| Zuni |

|---|

| Total population |

| 12,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (New Mexico) |

| Languages |

| Zuni, English |

| Religions |

| Christianity (incl. syncretist forms), Zuni religion |

The Zuni (also spelled Zuñi) or Ashiwi are a Native American tribe, one of the Pueblo peoples, most of whom live in the Pueblo of Zuñi on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico. Zuñi is 55 km (35 miles) south of Gallup, New Mexico and has a population of about 12,000, with over 80 percent being Native Americans, with 43.0 percent of the population below the poverty line as defined by the U.S. income standards. However, many of the people do not consider their low income and lifestyle to be poverty.[1]

Before the Spanish colonization and missionaries, the Zuni lived peacefully like other Pueblo Indians, farming supplemented by hunting and fishing, in harmony with nature. Their religious beliefs guided their way of life and involved numerous ceremonies and significant rite of passage. Thus, they resisted strongly the attempts of Jesuits to convert them to Christianity. Today, Zuni remain famous for their artistry. They continue to make pottery and jewelry in traditional styles, many of them supporting their families through this work. They also continue to practice their traditional ceremonies and dances, many of which they now perform for tourists.

History

The Zuni, like other Pueblo peoples, are believed to be the descendants of the Ancient Pueblo Peoples who lived in the deserts of New Mexico, Arizona, Southern Colorado and Utah for centuries. Archaeological evidence shows they have lived in their present location for about 1,300 years.

The Hawikuh Pueblo was the first pueblo seen by the Spanish explorers. It was one of the legendary Seven Cities of Cibola, rumored to be filled with great riches, sought by Francisco Coronado. The black scout Estevanico was the first non-Native to reach this area. When the Spanish defeated the Zuni, they discovered Hawikuh to be an ordinary pueblo, without gold or great wealth.

The first Spanish mission in Zuni territory was established in Hawikuh in 1629. The missionaries were for the most part unable to win converts among the Zuni. The Zuni attacked and killed the missionaries in 1632, and raids by Apache in 1672 forced the abandonment of the mission.

Before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Zuni lived in six different villages. After the revolt, until 1692, they took refuge in a defensible position atop Dowa Yalanne, a steep mesa five km (two miles) southeast of the present Pueblo of Zuñi. Dowa meaning "corn," and Yalanne meaning "mountain." After the establishment of peace and the return of the Spanish, the Zuni relocated in their present location, only briefly returning to the mesa top in 1703.

Culture

Zuni language

Zuni traditionally speak the Zuni language, a unique language which is unrelated to the languages of the other Pueblo peoples. Zuni (also Zuñi or Shiwi) is a language originating in North America. It is spoken by around 10,000 people worldwide, especially in New Mexico and much smaller numbers in parts of Arizona. Its speakers are known as the Zuni (Ashiwi).

Zuni is now generally considered a language isolate. Some linguists have categorized it as a Penutian language, and Bertha Dutton suggested that according to the Swadesh list, "If the Zuni language is a member of the Penutian language family, then it is a distant relative of the Tanoan languages (Tewi)."[2]

The Penutian Hypothesis was advanced by Alfred Kroeber and Roland B. Dixon and later refined by Edward Sapir, in an attempt to reduce the number of unrelated language families in the culturally diverse area centered in California's central coast. While this theory was plausible for some of the languages, the problem of verification of this theory was that to find any evidence of any cognates between the California languages and Zuni, one would possibly have to trace the languages' lineage by as much as 3,000-5,000 years or more.

In a speculative work The Zuni Enigma, Nancy Yaw Davis has offered a controversial comparative of cognates between the Zuni language and another language isolate, the Japanese language.[3]

Zuni world view

The Zuni worldview may properly be considered as a study in orthology. The form and function of design images and pictographic rock art images and their interpretation according to Zuni mythology or cosmology sufficed as a form of communication prior to the appearance of a written language.

Frank Hamilton Cushing, a pioneering anthropologist associated with the Smithsonian Institution, lived with the Zuni from 1879 to 1884. He became a member of the Zuni's Priesthood of the Bow during his tenure at the Pueblo. He studied their daily lives, material culture, and was able to obtain insight into their secret religious ceremonies.

Beliefs

Life for these agricultural people revolves around their religious beliefs. They have a cycle of religious ceremonies which takes precedence over all else. Their religious beliefs are centered on the three most powerful of their deities – Earth Mother, Sun Father, and Moonlight-Giving Mother. The Sun is especially worshiped. In fact the Zuni words for daylight and life are the same word. The Sun is therefore, seen as the giver of life.

