Difference between revisions of "Ukraine" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) (Ukraine - hist) |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

During the [[Iron Age]], these were followed by the [[Cimmerians]], [[Scythians]], [[Sarmatians]], among other pastoral nomads, along with ancient Greek colonies founded from the sixth century B.C.E. on the north-eastern shore of the [[Black Sea]], and the colonies of [[Tyras]], [[Olbia]], [[Hermonassa]], perpetuated by [[Roman]] and [[Byzantine]] cities until the sixth century C.E. | During the [[Iron Age]], these were followed by the [[Cimmerians]], [[Scythians]], [[Sarmatians]], among other pastoral nomads, along with ancient Greek colonies founded from the sixth century B.C.E. on the north-eastern shore of the [[Black Sea]], and the colonies of [[Tyras]], [[Olbia]], [[Hermonassa]], perpetuated by [[Roman]] and [[Byzantine]] cities until the sixth century C.E. | ||

| − | In the third century C.E., the [[Goths]] arrived in the lands of Ukraine, which they called [[Oium]], named by archaeologists the [[Chernyakhov culture]]. The [[Ostrogoths]] stayed in the area but came under the sway of the [[Huns]] from the 370s | + | In the third century C.E., the [[Goths]] arrived in the lands of Ukraine, which they called [[Oium]], named by archaeologists the [[Chernyakhov culture]]. The [[Ostrogoths]] stayed in the area but came under the sway of the [[Huns]] from the 370s. |

| − | + | ===Kiev culture=== | |

| + | To the north, the [[Kiev culture]] flourished from the third to fifth centuries C.E. It is considered to be the first [[Slavic]] archaeological culture, and was contemporaneous to (and located mostly just to the north of) the multi-ethnic [[Gothic]] kingdom, [[Oium]]. Settlements are found mostly along river banks, frequently either on high cliffs or right by the edge of rivers. The dwellings are semi-subterranean, often square (about four by four meters), with an open hearth in a corner. Most villages consist of just a handful of dwellings. | ||

| − | + | The Huns were defeated at the battle of Nedao in 454. With the power vacuum created with the end of Hunnic and Gothic rule, [[Slavic tribes]], possibly emerging from the remnants of the Kiev culture, began to expand over much of what is now Ukraine during the fifth century, and beyond to the Balkans from the sixth century. | |

| − | The majority of the Bulgar tribes migrated in several directions at the end of the seventh century and the remains of their state was swept by the [[Khazars]], a semi-nomadic people from [[Central Asia]]. The Khazars founded the independent [[Khazar kingdom]] | + | In the seventh century, the territory of modern Ukraine was the core of the state of the [[Bulgars]] (often referred to as [[Old Great Bulgaria]]) who had their capital in the city of [[Phanagoria]]. The majority of the Bulgar tribes migrated in several directions at the end of the seventh century and the remains of their state was swept by the [[Khazars]], a semi-nomadic people from [[Central Asia]]. The Khazars founded the independent [[Khazar kingdom]] near the [[Caspian Sea]] and the [[Caucasus]], which included territory in what is now eastern Ukraine, [[Azerbaijan]], southern [[Russia]], and [[Crimea]]. |

===Golden Age of Kiev=== | ===Golden Age of Kiev=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Kievan Rus en.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Map of the [[Kievan Rus']], eleventh century. | + | [[Image:Kievan Rus en.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Map of the [[Kievan Rus']], eleventh century. |

| − | + | Rus is mentioned for the first time by European chroniclers in 839 C.E. Kievan Rus' comprised several principalities ruled by the interrelated [[Rurikid]] princes. The Kievan state flourished from the ninth to the eleventh centuries under the rulers [[Volodymyr I]] (980-1015), his son [[Yaroslav I the Wise]] (1019-1054), and [[Volodymyr Monomakh]] (1113-1125). Volodymyr I Christianized Rus in 988 c.e., while the other two gave it a legal code. Christianity brought the alphabet, developed by the Macedonian saints Cyril and Methodius. | |

| − | Rus is mentioned for the first time by European chroniclers in 839 C.E. Kievan Rus' | ||

This state laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians, as well as other East Slavic nations. Its capital was [[Kiev]], wrestled from Khazars by [[Askold and Dir]] in about 860. The Kievan Rus' elite initially consisted of [[Varangian]]s from [[Scandinavia]] who later became assimilated into the local Slavic population and gave the Rus' its first powerful dynasty, the [[Rurik Dynasty]]. | This state laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians, as well as other East Slavic nations. Its capital was [[Kiev]], wrestled from Khazars by [[Askold and Dir]] in about 860. The Kievan Rus' elite initially consisted of [[Varangian]]s from [[Scandinavia]] who later became assimilated into the local Slavic population and gave the Rus' its first powerful dynasty, the [[Rurik Dynasty]]. | ||

| − | With the death of [[Mstislav of Kiev]] (1125–1132) the Kievan Rus' | + | With the death of [[Mstislav of Kiev]] (1125–1132) the Kievan Rus' disintegrated into the separate principalities. The thirteenth century Mongol invasion dealt Rus' a final blow. |

===Mongols, Lithuanians and Poles=== | ===Mongols, Lithuanians and Poles=== | ||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

{{legend|lightgrey|Duchy of Courland - Polish Crown fief}} | {{legend|lightgrey|Duchy of Courland - Polish Crown fief}} | ||

{{legend|darkgrey|Livonia - Polish fief}}]] | {{legend|darkgrey|Livonia - Polish fief}}]] | ||

| − | + | The principalities of [[Halych]] and [[Volhynia]]merged into the state of [[Halych-Volynia]], and resisted the Mongols and Tatars to become a Rus bastion through the fourteenth century. A distinguished ruler was Danylo Romanovich, crowned by Pope Innocent IV in 1264, the only Ukrainian king to be thus crowned. | |

| − | After the fourteenth century, Rus fell under foreign domination. Lithuania controlled most of the Ukraine lands except for [[Halych]] and [[Volhynia]], defeated by Poland. The Golden Horde, an outpost of Genghis Khan's empire controlled the southern steppes and the Black Sea coast. The Crimean khanate, an | + | After the fourteenth century, Rus fell under foreign domination. Lithuania controlled most of the Ukraine lands except for [[Halych]] and [[Volhynia]], defeated by Poland. The Golden Horde, an outpost of Genghis Khan's empire, controlled the southern steppes and the Black Sea coast. The Crimean khanate, an Ottoman vassal state, succeeded the Golden Horde from 1475. |

| − | Eventually, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania controlled north-west and central Ukraine. The Grand Duchy adopted the Rus administration and the legal system, while the state language | + | Eventually, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania controlled north-west and central Ukraine. The Grand Duchy adopted the Rus administration and the legal system, while the state language was Old Slavonic, including a great deal of vernacular Ukrainian and Belorussian. From 1386, after a dynastic link with Poland, the Lithuanian elite adopted Roman Catholicism as well as Polish language and customs, while the common people retained allegiance to the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]], increasing social tensions. |

| − | By the 1569 Union of Lublin that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory | + | By the 1569 Union of Lublin, that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory was transferred to the Polish rule. The 1596 Brest-Litovsk Union divided Ukrainians into Orthodox and Uniate Catholics. [[Sigismund III Vasa]] attempted to bring the Orthodox population under the Catholicism through creation of the [[Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church]]. While the upper class increasingly turned to Catholicism, the Ukrainian commoners, deprived of their native protectors among Ruthenian nobility, turned for protection to the [[Cossacks]] who remained fiercely Orthodox. |

| − | From 1569 the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] | + | From 1569 the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] sustained a series of Tatar invasions. The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the eighteenth century. More than three million people, predominantly [[Ukrainians]] but also [[Circassians]], [[Russians]], [[Belarusians]] and [[Poles]], were captured and enslaved during the time of the [[Crimean Khanate]]. |

