Difference between revisions of "Trinity" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (removing unneeded links) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (100 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}} |

| − | {{ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Shield-Trinity-Scutum-Fidei-English.png|frame|right|The "Shield of the Trinity" or "Scutum Fidei" diagram of traditional Western Christian symbolism]] | |

| − | + | The '''Trinity''' in [[Christianity]] is a [[theology|theological]] doctrine developed to explain the relationship of the Father, Son, and [[Holy Spirit]] described in the [[Bible]]. The particular question the doctrine addresses is: If the Father is [[God]], the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, then how can we say that there is only one God and not three Gods? The doctrine, following [[Tertullian]] and the subsequent approval of his formulation by the [[Church]], affirms that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not identical with one another nor separate from one another but simply three distinct persons (''personae'') of one [[substance]] (''una substantia''). It may be rather difficult to comprehend it by reason, but it has since been regarded as a central doctrine and litmus test of the Christian faith. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | After many debates amongst Christian leaders, the consubstantiality between the Father and Son was officially confirmed at the [[Council of Nicea]] in 325, while the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son was officially established at the [[Council of Constantinople]] in 381. Various other explanations of the accepted doctrine of the Trinity were developed. One example is the "mutual indwelling" (''perichoresis'' in [[Greek language|Greek]] and ''circumincessio'' or ''circuminsessio'' in [[Latin language|Latin]]) of the three distinct persons, suggested by theologians such as the [[Cappadocian Fathers]] and [[Augustine of Hippo|Augustine]]. Another one, suggested by Augustine and others in the [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholic]] tradition, is that the three distinct persons are all involved in each of their operations: [[creation]], [[redemption]], and [[sanctification]]. | |

| − | + | In the development of trinitarian doctrine, there have historically emerged positively profound insights such as the distinction between the [[ontology|ontological]] and economic Trinity and the doctrine of vestiges of the Trinity in creation. These insights have led to further creative explorations about the nature of God and God's activity in the world. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The hard fact, however, is that trinitarian orthodoxy is still beset with unsolved difficult issues and criticisms. One internal issue within Christendom is the [[Great Schism]] between East and West over how the Holy Spirit proceeds within the Godhead. There are other issues, such as [[logic|logical]] incoherence in the Trinity and gender issue regarding the members of the Trinity. Meanwhile, nontrinitarians have constantly presented challenging criticisms. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | If these challenging issues and criticisms are to be satisfactorily addressed to present the trinitarian tradition in a more acceptable way, we might have to review the history of the doctrine to find out why these issues and criticisms had to emerge. One particular historical moment worth looking at for this purpose would be when Tertullian rejected both heretical schools of Monarchianism (which were both nontrinitarian) and devised a middle position which, in spite of its rather incomprehensible nature, became trinitarian orthodoxy. Finding a more inclusive, alternative way of dealing with both schools of Monarchianism could lead to better address these issues and criticisms. | |

| − | + | As Christianity is such a dominant force in the religious world (including through the vehicle of European and American power), virtually all religions and cultures have been pressed to have some view of this otherwise internal, theological debate. For example, [[Islam]] accuses Christian trinitarianism of being tritheism. [[Hinduism]] finds threefold concepts resembling the Trinity. | |

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| − | + | The [[Greek language|Greek]] term used for the [[Christianity|Christian]] Trinity, "Τριάς," means "a set of three" or "the number three," from which the [[English language|English]] word ''triad'' is derived. The first recorded use of this Greek term in Christian [[theology]] was in about 180 C.E. by Theophilus of Antioch, who used it of "God, his Word, and his Wisdom." The word "Trinity," however, actually came from the Latin ''Trinitas'', meaning "three-ness," "the property of occurring three at once," or "three are one." In about 200 C.E., [[Tertullian]] used it to describe how the three distinct persons (''personae'') of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are of one [[substance]] (''una substantia''). | |

| − | + | ==Trinity in Scripture== | |

| − | + | [[Image:France Paris St-Denis Trinity-CROPPED.jpg|thumb|right|210px|Depiction of Trinity from Saint Denis Basilica in [[Paris]]]] | |

| − | + | Some passages from the [[Hebrew Bible]] have been cited as supporting the Trinity. It calls God "Elohim," which is a plural noun in Hebrew (Deuteronomy 6:4) and occasionally employs plural pronouns to refer to [[God]]: "Let us make man in our image" (Genesis 1:26). It uses threefold liturgical formulas (Numbers 6:24-26; Isaiah 6:3). Also, it refers to God, his Word, and his Spirit together as co-workers (Psalms 33:6; etc.). However, modern biblical scholars agree that "it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions with later trinitarian doctrine."<ref>Mircea Eliade, ed., "Trinity" in ''The Encyclopedia of Religion'', vol. 15 (New York: MacMillan, 1987), 53.</ref> | |

| − | + | How about the [[New Testament]]? It does not use the word "Τριάς" (Trinity), nor does it explicitly teach it. "Father" is not even a title for the first person of the Trinity but a synonym for God. But, the basis of the Trinity seems to have been established in it. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are associated in the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19). It reflects the [[baptism|baptismal]] practice at Matthew's time or later if this line is interpolated. Although Matthew mentions about a special connection between God the Father and Jesus the Son (e.g., 11:27), he seems not be of the opinion that Jesus is equal with God (cf. 24:36). | |

| + | The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit can be seen together also in the apostolic benediction: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" (2 Corinthians 13:14). It is perhaps the earliest evidence for a tripartite formula, although it is possible that it was later added to the text as it was copied. There is support for the authenticity of the passage since its phrasing "is much closer to Paul's understandings of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit than to a more fully developed concept of the Trinity. Jesus, referred to not as Son but as Lord and [[Christ]], is mentioned first and is connected with the central Pauline theme of grace. God is referred to as a source of love, not as father, and the Spirit promotes sharing within community."<ref>Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan, eds., ''The Oxford Companion to the Bible'' (Oxford University Press, 1993).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The Gospel of John does suggest the equality and unity of Father and Son in passages such as: "I and the Father are one" (10.30). It starts with the affirmation that "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (1.1) and ends (Chap. 21 is more likely a later addition) with Thomas's confession of faith to Jesus, "My Lord and my God!" (20:28). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | These verses caused questions of relation between Father, Son and the Holy Spirit, and have been hotly debated over the centuries. Mainstream Christianity attempted to resolve the issue through writing the creeds. | |

| − | + | There is evidence indicating that one medieval Latin writer, while purporting to quote from the First Epistle of John, inserted a passage now known as the ''Comma Johanneum'' (1 John 5:7) which has often been cited as an explicit reference to the Trinity because it says that the Father, the Word, and Holy Ghost are one. Some Christians are resistant to the elimination of the ''Comma'' from modern Biblical translations. Nonetheless, nearly all recent translations have removed this clause, as it does not appear in older copies of the Epistle and it is not present in the passage as quoted by any of the early Church Fathers, who would have had plenty of reason to quote it in their trinitarian debates (for example, with the Arians), had it existed then. | |

| − | + | Summarizing the role of Scripture in the formation of trinitarian belief, [[Gregory Nazianzus]] (329-389) argues in his ''Orations'' that the revelation was intentionally gradual: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The Old Testament proclaimed the Father openly, and the Son more obscurely. The New manifested the Son, and suggested the deity of the Spirit. Now the Spirit himself dwells among us, and supplies us with a clearer demonstration of himself. For it was not safe, when the Godhead of the Father was not yet acknowledged, plainly to proclaim the Son; nor when that of the Son was not yet received to burden us further<ref>Gregory Nazianzus, ''Orations,'' 31.26.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | == | + | ==Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity== |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Formative period=== | |

