Battle of Leyte Gulf

| Battle of Leyte Gulf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theatre of World War II | |||||||

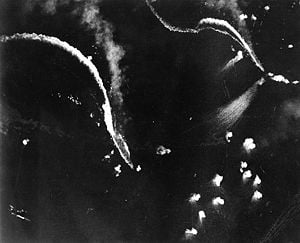

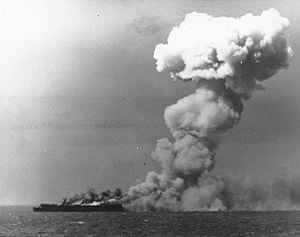

The light aircraft carrier Princeton afire, east of Luzon, October 24, 1944. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

(3rd Fleet) (7th Fleet) |

20x22px | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17 aircraft carriers 18 escort carriers 12 battleships 24 cruisers 141 destroyers and destroyer escorts Many PT boats, submarines and fleet auxiliaries About 1,500 planes |

4 aircraft carriers 9 battleships 19 cruisers 34 destroyers About 200 planes | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 3,500 dead; 1 aircraft carrier, 2 escort carriers, 2 destroyers, 1 destroyer escort sunk |

10,000 dead; 4 aircraft carriers, 3 battleships, 8 cruisers, 12 destroyers sunk | ||||||

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, also known as the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea, was the largest naval battle in modern history. It was fought in the Pacific Theater of World War II, in the seas surrounding the Philippine island of Leyte, from October 23 to October 26, 1944, between the Allies and the Empire of Japan. The Allies commenced the invasion of Leyte in order to cut off Japan from her South East Asia colonies and hamper the source of crucial oil supplies for the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Japanese gathered all their remaining major naval forces in an attempt to repel the Allied troops, but they failed to achieve their objective and also suffered heavy losses. The battle was the last major naval engagement of World War II; the Imperial Japanese Navy never again sailed to battle in such large force, being deprived of their fuel, returning to Japan to sit inactive for the remainder of the war until April 1945, and Operation Ten-ichi-go (meaning "Operation Heaven One") when the Japanese Navy sent its remaining ships, including the Battleship Yamato on a suicide mission against the Allied force invading Okinawa.

The "Battle" of Leyte Gulf was actually a campaign consisting of four interrelated battles: The Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, the Battle of Surigao Strait, the Battle of Cape Engaño, and the Battle off Samar.

| Philippines campaign (1944â45) |

|---|

| Leyte â Leyte Gulf â Ormoc Bay â Mindoro â Lingayen Gulf â Luzon â Cabanatuan â Bataan â Manila â Corregidor â Los Baños â Palawan â Visayas â Mindanao |

The first use of kamikaze aircraft was during this battle. A kamikaze hit the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia, on October 21, and organized suicide attacks by the "Special Attack Force" began on October 25. The crushing of the Japanese navy resulting from this allied victory raised questions about the necessity of dropping the Atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagaski, which for some undermines the morality of the war. Could Japan, unable to launch a naval defense have resisted indefinitely, so that only the nuclear option could end the conflict? These questions for many are answered by the ferocity with which the Japanese fought to the last man in the battles for the islands of Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. At the close of World War II, such awaited any invader of the Japanese home islands.

Background

The Pacific campaign of 1943 had driven the Imperial Japanese Army from many of its island bases in the Solomon Islands while isolating others, and in 1944, a series of Allied amphibious landings supported by large carrier forces captured the Northern Mariana Islands giving them a base from which long range B-29 Superfortress bombers could threaten the Japanese islands. The Japanese counterattacked in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, in which the Allies destroyed three Japanese aircraft carriers and approximately 600 aircraft, establishing Allied air and sea superiority over the Central Pacific. (The aerial battle was so one-sided in favor of the Allies that it was nicknamed "The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.")

For subsequent operations, Admiral Ernest J. King and other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff favored blockading Japanese forces in the Philippines and attacking Formosa to give the Allies control of the sea routes between Japan and southern Asia. General Douglas MacArthur favored an invasion of the Philippines, which also lay across the supply lines to Japan. Leaving the Philippines in Japanese hands would be a blow to American prestige and a personal affront to General MacArthur, who in 1942, had famously vowed to return. Also, the considerable air power the Japanese had amassed in the Philippines was considered too dangerous to bypass by many high-ranking officers outside the Joint Chiefs of Staff, including Admiral Chester Nimitz. However, Nimitz and MacArthur initially had opposing plans, with Nimitz' plan initially centered on an invasion of Formosa, since that could also cut the supply lines to Southeast Asia. Formosa could also serve as a base for an invasion of mainland China, which MacArthur felt unnecessary. A meeting between MacArthur, Nimitz, and President Franklin Roosevelt helped confirm the Philippines as a strategic target but had less to do with the final decision to invade the Philippines than sometimes claimed. Nimitz eventually changed his mind and agreed to MacArthur's plan.[1]