Each person's life is marked by important ceremonies to celebrate their coming to certain milestones in their existence. Birth, coming of age, marriage, and death are especially celebrated.

Zuni make a barefoot religious pilgrimage every four years on the Barefoot Trail to Kolhu/wala:wa, also called Zuni Heaven or Kachina Village; a 12,482-acre detached portion of the Zuni Reservation about 60 miles Southwest of Zuni Pueblo. The four-day observance occurs around the summer solstice, practiced for many hundreds of years and is well known to local residents.

Another barefoot pilgrimage conducted annually for centuries by the Zuni and other southwestern tribes is made to Zuni Salt Lake for the harvesting of salt during the dry months, and for religious purposes. The lake is home to the Salt Mother, Ma'l Oyattsik'i and is led to by several ancient Pueblo roads and trails.

The coming of age rite of passage is celebrated differently by boys and girls. A girl who is ready to declare herself as a maiden will go to the home of her father's mother early in the morning and grind corn all day long. Corn is a sacred food and a staple in the diet of the Zuni. The girl is, therefore, declaring that she is ready to play a role in the welfare of her people. When it is time for a boy to become a man he will be taken under the wing of a spiritual 'father', selected by the parents. This one will instruct the boy through the ceremony to follow. The boy will go through certain initiation rites to enter one of the men's societies. He will learn how to take on either religious, secular, or political duties within that order.

The Zuni is one of the clown societies of the Pueblo Indians; one is initiated into the Zuni Ne'wekwe order by a ritual of filth-eating similar to Eucharist. "Mud and excrement are smeared on the body for the clown performance, and parts of the performance may consist of sporting with excreta, smearing and daubing it, or drinking urine and pouring it on one another".[4][5]

According to Zuni mythology, the first humans came from four caves in the underworld. The Earth was a dangerous place, covered with water and monsters. The children of the sun took pity on humankind and hardened earth with lightning, then turned many animals into stone, leaving only the modern ones.

Amitolane is a rainbow spirit. Apoyan Tachu and Awitelin Tsita are the Sun Father and Earth Mother and the parents of all life on Earth. Awonawilona is the creator god, who made the clouds and ocean, which was covered with green algae that hardened, split and became Awitelin Tsita and Apoyan Tachu. Kokopelli is a spirit revered or worshiped in many southwestern tribes. He is a whimsical humpbacked flutist, considered to be the spirit of music. He represents a rain god or fertility symbol for the Zuni and was also known as Ololowishkya. He frequently appeared with Paiyatamu, another flutist, in maize grinding ceremonies. Ma'l Oyattsik'i is the Salt Mother. Annual barefoot pilgrimages have been made for centuries on the trail to her home, the Zuni Salt Lake. Uhepono is a hairy giant that lived in the underworld; it has huge eyes and human limbs. Yanauluha is a hero, who brought agriculture, medicine, and all the customs of the Zuni people.

As do other Pueblo cultures, the Zuni believe in Kachinas, supernatural beings who represent and have charge over various aspects of the natural world. There are literally hundreds of different Kachinas, which may represent anything from rain to watermelon, various animals, stars, and even other Indian tribes. The Zuni believe that the Kachinas live in the Lake of the Dead, a mythical lake which is reached through Listening Spring Lake located at the junction of the Zuni River and the Little Colorado River.

Zuni crafts

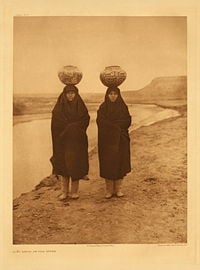

In the earlier days of that age when Zuni roamed an area that is now the Southwestern United States, they made pottery for food and water storage. Women made pottery according to the clan's tradition of functionality and design. Clay for the pottery is sourced locally and thanks is given to the Earth Mother Awitelin Tsita according to ritual prior to extraction. It is prepared first by grinding, and then sifting and mixing with water. After the clay is shaped into a vessel or ornament, it will be scraped smooth with a scraper. Then a thin layer of finer clay will be applied to the surface for extra smoothness. Next the vessel will be polished with a stone. Then the piece is painted with home-made organic dyes using a traditional yucca brush. The function of the ware is determined by its shape, and its design and painted images. To fire the pottery the Zuni used sheep dung in traditional kilns which had not changed for hundreds of years. However, most contemporary Zuni pottery is now fired in modern, electric kilns. While the firing of the pottery was usually a community enterprise, silence or communication in low voices was essential in order to maintain the original "voice" of the "being" of the clay and the purpose of the end product.[6] The selling of pottery and other traditional arts and crafts is a major source of income for many of the Zuni, and an artisan may be the sole financial support for their immediate family as well as others. They made pottery, clothing, baskets, and Kachina dolls.

