Katharine Meyer Graham (June 16, 1917 â July 17, 2001) was an American publisher. She led her family's newspaper, The Washington Post, for more than two decades, overseeing its most famous period, the Watergate scandal coverage that eventually led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. She has been widely described as one of the most powerful American women of the twentieth century.

Life

Katharine Meyer Graham was born on June 16, 1917, in New York City to a family of French and German heritage. With a Jewish father and Lutheran mother, her ancestors counted amongst their ranks many important religious leaders, both rabbis and ministers. Katharine's father, Eugene Meyer, was a financier and later a public official, who made his fortune playing the Wall Street stockmarket. He bought The Washington Post as an insecure and unproved investment in 1933 at a bankruptcy auction. Katharine's mother, Agnes Ernst, was a bohemian intellectual, art lover, and political activist almost at odds with the members of her cherished Republican party. She shared friendships with French intellectuals and scientistsâpeople as diverse as Auguste Rodin, Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Agnes Meyer also worked as a newspaper reporter at a time when journalism was an quite an uncommon profession among women, perhaps inspiring her young daughter Katharine to eventually do the same.

The Meyers' opulent wealth allowed Katharine and her four siblings to live a privileged, sheltered childhood, filled with all the best things that money could buy. Her parents owned several homes across the country, primarily living back and forth between a veritable "castle" in Mount Kisco, New York and a smaller home in Washington, D.C. However, she often felt abandoned by her parents, who traveled and socialized extensively during her childhood, leaving Katharine and her siblings to be raised mostly by nannies, governesses, and tutors. The children actually stayed in Washington D.C. by themselves for many years while their parents lived almost full-time at the Mount Kisco estate. In Mrs. Meyers' private diaries Katharine is not mentioned until she was almost three years old, and even then only in passing.

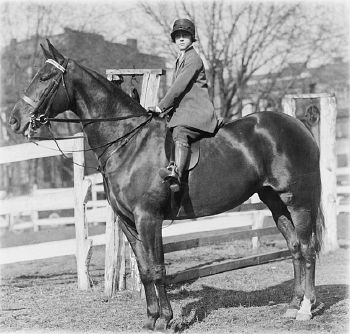

Still, Katharine attended the most elite of schools, enjoyed tennis instruction by Wimbledon champions, and was presented as a debutante. She never learned the simple domestic skills commonly taught to most girls of her time, such as sewing and cooking, and consequently, as a young adult, Katharine felt she had been sheltered and somewhat isolated by such privilege. However, her elder sister Florence Meyer (1911-1962) felt no such embarrassment and enjoyed their family's indulgence, becoming a successful photographer and Hollywood wife of actor Oscar Homolka.

Katharine (nicknamed "Kay") attended the exclusive Madeira School, an institution to which her father had also donated a generous amount of land. After graduating she went on to the then all-female Vassar College, eventually transferring to the University of Chicago to study journalism. While in Chicago, she defied her East coast blue-blooded upbringing to become quite interested in the labor issues of the city, sharing friendships with people from all walks of life, mostly very different from her own. She would later call upon this experience, as well as one she had while working at a San Francisco newspaper after graduation covering a major strike by wharf workers, to defeat a union revolt at what would become her own paper (The Washington Post) during the 1970s.

Katharine first began working for the Post as a reporter in 1938. In 1939, she advanced on to humorous editorial pieces, mostly breezy and lighthearted musings on the life of a young socialite. While in Washington D.C., Kay met an old Chicago friend and schoolmate, and fellow journalist Will Lang Jr. The two dated for a while, but broke off the relationship due to conflicting interests. Lang would later achieve notoriety for his coverage of the rebuilding of the Berlin wall and the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Kay continued working at the Post. Sharing a title of staff journalist there with her was the man who was to become her husband, Philip Graham. After a whirlwind romance, on June 5, 1940, they married. Philip Graham was a graduate of Harvard Law School and a clerk for Stanley Reed and later Felix Frankfurter, both of the U.S. Supreme Court. (Philip Graham's younger brother, Bob Graham, would go on to become Governor of Florida and a long-time U.S. Senator.) The couple decided that they would rather not live off her great wealth, but instead would both work and live from their own salaries however meager. He started working as a law clerk and she continued writing at the Post. The couple enjoyed an active social life hobnobbing with Washington's most prominent governmental and journalistic elite.

During World War II, Philip Graham enlisted in the Army Air Corps as a private, and rose to the rank of major. Katharine followed him on many military assignments including those to Sioux Falls, South Dakota and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. In 1945, Graham went to the Pacific theater as an intelligence officer of the Far East Air Force. He would later draw on his military intelligence training to become a coveted, trusted confidante of Lyndon B. Johnson, and John F. Kennedy. Conspiracy theorists later cited this close friendship, and consequential, possible privy knowledge of top governmental secrets, as evidence that perhaps his suicide could be considered suspicious, despite the fact that Graham himself admitted to suffering from manic-depression and alcoholism.

