Battle of France

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

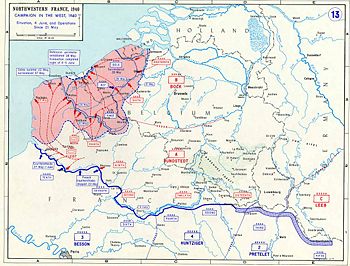

In World War II, the Battle of France, also known as the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, executed from 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), German armored units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and surround the Allied units that had advanced into Belgium. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and many French soldiers were however evacuated from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo. In the second operation, Fall Rot (Case Red), executed from 5 June, German forces outflanked the Maginot Line to attack the larger territory of France. Italy declared war on France on 10 June. The French government fled to Bordeaux, and Paris was occupied on 14 June. After the French Second Army Group surrendered on 22 June, France capitulated on 25 June. For the Axis, the campaign was a spectacular victory.[4]

France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north and west, a small Italian occupation zone in the southeast and a collaborationist rump state in the south, Vichy France. Southern France was occupied on 10 November 1942 and France remained under German occupation until after the Allied landings in 1944; the Low Countries were liberated in 1944 and 1945.

Prelude

Following the Invasion of Poland of September 1939 that started the Second World War, a period of inaction called the Phoney War ("Sitzkrieg" or "Drôle de guerre") set in between the major powers. Hitler had hoped that France and the United Kingdom would acquiesce in his conquest and quickly make peace. This was essential to him because Germany's stock of raw materials—and of the foreign currencies to buy them—was critically low. He was now dependent on supplies from the Soviet Union, a situation that made him uncomfortable for ideological reasons. On 6 October he made a peace offer to both Western Powers. Even before they had time to respond to it, on 9 October he also formulated a new military policy in case their reply was negative: the Führer-Anweisung N°6, or "Führer-Directive Number 6."

German strategy

Hitler had always fostered dreams about major military campaigns to defeat the Western European nations as a preliminary step to the conquest of territory in the East, thus avoiding a two-front war. However, these intentions were absent from the Führer-Directive N°6. This plan was firmly based on the seemingly more realistic assumption that Germany's military strength would still have to be built up for several more years and that for the moment only limited objectives could be envisaged, aimed at improving Germany's position to survive a long, protracted war in the West.[5] Hitler ordered a conquest of the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg) to be executed at the shortest possible notice. This would prevent France from occupying them first, which would threaten the vital German Ruhr Area. It would also provide a basis for a successful long-term air and sea campaign against the United Kingdom. There was no mention in the Führer-Directive of any immediately consecutive attack to conquer the whole of France, although as much as possible of the border areas in northern France should be occupied.

While writing the directive, Hitler had assumed that such an attack could be initiated within a period of at most a few weeks, but the very day he issued it he was disabused of this illusion. Hitler had been misinformed about the true state of Germany's forces. The motorized units had to recover for an estimated three months, repairing the damage to their vehicles incurred in the Polish campaign; the ammunition stocks were largely depleted.[6]

Halder's plan

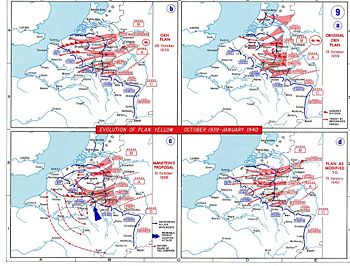

On 10 October 1939, the British refused Hitler's offer of peace; on 12 October the French did the same. On 19 October Franz Halder, the chief of staff of the OKH, the German Army High Command, presented the first plan for Fall Gelb ("Case Yellow"), the pre-war codename of plans for campaigns in the Low Countries: the Aufmarschanweisung N°1, Fall Gelb, or "Deployment Instruction No. 1, Case Yellow." Halder's plan has often been compared to Schlieffen Plan, which the Germans carried out in 1914 during World War I. Both plans entailed an advance through the middle of Belgium, but while the intention of the Schlieffen Plan was to gain a decisive victory by executing a surprising gigantic encirclement of the French army, Aufmarschanweisung N°1 was based on an unimaginative frontal attack, sacrificing a projected half a million German soldiers to attain the limited goal of throwing the Allies back to the River Somme. Germany's strength for 1940 would then be spent; only in 1942 could the main attack against France begin.[7]

Hitler was very disappointed by Halder's plan. He had supposed the conquest of the Low Countries could be quick and cheap, but as it was presented, it would be long and difficult. It has even been suggested that Halder, who was at the time conspiring against Hitler and had begun carrying a revolver to shoot him in person if necessary, proposed the most pessimistic plan possible to discourage Hitler from the attack entirely.[8] Hitler reacted in two ways. He decided that the German army should attack early, ready or not, in the hope that Allied unpreparedness might bring about an easy victory. He set the date for 12 November 1939. This led to an endless series of postponements, as time and again commanders managed to convince Hitler that the attack should be further delayed for a few days or weeks to remedy some critical defect in the preparations, or to wait for better weather conditions. Secondly, because the plan did not appeal to him, Hitler tried to improve the plan without clearly understanding how it could be improved. This mainly resulted in a dispersion of effort, since besides the main axis in central Belgium, secondary attacks were foreseen further south. On 29 October, Halder let a second operational plan, Aufmarschanweisung N°2, Fall Gelb, reflect these changes by featuring a secondary attack on the Liège-Namur axis.

Hitler was not alone in disliking Halder's plan. General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group A, also disagreed with it. Unlike Hitler however, von Rundstedt, as a professional soldier, understood perfectly how it should be rectified. Its fundamental flaw was that it did not conform to the classic principles of the Bewegungskrieg, the "manoeuvre warfare," that had been the basis of German tactics since the 19th century. A breakthrough would have to be accomplished that would result in the encirclement and destruction of the main body of Allied forces. The logical place to achieve this would be the Sedan axis, which lay in the sector of von Rundstedt's Army Group A. On 21 October, von Rundstedt agreed with his chief of staff, Lieutenant-General Erich von Manstein, that an alternative operational plan had to be arranged that would reflect these basic ideas, making his Army Group A as strong as possible at the expense of Army Group B to the north.

Manstein Plan

While von Manstein was formulating the new plans in Koblenz, it so happened that Lieutenant-General Heinz Guderian, commander of the XIXth Army Corps, Germany's elite armoured formation, was lodged in a nearby hotel.[9] Von Manstein now considered that, should he involve Guderian in his planning, the tank general may come up with some role for his Army Corps to play in it, and this might then be used as a decisive argument to relocate XIXth Army Corps from Army Group B to Army Group A, much to the delight of von Rundstedt. At this moment von Manstein's plan consisted in a move from Sedan to the north, right in the rear of the main Allied forces, to engage them directly from the south in full battle. When Guderian was invited to contribute to the plan during informal discussions, he proposed a radical and novel idea. Not only his army corps, but the entire Panzerwaffe should be concentrated at Sedan. This concentration of armor should subsequently not move to the north but to the west, to execute a swift, deep, independent strategic penetration towards the English Channel without waiting for the main body of infantry divisions. This could lead to a strategic collapse of the enemy, avoiding the relatively high number of casualties normally caused by a classic Kesselschlacht or "annihilation battle." Such a risky independent strategic use of armor had been widely discussed in Germany before the war but had not at all been accepted as received doctrine; the large number of officers serving in the Infantry, which was the dominant Arm of Service, had successfully prevented this. Von Manstein had to admit that in this special case, however, it might be just the thing needed. His main objection was that it would create an open flank of over 300 kilometers, vulnerable to French counterattack. Guderian convinced him that this could be prevented by launching simultaneous spoiling attacks to the south by small armoured units. However, this would be a departure from the basic concept of the Führer-Directive N°6.

Von Manstein wrote his first memorandum outlining the alternative plan on 31 October. In it he carefully avoided mentioning Guderian's name and downplayed the strategic part of the armored units, in order not to generate unnecessary resistance.[10] Six more memoranda followed between 6 November 1939 and 12 January 1940, slowly growing more radical in outline. All were rejected by the OKH and nothing of their content reached Hitler.

