Difference between revisions of "Bela Bartok" - New World Encyclopedia

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) (import, credit, version number) |

Dave Eaton (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

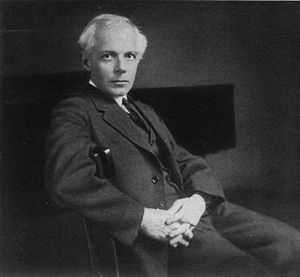

'''Béla Viktor János Bartók''' ({{IPA2|ˈbeːlɒ ˈbɒrtoːk}}; [[March 25]], [[1881]] – [[September 26]], [[1945]]) was a [[Hungary|Hungarian]] [[composer]], [[pianist]] and collector of Eastern [[Europe]]an and [[Middle East]]ern [[folk music]]. Bartók is considered one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the field of [[ethnomusicology]], the anthropology or ethnography of music. | '''Béla Viktor János Bartók''' ({{IPA2|ˈbeːlɒ ˈbɒrtoːk}}; [[March 25]], [[1881]] – [[September 26]], [[1945]]) was a [[Hungary|Hungarian]] [[composer]], [[pianist]] and collector of Eastern [[Europe]]an and [[Middle East]]ern [[folk music]]. Bartók is considered one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the field of [[ethnomusicology]], the anthropology or ethnography of music. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His pioneering efforts in the field of [[ethnomusicology]] with his colleague, composer [[Zoltan Kodaly]], contributed to the interest in collecting, studying and documenting folk music of indigenous cultures. This aspect of his musical life was as important as his composing. It was through his efforts in the area of [[ethnomusicology]] that a greater appeciation of music of other cultures would inevitably lead to the breaking down of cultural barriers and in so doing, provide a greater understanding of "the other." | ||

==Childhood and early years== | ==Childhood and early years== | ||

Revision as of 17:43, 22 November 2006

- "Bartok" redirects here.

Béla Viktor János Bartók (IPA: [ˈbeːlɒ ˈbɒrtoːk]; March 25, 1881 – September 26, 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and collector of Eastern European and Middle Eastern folk music. Bartók is considered one of the greatest composers of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the field of ethnomusicology, the anthropology or ethnography of music.

His pioneering efforts in the field of ethnomusicology with his colleague, composer Zoltan Kodaly, contributed to the interest in collecting, studying and documenting folk music of indigenous cultures. This aspect of his musical life was as important as his composing. It was through his efforts in the area of ethnomusicology that a greater appeciation of music of other cultures would inevitably lead to the breaking down of cultural barriers and in so doing, provide a greater understanding of "the other."

Childhood and early years

Bartók was born in the Transylvanian town Nagyszentmiklós (now Sânnicolau Mare, Romania), in the Greater Hungary, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire which was partitioned by the Treaty of Trianon after World War I.

He learned to play the piano early: by the age of four he was able to play 40 songs, and his mother began teaching him at the age of five.

After his father, the director of an agricultural school, died in 1888, Béla's mother, Paula, took her family to live in Nagyszőlős (today Vinogradiv, Ukraine), and then to Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia). When Czechoslovakia was created in 1918 Béla and his mother found themselves on opposite sides of the border.

Early musical career

He later studied piano under István Thoman and composition under János Koessler at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest from 1899 to 1903. There he met Zoltán Kodály and together they collected folk music from the region. This was to have a major impact on his style. Previously, Bartók's idea of Hungarian folk music was derived from the gypsy melodies to be found in the works of Franz Liszt. In 1903, Bartók wrote a large orchestral work, Kossuth, which honored Lajos Kossuth, hero of the Hungarian revolution of 1848 and incorporated gypsy melodies.

Emergence and influences on Bartók's music

Upon discovering Magyar peasant folk song (which he regarded as true Hungarian folk music, as opposed to the gypsy music used by Liszt) Bartók began to incorporate folk songs into his own compositions and write original folk-like tunes, as well as frequently using folksy rhythmic figures.

It was the music of Richard Strauss, whom he met at the Budapest premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra in 1902, that had most influence. This new style emerged over the next few years. Bartók was building a career for himself as a pianist when, in 1907, he landed a job as piano professor at the Royal Academy. This allowed him to stay in Hungary rather than having to tour Europe as a pianist, and also allowed him to collect more folk songs, notably in Transylvania. Meanwhile his music was beginning to be influenced by this activity and by the music of Claude Debussy that Kodály had brought back from Paris. His large scale orchestral works were still in the manner of Johannes Brahms or Richard Strauss, but he wrote a number of small piano pieces which show his growing interest in folk music. Probably the first piece to show clear signs of this new interest is the String Quartet No. 1 (1908), which has several folk-like elements in it.

Middle years and career

In 1909, Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son, Béla Jr., was born in 1910.

