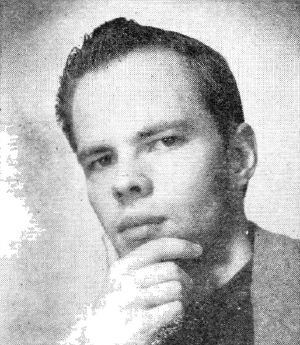

Philip K. Dick

| Philip K. Dick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 16 1928 Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Died | March 2 1982 (aged 53) Santa Ana, California, U.S. |

| Pen name | Richard Philips Jack Dowland Horselover Fat PKD |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, short story writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Genres | Science Fiction Speculative Fiction Postmodernism |

| Influences | Flaubert, Balzac, Kant, Marcel Proust, Carl Jung, Samuel Beckett, Dostoyevsky, John Sladek, Nathanael West, Jorge Luis Borges, Jack Spicer |

| Influenced | The Wachowski Brothers, Jean Baudrillard, David Cronenberg, Richard Linklater, Jonathan Lethem, Fredric Jameson, Slavoj _i_ek, Roberto Bolaño, Rodrigo Fresán, Mark E. Smith |

Philip Kindred Dick (December 16, 1928 – March 2, 1982) was an American science fiction novelist and short story writer. Dick explored sociological, political and metaphysical themes in novels dominated by monopolistic corporations, authoritarian governments, and altered states. In his later works, Dick's thematic focus strongly reflected his personal interest in metaphysics and theology.

He often drew upon his own life experiences and addressed the nature of drug use, paranoia and schizophrenia, and mystical experiences in novels such as A Scanner Darkly and VALIS. While his interest lay in metaphysical issues, his sympathy always lay with the quiet dignity of the common man facing the difficult challenges of everyday life.

The novel The Man in the High Castle bridged the genres of alternate history and science fiction, earning Dick a Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1963. Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, a novel about a celebrity who awakens in a parallel universe where he is unknown, won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for best novel in 1975.

Life

Philip Kindred Dick and his twin sister, Jane Charlotte Dick, were born six weeks premature to Dorothy Kindred Dick and Joseph Edgar Dick in Chicago. Dick's father, a fraud investigator for the United States Department of Agriculture, had recently taken out life insurance policies on the family. An insurance nurse was dispatched to the Dick household. Upon seeing the malnourished Philip and injured Jane, the nurse rushed the babies to hospital. Baby Jane died en route, just five weeks after her birth (January 26, 1929). The death of Philip's twin sister profoundly affected his writing, relationships, and every aspect of his life, leading to the recurrent motif of the "phantom twin" in many of his books.

The family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. When Philip turned five, his father was transferred to Reno, Nevada. Dorothy refused to move, and she and Joseph were divorced. Joseph fought her for custody of Philip but did not win the case. Dorothy, determined to raise Philip alone, took a job in Washington, D.C. and moved there with her son. Philip was enrolled at John Eaton Elementary School from 1936 to 1938, completing the second through the fourth grades. His lowest grade was a "C" in written composition, although a teacher remarked that he "shows interest and ability in story telling." In June 1938, Dorothy and Philip returned to California.

Dick attended Berkeley High School in Berkeley, California. He and Ursula K. Le Guin were members of the same high school graduating class (1947), yet were unacquainted at the time. After graduating from high school he briefly attended the University of California, Berkeley as a German major, but dropped out before completing any coursework. At Berkeley, Dick befriended poets Robert Duncan and poet and linguist Jack Spicer, who gave Dick ideas for a Martian language. Dick claimed to have been host of a classical music program on KSMO Radio in 1947.[1] From 1948 to 1952 he worked in a record store. In 1955, Dick and his second wife, Kleo Apostolides, received a visit from the FBI. They believed this resulted from Kleo's socialist views and left-wing activities. The couple briefly befriended one of the FBI agents.[1]

In his boyhood, around the age of 13, Dick had a recurring dream for several weeks. He dreamed he was in a bookstore, trying to find an issue of Astounding Magazine. This issue of the magazine would contain the story titled "The Empire Never Ended," which would reveal the secrets of the universe to him. As the dream recurred, the pile of magazines he searched grew smaller and smaller, but he never reached the bottom. Eventually, he became anxious that discovering the magazine would drive him mad (as in Lovecraft's Necronomicon or Chambers' The King in Yellow, promising insanity to the reader). Shortly thereafter, the dreams ceased, but the phrase "The Empire Never Ended" would appear later in his work. Dick was a voracious reader of religion, philosophy, metaphysics and Gnosticism, ideas of which appear in many of his stories and visions.