Plan revisions

On 10 January 1940, a German Messerschmitt Bf 108 made a forced landing at Maasmechelen, north of Maastricht, in Belgium (the so-called "Mechelen Incident"). Among the occupants of the aircraft was a Luftwaffe major, Hellmuth Reinberger, who was carrying a copy of the latest version of Aufmarschanweisung N°2. Reinberger was unable to destroy the documents, which quickly fell into the hands of the Belgian intelligence services.[11] It has often been suggested this incident was the cause of a drastic change in German plans, but this is incorrect; in fact a reformulation of them on 30 January, Aufmarschanweisung N°3, Fall Gelb, basically conformed to the earlier versions.[12] On 27 January, von Manstein was relieved of his appointment as Chief of Staff of Army Group A and appointed commander of an army corps in Prussia, to begin his command in Stettin on 9 February. This move was instigated by Halder to remove von Manstein from influence. Von Manstein's indignant staff then brought his case to the attention of Hitler, who was informed of it on 2 February. Von Manstein was invited to explain his proposal to the Führer personally in Berlin on 17 February. Hitler was much impressed by it, and the next day he ordered the plans to be changed in accordance with von Manstein's ideas. They appealed to Hitler mainly because they at last offered some real hope of a cheap victory.

The man who had to carry out the change was again Franz Halder–von Manstein was not further involved. Halder consented to shifting the main effort, the Schwerpunkt, to the south. Von Manstein's plan had the virtue of being unlikely (from a defensive point of view) since the Ardennes were heavily wooded and because of their poor road network, they were implausible as a route for an invasion. An element of surprise would therefore be present. It would be essential that the Allies respond as envisaged in the original plans, namely that the main body of French and British elite troops be drawn north to defend Belgium. To help to ensure this condition, the German Army Group B had to execute a holding attack in Belgium and the Netherlands, giving the impression of being the main German effort, in order to draw Allied forces eastward into the developing encirclement and hold them there. To accomplish this, three of the ten available armoured divisions were still allocated to Army Group B.

However, Halder had no intention of deviating from established doctrine by allowing an independent strategic penetration by the seven armoured divisions of Army Group A.[13] Much to the outrage of Guderian, this element was at first completely removed from the new plan, Aufmarschanweisung N°4, Fall Gelb, issued on 24 February. The crossings of the River Meuse at Sedan should be forced by infantry divisions on the eighth day of the invasion. Only after much debate was this changed to allow the motorised infantry regiments of the armoured divisions to establish bridgeheads on the fourth day, to gain four days. Even now the breakout and drive to the English Channel would start only on the ninth day, after a delay of five days during which a sufficient number of infantry divisions had to be built up in order to advance together with the armoured units in a coherent mass.

Even when adapted to more conventional methods, the new strategy provoked a storm of protest from the majority of German generals. They thought it utterly irresponsible to create a concentration of forces in a position where they could not possibly be sufficiently supplied, while such inadequate supply routes as there were could easily be cut off by the French. If the Allies did not react as expected the German offensive could end in catastrophe.[14] Their objections were ignored however. Halder argued that, as Germany's strategic position seemed hopeless anyway, even the slightest chance of a decisive victory outweighed the certainty of ultimate defeat implied by inaction.[15] The adaptation also implied that it would be easier for the Allied forces to escape to the south. Halder pointed out that if so, Germany's victory would be even cheaper, while it would be an enormous blow to the reputation of the Entente (as the Anglo-French alliance was still commonly known in 1940) to have abandoned the Low Countries. Moreover Germany's fighting power would then still be intact, so that it might be possible to execute Fall Rot, the main attack on France, immediately afterwards. However, a decision to this effect would have to be postponed until after a possible successful completion of Fall Gelb. Indeed German detailed operational planning only covered the first nine days; there was no fixed timetable established for the advance to the Channel. In accordance with the tradition of the Auftragstaktik, much would be left to the judgment and initiative of the field commanders. This indetermination would have an enormous effect on the actual course of events.

In April 1940, for strategic reasons, the Germans launched Operation Weserübung, an attack on the neutral countries of Denmark and Norway. The British, French, and Free Poles responded with an Allied campaign in Norway in support of the Norwegians.

Allied strategy

In September 1939, Belgium and the Netherlands were still neutral. They tried to stay out of the war for as long as possible by adhering to a policy of strict neutrality. Though they made arrangements in secret with the Entente for future cooperation should the Germans invade their territory, they did not openly prepare for this. The Supreme Commander of the French Army, Maurice Gamelin, suggested during that month that the Allies should take advantage of the fact that Germany was tied up in Poland by occupying the Low Countries before Germany could. This suggestion was not taken up by the French government, however.

In September 1939, in the token Saar Offensive—only made to nominally fulfill the prewar guarantee to Poland to execute a relief attack from the West—French soldiers advanced 5 kilometers into the Saar before withdrawing in October. At this time, France had deployed 98 divisions (all but 28 of them reserve or fortress divisions) and 2,500 tanks against German forces consisting of 43 divisions (32 of them reserve divisions) and no tanks. According to the judgment of Wilhelm Keitel, then Chief OKW, the French army would easily have been able to penetrate the mere screen of German forces present.[16]

After October, it was decided not to take the initiative in 1940, though important parts of the French army in the 1930s had been designed to wage offensive warfare. The Allies believed that even without an Eastern Front the German government might be destabilized by a blockade, as it had been in the First World War. In the event the Nazi regime would not collapse, a possibility that seemed to grow ever more likely,[17] during 1940 a vast modernization and enlargement program for the Allied forces would be implemented, exploiting the existing advantages over Germany in war production to build up an overwhelming mechanized force, including about two dozen armored divisions, to execute a decisive offensive in the summer of 1941. Should the Low Countries by that date still not have committed themselves to the Allied cause, the Entente firmly intended to violate their neutrality if necessary.[18]

Obviously the Germans might strike first, and a strategy would have to be prepared for this eventuality. Neither the French nor the British had anticipated such a rapid defeat in Poland, and the quick German victory there was disturbing. Most French generals favored a very cautious approach. They thought it wise not to presume that the German intentions could be correctly predicted. A large force should be held in reserve in a central position, north of Paris, to be prepared for any contingency. Should the Germans indeed take the obvious route of advance through Flanders, they should only be engaged in northern France, when their infantry would be exhausted and they had run out of supplies. If however they would try an attack on the centre of the Allied front, this Allied reserve would be ideally positioned to block it. If the Germans advanced through Switzerland, a large reserve would be the only means to deal with such a surprise.

Dyle Plan

Gamelin rejected this line of thought, for several reasons. The first was that it was politically unthinkable to abandon the Low Countries to their fate, however prudent it might be from an operational point of view. Certainly the British government insisted that the Flemish coast remain under Allied control. The second reason was that the 1941 offensive had no chance of being decisive if it had to be launched from the north of France against German forces entrenched in central Belgium. The German offensive had to be contained as far east as possible. The last and for him personally most cogent argument was that Gamelin did not consider the French army capable of winning a mobile battle with the German army. The French infantry divisions as yet were insufficiently motorised. The events in Poland helped confirm his opinion. Such a confrontation had to be avoided at all cost, and Gamelin intended to send the best units of the French army along with the British Expeditionary Force north to halt the Germans at the KW-line, a defensive line that followed the river Dyle, east of Brussels, in a coherent tightly packed continuous front uniting the British, Belgian, and French armies. This plan thus presumed that the Germans planned to concentrate their forces where they could be well supplied by the better road network of northern Belgium. [citation needed]

Gamelin however did not have the personal influence to simply impose his will. The first step he took was to propose the "Escaut" variant as an option for Plan D (the codename for an advance into the Low Countries). It was named after the river in Flanders. Protecting the Flemish coast seemed the least one could do; on the other hand it created an enormous salient, showing that it made more sense to defend along the shorter Dyle line, which was precisely the content of Gamelin's next proposal in November, after he had become confident the Belgians would be able to delay the Germans sufficiently. This however was too transparent. His second "Dyle Plan" met with strong opposition, not growing any less when the Mechelen crash on 10 January 1940 confirmed that the German plans conformed to Gamelin's expectations. Also, General Lord Gort, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, was beginning to expect that whatever the Germans came up with instead would not be what he had initially predicted. The main objection was that the manoeuvre was very risky. The Allied forces had to complete their advance and entrenchment before the Germans reached the Dyle line, for which there seemed to be barely enough time. When entrenched they would have trouble reacting to German strategic surprises, also because their fuel supplies would have to be replenished. The next problem was that this line was very vulnerable to the German main strength, their large tactical bomber force. Nothing seemed to prevent them from breaking the line by a massive bombardment, forcing the French Army into an encounter battle after all. [citation needed]

