Neanderthal

| Neanderthals | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. neanderthalensis La Ferrassie 1 H. neanderthalensis La Ferrassie 1

| ||||||||||||||

|

Prehistoric

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| †Homo neanderthalensis King, 1864 | ||||||||||||||

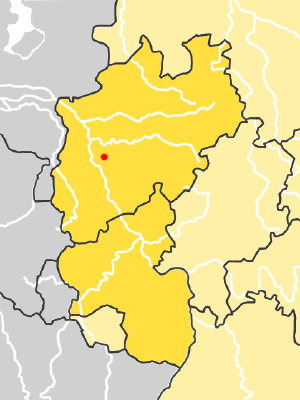

| Neanderthal range Neanderthal range

| ||||||||||||||

|

Palaeoanthropus neanderthalensis |

Neanderthal or Neandertal is an extinct species (Homo neanderthalensis) of the Homo genus that inhabited Europe and parts of western Asia from about 250,000 years ago until as recent as 30,000 years ago. At that point, they disappeared from the fossil record, being replaced by modern Homo sapiens. Neanderthal and Neadertal are optional spellings, but Neanderthal is more common in English and in scientific literature.

There is ongoing debate over whether '"Neanderthal" should be classified as a separate species, Homo neanderthalensis, or as a subspecies of H. sapiens, labeled as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis. The classification as a subspecies was popular in the 1970s and 1980s, but today many list them as separate species (Smithsonian 2007b).

Fossils of Neanderthals were first found in the 18th century prior to Charles Darwin's publication of the Origin of Species in 1859, with discoveries at Engis, Belgium in 1829, at Forbes Quarry, Gibraltar in 1848, and most notably a discovery in 1856 in Neander Valley in Germany, which was published in 1857. However, earlier findings were widely misinterpreted as skeletons of modern humans with deformaties or disease (Gould 1990). The new species H. neanderthalensis was recognized in 1864.

Mayr (2001) claims that Neanderthals arose from Homo erectus: "There is little doubt that . . . the western populations of H. erectus eventually gave rise to the Neanderthals." The issue of whether or how much Neanderthals contributed to the modern human genome is unsettled and remains vigorously debated (Kreger 2005). Krings et al. (1997) concluded from genetic studies that Neanderthals did not contribute genetic material to modern humans, while Kreger (2005) noted that the issue "is not as cut and dry" as is oftentimes claimed and it seems "highly unlikely that the Neanderthals contributed absolutely nothing to the modern genome." Equally unsettled is why the Neanderthals dissappeared.

Kreger (2005) notes that more argument is focused on Neaderthal by academia of paleoanthropology than any other species.

Overview

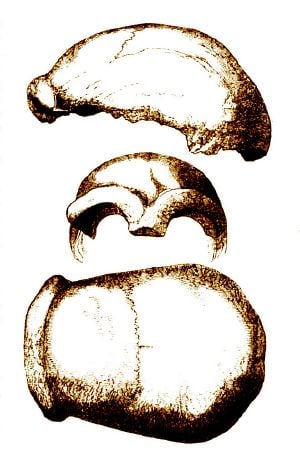

The August day in 1856 when a fossil was discovered in a limestone quarry in Germany is heralded as the beginning of paleoanthropology as a scientific discipline (Kreger 2005). This discovery of a skullcap and partial skeleton in a cave in the Neander Valley (near Dusseldorf) signaled the first recognized fossil human form (Smithsonian 2007b). In reality, it was not the first discovery of Neanderthal fossils, as skulls were discovered in Engis, Belgium in 1829 and Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar in 1848. However, these earlier discoveries were not recognized as belonging to archaic forms.

The type specimen, dubbed Neanderthal 1, consisted of a skull cap, two femora, three bones from the right arm, two from the left arm, part of the left ilium, fragments of a scapula, and ribs. The workers who recovered this material originally thought it to be the remains of a bear. They gave the material to amateur naturalist Johann Karl Fuhlrott, who turned the fossils over to anatomist Hermann Schaffhausen. The discovery was jointly announced in 1857. In 1864, a new species was recognized: Homo neanderthalensis.