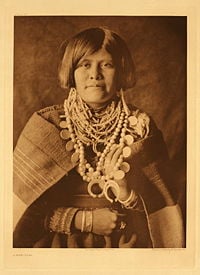

They also make fetish carvings and necklaces for the purpose of ritual and trade, and more recently for sale to their avid collectors. The art of silversmithing was introduced to the Zuni by Anglo vendors and trading posts, soon after being introduced to the Navajo towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Contemporary Zuni

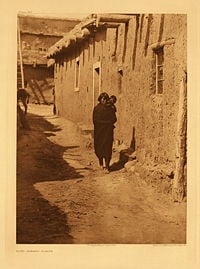

The Zuni were and are a peaceful, deeply traditional people who lived by irrigated agriculture and now by the sale of traditional crafts. Some Zuni still live in the old style Pueblos, while others live in modern flat-roofed houses made from adobe and concrete block. Their location is relatively isolated, but they welcome respectful tourists.

Many Zuni also became master silversmiths and perfected the skill of stone inlay. They found that by using small pieces of stone they were able to create intricate designs and unique patterns. Small oval-shaped stones with pointed ends are set close to one another and side by side. The technique is normally used with turquoise often combined with other semiprecious stones, in creating necklaces or rings. Carved stone animal fetishes, jewelry, needlepoint, and pottery are popular items. The bear, coyote, eagle and turtle are commonly used as motifs.

Another technique they have mastered is needlepoint.

The Zuni continue to practice their traditional religion with its regular ceremonies and dances and an independent mythology.

The Zuni Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Zuni tribe. It lies in the Zuni River valley and is located primarily in Cibola and McKinley counties in western New Mexico, about 150 miles west of Albuquerque. There are also several smaller non-contiguous sections in Apache County, Arizona, northwest of the city of St. Johns. The main part of the reservation borders the state of Arizona to the west and the Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation to the east. The main reservation is also surrounded by the Painted Cliffs, the Zuni Mountains and the Cibola National Forest. The reservation's total land area is 1,873.45 km² (723.343 sq mi). The population was reported at 7,758 inhabitants in the 2000 census.

The Zuni Tribe also has land holdings in Catron County, New Mexico and Apache County, Arizona, which do not border the main reservation.

Also on the main reservation are the Hawikuh Ruins. The ancient Zuni pueblo of Hawikuh was the largest of the Seven Cities of Cibola. It was established in the 1200s and abandoned in 1680.

The largest town on the reservation is Zuni Pueblo, which is seat of Tribal government. Also on the reservation are the small towns of Black Rock and Pescado. There is a branch campus of the University of New Mexico located in Zuni.

The Zuni Tribe is governed by an elected governor, lieutenant governor, and a six member Tribal Council with elections being held every four years. The governor is the administrative head of the Tribal Council, which is the final decision-making body on the reservation. The council oversees finances, business decisions, taxes, and contracts.

The Zuni Tribal Fair and Rodeo is held the third weekend in August. The Zuni participate in the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremony.

There is an old Spanish mission, Our Lady of Guadalupe Mission, which is a popular attraction; and a tribal museum.

Zuni in popular culture

- People living the Zuni way play a role in Brave New World (1932), a novel by Aldous Huxley.

- Zuni culture plays a prominent role in the 1973 novel Dance Hall of the Dead, by the American writer Tony Hillerman, who has written many novels (Joe Leaphorn series) and mysteries (The Jim Chee series) on the theme, which has been made into dramas for television, including Coyote Waits.

Notes

- ↑ Pueblo Of Zuni www.ashiwi.org. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ↑ Bertha P. Dutton. American Indians of the Southwest. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1983).

- ↑ Nancy Yaw Davis. The Zuni Enigma. "A Native American People's Possible Japanese Connection." www.wwnorton.com. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ Elsie Clews Parsons and Ralph L. Beals, "The Sacred Clowns of the Pueblo and Mayo-Yaqui Indians," American Anthropologist 36 (October-December 1934): 493

- ↑ M. Conrad Hyers. 1996. The Spirituality of Comedy: comic heroism in a tragic world. (Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers), 145

- ↑ For descriptions of the Zuni pottery making process see: Ruth L. Bunzel. The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art. (New York: Dover, 1929), and, Zuni: Selected Writings of Frank Hamilton Cushing, ed. by Jesse Green. (Lincoln, NE: and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1979).