Gamelin successfully countered these arguments by adopting the seemingly reasonable assumption that the Germans would try to attempt a breakthrough by concentrating their mechanised forces. They could hardly hope to break the Maginot Line on his right flank or to overcome the Allied concentration of forces on the left flank. That only left the centre, but most of the centre was covered by the river Meuse. Tanks were useless in defeating fortified river positions. However, at Namur the river made a sharp turn to the east, creating a gap between itself and the river Dyle. This Gembloux Gap, ideal for mechanised warfare, was a very dangerous weak spot. Gamelin decided to concentrate half of his armoured reserves there. By thus assuming that the decisive moment in the campaign would take the form of a gigantic tank battle, he avoided the problem of the German tactical bomber force since air attacks were considered less effective against mobile armoured units, the tanks of which would be hard to hit. Of course the Germans might try to overcome the Meuse position by using infantry, but that could only be achieved by massive artillery support, the gradual build-up of which would give Gamelin ample warning to allow him to reinforce the Meuse line. [citation needed]

During the first months of 1940 the size and readiness of the French army steadily grew, and Gamelin began to feel confident enough to propose a somewhat more ambitious strategy. He had no intention of frontally attacking the German fortification zone, the Westwall, in 1941, planning instead to outflank it from the north, just as four years later Bernard Montgomery intended in Operation Market Garden. To achieve this, it would be most convenient if he already had a foothold on the north bank of the Rhine, so he changed his plans to the effect that a French army should maintain a connection north of Antwerp with the Dutch National Redoubt, "Fortress Holland." He assigned his sole strategic reserve, the French Seventh Army, to this task. His only reserves now consisted of individual divisions. Again there was much opposition to this "Dyle-Breda-Plan" within the French army, but Gamelin was strongly supported by the British government, because Holland proper was an ideal base for a German air campaign against England. [citation needed]

Forces and dispositions

Germany

Germany deployed about three million men for the battle. Because from 1919 no conscription had been allowed by the Treaty of Versailles, a provision which the German government had repudiated as recently as 1935, in May 1940 only 79 divisions out of a total of 157 raised had completed their training; another fourteen were nevertheless directly committed to battle, mainly in Army Group C and against the Netherlands. Beside this total of 93 front-line divisions (ten armored, six motorized) there were also 39 OKH reserve divisions in the West, about a third of which would not be committed to battle. About a quarter of the combat troops consisted of veterans from the First World War, older than forty.

The German forces in the West would in May and June deploy some 2,700 tanks and self-propelled guns, including matériel reserves committed; about 7,500 artillery pieces were available with ammunition stocks sufficient for six weeks of fighting. The Luftwaffe divided its forces into two groups. 1,815 combat, 487 Transport and 50 Glider aircraft were deployed to support Army Group B, while a further 3,286 combat aircraft were deployed to support Army Group A and C.[19]

The German Army was divided into three army groups:

- Army Group A commanded by Gerd von Rundstedt, composed of 45½ divisions including seven armored, was to execute the decisive movement, cutting a "Sichelschnitt"—not the official name of the operation but the translation in German of a phrase after the events coined by Winston Churchill[20] as "Sickle Cut" (and even earlier "armored scythe stroke"[21])—through the Allied defenses in the Ardennes. It consisted of three armies: the Fourth, Twelfth and Sixteenth. It had three Panzer corps; one, XV Army Corps, had been allocated to the Fourth Army, but the other two (XXXXI Army Corps including the 2nd Motorized Infantry Division and XIX Army Corps) were united with XIV Army Corps of two motorized infantry divisions, on a special independent operational level in Panzergruppe Kleist. This was done to better coordinate the approach march to the Meuse river; once bridgeheads had been established across the river, the Panzer Group headquarters would be disbanded and its three corps would be divided between Twelfth and Sixteenth Army.

- Army Group B under Fedor von Bock, composed of 29½ divisions including three armored, was tasked with advancing through the Low Countries and luring the northern units of the Allied armies into a pocket. It consisted of the Eighteenth and Sixth Army.

- Army Group C, composed of 18 divisions under Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, was charged with preventing a flanking movement from the east, and with launching small holding attacks against the Maginot Line and the upper Rhine. It consisted of the First and Seventh Army.

Allies

Because of a low birthrate, which had even further declined during the First World War, France had a severe manpower shortage relative to its total population, which furthermore was barely half that of Germany. To compensate, France had mobilized about a third of the male population between the ages of 20 and 45, bringing the strength of its armed forces to over six million men, more than the entire German Wehrmacht of 5.4 million. Only 2.2 million of these served in army units in the north, though the total there was brought to over 3.3 million by the British, Belgian and Dutch forces. On 10 May there were 93 French, 22 Belgian, 10 British and nine Dutch divisions in the North, for a total of 134. Six of these were armored divisions, 24 motorized divisions. Twenty-two more divisions were being trained or assembled on an emergency basis during the campaign (not counting the reconstituted units), among which were two Polish and one Czech division. Beside full divisions the Allies had many independent smaller infantry units: the Dutch had the equivalent of about eight divisions in independent brigades and battalions; the French had 29 independent Fortress Infantry Regiments. Of the French divisions eighteen were manned by colonial volunteer troops; nineteen consisted of "B-divisions," once fully trained units that however had a large number of men over thirty and needed retraining after mobilization. The best trained Allied forces were the British divisions, fully motorised and having a large percentage of professional soldiers; the worst the very poorly equipped Dutch troops.

The Allied forces deployed an organic strength of about 3,100 modern tanks and self-propelled guns on 10 May; another 1,200 were committed to battle in new units or from the matériel reserves; also 1,500 obsolete FT-17 tanks were sent to the front for a total of about 5,800. They had about 14,000 pieces of artillery. The Allies thus enjoyed a clear numerical superiority on the ground[22] but were inferior in the air: the French Armee de l'Air had 1,562 aircraft, and RAF Fighter Command committed 680 machines, while Bomber Command could contribute some 392 aircraft to operations.[23] Most of the Allied aircraft were obsolete types; among the fighter force only the British Hawker Hurricane and the French Dewoitine D.520 could contend with the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 on something approaching equal terms.[24]

At the beginning of Fall Rot, French aviation industry had reached a considerable output, and estimated the matériel reserve at nearly 2,000. However, a chronic lack of spare parts crippled this stocked fleet. Only 29% (599) of the aircraft were serviceable, of which 170 were bombers.[25]

The French forces in the north had three Army Groups: the Second and the Third defended the Maginot Line in the east; the First Army Group under Gaston-Henri Billotte was situated in the west and would execute the movement forward into the Low Countries. At the coast was the French Seventh Army, reinforced by a Light Mechanized (armored) division (DLM). The Seventh Army was intended to move to the Netherlands via Antwerp. Next to the south were the nine divisions of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which would advance to the Dyle Line and position itself to the right of the Belgian army. The French First Army, reinforced by two Light Mechanized Divisions, with a Reserve Armored Division (DCR) in reserve, would defend the Gembloux Gap. The southernmost army involved in the move forward into Belgium was the French Ninth Army, which had to cover the entire Meuse sector between Namur and Sedan. At Sedan, the French Second Army would form the "hinge" of the movement and remain entrenched.

The First Army Group had 35 French divisions; the total of 40 divisions of the other Allies in its sector brought their forces equal in number to the combined German forces of Army Group A and B. However, the former only had to confront the 18 divisions of the Ninth and Second Armies, and thus would have a large local superiority. To reinforce a threatened sector Gamelin had sixteen strategic reserve divisions available on General Headquarters level, two of them armored. These were "reserve" divisions in the operational sense only, in fact consisting of high quality troops — most of them had been active divisions in peace time, and were thus not comparable to the German reserve divisions that were half-trained. Confusingly, all mobilised French divisions were officially classified as A or B "reserve divisions," although most of them served directly in the front armies.