On February 20, 1974, Dick was recovering from the effects of sodium pentothal administered for the extraction of an impacted wisdom tooth. Answering the door to receive delivery of extra analgesic, he noticed that the delivery woman was wearing a pendant with a symbol that he called the "vesicle pisces." This name seems to have been based on his confusion of two related symbols, the ichthys (two intersecting arcs delineating a fish in profile) that early Christians used as a secret symbol, and the vesica piscis. After the delivery woman's departure, Dick began experiencing strange visions. Although they may have been initially attributable to the medication, after weeks of visions he considered this explanation implausible. "I experienced an invasion of my mind by a transcendentally rational mind, as if I had been insane all my life and suddenly I had become sane," Dick told Charles Platt.[2]

Throughout February and March 1974, he experienced a series of visions, which he referred to as "two-three-seventy four" (2-3-74), shorthand for February-March 1974. He described the initial visions as laser beams and geometric patterns, and, occasionally, brief pictures of Jesus and of ancient Rome. As the visions increased in length and frequency, Dick claimed he began to live a double life, one as himself, "Philip K. Dick," and one as "Thomas," a Christian persecuted by Romans in the first century C.E. Despite his history of drug use and elevated stroke risk, Dick began seeking other rationalist and religious explanations for these experiences. He referred to the "transcendentally rational mind" as "Zebra," "God" and, most often, "VALIS." Dick wrote about the experiences in the semi-autobiographical novels VALIS and Radio Free Albemuth.

In time, Dick became paranoid, imagining plots against him by the KGB and FBI. At one point, he alleged they were responsible for a burglary of his house, from which documents were stolen. He later came to suspect that he might have committed the burglary against himself, and then forgotten he had done so. Dick speculated that he may have suffered from schizophrenia.

Dick married five times, and had two daughters and a son; each marriage ended in divorce.

- May 1948, to Jeanette Marlin – lasted six months

- June 1950, to Kleo Apostolides – divorced 1959

- 1959, to Anne Williams Rubinstein – divorced 1964

- child: Laura Archer, born February 25, 1960

- 1966, to Nancy Hackett – divorced 1972

- child: Isolde, "Isa," born 1967

- April 18, 1973, to Leslie (Tessa) Busby – divorced 1977

- child: Christopher, born 1973

Philip K. Dick died in Santa Ana, California, on March 2, 1982. He had suffered a stroke five days earlier, and was disconnected from life support after his EEG had been consistently isoelectric since losing consciousness. After his death, his father Edgar took his son's ashes to Fort Morgan, Colorado. When his twin sister, Jane, died, her tombstone had both their names carved on it, with an empty space for Dick's death date. Brother and sister were eventually buried next to each other.

Career

Dick sold his first story in 1952. From that point on he wrote full-time, selling his first novel in 1955. The 1950s were a difficult and impoverished time for Dick. He once said, "We couldn't even pay the late fees on a library book." He published almost exclusively within the science fiction genre, but dreamed of a career in the mainstream of American literature. During the 1950s he produced a series of nongenre, non-science fiction novels. In 1960 he wrote that he was willing to "take twenty to thirty years to succeed as a literary writer." The dream of mainstream success formally died in January 1963 when the Scott Meredith Literary Agency returned all of his unsold mainstream novels. Only one of these works, Confessions of a Crap Artist, was published during Dick’s lifetime.[3]

In 1963, Dick won the Hugo Award for The Man in the High Castle. Although he was hailed as a genius in the science fiction world, the mainstream literary world was unappreciative, and he could publish books only through low-paying science fiction publishers such as Ace. Even in his later years, he continued to have financial troubles. In the introduction to the 1980 short story collection The Golden Man, Dick wrote:

Several years ago, when I was ill, Heinlein offered his help, anything he could do, and we had never met; he would phone me to cheer me up and see how I was doing. He wanted to buy me an electric typewriter, God bless him—one of the few true gentlemen in this world. I don't agree with any ideas he puts forth in his writing, but that is neither here nor there. One time when I owed the IRS a lot of money and couldn't raise it, Heinlein loaned the money to me. I think a great deal of him and his wife; I dedicated a book to them in appreciation. Robert Heinlein is a fine-looking man, very impressive and very military in stance; you can tell he has a military background, even to the haircut. He knows I'm a flipped-out freak and still he helped me and my wife when we were in trouble. That is the best in humanity, there; that is who and what I love.[4]

The last novel published during Dick's life was The Transmigration of Timothy Archer. In 1972, Dick donated his manuscripts and papers to the Special Collections Library at California State University, Fullerton where they are archived in the Philip K. Dick Science Fiction Collection in the Pollak Library. It was in Fullerton that Philip K. Dick befriended budding science-fiction writers K. W. Jeter, James Blaylock, and Tim Powers.