===The Cossacks=== | ===The Cossacks=== | ||

[[Image:Powrot Kozakow.jpg|thumb|left|350px|"The Return of the Cossacks" oil on canvas, 1894, 61 x 120 cm, painted by Józef Brandt.]] | [[Image:Powrot Kozakow.jpg|thumb|left|350px|"The Return of the Cossacks" oil on canvas, 1894, 61 x 120 cm, painted by Józef Brandt.]] | ||

| − | In the mid of the seventeenth century, a Cossack state, the [[Zaporozhian Sich]], was established by | + | In the mid of the seventeenth century, a Cossack state, the [[Zaporozhian Sich]], was established by Dnieper Cossacks and the Ruthenian peasants fleeing Polish serfdom. Zaporozhian Cossacks, who were based on an island fortress below the Dnipro River rapids, became symbols of Ukrainian national identity. |

| − | Strife between Ukrainians and their Polish overlords, over exploitation of peasants and suppression of the Orthodox church, began in the 1590s, spearheaded by the Cossacks. | + | Strife between Ukrainians and their Polish overlords, over the exploitation of peasants and suppression of the Orthodox church, began in the 1590s, spearheaded by the Cossacks. In 1648, [[Bohdan Khmelnytsky]] led the largest of the Cossack uprisings] against the Commonwealth and the Polish king [[John II Casimir]]. This uprising finally led to a partition of Ukraine between Poland and Russia. Khmelnytsky sought help against the Poles in a treaty with Moscow in 1654. The Muscovites used as a pretext for occupation. [[Left-Bank Ukraine]] was eventually integrated into Russia as the Cossack Hetmanate. |

| − | The hetmanate reached its pinnacle under Ivan Mazepa (1687–1709). Literature, art, architecture (in Cossack baroque style), and learning flourished. Mazepa sought a united Ukrainian state, under the tsar's sovereignty. When Tsar Peter threatened Ukrainian autonomy, Mazepa allied with Charles XII of Sweden and rose against him, to be defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. | + | The hetmanate reached its pinnacle under [[Ivan Mazepa]] (1687–1709). Literature, art, architecture (in Cossack baroque style), and learning flourished. Mazepa sought a united Ukrainian state, under the tsar's sovereignty. When Tsar Peter threatened Ukrainian autonomy, Mazepa allied with Charles XII of Sweden and rose against him, to be defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709. |

===Russian domination=== | ===Russian domination=== | ||

| − | By the end of the eighteenth century, Western Ukrainian | + | By the end of the eighteenth century, Western Ukrainian Galicia was taken over by Austria, while the rest of Ukraine was progressively incorporated into the Russian Empire. Empress Catherine II extended serfdom to the traditionally free Cossack regions and destroyed the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775. Russia repressed any movement towards national identity during the nineteenth century. The Ukrainian language was banned from all but domestic use. |

However, many Ukrainians accepted their fate in the [[Russian Empire]] and some were to achieve a great success there. Many Russian writers, composers, painters and architects of the nineteenth century were of Ukrainian descent. Probably, the most notable was [[Nikolai Gogol]], one of the greatest writers in the [[Russian literature]]. | However, many Ukrainians accepted their fate in the [[Russian Empire]] and some were to achieve a great success there. Many Russian writers, composers, painters and architects of the nineteenth century were of Ukrainian descent. Probably, the most notable was [[Nikolai Gogol]], one of the greatest writers in the [[Russian literature]]. | ||

Revision as of 01:37, 22 July 2007

| Україна Ukrayina Ukraine | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Ще не вмерла України ні слава, ні воля (Ukrainian) Shche ne vmerla Ukrayiny ni slava, ni volya (transliteration) Ukraine's glory has not yet perished, nor her freedom | |||||

| Capital | Kiev (Kyiv) 50°27′N 30°30′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Ukrainian | ||||

| Government | Semi-presidential system | ||||

| - President | Viktor Yushchenko | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Viktor Yanukovych | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union | ||||

| - Declared | August 24 1991 | ||||

| - Referendum | December 1 1991 | ||||

| - Finalized | December 25 1991 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 603,700 km² (44th) 233,090 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 7% | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2007 estimate | 46,299,874 | ||||

| - 2001 census | 48,457,102 | ||||

| - Density | 77/km² 199/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $355.8 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $8,000 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $81.53 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $1,760 | ||||

| HDI (2004) | |||||

| Currency | Hryvnia (UAH)

| ||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ua | ||||

| Calling code | +380 | ||||

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe, formerly a part of the Soviet Union, bordering Russia, Romania and the Black Sea.

From at least the ninth century, the territory of present-day Ukraine was a centre of medieval East Slavic civilization forming the state of Kievan Rus. After a brief period of independence (1917–1921) following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Ukraine became one of the founding Republics of the Soviet Unions in 1922. Ukraine and became independent again after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991.

The Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986, and subsequent radiation contamination, along with economic woes, have been blamed for a population decline from 51 million in 1989, to 48.5 million in 2001.

Geography

The Ukrainian word Ukrayina stems from the Old Slavic root kraj, meaning "edge" or "borderland", and krayina means "country". In English, the country is sometimes referred to as the Ukraine, similar to the Netherlands, or the Congo. However, usage without the article is now more frequent, especially since the country's independence.

Ukraine has a strategic position in Eastern Europe, bordering the Black Sea and Sea of Azov in the south, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary in the west, Belarus in the north, Moldova and Romania in the south-west and Russia in the east. Some claim the geographical centre of Europe is near the small town of Rakhiv, in western Ukraine.

With an area of 233,074 square miles (603,700 square kilometres), Ukraine is the second largest country in Europe (after the European part of Russia), and slightly smaller than Texas.

The Ukrainian landscape consists of the Polissya and Volyn northern forests, the central forest steppes, the Donetsk eastern uplands, which are up to 1600 feet (500 meters) above sea level, and the coastal lowlands and steppes along the Black and Azov seas. The Carpathian Mountains in the west reach 6760 feet (2061 meters) at Mount Hoverla. Roman-Kosh in the Crimean peninsula reaches 5061 feet (1543 meters.) Alpine meadows are another interesting feature.

Ukraine has a mostly temperate continental climate, with a more Mediterranean climate on the southern Crimean coast. The average temperature in January (winter) is 26°F (-3°C) in the southwest and 18°F (-8°C) in the northeast. The average in July (summer) is 73°F (23°C) in the southeast and 64°F (18°C) in the northwest.

Precipitation is highest in the west and north. Winters vary from cool along the Black Sea to cold farther inland. Summers are warm across the greater part of the country, but generally hot in the south.

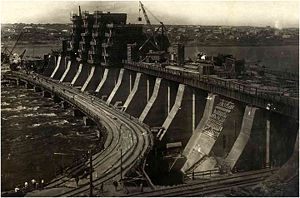

The main rivers flow northwest to southeast to empty into the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. The Dnieper River is the longest, with hydroelectric dams, reservoirs, and numerous tributaries, dominating central Ukraine. The Southern Bug with its tributary, the Inhul, flows into the Black Sea. To the west and southwest is the Dniester. The middle course of the Donets]], a tributary of the Don, flows through the south-east. To the southwest the delta of the Danube forms the border with Romania.

Three zones of vegetation appear from north to south: the Polissya (woodland and marsh), the forest-steppe, and the Steppe. The Polissya zone has oak, elm, birch, hornbeam, ash, maple, pine, linden, alder, poplar, willow, and beech. In mountainous areas, the lower slopes are covered with mixed forests, the intermediate slopes have pine forests, with alpine meadows at higher altitudes.

Ukraine’s fauna is diverse. Predators include the wolf, fox, wildcat, and marten, and hoofed animals include the roe deer, wild pig, elk and mouflon (a wild sheep). Rodents include gophers, hamsters, jerboas, and field mice. Birds include black and hazel grouse, owl, gull, and partridge, as well as wild goose, duck, and stork. Fish include pike, carp, bream, perch, sturgeon, and sterlet.

Natural resources comprise iron ore, coal, manganese, natural gas, oil, salt, sulfur, graphite, titanium, magnesium, kaolin, nickel, mercury, timber, and arable land.

The country has significant environmental problems, especially those resulting from the Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster in 1986, and subsequent radiation contamination in the northeast. Other issues include inadequate supplies of potable water, air and water pollution, and deforestation. Conservation of natural resources is a stated high priority, although implementation suffers from a lack of financial resources.

The historic city of Kiev is the capital and the largest city, and is located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper river. In 2005 Kiev had 2,660,401 inhabitants, and this figure continues to grow. Kiev is an important industrial, scientific, educational and cultural center of Eastern Europe. It is home to many high-tech industries, higher education institutions and world-famous historical landmarks. The city has an extensive infrastructure and highly developed system of public transport, including the Kiev Metro.