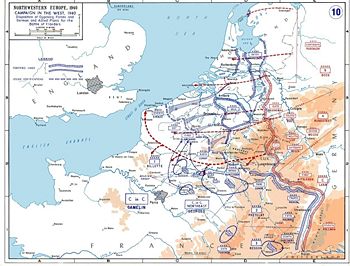

May: Fall Gelb, Low Countries and northern France

The North

Germany initiated Fall Gelb on the evening prior to and the night of 10 May. During the late evening of 9 May, German forces occupied Luxembourg.[26] In the night Army Group B launched its feint offensive into the Netherlands and Belgium. Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) from the 7th Flieger and 22. Luftlande Infanterie-Division under Kurt Student executed that morning surprise landings at The Hague, on the road to Rotterdam and against the Belgian Fort Eben-Emael in order to facilitate Army Group B's advance.

The French command reacted immediately, sending its First Army Group north in accordance with Plan D. This move committed their best forces, diminished their fighting power through loss of readiness and their mobility through loss of fuel. That evening the French Seventh Army crossed the Dutch border, only to find the Dutch already in full retreat. The French and British air command was less effective than their generals had anticipated, and the Luftwaffe quickly obtained air superiority, depriving the Allies of key reconnaissance abilities and disrupting Allied communication and coordination.

Netherlands

The Luftwaffe was guaranteed air superiority over the Netherlands. The Dutch Air Force, the Militaire Luchtvaartafdeling (ML), had a strength of 144 combat aircraft, half of which were destroyed within the first day of operations.[27] The remainder was dispersed and accounted for only a handful of Luftwaffe aircraft shot down. In total the ML flew a mere 332 sorties losing 110 of its aircraft.[28]

The German 18th Army secured all the strategically vital bridges in and toward Rotterdam, which penetrated Fortress Holland and bypassed the New Water Line from the south. However, an operation organized separately by the Luftwaffe to seize the Dutch seat of government, known as the Battle for The Hague, ended in complete failure. The airfields surrounding the city (Ypenburg, Ockenburg, and Valkenburg) were taken with heavy casualties and transport aircraft losses, only to be lost that same day to counterattacks by the two Dutch reserve infantry divisions. The Dutch captured or killed 1,745 Fallschirmjäger, shipping 1,200 prisoners to England.

The Luftwaffe's Transportgruppen also suffered heavily. Transporting the German paratroops had cost it 125 Ju 52 destroyed and 47 damaged, representing 50 percent of the fleet's strength[29] Most of these transports were destroyed on the ground, and some while trying to land under fire, as German forces had not properly secured the airfields and landing zones.

The French Seventh Army failed to block the German armoured reinforcements from the 9th Panzer Division, which they reached Rotterdam on 13 May. That same day in the east, following the Battle of the Grebbeberg in which a Dutch counter-offensive to contain a German breach had failed, the Dutch retreated from the Grebbe line to the New Water Line.

The Dutch Army, still largely intact, surrendered in the evening of 14 May after the Bombing of Rotterdam by Heinkel He 111s of Kampfgeschwader 54. It considered its strategic situation to have become hopeless and feared further destruction of the major Dutch cities. The capitulation document was signed on 15 May. However, the Dutch troops in Zeeland and the colonies continued the fight while Queen Wilhelmina established a government-in-exile in Britain.

Central Belgium

The Germans were able to establish air superiority in Belgium with ease. Having completed thorough photographic reconnaissance missions, they destroyed 83 of the 179 aircraft of the Aeronautique Militaire within the first 24 hours. The Belgians would fly on 77 operational missions but would contribute little to the air campaign. The Luftwaffe was assured air superiority over the Low Countries.[30]

Because Army Group B had been so weakened compared to the earlier plans, the feint offensive by German Sixth Army was in danger of stalling immediately, since the Belgian defences on the Albert Canal position were very strong. The main approach route was blocked by Fort Eben-Emael, a large fortress then generally considered the most modern in the world, controlling the junction of the Meuse and the Albert Canal. Any delay might endanger the outcome of the entire campaign, because it was essential that the main body of Allied troops was engaged before Army Group A would establish bridgeheads.

To overcome this difficulty, the Germans resorted to unconventional means in the Battle of Fort Eben-Emael. In the early hours of 10 May gliders landed on the roof of Fort Eben-Emael unloading assault teams that disabled the main gun cupolas with hollow charges. The bridges over the canal were seized by German paratroopers. Shocked by a breach in its defences just where they had seemed the strongest, the Belgian Supreme Command withdrew its divisions to the KW-line five days earlier than planned. At that moment however the BEF and the French First Army were not yet entrenched. When Erich Hoepner's XVI Panzer Corps, consisting of 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions was launched over the over the newly-captured bridges in the direction of the Gembloux Gap, this seemed to confirm the expectations of the French Supreme Command that the German Schwerpunkt would be at that point. The two French Light Mechanized divisions, the 2nd DLM and 3rd DLM were ordered forward to meet the German armor and cover the entrenchment of the First Army. The resulting Battle of Hannut, which took place on 12 May and 13 May was the largest tank battle until that date, with about 1,500 AFVs participating. The French claimed to have disable about 160 German tanks[31] for 91 Hotchkiss H35 and 30 Somua S35 tanks destroyed or captured.[32] However, as the Germans controlled the battlefield area afterwards, they recovered and eventually repaired or rebuilt many of the Panzers:[33] German irreparable losses amounted to 49 tanks (20 3PD and 29 4PD).[34] The German armour sustained substantial breakdown rates making it impossible to ascertain the exact number of tanks disabled by French action. On the second day the Germans managed to breach the screen of French tanks, which were successfully withdrawn on 14 May after having gained enough time for the First Army to dig in. Hoepner tried to break the French line on 15 May against orders, the only time in the campaign when German armour frontally attacked a strongly held fortified position. The attempt was repelled by the 1st Moroccan Infantry Division, costing 4th Panzer Division another 42 tanks, 26 of which were irreparable.[35][36]. This defensive success for the French was however already made irrelevant by the events further south.

The Center

In the center, the progress of German Army Group A was to be delayed by Belgian motorized infantry and French Mechanized Cavalry divisions (Divisions Légères de Cavalerie) advancing into the Ardennes. These forces however had an insufficient anti-tank capacity to block the surprisingly large number of German tanks they encountered and quickly gave way, withdrawing behind the Meuse. The German advance was however greatly hampered by the sheer number of troops trying to force their way through the poor road network. Kleist's Panzer Group had more than 41,000 vehicles.[37] To traverse the Ardennes Mountains, this huge armada of vehicles had been granted only four march routes.[38] The time-tables proved to have been wildly optimistic and soon a traffic congestion formed, beginning well over the Rhine to the east, that would last for almost two weeks. This made Army Group A very vulnerable to French air attacks, but these did not materialize.[39]

Although Gamelin was well aware of the situation, the French tactical bomber force was far too weak to challenge German air superiority so close to the German border. However, on 11 May Gamelin ordered many reserve divisions to begin reinforcing the Meuse sector. Because of the danger the Luftwaffe posed, movement over the rail network was limited to the night, slowing the reinforcement, but the French felt no sense of urgency as the build-up of German divisions would be accordingly slow.

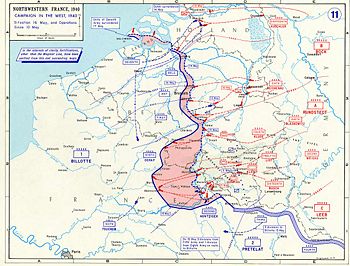

The German advance forces reached the Meuse line late in the afternoon of 12 May. To allow each of the three armies of Army Group A to cross, three major bridgeheads were to be established: at Sedan in the south, at Monthermé twenty kilometers to the northwest and at Dinant, another fifty kilometers to the north. The first units to arrive had hardly even a local numerical superiority; their already insufficient artillery support was further limited by an average supply of just twelve rounds apiece.[40]

Sedan

At Sedan the Meuse Line consisted of a strong defensive belt, constructed six kilometers deep according to the modern principles of zone defense on slopes overlooking the Meuse valley and strengthened by 103 pillboxes, manned by 147th Fortress Infantry Regiment. The deeper positions were held by the 55th Infantry Division (55e DI). This was only a grade “B” reserve division, but already reinforcements were arriving; in the morning of 13 May, 71e DI was inserted to the east of Sedan, allowing 55e DI to narrow its front by a third and deepen its position to over ten kilometres. Furthermore it had a superiority in artillery to the German units present on 13 May.[41] The French command fully expected that the Germans would only attack such formidable defences when a large infantry and artillery force had been built up, a concentration that apparently could not be completed before 20 May, given the traffic congestion; a date very similar to Halder's original projection. It thus came as a complete surprise when crossing attempts were made as early as the fourth day of the invasion.