Style and works

Pen names

Dick occasionally wrote under pen names, most notably Richard Philips and Jack Dowland. The surname Dowland refers to composer John Dowland, who is featured in several works. The title Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said directly refers to Dowland's best-known composition, Flow My Tears.

The short story "Orpheus with Clay Feet" was published under the pen name "Jack Dowland." The protagonist desires to be the muse for fictional author Jack Dowland, considered the greatest science fiction author of the twentieth century. In the story, Dowland publishes a short story titled "Orpheus with Clay Feet," under the pen name "Philip K. Dick." In the semi-autobiographical novel VALIS, the protagonist is named "Horselover Fat"; "Philip," or "Phil-Hippos," is Greek for "horselover," while "dick" is German for "fat" (a cognate of thick).

Although he never used it himself, Dick's fans and critics often refer to him familiarly as "PKD" (cf. Jorge Luis Borges' "JLB"), and use the comparative literary adjectives "Dickian" and "Phildickian" in describing his style and themes (cf. Kafkaesque, Orwellian).

Themes

Dick's stories typically focus on the fragile nature of what is "real" and the construction of personal identity. His stories often become "surreal" fantasies as the main characters slowly discover that their everyday world is actually an illusion constructed by powerful external entities (such as in Ubik), vast political conspiracies, or simply from the vicissitudes of an unreliable narrator. "All of his work starts with the basic assumption that there cannot be one, single, objective reality," writes science fiction author Charles Platt. "Everything is a matter of perception. The ground is liable to shift under your feet. A protagonist may find himself living out another person's dream, or he may enter a drug-induced state that actually makes better sense than the real world, or he may cross into a different universe completely."[2]

Alternate universes and simulacra were common plot devices, with fictional worlds inhabited by common, working people, rather than galactic elites: "I want to write about people I love, and put them into a fictional world spun out of my own mind, not the world we actually have, because the world we actually have does not meet my standards."[5]

"There are no heroes in Dick's books," Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, "but there are heroics. One is reminded of Dickens: what counts is the honesty, constancy, kindness and patience of ordinary people."[6] Dick made no secret that much of his ideas and work were heavily influenced by the writings of Carl Jung, the Swiss founder of the theory of the human psyche he called Analytical Psychology (to distinguish it from Freud's theory of psychoanalysis). Jung was a self-taught expert on the unconscious and mythological foundations of conscious experience and was open to the reality underlying mystical experiences. The Jungian constructs and models that most concerned Dick seem to be the archetypes of the collective unconscious, group projection/ hallucination, synchronicities, and personality theory. Many of Dick's protagonists overtly analyze reality and their perceptions in Jungian terms (see Lies Inc.). Dick's self-named "Exegesis" also contained many notes on Jung in relation to theology and mysticism.

Mental illness was a constant interest of Dick's, and themes of mental illness permeate his work. The character Jack Bohlen in the 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip is an "ex-schizophrenic." The novel Clans of the Alphane Moon centers on an entire society made up of descendants of lunatic asylum inmates. In 1965 he wrote the essay titled Schizophrenia and the Book of Changes.[1]

Drug use was also a theme in many of Dick’s works, such as A Scanner Darkly and The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. Dick wrote all of his books published before 1970 high on amphetamines. "A Scanner Darkly (1977) was the first complete novel I had written without speed," said Dick in a 1975 interview. He also experimented briefly with psychedelics, but wrote The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, which Rolling Stone dubs "the classic LSD novel of all time," before he had ever tried them.[7]

Selected works

The Man in the High Castle (1962) occurs in an alternate universe United States ruled by the victorious Axis powers. It is the only Dick novel to win a Hugo Award. In 2015 it was adapted into a television series by Amazon Studios.

