Difference between revisions of "Clinical depression" - New World Encyclopedia

(copied from wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (157 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | [[ | + | {{Infobox medical condition (new) |

| − | [[ | + | | name = Clinical depression |

| − | + | | image = File:Vincent Willem van Gogh 002.jpg | |

| + | | alt = | ||

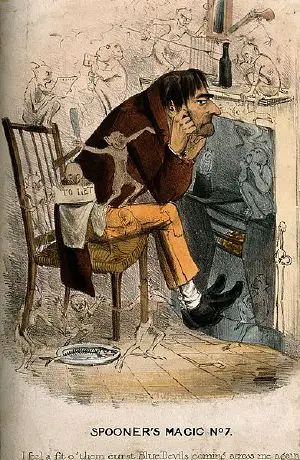

| + | | caption = ''[[At Eternity's Gate|Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate)]]''<br />by [[Vincent van Gogh]] (1890) | ||

| + | | field = [[Psychiatry]], [[clinical psychology]] | ||

| + | | synonyms = Major depressive disorder, major depression, unipolar depression, unipolar disorder, recurrent depression | ||

| + | | symptoms = [[depression (mood)|Low mood]], low [[self-esteem]], [[Anhedonia|loss of interest]] in normally enjoyable activities, low energy, [[pain]] without a clear cause<ref name=NIH2016>[https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression Depression] ''National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)''. Retrieved October 10, 2022.</ref> | ||

| + | | complications = [[Self-harm]], [[suicide]]<ref name=Rich2014>C. Steven Richards and Michael W. O'Hara (eds.), ''The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity'' (Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0199797004).</ref> | ||

| + | | onset = 20s<ref name=DSM-5>American Psychiatric Association, ''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5'' (American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2013, ISBN 978-0890425558).</ref> | ||

| + | | duration = > 2 weeks<ref name=NIH2016/> | ||

| + | | causes = Environmental ([[Psychological trauma|adverse life experiences]], stressful life events), [[Genetics|genetic]] and psychological factors<ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| + | | risks = [[Family history (medicine)|Family history]], major life changes, certain [[medication]]s, [[chronic health problem]]s, [[substance use disorder]]<ref name=NIH2016/><ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| + | | diagnosis = | ||

| + | | differential = [[Bipolar disorder]], [[ADHD]], [[sadness]]<ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| + | | prevention = | ||

| + | | treatment = [[Psychotherapy]], [[antidepressant medication]], [[electroconvulsive therapy]], [[exercise]]<ref name=NIH2016/> | ||

| + | | medication = [[Antidepressant]]s | ||

| + | | prognosis = | ||

| + | | frequency = | ||

| + | | deaths = | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''Clinical Depression''', also known as '''Major Depressive Disorder''' ('''MDD'''), is a [[mental disorder]] characterized by pervasive [[depression (mood)|low mood]], low [[self-esteem]], and [[anhedonia|loss of interest or pleasure]] in normally enjoyable activities over a protracted period of time. | ||

| − | + | The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the person's reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a [[mental status examination]]. The course of the disorder varies widely, from one episode lasting months to a lifelong disorder with recurrent [[major depressive episode]]s. Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of [[genetics|genetic]], environmental, and psychological factors. Risk factors include a [[Family history (medicine)|family history]] of the condition, major life changes, certain medications, [[chronic health problem]]s, and [[substance use disorder]]s. Those suffering from clinical depression are typically treated with [[psychotherapy]] and [[antidepressant medication]]. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Despite efforts to educate the public about [[mental disorder]]s, social stigma continues to make it difficult both for those suffering from serious depression to admit their problems and for health professionals to diagnose and treat them. The view held by some psychiatrists that such depression is merely a social construct or imagined illness that is inappropriately regarded as an actual disease compounds these difficulties. Compassion as well as support for effective treatment is needed to allow those suffering from depression to receive appropriate and effective treatment so that they may be successful members of society. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Terminology== | |

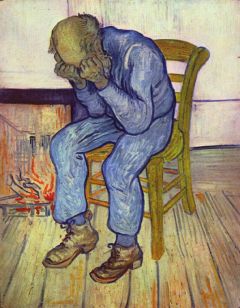

| + | [[File:Abraham Lincoln O-60 by Brady, 1862.jpg|thumb|300px|The 16th [[President of the United States|American president]], [[Abraham Lincoln]], had "[[Depression (mood)|melancholy]]", a condition that now may be referred to as "clinical depression."<ref>Joshua Wolf Shenk, [https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2005/10/lincolns-great-depression/304247/ Lincoln's Great Depression] ''The Atlantic'', October 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref>]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | '''Clinical depression''', also known as '''Major depressive disorder''' ('''MDD'''), is classified as a [[mental disorder]]. However, the term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is often used to mean the syndrome but may refer to other [[mood disorder]]s or simply to a low mood. People's conceptualizations of depression vary widely: "Because of the lack of scientific certainty," one commentator has observed, "the debate over depression turns on questions of language. What we call it—'disease,' 'disorder,' 'state of mind'—affects how we view, diagnose, and treat it."<ref> Field Maloney, [https://slate.com/culture/2005/11/the-depression-wars.html The Depression Wars: Would Honest Abe Have Written the Gettysburg Address on Prozac?] ''Slate'', November 3, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref> |

==History== | ==History== | ||

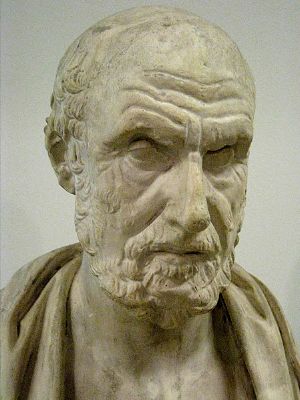

| + | [[File:Hippocrates pushkin02.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Diagnoses of depression go back at least as far as [[Hippocrates]].]] | ||