In 1911, Bartók wrote what was to be his only opera, Bluebeard's Castle, dedicated to his wife, Márta. He entered it for a prize awarded by the Hungarian Fine Arts Commission, but they said it was unplayable, and rejected it out of hand. The opera remained unperformed until 1918, when Bartók was pressured by the government to remove the name of the librettist, Béla Balázs, from the program on account of his political views. Bartók refused, and eventually withdrew the work. For the remainder of his life, Bartók did not feel greatly attached to the government or institutions of Hungary, although his love affair with its folk music continued.

After his disappointment over the Fine Arts Commission prize, Bartók wrote very little for two or three years, preferring to concentrate on folk music collecting and arranging (in Central Europe, the Balkans, Algeria, and Turkey). However, the outbreak of World War I forced him to stop these expeditions, and he returned to composing, writing the ballet The Wooden Prince in 1914–16 and the String Quartet No. 2 in 1915–17. It was The Wooden Prince which gave him some degree of international fame.

He subsequently worked on another ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin, influenced by Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, as well as Richard Strauss, following this up with his two violin sonatas which are harmonically and structurally some of the most complex pieces he wrote. He wrote his third and fourth string quartets in 1927–28, after which he gradually simplified his harmonic language. The String Quartet No. 5 (1934) is somewhat more traditional from this point of view. Bartók wrote his sixth and last string quartet in 1939.

The Miraculous Mandarin was started in 1918, but not performed until 1926 because of its sexual content, a sordid modern story of prostitution, robbery, and murder.

Bartók divorced Márta in 1923, and married a piano student, Ditta Pásztory. His second son, Péter, was born in 1924. For Péter's music lessons Bartók began composing a six-volume collection of graded piano pieces, Mikrokosmos, which remains popular with piano students today.

World War II and later career

In 1940, after the outbreak of World War II, and the European political situation worsened, Bartók was increasingly tempted to flee Hungary.

Bartók was strongly opposed to the Nazis. After they came into power in Germany, he refused to concertize there and switched away from his German publisher. His liberal views (as evident in the opera Bluebeard's Castle and the ballet The Miraculous Mandarin) caused him a great deal of trouble from right-wingers in Hungary.

Having first sent his manuscripts out of the country, Bartók reluctantly moved to the USA with Ditta Pásztory. Péter Bartók joined them in 1942 and later enlisted in the United States Navy. Béla Bartók, Jr. remained in Hungary.

Bartók did not feel comfortable in the USA, and found it very difficult to write. As well, he was not very well known in America and there was little interest in his music. He and his wife Ditta would give concerts; and for a while, they had a research grant to work on a collection of Yugoslav folk songs, but their finances were precarious, as was Bartók's health.

His last work might well have been the String Quartet No. 6, were it not for Serge Koussevitsky commissioning him to write the Concerto for Orchestra, at the behest of the violinist Joseph Szigeti and the conductor Fritz Reiner (who had been Bartók's friend and champion since his days as Bartók's student at the Royal Academy). This quickly became Bartók's most popular work and which was to ease his financial burdens. He was also commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin to write Sonata for Solo Violin. This seemed to reawaken his interest in composing, and he went on to write his Piano Concerto No. 3, an airy and almost neo-classical work, and begin work on his Viola Concerto.

Béla Bartók died in New York City from leukemia in September, 1945. He left the viola concerto unfinished at his death; it was later completed by his pupil, Tibor Serly.

He was interred in the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York, but after the fall of Hungarian communism in 1988, his remains were transferred to Budapest, Hungary for a state funeral on July 7, 1988 with interment in Budapest's Farkasreti Cemetery.

There is a statue of Béla Bartók in Brussels, Belgium near the central train station in a public square, Place d'Espagne, and another in London, opposite South Kensington Underground Station.

Music

Paul Wilson lists as the most prominent characteristics of Bartók's music the influence of the folk music of rural Hungary and eastern Europe and the art music of central and western Europe, and his changing attitude toward (and use of) tonality, but without the use of the traditional harmonic functions associated with major and minor scales (Wilson 1992, p.2-4).

Bartók is an influential modernist (though see Reception below) and his music used or may be analysed as containing various modernist techniques such as atonality, bitonality, attenuated harmonic function, polymodal chromaticism, projected sets, privileged patterns, and large set types used as source sets such as the equal tempered twelve tone aggregate, octatonic scale (and alpha chord), the diatonic and heptatonia seconda seven-note scales, and less often the whole tone scale and the primary pentatonic collection (ibid, p.24-29).

