Difference between revisions of "Apache" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

The Apachean tribes were historically very powerful, constantly at enmity with the [[Spain|Spaniards]] and Mexicans for centuries. The first Apache raids on [[Sonora]] appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. The [[United States Army|U.S. Army]], in their various confrontations, found them to be fierce [[warrior]]s and skillful strategists.<ref>[http://www.epcc.edu/nwlibrary/borderlands/18_apache.htm Apache Indians Southwest]</ref> | The Apachean tribes were historically very powerful, constantly at enmity with the [[Spain|Spaniards]] and Mexicans for centuries. The first Apache raids on [[Sonora]] appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. The [[United States Army|U.S. Army]], in their various confrontations, found them to be fierce [[warrior]]s and skillful strategists.<ref>[http://www.epcc.edu/nwlibrary/borderlands/18_apache.htm Apache Indians Southwest]</ref> | ||

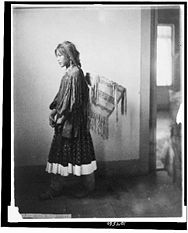

| − | + | [[Image:Kiowa Apache Essa-queta.jpg|thumb|200px|Essa-queta, Plains Apache chief]] | |

==Name== | ==Name== | ||

The word ''Apache'' entered [[English language|English]] via [[Spanish language|Spanish]], but the ultimate origin is uncertain. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests it was borrowed from the [[Zuni]] word ''apachu'' meaning "enemy" or the [[Yuma]] word for "fighting-men."<ref>[http://www.indians.org/welker/apache.htm Inde (Apache) Literature] Indians.org Retrieved July 23, 2008.</ref> The Apache native name has several versions including ''N'de'', ''Inde'', or ''Tinde'' ("the people").<ref name=waldman> Carl Waldman, ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744)</ref> | The word ''Apache'' entered [[English language|English]] via [[Spanish language|Spanish]], but the ultimate origin is uncertain. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests it was borrowed from the [[Zuni]] word ''apachu'' meaning "enemy" or the [[Yuma]] word for "fighting-men."<ref>[http://www.indians.org/welker/apache.htm Inde (Apache) Literature] Indians.org Retrieved July 23, 2008.</ref> The Apache native name has several versions including ''N'de'', ''Inde'', or ''Tinde'' ("the people").<ref name=waldman> Carl Waldman, ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:55, 24 July 2008

| Apache | |

|---|---|

| Total population | 31,000+ |

| Regions with significant populations | Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma |

| Language | Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Plains Apache, Mescalero, Western Apache |

| Religion | Shamanism, Christianity |

Apache is the collective name for several culturally related groups of Native Americans in the United States.

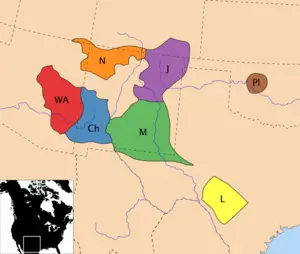

These indigenous peoples of North America speak a Southern Athabaskan (Apachean) language, and are related linguistically to the Athabaskan speakers of Alaska and western Canada. The modern term Apache excludes the related Navajo people. However, the Navajo and the other Apache groups are clearly related through culture and language and thus are considered Apachean. Apachean peoples formerly ranged over eastern Arizona, northwestern Mexico, New Mexico, and parts of Texas and the Great Plains.

There was little political unity among the Apachean groups. The groups spoke seven different languages. The current division of Apachean groups includes the Navajo, Western Apache, Chiricahua, Mescalero, Jicarilla, Lipan, and Plains Apache (formerly Kiowa-Apache). Apache groups are now in Oklahoma and Texas and on reservations in Arizona and New Mexico. Many Navajo reside on a 16-million acre reservation in the Four Corners region of the United States. Some Apacheans have moved to large metropolitan areas, such as New York City.

The Apachean tribes were historically very powerful, constantly at enmity with the Spaniards and Mexicans for centuries. The first Apache raids on Sonora appear to have taken place during the late 17th century. The U.S. Army, in their various confrontations, found them to be fierce warriors and skillful strategists.[1]

Name

The word Apache entered English via Spanish, but the ultimate origin is uncertain. The most widely accepted origin theory suggests it was borrowed from the Zuni word apachu meaning "enemy" or the Yuma word for "fighting-men."[2] The Apache native name has several versions including N'de, Inde, or Tinde ("the people").[3]

Language

Apachean peoples speak one or more of seven Southern Athabascan languages, which have relatively similar grammatical structures and sound systems. Southern Athabascan (or Apachean) is sub-family of the larger Athabascan family, which is a branch of Nadene.