| + | The Ancient Greek physician [[Hippocrates]] described a syndrome of [[melancholia]] ({{lang|grc|μελαγχολία}}, {{transl|grc|melankholía}}) as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms; he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.<ref>Hippocrates, ''Aphorisms'', Section 6.23.</ref> It was a similar but far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions, and obsessions were included.<ref name= Radden2003>Jennifer Radden, [https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-07847-007 Is This Dame Melancholy? Equating Today's Depression and Past Melancholia] ''Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology'' 10(1) (2003): 37–52. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | The term "depression" was derived from the Latin verb {{lang|la|deprimere}}, meaning "to press down."<ref>[https://www.dictionary.com/browse/depress Depress] Dictionary.com''. Retrieved October 14, 2022. </ref> From the fourteenth century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author [[Richard Baker (chronicler)|Richard Baker's]] ''Chronicle'' to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit," and by English author [[Samuel Johnson's health|Samuel Johnson]] in a similar sense in 1753.<ref name=Wolpert>Lewis Wolpert, ''Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression'' (Free Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0684870588).</ref> An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist [[Louis Delasiauve]] in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function.<ref>G.E. Berrios, [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/abs/melancholia-and-depression-during-the-19th-century-a-conceptual-history/5257E8A5BA6C993A023F32462378CC92 Melancholia and depression during the 19th century: a conceptual history] ''The British Journal of Psychiatry'' 153(3) (September 1988): 298–304. Retrieved October 14, 2022. </ref> Since [[Aristotle]], melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. The newer concept abandoned these associations and through the nineteenth century, and became more associated with women.<ref name=Radden2003/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Although "melancholia" remained the dominant diagnostic term, "depression" gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist [[Emil Kraepelin]] may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as "depressive states."<ref name=Wolpert/> [[Freud]] likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper ''Mourning and Melancholia''. He theorized that [[object (philosophy)|objective]] loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in [[subject (philosophy)|subjective]] loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an [[unconscious mind|unconscious]], [[narcissism|narcissistic]] process called the "libidinal [[cathexis]]" of the [[Id, ego and super-ego|ego]]. Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised.<ref>Sigmund Freud, ''On Murder, Mourning, and Melancholia'' (Penguin Classic, 2005, ISBN 978-0141183794).</ref> He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.<ref name=Radden2003/> [[Adolf Meyer (psychiatrist)|Adolf Meyer]] put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing ''reactions'' in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term "depression" should be used instead of "melancholia."<ref name="Lewis1934">A.J. Lewis, [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-mental-science/article/melancholia-a-historical-review/1DE306A9C4BE5D7B3732DFBBD18418E6 Melancholia: A historical review] ''Journal of Mental Science'' 80(328) (January 1934): 1-42. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | The first version of the American Psychiatric Association's ''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders'' (''DSM-I'') published in 1952, contained "depressive reaction" and the ''DSM-II'', published in 1968, contained "depressive neurosis." These were defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within the area of "Major affective disorders."<ref>Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics of the American Psychiatric Association, ''Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-II'' (American Psychiatric Association, 1968), 36–37, 40. </ref> | |

| − | + | The term "Major Depressive Disorder'' was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria," building on the earlier [[Feighner Criteria]]).<ref name= Spitzer>Robert L. Spitzer, [http://www.garfield.library.upenn.edu/classics1989/A1989U309700001.pdf The Development of Diagnostic Criteria in Psychiatry] ''Research diagnostic criteria (RDC)'', 1975. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref> The [[American Psychiatric Association]] added "major depressive disorder" to the ''DSM-III'', published in 1980, as a split of the previous [[depressive neurosis]] in the ''DSM-II'', which also encompassed the conditions now known as [[dysthymia]] (or Persistent Depressive Disorder or PDD) and [[adjustment disorder with depressed mood]].<ref>Johan Rosqvist and Michel Hersen (eds.), ''Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment, Volume 1: Adults'' (Wiley, 2007, ISBN 978-0471779995).</ref> | |

| − | + | To maintain consistency, the [[World Health Organization]]'s ''International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)'' used the same criteria, with only minor alterations. It used the ''DSM'' diagnostic threshold to mark a "mild depressive episode," adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.<ref name="DSMvsICD">Alan M. Gruenberg, Reed D. Goldstein, and Harold Alan Pincus, "Classification of Depression: Research and Diagnostic Criteria: DSM-IV and ICD-10" in Julio Licinio and Ma-Li Wong (eds.), ''Biology of Depression: From Novel Insights to Therapeutic Strategies'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005, ISBN 3527307850), 1–12.</ref> The ancient idea of "melancholia: still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype. | |

| − | : | + | ==Symptoms== |

| + | [[File:A woman diagnosed as suffering from melancholia. Colour lith Wellcome L0026686.jpg|thumb|300px\An 1892 lithograph of a woman diagnosed with [[melancholia]]]] | ||

| + | Major depression significantly affects a person's family and [[Social predictors of depression|personal relationships]], work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health.<ref name=NIMHPub>[https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/publications/depression/21-mh-8079-depression_0.pdf Depression] ''National Institute of Mental Health'' (NIMH), 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2022. </ref> A person having a [[major depressive episode]] usually exhibits a low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in previously enjoyable activities. They may be preoccupied with—or [[Rumination (psychology)|ruminate]] over—thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness or hopelessness.<ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| − | + | Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory, withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced [[libido|sex drive]], irritability, and thoughts of death or [[suicide]]. [[Insomnia]] is common; in the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep. [[Hypersomnia]], or oversleeping, can also happen. In severe cases, depressed people may have [[psychosis|psychotic]] symptoms. These symptoms include [[delusion]]s or, less commonly, [[hallucination]]s, usually unpleasant.<ref name=DSM-5/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as [[fatigue]], headaches, or digestive problems. [[Appetite]] often decreases, resulting in weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur. Family and friends may notice [[psychomotor agitation|agitation]] or [[psychomotor retardation|lethargy]]. Elderly people may not present with classical depressive symptoms; they may have [[Cognition#Psychology|cognitive]] symptoms of recent onset, such as forgetfulness, and a more noticeable slowing of movements. Depressed children may often display an irritable rather than a depressed mood; most lose interest in school and show a steep decline in academic performance.<ref name=DSM-5/> | |

| − | + | ==Causes== | |

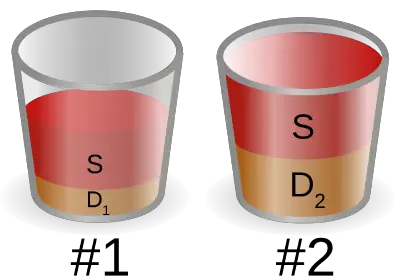

| + | [[File:Diathesis_stress_model_cup_analogy.png|thumb|400px|A cup analogy demonstrating the [[diathesis–stress model]] that under the same amount of stressors, person 2 is more vulnerable than person 1, because of their predisposition.<ref>Benjamin L. Hankin and John R.Z. Abela, ''Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective'' (SAGE Publications, Inc, 2005, ISBN 1412904900).</ref>]] | ||

| + | Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of [[genetics|genetic]], environmental, and psychological factors: In other words, biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression. Risk factors include a [[Family history (medicine)|family history]] of the condition, major life changes, certain medications, [[chronic health problem]]s, and [[substance use disorder]]s.<ref name=NIH2016/><ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| − | + | The [[diathesis–stress model]] specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or [[Diathesis (medicine)|diathesis]], is activated by stressful life events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either [[genetics|genetic]], implying an interaction between [[nature and nurture]], or [[Schema (psychology)|schematic]], resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.<ref>George M. Slavich, [https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/deconstructing-depression-a-diathesis-stress-perspective Deconstructing depression: A diathesis-stress perspective] ''Association for Psychological Science (APS)'', September 3, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | American psychiatrist [[Aaron Beck]] suggested that a triad of automatic and spontaneous negative thoughts about the [[Self-image|self]], the [[Social environment|world or environment]], and the future may lead to other depressive signs and symptoms.<ref name=Beck>Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery, ''Cognitive Therapy of Depression'' (The Guilford Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0898629194).</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Adverse childhood experiences]] (incorporating [[Child abuse|childhood abuse]], neglect and [[Dysfunctional family|family dysfunction]]) markedly increase the risk of major depression.<ref name=DSM-5/> Childhood trauma also correlates with severity of depression, poor responsiveness to treatment, and length of illness. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | There has been a continuing discussion of whether neurological disorders and mood disorders may be linked to [[creativity]], a discussion that goes back to [[Aristotle|Aristotelian]] times.<ref>Nancy C. Andreasen, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181877/ The relationship between creativity and mood disorders] ''Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience'' 10(2) (2008): 251–255. Retrieved October 16, 2022.</ref> British literature gives many examples of reflections on depression.<ref> Carol F. Heffernan, ''The Melancholy Muse: Chaucer, Shakespeare and Early Medicine'' (Duquesne University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0820702629). </ref> English philosopher [[John Stuart Mill]] experienced a several-months-long period of what he called "a dull state of nerves," when one is "unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent." He quoted English poet [[Samuel Taylor Coleridge]]'s "Dejection" as a perfect description of his case: "A grief without a pang, void, dark and drear, / A drowsy, stifled, unimpassioned grief, / Which finds no natural outlet or relief / In word, or sigh, or tear."<ref>John Stuart Mill, ''Autobiography'' (Adamant Media Corporation, 2000, ISBN 978-1421242002).</ref> English writer [[Samuel Johnson]] used the term "the black dog" in the 1780s to describe his own depression, and it was subsequently popularized by British Prime Minister Sir [[Winston Churchill]], who also had the disorder.<ref>Kerrie Eyers (ed.), ''Tracking the Black Dog'' (University of New South Wales, 2006, ISBN 978-0868408125). </ref> | |