| + | The triadic formula for [[baptism]] in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19) can also be found in the [[Didache]], [[Ignatius of Antioch|Ignatius]] (c.35-c.107), [[Tertullian]] (c.160-c.225), [[Hippolytus (writer)|Hippolytus]] (c.170-c.236), [[Cyprian]] (d.258), and [[Gregory Thaumaturgus]] (c.213-c.270). It apparently became a fixed expression soon. | ||

| − | + | But, for the [[monotheism|monotheistic]] [[religion]] of [[Christianity]], the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not three Gods, and only one [[God]] exists. In order to safeguard monotheism, the unity of the Godhead, and God's sole rule or monarchy (''monarchia'' in Greek), therefore, a theological movement called "Monarchianism" emerged in the second century, although unfortunately it ended up being heretical. It had two different schools: Modalistic Monarchianism and Dynamistic Monarchianism. The former safeguarded the unity of the Godhead by saying that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three different successive modes of one and the same God.<ref>Another way of describing the tenet of Modalistic Monarchianism is this: The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are titles which describe how humanity has interacted with or had experiences with God. In the role of the Father, God is the provider and creator of all. In the mode of the Son, we experience God in the flesh, as a human, fully man and fully God. God manifests as the Holy Spirit by actions on earth and within the lives of Christians. This view is known as [[Sabellianism]], and was rejected as heresy by the Ecumenical Councils, although it is still prevalent today among denominations known as "Oneness" and "Apostolic" Pentecostal Christians, the largest of these groups being the United Pentecostal Church.</ref> According to this, the three as modes of God are all one and the same and equally divine. The latter school, on the other hand, defended the unity of the Godhead by saying that the Father alone is God, and that the Son and Holy Spirit are merely creatures. The Son as a created man received a power (''dynamis'' in Greek) from the Father at the time of his baptism to be adopted as the Son of God. In the eyes of many in the Church, both Monarchian schools were two extreme positions, and neither of them was acceptable. | |

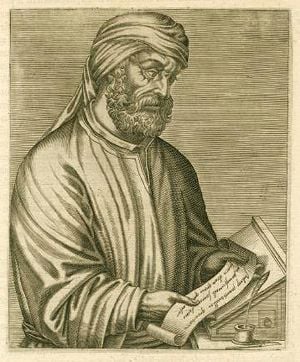

| − | + | [[Image:Tertullian.JPG|thumb|left|Tertullian of Carthage]] | |

| + | [[Tertullian]], therefore, came up with a middle position between the two, by maintaining that the Father, Son, and Holy spirit are neither one and the same, as Modalistic Monarchianism maintained, nor separate, as Dynamistic Monarchianism argued, but rather merely "distinct" from one another. To argue for the distinction (''distinctio'' in Latin) of the three, which is neither their sameness nor their separation (''separatio'' in Latin), Tertullian started to use the expression of "three persons" (''tres personae'' in Latin). The Latin word ''persona'' in the days of Tertullian never meant a self-conscious individual person, which is what is usually meant by the modern English word "person." In those days, it only meant legal ownership or a mask used at the theater. Thus three distinct persons are still of one [[substance]] (''una substantia'' in Latin). It was in this context that Tertullian also used the word ''trinitas.'' Although this trinitarian position was presented by him after he joined a heretical group called the [[Montanism|Montanists]], it was appreciated by the [[Church]] and became an important basis for trinitarian orthodoxy. | ||

| − | The | + | The terms Tertullian coined, ''una substantia'' and ''tres personae,'' considerably influenced the Councils of [[Council of Nicea|Nicea]] (325) and of [[Constantinople]] (381). Nicea affirmed the consubstantiality (''homoousion'' in Greek) of the Son with the Father against the heresy of [[Arianism]], while Constantinople established the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son against the heresy of [[Semi-Arianism]]. For this purpose, Nicea also stated that the Son was not created but begotten of the Father, while Constantinople mentioned that the Holy Spirit was not created but proceeded from the Father. The Nicene use of ''homoousios'' (ὁμοούσιος), meaning "of the same substance," became the hallmark of orthodoxy. This word differed from that used by Arians, ''homoiousios'' ("of ''similar'' substance"), by a single Greek letter, "one iota"—a fact proverbially used to speak of deep divisions, especially in theology, expressed by seemingly small verbal differences. Athanasius (293-373) was the theological pillar for Nicea, while [[Basil the Great]] (c.330-379), [[Gregory of Nazianzus]] (329-389), and [[Gregory of Nyssa]] (c.330-c.395), who are together called [[Cappadocian Fathers]], were instrumental for the decision of Constantinople. [[Athanasius]] and the Cappadocian Fathers also helped to make a distinction between the two Greek words of ''ousia'' and ''hypostasis,'' having them mean Tertullian's ''substantia'' and ''persona,'' respectively. |

| − | === | + | ===Further explanations=== |

| − | A | + | A further explanation of the relationship of the three distinct divine persons of one and the same God was proposed by Athanasius, the Cappadocian Fathers, [[Hilary of Poitiers]], and [[Augustine of Hippo|Augustine]], and it was described as the mutual indwelling or interpenetration of the three, according to which one dwells as inevitably in the others as they do in the one. The mutual indwelling was called ''perichoresis'' in Greek and ''circumincessio'' (or ''circuminsessio'') in Latin. This concept referred for its basis to John 14:11-17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. At that time, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to this theory, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes."<ref>Hilary of Poitiers, [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf209.ii.v.ii.iii.html ''Concerning the Trinity'' 3:1.] Retrieved August 10, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | As still another explanation of the relationship of the three persons, Medieval theologians after Augustine suggested that the external operations of [[creation]], [[redemption]], and [[sanctification]] attributed primarily to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, respectively, should be indivisible (''opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt''). All the three persons are therefore involved in each of those operations. | |

| − | + | While in the East Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers were main contributors for the formation of the doctrine of the Trinity, in the West Augustine besides Tertullian and Hilary of Poitiers was at the forefront for the development of the doctrine. The imprint of the speculative contribution of Augustine can be found, for example, in the Athanasian Creed, composed in the West in the fifth century and therefore not attributed to Athanasius. According to this Creed, each of the three divine persons is eternal, each almighty, none greater or less than another, each God, and yet together being but one God. | |

| − | + | ===Differences between East and West=== | |

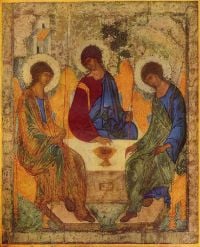

| − | + | [[Image:Andrej Rublëv 001.jpg|thumb|200px|''The Hospitality of [[Abraham]]'' by Andrei Rublev. The three angels symbolize the trinity.]] | |

| − | + | Although the basic position of trinitarian orthodoxy was established by the end of the fourth century, explanations of the doctrine of the Trinity were continuously given as the doctrine spread westward. Differences between East and West in their explanations emerged, therefore. | |

| − | + | The tradition in the West was more prone to make positive statements concerning the relationship of persons in the Trinity. Thus, the Augustinian West was inclined to think in philosophical terms concerning the rationality of God's being, and was prone on this basis to be more open than the East to seek philosophical formulations which make the doctrine more intelligible. | |

| − | + | The Christian East, for its part, correlated ecclesiology and trinitarian doctrine, and sought to understand the doctrine of the Trinity via the experience of the [[Church]], which it understood to be "an icon of the Trinity." So, when Saint Paul wrote concerning Christians that all are "members one of another," Eastern Christians understood this as also applying to the divine persons. | |

| − | + | For example, one Western explanation is based on deductive assumptions of logical necessity, which holds that God is necessarily a Trinity. On this view, the Son is the Father's perfect conception of his own self. Since existence is among the Father's perfections, his self-conception must also exist. Since the Father is one, there can be but one perfect self-conception: the Son. Thus the Son is begotten, or generated, by the Father in an act of ''intellectual'' generation. By contrast, the [[Holy Spirit]] proceeds from the perfect love that exists between the Father and the Son, and as in the case of the Son, this love must share the perfection of person. The Holy Spirit is said to proceed from both the Father "and the Son (''filioque'' in Latin)." The ''filioque'' clause was inserted into the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed in the fifth century by the Roman Church. | |