The Allied options were equally apparent to the Imperial Japanese Navy. Combined Fleet Chief Toyoda Soemu prepared four "victory" plans: ShĆ-Go 1 (ShĆ ichigĆ sakusen) was a major naval operation in the Philippines, while ShĆ-Go 2, Sho-Go 3, and Sho-Go 4 were responses to attacks on Formosa, the Ryukyu and Kurile Islands respectively. The plans were complex, aggressive operations committing all available forces to a decisive battle, ignoring Japan's strategic immobility because of a lack of oil.

Thus, when on October 12, 1944, Nimitz launched a carrier raid against Formosa to make sure planes based there could not intervene in the Leyte landings, the Japanese put ShĆ-Go 2 into action, launching waves of attacks against the carriers, losing 600 planes in three days, almost their entire air force in the region. Following the American invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese Navy transitioned to ShĆ-Go 1.

ShĆ-Go 1 called for Vice-Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa's fleet, known as Northern Force, to lure the U.S. Third Fleet away from the landings using an obviously vulnerable force of carriers, which were in fact mostly empty of aircraft. The Allied landing forces, lacking air cover, would then be attacked from the west by three Japanese forces: Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita's command, Center Force, based in Brunei, would enter Leyte Gulf and destroy the Allied landing forces. Rear-Admiral Shoji Nishimura's and Vice-Admiral Kiyohide Shima's fleets, collectively called Southern Force, would act as mobile strike forces. All three forces would consist of surface ships.

The plan was likely to result in the destruction of one or more of the forces, but Toyoda later justified it to his American interrogators as follows:

Should we lose in the Philippines operations, even though the fleet should be left, the shipping lane to the south would be completely cut off so that the fleet, if it should come back to Japanese waters, could not obtain its fuel supply. If it should remain in southern waters, it could not receive supplies of ammunition and arms. There would be no sense in saving the fleet at the expense of the loss of the Philippines.

Battle of the Sibuyan Sea

Kurita's powerful "Center Force" consisted of five battleships (Yamato, Musashi, Nagato, KongĆ, and Haruna), and twelve cruisers (Atago, Maya, Takao, ChĆkai, MyĆkĆ, Haguro, Noshiro, Kumano, Suzuya, Chikuma, Tone, and Yahagi), supported by thirteen destroyers.

As Kurita passed Palawan Island shortly after midnight on October 23, his force was spotted by the submarines USS Dace and USS Darter. Although the submarines' report of the sighting was picked up by the radio operator on Yamato, the Japanese failed to take anti-submarine precautions. Kurita's flagship Atago was sunk by Darter and Maya by Dace. Kurita transferred his flag to Yamato. Takao was also severely damaged and turned back to Brunei with two destroyers, shadowed by the submarines. On October 24, Darter grounded on the Bombay Shoal. All efforts to get her off failed, and she was abandoned; her entire crew was rescued by Dace.

At about 8:00 a.m. on October 24, the force was spotted entering the narrow Sibuyan Sea by planes from USS Intrepid.[2] Two hundred and sixty planes from carriers Intrepid and Cabot of Task Group 38.2 attacked at about 10:30 a.m., scoring hits on Nagato, Yamato, Musashi, and severely damaging MyĆkĆ. The second wave of planes concentrated on Musashi, scoring many direct hits with bombs and torpedoes. As she retreated, listing to port, a third wave from USS Enterprise and USS Franklin hit her with eleven bombs and eight torpedoes. Kurita turned his fleet around to get out of range of the planes, passing the crippled Musashi as he retreated.[3] He waited until 5:15 p.m. before turning around again to head for the San Bernardino Strait.[4] Musashi finally rolled over and sank at about 7:30 p.m. Kurita made his way through the San Bernardino Strait in the night, to appear off Samar in the morning.

Meanwhile, Vice-Admiral Onishi Takijiro had directed his First Air Fleet of 80 planes based on Luzon against the carriers USS Essex, USS Lexington, USS Princeton, and USS Langley of Task Group 38.3 (whose planes were being used to attack airfields in Luzon to prevent Japanese land based aircraft attacks on the Allied ships in the Leyte Gulf). The ships were hit with a massive barrage from the air.[5]Princeton was hit by an armor-piercing bomb and burst into flames. At 3:30 p.m., the aft magazine exploded, killing 200 sailors on Princeton and 80 on the cruiser USS Birmingham which was alongside assisting with the firefighting. Birmingham was so badly damaged that she was forced to retire, and other nearby vessels were damaged, too. All efforts to save Princeton failed, and she was scuttled two hours later, at 5:50 p.m.