| − | + | Depression can also come secondary to a chronic or terminal medical condition, such as [[HIV/AIDS]] or [[asthma]], and may be labeled "secondary depression."<ref>Paula J. Clayton and C.E. Lewis, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6455456/ The significance of secondary depression] ''Journal of Affective Disorders'' 3(1) (March 1981): 25–35. Retrieved October 16, 2022.</ref> It is unknown whether the underlying diseases induce depression through effect on quality of life, or through shared etiologies (such as degeneration of the [[basal ganglia]] in [[Parkinson's disease]] or immune dysregulation in asthma). Depression may also be [[iatrogenic]] (the result of [[healthcare]]), such as depression as a side effect of prescribed medications. Depression occurring after giving birth, [[postpartum depression]], is thought to be the result of [[Hormone|hormonal]] changes associated with [[pregnancy]]. [[Seasonal affective disorder]] is a type of depression associated with seasonal changes in sunlight where people who have normal mental health throughout most of the year exhibit depressive symptoms at the same time each year, most often in winter. | |

| − | + | ==Diagnosis== | |

| + | There is no laboratory test for clinical depression, and so diagnosis is based on the person's reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a [[mental status examination]], although tests may be conducted to rule out physical conditions that can cause similar symptoms.<ref> Lauren L. Patton and Michael Glick (eds.), ''The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions 2nd Edition'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015, ISBN 978-1118924402).</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Clinical assessment=== | |

| + | [[File:A wretched man with an approaching depression; represented b Wellcome V0011145.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Caricature of a man with depression]] | ||

| + | A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained [[general practitioner]], or by a [[psychiatrist]] or [[psychologist]], who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, family history, and alcohol and drug use. The assessment also includes a [[mental state examination]], which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, in particular the presence of themes of hopelessness or [[pessimism]], [[self-harm]] or [[suicide]], and an absence of positive thoughts or plans.<ref name=NIMHPub/> | ||

| − | + | [[Rating scale]]s are not used to diagnose depression, but they provide an indication of the severity of symptoms for a time period, so a person who scores above a given cut-off point can be more thoroughly evaluated for a depressive disorder diagnosis. Several rating scales are used for this purpose, including the [[Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression]], the [[Beck Depression Inventory]], and the [[Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised]]. | |

| − | + | Specialist mental health services are rare in rural areas, especially in developing countries, and thus diagnosis and management is left largely to [[primary care|primary-care]] clinicians. Since primary-care physicians have more difficulty with under-recognition and under-treatment of depression compared to psychiatrists, they often miss cases where people experience physical symptoms accompanying their depression. | |

| − | + | A doctor generally performs a medical examination and selected investigations to rule out other causes of depressive symptoms. These can include blood tests to exclude [[hypothyroidism]] and [[Metabolic disorder|metabolic disturbance]], or a [[systemic infection]] or chronic disease.[[Testosterone]] levels may be evaluated to diagnose [[hypogonadism]], a cause of depression in men. Adverse affective reactions to medications or alcohol misuse may be ruled out, as well. Subjective cognitive complaints appear in older depressed people, but they can also be indicative of the onset of a [[dementia|dementing disorder]], such as [[Alzheimer's disease]], which can be rule out through [[Neuropsychological assessment|Cognitive testing]] and brain imaging. | |

| − | + | ===DSM and ICD criteria=== | |

| + | The most widely used criteria for diagnosing depressive conditions are found in the [[American Psychiatric Association]]'s ''[[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]]'' (DSM) and the [[World Health Organization]]'s ''[[ICD|International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems]]'' (ICD). The latter system is typically used in European countries, while the former is used in the US and many other non-European nations, and the authors of both have worked towards conforming one with the other. Both DSM and ICD mark out typical (main) depressive symptoms.<ref name="DSMvsICD" /> | ||

| − | === | + | ;ICD-11 |

| − | + | Under mood disorders, ICD-11 classifies major depressive disorder as either "single episode depressive disorder" (where there is no history of depressive episodes, or of mania)<ref name=ICD-11Single>[https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/578635574 6A70 Single episode depressive disorder] ''ICD-11''. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> or "recurrent depressive disorder" (where there is a history of prior episodes, with no history of mania).<ref name=ICD-iiRecurrent> [https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1194756772 6A71 Recurrent depressive disorder] ''ICD-11''. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> These two disorders are classified as "Depressive disorders," in the category of "Mood disorders". The symptoms, which must affect work, social, or domestic activities and be present nearly every day for at least two weeks, are a depressed mood or [[anhedonia]], accompanied by other symptoms such as "difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, changes in appetite or sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and reduced energy or fatigue."<ref name=ICD-11Single/><ref name=ICD-iiRecurrent/> The ICD-11 system allows further specifiers for the current depressive episode: the severity (mild, moderate, severe, unspecified); the presence of psychotic symptoms (with or without psychotic symptoms); and the degree of remission if relevant (currently in partial remission, currently in full remission).<ref name=ICD-11Single/><ref name=ICD-iiRecurrent/> | |

| − | + | ;DSM-5 | |

| + | Major depressive disorder is classified as a mood disorder in DSM-5. There are two main depressive symptoms: a depressed mood, and loss of interest/pleasure in activities (anhedonia). These symptoms, as well as five out of the nine more specific symptoms listed, must frequently occur for more than two weeks (to the extent in which they impair functioning) for the diagnosis. Further qualifiers are used to classify both the episode itself and the course of the disorder. The category [[Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified|Unspecified Depressive Disorder]] is diagnosed if the depressive episode's manifestation does not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.<ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| − | + | A major depressive episode is characterized by the presence of a severely depressed mood that persists for at least two weeks. Episodes may be isolated or recurrent and are categorized as mild (few symptoms in excess of minimum criteria), moderate, or severe (marked impact on social or occupational functioning). An episode with psychotic features—commonly referred to as "[[psychotic depression]]"—is automatically rated as severe. If the person has had an episode of [[mania]] or [[hypomania|markedly elevated mood]], a diagnosis of [[bipolar disorder]] is made instead. | |