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965) utilizes an array of science fiction concepts and features several layers of reality and unreality. It is also one of Dick’s first works to explore religious themes. The novel takes place in the twenty-first century, when, under United Nations authority, mankind has colonized the solar system's every habitable planet and moon. Life is physically daunting and psychologically monotonous for most colonists, so the UN must draft people to go to the colonies. Most entertain themselves using "Perky Pat" dolls and accessories manufactured by Earth-based "P.P. Layouts." The company also secretly creates "Can-D," an illegal but widely available hallucinogenic drug allowing the user to "translate" into Perky Pat (if the drug user is a woman) or Pat's boyfriend, Walt (if the drug user is a man). This recreational use of Can-D allows colonists to experience a few minutes of an idealized life on Earth by participating in a collective hallucination.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) is the story of a bounty hunter policing the local android population. It occurs on a dying, poisoned Earth de-populated of all "successful" humans; the only remaining inhabitants of the planet are people with no prospects off-world. Androids, also known as "andys," all have a preset "death" date. However, a few "andys" seek to escape this fate and supplant the humans on Earth. The 1968 story is the literary source of the film Blade Runner (1982). It is both a conflation and an intensification of the pivotally Dickian questioning of the nature of reality. Are the human-looking and human-acting androids fake or real humans? Should we treat them as machines or as people? What crucial factor defines humanity as distinctly 'alive', versus those merely alive only in their outward appearance?

Ubik (1969) uses extensive networks of psychics and a suspended state after death in creating a state of eroding reality. A group of psychics is sent to investigate a group of rival psychics, but several of them are apparently killed by a saboteur's bomb. Much of the novel fluctuates between a number of equally plausible realities; the "real" reality, a state of half-life and psychically manipulated realities. Time Magazine listed it among the "All-TIME 100 Greatest Novels" published since 1923.[8]

Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (1974) concerns Jason Taverner, a television star living in a dystopian near-future police state. After he is attacked by an angry ex-girlfriend, Taverner awakens in a dingy Los Angeles hotel room. He still has his money in his wallet, but his identification cards are missing. This is no minor inconvenience, as security checkpoints (manned by "pols" and "nats," the police and National Guard) are set up throughout the city to stop and arrest anyone without valid ID. Jason at first thinks that he was robbed, but soon discovers that his entire identity has been erased. There is no record of him in any official database, and even his closest associates do not recognize or remember him. For the first time in many years, Jason cannot rely on his fame or reputation. He has only his innate charisma to help him as he tries to find out what happened to his past and avoid the attention of the "pols." The novel was Dick's first published novel after years of silence, during which time his critical reputation had grown, and this novel was awarded the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. It is the only Philip K. Dick novel nominated both for a Hugo and for a Nebula Award.

In an essay written two years before dying, Dick described how he learned from his Episcopalian priest that an important scene in Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said–involving its other main character, Police General Felix Buckman, the policeman of the title–was very similar to a scene in the Book of Acts. Film director Richard Linklater discusses this novel in his film Waking Life, which begins with a scene reminiscent of another Dick novel, Time Out of Joint.

A Scanner Darkly (1977) is a bleak mixture of science fiction and police procedural novels; in its story, an undercover narcotics police detective begins to lose touch with reality after falling victim to the same permanently mind altering drug, Substance D, he was enlisted to help fight. Substance D is instantly addictive, beginning with a pleasant euphoria which is quickly replaced with increasing confusion, hallucinations and eventually total psychosis. In this novel, as with all Dick novels, there is an underlying thread of paranoia and dissociation with multiple realities perceived simultaneously. It was adapted to film by Richard Linklater.

VALIS, (1980) is perhaps Dick’s most postmodern and autobiographical novel, examining his own unexplained experiences (see above). It may also be his most academically studied work, and was adapted as an opera by Tod Machover. Later works like the VALIS trilogy were heavily autobiographical, many with "two-three-seventy-four" (2-3-74) references and influences. The word VALIS is the acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System; it is the title of a novel (and is continued thematically in at least three more novels). Later, PKD theorized that VALIS was both a "reality generator" and a means of extraterrestrial communication. A fourth VALIS manuscript, Radio Free Albemuth, although composed in 1976, was discovered after his death and published in 1985.

In addition to 36 novels, Dick wrote approximately 121 short stories, many of which appeared in science fiction magazines.