On 13 May, the German XIX Army Corps forced three crossings near Sedan, executed by the motorized infantry regiments of 1st, 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions, reinforced by the elite Großdeutschland infantry regiment. Instead of slowly massing artillery as the French expected, the Germans concentrated most of their tactical bomber force to punch a hole in a narrow sector of the French lines by carpet bombing punctuated by dive bombing. Hermann Göring had promised Guderian that there would be an extraordinary heavy air support of a continual eight hour air attack, from 8am until dusk.[42] Luftflotte 3, supported by Luftflotte 2, executed the heaviest air bombardment the world had yet witnessed and the most intense by the Luftwaffe during the war. .[43] The Luftwaffe committed two Stukageschwader to the assault flying 300 sorties against French positions, with Stukageschwader 77 alone flying 201 individual missions.[44] By the nine Kampfgeschwader (medium bomber units - See Luftwaffe Organization) committed, a total of 3,940 sorties were flown, often in Gruppe strength.[45]

The forward platoons and pillboxes of the 147 RIF were little affected by the bombardment and held their positions throughout most of the day, initially repulsing the crossing attempts of 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions on their left and right. However, there was a gap in the line of bunkers in the center of the river bend. In the late afternoon Großdeutschland penetrated this position, trying to quickly exploit this opportunity. The deep French zone defense had been devised to defeat just this kind of infiltration tactics; it now transpired however that the morale of the deeper company positions of the 55e DI had been broken by the impact of the German air attacks. They had been routed or were too dazed to offer effective resistance any longer. The French supporting artillery batteries had fled, and this created an impression among the remaining main defense line troops of the 55e DI that they were isolated and abandoned. They too went into rout by the late evening. At a cost of a few hundred casualties[46] the German infantry had penetrated up to 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) into the French defence zone by midnight. Even then, most of the infantry had not crossed yet, much of the success being from the actions of just six platoons, mainly assault engineers.[47]

The disorder that had begun at Sedan was spread down the French lines by groups of haggard and retreating soldiers. At 19:00hrs on 13 May, the 295th regiment of 55e DI, holding the last prepared defence line at the Bulson ridge, 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) from the Meuse, was panicked by the false rumor that German tanks were already behind its positions. It fled, creating a gap in the French defenses, before even a single German tank had crossed the river. This "Panic of Bulson," or phénomène d’hallucination collective involved the divisional artillery, so that the crossing sites were no longer within range of the French batteries. The division dissolved and ceased to exist. The Germans had not attacked their position, and would not do so until 12 hours later.[48]

In the morning of 14 May, two French FCM 36 tank battalions (4 and 7 BCC) and the reserve regiment of 55e DI, 213rd RI, executed a counterattack on the German bridgehead. It was repulsed at Bulson by the first German armor and anti-tank units which had been rushed across the river from 07:20 on the first pontoon bridge.

General Gaston-Henri Billotte, commander of the First Army Group whose right flank pivoted on Sedan, urged the bridges across the Meuse River to be destroyed by air attack, convinced that "over them will pass either victory or defeat!"[49] That day every available Allied light bomber was employed in an attempt to destroy the three bridges, but failed to hit them while suffering heavy losses. The RAF Advanced Air Striking Force under the command of Air Vice-Marshal P H L Playfair, bore the brunt of the attacks. The plan called for the RAF to commit its bombers for the attack while they would receive protection from the French fighter groups. The British bombers received insufficient air cover and as a result some 21 French fighters and 48 British bombers, 44 percent of the A.A.S.F's strength, was destroyed by Oberst Gerd von Massow's Jagdfliegerführer 3 Jagdgruppen.[50] The French Armée de l'Air also tried to halt the German armored columns, but the small French bomber force had been so badly mauled the previous days, that only a couple dozen aircraft could be committed over that vital target [51]. Two French bombers were shot down.[52] The German anti-aircraft defences, consisting of one hundred and ninety eight 88 mm, fifty-four4 3.7 cm and eighty-one 20 mm cannon accounted for half of the Allied bombers destroyed.[53] In just one day the Allies lost ninety bombers. In the Luftwaffe it became known as the "Day of the Fighters".[54]

The commander of XIX Army Corps, Heinz Guderian, had indicated on 12 May that he wanted to enlarge the bridgehead to at least 20 kilometers (12 mi). His superior, Ewald von Kleist, however ordered him to limit it to a maximum of 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) before consolidation. On 14 May at 11:45, von Rundstedt confirmed this order,[55] which basically implied that the tanks should now start to dig in. Nevertheless Guderian immediately disobeyed, expanding the perimeter to the west and to the south.

In the original von Manstein Plan as Guderian had suggested it, secondary attacks would be carried out to the southeast, in the rear of the Maginot Line, to confuse the French command. This element had been removed by Halder but Guderian now sent 10th Panzer Division and Großdeutschland south to execute precisely such a feint attack,[56] using the only available route south over the Stonne plateau. However, the commander of the French Second Army, General Charles Huntzinger, intended to carry out a counterattack at the same spot by the armored 3e Division Cuirassée de Réserve (DCR) to eliminate the bridgehead. This resulted in an armored collision, both parties in vain trying to gain ground in furious attacks from 15 May to 18 May, the village of Stonne changing hands many times. Huntzinger considered this at least a defensive success and limited his efforts to protecting his flank. However, in the evening of 16 May, Guderian removed 10th Panzer Division from the effort, having found a better destination for it.

Guderian had turned his other two armored divisions, the 1st Panzer Division and 2nd Panzer Division sharply to the west on 14 May. In the afternoon of 14 May there was still a chance for the French to attack the exposed southern flank of 1st Panzer Division before 10th Panzer Division had entered the bridgehead, but it was thrown away when the planned attack by 3 DCR was delayed because it was not ready in time.[57]

On 15 May, in heavy fighting, Guderian's motorized infantry dispersed the reinforcements of the newly formed French Sixth Army in their assembly area west of Sedan, undercutting the southern flank of the French Ninth Army by 40 kilometers (25 mi) and forcing the 102nd Fortress Division to leave its positions that had blocked the tanks of XVI Army Corps at Monthermé. The French Second Army had been seriously mauled and had rendered itself impotent. While this was happening, the French Ninth Army began to disintegrate completely. This Army had already been reduced in size because some of its divisions were still in Belgium. They also did not have time to fortify and had been pushed back from the river by the unrelenting pressure of the attacking German infantry. This allowed the impetuous Erwin Rommel to break free with his 7th Panzer Division. Rommel had advanced quickly and his lines of communications with his superior, General Hermann Hoth and his Headquaters were cut. Using the Mission Command system to full effect, and not waiting for the French to establish a new line of defense, he continued to advance. The French 5th Motorized Infantry Division was sent to block him, but the Germans were advancing unexpectedly fast, and Rommel surprised the French vehicles while they were refueling on 15 May. The Germans were able to fire directly into the neatly lined French vehicles and overran their position completely. The French unit had "disintegrated into a wave of refugees; they had been overrun literally in their sleep".[58] By 17 May, Rommel had taken 10,000 prisoners and suffered only 36 losses.[59]

Blitzkrieg

According to the original plan of Halder, the Panzer Corps now had fulfilled a precisely circumscribed task. Their motorized infantry component had secured the river crossings and their tank regiments had conquered a dominant position. Now they had to consolidate, allowing the three dozen infantry divisions following them to position themselves for the real battle: perhaps a classic Kesselschlacht if the enemy should stay in the north or perhaps an encounter fight if he should try to escape to the south. In both cases an enormous mass of German divisions, both armored and infantry, would act in close cooperation to annihilate the enemy. The Panzer Corps was not to bring about the collapse of the enemy by themselves. The plan called for the Germans to build up forces for a period of about five days.

