Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, Helsinki Accords, or Helsinki Declaration, was the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe held in Helsinki, Finland, between July 30 and August 1, 1975. Thirty-five European countries participated in addition to the United States and Canada. The aim was to reduce tension between East and West. The document was seen both as a significant step toward reducing Cold War tensions and as a major diplomatic boost for the Soviet Union at the time, due to its clauses on the inviolability of national borders and respect for territorial integrity, which were seen to consolidate the USSR's territorial gains in Eastern Europe following the Second World War.

On the other hand, by signing the document, the Soviet Union had also committed itself to transparency, to upholding civil and human rights and to non-violent resolution of disputes. Analysts identify a cause and effect relationship between the Accords and the eventual collapse of the Soviet bloc. While most if not all of the commitments were contained in the Charter of the United Nations and in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, several rights, such as the those of travel and of free speech, were given fresh prominence as a result of the Accords. Critics of the conference and of the Accords argued that détente should focus on arms control, that human rights and related matters detracted from the main agenda. However, the success of the Accords represent a triumph for non-aggressive diplomacy. As a result of the Accords, security slowly became understood by the post-Cold War era as indivisible and comprehensive—that one country cannot provide for its security at the expense of others. Some scholars suggest a Helsinki model for peace in Northeast Asia including the Korean peninsula.

Background

The Soviet Union had wanted a conference on security in Europe since the 1950s, eager to gain ratification of post-World War II boundaries and of its own role in Eastern Europe.[1] The Conference took three years to plan as delegates drafted the document.[2] It took place under provisions of the United Nations Charter (Chap. VIII). In 1976, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe was formalized to assist in monitoring the Accords and to sponsor future conferences, which took place in Belgrade (1977–78), Madrid (1980–83), and Ottawa (1985) and Paris (1990). Much of the negotiation surrounding the Accords was between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Richard Nixon's Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, led the U.S. team. At the time, Leonid Brezhnev was the Soviet Leader. It was, though, Gerald Ford, who signed the Accords for the U.S., having succeeded Nixon as President. Kissinger was not enthusiastic about the Accords; he is quoted as calling them "a bunch of crappy ideas."[3] Critics thought that détente should focus exclusively on arms control, not deal with civil issues. However, what the Accords set out to achieve was produce less than guidelines on "civilized conduct in Europe."[4] Provisions were discussed under three broad headings, described as "baskets," namely political, economic, and cultural which included education and human rights. The Soviet delegation tried to limit "basket three" while bolstering baskets one and two.[5] In contrast, a British diplomat stated, "if we don't lay eggs in the third basket, there will be none in the other ones either."[6] The Soviets wanted recognition of the status quo in Europe. When the conference met, it was the "largest assembly of European heads of state or government since the Congress of Vienna in 1815."[2]

Effectively, this amounted to a formal end to World War II because the Accords did in fact recognize the division of Germany and the "sensitive borders between Poland and East Germany and between Poland and the Soviet Union" as well as other boundaries in the region." Many of these borders had not been officially recognized since the end of the war. All this was in exchange for "a Soviet promise to increase trade, cultural contacts, and the protection of human rights across all Europe."[7] The Soviets also recognized the status of Berlin "occupied since 1945 by the French, British and U.S. armies" and, radically, agreed to relax travel restrictions between the two German states.[8] Arguably, the object of reducing tension between the two rival blocs was achieved. The Soviet Union walked away with almost everything it had wanted and so did the West. The Accords have been described by both sides as the "high point of détente."[9] At the conference, Ford was sat between Brezhnev and the East German leader, Erich Honecker.[10]

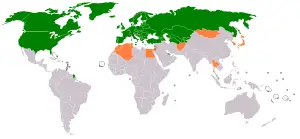

Signatory countries

United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, the German Democratic Republic, the Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, the Holy See, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Yugoslavia; excluding Albania and Andorra).

The guiding principles of the Act

The Act's "Declaration on Principles Guiding Relations between Participating States" (also known as "The Decalogue")

- Enumerated the following 10 points:

- I. Sovereign equality, respect for the rights inherent in sovereignty

- II. Refraining from the threat or use of force

- III. Inviolability of frontiers

- IV. Territorial integrity of States

- V. Peaceful settlement of disputes

- VI. Non-intervention in internal affairs

- VII. Respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of thought, conscience, religion or belief

- VIII. Equal rights and self-determination of peoples

- IX. Co-operation among States

- X. Fulfillment in good faith of obligations under international law

Consequences

The civil rights portion of the agreement provided the basis for the work of the Moscow Helsinki Group, an independent non-governmental organization created to monitor compliance to the Helsinki Accords (which evolved into several regional committees, eventually forming the International Helsinki Federation and Human Rights Watch). No more legally binding than previous Declarations, the Accords did give new impetus to protecting human rights. Also, signatories did agree to additional conferences to monitor compliance.[11] While these provisions applied to all signatories, the focus of attention was on their application to the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies, including Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. Although some leaders of the Moscow Monitoring Group were imprisoned for their activities, the Group became "a leading dissident center" and analysts say that the Helsinki Accords provided a new framework and context for the expression of dissident voices.[12] Dizard says that while compliance with the provisions of the Accords was "slow from the Soviet side" they "played a special role in preparing the way for the eventual collapse of communist rule in East Europe and the Soviet Union."[12] Brinkley agrees that it was the Accords' "call for openness and respect for human rights" that marked "the beginning of the end of the Soviet domination of East Europe."[2] The Accords also obligated the Soviet Union to share some information on military movements with the West.