Battle of Surigao Strait

Nishimura's "Southern Force" consisted of the battleships Yamashiro and FusĆ, the cruiser Mogami, and four destroyers. They were attacked by bombers on October 24, but sustained only minor damage.

Because of the strict radio silence imposed on the Central and Southern Forces, Nishimura was unable to synchronize his movements with Shima and Kurita. When he entered the narrow Surigao Strait at about 2:00 a.m., Shima was 25 miles (40 km) behind him, and Kurita was still in the Sibuyan Sea, several hours from the beaches at Leyte.

As they passed the cape of Panaon Island, they ran into a deadly trap set for them by the 7th Fleet Support Force. Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf had six battleships (Mississippi, Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania, all but the Mississippi having been resurrected from Pearl Harbor), eight cruisers (heavy cruisers USS Louisville, the flagship, Portland, Minneapolis, and HMAS Shropshire, light cruisers USS Denver, Columbia, Phoenix, Boise), 28 destroyers and 39 Patrol/Torpedo (PT) boats. To pass the strait and reach the landings, Nishimura would have to run the gauntlet of torpedoes from the PT boats, evade two groups of destroyers, proceed up the strait under the concentrated fire of six battleships in line across the far mouth of the strait, and then break through the screen of cruisers and destroyers.[6]

At about 3:00 a.m., FusĆ and the destroyers Asagumo, Yamagumo, and Mishishio were hit by torpedoes launched by the destroyer groups. FusĆ broke in two but did not sink. Then at 3:16 a.m., USS West Virginia's radar picked up Nishimura's force at a range of 42,000 yards (38 km) and had achieved a firing solution at 30,000 yards (33 km). She tracked them as they approached in the pitch black night. At 3:52 a.m., West Virginia unleashed her eight 16 inch (406 mm) guns of the main battery at a range of 22,800 yards (25 km), striking the leading Japanese battleship with her first salvo. At 3:54 a.m., USS California and USS Tennessee opened fire. Radar fire control allowed these American battleships to hit targets from a distance at which the Japanese could not reply because of their inferior fire control systems. Yamashiro and Mogami were crippled by a combination of 14-inch (356mm) and 16-inch (406 mm) armor-piercing shells. Shigure turned and fled but lost steering and stopped dead. Yamashiro sank at 4:19 a.m., with Nishimura on board. His surviving ships retreated west. The Japanese fleet had been shelled so relentlessly that it had little time to react and retaliate.[7]

At 4:25 a.m., Shima's two cruisers (Nachi and Ashigara) and eight destroyers reached the battle. Seeing what they thought were the wrecks of both Nishimura's battleships (actually the two halves of FusĆ), he ordered a retreat. His flagship, Nachi, collided with Mogami, flooding the latter's steering-room. Mogami fell behind in the retreat and was sunk by aircraft the next morning. The bow half of FusĆ was destroyed by Louisville, and the stern half sank off Kanihaan Island. Of Nishimura's seven ships, only Shigure survived.

The Battle of Surigao Strait was, to date, the final line battle in naval history. Yamashiro was the last battleship to engage another in combat and one of very few to have been sunk by another battleship during World War II. This was also the last battle in which one force (the Americans, in this case) was able to cross the T of its opponent, enabling the U.S. ships to bring all their firepower to bear on the Japanese ships.

Battle off Cape Engaño

The crew of Zuikaku salute as the flag is lowered, and the Zuikaku ceases to be the flagship of the Imperial Japanese Navy. |

Ozawa's "Northern Force" had four aircraft carriers (Zuikakuâthe last surviving carrier of the Attack on Pearl HarborâZuihĆ, Chitose, and Chiyoda), two World War I battleships partially converted to carriers (HyĆ«ga and Iseâthe aft turrets had been replaced by hangar, deck and catapult, but neither carried any planes in this battle), three cruisers (Ćyodo, Tama, and Isuzu), and nine destroyers. He had only 108 planes.

Ozawa's force was not spotted until 4:40 p.m. on October 24, because the Americans were too busy attacking Kurita and dealing with the air strikes from Luzon. On the evening of October 24, Admiral Ozawa intercepted a (mistaken) American communication of Kurita's withdrawal and began to withdraw as well. But at 8:00 p.m, Toyoda Soemu ordered all forces to attack.