Navajo is notable for being the indigenous language of the United States with the largest number of native speakers. However, all Apachean languages are endangered, including even Navajo. Lipan is reported extinct.

History

The Apache and Navajo tribal groups speak related languages of the language family referred to as Athabaskan, suggesting that they were once a single ethnic group. Other Athabaskan-speaking people in North America reside in an area from Alaska through west-central Canada, and some groups can be found along the Northwest Pacific Coast.

The Apache homeland is in the Southwest of the United States, an area that spreads across much of New Mexico and Arizona, as well as west Texas, south Colorado, western Oklahoma, south Kansas, and into northern Mexico.[3]

Entry into the Southwest

Archaeological and historical evidence suggest the Southern Athabaskan entry into the American Southwest sometime after 1000 C.E. Their nomadic way of life complicates accurate dating, primarily because they constructed less-substantial dwellings than other Southwestern groups.[4] They also left behind a more austere set of tools and material goods. Other Athabaskan speakers, perhaps including the Southern Athabaskan, adapted many of their neighbors' technology and practices in their own cultures.

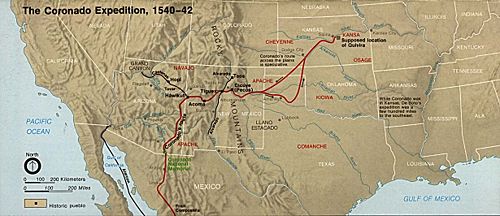

There are several hypotheses concerning Apachean migrations. One posits that they moved into the Southwest from the Great Plains. In the early sixteenth century, these mobile groups lived in tents, hunted bison and other game, and used dogs to pull travois loaded with their possessions. Substantial numbers and a wide range were recorded by the Spanish in the sixteenth century.

In April 1541, while traveling on the plains east of the Pueblo region, Francisco Coronado called them “dog nomads:”

After seventeen days of travel, I came upon a rancheria of the Indians who follow these cattle (bison). These natives are called Querechos. They do not cultivate the land, but eat raw meat and drink the blood of the cattle they kill. They dress in the skins of the cattle, with which all the people in this land clothe themselves, and they have very well-constructed tents, made with tanned and greased cowhides, in which they live and which they take along as they follow the cattle. They have dogs which they load to carry their tents, poles, and belongings.[5]

The Spaniards described Plains dogs as very white, with black spots, and “not much larger than water spaniels.” Plains dogs were slightly smaller than those used for hauling loads by modern northern Canadian peoples. Recent experiments show these dogs may have pulled loads up to 50 lb (20 kg) on long trips, at rates as high as two or three miles per hour (3 to 5 km/h).[6] This Plains migration theory associates Apachean peoples with the Dismal River aspect, an archaeological culture known primarily from ceramics and house remains, dated 1675-1725 excavated in Nebraska, eastern Colorado, and western Kansas.

Another theory posits migration south, through the Rocky Mountains, ultimately reaching the Southwest. Only the Plains Apache have any significant Plains cultural influence, while all tribes have distinct Athabaskan characteristics. Their presence on both the Plains and in the mountainous Southwest indicate that there were multiple early migration routes.

When the Spanish arrived in the area, trade between the Pueblo peoples and the Southern Athabaskans was well established. They reported the Pueblos exchanged maize and woven cotton goods for bison meat, hides and materials for stone tools. Coronado observed Plains people wintering near the Pueblos in established camps. Later Spanish sovereignty over the area disrupted trade between the Pueblos and the diverging Apache and Navajo groups. The Apache quickly acquired horses, improving their mobility for quick raids on settlements. In addition, the Pueblo were forced to work Spanish mission lands and care for mission flocks, thus they had fewer surplus goods to trade with their neighbors.[7]

Conflict with Mexico and the United States

In general, there seemed to be a pattern between the recently arrived Spanish who settled in villages and Apache bands over a few centuries. Both raided and traded with each other. Records of the period seem to indicate that relationships depended upon the specific villages and specific bands that were involved with each other. For example, one band might be friends with one village and raid another. When war happened between the two, the Spanish would send troops, after a battle both sides would "sign a treaty" and both sides would go home.