Despite his feeling that he was somehow experiencing a divine communication, Dick was never fully able to rationalize the events. For the rest of his life, he struggled to comprehend what was occurring, questioning his own sanity and perception of reality. He transcribed what thoughts he could into an 8,000-page, 1-million-word journal dubbed the Exegesis. From 1974 until his death in 1982, Dick spent sleepless nights writing in this journal, often under the influence of prescription amphetamines. A recurring theme in Exegesis is PKD's hypothesis that history had been stopped in the first century C.E., and that "the Empire never ended." He saw Rome as the pinnacle of materialism and despotism, which, after forcing the Gnostics underground, had kept the population of Earth enslaved to worldly possessions. Dick believed that VALIS had communicated with him, and anonymous others, to induce the impeachment of U.S. President Richard M. Nixon, whom Dick believed to be the current Emperor of Rome incarnate.

Influence and legacy

Lawrence Sutin's biography of Dick, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick, is considered the standard biographical treatment of Dick's life.[1]

In 2004, French writer Emmanuel Carrère published I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey Into the Mind of Philip K. Dick, which the author describes in his preface in this way:

The book you hold in your hands is a very peculiar book. I have tried to depict the life of Philip K. Dick from the inside, in other words, with the same freedom and empathy – indeed with the same truth – with which he depicted his own characters.[9]

Critics of the book have complained about the lack of fact checking, sourcing, notes, and index, all of which would be usual in an authoritative biography. It can be considered a nonfiction novel about his life.

Although Dick struggled to achieve mainstream recognition during his lifetime, several of his stories have been adapted into popular films since his death. In 2005, Time Magazine named Ubik one of the one hundred greatest English-language novels published since 1923.[8] In 2007, Dick became the first science fiction writer to be included in The Library of America series.[10][11]

Dick influenced many writers, including William Gibson, Jonathan Lethem, and Ursula K. Le Guin. Dick has also influenced numerous filmmakers, his work being compared to films such as the Wachowski brothers's The Matrix, David Cronenberg's Videodrome, Charlie Kaufman's Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,[12] among others.

Dick was "resurrected" by his fans in the form of a simulacrum or remote-controlled android designed in his likeness. The android of Philip K. Dick was impaneled in a San Diego Comic Con presentation about the film adaptation of the novel, A Scanner Darkly. In February 2006, an America West Airlines employee misplaced the android, and it has not yet been found.[13] In January 2011, it was announced that Hanson Robotics had built a replacement.[14]

Adaptations

Films

A number of Dick's stories have been made into films. Dick himself wrote a screenplay for an intended film adaptation of Ubik in 1974, but the film was never made. Many film adaptations have not used Dick's original titles. When asked why this was, Dick's ex-wife Tessa said, "Actually, the books rarely carry Phil's original titles, as the editors usually wrote new titles after reading his manuscripts. Phil often commented that he couldn't write good titles. If he could, he would have been an advertising writer instead of a novelist."[15]

The most famous film adaptation is Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (based on Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). A screenplay had been in the works for years before Scott took the helm, but Dick was extremely critical of all versions. Dick was still apprehensive about how his story would be adapted for the film when the project was finally put into motion. Among other things, he refused to do a novelization of the film. But contrary to his initial reactions, when he was given an opportunity to see some of the special effects sequences of Los Angeles 2019, Dick was amazed that the environment was "exactly as how I'd imagined it!" Following the screening, Dick and Scott had a frank but cordial discussion of Blade Runner's themes and characters, and although they had incredibly differing views, Dick fully backed the film from then on. Dick died from a stroke less than four months before the release of the film.

Total Recall (1990), based on the short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale," evokes a feeling similar to that of the original story while streamlining the plot; however, the action-film protagonist is totally unlike Dick's typical nebbishy protagonist, a fearful and insecure anti-hero. The film includes such Dickian elements as the confusion of fantasy and reality, the progression towards more fantastic elements as the story progresses, machines talking back to humans, and the protagonist's doubts about his own identity. Total Recall 2070 (1999), a single season Canadian TV show (22 episodes), based on thematic elements from "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and interwoven with snippets of other Dick stories, is much closer in feel to both Dick's works than the better-known films based on them. The main character is aptly named David Hume.

Steven Spielberg's adaptation of "The Minority Report" faithfully translates many of Dick's themes, but changes major plot points and adds an action-adventure framework.