Halsey saw that he had an opportunity to destroy the last Japanese carrier forces in the Pacific, a blow that would completely destroy Japanese sea power and allow the U.S. Navy to attack the Japanese homelands. Believing that Kurita had been defeated by the airstrikes in the Sibuyan Sea and was retiring to Brunei, Halsey radioed Admiral Kinkaid at Leyte: "Central Force heavily damaged according to strike reports. Am proceeding north with three groups to attack carrier forces at dawn." From this dispatch, Kinkaid assumed that Halsey had left one of his groups behind to cover San Bernardino. What he had no way of knowing was that Halsey only had three carrier groups in the area. Admiral McCain's TG 38.1 was some 600 miles (1,000 km) to the east conducting refueling operations. Halsey set out in pursuit of Ozawa just after midnight with his three carrier groups and the battleships of Admiral Willis A. Lee's Task Force 34. In so doing, Halsey or members of his staff ignored reports from scout planes from the USS Independence that Kurita had turned back towards San Bernardo Strait and that the navigation lights in the strait had been turned on. When Admiral G.F. Bogan, commanding TG 38.2, radioed this information to Halsey's flagship, he was rebuffed by a staff officer, who replied "Yes, yes, we have that information." Admiral Willis A. Lee, who had correctly recognized that Admiral Ozawa's force was a decoy and indicated the same in a blinker message to Halsey's ship, was similarly rebuffed.

The U.S. Third Fleet was formidable and completely outgunned the Japanese Northern Force. Halsey had six fleet carriers (Intrepid, Franklin, Lexington, Bunker Hill, Enterprise, and Essex), five light carriers (a sixth, Princeton was destroyed by a Japanese air attack just as its planes were taking off to attack Center Force) (Independence, Belleau Wood, Langley, Cabot, and San Jacinto), six battleships (Alabama, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Jersey, South Dakota, and Washington), seventeen cruisers and sixty-three destroyers. He could put more than 1,000 planes in the air. It left the landings on Leyte covered only by a handful of escort carriers and destroyers.

On the morning of October 25, Ozawa launched 75 planes to attack the Americans, doing little damage. Most were shot down by the American covering patrols. A handful of survivors made it to Luzon.

The American carriers launched their first wave, 180 aircraft, at dawn, before the Northern Force had been located. The search aircraft made contact at 7:10 a.m. At 8:00 a.m., the American fighters destroyed the defensive screen of 30 aircraft. Air strikes began and continued until the evening, by which time the American aircraft had flown 527 sorties against the Northern Force, sinking Zuikaku and ZuihĆ, "seaplane tender" Chiyoda, and the destroyer Akitsuki. "Seaplane tender" Chitose was disabled, as was the cruiser Tama. Ozawa transferred his flag to Ćyodo.

With all the Japanese carriers sunk or disabled, the main targets remaining were the converted battleships Ise and Hyƫga. Their massive construction proved resistant to the air strikes, so Halsey sent Task Force 34 forward to engage them directly. During the entire battle, Halsey had been ignoring repeated calls for help from Taffy III and the other escort groups. At 10:00 a.m., Halsey received two messages. The first was from Kinkaid, which read: "MY SITUATION IS CRITICAL. FAST BATTLESHIPS AND SUPPORT BY AIR STRIKES MAY BE ABLE TO KEEP ENEMY FROM DESTROYING CVES AND ENTERING LEYTE." Halsey was shocked at this message. The radio signals from the Seventh Fleet had come in at random and out of order (communications had to be sent first to an overworked signal office, and then the message would be routed to the other fleet. The backlog in this office was tremendous); Halsey knew that Kinkaid was in trouble, but he had not dreamed of the scale. From 3,000 miles (5,000 km) away in Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz had been monitoring the desperate calls from Taffy III and sent Halsey a terse message: "TURKEY TROTS TO WATER WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR REPEAT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR RR THE WORLD WONDERS" The first four words and the last four were "padding" used to confuse enemy listeners (the end of the true message was marked by a double consonant, followed by nonsense words.) The communication's technician on Halsey's flagship correctly deleted the first section of padding but mistakenly kept the last four words in the message draft that was handed to Halsey. The last four words, probably selected by a communication's officer at Nimitz' headquarters, may have been meant as a loose quote from Tennyson's poem on "The Charge of the Light Brigade," in honor of the October 25 anniversary of the Battle of Balaklava and was not intended as a commentary on Halsey's current situation. Halsey, however, upon reading the message, thought that the last four words comprised a biting piece of criticism from Nimitz and broke into "sobs of rage." Realizing their mistake, the communications staff on Halsey's ship later explained to Halsey what had happened.[8]

Halsey reluctantly abandoned the pursuit and turned south, detaching only a small force of cruisers and destroyers under Laurence T. DuBose to sink the disabled Japanese ships. It was too late; Kurita had already turned for home. In what became known as the "Battle of Bull's Run," Halsey accomplished nothing except sinking a crippled Japanese cruiser. Ise and Hyƫga returned to Japan, where they were sunk at their moorings in 1945.