| − | + | The Eastern Church holds that the ''filioque'' clause constitutes heresy, or at least profound error. One reason for this is that it undermines the personhood of the Holy Spirit; is there not also perfect love between the Father and the Holy Spirit, and if so, would this love not also share the perfection of person? At this rate, there would be an infinite number of persons of the Godhead, unless some persons were subordinate so that their love were less perfect and therefore need not share the perfection of person. The ''filioque'' clause was the main theological reason for the [[Great Schism]] between East and West that took place in 1054. | |

| − | + | [[Anglicanism|Anglicans]] made a commitment at their [[Lambeth Conferences]] of 1978 and 1988 to providing for the use of the Creed without the ''filioque'' clause in future revisions of their liturgies, in deference to the issues of conciliar authority raised by the Orthodox. But, most Protestant groups that use the Creed include the ''filioque'' clause. The issue, however, is usually not controversial among them because their conception is often less exact than is discussed above (exceptions being the Presbyterian [[Westminster Confession]] 2:3, the [[Baptist Confession of Faith|London Baptist Confession]] 2:3, and the Lutheran [[Augsburg Confession]] 1:1-6, which specifically address those issues). The clause is often understood by Protestants to mean that the Spirit is sent from the Father, by the Son — a conception which is not controversial in either Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. A representative view of Protestant trinitarian theology is more difficult to provide, given the diverse and decentralized nature of the various Protestant churches. | |

| − | + | Today, ecumenical dialogue between [[Eastern Orthodoxy]], Roman [[Catholicism]], and trinitarian [[Protestantism]], even involving [[Oriental Orthodoxy]] and the [[Assyrian Church of the East]], seeks an expression of trinitarian as well as Christological doctrine which will overcome the extremely subtle differences that have largely contributed to dividing them into separate communities. The doctrine of the trinity is therefore symbolic, somewhat paradoxically, of both division and unity. | |

| − | + | ==Trinitarian Parallel between God and Creation== | |

| − | + | ===Ontological and economic Trinity=== | |

| − | + | In the [[Christianity|Christian]] tradition, there are two kinds of the Trinity: the [[ontology|ontological]] (or essential or immanent) Trinity and the economic Trinity. The ontological Trinity refers to the reciprocal relationships of the Father, Son, and [[Holy Spirit]] immanent within the essence of God, i.e., the interior life of the Trinity "within itself" (John 1:1-2). The economic Trinity, by contrast, refers to God's relationship with creation, i.e., the acts of the triune [[God]] with respect to the creation, [[history]], [[salvation]], the formation of the [[Church]], the daily lives of believers, etc., describing how the Trinity operates within history in terms of the roles or functions performed by each of the persons of the Trinity. More simply, the ontological Trinity explains who God is, and the economic Trinity what God does. Most Christians believe the economic reflects and reveals the ontological. [[Catholicism|Catholic]] theologian [[Karl Rahner]] goes so far as to say: "''The 'economic' Trinity is the 'immanent' Trinity and the 'immanent' Trinity is the 'economic' Trinity''."<Ref>Karl Rahner. ''The Trinity.'' (Herder & Herder, 1970), 22. Italics his.</ref> | |

| − | + | Trinitarian orthodoxy tries to affirm the equality of the three persons both ontologically and economically. According to it, there is no ontological or economic subordination amongst the three persons. Of course, the Trinity is not symmetrical with regards to origin, for the Son is begotten of the Father (John 3:16), and the Spirit proceeds from the Father (John 15:26). Nevertheless, while both the Son and Spirit thus derive their existence from the Father, they are mutually indwelling to be equal ontologically. It is also true that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have the asymmetrical operations of [[creation]], [[redemption]], and [[sanctification]], respectively, where redemption and sanctification can be considered to have been assigned by the Father to the Son and Holy Spirit, nevertheless, as was mentioned previously, these external operations are not divisible (''opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt''). All the three persons are equally involved in each of these operations. The three persons are equal economically as well, therefore. Thus, they are perfectly united not only in love, consciousness, and will but also in operation and function. | |

| − | [[ | + | In the twentieth century, trinitarians including [[Karl Barth]], Karl Rahner, and Jürgen Moltmann started to have a deeper appreciation of the economic Trinity than in previous centuries, by making it even more economic, i.e., by exteriorizing it toward the realm of creation more, than before. For Barth and Rahner, the Son of the economic Trinity is no longer identical with God the Son of the ontological Trinity. For Barth, Jesus Christ of the economic Trinity is God's partner as man, thus being different from God himself.<ref>Karl Barth. ''The Humanity of God,'' trans. John Newton Thomas and Thomas Wieser (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1960), 46.</ref> For Rahner, in his economic "self-exteriorizaion" to become the Son of the economic Trinity, God "goes out of himself into that which is other than he."<ref>Karl Rahner. ''Theological Investigations.'' vol. IV, trans. Kevin Smyth (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1966), 239.</ref> For Moltmann, the exteriorization process goes even further because he regards not just the Son but all the three persons of the economic Trinity as "three distinct centers of consciousness and action."<ref>Jürgen Moltmann. ''The Trinity and the Kingdom,'' trans. Margaret Kohl (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981), 146.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Vestiges of the Trinity in creation=== | |

| − | + | In the Catholic tradition there is a doctrine of vestiges of the Trinity in creation (''vestigia trinitatis in creatura'') which started from [[Augustine]]. It tries to find traces of the Trinity within the realm of creation. Although a trace of the Trinity in creation may look similar to the economic Trinity in that both have something to do with the realm of creation, nevertheless they are different because the former simply constitutes an [[analogy]] of the Trinity in creation, while the latter is what the triune God does for creation in his economy. | |

| − | + | According to Augustine, as human beings were created in the image of God, an image of the Trinity should be found in them and especially in the human mind. He points to many vestiges of the Trinity such as: 1) lover, loved, and their [[love]]; 2) being, knowing, and willing; 3) memory, understanding, and will; and 4) object seen, attention of mind, and external vision.<ref>Augustine, ''The Trinity.'' (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2003).</ref> | |

| − | + | In fact, Tertullian already gave similar illustrations of the Trinity from nature in order to argue that the three members of the Trinity are distinct yet inseparable: 1) root, tree, and fruit; 2) fountain, river, and stream; and 3) sun, ray, and apex.<ref>Tertullian, "Against Praxeas," in ''The Ante-Nicene Fathers,'' vol. III, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1973), 602-603.</ref> | |

| − | + | All this has a further implication, which is that our human relationships of love are a reflection of the trinitarian relationships of love within the Godhead. In the words of Georges Florovsky, a Greek Orthodox theologian, "Christian 'togetherness' must not degenerate into impersonalism. The idea of the organism must be supplemented by the idea of a symphony of personalities, in which the mystery of the Holy Trinity is reflected."<ref>Georges Florovsky. ''Bible, Church, Tradition: An Eastern Orthodox View.'' (Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1972), 67.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Issues Related to the Trinity== | |