In addition to the burden of maintaining a relationship with a loving, though emotionally unstable husband, Katharine had to endure the stillbirth of their first child, and several subsequent miscarriages. Happily, though, the couple eventually had four healthy children: Elizabeth ("Lally") Morris Graham (later Weymouth), born on July 3, 1943, Donald Edward Graham, April 22, 1945, William Welsh Graham (1948), and Stephen Meyer Graham (1952). After the birth of Donald, Katharine left the Post to raise her family. (Lally Weymouth became a prominent conservative journalist, and Donald Graham the chairman of the Post.)

Philip Graham became publisher of the Washington Post in 1946, when Katharine's father Eugene Meyer left that position to become head of the World Bank. Their family complete, with Philip at work at the Post, and Kay at home with the kids, the Grahams enjoyed the perks of being a part of a prominent political and social circle. They were important members of the Washington social scene, becoming friends with John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Robert Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, and Henry Kissinger, among many others. In her 1997 autobiography, Graham commented several times about how close her husband was to politicians of his day, and how such personal closeness with politicians later became unacceptable in journalism.

In 2001, Graham suffered a fall while visiting Boise, Idaho. She died three days after the fall, on July 17, 2001, due to trauma resulting from her fall-related head injury. Her funeral took place at the Washington National Cathedral.

Work

Katharine Graham was connected to the Washington Post from an early age. Her father bought the newspaper; she joined its staff as a reporter; her husband became its publisher; and, finally, she inherited the leadership of this influential publication and its entire company.

Philip Graham's illness and death

Eugene Meyer, the Wall Street tycoon and Katharine's father, who had earlier saved the Washington Post from certain death, thought well of his son-in-law, Philip, and when he left his position at the Post to head the World Bank, passed on his leadership to him. Philip Graham thus became publisher and editor of the Post in 1946. Although Meyer left that position only six months later, he was to technically remain chairman of the Washington Post Company until his death in 1959, at which time Philip Graham would finally possess sole control of not only the Washington Post newspaper, but also now the entire company itself. He would soon expand its media empire through a risky purchase, television stationsâtelevision at the time still being a new sensationâand the old stalwart Newsweek magazine. Such risk taking was a hallmark of his emotionally instability, yet also largely responsible for the Washington Post's huge expansion during this time.

After several years of erratic behavior and sullen, depressed, and introverted times as well as magnanimous, hard-working, brilliant times, later diagnosed as bipolar disorder, Philip Graham suffered a nervous breakdown. Also around this time, Katharine discovered her husband had been cheating on her with Robin Webb, an Australian stringer for Newsweek. Her husband declared that he would divorce Katharine for Robin and he made motions to divide up the couple's assets.

At a newspaper conference in Phoenix, Arizona, Philip Graham, either drunk, having a nervous breakdown, or both, told the audience that President Kennedy was having an affair with Mary Pinchot Meyer. Katharine flew to Arizona to retrieve him by private jet, and her sedated husband was flown back to Washington. Philip was taken to the private Chestnut Lodge psychiatric facility near Washington, D.C. He was released after a short stay; subsequently suffered major depression; and then returned to the facility. In 1963, during a weekend release from Chestnut Lodge at the couple's Glen Welby home, he committed suicide.

Ascent to power

Katharine Graham, forced to saddle up due to tragic circumstances beyond her control, had no choice but to grab the reins of the company her father created, her husband helmed, and steer it, somehow, into the future. She had not worked or written anything of substance since the birth of her children. Riddled with doubt, insecure as always, she wondered what to do, what would really be best, for the Washington Post and the Washington Post company. It was widely assumed that her lack of management experience and entrepreneurial insight would leave her no choice but to sell or hand over control to a more experienced proxy. But she proved them wrong. At the age of 46, at a time when many working women were teachers, nurses, waitresses, or maids, Katharine Graham presided over what would become a Fortune 500 company.

Under her guidance, despite her extreme self doubt, the paper and the company grew in a way they never would have under anyone else. Unprepared, but resourceful, she made the pivotal decision to hire the roguish Ben Bradley as editor of the Post. During a press room strike of 1974, after union workers attempted to burn the press room down, she refused to give in to their demands. She stated coolly: "Why should I have my presses manned by 17 union workers when the job could be done by nine anybodies?" a move that did not endear her to socialists, but saved the paper millions of dollars. In fact the somewhat cut throat move allowed coveted previously union-only positions to be taken up by many minority workers.