| − | + | [[Grief|Bereavement]] is not an exclusion criterion in DSM-5, and it is up to the clinician to distinguish between normal reactions to a loss and MDD. Excluded are a range of related diagnoses, including [[dysthymia]], which involves a chronic but milder mood disturbance; [[recurrent brief depression]], consisting of briefer depressive episodes; [[minor depressive disorder]], whereby only some symptoms of major depression are present; and [[Adjustment disorder|adjustment disorder with depressed mood]], which denotes low mood resulting from a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor.<ref name=DSM-5/> | |

| − | + | The DSM-5 recognizes six further subtypes of MDD, called "specifiers," in addition to noting the length, severity, and presence of psychotic features:<ref name=DSM-5/> | |

| + | * "[[Melancholic depression]]" is characterized by a loss of pleasure in most or all activities, a failure of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, a quality of depressed mood more pronounced than that of [[grief]] or loss, a worsening of symptoms in the morning hours, early-morning waking, [[psychomotor retardation]], excessive weight loss (not to be confused with [[anorexia nervosa]]), or excessive guilt. | ||

| + | * "[[Atypical depression]]" is characterized by mood reactivity (paradoxical anhedonia) and positivity, significant [[weight gain]] or increased appetite (comfort eating), excessive sleep or sleepiness ([[hypersomnia]]), a sensation of heaviness in limbs known as leaden paralysis, and significant long-term social impairment as a consequence of hypersensitivity to perceived [[social rejection|interpersonal rejection]]. | ||

| + | * "[[Catatonia|Catatonic]] depression" is a rare and severe form of major depression involving disturbances of motor behavior and other symptoms. Here, the person is mute and almost stuporous, and either remains immobile or exhibits purposeless or even bizarre movements. Catatonic symptoms also occur in [[schizophrenia]] or in manic episodes, or may be caused by [[neuroleptic malignant syndrome]]. | ||

| + | *"Depression with [[Anxiety|anxious]] distress" was added into the DSM-5 as a means to emphasize the common co-occurrence between depression or [[mania]] and anxiety, as well as the risk of suicide of depressed individuals with anxiety. | ||

| + | *"Depression with [[Postpartum depression|peri-partum]] onset" refers to the intense, sustained, and sometimes disabling depression experienced by women after giving birth or while a woman is pregnant. To qualify as depression with peripartum onset, onset must occur during pregnancy or within one month of delivery. | ||

| + | * "[[Seasonal affective disorder]]" (SAD) is a form of depression in which depressive episodes come on in the autumn or winter, and resolve in spring. The diagnosis is made if at least two episodes have occurred in colder months with none at other times, over a two-year period or longer. | ||

| − | + | ===Differential diagnoses=== | |

| + | Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, [[medications]], and [[substance use disorder]]s. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a [[mood disorder due to a general medical condition]]. This condition is determined based on history, laboratory findings, or [[physical examination]]. When the depression is caused by a medication, non-medical use of a psychoactive substance, or exposure to a [[toxin]], it is then diagnosed as a specific mood disorder (previously called ''substance-induced mood disorder'').<ref name=DSM-5/> | ||

| − | + | To confirm major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, [[adjustment disorder]] with depressed mood, or [[bipolar disorder]]. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression. [[Adjustment disorder|Adjustment disorder with depressed mood]] is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.<ref name=DSM-5/> | |

| − | + | ===Cultural differences=== | |

| + | There are cultural differences in the extent to which serious depression is considered an illness requiring personal professional treatment, or an indicator of something else, such as the need to address social or moral problems, the result of biological imbalances, or a reflection of individual differences in the understanding of distress that may reinforce feelings of powerlessness, and emotional struggle.<ref>Alison Karasz, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15652693/ Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression] ''Social Science & Medicine'' 60(7) (Aoruk 2995): 1625–1635. Retrieved October 14, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | ''[[ | + | A diagnosis of illness is less common in some countries, such as China. It has been suggested that the Chinese traditionally deny or [[Somatization|somatize]] emotional depression. Alternatively, it may be that Western cultures reframe and elevate some expressions of human distress to disorder status. Australian professor [[Gordon Parker (psychiatrist)|Gordon Parker]] and others have argued that the Western concept of depression [[Medicalization|medicalizes]] sadness or misery.<ref>Gordon Parker, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1949440/ Is depression overdiagnosed? Yes] ''BMJ'' 335(7615) (August 2007): 328. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> Similarly, Hungarian-American psychiatrist [[Thomas Szasz]] and others argue that depression is a metaphorical illness that is inappropriately regarded as an actual disease,<ref>Warren Steibel, [http://www.szasz.com/isdepressionadiseasetranscript.html Is depression a disease?] ''Debatesdebates'', May 13, 1998, Retrieved October 17, 2022. </ref> or that there is a failure to take into consideration the influence of social constructs.<ref> Dan G. Blazer, ''The Age of Melancholy: "Major Depression" and its Social Origin'' (Routledge, 2005, ISBN 978-0415951883).</ref> |

| − | + | ==Management== | |

| + | The pathophysiology of depression is not completely understood. The most common and effective treatments are [[psychotherapy]], medication, and [[electroconvulsive therapy]] (ECT); a combination of treatments being the most effective approach. | ||

| − | + | [[American Psychiatric Association]] treatment guidelines recommend that initial treatment should be individually tailored based on factors including severity of symptoms, co-existing disorders, prior treatment experience, and personal preference. Options may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, exercise, ECT, [[transcranial magnetic stimulation]] (TMS), or [[light therapy]]. Antidepressant medication is recommended as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, and should be given to all people with severe depression unless ECT is planned.<ref name=APAGuideline>[https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd-1410197717630.pdf Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Third Edition] ''American Psychiatric Association'', 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Talk therapies=== | |

| + | Talk therapy, or [[psychotherapy]] can be delivered to individuals, groups, or families by mental health professionals, including psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical [[social work]]ers, counselors, and psychiatric nurses. With more complex and chronic forms of depression, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be used. | ||

| − | + | The most commonly used form of psychotherapy for depression is [[Cognitive Behavioral Therapy]] (CBT), which teaches clients to challenge self-defeating, but enduring ways of thinking (cognitions) and change counter-productive behaviors. CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) are preferred treatments for adolescent depression; in people under 18, according to the [[National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence]], medication should be offered only in conjunction with a psychological therapy, such as CBT, [[Interpersonal psychotherapy|interpersonal therapy]], or [[family therapy]].<ref>National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134/chapter/Recommendations How to use antidepressants in children and young people] ''Depression in children and young people: identification and management NICE guideline'', June 25, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2022. </ref> Several variants of cognitive behavior therapy have been used in treating depression, the most notable being [[rational emotive behavior therapy]]<ref name=Beck/> and [[mindfulness-based cognitive therapy]].<ref>Helen F. Coelho, Peter H. Canter, and Edzard Ernst, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18085916/ Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: evaluating current evidence and informing future research] ''Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology'' 75(6) (December 2007): 1000–1005. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Psychoanalysis]], founded by [[Sigmund Freud]], emphasizes the resolution of [[unconscious]] mental conflicts, and has been used to treat patients with major depression. A more widely practiced therapy, called [[psychodynamic psychotherapy]], is in the tradition of psychoanalysis but less intensive, meeting once or twice a week. It also tends to focus more on the person's immediate problems, and has an additional social and interpersonal focus.<ref name=Barlow>David H. Barlow, Vincent Mark Durand, and Stefan G. Hofmann, ''Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach (8th edition)'' (Cengage Learning, 2017, ISBN 978-1305950443).</ref> | |