On 16 May however, both Guderian and Rommel disobeyed their explicit direct orders in an act of open insubordination against their superiors. They broke out of their bridgeheads and moved their divisions many kilometers to the west as fast as they could push them. Guderian reached Marle, eighty kilometers from Sedan, while Rommel crossed the river Sambre at Le Cateau, a hundred kilometers from his bridgehead at Dinant.

The interpretation of the actions of both generals has remained deeply controversial and is connected to the problem of the precise nature and origin of Blitzkrieg tactics, of which the 1940 campaign is often described as a classic example. An essential element of Blitzkrieg was considered to be a strategic envelopment executed by mechanized forces which led to the operational collapse of the defender. It has also been looked at as a novel, revolutionary, form of warfare. After the war, Guderian claimed to have acted on his own initiative, essentially inventing this classic form of Blitzkrieg on the spot. The traditional interpretation accepts the novel character of the Blitzkrieg tactic but considers Guderian's claim to be an empty boast, denying any fundamental divide within contemporaneous German operational doctrine, downplaying the internal German conflict as a mere difference of opinion about timing and pointing out that Guderian's claim is inconsistent with his professed rôle as the prophet of Blitzkrieg even before the war. It is seen as an anomaly that there is no explicit reference to such tactics in the German battle plans. A second, later, main interpretation also sees Blitzkrieg as revolutionary, but denies that it was in accordance with established doctrine, vindicating Guderian. In this view the Battle of France is the first historical instance of Blitzkrieg

While nobody knew the whereabouts of Rommel (he had advanced so quickly that he was out of range for radio contact, earning his 7th Panzer Division]] the nickname Gespenster-Division, "Ghost Division"), an enraged von Kleist flew to Guderian's position on the morning of 17 May and after a heated argument, relieved him of all duties. However, von Rundstedt refused to confirm the order.

Allied reaction

The Panzer Corps now slowed their advance considerably and had put themselves in a very vulnerable position. They were stretched out, exhausted, low on fuel, and many tanks had broken down. There was now a dangerous gap between them and the infantry. A determined attack by a fresh and large enough mechanized force could have cut the Panzers off and wiped them out.

The French High Command, however, was reeling from the shock of the sudden offensive and was now stung by a sense of defeatism. On the morning of 15 May French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud telephoned the new Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Winston Churchill and said "We have been defeated. We are beaten; we have lost the battle." Churchill, attempting to console Reynaud, reminded the Prime Minister of the all the times the Germans had broken through the Allied lines in World War I only to be stopped. However, Reynaud was inconsolable.

Churchill flew to Paris on 16 May. He immediately recognized the gravity of the situation when he observed that the French government was already burning its archives and was preparing for an evacuation of the capital. In a sombre meeting with the French commanders, Churchill asked General Gamelin, "Où est la masse de manoeuvre?" ["Where is the strategic reserve?"] that had saved Paris in the First World War. "Aucune" ["There is none,"] Gamelin replied. Later, Churchill described hearing this as the single most shocking moment in his life. Churchill asked Gamelin where and when the general proposed to launch a counterattack against the flanks of the German bulge. Gamelin simply replied "inferiority of numbers, inferiority of equipment, inferiority of methods".[60]

Gamelin was right. Most of the French reserve divisions had by now been committed. The only armoured division still in reserve, 2nd DCR, attacked on 16 May. However the French reserve armoured divisions, the Divisions Cuirassées de Réserve, were despite their name, very specialized breakthrough units, optimized for attacking fortified positions. They could be quite useful for defense, if dug in, but had very limited utility for an encounter fight. They could not execute combined infantry–tank tactics because they simply had no important motorized infantry component. They also suffered from poor tactical mobility because their heavy Char B1 bis tanks, in which half of the French tank budget had been invested, had to refuel twice a day. So the 2nd DCR was forced to divide themselves into a covering screen. The 2nd DCR's small subunits fought bravely but with little strategic effect.

Some of the best units in the north, however, had seen little fighting. Had they been kept in reserve they could have been used for a decisive counter strike. However, they had lost much of their fighting power by simply moving to the north and if they were forced to hurry south again it would cost them even more. The most powerful Allied division, the French 1st Light Mechanized Division, had been deployed near Dunkirk on 10 May. It had moved its forward units 220 kilometers (140 mi) to the northeast, beyond the Dutch city of 's-Hertogenbosch in just 32 hours. Upon finding that the Dutch army had already retreated to the north, they withdrew, and moved back to the south. When it reached the German lines again, only three of its 80 SOMUA S 35 tanks were operational, mostly as a result of breakdown.

Nevertheless, a radical decision to retreat to the south, while avoiding contact, could probably have saved most of the mechanized and motorized divisions, including the BEF. However, that would have meant leaving about thirty infantry divisions to their fate. The loss of Belgium alone would be seen as an enormous political blow. Besides, the Allies were uncertain about what the Germans would do next. They threatened in four directions: to the north, to attack the Allied main force directly; to the west, to cut it off; to the south, to occupy Paris and even to the east, to move behind the Maginot Line. The French response was to create a new reserve under General Touchon, among which was a reconstituted Seventh Army, using every unit they could safely pull out of the Maginot Line to block the way to Paris.

Colonel Charles de Gaulle, in command of France's hastily formed 4th DCR, attempted to launch an attack from the south which achieved a measure of success. This attack would later accord him considerable fame and a promotion to Brigadier General. However, de Gaulle's attacks on 17 May and 19 May did not significantly alter the overall situation.

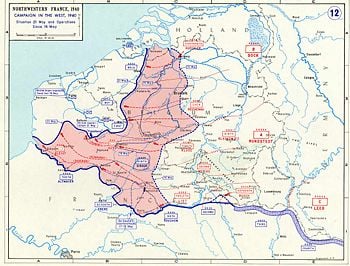

German advance to the Channel

The Allies did little either to threaten the Panzer Corps or escape from the danger they posed. So the Panzer troops used 17 May and 18 May to refuel, eat, sleep, and put more tanks in working order. On 18 May Rommel caused the French give up Cambrai by merely feinting an armoured attack toward the city.

The Allies seemed incapable of coping with events. On 19 May, General Ironside, the British Chief of the Imperial General Staff, conferred with General Gort, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, at his headquarters near Lens. Gort reported that the Commander of the French Northern Army Group, General Billotte, had given him no orders for eight days. Ironside confronted Billotte, whose own headquarters was nearby, and found him apparently incapable of taking decisive action.

Ironside had originally urged Gort to save the BEF by attacking south-west towards Amiens. Gort replied that seven of his nine divisions were already engaged on the Scheldt River, and he had only two divisions left with which he would be able to mount such an attack. Ironside returned to Britain concerned that the BEF was already doomed, and ordered urgent anti-invasion measures.

On that same day, the German High Command grew very confident. They determined that there appeared to be no serious threat to them from the south. In fact, General Franz Halder toyed with the idea of attacking Paris immediately to knock France out of the war with one blow. The Allied troops in the north were retreating to the river Scheldt which exposed their right flank to the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions. It would have been foolish for the Germans to remain inactive any longer since it would allow the Allies to reorganize their defense or escape. It was now time for the Germans to attempt to cut off the Allies' escape. The next day the Panzer Corps started moving again and smashed through the weak British 18th and 23rd Territorial Divisions. The Panzer Corps occupied Amiens and secured the westernmost bridge over the river Somme at Abbeville. This move isolated the British, French, Dutch, and Belgian forces in the north. That evening, a reconnaissance unit from 2nd Panzer Division reached Noyelles-sur-Mer, 100 kilometers (62 mi) to the west. From there they were able to see the estuary of the Somme flowing into the English Channel.