A cause and effect link has been argued for the rise of Solidarity in Poland and of other, similar movements across the former Soviet bloc. [13] According to the Cold War scholar John Lewis Gaddis in his book The Cold War: A New History (2005), "Brezhnev had looked forward, Anatoly Dobrynin recalls, to the 'publicity he would gain… when the Soviet public learned of the final settlement of the postwar boundaries for which they had sacrificed so much'… '[Instead, the Helsinki Accords] gradually became a manifesto of the dissident and liberal movement'… What this meant was that the people who lived under these systems—at least the more courageous—could claim official permission to say what they thought."[14] Recognition of the right of travel led to 500,000 Soviet Jews migrating to Israel, says Drinan.[13]

Mount regards the fall of the Berlin Wall as a consequence of the accords, since it allowed journalists from the West to enter East Germany whose reports could then be heard in the East on West German television and radio.[15] Basket Three included commitments to open up the air waves, that is, by ceasing jamming transmissions from the West. Dizard says that the steady "cutback on jamming" following the Accords gave millions in the East access to Western broadcasts.[16] When the OSCE met in 1990, it recognized Germany's reunification. President Ford was criticized at the time for signing the Accords, which some considered contained too many concessions. Later, he regarded this as one of the most notable achievements of his Presidency and included a piece of the Berlin Wall in his Presidential Library at Grand Rapids, Michigan.[17] Mount also acknowledges the role played by the West German Chancellor, Willy Brandt, whose policy of Ostpolik or openness to the East led to a resolution of the border issue and paved the way for Helsinki. Without Brandt, says Mount, the Accords would have been impossible.[18]

Legacy

In addition to creating a climate for the development of dissident movements in the Communist world, which called for greater freedom, democracy and an end to totalitarian oppression, the Accords attest that diplomacy and negotiation can change the world. As Ford said, the Accords saw some of the most closed and oppressive regimes make a public commitment to allow their citizens "greater freedom and movement" which served as a "yardstick" by which the world could measure "how well they live up to the stated intentions."[19] Ford and others at Helsinki were convinced that normalization of relations with the Soviet Union would not restrict matters of discussion only to those of defense but include cultural exchange and commerce, which could lead to a lessening of tension. "Surely" said Ford "this is in the best interest of the United States and of the peace of the world."[19] Cultural and commercial encounters made possible by the Accords helped each side to see the other as fellow humans, with artistic and other interests in common. The stereotypes of the other as the "enemy" became harder to sustain. One eminent Soviet scholar described the Accords as marking the start of a "new phase of international relations, which finds its expression in the strengthening of international ties and cooperation in the fields of economy, science, and culture."[20] Yale argues that more than anything else, it was cultural exchange that ended communism in the Soviet Union. Over a period of 35 years, such exchange took place "under agreements" such as the Helsinki Accords "concluded with the Soviet government" and "at a cost minuscule in comparison with U.S. expenditure on defense and intelligence."[21]

Notes

- ↑ Brinkley (2007), 111.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Brinkley (2007), 106.

- ↑ Brinkley, 110.

- ↑ Brinkley, 107.

- ↑ Drinan (2001), 105.

- ↑ Dizard (2001), 105.

- ↑ Thompson (2004), 268.

- ↑ Mount and Gauthier (2006), 127.

- ↑ Bagby (1999), 295.

- ↑ Brinkley (2007), 111.

- ↑ Dizard (2001), 105.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dizard (2001), 90.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Drinan (2001), 73.

- ↑ Gaddis (2005), 190.

- ↑ Mount and Gauthier (2006), 127-128.

- ↑ Dizard (2001), 106.

- ↑ Mount and Gauthier (2006), xxii.

- ↑ Mount and Gauthier (2006), 110.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Brinkley (2007), 110.

- ↑ Richmond (2004), 43. citing Aleksei R. Khokhlov.

- ↑ Richmond (2004), xiii-xiv.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bagby, Wesley Marvin. 1999. America's International Relations Since World War I. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780813341453.

- Brinkley, Douglas. 2007. Gerald R. Ford. New York, NY: Times Books. ISBN 9780805069099.

- Dizard, Wilson P. 2001. Digital Diplomacy: U.S. Foreign Policy in the Information Age. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780275972271.

- Drinan, Robert F. 2001. The Mobilization of Shame: A World View of Human Rights. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088250.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. 2005. The Cold War: A New History. New York, NY: Penguin Press. ISBN 9781594200625.

- Mount, Graeme S., and Mark Gauthier. 2006. 895 Days That Changed the World: The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford. Montreal, CA: Black Rose Books. ISBN 9781551642758.

- Petrovsky, Vladimir. 2006. "The Helsinki Process as a Model for Korea." World & I Special Report 2 (1).

- Richmond, Yale. 2004. Cultural Exchange & The Cold War: Raising the Iron Curtain. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271023021.

- Thompson, John M. 2004. Russia and the Soviet Union: An Historical Introduction from the Kievan State to the Present. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813341453.

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- United States Helsinki Commission.

- OSCE Magazine October 2005: celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Helsinki Accords.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.