References and Bibliography

- Baxter, Sylvestor and Frank H. Cushing. 1999. My Adventurers in Zuni: Including Father of The Pueblos & An Aboriginal Pilgrimage. Filter Press, LLC. ISBN 0865410453

- Benedict, Ruth. 1969. Zuni Mythology, in 2 vols. (original 1935) Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, no. 21. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Bunzel, Ruth Leah. 1932. "Introduction to Zuni Ceremonialism" (1932a); "Zuni Origin Myths" (1932b); "Zuni Ritual Poetry" (1932c) in Forty-Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Reprint, Zuni Ceremonialism: Three Studies. Introduction by Nancy Pareto. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, (original 1932) 1992.

- __________. The Pueblo potter; A study of creative imagination in primitive art, AMS Press. 1969. ASIN: B0006C9WFQ

- __________. "Zuni Katcinas: An Analytic Study." (1932d). Forty-Seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 836-1086. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1932. Reprint, Zuni Katcinas: 47th Annual Report. Albuquerque, NM: Rio Grande Classics, 1984.

- __________. Zuni Texts. Publications of the American Ethnological Society, 15. New York, NY: G.E. Steckert & Co., 1933.

- Cushing, Frank Hamilton and Barton Wright. The mythic world of the Zuni. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1992. ISBN 0826310362

- __________. Outlines of Zuni Creation Myths. AMS Press, Reprint edition (June 1, 1996). ISBN 0404118348

- __________. Zuni Coyote Tales. University of Arizona Press, 1998. ISBN 0816518920

- __________. Zuni Fetishes, designed by K. C. DenDooven, photographed by Bruce Hucko, Annotations by Mark Bahti, KC Publications, 1999. ISBN 0887141447

- __________. Zuni Folk Tales. University of Arizona Press, 1999. ISBN 0816509867

- __________. Zuni: Selected Writings of Frank Hamilton Cushing, edited by Jesse Green, foreword by Fred Eggan, Introduction by Jesse Green. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1978. ISBN 0803221002

- __________. Zuni Breadstuff. (Indian Notes and Monographs, Vol. 8.), AMS Press, 1975. ISBN 0404118356

- Davis, Nancy Yaw. 2001. The Zuni Enigma. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001. ISBN 0393322300

- Dutton, Bertha P. 1983. American Indians of the Southwest. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826307040

- Eggan, Fred and T.N. Pandey. "Zuni History, 1855-1970." Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest, Vol. 9. Ed. By Alfonso Ortiz. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1979.

- Green, Jesse, Sharon Weiner Green and Frank Hamilton Cushing. 1990. Cushing at Zuni: The Correspondence and Journals of Frank Hamilton Cushing, 1879-1884. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826311725

- Hyers, M. Conrad. 1996. The Spirituality of Comedy: comic heroism in a tragic world. Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1560002182

- Newman, Stanley. Zuni Dictionary. Indiana University Research Center Publication Six. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, 1958.

- Parsons, Elsie Clews and Ralph L. Beals, "The Sacred Clowns of the Pueblo and Mayo-Yaqui Indians," American Anthropologist 36 (October-December 1934): 493

- Preucel, Robert W. 2002. Archaeologies of the Pueblo Revolt: Identity, Meaning, and Renewal in the Pueblo World. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826322476

- Roberts, John. 1961. "The Zuni," in In Variations in Value Orientations, ed. by F.R. Kluckhorn and F.L. Strodbeck. Evanston, IL: and Elmsford, NY: Row, Peterson, 285-316.

- Smith, Watson and John Roberts. 1954. Zuni Law: A Field of Values. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Vol. 43. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

- Tedlock, Barbara. 1992. The Beautiful and the Dangerous: Dialogues with the Zuni Indians. New York, NY: Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0670844487

- Tedlock, Dennis. 1978. Finding the Center: Narrative Poetry of the Zuni Indians. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803294004

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Young, M. Jane. 1988. Signs from the Ancestors: Zuni Cultural Symbolism and Perceptions in Rock Art. Albuquerque, NY: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826312037

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- The Religious Life of the Zuñi Child by (Mrs.) Tilly E. (Matilda Coxe Evans) Stevenson, from Project Gutenberg

- Zuni Handcrafted Jewelry Information

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.