Graham was the de facto publisher of the newspaper. She formally assumed the title in 1979, after becoming chairman of the board in 1973, holding the position until 1991. As the only woman to be in such a high position at a publishing company, she had no female role models and had difficulty being taken seriously by a many of her male colleagues and employees. She even sniffed warily, "Men are better at this job than women." Yet, it was her unsentimental attitude and directness of expression that many men actually found appealing and responded to openly. She preferred asking simple question rather than feigning expertise in an unstudied area. She insisted that she made endless mistakes, which she repeated rather tediously, yet resolved to learn from them in her own time. She was quoted as saying that women suffer more over their mistakes than men do. "We second guess ourselves. We're our own worst enemies...do you think that there's a man out there worrying about what he just wrote? Not one." Slowly but surely, not by protest but by example, she came to represent all that the burgeoning feminist movement was about. In an interview with National Public Radio in 1997, she modestly admitted that under her 30 years of guidance, profits of the Washington Post company grew from 100 million to slightly under two billion. She refused to take sole credit for it, insisting it was a group effort, a group that she "somehow" led.

Graham outlined in her memoir her lack of confidence and distrust in her own knowledge. The convergence of the women's movement with Graham's ascension to power at the Post brought about changes in Graham's attitude, and also led her to promote gender equality within her company. Under her leadership, the Post became known for its aggressive style of investigative reporting, increasing its circulation to become the most influential paper in Washington D.C. with significant impact throughout the nation. Graham had hired the brilliant Ben Bradlee as editor and had cultivated Warren Buffett for his financial advice. She had handled the unions; she had held her own with the "boys," but her most celebrated move involved the Watergate scandal.

Watergate

Graham presided over the Post at a crucial time in its history. The Post played an integral role in unveiling the Watergate conspiracy, which ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. The Nixon administration threatened to serve injunctions, have the paper shut down and arrest reporters. The Washington Post actually had to appeal their case to the U.S. Supreme Court to be granted permission to publish the Pentagon Papers, and break the scandal. Katharine defied her own lawyer's advice, who questioned taking on the very heartbeat of the American government, the White House itself. Even she admitted it was a potentially suicidal move.

Katharine Graham and editor Ben Bradlee experienced scores of challenges when they published the content of the Pentagon Papers, but they held fast, secure in the knowledge that the truth would speak for itself. When Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein initially brought the Watergate story to Bradlee, it was Graham who most ardently supported their investigative reporting, as well as supporting Bradlee in running the stories about Watergate when, perhaps frightened and under political pressure, most other news outlets were barely reporting on the matter.

In a humorous footnote to the Watergate scandal, Graham was the subject of one of the best-known threats in American journalistic history. This occurred in 1972, when Nixon's attorney general, John Mitchell, warned reporter Carl Bernstein "Katie Graham's gonna get caught in a big fat wringer if that's published."

Legacy

Katharine Graham had strong links to the Rockefeller family, serving both as a member of the Rockefeller University council and as a close friend of the Museum of Modern Art, where she was honored as a recipient of the David Rockefeller Award for enlightened generosity and advocacy of cultural and civic endeavors. She was a philanthropist who prided herself on backing the Send-A-Kid-To-Camp program, a charity which sent under-privileged children of the inner city of the district of Columbia to summer camp, providing them with what was for some their first taste of summer fun in the countryside with the freedom to experience nature and fresh air. She helped raise millions for this charity, and served on the board of the D.C. Child and Family Services.

The woman who described herself as "socially awkward," "painfully shy," and "just a doormat housewife" would eventually win America's highest journalistic honor. In 1997, Graham published her memoirs, Personal History. The book was praised for its honest portrayal of Philip Graham's mental illness, and received positive reviews for its depiction of her life as well as a glimpse into how the roles of women have changed during her lifetime. The book won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998.

The woman who once knew nothing of business management or corporate organization eventually headed a giant media conglomerate. A child whose own parents were not affectionate towards her and left her mostly to be raised by nannies, had a warm, close relationship with all four of her children, and left the family business in the care of her son Donald, when she stepped down. Katharine Graham, through steel will, self determination, jumping in feet first, and taking things one day at a time, created an institution and an ethos of uncompromising trust and integrity, and is remembered as a true Grande Dame. Her legacy is a newspaper, a corporation, a family, and an imprint on our history and our daily lives.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bradlee, Ben. 1995. A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684808943

- Gerber, Robin. 2005. Katharine Graham: The Leadership Journey of an American Icon. Portfolio Hardcover. ISBN 1591841046

- Graham, Katharine. 1997. Personal History. New York, NY: Knopf. ISBN 0394585852

- Graham, Katharine. 2002. Personal History (Women in History). Weidenfeld and Nicholson History. ISBN 1842126202

- Graham, Katharine. 2003. Katharine Graham's Washington. Vintage. ISBN 1400030595

External links

All links retrieved March 2, 2025.

- Katharine Graham: Newspaper Publisher, Watergate Figure Jone Johnson Lewis, ThoughtCo.

- Paid Notice: Deaths - Graham, Katherine New York Times, July, 18, 2001. Inserted by Rockefeller University and the Museum of Modern Art.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.