Battle off Samar

Kurita's center force passed through San Bernardino Strait at 3:00 a.m. on October 25, and steamed south along the coast of Samar, hoping that Halsey had taken the bait and led most of his fleet away.

To stop them, there were only three groups of light ships of the Seventh Fleet commanded by Admiral Thomas Kinkaid. Each had six small escort carriers, and seven or eight lightly armed and unarmored destroyers and/or smaller destroyer escorts. Admiral Thomas Sprague's Task Unit 77.4.1 (Taffy I) consisted of the escort carriers Sangamon, Suwannee, Santee, and Petrof Bay. (The remaining two escort carriers from Taffy I, Chenango and Saginaw Bay, had departed for Morotai, Indonesia, on October 24, carrying "dud" aircraft from other carriers for transfer ashore. They returned with replacement aircraft after the battle.) Admiral Felix Stump's Task Unit 77.4.2 (Taffy II) consisted of Natoma Bay, Manila Bay, Marcus Island, Kadashan Bay, Savo Island, and Ommaney Bay.

Admiral Clifton Sprague's Task Unit 77.4.3 (Taffy III) consisted of Fanshaw Bay, St Lo, White Plains, Kalinin Bay, Kitkun Bay, and Gambier Bay.

Each escort carrier carried about 30 planes, making available more than 500 planes in all, though many were armed with machine guns and depth charges effective only against submarines or destroyers. The escort carriers were slow and lightly armored and stood little chance in an encounter with a battleship. They were, however, "screened" by destroyers and destroyer escorts affectionately known as "tin cans."

A mix up in communications led Kinkaid to believe that Willis A. Lee's Task Force 34 of battleships was guarding the San Bernardino Strait to the north and that there would be no danger from that direction. Thomas Sprague assumed that Halsey was taking three of his carrier groups to attack and would be leaving one group behind to guard the Strait. But Lee had gone with Halsey (who had, in fact, taken all four of his carrier groups) in pursuit of Ozawa. The Japanese came upon Taffy III at 6:45 a.m., taking the Americans completely by surprise. Kurita, not seeing the silhouettes of the tiny escort carriers in his identification manuals, mistook the escort carriers for fleet carriers and thought that he had the whole of the American Third Fleet under guns of his battleships, including the 18.1-inch (460 mm) guns of the Yamato.

When Taffy III discovered they were coming under attack, Clifton Sprague (no relation to Thomas Sprague) directed his Taffy III carriers to turn to launch their aircraft and flee towards a squall to the east, hoping that bad visibility would reduce the accuracy of Japanese gunfire, and ordered the destroyers to make smoke to mask the retreating carriers, which drew fire from the Japanese ships. The History Channel's 2006 program, Dogfights, called it the naval mismatch of the century, wherein David would send Goliath fleeing for home. Yamato was the largest and most powerful battleship to ever see combat; it alone displaced as much as all of Taffy put together.

Concerned about the splashes of incoming fire, Lieutenant Commander Ernest E. Evans, skipper of the destroyer USS Johnston, which was the closest to the attackers, suddenly took the initiative to order his ship to "flank speed, full left rudder," ordering Johnston to directly attack the greatly superior oncoming Japanese ships on his own in what would appear to be a suicidal mission.

The Johnston was a relatively small and unarmored destroyer, completely unequipped to fight Japanese battleships and cruisers. Designed to fight other destroyers and torpedo boats, she was armed with only five 5-inch guns and multiple anti-aircraft weapons which were ineffective against an armored battleship. Only the Johnstonâs 10 Mark-15 torpedoes could be effective, but they had to be launched well within range of enemy gunfire.

Weaving to avoid shells, and steering towards splashes, the Johnston approached the Japanese heavy cruiser Kumano for a torpedo run. When Johnston was 10 miles (17 km) from Kumano, her 5-inch guns rained shells on Kumanoâs bridge and deck (where they could do some damageâthe shells would simply bounce off the enemy ship's armored hull). Johnston closed to within torpedo range and fired a salvo, which blew the bow off the cruiser squadron flagship, Kumano, and also took the cruiser Suzuya out of the fight, as she stopped to assist.

