Ashkenazi

| Ashkenazi Jews (יהודי אשכנז Yehudei Ashkenaz) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8[1] - 11.2[2] million (estimate) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, English | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judaism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and other Jewish ethnic divisions |

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim, are Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities of the Rhineland—"Ashkenaz" being the Medieval Hebrew name for Germany. The are distinguished from Sephardic Jews, the other group of European Jewry, who arrived earlier in Europe and lived primarily in Spain.

Many Ashkenazim later migrated, largely eastward, forming communities in Germany, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere between the tenth and nineteenth centuries. From medieval times until the mid-twentieth century, the lingua franca among Ashkenazi Jews was primarily Yiddish.

The Ashkenazi Jews developed a distinct culture and liturgy influenced, to varying degrees, by interaction with surrounding peoples, predominantly Germans, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Kashubians, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Letts, Belarusians, and Russians.

Although in the eleventh century they comprised only 3 percent of the world's Jewish population, Ashkenazi Jews accounted for 92 percent of the world's Jews in 1931, and today make up approximately 80 percent of Jews worldwide. Most Jewish communities with extended histories in Europe are Ashkenazim, with the exception of those associated with the Mediterranean region. A significant portion of the Jews who migrated from Europe to other continents in the past two centuries are Eastern Ashkenazim, particularly in the United States.

Who is an Ashkenazi Jew?

An Ashkenazi Jew can be defined religiously, culturally, or ethnically. Since the overwhelming majority of Ashkenazi Jews no longer live in Eastern Europe, the isolation that once fostered their distinct religious tradition and culture has vanished. Furthermore, the word "Ashkenazi" is itself evolving and taking on new meanings.

In a religious sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is any Jew whose family tradition and ritual follows Ashkenazi practice. When the Ashkenazi community first began to develop, the centers of Jewish religious authority were in the Islamic world, at Baghdad and in Islamic Spain. Ashkenaz (Germany) was so distant geographically that it developed a tradition of its own, and Ashkenazi Hebrew came to be pronounced in ways distinct from other forms of Hebrew.

In a cultural sense, an Ashkenazi Jew can be identified by the concept of Yiddishkeit, a word that literally means “Jewishness” in the Yiddish language. Originally this meant the study of Torah and Talmud for men, and a family and communal life governed by the observance of Jewish Law for men and women. From the Rhineland to Riga to Romania, most Jews prayed in liturgical Ashkenazi Hebrew, and spoke some dialect of Yiddish in their secular lives.

However, with modernization, Yiddishkeit began to encompass not just Orthodoxy and Hasidism, but a broad range of movements, ideologies, practices, and traditions in which Ashkenazi Jews have participated and somehow retained a sense of Jewishness. As Ashkenazi Jews moved away from Eastern Europe, settling mostly in North America and Israel, the geographic isolation which gave rise to Ashkenazim has given way to mixing with other cultures, and with non-Ashkenazi Jews who, similarly, are no longer isolated in distinct geographic locales. In Israel, Hebrew has replaced Yiddish as the primary Jewish language for the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews.

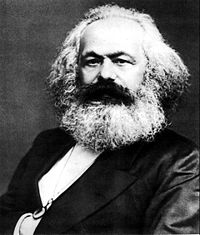

By tradition, Jewish status is inherited through the maternal lineage. Therefore, someone who is descended from a Jewish mother, even if totally unaware of their Jewish heritage, is a Jew. A large proportion of Ashkenazi Jews in Israel, the U.S., and the former Soviet Union are not religiously observant. Even a Jew who converts to another religion, though an apostate, is still considered a Jew. Karl Marx, an atheist whose Jewish mother and father had converted to Christianity before he was born, was an Ashkenazi Jew.

In an ethnic sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is one whose ancestry can be traced to the Jews of central and Eastern Europe. For roughly a thousand years, the Ashkenazi Jews were a reproductively isolated population in Europe.

However, since the middle of the twentieth century, many Ashkenazi Jews have intermarried, both with members of other Jewish communities and with people of other nations and faiths. Conversion to Judaism, rare for nearly 1500 years, has once again become common. Thus, the concept of Ashkenazi Jews as a distinct ethnic people, especially in ways that can be defined ancestrally and therefore traced genetically, has also blurred considerably.

In Israel, Jews of mixed background are increasingly common, partly because of intermarriage between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi partners, and partly because some do not identify with such historic markers as relevant to their life experiences as Jews. Religious Ashkenazi Jews living in Israel are obliged to follow the authority of the chief Ashkenazi rabbi in halakhic matters.