History

Chalcolithic (Copper Age) people populated what became western Ukraine, and the Sredny Stog culture (4500-3500 B.C.E.) was situated north of the Sea of Azov. The early Bronze Age Yamna culture (3600-2300 B.C.E.) occupied the Bug-Dniester-Ural region, leaving hundreds of crude stone stela, followed by the Catacomb culture in the third millennium B.C.E.

During the Iron Age, these were followed by the Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, among other pastoral nomads, along with ancient Greek colonies founded from the sixth century B.C.E. on the north-eastern shore of the Black Sea, and the colonies of Tyras, Olbia, Hermonassa, perpetuated by Roman and Byzantine cities until the sixth century C.E.

In the third century C.E., the Goths arrived in the lands of Ukraine, which they called Oium, named by archaeologists the Chernyakhov culture. The Ostrogoths stayed in the area but came under the sway of the Huns from the 370s.

Kiev culture

To the north, the Kiev culture flourished from the third to fifth centuries C.E. It is considered to be the first Slavic archaeological culture, and was contemporaneous to (and located mostly just to the north of) the multi-ethnic Gothic kingdom, Oium. Settlements are found mostly along river banks, frequently either on high cliffs or right by the edge of rivers. The dwellings are semi-subterranean, often square (about four by four meters), with an open hearth in a corner. Most villages consist of just a handful of dwellings.

The Huns were defeated at the battle of Nedao in 454. With the power vacuum created with the end of Hunnic and Gothic rule, Slavic tribes, possibly emerging from the remnants of the Kiev culture, began to expand over much of what is now Ukraine during the fifth century, and beyond to the Balkans from the sixth century.

In the seventh century, the territory of modern Ukraine was the core of the state of the Bulgars (often referred to as Old Great Bulgaria) who had their capital in the city of Phanagoria. The majority of the Bulgar tribes migrated in several directions at the end of the seventh century and the remains of their state was swept by the Khazars, a semi-nomadic people from Central Asia. The Khazars founded the independent Khazar kingdom near the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus, which included territory in what is now eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, southern Russia, and Crimea.

Golden Age of Kiev

[[Image:Kievan Rus en.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Map of the Kievan Rus', eleventh century. Rus is mentioned for the first time by European chroniclers in 839 C.E. Kievan Rus' comprised several principalities ruled by the interrelated Rurikid princes. The Kievan state flourished from the ninth to the eleventh centuries under the rulers Volodymyr I (980-1015), his son Yaroslav I the Wise (1019-1054), and Volodymyr Monomakh (1113-1125). Volodymyr I Christianized Rus in 988 C.E., while the other two gave it a legal code. Christianity brought the alphabet, developed by the Macedonian saints Cyril and Methodius.

This state laid the foundation for the national identity of Ukrainians, as well as other East Slavic nations. Its capital was Kiev, wrestled from Khazars by Askold and Dir in about 860. The Kievan Rus' elite initially consisted of Varangians from Scandinavia who later became assimilated into the local Slavic population and gave the Rus' its first powerful dynasty, the Rurik Dynasty.

With the death of Mstislav of Kiev (1125–1132) the Kievan Rus' disintegrated into the separate principalities. The thirteenth century Mongol invasion dealt Rus' a final blow.

Mongols, Lithuanians and Poles

[[Image:Rzeczpospolita2nar.png|thumb|250px|left|In the centuries following the Mongol invasion, much of Ukraine was controlled by Lithuania (from the fourteenth century on) and since the Union of Lublin (1569) by Poland as seen at this outline of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as of 1619 ██ Kingdom of Poland ██ Duchy of Prussia - Polish fief ██ Grand Duchy of Lithuania ██ Duchy of Courland - Polish Crown fief ██ Livonia - Polish fief]] The principalities of Halych and Volhyniamerged into the state of Halych-Volynia, and resisted the Mongols and Tatars to become a Rus bastion through the fourteenth century. A distinguished ruler was Danylo Romanovich, crowned by Pope Innocent IV in 1264, the only Ukrainian king to be thus crowned.

After the fourteenth century, Rus fell under foreign domination. Lithuania controlled most of the Ukraine lands except for Halych and Volhynia, defeated by Poland. The Golden Horde, an outpost of Genghis Khan's empire, controlled the southern steppes and the Black Sea coast. The Crimean khanate, an Ottoman vassal state, succeeded the Golden Horde from 1475.

Eventually, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania controlled north-west and central Ukraine. The Grand Duchy adopted the Rus administration and the legal system, while the state language was Old Slavonic, including a great deal of vernacular Ukrainian and Belorussian. From 1386, after a dynastic link with Poland, the Lithuanian elite adopted Roman Catholicism as well as Polish language and customs, while the common people retained allegiance to the Eastern Orthodox Church, increasing social tensions.

By the 1569 Union of Lublin, that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory was transferred to the Polish rule. The 1596 Brest-Litovsk Union divided Ukrainians into Orthodox and Uniate Catholics. Sigismund III Vasa attempted to bring the Orthodox population under the Catholicism through creation of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. While the upper class increasingly turned to Catholicism, the Ukrainian commoners, deprived of their native protectors among Ruthenian nobility, turned for protection to the Cossacks who remained fiercely Orthodox.

From 1569 the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth sustained a series of Tatar invasions. The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the eighteenth century. More than three million people, predominantly Ukrainians but also Circassians, Russians, Belarusians and Poles, were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate.

The Cossacks

In the mid of the seventeenth century, a Cossack state, the Zaporozhian Sich, was established by Dnieper Cossacks and the Ruthenian peasants fleeing Polish serfdom. Zaporozhian Cossacks, who were based on an island fortress below the Dnipro River rapids, became symbols of Ukrainian national identity.

Strife between Ukrainians and their Polish overlords, over the exploitation of peasants and suppression of the Orthodox church, began in the 1590s, spearheaded by the Cossacks. In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the largest of the Cossack uprisings] against the Commonwealth and the Polish king John II Casimir. This uprising finally led to a partition of Ukraine between Poland and Russia. Khmelnytsky sought help against the Poles in a treaty with Moscow in 1654. The Muscovites used as a pretext for occupation. Left-Bank Ukraine was eventually integrated into Russia as the Cossack Hetmanate.

The hetmanate reached its pinnacle under Ivan Mazepa (1687–1709). Literature, art, architecture (in Cossack baroque style), and learning flourished. Mazepa sought a united Ukrainian state, under the tsar's sovereignty. When Tsar Peter threatened Ukrainian autonomy, Mazepa allied with Charles XII of Sweden and rose against him, to be defeated in the Battle of Poltava in 1709.

Russian domination

By the end of the eighteenth century, Western Ukrainian Galicia was taken over by Austria, while the rest of Ukraine was progressively incorporated into the Russian Empire. Empress Catherine II extended serfdom to the traditionally free Cossack regions and destroyed the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775. Russia repressed any movement towards national identity during the nineteenth century. The Ukrainian language was banned from all but domestic use.

However, many Ukrainians accepted their fate in the Russian Empire and some were to achieve a great success there. Many Russian writers, composers, painters and architects of the nineteenth century were of Ukrainian descent. Probably, the most notable was Nikolai Gogol, one of the greatest writers in the Russian literature.

World War I

During World War I Austro-Hungarian authorities subjected Ukrainians in Galicia who sympathized with Russia to repression. Over 20,000 supporters of Russia were arrested and placed in an Austrian concentration camp in Talerhof, Styria, and in a fortress at Terezín (now in the Czech Republic).

When World War I and the October Revolution in Russia shattered the Austrian and Russian empires, Ukrainians were caught in the middle. Between 1917 and 1918, several separate Ukrainian republics manifested independence, the Tsentral'na Rada, the Hetmanate, the Directorate, the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian People's Republic.

In this time, most of the resistance against the Austro-Germans and the Red Army was made by the army of Nestor Makhno, who led an Anarchist revolution in this period, the Makhnovism.

With the defeat in the Polish-Ukrainian War and then the failure of the Józef Piłsudski's and Symon Petlura's Kiev Offensive, by the end of the Polish-Soviet War after the Peace of Riga in March 1921, the western part of Galicia had been incorporated into Poland, and the larger, central and eastern part became part of the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Despite the turbulence, this period saw a resurgence of Ukrainian-language publication, which had been controversial in Austro-Hungary, and persecuted in the Russian Empire. The Hetmanate, installed by Germany while overthrowing the government of the UNR conducted state policies directed at bolstering the Ukrainian culture and education. Among the Bolsheviks, national identity was controversial, but the so-called Kiev faction pushed for Ukrainization as well.