From seven miles (11 km) away, the battleship Kongo sent a 14 inch shell through the Johnstonâs deck and engine room. Johnstonâs speed was cut in half to only 14 knots, while the aft gun turrets lost all electrical power. Then three 6-inch shells, possibly from Yamato's secondary batteries, struck Johnstonâs bridge, killing many and wounding Commander Evans. The bridge was abandoned, and Evans steered the ship from the aft steering column. Evans nursed his ship back towards the fleet, when he saw the other destroyers attacking as well. Emboldened by the Johnston's attack, Sprague gave the order "small boys attack," sending the rest of Taffy IIIs destroyers on the assault. Even in her heavily damaged state, damage-control teams restored power to 2 of the 3 aft turrets, and Evans turned the Johnston around and re-entered the fight.

The other destroyers attacked the Japanese line with suicidal determination, drawing fire and scattering the Japanese formations as ships turned to avoid torpedoes. The powerful Yamato found herself between two torpedoes fired from the destroyer USS Heermann which were on parallel courses, and for ten minutes, she headed away from the action, unable to turn back for fear of being hit. Heermann, meanwhile, closed with the other Japanese battleships, advancing so close to her huge targets that they could not fire for either inability to depress their main guns enough or fear of hitting their own men and ships.

At 7:35 a.m., the even smaller destroyer escort USS Samuel B. Roberts turned and headed toward the battle. On the way, the Roberts passed by the mangled Johnston and saw an inspirational sight in the person of Commander Evans standing on the Johnstonâs stern, his left hand bandaged, saluting the captain of the Roberts. With only two 5-inch guns, one fore and aft, and just 3 Mark-15 torpedoes, Roberts crew lacked the weapons and training in tactics to take on the much larger attackers. Still, she charged in to attack the heavy cruiser Chokai. With smoke as cover, the Roberts steamed to within two and a half miles (4 km) of Chokai, coming under fire of her two forward 8-inch turrets. But Roberts was so close that the shells passed overhead. Once in torpedo range, Roberts' fired torpedoes. The entire salvo struck the cruiser. Following this, Roberts dueled with the Japanese ships for an hour, firing more than 600 5-inch shells and raking their upper works with 40 mm Bofors and 20 mm anti-aircraft guns while maneuvering at close range. At 8:51 a.m., the Japanese finally landed two hits, the second of which destroyed the aft gun turret. With her remaining 5-inch gun, Roberts set the bridge of the cruiser Chikuma afire and destroyed the number 3 gun turret, before being pierced yet again by three 14 inch shells from the Kongo. With a 40-foot (12 m) hole in her side, the Roberts took on water, and at 9:35 a.m., the order was given to abandon ship, sinking 30 minutes later with 89 of her crew.[9]

Meanwhile, Thomas Sprague had ordered all three Taffy groups to launch their planes with whatever they had, even if their remaining armament was only machine guns or depth charges. Even after many aircraft expended their ammunition they made dry runs to threaten and distract Japanese warships and their gunners. Instead of being overrun, the American Navy had turned the battle into into a bloody all-out brawl with their Japanese attackers.

The carriers of Taffy III turned south and fled through shellfire. The armor-piercing (AP) shells intended for Halsey's battleships flew right through the thin-skinned escort carriers without triggering their fuses. A switch to High Explosive (HE) shells holed, slowed, and sunk the Gambier Bay at the rear, while most of the others were also damaged. Their single stern-mounted five-inch (127 mm) anti-aircraft guns returned fire, though they were ineffective against surface ships. Yet, the St. Lo scored a hit on the magazine of a cruiser, the only known hit inflicted directly by a gun on an aircraft carrier against an opposing surface vessel.

The tide soon turned against Taffy III's destroyers. Two hours into the attack, Commander Evans aboard the Johnston spotted a line of four destroyers led by the light cruiser Yahagi making a torpedo attack on the fleeing carriers and moved to intercept. Johnston poured fire on the attacking group, forcing them to prematurely fire their torpedoes, missing the carriers. Their gunfire then turned to the weaving Johnston. At 9:10 a.m., the Japanese scored a direct hit on one of the forward turrets, knocking it out and setting off many 5-inch shells that were stored in the turret, and her damaged engines stopped, leaving her dead in the water. The Japanese destroyers closed in on the sitting target, and the Johnston was hit so many times that one survivor recalled "they couldn't patch holes fast enough to keep her afloat." At 9:45 a.m. (2 hours and 45 minutes into the battle), Evans finally gave the order to abandon ship. The Johnston sank 25 minutes later, with 186 of her crew. Commander Evans abandoned ship with his crew but was never seen again. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Just as it seemed the end was near for the Taffy III and the other two Taffy groups, at 9:20 a.m. Kurita suddenly broke off the fight and, giving the order "all ships, my course north, speed 20," retreated north. Though many of his ships were not even damaged, the air and destroyer attacks had broken up his formations, and he had lost tactical control. Three heavy cruisers (ChĆkai, Kumano, Chikuma) had been sunk, and the ferocity of the determined concentrated sea and air attack had led him to calculate that continuing was not worth further losses.