These and subsequent discoveries led to the idea that these remains were from ancient Europeans who had played an important role in modern human origins. The bones of over 400 Neanderthals have been found since.

The term Neanderthal Man was coined by Irish anatomist William King, who first named the species in 1863 at a meeting of the British Association, and put it into print in the Quarterly Journal of Science in 1864 (Kreger 2005). The Neanderthal or "Neander Valley" itself was named after theologian Joachim Neander, who lived there in the late seventeenth century.

"Neanderthal" is now spelled two ways. The spelling of the German word Thal, meaning "valley or dale," was changed to Tal in the early 20th century, but the former spelling is often retained in English and always in scientific names, while the modern spelling is used in German. The original German pronunciation (regardless of spelling) is with the sound /t/. When used in English, the term is usually anglicised to /θ/ (as in thin), though speakers more familiar with German use /t/.

Classic Neanderthal fossils have been found over a large area, from northern Germany in the north, to Israel and Mediterranean countries like Spain and Italy in the south and from England in the west to Uzbekistan in the east. This area probably was not occupied all at the same time; the northern border of their range especially would have contracted frequently with the onset of cold periods. On the other hand, the northern border of their range as represented by fossils may not be the real northern border of the area that they occupied, since Middle-Palaeolithic looking artifacts have been found even further north, up to 60° on the Russian plain (Pavlov et al. 2004)

In Siberia, Middle Paleolithic populations are evidenced only in the southern portions. Teeth from Okladniko and Denisova caves have been attributed to Neanderthals (Goebel 1999). The transition to the Upper Paleolithic coincides with the appearance of modern Homo sapiens in Siberia. Early Upper Paleolithic sites in southern Siberia, found below 55 degrees latitude and dated from 42,000 to 30,000 B.P. (Before Present) correspond to the Malokheta interstade, a relatively warm interval in the mid-Upper Pleistocene (Goebel 1999).

Bischoff et al. (2003) report that the first proto-Neanderthal traits appeared in Europe as early as 350,000 years ago. By 130,000 years ago, full blown Neanderthal characteristics were present. Neanderthals became extinct in Europe approximately 30,000 years ago. There is recently discovered fossil and stone-tool evidence that suggests Neanderthals may have still been in existence 24,000 years ago, at which time they they disappeared from the fossil record and were replaced in Europe by modern Homo sapiens (Rincon 2006, Mcilroy 2006, Klein 2003, Smithsonian 2007b, 2007c).

There are a diversity of views on the disappearance of Neanderthals, including those related to rapid extinction, gradual extinction, and assimilation.

Neanderthal brain sizes have been estimated to be larger than modern humans, although such estimates have not been adjusted for their more robust builds. On average, Neanderthal males stood about 1.65 m tall (just under 5' 5") and were heavily built with robust bone structure. Females were about 1.53 to 1.57 m tall (about 5'–5'2").

Classification

For many years, professionals vigorously debated about whether Neanderthals should be classified as Homo neanderthalensis or as Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, the latter placing Neanderthals as a subspecies of Homo sapiens.

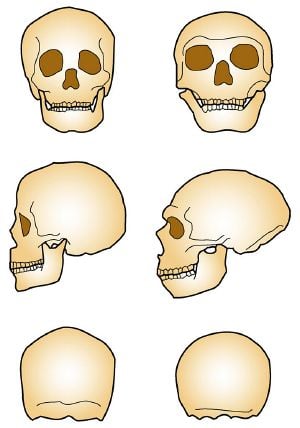

Smithsonian b: The original interpretation of Neanderthal anatomy was one of a primitive early human based on a flawed reconstruction of the nearly complete skeleton of an elderly Neanderthal male found at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France (second photograph from the top). However, Neanderthals and modern humans (Homo sapiens) are very similar anatomically — so similar, in fact, that in 1964, it was proposed that Neanderthals are not even a separate species from modern humans, but that the two forms represent two subspecies: Homo sapiens neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens sapiens. This classification was popular through the 1970's and 80's, although many authors today have returned to the previous two-species hypothesis. Either way, Neanderthals represent a very close evolutionary relative of modern humans.