Early Soviet years

The Ukrainian national idea lived on during the early-Soviet years and the Ukrainian culture and language enjoyed a revival as the “Ukrainization” became a local implementation of the Soviet-wide "indigenization" policy whose gains were sharply reversed by the early-1930s policy changes.

Ukraine saw its share of Soviet industrialization starting from the late 1920s and the republic's industrial output quadrupled in the 1930s. However, the industrialization had a heavy cost for the peasantry, demographically a backbone of the Ukrainian nation. To satisfy the state's need for increased food supplies and finance industrialization, Stalin instituted a program of collectivization of agriculture as the state combined the peasants' lands and animals into collective farms and enforcing the policies by the regular troops and secret police. Those who resisted were arrested and deported and the increased production quotas were placed on the peasantry.

The collectivization had a devastating effect on agricultural productivity. As the members of the collective farms were not allowed to receive any grain until the unachievable quotas were met, the starvation became widespread. Millions starved to death in a famine, known as the Holodomor.Available data is inconclusive as the Soviet government actively denied the existence of the famine. Therefore, precise calculations and estimates vary.

The times also coincided with the Soviet assault on the national political and cultural elite often accused in "nationalist deviations" as the Ukrainization. These policies were reversed at the turn of the decade. Two waves of purges (1929–1934 and 1936–1938) resulted in the elimination of four fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite.

World War II

During World War II, some elements of the Ukrainian nationalist underground fought both Nazi and Soviet forces, forming the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in 1942, while other Ukrainians initially collaborated with the Nazis, having been ignored by all other powers. In 1941 the German invaders and their Axis allies initially advanced against desperate but unsuccessful efforts of the Red Army. In the encirclement battle of Kiev, the city was acclaimed by the Soviets as a "Hero City", for the fierce resistance of the Red Army and of the local population. More than 650,000 Soviet males between the ages of 15-50 were taken captive.

Initially, many Ukrainians received the Germans as liberators, especially in western Ukraine, that the Soviets occupied in 1939. However, German rule in the occupied territories eventually aided the Soviet cause. Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population of Ukrainian territories' dissatisfaction with Soviet political and economic policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, deported others (mainly Ukrainians) to work in Germany, and began a systematic depopulation of Ukraine to prepare it for German colonization, which included a food blockade on Kiev. Under these circumstances, most people living on the occupied territory passively or actively opposed the Nazis.

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated between five and eight million, including over half a million Jews killed by the Einsatzgruppen, sometimes with the help of local collaborators. Of the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis, about a quarter (2.7 million) were ethnic Ukrainians. Ukraine is distinguished as one of the first nations to fight the Axis powers in Carpatho-Ukraine, and one that saw some of the greatest bloodshed during the war.

Resistance

The republic was heavily damaged by the war, and it required significant efforts to recover. The situation was worsened by a man-made famine in 1946–47, when the Soviet authorities forcibly confiscated grain crops, ignoring drought conditions of 1946. Collected grain was distributed to the other regions of Soviet Union, and on the top, 2.5 million tonnes were exported abroad. In Ukraine about one million people, predominantly in rural areas, died from the famine.

In the Western Ukraine, Ukrainians continued to resist Soviet rule, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, formed in World War II to fight both Soviets and Nazis, continued to fight the USSR into the 1950s. Using guerrilla war tactics, the insurgents assassinated Soviet party leaders, NKVD and military officers. In particular, due to the resistance, the 1946-47 famine was much less severe in West Ukraine than in other Ukrainian regions.

Following the death of Stalin in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader of USSR. Being the First Secretary of Communist Party of Ukrainian SSR in 1938-49, Khrushchev played a role in Stalin's repressions, the liberation of Ukraine from the Nazis, organization of the man-made famine in 1946-47 and suppression of resistance in West Ukraine. But after taking the power, he found it best to propagandize the friendship between the Ukrainian and Russian nations. In 1954, the 300th anniversary of the Treaty of Pereyaslav was widely celebrated, and in particular, the Crimea was transferred from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.

In the times of Khrushchev Thaw of 1960s, there were dissident movements in Ukraine by such prominent figures as Vyacheslav Chornovil, Vasyl Stus, Levko Lukyanenko. As in the other regions of USSR, the movements were quickly suppressed.

In the 1970s, the new Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev was gradually concentrating on power. In 1972, the First Secretary of Communist Party of Ukraine Petro Shelest lost his position, as he was seen as being "too independent" by the government in Moscow, and was replaced by Volodymyr Shcherbytsky.

The rule of Shcherbytsky was characterized by the expanded policies of Russification. At the same time he used his influence as the First Secretary of CPU, and a Politburo member for over 25 years, to advocate economic interests of Ukraine within the USSR.

Chernobyl disaster

On April 26, 1986, a nuclear reactor exploded at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. The disaster was the product of a flawed reactor design coupled with serious mistakes made by the plant operators in the context of a system where training was minimal. Large areas of Belarus, Ukraine, Russia and beyond were contaminated in varying degrees. Around 150,000 people were evacuated from the contaminated area, and 300,000–600,000 took part in the clean-up. By the year 2000, about 4000 cases of thyroid cancer had been diagnosed in exposed children. After the accident a 30km exclusion zone was established around the power plant. A new city, Slavutych, was built outside the exclusion zone to house and support the employees of the plant.

Independence

The wave of [[Soviet Premier Mihail Gorbachev’s “perestroika” economic restructuring came to Ukraine only in 1988–89. It was hindered initially by Shcherbytsky and party heads, and the economic slowdown and product shortages were initially not as severe in Ukraine as in the other regions of USSR.

In 1989, the national movement "People's Movement of Ukraine", known in short as Rukh was formed. In the elections to the parliament of republic, which were held in March of 1990, Rukh obtained overwhelming support in West Ukraine, as well as in the cities of Kiev and Kharkiv.

In January of 1990, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians organized a human chain for independence in memory of 1919 unification of Ukrainian People's Republic and West Ukrainian National Republic. On July 16, 1990 the new parliament adopted the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine, establishing the principles of the self-determination, democracy, political, and economic independence, and the priority of Ukrainian law on the Ukrainian territory over Soviet law. A month earlier, a similar declaration was adopted by the parliament of Russian SFSR. It opened a period of confrontation between the central Soviet, and new republican authorities.

In March of 1991, central Soviet authorities organized a referendum, asking people to express the desire to live in "renewed" Soviet Union. The Ukrainian parliament added a second question, asking Ukrainian citizens the desire to live in the Soviet Union on the principles established in the Declaration of State Sovereignty. The citizens of Ukraine responded positively to both questions.

In August of 1991, the conservative Communist leaders of Soviet Union attempted a coup to remove Gorbachev and to restore Communist party power. After the attempt failed, on August 22, 1991, the Ukrainian parliament adopted the Act of Independence of Ukraine in which the parliament declared Ukraine as independent democratic state.

A referendum and the first presidential elections took place on December 1, 1991. That day, more than 90 percent of Ukrainians expressed their support for the Act of Independence, and they elected the chairman of the parliament, Leonid Kravchuk to serve as the first president.

At the Belavezha Accords on December 8, followed by the Alma Ata meeting on December 21, the leaders of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine, formally dissolved the Soviet Union, and formed the Commonwealth of Independent States.

Recession

Private property rights were reinstated from 1991, collective farms were abolished in 2000, and peasants received land titles. Initially viewed as having more favorable economic conditions than other regions of the Soviet Union, Ukraine soon went into a deep economic slowdown, losing 60 percent of its Gross domestic product from 1991-1999, and sustaining five-digit inflation rates. Dissatisfied with the economic conditions, as well as crime and corruption, Ukrainians protested and went on strikes. In 1994, the President Kravchuk lost an early presidential election to former Prime-Minister Leonid Kuchma.

Under Kuchma, who served two terms as the President, the Ukrainian economy stabilized by the end of 1990s, and ever since 2000 it enjoyed a steady economic growth averaging approximately seven percent annually. A new constitution was adopted in 1996, which turned Ukraine into a semi-presidential republic, and established a stable political system. Kuchma was, however, criticized by opponents for concentrating too much of power in his office, corruption, transferring public property into hands of loyal oligarchs, discouraging free speech, and election fraud.