Dick's 1953 story "Impostor" has been adapted twice: first in 1962 for the British anthology television series Out of This World and then in 2002 for the movie Impostor. Impostor utilizes two of Dick's most common themes: mental illness, which diminishes the sufferer's ability to discriminate between reality and hallucination, and a protagonist persecuted by an oppressive government.

The film Screamers (1995) was based on a Dick short story "Second Variety"; the location was altered from a war-devastated Earth to a generic science fiction environment of a distant planet. A sequel, titled Screamers 2, is currently in production.

John Woo's 2003 film, Paycheck, was a very loose adaptation of Dick's short story of that name, and suffered greatly both at the hands of critics and at the box office.

The French film Confessions d'un Barjo (Barjo in English-language release) is based on Dick's non-science-fiction book Confessions of a Crap Artist. Reflecting Dick's popularity and critical respect in France, Barjo faithfully conveys a strong sense of Dick's aesthetic sensibility, unseen in the better-known film adaptations. A brief science fiction homage is slipped into the film in the form of a TV show.

The live action/animated film, A Scanner Darkly (2006) was directed by Richard Linklater and stars Keanu Reeves as Fred/Bob Arctor and Winona Ryder as Donna. Robert Downey Jr. and Woody Harrelson, actors both noted for drug issues, were also cast in the film. The film was produced using the process of rotoscoping: it was first shot in live-action and then the live footage was animated over.

Next (2007), directed by Lee Tamahori and starring Nicolas Cage, was loosely based on the short story "The Golden Man."

Radio Free Albemuth (2010), directed by John Alan Simon, was loosely based on the novel Radio Free Albemuth.

The Adjustment Bureau (2011), directed by George Nolfi and starring Matt Damon, was loosely based on the short story "Adjustment Team".

Total Recall (2012), directed by Len Wiseman and starring Colin Farrell, is a second film adaptation of the short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale."

Blade Runner 2049 (2017), directed by Denis Villeneuve and starring Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford, is a sequel to the 1982 film Blade Runner, based on Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Television

It was reported in 2010 that Ridley Scott would produce an adaptation of The Man in the High Castle in the form of a mini-series. It was created by Frank Spotnitz and is produced by Amazon Studios, Ridley Scott's Scott Free Productions (with Scott serving as executive producer), Headline Pictures, Electric Shepherd Productions, and Big Light Productions. The pilot premiered in January 2015, and Amazon ordered a ten-episode season the following month which was released in November. A second season of ten episodes premiered in December 2016, and a third season was released on October 5, 2018. The fourth and final season premiered on November 15, 2019.

In late 2015, Fox aired Minority Report, a television series sequel adaptation to the 2002 film of the same name based on Dick's short story "The Minority Report" (1956). The show was cancelled after one season.

Philip K. Dick's Electric Dreams, or simply Electric Dreams, is a science fiction television anthology series, produced by Sony Pictures Television with Ronald D. Moore, Michael Dinner, and Bryan Cranston serving as executive producers. The series consists of ten standalone 50-minute episodes based on Dick's work. It premiered on Channel 4 in the United Kingdom on September 17, 2017, and in the United States on Amazon Prime Video on January 12, 2018.

Stage and Radio

At least two of Dick's works have been adapted for the stage. The first was the opera VALIS, composed and with libretto by Tod Machover, which premiered at the Pompidou Center in Paris on December 1, 1987, with a French libretto. It was subsequently revised and readapted into English, and was recorded and released on CD (Bridge Records BCD9007) in 1988. The second known stage adaptation was Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said, produced by the New York-based avant-garde company Mabou Mines. It premiered in Boston at the Boston Shakespeare Theatre (June 18-30, 1985) and was subsequently staged in New York and Chicago.

A radio drama adaptation of Dick's short story "Mr. Spaceship" was aired by the Finnish Broadcasting Company (Yleisradio) in 1996 under the name Menolippu Paratiisiin. Radio dramatizations of Dick's short stories Colony and The Defenders were aired by NBC in radio as part of the series X Minus One.