Ashkenazi migrations throughout the High and Late Middle Ages

Historical records show evidence of Jewish communities north of the Alps and Pyrenees as early as the eighth and ninth Century. By the early 900s, Jewish populations were well-established in Northern Europe, and later followed the Norman Conquest into England in 1066, also settling in the Rhineland. With the onset of the Crusades, and the expulsions from England (1290), France (1394), and parts of Germany (1400s), Jewish migration pushed eastward into Poland, Lithuania, and Russia.

Over this period of several hundred years, some have suggested, Jewish economic activity was focused on trade, business management, and financial services, due to Christian European prohibitions restricting certain activities by Jews, and preventing certain financial activities (such as "usurious" loans) between Christians.

By the 1400s, the Ashkenazi Jewish communities in Poland were the largest Jewish communities of the Diaspora. Poland at this time was a decentralized medieval monarchy, incorporating lands from Latvia to Rumania, including much of modern Lithuania and Ukraine. This area, which eventually fell under the domination of Russia, Austria, and Prussia (Germany), would remain the main center of Ashkenazi Jewry until the Holocaust.

Usage of the name

In reference to the Jewish peoples of Northern Europe and particularly the Rhineland, the word Ashkenazi is often found in medieval rabbinic literature. References to Ashkenaz in Yosippon and Hasdai ibn Shaprut's letter to the king of the Khazars would date the term as far back as the tenth century, as would also Saadia Gaon's commentary on Daniel 7:8.

The word "Ashkenaz" first appears in the genealogy in the Tanakh (Genesis 10) as a son of Gomer and grandson of Japheth. It is thought that the name originally applied to the Scythians (Ishkuz), who were called Ashkuza in Assyrian inscriptions, and lake Ascanius and the region Ascania in Anatolia derive their names from this group. The "Ashkuza" have also been linked to the Oghuz branch of Turks including nearly all Turkic peoples today from Turkey to Turkmenistan.

Ashkenaz in later Hebrew tradition became identified with the peoples of Germany, and in particular to the area along the Rhine where the Alamanni tribe once lived (compare the French and Spanish words Allemagne and Alemania, respectively, for Germany).

The autonym was usually Yidn, however.

Medieval references

In the first half of the eleventh century, Hai Gaon refers to questions that had been addressed to him from "Ashkenaz," by which he undoubtedly means Germany. Rashi in the latter half of the eleventh century refers to both the language of Ashkenaz[4] and the country of Ashkenaz.[5] During the twelfth century, the word appears quite frequently. In the Mahzor Vitry, the kingdom of Ashkenaz is referred to chiefly in regard to the ritual of the synagogue there, but occasionally also with regard to certain other observances.

In thirteenth-century literature, references to the land and the language of Ashkenaz often occur. See especially Solomon ben Aderet's Responsa (vol. i., No. 395); the Responsa of Asher ben Jehiel (pp. 4, 6); his Halakot (Berakot i. 12, ed. Wilna, p. 10); the work of his son Jacob ben Asher, Tur Orach Chayim (chapter 59); the Responsa of Isaac ben Sheshet (numbers 193, 268, 270).

In the Midrash compilation Genesis Rabbah, Rabbi Berechiah mentions "Ashkenaz, Riphath, and Togarmah" as German tribes or as German lands. It may correspond to a Greek word that may have existed in the Greek dialect of the Palestinian Jews, or the text is corrupted from "Germanica." This view of Berechiah is based on the Talmud (Yoma 10a; Jerusalem Talmud Megillah 71b), where Gomer, the father of Ashkenaz, is translated by Germamia, which evidently stands for Germany, and which was suggested by the similarity of the sound.

In later times, the word Ashkenaz is used to designate southern and Western Germany, the ritual of which sections differs somewhat from that of Eastern Germany and Poland. Thus, the prayer-book of Isaiah Horowitz, and many others, give the piyyutim according to the Minhag of Ashkenaz and Poland.