The first National Space Agency of Ukraine astronaut to enter space under the Ukrainian flag was Leonid Kadenyuk on May 13, 1997. Ukraine became an active participant in scientific space exploration and remote sensing missions. In a period from 1992 to 2007 Ukraine has launched six Ukrainian-built satellites, and 97 launch vehicles.

Orange revolution

In 2004, Victor Yanukovich, then Prime Minister, was declared the winner of the presidential elections, which had allegedly been rigged. Victor Yuschenko challenged the results and led the peaceful Orange Revolution, which brought him and Yulia Tymoshenko to power, while casting Viktor Yanukovych in opposition.

The 2006 parliamentary election resulted in a government formed by the "Anti-Crisis Coalition" including the Party of Regions, Communist Party, and Socialist Party of Ukraine. The latter party switched from the "Orange Coalition" with Our Ukraine, and the Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc. The new coalition nominated Viktor Yanukovych for the post of Prime Minister. Yanukovich once again became the Prime Minister, while the leader of Socialist Party, Oleksander Moroz, managed to secure the chairman of parliament position.

Government and politics

Ukraine is a republic under a semi-presidential system with separate legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Ukraine in 2006 underwent an extensive constitutional reform that has changed the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches and their relationship to the president. A reform to local self-government has been suggested, but is yet to be formally approved.

According to the constitution the president is the head of state, and is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. The last presidential elections were held in 2004. Viktor Yushchenko has been president since January 23, 2005. Although the constitutional reform substantially reduced presidential authority, the president continued to wield significant power, partially due to a strong tradition of central authority in the country.

The Verkhovna Rada, a unicameral parliament of 450 seats amends the Constitution of Ukraine, drafts laws, ratifies international treaties, appoints a number of officials, and elects judges. Members are allocated on a proportional basis to those parties that gain three percent or more of the national electoral vote, to serve five-year terms. Elections were last held on March 26, 2006. Ukraine has a large number of political parties, many of which have tiny memberships and are unknown to the general public. Small parties often join in multi-party coalitions (electoral blocks) for the purpose of participating in parliamentary elections. Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years and over.

The Verkhovna Rada is primarily responsible for the formation of the executive branch, the Cabinet of Ministers, which is headed by the prime minister, who is head of government. Viktor Yanukovych has been prime minister since August 4, 2006. The prime minister selects the cabinet of ministers. Constitutional reform has increased the authority of the Verkhovna Rada over the selection and oversight of the executive branch.

The judiciary comprises a constitutional court, a supreme court, a high arbitration court , a high administrative court, regional, military, and specialized courts of appeal, local district courts, and military garrison courts. The constitution provides for trials by jury, although by 2007, this had not been implemented. The legal system is based on civil law system.

Local self-government is officially guaranteed. Local councils and city mayors are popularly elected and exercise control over local budgets. The president appoints the heads of regional and district administrations.

Reform fall-out

A substantial constitutional reform introduced in the beginning of 2006 were meant to transform the Ukrainian state from a presidential republic to a mixed parliamentary-presidential republic. However, the amendments created an environment for conflict between the president and the parliamentary coalition. The political life of Ukraine during the 2006-07 year was a constant power struggle between the president and the prime minister, aggravated by the fact that the president and the prime minister represent the opposite parts of the political spectrum and differ on foreign and the internal policy. The president Viktor Yushchenko accuses the coalition of trying to usurp the powers he preserved in the reform, while the coalition alleges the president is unwilling to accept the consequences of the reform and is trying to regain his former powers.

Crowds of about 70,000 gathered on Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the central square of Kiev, and supported the dismissal of parliament, with 20,000 supporting Yanukovych's plan to keep the parliament together. On April 3, 2007, President Yushchenko dissolved the Ukrainian parliament and ordered an early election to be held May 27, 2007. The Verkhovna Rada called an emergency session and voted against Yuschenko's decree (255 votes in favor; opposition didn't participate). A group of members of the parliament took the case to the Constitutional Court of Ukraine, challenging the validity of the president's decree, but the court closed the case without opinion. A political struggle ensued between the parliamentary coalition and the opposition. Yushchenko and Yanukovych agreed to reschedule parliamentary elections for September 30, 2007.

Ukraine is subdivided into 24 oblasts (provinces) and one autonomous republic (avtonomna respublika), Crimea. Additionally, two cities (misto), Kiev and Sevastopol, have a special legal status. The oblasts are subdivided into 494 raions (districts).

International relations

Ukraine considers Euro-Atlantic integration its primary foreign policy objective, but in practice balances its relationship with Europe and the United States with strong ties to Russia. The European Union's Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with Ukraine went into force in 1998. The EU Common Strategy toward Ukraine, issued in 1999, recognizes Ukraine's long-term aspirations but does not discuss association. In 1992, Ukraine joined the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe—OSCE), and the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. Ukraine also has a close relationship with NATO and has declared interest in eventual membership. It is the most active member of the Partnership for Peace (PfP). President Viktor Yushchenko said he want that Ukraine should join the EU in future.

Ukraine has especially close ties with Russia and Poland. Relations with Russia are complicated by energy dependence and by payment arrears. However, relations have improved with the 1998 ratification of the bilateral Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation. Also, the two sides have signed a series of agreements on the final division and disposition of the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet that have helped to reduce tensions. Ukraine became a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in 1991, but in 1993 it refused to endorse a draft charter strengthening political, economic, and defense ties among CIS members. Ukraine was a founding member of GUAM (Georgia-Ukraine-Azerbaijan-Moldova).

In 1999-2001, Ukraine served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. Soviet Ukraine joined the United Nations in 1945 as one of the original members following a Western compromise with the Soviet Union, which had asked for seats for all 15 of its union republics. Ukraine has consistently supported peaceful, negotiated settlements to disputes. Ukraine also has made a substantial contribution to UN peacekeeping operations since 1992.

Military

After the collapse of Soviet Union, Ukraine inherited a one-million-man military force on its territory, equipped with the third largest nuclear weapon arsenal in the world. In May of 1992, Ukraine signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) in which the country agreed to give up all nuclear weapons, and to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear weapon state. Ukraine ratified the treaty in 1994, and by 1996 the country became free of nuclear weapons.

Ukraine also reduced conventional weapons. It signed the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, and reduced the army to 300,000 soldiers. The country plans to convert the mostly conscript, army into a professional army.

Following independence, Ukraine declared itself to be a neutral state. The country had a limited military partnership with Russia and other CIS countries, as well as, since 1994, it established a partnership with NATO. In 2000s Ukraine was leaning toward NATO, and a NATO-Ukraine Action Plan signed in 2002 led to deeper cooperation. In August of 2006, the leading political parties agreed that the question of joining NATO should be answered by a national referendum.

Economy

The economy of Ukraine is an emerging free market, that underwent major fluctuations during the 1990s, including hyperinflation and drastic falls in economic output. As part of the former Soviet Union, the Ukrainian republic was far and away the most important economic component, after Russia, producing about four times the output of the next-ranking republic. Its fertile black soil generated more than one-fourth of Soviet agricultural output, and its farms provided substantial quantities of meat, milk, grain, and vegetables to other republics. Likewise, its diversified heavy industry supplied the unique equipment (for example, large diameter pipes) and raw materials to industrial and mining sites (vertical drilling apparatus) in other regions of the former USSR.

Shortly after independence was ratified in December 1991, the Ukrainian Government liberalized most prices and erected a legal framework for privatization, but widespread resistance to reform within the government and the legislature soon stalled reform efforts and led to some backtracking. Output by 1999 had fallen to less than 40 percent of the 1991 level. Loose monetary policies pushed inflation to hyperinflationary levels in late 1993. The prices stabilized only after the introduction of new currency, hryvnia in 1996.

Ukraine's dependence on Russia for energy supplies, and the lack of significant structural reform, has made the Ukrainian economy vulnerable to external shocks. Ukraine depends on imports to meet about three-fourths of its annual oil and natural gas requirements. A dispute with Russia over pricing in late 2005 and early 2006 led to a temporary gas cut-off; Ukraine concluded a deal with Russia in January 2006 that almost doubled the price Ukraine pays for Russian gas, and could cost the Ukrainian economy $1.4-2.2 billion.

