

Life=

Emily Hobhouse was born on April 9, 186 in Liskeard, Cornwall, in Great Britain. She was the daughter of an Anglican rector, and sister of Leonard Hobhouse. Her mother died when she was 20, and she spent the next fourteen years looking after her father who was in poor health.

When her father died in 1895 she went to Minnesota, United States to perform welfare work amongst Cornish mineworkers living there, a trip organized by the wife of the Archbishop of Canterbury. There she became engaged to John Carr Jackson and the couple bought a ranch in Mexico. However, this did not prosper and the engagement was broken off. She returned to England in 1898 after losing most of her money in a speculative venture.

In 1899, at the outbreak of the Second Boer War, she became involved with the South African Conciliation Committee. It was there that she heard of the high mortality rate in the Boer concentration camps. Visiting them, she saw first hand the horrors. She publicized the problems and demanded reform. Her report, which remains a classic in its moving descriptions of the suffering of women and children, brought about change, but too late for too many victims.

Hobhouse was an avid opponent of the World War I and protested vigorously against it. Through her offices, thousands of women and children were fed daily for more than a year in central Europe after this war.

Hobhouse died in London in 1926 and her ashes were ensconced in a niche in the National Women's Monument at Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Work

When the Second Boer War broke out in October 1899, a Liberal MP, Leonard Courtney, invited Hobhouse to become secretary of the women's branch of the South African Conciliation Committee, of which he was president. Upon taking up her position, Hobhouse wrote:

It was late in the summer of 1900 that I first learned of the hundreds of Boer women that became impoverished and were left ragged by our military operations… the poor women who were being driven from pillar to post, needed protection and organized assistance.[1]

She set up the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children and sailed for South Africa on December 7, 1900 to supervise its distribution. At the time, she only knew about the concentration camp at Port Elizabeth, but on arrival found out about the many other camps (34 in total).

She arrived at the camp at Bloemfontein on January 24, 1901 and was shocked by the conditions she encountered:

They went to sleep without any provision having been made for them and without anything to eat or to drink. I saw crowds of them along railway lines in bitterly cold weather, in pouring rain - hungry, sick, dying and dead. Soap was an article that was not dispensed. The water supply was inadequate. No bedstead or mattress was procurable. Fuel was scarce and had to be collected from the green bushes on the slopes of the kopjes (small hills) by the people themselves. The rations were extremely meagre and when, as I frequently experienced, the actual quantity dispensed fell short of the amount prescribed, it simply meant famine.[2]

Hobhouse had persuaded the authorities to let her visit several camps and to deliver aid – her report on conditions at the camps, set out in her report to the Committee of the Distress Fund for South African Women and Children, entitled Report of a Visit to the Camps of Women and Children in the Cape and Orange River Colonies was delivered to the British government in June 1901.

What most distressed Hobhouse was the suffering of the undernourished children. Diseases such as measles, bronchitis, pneumonia, dysentery, and typhoid had invaded the camp with fatal results. In addition, overcrowding and bad unhygienic conditions, were the causes of a mortality rate that in the eighteen months during which the camps were in operation reached a total of 26,370, of which 24,000 were children under sixteen and infants. About 50 children died every day.

The following extracts from the report by Emily Hobhouse (1901) make very clear the extent of culpable neglect by the authorities:

It presses hardest on the children. They droop in the terrible heat, and with the insufficient unsuitable food; whatever you do, whatever the authorities do, and they are, I believe, doing their best with very limited means, it is all only a miserable patch on a great ill. Thousands, physically unfit, are placed in conditions of life which they have not strength to endure. In front of them is blank ruin…If only the British people would try to exercise a little imagination – picture the whole miserable scene. Entire villages rooted up and dumped in a strange bare place.

Above all one would hope that the good sense, if not the mercy, of the English people, will cry out against the further development of this cruel system which falls with crushing effect upon the old, the weak, and the children. May they stay the order to bring in more and yet more. Since Old Testament days was ever a whole nation carried captive?

Late in 1901 the camps ceased to receive new families and conditions improved in some camps; but the damage was done.