Signals from Admiral Ozawa had disabused him of the notion that he was attacking the whole of the 3rd Fleet, which meant that the longer he continued to engage, the more likely it was that he would suffer devastating air strikes from Halsey's main attack carriers which were even more threatening than the tiny force of Taffy III. He retreated north and then west through the San Bernardino Strait. Nagato, Haruna, and KongĆ were severely damaged from the torpedoes of Taffy III's destroyers. Kurita had begun the battle with five battleships. On return to Japan, only Yamato remained combat-worthy, and she had not even taken a major part in the battle.

The spirit of Taffy III was shown when, while watching the Japanese retreat, Sprague heard a nearby sailor exclaim: "Dammit boys, they're getting away!"

The American destroyers Hoel and Johnston and destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts were sunk, and four others were damaged. The destroyer Heermann, despite her duel with Japanese battleships many times her size, finished the battle with only six of her crew dead. In total, more than one thousand American sailors and pilots were killed.

Taffy III was awarded the following Presidential Unit Citation:

For extraordinary heroism in action against powerful units of the Japanese Fleet during the Battle off Samar, Philippines, October 25, 1944. âŠthe gallant ships of the Task Unit waged battle fiercely against the superior speed and fire power of the advancing enemy âŠtwo of the Unit's valiant destroyers and one destroyer escort charged the battleships point-blank and, expending their last torpedoes in desperate defense of the entire group, went down under the enemy's heavy shells ⊠The courageous determination and the superb teamwork of the officers and men who fought the embarked planes and who manned the ships of Task Unit 77.4.3 were instrumental in effecting the retirement of a hostile force threatening our Leyte invasion operations and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Aftermath

The battle of Leyte Gulf secured the beachheads of the U.S. Sixth Army on Leyte against attack from the sea. However, much hard fighting would be required before the island was completely in Allied hands at the end of December 1944: The Battle of Leyte on land was fought in parallel with an air and sea campaign in which the Japanese reinforced and resupplied their troops on Leyte while the Allies attempted to interdict them and establish air-sea superiority for a series of amphibious landings in Ormoc Bayâengagements collectively referred to as the Battle of Ormoc Bay.

The Imperial Japanese Navy was not destroyed or eliminated, as some accounts have described, since the greater part of the fleet survived the battle. However, their failure to dislodge the Allied invaders from Leyte meant that Japan would be cut off from her colonies in Southeast Asia, which provided crucial war resources, such as oil for their ships, and the problem was compounded because the shipyards and ammunition were in Japan. The fleet returned home to sit inactive for the remainder of the war. The loss of Leyte opened the way for the invasion of the Ryukyu Islands in 1945. The only significant Japanese naval operation for the rest of the war was the disastrous Operation Ten-Go in April 1945.

Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi had put his "Special Attack Force" into operation, launching kamikaze attacks against the Allied ships in Leyte Gulf, but it was hampered by bad weather and fuel shortages. This was a turning point, as kamikazes were a new development.[10] When defense had failed, suicide was employed in an attempt to attain it.[11] On October 25, Australia was hit for a second time and forced to retire for repairs, while the escort carrier St. Lo was sunk. Because of communication errors, the Taffy III survivors of the Battle off Samar who had abandoned ship were not rescued for a few days, by which time many more had gone mad or died because of sharks or thirst. Finally, the captain of an LST took his ship to rescue the Americans, using a rather peculiar method of identifying who was American, as survivor Jack Yusen related:

We saw this ship come up, it was circling around us, and a guy was standing up on the bridge with a megaphone. And he called out "Who are you? Who are you?" and we all yelled out "Samuel B. Roberts!" He's still circling, so now we're cursing at him. He came back and yelled "Who won the World Series?" and we all yelled "St. Louis Cardinals!" And then we could hear the engines stop, and cargo nets were thrown over the side. That's how we were rescued.

The Japanese had been deprived of the fleet it required in order to achieve victory, yet they would keep on fighting and killing until the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealed to them the futility of their attempts.[12]

Criticism of Halsey

Halsey was criticized for his decision to abandon San Bernardino Strait[12] and take Task Force 34 with him in pursuit of Ozawa, and for failing to dispatch it when Kinkaid first appealed for help. U.S. Navy slang for Halsey's action has ever since been "Bull's Run," a neologism combining Halsey's nickname "Bull" and the Battles of Bull Run in the American Civil War. In his dispatch after the battle, Halsey justified the decision as follows:

Searches by my carrier planes revealed the presence of the Northern carrier force on the afternoon of October 24, which completed the picture of all enemy naval forces. As it seemed childish to me to guard statically San Bernardino Strait, I concentrated TF 38 during the night and steamed north to attack the Northern Force at dawn. I believed that the Center Force had been so heavily damaged in the Sibuyan Sea that it could no longer be considered a serious menace to Seventh Fleet.