| − | === | + | ===Logical incoherence=== |

| − | + | The doctrine of the Trinity on the face seems to be [[logic|logically]] incoherent as it seems to imply that identity is not transitive: the Father is identical with [[God]], the Son is identical with God, and the Father is not identical with the Son. Recently, there have been two [[philosophy|philosophical]] attempts to defend the logical coherency of the Trinity, one by Richard Swinburne and the other by Peter Geach. The formulation suggested by the former philosopher is free from logical incoherency, because it says that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit should be thought of as numerically distinct Gods, but it is debatable whether this formulation is consistent with [[history|historical]] orthodoxy. Regarding the formulation suggested by the latter philosopher, not all philosophers would agree with its logical coherency, when it says that a coherent statement of the doctrine is possible on the assumption that identity is 'always relative to a sortal term.'"<ref>Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Online, [http://www.rep.routledge.com/article/K105?ssid=102691941&n=1# "Trinity."] Retrieved June 12, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Again, the logical incoherence of the doctrine of the Trinity means that only one God exists and not three Gods, while the Father, Son, and [[Holy Spirit]] are each God. This incoherence between oneness and threeness emerged historically when Tertullian took an incoherent middle position between the oneness of the Modalistic type and the threeness of the Dynamistic type. Given this origin of the logical incoherence of trinitarianism, one possibly workable solution is to see the Trinity comprehensively and boldly enough to be able to accommodate both Modalistic and Dynamistic Monarchianism instead of just rejecting them. It can basically contain two sets of the Trinity structurally: one set in which the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all divine merely as three attributes or modes of God (like Modalistic Monarchianism); and the other in which only the Father is God and the Son and Holy Spirit are discrete from God himself as creatures (like Dynamistic Monarchianism). The relationship of the two sets is that the latter is the economic manifestation of the former. Although the Son and Holy Spirit in the latter Trinity are not God himself, they as creatures can be God-like. (According to [[Greek Orthodoxy|Greek Orthodox]] theology, even creation can be divine.) This comprehensive solution can coherently retain both the oneness of God and the discreteness of each of the three members of the Trinity at the same time. When looked at from the viewpoint of the received distinction between the ontological and economic Trinity, this solution seems to be feasible, although it makes its latter set of the Trinity far more economic than the received economic Trinity. | |

| − | + | ===Gender issue=== | |

| − | Some [[feminism| | + | Some contemporary theologians including [[feminism|feminists]] refer to the persons of the Holy Trinity with gender-neutral language, such as "Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer (or Sanctifier)." This is a recent formulation, which seeks to redefine the Trinity in terms of three roles in salvation or relationships with us, not eternal identities or relationships with each other. Since, however, each of the three divine persons participates indivisibly in the acts of creation, redemption, and sustaining, traditionalist and other Christians reject this formulation as suggesting a new form of modalism. Some theologians and liturgists prefer the alternate expansive terminology of "Source, and Word, and Holy Spirit." |

| − | + | Responding to feminist concerns, orthodox theology has noted the following: a) that the names "Father" and "Son" are clearly analogical, since all trinitarians would agree that God has no gender ''per se'', encompassing ''all'' sex and gender and being ''beyond'' all sex and gender; b) that using "Son" to refer to the second divine person is most proper only when referring to the "Incarnate Word," who is Jesus, a human who is clearly male; and c) that in Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic, the noun translated "spirit" is grammatically feminine, and also images of God's Spirit in [[Scripture]] are often feminine, as with the Spirit "brooding" over the primordial chaos in Genesis 1, or grammatically feminine, such as a dove in the New Testament. | |

| − | + | The last point on the possible femininity of the Holy Spirit is further explored by saying that if the Son is considered to be masculine as the incarnation of the ''Logos,'' the masculine term for Word in Greek, then the Holy Spirit can be considered to be feminine as something related to the ''Sophia,'' the feminine counterpart that means Wisdom in Greek. | |

| − | + | Historically, [[Coptic Christianity]] saw the Holy Spirit as the Mother, while regarding the two others as the Father and Son. So did [[Zinzendorf]] (1700-1760), the founder of [[Moravianism]]. More recently, Catholic scholars such as Willi Moll and Franz Mayr have decided that the Holy Spirit be feminine on the analogy of family relationships.<ref>Willi Moll, ''The Christian Image of Women'' (Notre Dame: Fides, 1967); Franz Mayr, "Trinitätstheologie und theologische Anthropologie," ''Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche'' 68 (1971):474.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ===Ambivalence to trinitarian doctrine=== |

| − | + | Some Protestant Christians, particularly members of the [[Restoration Movement]], are ambivalent about the doctrine of the trinity. While not specifically rejecting trinitarianism or presenting an alternative doctrine of the Godhead and God's relationship with humanity, they are not dogmatic about the Trinity or do not hold it as a test of true Christian faith. Some, like the [[Society of Friends]] and Christian [[Unitarianism|Unitarians]] may reject all doctrinal or creedal tests of true faith. Some, like the Restorationist [[Churches of Christ]], in keeping with a distinctive understanding of Scripture alone, say that since it is not clearly articulated in the Bible it cannot be required for salvation. Others may look to church tradition and say that there has always been a Christian tradition that faithfully followed Jesus without such a doctrine, since as a doctrine steeped in Greek philosophical distinctions it was not clearly articulated for some centuries after Christ. | |

| − | + | ===Nontrinitarian criticisms=== | |

| − | + | Nontrinitarians commonly make the following claims in opposition to trinitarianism: | |

| − | + | * That it is an invention of early Church Fathers such as Tertullian. | |

| + | * That it is paradoxical and therefore not in line with reason. | ||

| + | * That the doctrine relies almost entirely on non-Biblical terminology. Some notable examples include: trinity, three-in-one, God the Son, God the Holy Ghost, person in relation to anyone other than Jesus Christ being the image of God's person (''hypostasis''). | ||

| + | * That the scriptural support for the doctrine is implicit at best. For example, the New Testament refers to the Father and the Son together much more often than to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and the word "trinity" doesn't appear in the Bible. | ||

| + | * That scripture contradicts the doctrine, such as when Jesus states that the Father is greater than he is, or the Pauline theology: "Yet to us there is one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we unto him; and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and we through him." | ||

| + | * That it does not follow the strict monotheism found in Judaism and the Old Testament, of which Jesus claimed to have fulfilled. | ||

| + | * That it reflects the influence of pagan religions, some of which have divine triads of their own. | ||

| + | * That a triune God is a heavenly substitute for the human family for people, like monks and nuns, that have no earthly family.<ref>Ludwig Feuerbach. ''The Essence of Christianity.'' (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1957), 73.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Since trinitarianism is central to so much of church doctrine, nontrinitarians have mostly been groups that existed before the Nicene Creed was codified in 325 or are groups that developed after the [[Protestant Reformation]], when many church doctrines came into question. | |

| + | |||

| + | In the early centuries of Christian history, [[Arians]], [[Ebionites]], [[Gnostics]], [[Marcionites]], and others held nontrinitarian beliefs. After the Nicene Creed raised the issue of the relationship between Jesus' divine and human natures, [[Monophysitism]] ("one nature") and [[monothelitism]] ("one will") were heretical attempts to explain this relationship. During more than a thousand years of trinitarian orthodoxy, formal nontrinitarianism, i.e., a nontrinitarian doctrine held by a church, group, or movement, was rare, but it did appear, for example, among the [[Cathars]] of the thirteenth century. The Protestant Reformation of the 1500s also brought tradition into question, although at first, nontrinitarians were executed (such as [[Servetus]]), or forced to keep their beliefs secret (such as [[Isaac Newton]]). The eventual establishment of religious freedom, however, allowed nontrinitarians to more easily preach their beliefs, and the nineteenth century saw the establishment of several nontrinitarian groups in North America and elsewhere. These include [[Christadelphians]], [[Christian Scientists]], [[Jehovah's Witnesses]], [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]], and [[Unitarianism|Unitarians]]. Twentieth-century nontrinitarian movements include Iglesia ni Cristo, and Oneness Pentecostals. Nontrinitarian groups differ from one another in their views of Jesus Christ, depicting him variously as a divine being second only to God the Father, Yahweh of the Hebrew Bible in human form, God (but not eternally God), prophet, or simply a holy man. It is interesting to note that nontrinitarians are basically of two types: the type of Modalistic Monarchianism and the type of Dynamistic Monarchianism. | ||