Fliegerkorps VIII under the command of Wolfram von Richthofen committed its StG 77 and StG 2 to covering this "dash to the channel coast." Heralded as the Stukas' "finest hour" these units responded via an extremely efficient communications system to the Panzer Divisions' every request for support, which effectively blasted a path for the Army. The Ju 87s were particularly effective at breaking up attacks along the flanks of the German forces, breaking fortified positions, and disrupting rear-area supply chains.[61] The Luftwaffe also benefitted from excellent ground-to-air communications throughout the campaign. Radio equipped forward liaison officers could call upon the Stukas and direct them to attack enemy positions along the axis of advance. In some cases the Stukas responded to requests in 10-20 minutes. Oberstleutnant Hans Seidmann (Richthofen's Chief of Staff) said that "never again was such a smoothly functioning system for discussing and planning joint operations achieved".[62]

Weygand Plan

On 20 May French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud dismissed Maurice Gamelin for his failure to contain the German offensive and replaced him with Maxime Weygand. Weygand immediately attempted to devise new tactics to contain the Germans. His strategic task was more pressing however, so he formulated what was to be known as the Weygand Plan. He ordered his forces to pinch off the German armoured spearhead by combining attacks from the north and the south. On the map this seemed like a feasible mission: the corridor through which von Kleist's two Panzer Corps had moved to the coast was a mere 40 kilometers (25 mi) wide. On paper Weygand had sufficient forces to execute it: in the north the three DLM and the BEF, in the south de Gaulle's 4th DCR. These units had an organic strength of about 1,200 tanks, and the Panzer divisions were again very vulnerable, due to the rapidly deteriorating mechanical condition of their tanks. However, the condition of the Allied divisions was far worse. Both in the south and the north they could in reality muster only a handful of tanks. Nevertheless Weygand flew to Ypres on 21 May trying to convince the Belgians and the BEF of the soundness of his plan.

That same day, a detachment of the British Expeditionary Force under Major-General Harold Edward Franklyn had already attempted to at least delay the German offensive and, perhaps, to cut off the leading edge of the German army. The resulting Battle of Arras demonstrated the ability of the heavily armoured British Matilda tanks (the German 37 mm anti-tank guns proved ineffective against them) and the limited raid overran two German regiments. The panic that resulted (the German commander at Arras, Erwin Rommel, reported being attacked by 'hundreds' of tanks, though there were only 74 (+60 French) at the battle) temporarily delayed the German offensive. Rommel was forced to rely on 88 mm anti-aircraft and 105 mm field guns firing over open sights to halt these attacks. German reinforcements were able to press the British back to Vimy Ridge the following day.

Although this attack was not part of any coordinated attempt to destroy the Panzer Corps, the German High Command panicked even more than Rommel did. For the moment they feared that they had been ambushed. They thought that hundreds of Allied tanks were about to smash into their elite forces.[63] However on the next day the German High Command had regained confidence and ordered Guderian's XIX Panzer Corps to press north and push into the Channel ports of Boulogne and Calais. This position was to the rear of the British and Allied forces to the north.

Also on 22 May, the French tried to attack south to the east of Arras with a measure of infantry and tanks. However, by now the German infantry had begun to catch up, and the attack was, with some difficulty, stopped by the German 32nd Infantry Division.

The first rather weak attack from the south was launched on 24 May when 7th DIC, supported by a handful of tanks, failed to retake Amiens. On 27 May the incomplete British 1st Armoured Division, which had been hastily brought forward from Evrecy in Normandy where it was forming, attacked Abbeville in force but was beaten back with crippling losses. The next day de Gaulle tried again but with the same result, but by now even a complete success might not have saved the Allied forces to the north.

BEF at Dunkirk

In the early hours of 23 May Gort ordered a retreat from Arras. By now he had no faith in the Weygand plan, nor in Weygand's proposal to at least try to hold a pocket on the Flemish coast, a so-called Réduit de Flandres. Gort knew that the ports needed to supply such a foothold were already being threatened. That same day the 2nd Panzer Division had assaulted Boulogne. The British garrison in Boulogne surrendered on 25 May, although 4,368 troops were evacuated. This British decision to withdraw was much criticised by later French publications.

The 10th Panzer Division attacked Calais, beginning on 24 May. British reinforcements (3rd Royal Tank Regiment, equipped with cruiser tanks, and the 30th Motor Brigade) had been hastily landed 24 hours before the Germans attacked. The Siege of Calais lasted for four days. The British defenders were finally overwhelmed and surrendered at approximately 16:00 on 26 May while the last French troops were evacuated in the early hours of 27 May.

The 1st Panzer Division was ready to attack Dunkirk on 25 May, but Hitler ordered it to halt the day before. This remains as one of the most controversial decisions of the entire war. Hermann Göring had convinced Hitler that the Luftwaffe could prevent an evacuation and von Rundstedt warned him that any further effort by the armoured divisions would lead to a much longer refitting period. Also attacking cities was not part of the normal task for armoured units under the German operational doctrine.

Encircled, the British, Belgian and French forces launched Operation Dynamo which evacuated Allied troops from the northern pocket in Belgium and Pas-de-Calais, beginning on 26 May. About 198,000 British soldiers were evacuated in Dynamo, along with nearly 140,000 French[64]; almost all of which later returned to France. The Allied position was complicated by Belgian King Léopold III's surrender the following day, which was postponed until 28 May.

During the Dunkirk battle the Luftwaffe flew 1,882 bombing and 1,997 fighter sweeps. British losses totalled 6% of their total losses during the French campaign, including 60 precious fighter pilots. However, the Luftwaffe failed in its task of preventing the evacuation, but had inflicted serious losses on the Allied forces. A total of 89 merchantmen (of 126,518 grt) were lost; the Royal Navy lost 29 of its 40 destroyers sunk or seriously damaged.[65]

As early on as the 16 May, the French position on the ground and in the air become desperate. They pressed the British to commit more of the RAF fighter groups to the battle. Hugh Dowding, C-in-C of RAF Fighter Command refused, arguing that if France collapsed, the British fighter force would be severely weakened. The RAF force of 1,078 had been reduced to just 475 aircraft. RAF records show just 179 Hawker Hurricanes and 205 Supermarine Spitfires were serviceable on 5 June 1940.[66]

Confusion still reigned. After the evacuation at Dunkirk and while Paris was enduring a short-lived siege, part of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division was sent to Brittany (Brest) and moved 320 kilometers (200 mi) inland toward Paris before they heard that Paris had fallen and France had capitulated. They retreated and re-embarked for England. Also the British 1st Armoured Division under General Evans (without its infantry, which had been re-assigned to keep the pressure off the BEF at Dunkirk) had arrived in France in June 1940 and was then joined by the former labour battalion of the 51st (Highland) Division and was forced to fight a rearguard action. Other British battalions were later landed at Cherbourg and were still waiting to form a second BEF.

At the end of the campaign Erwin Rommel praised the staunch resistance of British forces, despite being under-equipped and without ammunition for much of the fighting.[67]

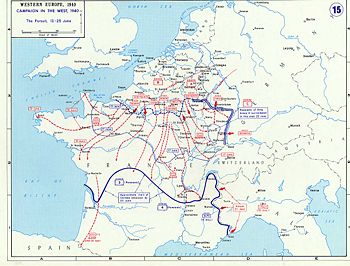

June: Fall Rot, France

French problems

The best and most modern French armies had been sent north and lost in the resulting encirclement; the French had lost much of their heavy weaponry and their best armored formations. Weygand was faced with the prospect of defending a long front (stretching from Sedan to the Channel), with a greatly depleted French Army now lacking significant Allied support. Sixty divisions were required to man the 600 kilometre (400 mi) long frontline, Weygand had only 64 French and one remaining British division (the 51st Highland Division) available. Therefore, unlike the Germans, he had no significant reserves to counter a breakthrough or to replace frontline troops, should they become exhausted from a prolonged battle. Should the frontline be pushed further south, it would inevitably get too long for the French to man it. Some elements of the French leadership had openly lost heart, particularly as the British were evacuating. The Dunkirk evacuation was a blow to French morale because it was seen as an act of abandonment.

Italy declares war

Adding to this grave situation, on 10 June, the Kingdom of Italy declared war on France and Britain. However, Italy was not prepared for war and made little impact during the last twelve days of fighting. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was aware of this and sought to profit from the successes of the Germans.[68] Mussolini felt the conflict would soon end. As he said to the Army's Chief-of-Staff, Marshal Badoglio:

- "I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought."[69]

Mussolini had the immediate war aim of expanding the Italian colonies in North Africa by taking land from the British and French colonies.