The traditional and sometimes treacherous relationships continued between the villages and bands with the independence of Mexico in 1821. By 1835 Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps but some bands were still trading with certain villages. When Juan José Compas, the leader of the Mimbreño Apaches, was killed for bounty money in 1837, Mangas Coloradas or Dasoda-hae (Red Sleeves) became principal chief and war leader and began a series of retaliatory raids against the Mexicans.

When the United States went to war against Mexico, many Apache bands promised U.S. soldiers safe passage through their lands. When the U.S. claimed former territories of Mexico in 1846, Mangas Coloradas signed a peace treaty, respecting them as conquerors of the Mexican's land. An uneasy peace (a centuries old tradition) between the Apache and the now citizens of the United States held until the 1850s, when an influx of gold miners into the Santa Rita Mountains led to conflict. This period is sometimes called the Apache Wars.

The United States' concept of a reservation had not been used by the Spanish, Mexicans or other Apache neighbors before. Reservations were often badly managed, and bands that had no kinship relationships were forced to live together. There were also no fences to keep people in or out. It was not uncommon for a band to be given permission to leave for a short period of time. Other times a band would leave without permission, to raid, return to their land to forage, or to simply get away. The military usually had forts nearby. Their job was keeping the various bands on the reservations by finding and returning those who left. The reservation policies of the United States kept various Apache bands leaving the reservations (at war) for almost another quarter century.

Most American histories of this era say the final defeat of an Apache band took place when 5,000 troops forced Geronimo's group of 30 to 50 men, women and children to surrender in 1886. This band and the Chiricahua scouts who tracked them were all sent to military confinement in Florida and, subsequently, Ft. Sill, Oklahoma.

Culture

The warfare between Apachean peoples and Euro-Americans has led to a stereotypical focus on certain aspects of Apachean cultures that are often distorted through misperception as noted by anthropologist Keith Basso:

Of the hundreds of peoples that lived and flourished in native North America, few have been so consistently misrepresented as the Apacheans of Arizona and New Mexico. Glorified by novelists, sensationalized by historians, and distorted beyond credulity by commercial film makers, the popular image of 'the Apache'—a brutish, terrifying semihuman bent upon wanton death and destruction—is almost entirely a product of irresponsible caricature and exaggeration. Indeed, there can be little doubt that the Apache has been transformed from a native American into an American legend, the fanciful and fallacious creation of a non-Indian citizenry whose inability to recognize the massive treachery of ethnic and cultural stereotypes has been matched only by its willingness to sustain and inflate them.[8]

Social organization

All Apachean peoples lived in extended family units (or family clusters) that usually lived close together with each nuclear family in separate dwellings. An extended family generally consisted of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, their married daughters, their married daughters' husbands, and their married daughters' children. Thus, the extended family is connected through a lineage of women that live together (that is, matrilocal residence), into which men may enter upon marriage (leaving behind his parents' family). When a daughter was married, a new dwelling was built nearby for her and her husband. Among the Navajo, residence rights are ultimately derived from a head mother. Although the Western Apache usually practiced matrilocal residence, sometimes the eldest son chose to bring his wife to live with his parents after marriage. All tribes practiced sororate (in which a man married his wife's sister, usually after the wife is dead or has proven infertile) and levirate marriages (in which a woman marries one of her husband's brothers after her husband's death, if there were no children, in order to continue the line of the dead husband).

All Apachean men practiced varying degrees of avoidance of his wife's close relatives—often strictest between mother-in-law and son-in-law. The degree of avoidance differed in different Apachean groups. The most elaborate system was among the Chiricahua where men must use indirect polite speech toward and were not allowed to be within visual sight of his relatives that he was in an avoidance relationship with. His female Chiricahua relatives also did likewise to him.