| − | + | ==Non-Christian Views of the Trinity== | |

| − | + | The concept of the Trinity has evoked mixed reactions in other world religions. Followers of Islam have often denounced this Christian doctrine as a corruption of pure [[monotheism]]. They see the doctrine as "evidence" that Christianity has fallen away from the true path of worshiping the one and only God, [[Allah]]. Muslim rejection of the Trinity concept is sometimes associated with the view that Christians are misguided [[polytheism|polytheists]]. However, when the Qur'an speaks of the "trinity," it refers to [[God]], [[Jesus]] and [[Mary (mother of Jesus)|Mary]]—a threesome that is not recognizable as the Christian Trinity. Hence there may be room for dialogue on this issue. | |

| − | + | Other religions have embraced a much more positive attitude towards the Trinity. Correspondences with parallel "threefold" concepts in non-Christian religions have been the foci of much [[inter-religious dialogue]] over the last century. For instance, the concept of [[Trimurti]] (three forms of God) in [[Hinduism]] has been an active topic in much Hindu-Christian dialogue. Additional discussions centering on the Trinity have addressed how the doctrine relates to [[Hinduism|Hindu]] understandings of the supreme [[Brahman]] as "Sat-Cit-Ananda" (absolute truth, consciousness and bliss). | |

| − | + | It has also been noted by scholars that many prototypes, antecedents, and precedents for the Trinity existed in the ancient world (including examples in so-called "pagan" religions), and therefore Christianity was not likely the first religion to cultivate this theological idea. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Assessment== |

| − | + | The doctrine of the Trinity as a central [[Christianity|Christian]] doctrine attempts to disclose a deep truth about the nature of God and the triadic nature of reality. Yet it remains beset by difficulties and criticisms. Hence, it can be expected that theologians will continue to reach for new ways of describing this concept. | |

| − | + | The issue of logical incoherence between oneness and threeness originated with [[Tertullian]]'s third-century formulation, in which he chose a middle position between the oneness of Modalistic Monarchianism and the threeness of Dynamistic Monarchianism, as discussed above. Actually, to this day all nontrinitarian Christians are basically of these two types—either Modalistic Monarchians or Dynamistic Monarchians. | |

| − | + | One proposal to address this issue seeks alternative ways to bridge the divide between both schools of Monarchianism—to affirm simultaneous oneness and threeness without any incoherence. It would structurally involve two different sets of the Trinity: one set affirming the oneness of the triad, the other set recognizing the threeness of the One as expressed in the realm of creation. The latter set would be regarded as the economic manifestation of the former. | |

| − | + | This proposal, by upholding the oneness of the Godhead, the unity of the essential Trinity, would thus seek to answer the charge of tritheism. And by recognizing the three distinct personalities of the economic Trinity as it manifests in the created order as God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit that descended at Pentecost, it does justice to the Christian experience of salvation and sanctification. The feasibility of this proposal can be tested by how relevant it is to the received distinction between the ontological and economic Trinity. | |

| + | |||

| + | The gender issue is a bit more complicated. According to the Bible, however, men and women were created in the image of [[God]], which therefore can be considered to be both male and female. Hence we would affirm that at least one of the members in both sets of the Trinity can be deemed to be female. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | The | + | ==References== |

| + | * Augustine. ''The Trinity.'' Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2003. ISBN 0813213525 | ||

| + | * Barth, Karl. ''The Humanity of God,'' Translated by John Newton Thomas and Thomas Wieser. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1960. ISBN 0804206120 | ||

| + | * Eliade, Mircea (ed.), "Trinity" in ''The Encyclopedia of Religion.'' Vol. 15. New York: MacMillan, 1987. | ||

| + | * Feuerbach, Ludwig. ''The Essence of Christianity.'' New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1957. | ||

| + | * Florovsky, Georges. ''Bible, Church, Tradition: An Eastern Orthodox View.'' Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1972. | ||

| + | * Hilary of Poitiers. [http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf209.ii.v.ii.iii.html ''Concerning the Trinity'']. ''Christian Classics Ethereal Library''. Retrieved August 10, 2007. | ||

| + | * Kittel, Gerhard and Gerhard Friedrich (eds.). ''Theological Dictionary of the New Testament,'' Translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985. ISBN 0802824048 | ||

| + | * LaCugna, Catherine Mowry. ''God For Us: The Trinity and Christian Life.'' HarperSanFrancisco, 1993. ISBN 978-0060649135 | ||

| + | * Mayr, Franz. "Trinitätstheologie und theologische Anthropologie." ''Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche'' 68 (1971). | ||

| + | * Metzger, Bruce M. and Michael David Coogan (eds.). ''The Oxford Companion to the Bible.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780195046458 | ||

| + | * Metzger, Bruce M. and Bart D. Ehrman. ''The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195161229 | ||

| + | * Moll, Willi. ''The Christian Image of Women.'' Notre Dame: Fides, 1967. | ||

| + | * Moltmann, Jürgen. ''The Trinity and the Kingdom,'' Translated by Margaret Kohl. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981. | ||

| + | * Newton, Isaac. ''An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture.'' R. Taylor (Publisher), 1830. | ||

| + | * Rahner, Karl. ''The Trinity.'' Herder & Herder, 1997. ISBN 9780824516277 | ||

| + | * Tertullian. "Against Praxeas". In ''The Ante-Nicene Fathers.'' Vol. III, Edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973. | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| + | All links retrieved May 2, 2023. | ||

| + | *The Catholic Encyclopedia. [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15047a.htm "The Blessed Trinity."] | ||

| + | *Jewish Encyclopedia. [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=338&letter=T "Trinity."] | ||

| − | + | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | |

| + | [[Category: Religion]] | ||

| − | + | {{Credit|Trinity|114218654|Comma_Johanneum|144747869}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 17:40, 2 May 2023

The Trinity in Christianity is a theological doctrine developed to explain the relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit described in the Bible. The particular question the doctrine addresses is: If the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, then how can we say that there is only one God and not three Gods? The doctrine, following Tertullian and the subsequent approval of his formulation by the Church, affirms that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not identical with one another nor separate from one another but simply three distinct persons (personae) of one substance (una substantia). It may be rather difficult to comprehend it by reason, but it has since been regarded as a central doctrine and litmus test of the Christian faith.

After many debates amongst Christian leaders, the consubstantiality between the Father and Son was officially confirmed at the Council of Nicea in 325, while the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son was officially established at the Council of Constantinople in 381. Various other explanations of the accepted doctrine of the Trinity were developed. One example is the "mutual indwelling" (perichoresis in Greek and circumincessio or circuminsessio in Latin) of the three distinct persons, suggested by theologians such as the Cappadocian Fathers and Augustine. Another one, suggested by Augustine and others in the Roman Catholic tradition, is that the three distinct persons are all involved in each of their operations: creation, redemption, and sanctification.

In the development of trinitarian doctrine, there have historically emerged positively profound insights such as the distinction between the ontological and economic Trinity and the doctrine of vestiges of the Trinity in creation. These insights have led to further creative explorations about the nature of God and God's activity in the world.

The hard fact, however, is that trinitarian orthodoxy is still beset with unsolved difficult issues and criticisms. One internal issue within Christendom is the Great Schism between East and West over how the Holy Spirit proceeds within the Godhead. There are other issues, such as logical incoherence in the Trinity and gender issue regarding the members of the Trinity. Meanwhile, nontrinitarians have constantly presented challenging criticisms.

If these challenging issues and criticisms are to be satisfactorily addressed to present the trinitarian tradition in a more acceptable way, we might have to review the history of the doctrine to find out why these issues and criticisms had to emerge. One particular historical moment worth looking at for this purpose would be when Tertullian rejected both heretical schools of Monarchianism (which were both nontrinitarian) and devised a middle position which, in spite of its rather incomprehensible nature, became trinitarian orthodoxy. Finding a more inclusive, alternative way of dealing with both schools of Monarchianism could lead to better address these issues and criticisms.