| − | === | + | ===Antidepressants=== |

| − | + | Antidepressants are commonly prescribed to treat major depressive disorder. The treatment is usually continued for 16 to 20 weeks after remission, to minimize the chance of recurrence, and even up to one year of continuation is often recommended. People with chronic depression may need to take medication indefinitely to avoid relapse.<ref name=NIMHPub/> | |

| − | + | The UK [[National Institute for Health and Care Excellence]] (NICE) guidelines indicate that antidepressants should not be routinely used for the initial treatment of mild depression, because the risk to benefit ratio is poor. The guidelines recommended that antidepressant treatment be considered for: | |

| − | + | * People with a history of moderate or severe depression | |

| + | * Those with mild depression that has been present for a long period | ||

| + | * As a second-line treatment for mild depression that persists after other interventions | ||

| + | * As a first-line treatment for moderate or severe depression | ||

| − | + | The guidelines further note that antidepressant treatment should be used in combination with psychosocial interventions in most cases, should be continued for at least six months to reduce the risk of relapse, and that [[selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor]] (SSRIs) are typically better tolerated than other antidepressants.<ref>National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH), ''Depression: The NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults'' (RCPsych Publications, 2010, ISBN 978-1904671855). </ref> To find the most effective antidepressant medication with minimal side-effects, the dosages can be adjusted, and if necessary, combinations of different classes of antidepressants can be tried. | |

| − | + | [[American Psychiatric Association]] treatment guidelines recommended antidepressant medication as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, that should be given to all people with severe depression unless ECT is planned.<ref name=APAGuideline/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Electroconvulsive therapy=== | ===Electroconvulsive therapy=== | ||

| − | Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), | + | [[Electroconvulsive therapy]] (ECT), along with antidepressants and psychotherapy, is one of the three major treatments of depression. It has been found to reduce depression symptoms regardless of whether antidepressants are involved. ECT is a standard [[psychiatry|psychiatric]] treatment in which [[seizure]]s are electrically induced in a person with depression to provide relief from psychiatric illnesses. ECT is used with [[informed consent]] as a last line of intervention for major depressive disorder.<ref>Ming Li, Xiaoxiao Yao, et al, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7044268/ Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy on Depression and Its Potential Mechanism] ''Frontiers in Psychology'', 11(80) (2020). Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Lifestyle=== | |

| + | [[Physical exercise]] has been found to be effective for major depression, and may be recommended to people who are willing, motivated, and healthy enough to participate in an exercise program as treatment. Sleep and diet may also play a role in depression, and interventions in these areas may be an effective add-on to conventional methods.<ref>Adrian L. Lopresti, Sean D. Hood, Peter D. Drummond, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23415826/ A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: diet, sleep and exercise] ''Journal of Affective Disorders'' 148(1) (May 2013): 12–27. Retrieved October 17, 2022. </ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Prognosis== | |

| + | Major depressive episodes often resolve over time, whether or not they are treated. However, the majority of those with a first major depressive episode will have at least one more during their lifetime. | ||

| − | === | + | ===Ability to work=== |

| − | + | Depression may affect people's ability to work. The combination of usual clinical care and support with return to work (like working less hours or changing tasks) leads to fewer depressive symptoms and improved work capacity. Additional psychological interventions (such as online cognitive behavioral therapy) as well as streamlining care or adding specific providers for depression care improve ability to work. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Life expectancy and the risk of suicide=== | |

| + | Depressed individuals have a shorter [[life expectancy]] than those without depression, in part because people who are depressed are at risk of dying of [[suicide]]. Approximately half the people who die of suicide have a mood disorder such as major depression, and the risk is especially high if a person has a marked sense of hopelessness or has both depression and [[borderline personality disorder]].<ref name=Barlow/><ref> Stephen Strakowski and Erik Nelson, ''Major Depressive Disorder'' (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0190206185) </ref> | ||

| − | + | Those suffering from major depression also have a higher [[mortality rate|rate of dying]] from other causes. People with major depression are at risk death from [[cardiovascular disease]], especially since they less likely to follow medical recommendations for its treatment and prevention, further increasing their risk of medical complications. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Epidemiology== | |

| + | Major depressive disorder affects millions of people throughout the world. Women are more affected than men, although although it is unclear why this is so. | ||

| − | + | People are most likely to develop their first depressive episode between the ages of 30 and 40, and there is a second, smaller peak of incidence between ages 50 and 60.<ref>W.W. Eaton et al, Natural history of Diagnostic Interview Schedule/DSM-IV major depression. The Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up] ''Archives of General Psychiatry'' 54(11) (November 1997): 993–999. Retrieved October 17, 2022.</ref> The risk of major depression is increased with neurological conditions such as [[stroke]], [[Parkinson's disease]], or [[multiple sclerosis]], and during the first year after childbirth.<ref>Hugh Rickards, [https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/76/suppl_1/i48 Depression in neurological disorders: Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke] ''Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry'' 76(Suppl 1) (March 2005): i48–52. Retrieved October 17, 2022. </ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Comorbidity=== | ||

| + | Major depression frequently [[Comorbidity|co-occurs]] with other psychiatric problems, as well as increased rates of [[alcohol]] and [[drug abuse]]. For example, [[Post-traumatic stress disorder]] and depression often co-occur.<ref name=NIMHPub/> Depression often occurs in individuals with [[attention deficit hyperactivity disorder]] (ADHD), complicating the diagnosis and treatment of both.<ref> Edward M. Hallowell and John J. Ratey, ''Delivered from Distraction: Getting the Most out of Life with Attention Deficit Disorder'' (Ballantine Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0345442314).</ref> | ||

| − | + | [[Anxiety disorder|anxiety]] symptoms can have a major impact on the course of a depressive illness, with delayed recovery, increased risk of relapse, greater disability, and increased suicidal behavior.<ref>Robert M.A. Hirschfeld, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15014592/ The Comorbidity of Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders: Recognition and Management in Primary Care] ''Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry'' 3(6) (December 2001): 244–254. Retrieved October 18, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | Depression and [[pain]] often co-occur, although it is under-recognized, and therefore under-treated, in patients presenting with pain. Depression often coexists with physical disorders common among the elderly, such as [[stroke]], other [[cardiovascular diseases]], [[Parkinson's disease]], and [[chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]]. | |

| − | == | + | ==Social stigma== |

| − | [[ | + | Historical figures were often reluctant to discuss or seek treatment for depression due to [[social stigma]] about the condition, or due to ignorance of diagnosis or treatments. Nevertheless, analysis or interpretation of letters, journals, artwork, writings, or statements of family and friends of some historical personalities has led to the presumption that they may have had some form of depression. People who may have had depression include English author [[Mary Shelley]],<ref>Miranda Seymour, ''Mary Shelley'' (Grove Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0802139481).</ref> American-British writer [[Henry James]],<ref> Leon Edel (ed.), ''The Letters of Henry James 1883–1895'' (Belknap Press, 1980, ISBN 978-0674387829).</ref> and American president [[Abraham Lincoln]].<ref>Michael Burlingame, ''The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln'' (University of Illinois Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0252066672).</ref> |