When Hobhouse requested soap for the people, she was told that soap is an article of luxury. She nevertheless succeeded, after a struggle, to have it listed as a necessity, together with straw, more tents, and more kettles in which to boil the drinking water. She distributed clothes and supplied pregnant women with mattresses and personal hygiene materials.

Hobhouse also visited camps at Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley, and Orange River.

When Hobhouse returned to England, she received scathing criticism and hostility from the British government and the media, but eventually succeeded in obtaining more funding to help the victims of the war. She also managed to successfully lobby the government for an investigation of the conditions in the camps. The British Liberal leader at the time, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, denounced what he called the "methods of barbarism." The British government eventually agreed to set up the Fawcett Commission to investigate her claims, under Millicent Fawcett, which corroborated her account of the shocking conditions.

Hobhouse returned to Cape Town in October 1901, but was not permitted to land and was eventually deported five days after arriving, no reason being given. Hobhouse then went to France where she wrote the book The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell on what she saw during the war.

After Hobhouse had met the Boer generals she learned from them that the distress of the women and children in the concentration camps had contributed to their final resolution to surrender to Britain. She saw it then as her mission to assist in healing the wounds inflicted by the war and to support efforts aimed at rehabilitation and reconciliation. With this objective in view, she visited South Africa once more in 1903. She decided to set up Boer home industries and to teach young women spinning and weaving.

Ill health, however, from which she never recovered, forced her to return to England in 1908. She traveled to South Africa again in 1913 for the inauguration of the National Women's Monument in Bloemfontein, but had to stop at Beaufort West due to her failing health.

Legacy

Hobhouse became an honorary citizen of South Africa for her humanitarian work there. Her house in St. Ives, Cornwall, now forms part of The Porthminster Hotel, where a commemorative plaque situated within what was her lounge, was unveiled by the South African High Commissioner Kent Durr as a tribute to her humanitarianism and heroism during the Anglo-Boer War.

The southernmost town in Eastern Free State is named Hobhouse, after her. as was a Spitj African Navy submarine, the Emily Hobhouse.

Publications

- Hobhouse, Emily. 1901. Report of a visit to the camps of women and children in the Cape and Orange River colonies. London: Friars Printing Association, Ltd.

- Hobhouse, Emily. 1903. After the war: Letters from Miss Emily Hobhouse respecting the Transvaal and Orange River colonies. London: National Press Agency.

- Hobhouse, Emily. 1924. War without glamour: or, Women's war experiences written by themselves, 1899-1902. Bloemfontein: Nasionale Pers Beperk.

- Hobhouse, Emily. 1929. Emily Hobhouse: A memoir. London: J. Cape.

- Hobhouse, Emily. 1984. Boer War letters. Human & Rousseau. ISBN 0798118237

- Hobhouse, Emily. 2007 (original published in 1902). The brunt of war and where it fell. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1432535897

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Emily Hobhouse. Anglo-Boar War Museum, on http://www.anglo-boer.co.za. Retrieved on June 23, 2007, <http://www.anglo-boer.co.za/emily.html>

- Fockens, Johanna. 1997. Emily Hobhouse. Protea Boekhuis. ISBN 0620220430

- Lee, Emanuel. 1986. To the bitter end. New York: Viking. ISBN 0670801437

- Pakenham, Thomas. 1992. The Boer War. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0380720019

- Roberts, Brian. 1991. Those bloody women: Three heroines of the Boer War. London: J. Murray. ISBN 0719548586

- Terblanche, Annette. 1948. Emily Hobhouse. Johannesburg: Afrikaanse pers-boekhandel.

External links

- Australia and the Boer War – On the history of British engagement in South Africa Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- The Boer Wars – On the history of the wars Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- Emily Hobhouse – Biography on Anglo-Boer War Museum website Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- Emily Hobhouse – Biography on Spartacus Schoolnet Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- Emily Hobhouse – Biography on "Special South Africans" website Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- The "hysterical" Emily Hobhouse and Boer war concentration camp controversy – Article by Hasian, Marouf Jr. (2003) Retrieved June 25, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Emily Hobhouse Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Emily Hobhouse Retrieved June 25, 2007.