Smithsonian c: The distinction between Neanderthals and modern humans was supported early on by a faulty reconstruction showing bent knees and a slouching gait. This reconstruction was responsible for the standard picture of the Neanderthals' supposedly crude caveman lifestyle. This image turned out to be mistaken. The Neanderthals walked fully upright without a slouch or bent knees. Their cranial capacity was large, around 1500 cc (slightly larger on average than the brains of modern populations, a difference probably related to their large bodies and lean muscle mass). They were also culturally sophisticated compared with earlier humans. They made finer tools and were the first humans known to bury their dead and to have symbolic ritual. The practice of intentional burial is one reason why Neanderthal fossils, including a number of skeletons, are quite common compared to earlier forms of Homo.

Smithsonian C: Nevertheless, Neanderthals differed from modern populations in certain ways. Their skulls showed a low forehead, large nasal area, projecting cheek region, double-arched brow ridge, weak chin, and an obvious space behind the third molar (in front of the upward turn of the mandible, or lower jaw). Their bodies were distinguished by these traits: heavily-built bones, occasional bowing of the limb bones, broad scapula (shoulder blade), hip joint rotated outward, long and thin pubic bone, short lower leg and arm bones relative to the uppers, and large joint surfaces of the toes and long bones. Together, these traits made a powerful, compact body of short stature — males averaged 1.7 m (5ft 5 in) tall and 84 kg (185 lb.), and females averaged 1.5 m (5 ft) tall and 80 kg (176lb).

the prevailing view of evidence, collected by examining mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosomal DNA, currently indicates that little or no gene flow occurred between H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens, and, therefore, the two were separate species. classification was popular through the 1970's and 80's, but now generally seen as separate

However, recent evidence from mitochondrial DNA studies have been interpreted as evidence that Neanderthals were not a subspecies of H. sapiens.[1] Some scientists, for example Milford Wolpoff, argue that fossil evidence suggests that the two species interbred, and hence were the same biological species. Others, for example Cambridge Professor Paul Mellars, say "no evidence has been found of cultural interaction".[2]

Krings et. al. (1997) found in genetic studies that Neanderthals and modern humans diverged genetically 500,000 to 600,000 years ago, suggesting that though they may have lived at the same time, Neanderthals did not contribute genetic material to modern humans. One of the participants of this study concluded: "These results [based on mitochondrial DNA extracted from Neanderthal bone] indicate that Neanderthals did not contribute mitochondrial DNA to modern humans… Neanderthals are not our ancestors" (PSU 1997). Subsequent investigation of a second source of Neanderthal DNA supported these findings. However, supporters of the multiregional hypothesis point to recent studies indicating non-African nuclear DNA heritage dating to one mya, as well as apparent hybrid fossils found in Portugal and elsewhere, in rebuttal to the prevailing view.

Kreger: This species is the focus of more argument among the academia of paleoanthropology than any other. Today, most researchers follow a multiregional view which has the European Neanderthals interbreeding and being absorbed by invading populations, or to have been marginalized by invading Homo sapiens until they died out, leaving no genetic legacy to modern humans. There are some (C.L. Brace most prominently) that think that the Neanderthals evolved in place into modern Europeans with little or no genetic influx from African populations, but few accept this argument.

Kreger: The eventual fate of the Neanderthals in the modern human phylogeny is still a much questioned issue, and a vigorously debated one. However, one thing is certain, the issue is not as cut and dry as many supporters of the Out of Africa II theory oftentimes claim. It seems highly unlikely that the Neanderthals contributed absolutely nothing to the modern genome, but whether they left a large heritage in modern humans or an insignificant one is a question that might not be answered satisfactorily for a long time.