As Christianity is such a dominant force in the religious world (including through the vehicle of European and American power), virtually all religions and cultures have been pressed to have some view of this otherwise internal, theological debate. For example, Islam accuses Christian trinitarianism of being tritheism. Hinduism finds threefold concepts resembling the Trinity.

Etymology

The Greek term used for the Christian Trinity, "Τριάς," means "a set of three" or "the number three," from which the English word triad is derived. The first recorded use of this Greek term in Christian theology was in about 180 C.E. by Theophilus of Antioch, who used it of "God, his Word, and his Wisdom." The word "Trinity," however, actually came from the Latin Trinitas, meaning "three-ness," "the property of occurring three at once," or "three are one." In about 200 C.E., Tertullian used it to describe how the three distinct persons (personae) of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are of one substance (una substantia).

Trinity in Scripture

Some passages from the Hebrew Bible have been cited as supporting the Trinity. It calls God "Elohim," which is a plural noun in Hebrew (Deuteronomy 6:4) and occasionally employs plural pronouns to refer to God: "Let us make man in our image" (Genesis 1:26). It uses threefold liturgical formulas (Numbers 6:24-26; Isaiah 6:3). Also, it refers to God, his Word, and his Spirit together as co-workers (Psalms 33:6; etc.). However, modern biblical scholars agree that "it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions with later trinitarian doctrine."[1]

How about the New Testament? It does not use the word "Τριάς" (Trinity), nor does it explicitly teach it. "Father" is not even a title for the first person of the Trinity but a synonym for God. But, the basis of the Trinity seems to have been established in it. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are associated in the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19). It reflects the baptismal practice at Matthew's time or later if this line is interpolated. Although Matthew mentions about a special connection between God the Father and Jesus the Son (e.g., 11:27), he seems not be of the opinion that Jesus is equal with God (cf. 24:36).

The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit can be seen together also in the apostolic benediction: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" (2 Corinthians 13:14). It is perhaps the earliest evidence for a tripartite formula, although it is possible that it was later added to the text as it was copied. There is support for the authenticity of the passage since its phrasing "is much closer to Paul's understandings of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit than to a more fully developed concept of the Trinity. Jesus, referred to not as Son but as Lord and Christ, is mentioned first and is connected with the central Pauline theme of grace. God is referred to as a source of love, not as father, and the Spirit promotes sharing within community."[2]

The Gospel of John does suggest the equality and unity of Father and Son in passages such as: "I and the Father are one" (10.30). It starts with the affirmation that "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (1.1) and ends (Chap. 21 is more likely a later addition) with Thomas's confession of faith to Jesus, "My Lord and my God!" (20:28).

These verses caused questions of relation between Father, Son and the Holy Spirit, and have been hotly debated over the centuries. Mainstream Christianity attempted to resolve the issue through writing the creeds.

There is evidence indicating that one medieval Latin writer, while purporting to quote from the First Epistle of John, inserted a passage now known as the Comma Johanneum (1 John 5:7) which has often been cited as an explicit reference to the Trinity because it says that the Father, the Word, and Holy Ghost are one. Some Christians are resistant to the elimination of the Comma from modern Biblical translations. Nonetheless, nearly all recent translations have removed this clause, as it does not appear in older copies of the Epistle and it is not present in the passage as quoted by any of the early Church Fathers, who would have had plenty of reason to quote it in their trinitarian debates (for example, with the Arians), had it existed then.

Summarizing the role of Scripture in the formation of trinitarian belief, Gregory Nazianzus (329-389) argues in his Orations that the revelation was intentionally gradual:

The Old Testament proclaimed the Father openly, and the Son more obscurely. The New manifested the Son, and suggested the deity of the Spirit. Now the Spirit himself dwells among us, and supplies us with a clearer demonstration of himself. For it was not safe, when the Godhead of the Father was not yet acknowledged, plainly to proclaim the Son; nor when that of the Son was not yet received to burden us further[3]

Historical Development of the Doctrine of the Trinity

Formative period

The triadic formula for baptism in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19) can also be found in the Didache, Ignatius (c.35-c.107), Tertullian (c.160-c.225), Hippolytus (c.170-c.236), Cyprian (d.258), and Gregory Thaumaturgus (c.213-c.270). It apparently became a fixed expression soon.

But, for the monotheistic religion of Christianity, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not three Gods, and only one God exists. In order to safeguard monotheism, the unity of the Godhead, and God's sole rule or monarchy (monarchia in Greek), therefore, a theological movement called "Monarchianism" emerged in the second century, although unfortunately it ended up being heretical. It had two different schools: Modalistic Monarchianism and Dynamistic Monarchianism. The former safeguarded the unity of the Godhead by saying that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three different successive modes of one and the same God.[4] According to this, the three as modes of God are all one and the same and equally divine. The latter school, on the other hand, defended the unity of the Godhead by saying that the Father alone is God, and that the Son and Holy Spirit are merely creatures. The Son as a created man received a power (dynamis in Greek) from the Father at the time of his baptism to be adopted as the Son of God. In the eyes of many in the Church, both Monarchian schools were two extreme positions, and neither of them was acceptable.

Tertullian, therefore, came up with a middle position between the two, by maintaining that the Father, Son, and Holy spirit are neither one and the same, as Modalistic Monarchianism maintained, nor separate, as Dynamistic Monarchianism argued, but rather merely "distinct" from one another. To argue for the distinction (distinctio in Latin) of the three, which is neither their sameness nor their separation (separatio in Latin), Tertullian started to use the expression of "three persons" (tres personae in Latin). The Latin word persona in the days of Tertullian never meant a self-conscious individual person, which is what is usually meant by the modern English word "person." In those days, it only meant legal ownership or a mask used at the theater. Thus three distinct persons are still of one substance (una substantia in Latin). It was in this context that Tertullian also used the word trinitas. Although this trinitarian position was presented by him after he joined a heretical group called the Montanists, it was appreciated by the Church and became an important basis for trinitarian orthodoxy.

The terms Tertullian coined, una substantia and tres personae, considerably influenced the Councils of Nicea (325) and of Constantinople (381). Nicea affirmed the consubstantiality (homoousion in Greek) of the Son with the Father against the heresy of Arianism, while Constantinople established the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son against the heresy of Semi-Arianism. For this purpose, Nicea also stated that the Son was not created but begotten of the Father, while Constantinople mentioned that the Holy Spirit was not created but proceeded from the Father. The Nicene use of homoousios (ὁμοούσιος), meaning "of the same substance," became the hallmark of orthodoxy. This word differed from that used by Arians, homoiousios ("of similar substance"), by a single Greek letter, "one iota"—a fact proverbially used to speak of deep divisions, especially in theology, expressed by seemingly small verbal differences. Athanasius (293-373) was the theological pillar for Nicea, while Basil the Great (c.330-379), Gregory of Nazianzus (329-389), and Gregory of Nyssa (c.330-c.395), who are together called Cappadocian Fathers, were instrumental for the decision of Constantinople. Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers also helped to make a distinction between the two Greek words of ousia and hypostasis, having them mean Tertullian's substantia and persona, respectively.

Further explanations

A further explanation of the relationship of the three distinct divine persons of one and the same God was proposed by Athanasius, the Cappadocian Fathers, Hilary of Poitiers, and Augustine, and it was described as the mutual indwelling or interpenetration of the three, according to which one dwells as inevitably in the others as they do in the one. The mutual indwelling was called perichoresis in Greek and circumincessio (or circuminsessio) in Latin. This concept referred for its basis to John 14:11-17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. At that time, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to this theory, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes."[5]

As still another explanation of the relationship of the three persons, Medieval theologians after Augustine suggested that the external operations of creation, redemption, and sanctification attributed primarily to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, respectively, should be indivisible (opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt). All the three persons are therefore involved in each of those operations.