| − | + | Some pioneering psychologists, such as Americans [[William James]]<ref>William James, ''Letters of William James'' (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2003, ISBN 978-0766175662)</ref> and [[John B. Watson]],<ref>David Cohen, ''J.B. Watson: The Founder of Behaviourism'' (Routledge Kegan & Paul, 1979, ISBN 978-0710000545).</ref> dealt with their own depression. | |

| − | '' | + | Social stigma of major depression continues to be widespread, and contact with mental health services reduces this only slightly. Public opinions on treatment differ markedly to those of health professionals; alternative treatments are held to be more helpful than pharmacological ones, which are viewed poorly.<ref>Gavin Andrews and Scott Henderson (eds.), ''Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0521027236).</ref> |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==References== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * American Psychiatric Association. ''Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5''. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2013. ISBN 978-0890425558 | |

| − | + | * Andrews, Gavin, and Scott Henderson (eds.). ''Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses''. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0521027236 | |

| − | + | * Barlow, David H., Vincent Mark Durand, and Stefan G. Hofmann. ''Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach (8th edition)''. Cengage Learning, 2017. ISBN 978-1305950443 | |

| − | '' | + | * Beck, Aaron T., A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery. ''Cognitive Therapy of Depression''. The Guilford Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0898629194 |

| − | + | * Blazer, Dan G. ''The Age of Melancholy: "Major Depression" and its Social Origin''. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0415951883 | |

| − | + | * Burlingame, Michael. ''The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln''. University of Illinois Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0252066672 | |

| − | + | * Cohen, David. ''J.B. Watson: The Founder of Behaviourism''. Routledge Kegan & Paul, 1979. ISBN 978-0710000545 | |

| − | + | * Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics of the American Psychiatric Association. ''Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-II''. American Psychiatric Association, 1968. {{ASIN|B0030A4JAE}} | |

| − | + | * Edel, Leon (ed.). ''The Letters of Henry James 1883–1895''. Belknap Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0674387829 | |

| − | + | * Eyers, Kerrie (ed.). ''Tracking the Black Dog''. University of New South Wales, 2006. ISBN 978-0868408125 | |

| − | + | * Freud, Sigmund. ''On Murder, Mourning, and Melancholia''. Penguin Classic, 2005. ISBN 978-0141183794 | |

| − | + | * Hallowell, Edward M., and John J. Ratey. ''Delivered from Distraction: Getting the Most out of Life with Attention Deficit Disorder''. Ballantine Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0345442314 | |

| − | + | * Hankin, Benjamin L., and John R.Z. Abela. ''Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective''. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2005. ISBN 1412904900 | |

| − | + | * Heffernan, Carol F. ''The Melancholy Muse: Chaucer, Shakespeare and Early Medicine''. Duquesne University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0820702629 | |

| − | + | * James, William. ''Letters of William James''. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2003. ISBN 978-0766175662 | |

| − | + | * Licinio, Julio, and Ma-Li Wong (eds.). ''Biology of Depression: From Novel Insights to Therapeutic Strategies''. Wiley-Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 3527307850 | |

| − | + | * Mill, John Stuart. ''Autobiography''. Adamant Media Corporation, 2000. ISBN 978-1421242002 | |

| − | + | * National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). ''Depression: The NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults''. RCPsych Publications, 2010. ISBN 978-1904671855 | |

| − | + | * Patton, Lauren L., and Michael Glick (eds.). ''The ADA Practical Guide to Patients with Medical Conditions 2nd Edition''. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. ISBN 978-1118924402 | |

| − | + | * Richards, C. Steven, and Michael W. O'Hara (eds.). ''The Oxford Handbook of Depression and Comorbidity''. Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0199797004 | |

| − | + | * Rosqvist, Johan, and Michel Hersen (eds.). ''Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Case Conceptualization, and Treatment, Volume 1: Adults''. Wiley, 2007. ISBN 978-0471779995 | |

| − | + | * Seymour, Miranda. ''Mary Shelley''. Grove Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0802139481 | |

| − | + | * Wolpert, Lewis. ''Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression''. Free Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0684870588 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * Beck, | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 7, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * [https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/expert-answers/clinical-depression/faq-20057770 Clinical depression: What does that mean?] ''Mayo Clinic'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.webmd.com/depression/guide/major-depression Major Depression (Clinical Depression)] ''WebMD'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression Depression] ''National Institute of Mental Health'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-clinical-depression-1067309 What Is Clinical Depression?] ''Very Well Mind'' | ||

| + | {{Credit|Major_depressive_disorder|1112057266}} | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Social sciences]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Psychology]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Health and disease]] | |

Latest revision as of 22:08, 7 January 2024

| Clinical depression | |

| |

| Other names | Major depressive disorder, major depression, unipolar depression, unipolar disorder, recurrent depression |

|---|---|

| Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate) by Vincent van Gogh (1890) | |

| Symptoms | Low mood, low self-esteem, loss of interest in normally enjoyable activities, low energy, pain without a clear cause[1] |

| Complications | Self-harm, suicide[2] |

| Usual onset | 20s[3] |

| Duration | > 2 weeks[1] |

| Causes | Environmental (adverse life experiences, stressful life events), genetic and psychological factors[3] |

| Risk factors | Family history, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, substance use disorder[1][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Bipolar disorder, ADHD, sadness[3] |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, antidepressant medication, electroconvulsive therapy, exercise[1] |

| Medication | Antidepressants |

Clinical Depression, also known as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), is a mental disorder characterized by pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities over a protracted period of time.

The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is based on the person's reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination. The course of the disorder varies widely, from one episode lasting months to a lifelong disorder with recurrent major depressive episodes. Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors. Risk factors include a family history of the condition, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, and substance use disorders. Those suffering from clinical depression are typically treated with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication.

Despite efforts to educate the public about mental disorders, social stigma continues to make it difficult both for those suffering from serious depression to admit their problems and for health professionals to diagnose and treat them. The view held by some psychiatrists that such depression is merely a social construct or imagined illness that is inappropriately regarded as an actual disease compounds these difficulties. Compassion as well as support for effective treatment is needed to allow those suffering from depression to receive appropriate and effective treatment so that they may be successful members of society.