Of Italy's declaration of war, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, said:

- "On this tenth day of June 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor."[2]

New German offensive and the fall of Paris

The Germans renewed their offensive on 5 June on the Somme. An attack broke the scarce reserves that Weygand had put between the Germans and the capital, and on 10 June the French government fled to Bordeaux, declaring Paris an open city. Churchill returned to France on 11 June and met the French War Council in Briare. The French requested that Churchill supply all available fighter squadrons to aid in the battle. With only 25 squadrons remaining, Churchill refused, believing at this point that an upcoming Battle of Britain would be decisive in the war. At the meeting, Churchill obtained assurances from French admiral François Darlan that the fleet would not fall into German hands. On 14 June Paris, the capture of which had so eluded the German Army in World War I (see First Battle of the Marne), fell to the Wehrmacht. This marked the second time in a century that Paris had been captured by German forces (the former occurring during the 1870-1871 Franco-Prussian War).

German air supremacy

By this date the situation in the air had now grown critical. The Luftwaffe established air supremacy (as opposed to air superiority) as the French air arm was on the verge of collapse.[70] The French Air Force (Armee de l'Air) had only just begun to make the lion's share of bomber sorties, and between 5 June and 9 June, over 1,815 missions, of which 518 were bomber sorties, were flown. However, the number of sorties flown declined as losses were now becoming impossible to replace. The British Royal Air Force (RAF) attempted to divert the attention of the Luftwaffe with 660 sorties flown against targets over the Dunkirk area but losses were heavy; on 21 June alone 37 Bristol Blenheims were lost.[71] After 9 June, French aerial resistance virtually ceased and some surviving aircraft withdrew to French North Africa. The Luftwaffe now "ran riot." Its attacks were focused on direct and indirect support of the German Army (Wehrmacht Heer). The Luftwaffe subjected lines of resistance to ferocious assault, which then quickly collapsed under armoured attack.

The Luftwaffe virtually destroyed the Armée de l'Air during the campaign and inflicted heavy losses to the RAF contingent that was deployed. It is estimated the French lost 1,274 aircraft destroyed during the campaign, the British suffered losses of 959 (477 fighters).[72] The battle for France had cost the Luftwaffe 28% of its front line strength, some 1,428 aircraft destroyed. A further 488 were damaged, making a total of 36% of the Luftwaffe strength negatively affected.[73] The campaign had been a spectacular success for the German air-arm. The Luftwaffe had effectively destroyed three Allied air forces and inflicted heavy losses to a fourth.

Second BEF evacuation

Most of the remaining British troops in the field had arrived at Saint-Valery-en-Caux for evacuation, but the Germans took the heights around the harbour making this impossible and on June 12 General Fortune and the remaining British forces surrendered to Rommel. The evacuation of the second BEF took place during Operation Ariel between 15 June and 25 June. The Luftwaffe, with complete mastery of the French skies, was determined to prevent more Allied evacuations after the Dunkirk debacle. Fliegerkorps I was assigned to the Normandy and Brittany. On 9/10 June the port of Cherbourg was subject to 15 tonnes of German bombs, whilst Le Havre received 10 bombing attacks which sank 2,949 grt of escaping Allied shipping. On 17 June 1940 Junkers Ju 88s (mainly from Kampfgeschwader 30) destroyed a "10,000 tonne ship" which was the 16,243 grt Lancastria off St Nazaire killing some 5,800 Allied personnel[74]. Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe failed to prevent the mass evacuation of some 190 - 200,000 Allied personnel.

Surrender and Armistice

Prime Minister Paul Reynaud was forced to resign because he refused to agree to end the war. He was succeeded by Marshal Philippe Pétain, who delivered a radio address to the French people announcing his intention to ask for an armistice with Germany. When Hitler received word from the French government that they wished to negotiate an armistice, he selected the Compiègne Forest as the site for the negotiations. As Compiègne had been the site of the 1918 Armistice, which had ended World War I with a humiliating defeat for Germany, Hitler viewed the choice of location as a supreme moment of revenge for Germany over France. The armistice was signed on 22 June in the very same railway carriage in which the 1918 Armistice was signed (removed from a museum building and placed on the precise spot where it was located in 1918), Hitler sat in the same chair in which Marshal Ferdinand Foch had sat when he faced the defeated German representatives. After listening to the reading of the preamble, Hitler, in a calculated gesture of disdain to the French delegates, left the carriage, leaving the negotiations to his OKW Chief, General Wilhelm Keitel. The French Second Army Group, under the command of General Pretelat, surrendered the same day as the armistice and the cease-fire went into effect on 25 June 1940.

Aftermath

France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north and west and a nominally independent state in the south, to be based in the spa town of Vichy, dubbed Vichy France. The new French state, headed by Pétain, accepted its status as a defeated nation and attempted to buy favor with the Germans through accommodation and passivity. Charles de Gaulle, who had been made an Undersecretary of National Defense by Reynaud, in London at the time of the surrender, made his Appeal of 18 June. In this broadcast he refused to recognize the Vichy government as legitimate and began the task of organizing the Free French forces. Numerous French colonies abroad (French Guiana, French Equatorial Africa) joined de Gaulle rather than the Vichy government.

The British began to doubt Admiral Darlan's promise to Churchill not to allow the French fleet at Toulon to fall into German hands by the wording of the armistice conditions; they therefore attacked French naval forces in Africa and Europe, which led to feelings of animosity and mistrust between the former French and British allies.

Casualties

German

Approximately 27,074 Germans were killed and 111,034 were wounded, with a further 18,384 missing for total German casualties of 156,000 men.

Allied

In exchange, they had destroyed the French, Belgian, Dutch, Polish and British armies. Total Allied losses including the capture of the French army amounted to 2,292,000. Casualties, killed or wounded, were as follows:

- France - 90,000 killed, 200,000 wounded and approximately 1,800,000 captured. In August, 1940 1,575,000 prisoners were taken into Germany where roughly 940,000 remained until 1945 when they were liberated by advancing Allied forces. While in German captivity 24,600 French prisoners died, 71,000 escaped, 220,000 were released by various agreements between the Vichy government and Germany, and several hundred thousand were paroled because of disability and/or sickness.[75] Most prisoners spent their time in captivity as slave labourers.

- Britain - 68,111 killed, wounded or captured

- Belgium - 23,350 killed or wounded

- The Netherlands - 9,779 killed or wounded

- Poland - 6,092 killed, wounded or captured

- Czechoslovakia - 1,615 losses, including 400 killed.

Historiography

After the war the French Parliament instituted a Committee to investigate the causes of the defeat; its work unfinished, it was disbanded in 1951.[76] French interest in the events was afterwards rather limited with few major histories appearing.[77] This left the field to British and American writers. Three important works appeared in the 1960s: Guy Chapman's Why France Collapsed (1968); Alistair Horne's To Lose a Battle: France 1940 (1969) and William Shirer's The Collapse of the Third Republic: An Inquiry into the Fall of France in 1940 (1969).[78] The last two works, also translated into French, had a major influence on the public perception of the campaign.[79] They conformed to some earlier French works, as Marc Bloch's Étrange Défaite ("Strange Defeat," posthumously appearing in 1946) and Jacques Benoist-Méchin's Soixante jours qui ébranlèrent l'occident ("Sixty Days that shook the West," 1956) in describing France as a nation in moral crisis with a weak leadership and the people torn apart by political divisions. According to this view, strikes and budgetary limitations had prevented an adequate preparation for war. France, terminally in decline, had become defeatist and defensive and this was reflected in the attitude of a "sclerotic" High Command, unable to adapt itself to modern tactics. This situation is then contrasted to that in Germany, where the assumed acceptance of Blitzkrieg tactics would have made a German victory almost inevitable. A more modern writer using this conceptual framework is Eugen Weber in his The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s (1994).

In France this approach to the subject has always remained popular, as shown by later works as Jean-Baptiste Duroselle's La Décadence (1979). Especially outside France[80] in reaction to these traditional "decadentist" works a more revisionist school has developed.[81] Revisionist historians emphasize on the one hand the very deep structural demographic and economic disadvantages for France, that would have made it difficult to attain parity with Germany in any event, whatever the state of the people, leadership or command; and on the other hand the fundamental contingency of history, indicating the actual choice for a strategy as the main cause of defeat. When the structural approach is dominant it often results in depicting the French defeat as predetermined by the circumstances, whereas the more "contingent" view tends to consider a French defensive success as quite possible.