Anatomy

The following is a list of physical traits that distinguish Neanderthals from modern humans; however, not all of them can be used to distinguish specific Neanderthal populations, from various geographic areas or periods of evolution, from other extinct humans. Also, many of these traits occasionally manifest in modern humans, particularly among certain ethnic groups. Nothing is known about the skin color, the hair, or the shape of soft parts such as eyes, ears, and lips of Neanderthals.[3]

Kreger (2005): They possessed several traits that have been used either as indicators of Neanderthal ancestry, or as autapomorphic Neanderthal traits. Some of these traits include:

An occipital bun. A suprainiac fossa. Position of the mastoid crest. Position of the juxtamastoid crest. Position of the mastoid process. The supraorbital torus. The supratoral sulcus. A receding frontal. Presence of lambdoidal flattening.

Compared to modern humans, Neanderthals were similar in height but more robust than modern humans, and had distinct morphological features, especially of the cranium, which gradually accumulated more derived aspects, particularly in certain relatively isolated geographic regions. Evidence suggests that they were much stronger than modern humans;[citation needed] their relatively robust stature is thought to be an adaptation to the cold climate of Europe during the Pleistocene epoch.

| Cranial | Sub-cranial |

|---|---|

| Suprainiac fossa, a groove above the inion | Considerably more robust |

| Occipital bun, a protuberance of the occipital bone that looks like a hair knot | Large round finger tips |

| Projecting mid-face | Barrel-shaped rib cage |

| Low, flat, elongated skull | Large kneecaps |

| A flat basic cranium | Long collar bones |

| Supraorbital torus, a prominent, trabecular (spongy) browridge | Short, bowed shoulder blades |

| 1200-1750 cm³ skull capacity (10% greater than modern human average) | Thick, bowed shaft of the thigh bones |

| Lack of a protruding chin (mental protuberance; although later specimens possess a slight protuberance) | Short shinbones and calf bones |

| Crest on the mastoid process behind the ear opening | Long, gracile pelvic pubis (superior pubic ramus) |

| No groove on canine teeth | |

| A retromolar space posterior to the third molar | |

| Bony projections on the sides of the nasal opening | |

| Distinctive shape of the bony labyrinth in the ear | |

| Larger mental foramen in mandible for facial blood supply | |

| A broad, projecting nose |

Based on a 2001 study, some commentators speculated that Neanderthals had red hair, and that some red-headed and freckled humans today share some heritage with Neanderthals;[4] however, many other researchers disagree.[5]

Neanderthals had many adaptations to a cold climate, such as large braincase, short but robust builds, and large noses — traits selected by nature in cold climates.

Language

The idea that Neanderthals lacked complex language was widespread, despite concerns about the accuracy of reconstructions of the Neanderthal vocal tract, until 1983, when a Neanderthal hyoid bone was found at the Kebara Cave in Israel. The hyoid is a small bone that connects the musculature of the tongue and the larynx, and by bracing these structures against each other, allows a wider range of tongue and laryngeal movements than would otherwise be the case. Therefore, it seems to imply the presence of anatomical conditions for speech to occur. The bone that was found is virtually identical to that of modern humans.[6]

Furthermore, the morphology of the outer and middle ear of Neanderthal ancestors, Homo heidelbergensis, found in Spain, suggests they had an auditory sensitivity similar to modern humans and very different from chimpanzees. Therefore, they were not only able to produce a wide range of sounds, they were also able to differentiate between these sounds. [7]

Aside from the morphological evidence above, neurological evidence for potential speech in neanderthalensis exists in the form of the hypoglossal canal. The canal of neanderthalensis is the same size or larger than in modern humans, which are significantly larger than the canal of modern chimpanzees and australopithecines. The canal carries the hypoglossal nerve, which supplies the muscles of the tongue with motor coordination. Researchers indicate that this evidence suggests that neanderthalensis had vocal capabilities similar to, or possibly exceeding that of, modern humans. [8] However, a research team from the University of California, Berkeley, led by David DeGusta, suggests that the size of the hypoglossal canal is not an indicator of speech. His team's research, which shows no correlation between canal size and speech potential, shows there are a number of extant non-human primates and fossilized australopithecines which have equal or larger hypoglossal canal. [9]

Many people believe that even without the hyoid bone evidence, tools as advanced as those of the Mousterian Era, attributed to Neanderthals, could not have been developed without cognitive skills encompassing some form of spoken language.