Ukrainian Government officials eliminated most tax and customs privileges in a March 2005 budget law, bringing more economic activity out of Ukraine's large shadow economy, but more improvements are needed, including fighting corruption, developing capital markets, and improving the legislative framework for businesses. Reforms in the more politically sensitive areas of structural reform and land privatization are still lagging. Outside institutions - particularly the IMF - have encouraged Ukraine to quicken the pace and scope of reforms. In its efforts to accede to the World Trade Organization (WTO), Ukraine passed more than 20 laws in 2006 to bring its trading regime into consistency with WTO standards.

GDP growth was seven percent in 2006, up from 2.4 percent in 2005 thanks to rising steel prices worldwide and growing consumption domestically. Although the economy is likely to expand in 2007, long-term growth could be threatened by the government's plans to reinstate tax, trade, and customs privileges and to maintain restrictive grain export quotas.

The World Bank classifies Ukraine as a lower middle-income state. For 2006, the Index of Economic Freedom of Ukraine was 3.24, a rank 99 amongst 157 states. Some significant issues are underdeveloped infrastructure and transportation, corruption and bureaucracy, and a lack of modern-minded professionals - despite the large number of universities. But the rapidly growing Ukrainian economy has a very interesting emerging market with a relatively big population, and large profits associated with the high risks.

The Ukrainian stock market grew up 10 times between 2000 and 2006, including the tremendous 341 percent growth in 2004. Growing sectors of the Ukrainian economy include the IT Outsourcing market, which has been growing at over 100 percent per annum.

Exports totalled $38.88-billion in 2006. Export commodities included ferrous and non-ferrous metals, fuel and petroleum products, chemicals, machinery and transport equipment, and food products. Export partners included Russia 22.1 percent, Turkey percent, and Italy 5.6 percent. Imports totalled $44.11-billion. Import commodities included energy, machinery and equipment, and chemicals. Import partners included Russia 35.5 percent, Germany 9.4 percent, Turkmenistan 7.4 percent, and China 5 percent.

Per capita GDP (purchasing power parity) was $8000 in 2006, or ranked 86th on the IMF list of 179 nations. Officially registered unemployment was 2.7 percent, although there was a large number of unregistered or under-employed workers. The International Labor Organization calculated that Ukraine's real unemployment level is 6.7 percent in 2006. Twenty nine percent of the population was below the poverty line in 2003.

Demographics

Ukraine’s population was 46,710,816 in 2006. The industrial regions in the east and south-east are the most heavily populated, and about 67.2 percent of the population lives in urban areas. Significant migration took place in the first years of Ukrainian independence. More than one million people moved into Ukraine in 1991-1992, mostly from the other former Soviet republics. In total, between 1991 and 2004, 2.2 million immigrated to Ukraine (among them, 2.0 million came from the other former Soviet Union states), and 2.5 million emigrated from Ukraine (among them, 1.9 million moved to the rest of former Soviet Union republics).

In the context of low salaries and unemployment within Ukraine, labor emigration became a mass phenomenon at the end of the 1990s. Although estimates vary, approximately two to three million Ukrainian citizens are currently working abroad, many illegally, in construction, service, housekeeping, and agriculture industries. Moreover, a significant number of women from Ukraine had been dragged into prostitution and sex slavery in foreign lands, mainly Western Europe and Turkey. Life expectancy at birth was 70.0 years for the total population in 2006.

Ethnicity

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, ethnic Ukrainians make up 77.8 percent of the population. Other significant ethnic groups are Russians (17.3 percent), Belarusians (0.6 percent), Moldovans (0.5 percent), Crimean Tatars (0.5 percent), Bulgarians (0.4 percent), Hungarians (0.3 percent), Romanians (0.3 percent), Poles (0.3 percent), Jews (0.2 percent), Armenians (0.2 percent), Greeks (0.2 percent) and Tatars (0.2 percent).

Romanians and Moldavians are concentrated mainly in Chernivtsi, Odessa, Zakarpattia and Vinnytsia oblasts. Jews played a very important role in Ukrainian cultural life, especially in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century.

Religion

The dominant religion in Ukraine is Eastern Orthodox Christianity, which is split between three Church bodies: Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Kiev Patriarchate, and Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

A distant second is the Eastern Rite Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, which practices a similar liturgical and spiritual tradition as Eastern Orthodoxy, but is in communion with the See of Peter and recognizes the primacy of the Pope as head of the Church.

There are 879 Catholic communities, and 499 clergy members serving the some one million Roman Catholics in Ukraine. The group forms some 2.19 percent of the population and consists mainly of ethnic Poles, living predominantly in the western regions of the country.

Protestant Christians form some 2.19 percent of the population. Protestant numbers have grown greatly since Ukrainian independence. The Evangelical Baptist Union of Ukraine is the largest group, with more than 300,000 members and about 3000 clergy members. Other groups include Calvinists, Lutherans, Methodists, Seventh-day Adventists and others.

The Jewish community is a tiny fraction of what it was before World War II, but Jews still form some 0.63 percent of the population. A 2001 census indicated 103,600 Jews, although community leaders claimed that the population could be as large as 300,000. Most Ukrainian Jews are Orthodox, and there is a small Reform population.

There are an estimated 500,000 Muslims in Ukraine, some 320,000 on the Crimean Peninsula. Most Ukrainian Muslims are Crimean Tatars. In addition, some 50,000 foreign-born Muslims live in Kiev.

In addition, 29 Krishna Consciousness communities and 47 Buddhist communities were registered in the country (as of January 1, 2006).

Language

Ukrainian is the only official language. It is an Indo-European language of the Eastern Slavic group, and uses the Cyrillic alphabet. Contemporary literary Ukrainian developed in the eighteenth century from the Poltava and Kiev dialects. Russian, which was a de facto official language in the Soviet Union, is widely spoken, especially in eastern and southern Ukraine. According to the census, 67.5 percent of the population declared Ukrainian as their native language and 29.6 percent declared Russian.

It is sometimes difficult to determine the extent of the two languages, since many people use a Surzhyk (a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian where the vocabulary is often combined with Ukrainian grammar and pronunciation) while claiming in surveys that they speak Russian or Ukrainian (most of them are able to speak both literary languages though). Besides, some ethnic Ukrainians, while calling Ukrainian their “native” language, use Russian more frequently in their daily lives.

The government follows a policy of Ukrainization—the increase of Ukrainian language, generally at the expense of Russian. This takes the form of use of Ukrainian in various spheres that are under government control, such as schools, government offices, and some media. This is even done in areas which are largely Russian-speaking. However, in non-government areas of life, the language of convenience (usually Russian) is used.

Nowadays Yiddish, the Ukrainian Jews' traditional language, is only used by a small number of older people.

Men and women

Although Ukrainian labor laws guarantee equal opportunity, few women work at higher levels of government and management, and numerous women work in manual and trade jobs. Teachers and nurses are mostly women, while school administrators and physicians are mostly men. Women are welcome as secretaries or subordinates but not as colleagues or competitors. Under Ukrainian agricultural tradition, men were responsible for tilling the fields and for raising their sons, while women were housekeepers who raised their daughters.

Marriage and the family

Young people chose mates at social events, and parental approval is sought.. The parents organize and finance the wedding, which displays the family's social status. Most weddings have civil and religious ceremonies. The domestic unit is a single family, and elderly parents eventually lived with the child who inherited the family home. Chronic housing shortages meant many young couples live with their parents in close quarters, often causing family strife. The Ukrainian Catholic Church prohibits divorce while the Orthodox Church discourages it. Ukrainian inheritance customs meant sons and daughters inherited parents' property equally.

- Before the wedding, the groom goes with his friends to the bride's house and bargains with "money' to get a bride from her family.

- When leaving the church, the bride carries a basket of candies or sweets to throw to children and the crowd

- The groom carries her down any stairs

- At the reception, the bride dances with each of the unmarried women present, and places a special veil on each of them. This veil symbolises that they are still pure, but that the bride hopes they will get married soon. She also throws a bunch of flowers and the girl who catches it first will likely be the next to marry.

Ukrainian women prefer to care for their children. Paid maternity leave is available for up to one year and unpaid leave of up to three years. Grandparents care for grandchildren, especially in lower-income families. Ancient beliefs persist. A baby's hair is not cut until the first birthday, and safety pins are placed inside a child's clothing to ward off evil.

Education

Ukraine's educational system has produced a high literacy rate. Of the total population in 2001, 99.4 percent age 15 and over can read and write. Education is compulsory from the age of seven, while many children attend certain pre-school courses at six.