Terminology

Clinical depression, also known as Major depressive disorder (MDD), is classified as a mental disorder. However, the term "depression" is used in a number of different ways. It is often used to mean the syndrome but may refer to other mood disorders or simply to a low mood. People's conceptualizations of depression vary widely: "Because of the lack of scientific certainty," one commentator has observed, "the debate over depression turns on questions of language. What we call it—'disease,' 'disorder,' 'state of mind'—affects how we view, diagnose, and treat it."[5]

History

The Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates described a syndrome of melancholia (μελαγχολία, melankholía) as a distinct disease with particular mental and physical symptoms; he characterized all "fears and despondencies, if they last a long time" as being symptomatic of the ailment.[6] It was a similar but far broader concept than today's depression; prominence was given to a clustering of the symptoms of sadness, dejection, and despondency, and often fear, anger, delusions, and obsessions were included.[7]

The term "depression" was derived from the Latin verb deprimere, meaning "to press down."[8] From the fourteenth century, "to depress" meant to subjugate or to bring down in spirits. It was used in 1665 in English author Richard Baker's Chronicle to refer to someone having "a great depression of spirit," and by English author Samuel Johnson in a similar sense in 1753.[9] An early usage referring to a psychiatric symptom was by French psychiatrist Louis Delasiauve in 1856, and by the 1860s it was appearing in medical dictionaries to refer to a physiological and metaphorical lowering of emotional function.[10] Since Aristotle, melancholia had been associated with men of learning and intellectual brilliance, a hazard of contemplation and creativity. The newer concept abandoned these associations and through the nineteenth century, and became more associated with women.[7]

Although "melancholia" remained the dominant diagnostic term, "depression" gained increasing currency in medical treatises and was a synonym by the end of the century; German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin may have been the first to use it as the overarching term, referring to different kinds of melancholia as "depressive states."[9] Freud likened the state of melancholia to mourning in his 1917 paper Mourning and Melancholia. He theorized that objective loss, such as the loss of a valued relationship through death or a romantic break-up, results in subjective loss as well; the depressed individual has identified with the object of affection through an unconscious, narcissistic process called the "libidinal cathexis" of the ego. Such loss results in severe melancholic symptoms more profound than mourning; not only is the outside world viewed negatively but the ego itself is compromised.[11] He also emphasized early life experiences as a predisposing factor.[7] Adolf Meyer put forward a mixed social and biological framework emphasizing reactions in the context of an individual's life, and argued that the term "depression" should be used instead of "melancholia."[12]

The first version of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) published in 1952, contained "depressive reaction" and the DSM-II, published in 1968, contained "depressive neurosis." These were defined as an excessive reaction to internal conflict or an identifiable event, and also included a depressive type of manic-depressive psychosis within the area of "Major affective disorders."[13]

The term "Major Depressive Disorder was introduced by a group of US clinicians in the mid-1970s as part of proposals for diagnostic criteria based on patterns of symptoms (called the "Research Diagnostic Criteria," building on the earlier Feighner Criteria).[14] The American Psychiatric Association added "major depressive disorder" to the DSM-III, published in 1980, as a split of the previous depressive neurosis in the DSM-II, which also encompassed the conditions now known as dysthymia (or Persistent Depressive Disorder or PDD) and adjustment disorder with depressed mood.[15]

To maintain consistency, the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) used the same criteria, with only minor alterations. It used the DSM diagnostic threshold to mark a "mild depressive episode," adding higher threshold categories for moderate and severe episodes.[16] The ancient idea of "melancholia: still survives in the notion of a melancholic subtype.

Symptoms

Major depression significantly affects a person's family and personal relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health.[17] A person having a major depressive episode usually exhibits a low mood, which pervades all aspects of life, and an inability to experience pleasure in previously enjoyable activities. They may be preoccupied with—or ruminate over—thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, inappropriate guilt or regret, helplessness or hopelessness.[3]

Other symptoms of depression include poor concentration and memory, withdrawal from social situations and activities, reduced sex drive, irritability, and thoughts of death or suicide. Insomnia is common; in the typical pattern, a person wakes very early and cannot get back to sleep. Hypersomnia, or oversleeping, can also happen. In severe cases, depressed people may have psychotic symptoms. These symptoms include delusions or, less commonly, hallucinations, usually unpleasant.[3]

A depressed person may report multiple physical symptoms such as fatigue, headaches, or digestive problems. Appetite often decreases, resulting in weight loss, although increased appetite and weight gain occasionally occur. Family and friends may notice agitation or lethargy. Elderly people may not present with classical depressive symptoms; they may have cognitive symptoms of recent onset, such as forgetfulness, and a more noticeable slowing of movements. Depressed children may often display an irritable rather than a depressed mood; most lose interest in school and show a steep decline in academic performance.[3]

Causes

Major depressive disorder is believed to be caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors: In other words, biological, psychological, and social factors all play a role in causing depression. Risk factors include a family history of the condition, major life changes, certain medications, chronic health problems, and substance use disorders.[1][3]

The diathesis–stress model specifies that depression results when a preexisting vulnerability, or diathesis, is activated by stressful life events. The preexisting vulnerability can be either genetic, implying an interaction between nature and nurture, or schematic, resulting from views of the world learned in childhood.[19]

American psychiatrist Aaron Beck suggested that a triad of automatic and spontaneous negative thoughts about the self, the world or environment, and the future may lead to other depressive signs and symptoms.[20]

Adverse childhood experiences (incorporating childhood abuse, neglect and family dysfunction) markedly increase the risk of major depression.[3] Childhood trauma also correlates with severity of depression, poor responsiveness to treatment, and length of illness.

There has been a continuing discussion of whether neurological disorders and mood disorders may be linked to creativity, a discussion that goes back to Aristotelian times.[21] British literature gives many examples of reflections on depression.[22] English philosopher John Stuart Mill experienced a several-months-long period of what he called "a dull state of nerves," when one is "unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent." He quoted English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Dejection" as a perfect description of his case: "A grief without a pang, void, dark and drear, / A drowsy, stifled, unimpassioned grief, / Which finds no natural outlet or relief / In word, or sigh, or tear."[23] English writer Samuel Johnson used the term "the black dog" in the 1780s to describe his own depression, and it was subsequently popularized by British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill, who also had the disorder.[24]

Depression can also come secondary to a chronic or terminal medical condition, such as HIV/AIDS or asthma, and may be labeled "secondary depression."[25] It is unknown whether the underlying diseases induce depression through effect on quality of life, or through shared etiologies (such as degeneration of the basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease or immune dysregulation in asthma). Depression may also be iatrogenic (the result of healthcare), such as depression as a side effect of prescribed medications. Depression occurring after giving birth, postpartum depression, is thought to be the result of hormonal changes associated with pregnancy. Seasonal affective disorder is a type of depression associated with seasonal changes in sunlight where people who have normal mental health throughout most of the year exhibit depressive symptoms at the same time each year, most often in winter.

Diagnosis

There is no laboratory test for clinical depression, and so diagnosis is based on the person's reported experiences, behavior reported by relatives or friends, and a mental status examination, although tests may be conducted to rule out physical conditions that can cause similar symptoms.[26]

Clinical assessment

A diagnostic assessment may be conducted by a suitably trained general practitioner, or by a psychiatrist or psychologist, who records the person's current circumstances, biographical history, current symptoms, family history, and alcohol and drug use. The assessment also includes a mental state examination, which is an assessment of the person's current mood and thought content, in particular the presence of themes of hopelessness or pessimism, self-harm or suicide, and an absence of positive thoughts or plans.[17]

Rating scales are not used to diagnose depression, but they provide an indication of the severity of symptoms for a time period, so a person who scores above a given cut-off point can be more thoroughly evaluated for a depressive disorder diagnosis. Several rating scales are used for this purpose, including the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.

Specialist mental health services are rare in rural areas, especially in developing countries, and thus diagnosis and management is left largely to primary-care clinicians. Since primary-care physicians have more difficulty with under-recognition and under-treatment of depression compared to psychiatrists, they often miss cases where people experience physical symptoms accompanying their depression.