Several extended families worked together as a local group, which carried out certain ceremonies, and economic and military activities. Political control was mostly present at the local group level. Local groups were headed by a chief, a male who had considerable influence over others in the group due to his effectiveness and reputation. The chief was the closest societal role to a leader in Apachean cultures. The office was not hereditary and often filled by members of different extended families. The chief's leadership was only as strong as he was evaluated to be—no group member was ever obliged to follow the chief. The Western Apache criteria for evaluating a good chief included: industriousness, generosity, impartiality, forbearance, conscientiousness, and eloquence in language.

Many Apachean peoples joined together several local groups into bands. Band organization was strongest among the Chiricahua and Western Apache, while in the Lipan and Mescalero it was weak.

On the larger level, the Western Apache organized bands into what Grenville Goodwin called groups.[9] He reported five groups for the Western Apache: Northern Tonto, Southern Tonto, Cibecue, San Carlos, and White Mountain. The Jicarilla grouped their bands into moieties perhaps influenced by northeastern Pueblos. Additionally the Western Apache and Navajo had a system of matrilineal clans that were organized further into phratries (perhaps influence by western Pueblos).

The notion of tribe in Apachean cultures is very weakly developed essentially being only a recognition "that one owed a modicum of hospitality to those of the same speech, dress, and customs."[10] The seven Apachean tribes had no political unity (despite such portrayals in common perception[11]) and often were enemies of each other—for example, the Lipan fought against the Mescalero just as with the Comanche.

Kinship systems

The Apachean tribes have two surprisingly different kinship term systems: a Chiricahua type and a Jicarilla type.[12] The Chiricahua type system is used by the Chiricahua, Mescalero, and Western Apache with the Western Apache differing slightly from the other two systems and having some shared similarities with the Navajo system.

The Jicarilla type, which is similar to the Dakota-Iroquois kinship systems, is used by the Jicarilla, Navajo, Lipan, and Plains Apache. The Navajo system is more divergent, having similarities with Chiricahua type system. The Lipan and Plains Apache systems are very similar.

The Apachean speaking peoples can be distinguishes into two broad groups which share kinship systems. Morris E. Opler divided the Southern Athapaskan kinship systems into two types, Chiricahua and Jicarilla. The three linguistic tribes considered herein, the Chiricahua, Mescalero and Western Apaches, share the kinship system classified as the Chiricahua, where it was first studied by Opler. The early or proto-Apachean system from which these derived was most probably matrilineal, matrilocal, and characterized by the sororate, sororal polygyny, the levirate, sister exchange and bi-lateral cross-cousin marriage.

In the Chiricahua system matrilineal marriage groups are organized by generations, with matrilineal relatives being important. Sororate, levirate and sororal polygyny was practiced. The Chiricahua kinship is bilateral and organized in generational terms. Except the parent-child terms, all terms are self-reciprocal. Parental siblings are distinguished by side but otherwise are classified together without regard for sex and with terms extended to their children. In ego's generation the two gender determined terms siblings, parallel cousins and cross-cousins are used reciprocally. Grandparent terms are extended to their siblings. Male relationship with a female sibling is restrained, yet very caring towards her offspring. In-law avoidance is common.[13]

- Chiricahua

Chiricahua has four different words for grandparent: -chú[14] "maternal grandmother," -tsúyé "maternal grandfather," -chʼiné "paternal grandmother," -nálé "paternal grandfather." Additionally, a grandparent's siblings are identified by the same word; thus, one's maternal grandmother, one's maternal grandmother's sisters, and one's maternal grandmother's brothers are all called -chú. Furthermore, the grandparent terms are reciprocal, that is, a grandparent will use the same term to refer to their grandchild in that relationship. For example, a person's maternal grandmother will be called -chú and that maternal grandmother will also call that person -chú as well (i.e. -chú means one's opposite-sex sibling's daughter's child).

Chiricahua cousins are not distinguished from siblings through kinship terms. Thus, the same word will refer to either a sibling or a cousin (there are not separate terms for parallel-cousin and cross-cousin). Additionally, the terms are used according to the sex of the speaker (unlike the English terms brother and sister): -kʼis "same-sex sibling or same-sex cousin," -´-ląh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite-sex cousin." This means if one is a male, then one's brother is called -kʼis and one's sister is called -´-ląh. If one is a female, then one's brother is called -´-ląh and one's sister is called -kʼis. Chiricahuas in a -´-ląh relationship observed great restraint and respect toward that relative; cousins (but not siblings) in a -´-ląh relationship may practice total avoidance.