While in the East Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers were main contributors for the formation of the doctrine of the Trinity, in the West Augustine besides Tertullian and Hilary of Poitiers was at the forefront for the development of the doctrine. The imprint of the speculative contribution of Augustine can be found, for example, in the Athanasian Creed, composed in the West in the fifth century and therefore not attributed to Athanasius. According to this Creed, each of the three divine persons is eternal, each almighty, none greater or less than another, each God, and yet together being but one God.

Differences between East and West

Although the basic position of trinitarian orthodoxy was established by the end of the fourth century, explanations of the doctrine of the Trinity were continuously given as the doctrine spread westward. Differences between East and West in their explanations emerged, therefore.

The tradition in the West was more prone to make positive statements concerning the relationship of persons in the Trinity. Thus, the Augustinian West was inclined to think in philosophical terms concerning the rationality of God's being, and was prone on this basis to be more open than the East to seek philosophical formulations which make the doctrine more intelligible.

The Christian East, for its part, correlated ecclesiology and trinitarian doctrine, and sought to understand the doctrine of the Trinity via the experience of the Church, which it understood to be "an icon of the Trinity." So, when Saint Paul wrote concerning Christians that all are "members one of another," Eastern Christians understood this as also applying to the divine persons.

For example, one Western explanation is based on deductive assumptions of logical necessity, which holds that God is necessarily a Trinity. On this view, the Son is the Father's perfect conception of his own self. Since existence is among the Father's perfections, his self-conception must also exist. Since the Father is one, there can be but one perfect self-conception: the Son. Thus the Son is begotten, or generated, by the Father in an act of intellectual generation. By contrast, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the perfect love that exists between the Father and the Son, and as in the case of the Son, this love must share the perfection of person. The Holy Spirit is said to proceed from both the Father "and the Son (filioque in Latin)." The filioque clause was inserted into the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed in the fifth century by the Roman Church.

The Eastern Church holds that the filioque clause constitutes heresy, or at least profound error. One reason for this is that it undermines the personhood of the Holy Spirit; is there not also perfect love between the Father and the Holy Spirit, and if so, would this love not also share the perfection of person? At this rate, there would be an infinite number of persons of the Godhead, unless some persons were subordinate so that their love were less perfect and therefore need not share the perfection of person. The filioque clause was the main theological reason for the Great Schism between East and West that took place in 1054.

Anglicans made a commitment at their Lambeth Conferences of 1978 and 1988 to providing for the use of the Creed without the filioque clause in future revisions of their liturgies, in deference to the issues of conciliar authority raised by the Orthodox. But, most Protestant groups that use the Creed include the filioque clause. The issue, however, is usually not controversial among them because their conception is often less exact than is discussed above (exceptions being the Presbyterian Westminster Confession 2:3, the London Baptist Confession 2:3, and the Lutheran Augsburg Confession 1:1-6, which specifically address those issues). The clause is often understood by Protestants to mean that the Spirit is sent from the Father, by the Son — a conception which is not controversial in either Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. A representative view of Protestant trinitarian theology is more difficult to provide, given the diverse and decentralized nature of the various Protestant churches.

Today, ecumenical dialogue between Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, and trinitarian Protestantism, even involving Oriental Orthodoxy and the Assyrian Church of the East, seeks an expression of trinitarian as well as Christological doctrine which will overcome the extremely subtle differences that have largely contributed to dividing them into separate communities. The doctrine of the trinity is therefore symbolic, somewhat paradoxically, of both division and unity.

Trinitarian Parallel between God and Creation

Ontological and economic Trinity

In the Christian tradition, there are two kinds of the Trinity: the ontological (or essential or immanent) Trinity and the economic Trinity. The ontological Trinity refers to the reciprocal relationships of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit immanent within the essence of God, i.e., the interior life of the Trinity "within itself" (John 1:1-2). The economic Trinity, by contrast, refers to God's relationship with creation, i.e., the acts of the triune God with respect to the creation, history, salvation, the formation of the Church, the daily lives of believers, etc., describing how the Trinity operates within history in terms of the roles or functions performed by each of the persons of the Trinity. More simply, the ontological Trinity explains who God is, and the economic Trinity what God does. Most Christians believe the economic reflects and reveals the ontological. Catholic theologian Karl Rahner goes so far as to say: "The 'economic' Trinity is the 'immanent' Trinity and the 'immanent' Trinity is the 'economic' Trinity."[6]

Trinitarian orthodoxy tries to affirm the equality of the three persons both ontologically and economically. According to it, there is no ontological or economic subordination amongst the three persons. Of course, the Trinity is not symmetrical with regards to origin, for the Son is begotten of the Father (John 3:16), and the Spirit proceeds from the Father (John 15:26). Nevertheless, while both the Son and Spirit thus derive their existence from the Father, they are mutually indwelling to be equal ontologically. It is also true that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have the asymmetrical operations of creation, redemption, and sanctification, respectively, where redemption and sanctification can be considered to have been assigned by the Father to the Son and Holy Spirit, nevertheless, as was mentioned previously, these external operations are not divisible (opera trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt). All the three persons are equally involved in each of these operations. The three persons are equal economically as well, therefore. Thus, they are perfectly united not only in love, consciousness, and will but also in operation and function.

In the twentieth century, trinitarians including Karl Barth, Karl Rahner, and Jürgen Moltmann started to have a deeper appreciation of the economic Trinity than in previous centuries, by making it even more economic, i.e., by exteriorizing it toward the realm of creation more, than before. For Barth and Rahner, the Son of the economic Trinity is no longer identical with God the Son of the ontological Trinity. For Barth, Jesus Christ of the economic Trinity is God's partner as man, thus being different from God himself.[7] For Rahner, in his economic "self-exteriorizaion" to become the Son of the economic Trinity, God "goes out of himself into that which is other than he."[8] For Moltmann, the exteriorization process goes even further because he regards not just the Son but all the three persons of the economic Trinity as "three distinct centers of consciousness and action."[9]

Vestiges of the Trinity in creation

In the Catholic tradition there is a doctrine of vestiges of the Trinity in creation (vestigia trinitatis in creatura) which started from Augustine. It tries to find traces of the Trinity within the realm of creation. Although a trace of the Trinity in creation may look similar to the economic Trinity in that both have something to do with the realm of creation, nevertheless they are different because the former simply constitutes an analogy of the Trinity in creation, while the latter is what the triune God does for creation in his economy.

According to Augustine, as human beings were created in the image of God, an image of the Trinity should be found in them and especially in the human mind. He points to many vestiges of the Trinity such as: 1) lover, loved, and their love; 2) being, knowing, and willing; 3) memory, understanding, and will; and 4) object seen, attention of mind, and external vision.[10]

In fact, Tertullian already gave similar illustrations of the Trinity from nature in order to argue that the three members of the Trinity are distinct yet inseparable: 1) root, tree, and fruit; 2) fountain, river, and stream; and 3) sun, ray, and apex.[11]

All this has a further implication, which is that our human relationships of love are a reflection of the trinitarian relationships of love within the Godhead. In the words of Georges Florovsky, a Greek Orthodox theologian, "Christian 'togetherness' must not degenerate into impersonalism. The idea of the organism must be supplemented by the idea of a symphony of personalities, in which the mystery of the Holy Trinity is reflected."[12]

Issues Related to the Trinity

Logical incoherence

The doctrine of the Trinity on the face seems to be logically incoherent as it seems to imply that identity is not transitive: the Father is identical with God, the Son is identical with God, and the Father is not identical with the Son. Recently, there have been two philosophical attempts to defend the logical coherency of the Trinity, one by Richard Swinburne and the other by Peter Geach. The formulation suggested by the former philosopher is free from logical incoherency, because it says that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit should be thought of as numerically distinct Gods, but it is debatable whether this formulation is consistent with historical orthodoxy. Regarding the formulation suggested by the latter philosopher, not all philosophers would agree with its logical coherency, when it says that a coherent statement of the doctrine is possible on the assumption that identity is 'always relative to a sortal term.'"[13]