A doctor generally performs a medical examination and selected investigations to rule out other causes of depressive symptoms. These can include blood tests to exclude hypothyroidism and metabolic disturbance, or a systemic infection or chronic disease.Testosterone levels may be evaluated to diagnose hypogonadism, a cause of depression in men. Adverse affective reactions to medications or alcohol misuse may be ruled out, as well. Subjective cognitive complaints appear in older depressed people, but they can also be indicative of the onset of a dementing disorder, such as Alzheimer's disease, which can be rule out through Cognitive testing and brain imaging.

DSM and ICD criteria

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing depressive conditions are found in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). The latter system is typically used in European countries, while the former is used in the US and many other non-European nations, and the authors of both have worked towards conforming one with the other. Both DSM and ICD mark out typical (main) depressive symptoms.[16]

- ICD-11

Under mood disorders, ICD-11 classifies major depressive disorder as either "single episode depressive disorder" (where there is no history of depressive episodes, or of mania)[27] or "recurrent depressive disorder" (where there is a history of prior episodes, with no history of mania).[28] These two disorders are classified as "Depressive disorders," in the category of "Mood disorders". The symptoms, which must affect work, social, or domestic activities and be present nearly every day for at least two weeks, are a depressed mood or anhedonia, accompanied by other symptoms such as "difficulty concentrating, feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, hopelessness, recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, changes in appetite or sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, and reduced energy or fatigue."[27][28] The ICD-11 system allows further specifiers for the current depressive episode: the severity (mild, moderate, severe, unspecified); the presence of psychotic symptoms (with or without psychotic symptoms); and the degree of remission if relevant (currently in partial remission, currently in full remission).[27][28]

- DSM-5

Major depressive disorder is classified as a mood disorder in DSM-5. There are two main depressive symptoms: a depressed mood, and loss of interest/pleasure in activities (anhedonia). These symptoms, as well as five out of the nine more specific symptoms listed, must frequently occur for more than two weeks (to the extent in which they impair functioning) for the diagnosis. Further qualifiers are used to classify both the episode itself and the course of the disorder. The category Unspecified Depressive Disorder is diagnosed if the depressive episode's manifestation does not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[3]

A major depressive episode is characterized by the presence of a severely depressed mood that persists for at least two weeks. Episodes may be isolated or recurrent and are categorized as mild (few symptoms in excess of minimum criteria), moderate, or severe (marked impact on social or occupational functioning). An episode with psychotic features—commonly referred to as "psychotic depression"—is automatically rated as severe. If the person has had an episode of mania or markedly elevated mood, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is made instead.

Bereavement is not an exclusion criterion in DSM-5, and it is up to the clinician to distinguish between normal reactions to a loss and MDD. Excluded are a range of related diagnoses, including dysthymia, which involves a chronic but milder mood disturbance; recurrent brief depression, consisting of briefer depressive episodes; minor depressive disorder, whereby only some symptoms of major depression are present; and adjustment disorder with depressed mood, which denotes low mood resulting from a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor.[3]

The DSM-5 recognizes six further subtypes of MDD, called "specifiers," in addition to noting the length, severity, and presence of psychotic features:[3]

- "Melancholic depression" is characterized by a loss of pleasure in most or all activities, a failure of reactivity to pleasurable stimuli, a quality of depressed mood more pronounced than that of grief or loss, a worsening of symptoms in the morning hours, early-morning waking, psychomotor retardation, excessive weight loss (not to be confused with anorexia nervosa), or excessive guilt.

- "Atypical depression" is characterized by mood reactivity (paradoxical anhedonia) and positivity, significant weight gain or increased appetite (comfort eating), excessive sleep or sleepiness (hypersomnia), a sensation of heaviness in limbs known as leaden paralysis, and significant long-term social impairment as a consequence of hypersensitivity to perceived interpersonal rejection.

- "Catatonic depression" is a rare and severe form of major depression involving disturbances of motor behavior and other symptoms. Here, the person is mute and almost stuporous, and either remains immobile or exhibits purposeless or even bizarre movements. Catatonic symptoms also occur in schizophrenia or in manic episodes, or may be caused by neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

- "Depression with anxious distress" was added into the DSM-5 as a means to emphasize the common co-occurrence between depression or mania and anxiety, as well as the risk of suicide of depressed individuals with anxiety.

- "Depression with peri-partum onset" refers to the intense, sustained, and sometimes disabling depression experienced by women after giving birth or while a woman is pregnant. To qualify as depression with peripartum onset, onset must occur during pregnancy or within one month of delivery.

- "Seasonal affective disorder" (SAD) is a form of depression in which depressive episodes come on in the autumn or winter, and resolve in spring. The diagnosis is made if at least two episodes have occurred in colder months with none at other times, over a two-year period or longer.

Differential diagnoses

Other disorders need to be ruled out before diagnosing major depressive disorder. They include depressions due to physical illness, medications, and substance use disorders. Depression due to physical illness is diagnosed as a mood disorder due to a general medical condition. This condition is determined based on history, laboratory findings, or physical examination. When the depression is caused by a medication, non-medical use of a psychoactive substance, or exposure to a toxin, it is then diagnosed as a specific mood disorder (previously called substance-induced mood disorder).[3]

To confirm major depressive disorder as the most likely diagnosis, other potential diagnoses must be considered, including dysthymia, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, or bipolar disorder. Dysthymia is a chronic, milder mood disturbance in which a person reports a low mood almost daily over a span of at least two years. The symptoms are not as severe as those for major depression. Adjustment disorder with depressed mood is a mood disturbance appearing as a psychological response to an identifiable event or stressor, in which the resulting emotional or behavioral symptoms are significant but do not meet the criteria for a major depressive episode.[3]

Cultural differences

There are cultural differences in the extent to which serious depression is considered an illness requiring personal professional treatment, or an indicator of something else, such as the need to address social or moral problems, the result of biological imbalances, or a reflection of individual differences in the understanding of distress that may reinforce feelings of powerlessness, and emotional struggle.[29]

A diagnosis of illness is less common in some countries, such as China. It has been suggested that the Chinese traditionally deny or somatize emotional depression. Alternatively, it may be that Western cultures reframe and elevate some expressions of human distress to disorder status. Australian professor Gordon Parker and others have argued that the Western concept of depression medicalizes sadness or misery.[30] Similarly, Hungarian-American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz and others argue that depression is a metaphorical illness that is inappropriately regarded as an actual disease,[31] or that there is a failure to take into consideration the influence of social constructs.[32]

Management

The pathophysiology of depression is not completely understood. The most common and effective treatments are psychotherapy, medication, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); a combination of treatments being the most effective approach.

American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines recommend that initial treatment should be individually tailored based on factors including severity of symptoms, co-existing disorders, prior treatment experience, and personal preference. Options may include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, exercise, ECT, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), or light therapy. Antidepressant medication is recommended as an initial treatment choice in people with mild, moderate, or severe major depression, and should be given to all people with severe depression unless ECT is planned.[33]

Talk therapies

Talk therapy, or psychotherapy can be delivered to individuals, groups, or families by mental health professionals, including psychotherapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, clinical social workers, counselors, and psychiatric nurses. With more complex and chronic forms of depression, a combination of medication and psychotherapy may be used.