Two different words are used for each parent according to sex: -mááʼ "mother," -taa "father." Likewise, there are two words for a parent's child according to sex: -yáchʼeʼ "daughter," -gheʼ "son."

A parent's siblings are classified together regardless of sex: -ghúyé "maternal aunt or uncle (mother's brother or sister)," -deedééʼ "paternal aunt or uncle (father's brother or sister)." These two terms are reciprocal like the grandparent/grandchild terms. Thus, -ghúyé also refers to one's opposite-sex sibling's son or daughter (that is, a person will call their maternal aunt -ghúyé and that aunt will call them -ghúyé in return).

- Jicarilla

Unlike the Chiricahua system, the Jicarilla have only two terms for grandparents according to sex: -chóó "grandmother," -tsóyéé "grandfather." There are no separate terms for maternal or paternal grandparents. The terms are also used of a grandparent's siblings according to sex. Thus, -chóó refers to one's grandmother or one's grandaunt (either maternal or paternal); -tsóyéé refers to one's grandfather or one's granduncle. These terms are not reciprocal. There is only a single word for grandchild (regardless of sex): -tsóyí̱í̱.

There are two terms for each parent. These terms also refer to that parent's same-sex sibling: -ʼnííh "mother or maternal aunt (mother's sister)," -kaʼéé "father or paternal uncle (father's brother)." Additionally, there are two terms for a parent's opposite-sex sibling depending on sex: -daʼá̱á̱ "maternal uncle (mother's brother)," -béjéé "paternal aunt (father's sister).

Two terms are used for same-sex and opposite-sex siblings. These terms are also used for parallel-cousins: -kʼisé "same-sex sibling or same-sex parallel cousin (i.e. same-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)," -´-láh "opposite-sex sibling or opposite parallel cousin (i.e. opposite-sex father's brother's child or mother's sister's child)." These two terms can also be used for cross-cousins. There are also three sibling terms based on the age relative to the speaker: -ndádéé "older sister," -´-naʼá̱á̱ "older brother," -shdá̱zha "younger sibling (i.e. younger sister or brother)." Additionally, there are separate words for cross-cousins: -zeedń "cross-cousin (either same-sex or opposite-sex of speaker)," -iłnaaʼaash "male cross-cousin" (only used by male speakers).

A parent's child is classified with their same-sex sibling's or same-sex cousin's child: -zhácheʼe "daughter, same-sex sibling's daughter, same-sex cousin's daughter," -gheʼ "son, same-sex sibling's son, same-sex cousin's son." There are different words for an opposite-sex sibling's child: -daʼá̱á̱ "opposite-sex sibling's daughter," -daʼ "opposite-sex sibling's son."

Housing

All people in the Apache tribe lived in one of three types of houses. The first of which is the teepee, for those who lived in the plains. Another type of housing is the wickiup, an eight-foot tall frame of wood held together with yucca fibers and covered in brush usually in the Apache groups in the highlands. If a family member lived in a wickiup and they died, the wickiup would be burned. The final housing is the hogan, an earthen structure in the desert area that was good for keeping cool in the hot weather of northern Mexico.

Below is a description of Chiricahua wickiups recorded by anthropologist Morris Opler:

The home in which the family lives is made by the women and is ordinarily a circular, dome-shaped brush dwelling, with the floor at ground level. It is seven feet high at the center and approximately eight feet in diameter. To build it, long fresh poles of oak or willow are driven into the ground or placed in holes made with a digging stick. These poles, which form the framework, are arranged at one-foot intervals and are bound together at the top with yucca-leaf strands. Over them a thatching of bundles of big bluestem grass or bear grass is tied, shingle style, with yucca strings. A smoke hole opens above a central fireplace. A hide, suspended at the entrance, is fixed on a cross-beam so that it may be swung forward or backward. The doorway may face in any direction. For waterproofing, pieces of hide are thrown over the outer hatching, and in rainy weather, if a fire is not needed, even the smoke hole is covered. In warm, dry weather much of the outer roofing is stripped off. It takes approximately three days to erect a sturdy dwelling of this type. These houses are ‘warm and comfortable, even though there is a big snow.’ The interior is lined with brush and grass beds over which robes are spread.[15]

The women were responsible for the construction and maintenance of the wickiup.