The Ukraine education system can be divided into three stages. “Younger school” is grades one to three (few schools offer grade four). Grades five to eight are usually referred to as “middle school”, while nine to 12 are “older school”. At grade 12, which is usually around the age of 17-18, students sit various school-leaving and university entrance exams. University education scholarships are awarded according to grades achieved in those exams.

Every field of learning is covered in Ukrainian universities, and every urban center has at least one institution of higher learning. The universities confer a bachelor's degree (four years), specialist's degree (usually five years), and master's degree (five to six years). Bachelor's and master's degrees were introduced relatively recently as they did not exist in the Soviet Union.

The first level of postgraduate education is aspirantura (аспирантура) that usually results in the Kandidat nauk degree, Candidate of Sciences). The seeker should pass three exams (in his/her special field, in a foreign language of his/her choice and in philosophy), publish at least three scientific articles, write a dissertation and defend it. This degree is roughly equivalent to the Ph.D. in the United States.

Two to four years of study in doctorantura, publishing research and writinga new thesis would result in the Doctor Nauk degree (Doctor of Sciences), but the typical way is to work in a university or scientific institute while preparing a thesis. The average time between obtaining kandidat and doctor degrees is roughly 10 years, and most new Doctors are 40 and more years old. Only one of four Kandidats reaches this grade.

The major universities are: the National Technical University of Ukraine, the National Taras Shevchenko University of Kiev, the Kharkiv Polytechnical Institute, Lviv University, Lviv Polytechnic, and Kharkiv University.

Class

Under the Soviet regime, the Communist Party elite enjoyed a preferential status in the officially classless society comprising workers, peasants, and working intelligentsia. After independence, numerous former Soviet bureaucrats either retained their status with the new administration, or became rich business professionals. Government-paid education, health care, and research professionals are in the lowest income bracket, and unemployment among blue-collar workers increased as heavy industry adjusted to new requirements. Anyone with cash can buy status symbols such as cars, houses, luxury items, and fashionable clothes

Culture

The culture of Ukraine is a result of influence over millennia from the West and East, with an assortment of strong culturally-identified ethnic groups. Like most Western countries, Ukrainian customs are heavily influenced by Christianity. Russian and other Eastern European cultures also have had a significant impact on the Ukrainian culture.

Architecture

Ukraine has remnants of 6000-year-old two-room dwellings enclosed by walls and moats, as well as sophisticated architecture of the Greek and Roman colonies in the Black Sea region from 500 B.C.E.–100 C.E. that influenced Scythian house building. Slavic tribes built log houses in forested highlands and frame houses in the forest-steppe. Kievan Rus urban centers were built in a European-style, with a prince's fortified palace surrounded by town dwellers’ houses.

Stone was used in public buildings from the tenth century, and Byzantine church architecture combined with local features, as in the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev (about 1030s) and the Holy Trinity Church over the Gate of the Pechersk Monastery (1106–1108). Romanesque half-columns and arches appear in Kievan Rus church architecture from the twelfth century, the Renaissance style appears in the Khotyn and Kamyanets'-Podil'skyi castles, built in the fourteenth century. An example of baroque wooden architecture, with richer ornamentation, is the eighteenth century Trinity Cathedral in former Samara, built for Zaporozhian Cossacks.

Seventeenth and eighteenth century villages used wood and wattled clay and were centered around a church, community buildings, and marketplace, with streets following property lines and land contours. The empire architectural style came from the West, in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with grid-pattern squares and promenades.

The Soviet period brought large plain government buildings and apartment blocks as seen throughout Soviet territories. But Ukrainians prefer single houses with a private space between the street and the house, usually with a garden. People living in apartment buildings partition long hallways into smaller private spaces. Dachas (summer cottage) cooperatives provide summer holiday homes for city dwellers.

Art

The pre-Christian tradition of painted Easter eggs began in Ukraine. A design is created with wax, the egg is dyed, and the wax removed. Kievan Rus art began with icons on wooden panels. Monumental mosaics embellished churches, along with frescoes on the interior walls and staircases. Kiev became a center of engraving in the seventeenth century. The Baroque era secularized Ukrainian painting, popularizing portraiture.

Mykola Pymonenko (1862–1912) organized a painting school in Kiev favoring a post-[[Romantictyle. Nationalism pervaded paintings of Serhii Vasylkyvs'kyi (1854–1917), while Impressionism characterized work by Vasyl (1872–1935) and Fedir Krychevs'ky (1879–1947).

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviets began enforcing socialist realism, which required that all artists and writers glorify the Soviet regime. The muralist Alla Hors'ka, who rejected social realism, was assassinated, and the painter Opanas Zalyvakha was imprisoned in the Gulag.

After World War II, numerous Ukrainian artists emigrated into the United States and other Western countries. Jacques Hnizdovsky (1915–1985) achieved recognition in engraving and woodcuts, Mykhailo Chereshniovsky for stylized sculpture, as did caricaturist Edvard Kozak (1902–1998).

Cuisine

Ukrainians like fish, cheeses and a variety of sausages. Typically bread is a core part of every meal, and must be included for the meal to be "complete." At Christmas time, for example, it is tradition to have a 12-dish Christmas Eve supper. At Christmas time, for example, kutia - a mixture of cooked buckwheat groats, poppy seeds, and honey, and special sweet breads - is prepared. Included at Easter are the famous Pysanky (coloured and patterned eggs). Making these eggs is a long but fun process, and they are not actually eaten, but displayed in the centre of the table (usually around the bread).

Best-known foods are: Salo (salted pork fat with garlic), borshch (a vegetable based soup, usually with beets and beef or pork), holobtsi (cabbage rolls stuffed with rice and meat), varenyky (stuffed dumplings), and pyrohy (a fried, dessert version of varenyky, filled with fruit instead of meat or cheese)

Ukrainians always toast to good health, linger over their meal, and engage in lively conversation with family and friends. Often they will drink tea (chai), wine, or coffee afterwards with a simple dessert, such as a fruit pastry.

Customs

Ukrainians carry themselves in a very polite, civilized manner. Men often hold the door open for a woman when she enters a building, stand up when a woman enters the room, and, if there is a shortage of seats, men will give up their seats to the women. In rural areas, men will sometimes kiss a woman's hand, but this is starting to go out of fashion.

According to convention, when standing at a threshold (doorsill), do not shake hands or offer anything to be taken by the person on the other side. A young unmarried man or woman should not be seated at a table's corner. Always buy an odd number of flowers as a gift, unless it is a funeral. In that case, it is appropriate to buy an even number. When passing through the aisles in a theater or elsewhere, it is polite to face the people sitting down. Do not hesitate to say: please (bud’ laska), thank you (dyakuyu), and you're welcome (proshu).

Dance

A Ukrainian style of dancing is called Kalyna. Both men and women participate. Kalyna dancing involves partner dancing. One dance, called the previtanya, is a greeting dance. It is slow and respectful, the women bow to the audience and present bread with salt on a cloth and flowers. Another, called the hopak is much more lively, and involves many fast-paced movements. Hence hopak as a dance is derived from hopak martial art of Cossacks.

- The women wear colourful costumes, sometimes featuring a solid-coloured (usually blue, green, red, or black) tunic and matching apron, and under that an open skirt, and below that a white skirt with an embroidered hem that should reach an inch or so below the knee. If they wear a tunic, then under that they wear a long-sleeved richly embroidered white shirt. Traditionally, women wear a type of red leather boots to dance in. They also wear a beautiful flower head piece, that is a headband covered with flowers and has long flowing ribbons down the back that flow when they dance, and plain red coral necklaces.

- The men wear baggy pants (usually blue, white, black or red) and a shirt (usually white, but sometimes black) embroidered at the neck and down the stomach. Over the shirt they sometimes will wear a richly embroidered vest. Around their waist they wear a thick sash with fringed ends. Like the women, they wear boots, but these can be black or white in addition to red.

Other traditional dances include: the Kozak, Kozachok, Tropak, Hrechanyky, Kolomiyka and Hutsulka, Metelytsia, Shumka, Arkan, Kateryna (La Mantovana) and Chabarashka. Dances originating outside the Ukrainian ethnic region but which are also popular include: the Polka, Mazurka, Krakowiak, Csárdás, Waltz, Kamarynska and Barynya. Ukrainian instrumental and dance music has influenced Jewish and Gypsy music.