According to sixteenth-century mystic Rabbi Elijah of Chelm, Ashkenazi Jews lived in Jerusalem during the eleventh century. The story is told that a German-speaking Palestinian Jew saved the life of a young German man surnamed Dolberger. So when the knights of the First Crusade came to siege Jerusalem, one of Dolberger’s family members who was among them rescued Jews in Palestine and carried them back to Worms to repay the favor. Further evidence of German communities in the holy city comes in the form of halakic questions sent from Germany to Jerusalem during the second half of the eleventh century.[6]

Customs, laws and traditions

The collective corpus of Jewish religious law, including biblical law (the 613 mitzvot) and later, talmudic and rabbinic law as well as customs and traditions (Halakhic) of Ashkenazi Jews may differ from those of Sephardi Jews, particularly in matters of custom. Differences are noted in the Shulkhan Arukh (a codification, or written catalogue, of Halakha, composed by Rabbi Yosef Karo in the sixteenth century) itself, and in the writings of Moses Isserles (1520 - 1572), a rabbi and Talmudist, renowned for his fundamental work of Halakha, entitled HaMapah ("the tablecloth"). Well-known differences in practice include:

- Observance of Pesach (Passover): Ashkenazi Jews traditionally refrain from eating legumes, corn, millet, and rice (Quinoa, however, has become accepted as foodgrain in the North American communities), whereas Sephardi Jews typically do not prohibit these foods.

- Ashkenazi Jews freely mix and eat fish and milk products; some Sephardic Jews refrain from doing so.

- Ashkenazim are more permissive toward the usage of wigs as a hair covering for married and widowed women.

- In the case of Jewish dietary law (kashrut) for meat, conversely, Sephardi Jews have stricter requirements—this level is commonly referred to as Beth Yosef (Hebrew: "House of Joseph"), a comprehensive commentary on Jewish law going back to the Talmud and the Midrash.

Meat products which are acceptable to Ashkenazi Jews as kosher may therefore be rejected by Sephardi Jews. Notwithstanding stricter requirements for the actual slaughter, Sephardi Jews permit the rear portions of an animal after proper Halakhic removal of the sciatic nerve, while many Ashkenazi Jews do not. This is not because of different interpretations of the law; rather, slaughterhouses could not find adequate skills for correct removal of the sciatic nerve and found it more economical to separate the hindquarters and sell them as non-kosher meat.

- Ashkenazi Jews frequently name newborn children after deceased family members, but not after living relatives. Sephardi Jews, on the other hand, often name their children after the children's grandparents, even if those grandparents are still living. A notable exception to this generally reliable rule is among Dutch Jews, where Ashkenazim for centuries used the naming conventions otherwise attributed exclusively to Sephardim.)

- Ashkenazi tefillin (two boxes containing Biblical verses and the leather straps attached to them which are used in traditional Jewish prayer) bear some differences from Sephardic tefillin. In the traditional Ashkenazic rite the tefillin are wound towards the body, not away from it. Ashkenazim traditionally don tefillin while standing whereas other Jews generally do so while sitting down.

- Ashkenazic traditional pronunciations of Hebrew differ from those of other groups. The most prominent consonantal difference from Sephardic and Mizrahic Hebrew dialects is the pronunciation of the Hebrew letter tav at the end of many Hebrew words as an "s" and not a "t" or "th" sound.

Relationship to other Jews

|

The term Ashkenazi also refers to the nusach Ashkenaz (Hebrew, "liturgical tradition," or rite) used by Ashkenazi Jews in their Siddur (prayer book). A nusach is defined by a liturgical tradition's choice of prayers, order of prayers, text of prayers and melodies used in the singing of prayers. Two other major forms of nusach among Ashkenazic Jews are Nusach Sphard (not to be confused with Sephardi), which is the same as the general Polish (Hasidic) Nusach; and Nusach Chabad, otherwise known as Lubavitch Chasidic, Nusach Arizal, or Nusach he'Ari.

This phrase is often used in contrast with Sephardi Jews, also called Sephardim, who are descendants of Jews from Spain and Portugal. There are some differences in how the two groups pronounce Hebrew and in points of ritual.

Several famous people have this as a surname, such as Vladimir Ashkenazi. Ironically, most people with this surname are in fact Sephardi, and usually of Syrian Jewish background. This family name was adopted by the families who lived in Sephardi countries and were of Ashkenazic origins, after being nicknamed Ashkenazi by their respective communities. Some have shortened the name to Ash. Other spellings exist, such as Eskenazi by the Syrian Jews who relocated to Panama and other South-American Jewish communities.