Food

Apachean peoples obtained food from four main sources:[16]

- hunting wild animals,

- gathering wild plants,

- growing domesticated plants, and

- interaction with neighboring peoples for livestock and agricultural products (through raiding or trading).

The Western Apache diet consisted of 35-40 percent meat and 60-65 percent plant foods.

As the different Apachean tribes lived in different environments, the particular types of foods eaten varied according to their respective environment.

Hunting

Hunting was done primarily by men, although there were sometimes exceptions depending on animal and culture (e.g. Lipan women could help in hunting rabbits and Chiricahua boys were also allowed to hunt rabbits).

Hunting often had elaborate preparations, such as fasting and religious rituals performed by medicine men (shamans) before and after the hunt. In Lipan culture, since deer were protected by Mountain Spirits, great care was taken in Mountain Spirit rituals in order to ensure smooth deer hunting. Also the slaughter of animals was performed following certain religious guidelines (many of which are recorded in religious stories) from prescribing how to cut the animals, what prayers to recite, and proper disposal of bones. A common practice among Southern Athabascan hunters was the distribution of successfully slaughtered game. For example, among the Mescalero a hunter was expected to share as much as one half of his kill with a fellow hunter and with needy persons back at the camp. Feelings of individuals concerning this practice spoke of social obligation and spontaneous generosity.

The most common hunting weapon before the introduction of European guns was the bow and arrow. Various hunting strategies were used. Some techniques involved using animal head masks worn as a disguise. Whistles were sometimes used to lure animals closer. Another technique was the relay method where hunters positioned at various points would chase the prey in turns in order to tire the animal. A similar method involved chasing the prey down a steep cliff.

Eating certain animals was taboo. Although different cultures had different taboos, some common examples of taboo animals included: bears, peccaries, turkeys, fish, snakes, insects, owls, and coyotes. An example of taboo differences: the black bear was a part of the Lipan diet (although not as common as buffalo, deer, or antelope), but the Jicarilla never ate bear because it was considered an evil animal. Some taboos were a regional phenomena, such as of eating fish, which was taboo throughout the southwest (e.g. in certain Pueblo cultures like the Hopi and Zuni) and considered to be snake-like (an evil animal) in physical appearance.[17][18]

Non-domesticated plants & other foodstuffs

The gathering of plants and other foodstuffs was primarily a female chore. However, in certain activities, such as the gathering of heavy agave crowns, men helped. Numerous plants were used for medicine and religious ceremonies in addition their nutrional usage. Other plants were utilized for only their religious or medicinal value.

The abundant agave (mescal) was used by all Apache, but was particularly important to the Mescalero[19], who gathered the crowns in late spring after reddish flower stalks appeared. The smaller sotol crowns were also important. Both crowns of both plants were baked and dried. The crowns (the tuberous base portion) of this plant (which were baked in large underground ovens and sun-dried) and also the shoots were used. They baked and dried agave crowns and then pounded them into pulp which they formed into rectangular cakes.

Crop cultivation

The different Apachean groups varied greatly with respect to growing domesticated plants. The Western Apache, Jicarilla, and Lipan practiced some crop cultivation. The Mescalero and one Chiricahua band practiced very little cultivation. The other two Chiricahua bands and the Plains Apache did not grow any crops.

Trading and raiding

Although not distinguished by Europeans or Euro-Americans, all Apachean tribes made clear distinctions between raiding (for profit) and war. Raiding was done with small parties with a specific economic target. Warfare was waged with large parties (often using clan members) with the sole purpose of retribution.