Literature

Ukrainian literature began with Kievan Rus chronicles. The original literature in was written in the Church Slavonic. One major work was the Tale of Bygone Years by Nestor the Chronicler. Another key work was the twelfth century epic (The tale of Igor's campaign). Printing presses were established in Lviv and Ostrih in 1573, where the Ostrih Bible was published in 1581. The sixteenth century included the folk epics called dumy, which celebrated the activities of the Cossacks.

The father of Ukrainian literature in the modern vernacular form of the Ukrainian language is Ivan Kotlyarevsky, who wrote a travesty of Virgil's Aeneid ([1798). This mock epic poem turns Virgil's characters into Ukrainian Cossacks. Its language was based on the spoken Ukrainian of the Poltava region.

In 1837, three writers — Markiian Shashkevych (1811–1843), Ivan Vahylevych (1811–1866) and Yakiv Holovats'kyi (1814–1888)—published a literary collection under the title The Nymph of Dnister, which focused on folklore and history and began to unify the Ukrainian literary language. The 1840 collection of poems entitled Kobzar , by Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861), became symbols of Ukrainian national identity. In the late nineteenth century, Ukrainian writers—Panteleimon Kulish (1819–1897), Marko Vovchok (1834–1907), Ivan Nechuj-Levyts'kyj (1838–1918), Panas Myrnyj (1849–1920), and Borys Hrinchenko (1863–1910)—developed realistic novels and short stories.

After the Soviet takeover, numerous Ukrainian writers emigrated. A group known as the Free Academy of Proletarian Literature (1925–1928) included the poets Pavlo Tychyna (1891–1967) and Mike Johansen (1895–1937), the novelists Yurij Yanovs'kyi (1902–1954) and Valerian Pidmohyl'nyi (1901–1937?), and the dramatist Mykola Kulish (1892–1937). The leader of this group, Mykola Khvyliovyi (1893–1933), advocated an orientation towards Europe and away from Moscow, and the group championed national interests within a Communist ideology. Khvyliovyi killed himself after witnessing the 1933 famine, and most members were arrested and killed in Stalin's prisons.

Socialist realism, from the 1930s to the 1960s, required writers to champion government policies, leading to a new generation of writers, from 1960 to 1970, who rebelled. These included novelist Oles' Honchar (1918–1995), as well as poets Lina Kostenko (1930–), Vasyl' Stus (1938–1985),and Ihor Kalynets' (1938–).

Music

Each ethnic group in Ukraine has its own unique musical traditions. Ukrainian folk songs are based on minor modes or keys. There is solo singing, including holosinnya sung at wakes. There are professional itinerant singers known as kobzari or lirnyky. Lyric historical folk epics known as dumy are sung to the accompaniment of the bandura, kobza or lira. There is an archaic type of modal "a cappella" vocal style in which a phrase sung by a soloist is answered by a choral phrase in two- or three- voice harmony.

Common traditional instruments include: the kobza (lute), bandura, torban (bass lute), violin, basolya (3-string cello), the relya or lyra (hurdy-gurdy) and the tsymbaly; the sopilka (duct flute), floyara (open, end-blown flute), trembita (alpenhorn), fife, koza (bagpipes); and the buben (frame drum), tulumbas (kettledrum), resheto (tambourine) and drymba/varghan (Jaw harp). Traditional instrumental ensembles are often known as troïstï muzyki (from the ‘three musicians’ that typically make up the ensemble, e.g. violin, sopilka and buben). When performing dance melodies instrumental performance usually includes improvisation.

Ukraine has produced classical composer Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart, performers Vladimir Horowitz, David Oistrakh, Sviatoslav Richter. Ukraine and its diaspora have also produced a great number of fine avant-garde composers Baley, Silvestrov, Hrabovsky. There are also musicians (Kostyantyn Chechenya, Wolodymyr Smishkewych, Vadym Borysenko and Roman Turovsky and who have been preserving Ukrainian music of the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Eras.

The 1970s saw the emergence of a number of folk rock groups. One of the most prominent was a group known as Kobza which included two electric banduras. Major contributions were made by songwriter Volodymyr Ivasyuk and singers Sofia Rotaru and Nazariy Yaremchuk.

The 1990s saw an explosion of Ukrainian Pop music, sparked by the Chervona Ruta Festival which was held in Chernivtsi in 1989. Groups that came to prominence were Komu Vnyz, Ne zhurys',

Folkloric elements have made a resurgence in modern Ukrainian pop music. Hutsul folk melodies, rhythms and dance moves were effectively used by the Ukrainian winner of the Eurovision Song Contest 2004 Ruslana. One of the most important and original musicians to come out of Ukraine in recent years is the ultra-avantgarde folk singer and harmonium player Mariana Sadovska.

Ukrainian rock bands include Braty Hadiukiny, Komu Vnyz, Plach Yeremiyi, Taras Petrynenko, Viy, Ivo Bobul, Vopli Vidoplyasova and others. Opalnyi Prynz was, perhaps, the most influential Rock band in the late 80s and early 90s. Okean Elzy, featuring Slava Vakarchuk has long been among the most popular bands of Ukrainian pop-rock, and has had some success abroad.

A prominent hip hop group is Tanok Na Maydani Kongo ("The Dance on the Congo Square") which raps in the Ukrainian language (specifically the Slobozhanshchyna dialect) and mix hip hop with indigenous Ukrainian elements. Most Hip-hop in Ukraine is however in Russian.

Theater and cinema

Ukrainian theater developed from folk shows, known as vertep. Sentimentalist plays were presented during the eighteenth-century. A permanent Ukrainian theater was established in 1864 by the Ruthenian Club in Lviv. Marko Kropyvnyts'kyi (1840–1910), Mykhailo Staryts'kyi (1840–1904), Ivan Karpenko-Karyi (1845–1907), the actors and directors Panas Saksahans'kyi (1859–1940), and Mykola Sadovs'kyi (1856–1933), created historical and social plays. Sadovs'kyi's productions were filmed, marking the beginning of Ukrainian cinema in 1910.

From 1917 to 1922 numerous theaters appeared in Ukraine, the most prominent new figure being Les' Kurbas, the director of The Young Theatre in Kiev. The expressionist style was adopted by film director Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1894–1956), whose first notable movie was the 1926 silent movie “Love's Berries, Dramatist Mykola Kulish (1892–1937) dealt with social and national conflicts in Soviet Ukraine. In 1933–1934 Kurbas, Kulish, and numerous actors were arrested and later killed in Stalin's prisons. Socialist realism became the approved drama style, and party hack Oleksander Korniichuk the main dramatist.

After World War II, Ukrainian actors in refugee camps in Western Europe used theater to preserve national culture. Volodymyr Blavats'kyi (1900–1953) and former Josyp Hirniak continued to perform in professional companies in New York in the 1950s and 1960s.

In cinema of the 1960s, director Kira Muratova utilised existentialist concepts. The impressionistic Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) by Sergij Paradzhanov and Jurii Ilienko won a prize at Cannes. One of the largest film production studios in Ukraine is the Olexandr Dovzhenko Film Studios, located in Kiev. One major Ukrainian distributor is Cinergia, the local distributor of films by Warner Bros., New Line Cinema and Miramax Films.

Sports

When it comes to sports, Ukraine is a typical European country. Of the many different sports Ukraine plays, the major sport is football (soccer). Ukraine has five levels of football. The strongest and most popular league is the Ukrainian Premier League, followed by the Ukrainian First League, the Druha Liha A, Druha Liha B, and Druha Liha C. Clubs are promoted or demoted between leagues according to points scored — three for a win, one point for a draw, and zero points for a loss. Each Ukrainian team plays each other twice. The teams from all leagues can participate in the Ukrainian Cup. The winners of the Ukrainian Championship and the Ukrainian Cup take part in the Ukrainian Super Cup. Ukraine won a joint bid with Poland to host the 2012 UEFA European Football Championship which is the third largest sporting event in the world after the Olympics and the World Cup.

Ukraine has an ice hockey league, and a national ice hockey team. The nation also has a relatively unknown basketball league, although the teams are strong enough to make it into the Eurocup basketball championship. There are numerous cricket clubs. Ukraine is a regular participant in the Olympic Games, both summer and winter.

International rankings

| Organization | Survey | Ranking |

|---|---|---|