Again, the logical incoherence of the doctrine of the Trinity means that only one God exists and not three Gods, while the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each God. This incoherence between oneness and threeness emerged historically when Tertullian took an incoherent middle position between the oneness of the Modalistic type and the threeness of the Dynamistic type. Given this origin of the logical incoherence of trinitarianism, one possibly workable solution is to see the Trinity comprehensively and boldly enough to be able to accommodate both Modalistic and Dynamistic Monarchianism instead of just rejecting them. It can basically contain two sets of the Trinity structurally: one set in which the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all divine merely as three attributes or modes of God (like Modalistic Monarchianism); and the other in which only the Father is God and the Son and Holy Spirit are discrete from God himself as creatures (like Dynamistic Monarchianism). The relationship of the two sets is that the latter is the economic manifestation of the former. Although the Son and Holy Spirit in the latter Trinity are not God himself, they as creatures can be God-like. (According to Greek Orthodox theology, even creation can be divine.) This comprehensive solution can coherently retain both the oneness of God and the discreteness of each of the three members of the Trinity at the same time. When looked at from the viewpoint of the received distinction between the ontological and economic Trinity, this solution seems to be feasible, although it makes its latter set of the Trinity far more economic than the received economic Trinity.

Gender issue

Some contemporary theologians including feminists refer to the persons of the Holy Trinity with gender-neutral language, such as "Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer (or Sanctifier)." This is a recent formulation, which seeks to redefine the Trinity in terms of three roles in salvation or relationships with us, not eternal identities or relationships with each other. Since, however, each of the three divine persons participates indivisibly in the acts of creation, redemption, and sustaining, traditionalist and other Christians reject this formulation as suggesting a new form of modalism. Some theologians and liturgists prefer the alternate expansive terminology of "Source, and Word, and Holy Spirit."

Responding to feminist concerns, orthodox theology has noted the following: a) that the names "Father" and "Son" are clearly analogical, since all trinitarians would agree that God has no gender per se, encompassing all sex and gender and being beyond all sex and gender; b) that using "Son" to refer to the second divine person is most proper only when referring to the "Incarnate Word," who is Jesus, a human who is clearly male; and c) that in Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic, the noun translated "spirit" is grammatically feminine, and also images of God's Spirit in Scripture are often feminine, as with the Spirit "brooding" over the primordial chaos in Genesis 1, or grammatically feminine, such as a dove in the New Testament.

The last point on the possible femininity of the Holy Spirit is further explored by saying that if the Son is considered to be masculine as the incarnation of the Logos, the masculine term for Word in Greek, then the Holy Spirit can be considered to be feminine as something related to the Sophia, the feminine counterpart that means Wisdom in Greek.

Historically, Coptic Christianity saw the Holy Spirit as the Mother, while regarding the two others as the Father and Son. So did Zinzendorf (1700-1760), the founder of Moravianism. More recently, Catholic scholars such as Willi Moll and Franz Mayr have decided that the Holy Spirit be feminine on the analogy of family relationships.[14]

Ambivalence to trinitarian doctrine

Some Protestant Christians, particularly members of the Restoration Movement, are ambivalent about the doctrine of the trinity. While not specifically rejecting trinitarianism or presenting an alternative doctrine of the Godhead and God's relationship with humanity, they are not dogmatic about the Trinity or do not hold it as a test of true Christian faith. Some, like the Society of Friends and Christian Unitarians may reject all doctrinal or creedal tests of true faith. Some, like the Restorationist Churches of Christ, in keeping with a distinctive understanding of Scripture alone, say that since it is not clearly articulated in the Bible it cannot be required for salvation. Others may look to church tradition and say that there has always been a Christian tradition that faithfully followed Jesus without such a doctrine, since as a doctrine steeped in Greek philosophical distinctions it was not clearly articulated for some centuries after Christ.

Nontrinitarian criticisms

Nontrinitarians commonly make the following claims in opposition to trinitarianism:

- That it is an invention of early Church Fathers such as Tertullian.

- That it is paradoxical and therefore not in line with reason.

- That the doctrine relies almost entirely on non-Biblical terminology. Some notable examples include: trinity, three-in-one, God the Son, God the Holy Ghost, person in relation to anyone other than Jesus Christ being the image of God's person (hypostasis).

- That the scriptural support for the doctrine is implicit at best. For example, the New Testament refers to the Father and the Son together much more often than to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and the word "trinity" doesn't appear in the Bible.

- That scripture contradicts the doctrine, such as when Jesus states that the Father is greater than he is, or the Pauline theology: "Yet to us there is one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we unto him; and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and we through him."

- That it does not follow the strict monotheism found in Judaism and the Old Testament, of which Jesus claimed to have fulfilled.

- That it reflects the influence of pagan religions, some of which have divine triads of their own.

- That a triune God is a heavenly substitute for the human family for people, like monks and nuns, that have no earthly family.[15]

Since trinitarianism is central to so much of church doctrine, nontrinitarians have mostly been groups that existed before the Nicene Creed was codified in 325 or are groups that developed after the Protestant Reformation, when many church doctrines came into question.

In the early centuries of Christian history, Arians, Ebionites, Gnostics, Marcionites, and others held nontrinitarian beliefs. After the Nicene Creed raised the issue of the relationship between Jesus' divine and human natures, Monophysitism ("one nature") and monothelitism ("one will") were heretical attempts to explain this relationship. During more than a thousand years of trinitarian orthodoxy, formal nontrinitarianism, i.e., a nontrinitarian doctrine held by a church, group, or movement, was rare, but it did appear, for example, among the Cathars of the thirteenth century. The Protestant Reformation of the 1500s also brought tradition into question, although at first, nontrinitarians were executed (such as Servetus), or forced to keep their beliefs secret (such as Isaac Newton). The eventual establishment of religious freedom, however, allowed nontrinitarians to more easily preach their beliefs, and the nineteenth century saw the establishment of several nontrinitarian groups in North America and elsewhere. These include Christadelphians, Christian Scientists, Jehovah's Witnesses, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Unitarians. Twentieth-century nontrinitarian movements include Iglesia ni Cristo, and Oneness Pentecostals. Nontrinitarian groups differ from one another in their views of Jesus Christ, depicting him variously as a divine being second only to God the Father, Yahweh of the Hebrew Bible in human form, God (but not eternally God), prophet, or simply a holy man. It is interesting to note that nontrinitarians are basically of two types: the type of Modalistic Monarchianism and the type of Dynamistic Monarchianism.

Non-Christian Views of the Trinity

The concept of the Trinity has evoked mixed reactions in other world religions. Followers of Islam have often denounced this Christian doctrine as a corruption of pure monotheism. They see the doctrine as "evidence" that Christianity has fallen away from the true path of worshiping the one and only God, Allah. Muslim rejection of the Trinity concept is sometimes associated with the view that Christians are misguided polytheists. However, when the Qur'an speaks of the "trinity," it refers to God, Jesus and Mary—a threesome that is not recognizable as the Christian Trinity. Hence there may be room for dialogue on this issue.

Other religions have embraced a much more positive attitude towards the Trinity. Correspondences with parallel "threefold" concepts in non-Christian religions have been the foci of much inter-religious dialogue over the last century. For instance, the concept of Trimurti (three forms of God) in Hinduism has been an active topic in much Hindu-Christian dialogue. Additional discussions centering on the Trinity have addressed how the doctrine relates to Hindu understandings of the supreme Brahman as "Sat-Cit-Ananda" (absolute truth, consciousness and bliss).