Religion

Apachean religious stories relate two culture heros (one of the sun/fire, Killer-Of-Enemies/Monster Slayer, and one of water/moon/thunder, Child-Of-The-Water/Born For Water) that destroy a number of creatures that are harmful to humankind. Another story is of a hidden ball game where good and evil animals decide whether or not the world should be forever dark. Coyote, the trickster, is an important being that usually has inappropriate behavior (such as marrying his own daughter). The Navajo, Western Apache, Jicarilla, and Lipan have an emergence story while this is lacking in the Chiricahua and Mescalero.[20]

Most Southern Athabascan “gods” are personified natural forces that run through the universe and are used for human purposes through ritual ceremonies. The following is a formulation by Basso for the Western Apache's concept of diyí’:

The term diyí’ refers to one or all of a set of abstract and invisible forces which are said to derive from certain classes of animals, plants, minerals, meteorological phenomena, and mythological figures within the Western Apache universe. Any of the various powers may be acquired by man and, if properly handled, used for a variety of purposes.[21]

These ceremonies were led by medicine men (shamans) although they could also be acquired by direct revelation to the individual. Different Apachean cultures had different views of ceremonial practice. Most Chiricahua and Mescalero ceremonies were learned by personal religious visions while the Jicarilla and Western Apache used standardized rituals as the more central ceremonial practice. Important standardized ceremonies include the puberty ceremony (sunrise dance) of young women, Navajo chants, Jicarilla long-life ceremonies, and Plains Apache sacred-bundle ceremonies.

Certain animals are considered spiritually evil and are prone to cause sickness: owls, snakes, bears, coyotes.

Many Apachean ceremonies use masked representations of religious spirits. Sandpainting is important to the Navajo, Western Apache, and Jicarilla. Both the use of masks and sandpainting are believed to be a product of cultural diffusion from neighboring Pueblo cultures.[22]

The Apaches participate in many spiritual dances including the rain dance, a harvest and crop dance, and a spirit dance. These dances were mostly for enriching their food resources.

Art

Costumes for dances.[3] Apache fiddle. The Apache name Tzii'edo' a 'tl means "wood that sings." It is a two-stringed bowed zither, made from a hollowed agave stalk. As it is the only Native American bowed instrument, it remains unclear whether it is indigenous or of European derivation.[23] Not much pottery, baskets.[3]

Contemporary Apache

The present-day Apache groups include the Jicarilla and Mescalero of New Mexico, the Chiricahua of the Arizona-New Mexico border area, the Western Apache of Arizona, the Lipan Apache of southwestern Texas, and the Plains Apache of Oklahoma. There undoubtedly existed other Apache groups which are not as well-known by modern anthropologists and historians.

Western Apaches are the only Apache group that remains within Arizona. The group is divided into several reservations that crosscut cultural divisions. The Western Apache reservations include the Fort Apache White Mountain, San Carlos, Yavapai-Apache, Tonto-Apache, and Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache reservations. There are also Apaches on the Yavapai-Prescott reservation and off-reservation in Arizona and throughout the United States. The White Mountain Apache Tribe is located in the east central region of Arizona, 194 miles (312 km) northeast of Phoenix. The Tonto Apache Reservation was created in 1972 near Payson in eastern Arizona. Within the Tonto National Forest northeast of Phoenix it consists of 85 acres (344,000 m²) and serves about 100 tribal members. The tribe operates a casino. The Yavapai-Apache Nation Reservation southwest of Flagstaff, Arizona, is shared with the Yavapai. There is a visitor center in Camp Verde, Arizona, and at the end of February an Exodus Days celebration is held with a historic re-enactment and a pow-wow.

The Chiricahua were divided into two groups after they were released from being prisoners of war. The majority moved to the Mescalero Reservation and are now subsumed under the larger Mescalero political group along with the Lipan. The other Chiricahuas remained in Oklahoma and eventually formed the Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma.

The Mescalero are located on the Mescalero Reservation in southeastern New Mexico, near historic Fort Stanton.

The Jicarilla are located on the Jicarilla Reservation in Rio Arriba and Sandoval counties in northwestern New Mexico. The Lipan, now few in number, are located primarily on the Mescalero Reservation. Other Lipans live in Texas. Plains Apaches are located in Oklahoma concentrated around Anadarko.