He rarely used the aggregate actively to shape musical structure, though there are notable examples such as the second theme from the first movement of his Second Violin Concerto, commenting that he "wanted to show Schoenberg that one can use all twelve tones and still remain tonal". More thoroughly, in the first eight measures of the last movement of his Second Quartet, all notes gradually gather with the twelfth (G♭) sounding for the first time on the last beat of measure 8, marking the end of the first section. The aggregate is partitioned in the opening of the Third String Quartet with C♯-D-D♯-E in the accompaniment (strings) while the remaining pitch classes are used in the melody (violin 1) and more often as 7-35 (diatonic or "white-key" collection) and 5-35 (pentatonic or "black-key" collection) such as in no. 6 of the Eight Improvisations. There, the primary theme is on the black keys in the left hand, while the right accompanies with triads from the white keys. In measures 50-51 in the third movement of the Fourth Quartet, the first violin and 'cello play black-key chords, while the second violin and viola play stepwise diatonic lines (ibid, p.25).

Ernő Lendvai (1971) analyses Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden section and the acoustic scale, and tonally on the axis system (ibid, p.7).

Reception

Some of Bartók's works have been criticized for their use of tonality and nontonal methods unique to each piece; Milton Babbitt, for example, praises the "identification of the personal exigency with the fundamental musical exigency of the epoch" yet concludes that "Bartók's solution was a specific one, it cannot be duplicated." The problem is Bartók's praised use of "two organizational principles" - tonality for large scale relationships and the piece-specific method for moment to moment thematic elements - worrying that the "highly attenuated tonality" requires extreme non-harmonic methods to create a feeling of closure. Presumably he preferred Arnold Schoenberg's completely non-tonal non-piece specific method of twelve tone music. (Maus 2004, p.164)

Selected works

Works are catalogued with the designation Sz (Szöllösy).

Stage Works

- Duke Bluebeard's Castle, opera

- The Miraculous Mandarin, ballet-pantomime

- The Wooden Prince, ballet

Orchestral Works

- Dance Suite (1923)

- Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1937)

- Concerto for Orchestra (1942–43, revised 1945)

Concertante Works

- Piano

- Piano Concerto No. 1 (1926)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 (1932)

- Piano Concerto No. 3 (1945)

- Violin

- Violin Concerto No. 1 (1907-1908, 1st pub 1956)

- Violin Concerto No. 2 (1937-38)

- Rhapsody No. 1 for Violin and Orchestra (1928–29)

- Rhapsody No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra (1928, rev. 1935)

- Viola

- Viola Concerto (1945)

Choral Works

- Cantata Profana (1930)

- From Olden Times (1935)

Chamber Works

- Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion

- String Quartets Nos. 1-6

- Contrasts for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano (1938)

- Violin Sonata Nos. 1-3

- Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939)

- Violin duets (44 Duos)

Piano Works

- Two Romanian Folk Dances (1910)

- Allegro barbaro (1911)

- Elegy Op. 8a, 8b (191?)

- Bagatellen (1911)

- Piano Sonatina (1915)

- Romanian Folk Dances (1915) These were also arranged for piano and violin as well as an orchestral version

- Suite for Piano, Op. 14 (1916)

- Improvisations Op. 20 (1920)

- Piano Sonata (1926)

- Im Freien (Out of Doors) (1926)

- Mikrokosmos - These include the 6 Dances in Bulgarian Rhythym dedicated to Miss Harriet Cohen (1926, 1932–39)

Arrangements by others

- Suite paysanne hongroise (arranged by Paul Alma, for flute and piano or orchestra)

See also

- Category:Compositions by Béla Bartók

Sources

- Maus, Fred (2004). "Sexual and Musical Categories", The Pleasure of Modernist Music. ISBN 1580461433.

- Wilson, Paul (1992). The Music of Béla Bartók. ISBN 0300051115.

- Gillies, Malcolm. "Béla Bartók", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed May 23, 2006), (subscription access)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Antokoletz, Elliott (1984). The Music of Béla Bartók: A Study of Tonality and Progression in Twentieth-Century Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Kárpáti, János (1975). Bartók's String Quartets. Translated by Fred MacNicol. Budapest: Corvina Press.

- Lendvai, Ernő (1971). Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn and Averill.

External links

- Bartók Béla Memorial House, Budapest

- A chronological list of Bartók's compositions

- IMSLP - International Music Score Library Project's Bartók page.

- Recording Contrasts: Verbunkos - Helen Kim, violin; Ted Gurch, clarinet; Adam Bowles, piano Luna Nova New Music Ensemble

- Recording Contrasts: Pinheno - Helen Kim, violin; Ted Gurch, clarinet; Adam Bowles, piano Luna Nova New Music Ensemble

- Recording Contrasts: Sebes - Helen Kim, violin; Ted Gurch, clarinet; Adam Bowles, piano Luna Nova New Music Ensemble

- Classical Cat page of Bartók links

- His biography at Hungary.hu

- Bartók and his relationship with Unitarianism

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.