Contemporary philosophy

Few other writers of fiction have had such an impact on contemporary philosophy as Dick. His foreshadowing of postmodernity has been noted by philosophers as diverse as Jean Baudrillard, Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek. Žižek is especially fond of using Dick's short stories to articulate the ideas of Jacques Lacan.[16]

Jean Baudrillard offers this interpretation:

It is hyperreal. It is a universe of simulation, which is something altogether different. And this is so not because Dick speaks specifically of simulacra. SF has always done so, but it has always played upon the double, on artificial replication or imaginary duplication, whereas here the double has disappeared. There is no more double; one is always already in the other world, an other world which is not another, without mirrors or projection or utopias as means for reflection. The simulation is impassable, unsurpassable, checkmated, without exteriority. We can no longer move "through the mirror" to the other side, as we could during the golden age of transcendence.[17]

Awards and honors

During his lifetime, Dick received the following awards and nominations:

- Hugo Awards

- Best Novel

- 1963 - winner: The Man in the High Castle

- 1975 - nominee: Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said

- Best Novelette

- 1968 - nominee: Faith of Our Fathers

- Best Novel

- Nebula Awards

- Best Novel

- 1965 - nominee: Dr. Bloodmoney

- 1965 - nominee: The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

- 1968 - nominee: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

- 1974 - nominee: Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said

- 1982 - nominee: The Transmigration of Timothy Archer

- Best Novel

- John W. Campbell Memorial Award

- Best Novel

- 1975 - winner: Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said

- Best Novel

- Graouilly d'Or (Festival de Metz, France)

- 1979 - winner: A Scanner Darkly

Also of note is the convention Norwescon which each year presents the Philip K. Dick Award, a science fiction award]] that annually recognizes the previous year's best SF paperback original published in the U.S.[18] The award was inaugurated in 1983, the year after Dick's death.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lawrence Sutin, Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick (Carroll & Graf, 2005, ISBN 0786716231).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Charles Platt, Dream Makers: The Uncommon People Who Write Science Fiction (Berkley Publishing, 1980, ISBN 0425046680).

- ↑ Philip K. Dick, Philip K. Dick: The Last Interview: and Other Conversations (Melville House, 2015, ISBN 978-1612195261).

- ↑ Philip K. Dick, The Golden Man (Berkley Books, 1980, ISBN 042504288X).

- ↑ Science Fiction quotes #3 IJAD Dance Company, October 28, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Philip K(indred) Dick 1928 - 1982 DISCovering Authors, Gale Research Inc., 1996. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ↑ Paul Williams, The Most Brilliant Sci-Fi Mind on Any Planet: Philip K. Dick Rolling Stone, November 6, 1975. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo, All-TIME 100 Novels TIME Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Emmanuel Carrère, I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey Into the Mind of Philp K. Dick (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004, ISBN 0805054642).

- ↑ Judy Stoffman, A milestone in literary heritage Toronto Star, February 10, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Library of America to issue volume of Philip K. Dick USA Today, November 28, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Peter Bradshaw, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, The Guardian, April 30, 2004. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ↑ Sharon Waxman, A Strange Loss of Face, More Than Embarrassing The New York Times, June 24, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Cyriaque Lamar, The Lost Robotic Head of Philip K Dick Has Been Rebuilt io9, January 12, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Annie Knight, About Philip K. Dick: An interview with Tessa, Chris, and Ranea Dick Far Sector SFFH, November 2002. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek, The Desert and the Real Lacan.com. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Science Fiction Science Fiction Studies 18(3) (November 1991). Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ Philip K. Dick Award Retrieved August 7, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carrère, Emmanuel. I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey Into the Mind of Philp K. Dick. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004. ISBN 0805054642

- Dick, Philip K. The Golden Man. Berkley Books, 1980 ISBN 042504288X

- Dick, Philip K. Philip K. Dick: The Last Interview: and Other Conversations. Melville House, 2015. ISBN 978-1612195261

- Platt, Charles. Dream Makers: The Uncommon People Who Write Science Fiction. Berkley Publishing, 1980. ISBN 0425046680

- Sutin, Lawrence. Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. Carroll & Graf, 2005. ISBN 0786716231

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

- The Philip K. Dick Bookshelf

- Blows Against the Empire – The New Yorker's Adam Gopnik on Philip K. Dick

- VALBS - An online secondary bibliography on Dick and his works

- The Second Coming of Philip K. Dick – by Frank Rose, an article from Wired about movies based on the Dick's novels

- Philip K. Dick: A Visionary Among the Charlatans – Stanislaw Lem's essay about the state of American science fiction circa 1975 with an extended appreciation of Dick

- Philip K. Dick at the Internet Movie Database

- Philip K. Dick at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Philip K. Dick Dark Roasted Blend

- The Last Days of Philip K. Dick

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.