Furthermore, to leave Task Force 34 to defend the strait without carrier support would have left them vulnerable to attack from land-based aircraft. From previous experience, Halsey knew that the Japanese had the ability to move planes from Japan into the area very quickly. Leaving one of Third Fleet's three remaining Task Groups behind to cover the battleships would have significantly reduced the amount of air power, although Admiral Lee would later state that "one or two light carriers" might have been sufficient cover. Finally, the fact that Halsey was aboard a battleship and would have to remain with Task Force 34 while the majority of the fleet sailed north might also have contributed to his decision.

Clifton Sprague, commander of Task Unit 77.4.3 in the battle off Samar, was later critical of Halsey's decision: "In the absence of any information that this exit [of the San Bernardino Strait] was no longer blocked, it was logical to assume that our northern flank could not be exposed without ample warning."

Naval historian Samuel Morison wrote:

If TF 34 had been detached a few hours earlier, after Kinkaid's first urgent request for help, and had left the destroyers behind, since their fueling caused a delay of more than two hours and a half, a powerful battle line of six modern battleships under the command of Admiral Lee, the most experienced battle squadron commander in the Navy, would have arrived off San Bernardino Strait in time to have clashed with Kurita's Center Force⊠Apart from the accidents common in naval warfare, there is every reason to suppose that Lee would have crossed Kurita's T and completed the destruction of Center Force.

Audio/visual media

- Lost Evidence of the Pacific: The Battle of Leyte Gulf. History Channel. TV.

- Dogfights: Death of the Japanese Navy. History Channel. TV.

Notes

- â Robert Ross Smith, Luzon Versus Formosa (Washington: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1944), 463-477.

- â Edwin P. Hoyt, The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Death Knell of the Japanese Fleet (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1972), 106.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 107.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 131.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 149.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 171.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 191.

- â E.B. Potter, Admiral Arleigh Burke (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2005).

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 223-224.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 289.

- â Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 291.

- â 12.0 12.1 Hoyt, Battle of Leyte Gulf, 297.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cutler, Thomas. The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23-26 October 1944. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001. ISBN 1557502439

- D'Albas, Andrieu. Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Old Greenwich: Devin-Adair Publishing, 1965. ISBN 081595302X

- Dull, Paul S. A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1978. ISBN 0870210971

- Field, James A. The Japanese at Leyte Gulf;: The Sho operation. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1947.

- Friedman, Kenneth A. Afternoon of the Rising Sun: The Battle of Leyte Gulf. New York: Presidio Press, 2001. ISBN 0891417567

- Hornfischer, James D. The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors. New York: Bantam, 2004. ISBN 0553802577

- Hoyt, Edwin P. The Battle of Leyte Gulf: The Death Knell of the Japanese Fleet. New York: Weybright and Talley, 1972.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. The Men of the Gambier Bay: The Amazing True Story of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Guilford: The Lyons Press, 2003. ISBN 1585746436

- Lacroix, Eric, and Linton Wells. Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 0870213113

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 12, Leyte, June 1944-January 1945. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2002. ISBN 0252070631

- Potter, E.B. Admiral Arleigh Burke. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2005. ISBN 1591146925

- Potter, E.B. Bull Halsey. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2003. ISBN 1591146917

- Sauer, Howard. The Last Big-Gun Naval Battle: The Battle of Surigao Strait. El Cerrito: Glencannon Press, 1999. ISBN 1889901083

- Smith, Robert Ross. Luzon Versus Formosa. Washington: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1944.

- Thomas, Evan. Sea of Thunder: Four Commanders and the Last Great Naval Campaign 1941-1945. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0743252217

- Willmott, H.P. The Battle Of Leyte Gulf: The Last Fleet Action. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 0253345286

External links

All links retrieved September 22, 2023.

- Battle Experience: Battle for Leyte GulfâCominch Secret Information Bulletin No. 22

- Task Force 77 Action Report: Battle of Leyte Gulf

- "Glorious Death: The Battle of Leyte Gulf" by Tim Lanzendörfer

- The Battle Off Samar - Taffy III at Leyte Gulf by Robert Jon Cox

- Leyte Gulf Naval Chess Game, a free, educational boardgame of the battle, to print off, assemble, and play

- Return to the Philippines: public domain documents from ibiblio.org

- Orders of battle:

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.