Literature about the alleged Turkic origin of the Ashkenazi population, as descendants of the Jewish population, converts or otherwise, appeared mainly after 1950. Although it has speculated that the peaceful life lived by the Jews of Khazaria was contrived or exaggerated, and publicized primarily in an effort to shame European leaders into treating their Jewish populations better, the Jewish-Khazar thesis is used today primarily as a whipping horse for antisemites claiming that they are not antisemites. This dubious theory holds that Ashkenazi Jews should be hated for pretending to be Jews, instead of because they actually are Jews. In any case, most scholarship on the subject dismisses the Khazar-Ashkenazi relationship, if not rejecting the portrayed Jewish golden age of Khazaria altogether.

Modern history

In an essay on Sephardi Jewry, Daniel Elazar at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs[7] summarized the demographic history of Ashkenazi Jews in the last thousand years, noting that at the end of the eleventh century, 97 percent of world Jewry was Sephardic and 3 percent Ashkenazi; in the mid-seventeenth century, "Sephardim still outnumbered Ashkenazim three to two," but by the end of the eighteenth century "Ashkenazim outnumbered Sephardim three to two, the result of improved living conditions in Christian Europe versus the Muslim world."[7] By 1931, Ashkenazi Jews accounted for nearly 92 percent of world Jewry.[7]

Ashkenazi Jews developed the Hasidic movement as well as major Jewish academic centers across Poland, Russia, and Lithuania in the generations after emigration from the west. After two centuries of comparative tolerance in the new nations, massive westward emigration occurred in the 1800s and 1900s in response to pogroms and the economic opportunities offered in other parts of the world. Ashkenazi Jews have made up the majority of the American Jewish community since 1750.

Ashkenazi cultural growth led to the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment, and the development of Zionism in modern Europe.

Ashkenazi Jewry and the Holocaust

Of the estimated 8.8 million Jews living in Europe at the beginning of World War II, the majority of whom were Ashkenazi, about six million — more than two-thirds — were systematically murdered in the Holocaust. These included three million of 3.3 million Polish Jews (91 percent); 900,000 of 1.1 million in Ukraine (82 percent); and 50 to 90 percent of the Jews of other Slavic nations, Germany, France, Hungary, and the Baltic states. The only non-Ashkenazi community to have suffered similar depletions were the Jews of Greece. Many of the surviving Ashkenazi Jews emigrated to countries such as Israel, Australia, and the United States after the war.

Today, Ashkenazi Jews constitute approximately 80 percent of world Jewry, but probably less than half of Israeli Jews. Nevertheless they have traditionally played a prominent role in the media, economy, and politics of Israel. Tensions have sometimes arisen between the mostly Ashkenazi elite whose families founded the state, and later migrants from various non-Ashkenazi groups, who argue that they are discriminated against.

Achievement

Jews have a noted history of achievement in western societies. They have won a disproportionate share of major academic prizes, such as the Nobel awards and the Fields Medal in mathematics. In those societies where they have been free to enter any profession, they have a record of high occupational achievement, entering professions and fields of commerce where higher education is required. Discussion about the source or cause of high Jewish achievement, and the issue of whether it can be attributed to cultural, social, or genetic factors, is ongoing.

Notes

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbehar - ↑ John Hopkins Gazette, September 8, 1997.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gabriel E. Feldman,

PDF , Israel Medical Association Journal, Volume 3, 2001.

PDF , Israel Medical Association Journal, Volume 3, 2001.

- ↑ Commentary on Deuteronomy 3:9; idem on ''Talmud'' tractate Sukkah 17a

- ↑ Talmud, Hullin 93a

- ↑ Epstein, in "Monatsschrift," xlvii. 344; Jerusalem: Under the Arabs

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsephardic

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names: Their Origins, Structure, Pronunciations, and Migrations, Avotaynu, 2001. ISBN 1-886223-12-2

- Biale, David. Cultures of the Jews: A New History, Schoken Books, 2002. ISBN 0-8052-4131-0

- Goldberg, Harvey E. The Life of Judaism, University of California Press, 2001. ISBN 0-520-21267-3

- Silberstein, Laurence. Mapping Jewish Identities, New York University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8147-9769-5

- Vital, David. A People Apart: A History of the Jews in Europe, Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-821980-6

- Wettstein, Howard. Diasporas and Exiles: Varieties of Jewish Identity, University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0-520-22864-2

External links

- Ashkenazi history at the Jewish Virtual Library

- A Mosaic of a People: The Jewish Story and a Reassessment of the DNA Evidence by Ellen Levy-Coffman

- "The Matrilineal Ancestry of Ashkenazi Jewry: Portrait of a Recent Founder Event" (PDF)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.