Notable Apache

- Cochise, Apache Chief

- Mangus Coloradas, Apache Chief

- Loco, Apache Chief

- Taza, Apache Chief

- Nana, Apache Chief

- Mangus, Apache Chief

- Chihuahua, Apache Chief

- Geronimo, Apache Leader

- Naiche, Apache Chief

- Victorio, Apache Chief

- Chatto, Apache Scout

- Jay Tavare, actor

- Raoul Trujillo, dancer, choreographer, actor

Notes

- ↑ Apache Indians Southwest

- ↑ Inde (Apache) Literature Indians.org Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744)

- ↑ Cordell, p. 148

- ↑ Hammond and Rey

- ↑ Henderson

- ↑ Cordell, p.151

- ↑ Basso, p. 462

- ↑ Grenville Goodwin, The Social Organization of the Western Apache (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1969, ISBN 0816501947)

- ↑ Opler 1983a, p.369

- ↑ Basso 1983

- ↑ Opler 1936b

- ↑ James Q. Jacobs Post-Contact Social Organization of Three Apache Tribes (1999) Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ↑ All kinship terms in Apachean languages are inherently possessed, which means they must be preceded by a possessive prefix. This is signified by the preceding hyphen.

- ↑ Opler, 1941, pp.22-23, 385-386

- ↑ Information on Apache subsistence are in Basso (1983: 467-470), Foster & McCollough (2001: 928-929), Opler (1936b: 205-210; 1941: 316-336, 354-375; 1983b: 412-413; 1983c: 431-432; 2001: 945-947), and Tiller (1983: 441-442).

- ↑ Brugge, p.494

- ↑ Landar

- ↑ The name Mescalero is, in fact, derived from the word mescal, a reference to their use of this plant as food.

- ↑ Opler 1983a, pp.368-369

- ↑ Basso, 1969, p.30

- ↑ Opler 1983a, pp.372-373

- ↑ Tzii'edo' a 'tl (Apache Fiddle) Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

Bibliography

- Basso, Keith H. Western Apache witchcraft (Anthropological papers). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1969. ISBN 0816501424

- Brugge, David M. Navajos in the Catholic Church Records of New Mexico 1694 - 1875. Navajo Community College Press, 1986. ISBN 0912586591

- Cordell, Linda S. Ancient Pueblo Peoples. St. Remy Press and Smithsonian Institution, 1994. ISBN 0895990385.

- DeMallie, Raymond, and William Sturtevant (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians: Plains Vol. 13. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2001. ISBN 0160504007

- Etulain, Richard W. New Mexican Lives: A Biographical History. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2002. ISBN 0826324339

- Goodwin, Grenville. The Social Organization of the Western Apache. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1969 (original 1941). ISBN 0816501947

- Haley, James L. Apaches: A History and Culture Portrait. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997. ISBN 0806129786

- Hammond, George P., and Agapito Rey (eds.). Narratives of the Coronado Expedition 1540-1542. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1940.

- Henderson, Richard. "Replicating Dog Travois Travel on the Northern Plains." Plains Anthropologist 39 (1994): 145-59.

- Hodge, F. W. (ed.). Handbook of American Indians. Washington, DC, 1907.

- Jacobs, James Q. Post-Contact Social Organization of Three Apache Tribes, 1999. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Krauss, Michael E. (1973). Na-Dene. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Linguistics in North America (pp. 903-978). Current trends in linguistics (Vol. 10). The Hague: Mouton. (Reprinted 1976).

- Landar, Herbert J. (1960). The loss of Athapaskan words for fish in the Southwest. International Journal of American Linguistics, 26 (1), 75-77.

- Opler, Morris E. (1936). The kinship systems of the Southern Athapaskan-speaking tribes. American Anthropologist, 38 (4), 620-633.

- Opler, Morris E. (1941). An Apache life-way: The economic, social, and religious institutions of the Chiricahua Indians. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Ortiz, Alfonso (ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volume 10, Southwest. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1983.

- Sweeney, Edwin R. (1998). Mangas Coloradas: Chief of the Chiricahua Apaches. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3063-6

- Terrell, John Upton. (1972). Apache chronicle. World Publishing. ISBN 0-529-04520-6.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

- Fort Sill Apache Tribal Chairman Jeff Houser's Website

- Tonto Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- Yavapai-Apache Nation (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- White Mountain Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- San Carlos Apache Tribe (Arizona Intertribal Council)

- Official Yavapai-Apache Nation website

- Post-Contact Social Organization of Three Apache Tribes

- Apache Indians Defended Homelands in Southwest

- Sonora: Four centuries of indigenous resistance

- Indians of Arizona (from History of Arizona)

- The Apache (from History of Arizona)

- Apache myths & texts

- Grenville Goodwin's preface to Myths and Tales of the White Mountain Apache

- Inde (Apache) Literature

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.