A great many myths surround the reconstruction of the Neanderthal vocal tract and the quality of Neanderthal speech. The popular view that the Neanderthals had a high larynx and therefore could not have produced the range of vowels supposedly essential for human speech is based on a disputed reconstruction of the vocal tract from the available fossil evidence, and a debatable interpretation of the acoustic characteristics of the reconstructed vocal tract. A larynx position as low as that found for modern female humans may have been present in adult male Neanderthals. Furthermore, the vocal tract is a plastic thing, and larynx movement is possible in many mammals. Finally, the suggestion that the vowels /i, a, u/ are essential for human language (and that if Neanderthals lacked them, they could not have evolved a human-like language) ignores the absence of one of these vowels in very many human languages, and the occurrence of 'vertical vowel systems' which lack both /i/ and /u/.

More doubtful suggestions about Neanderthal speech suggest that it would have been nasalised either because i) the tongue was high in the throat (for which there is no universally accepted evidence), or ii) because the Neanderthals had large nasal cavities. Nasalisation depends on neither of these things, but on whether or not the soft palate is lowered during speech. Nasalisation is therefore controllable, and we have no idea whether Neanderthal speech was nasalised or not. Comments on the lower intelligibility of nasalised speech ignore the fact that many varieties of English habitually have nasalised vowels, particularly low vowels, with no apparent effect on intelligibility.

Finally, suggestions that a 'stout larynx' would result in a higher rate of vibration of the vocal folds and hence a higher percept of pitch are erroneous [citation needed]. If the existence of a 'stout larynx' suggests large vocal folds, these would vibrate relatively slowly, and therefore give a percept of a lower pitch. Any comment about 'pitch levels' ignores the fact that the rate of vocal fold vibration can be changed by altering the tension in the vocal folds and by changing subglottal pressure. In other words, whatever the biological characteristics of the vocal folds, Neanderthal speech would be likely to have shown variation in the rate of vocal fold vibration (perceived as pitch), just as human speech or other mammalian vocalisations, and a non-biologically determined average or default pitch level could have been adopted by actively changing the 'neutral' state of the vocal folds.

One anatomical difference between Neanderthals and humans, that deserves consideration regarding human speech, is the mental tubercle on the mandible (the point at the tip of the chin), which is the attachment point for the depressor labii inferioris muscle and the mentalis muscle. These two muscles provide fine motor control of the lower lip, and are essential in controlled speech. The mental tubercle is pronounced in humans and is absent in Neanderthals, suggesting that they has a more gross motor control of the lower lip. More work needs to be done on this topic.

Tools

Neanderthal (Middle Paleolithic) archaeological sites show a smaller and different toolkit than those which have been found in Upper Paleolithic sites, which were perhaps occupied by modern humans that superseded them. Fossil evidence indicating who may have made the tools found in Early Upper Paleolithic sites is still missing.

There is little evidence that Neanderthals used antlers, shell, or other bone materials to make tools; their bone industry was relatively simple. However, there is good evidence that they routinely constructed a variety of stone implements. The Neanderthal (Mousterian) tool kits consisted of sophisticated stone-flakes, task-specific hand axes, and spears. Many of these tools were very sharp. There is also good evidence that they used a lot of wood, objects which are unlikely to have been preserved until today. [10]

Also, while they had weapons, none have yet been found that were used as projectile weapons. They had spears, in the sense of a long wooden shaft with a spearhead firmly attached to it, but these were not spears specifically crafted for flight (perhaps better described as a javelin). However, a number of 400,000 year old wooden projectile spears were found at Schöningen in northern Germany. These are thought to have been made by the Neanderthal's ancestors, Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis. Generally, projectile weapons are more commonly associated with H. sapiens. The lack of projectile weaponry is an indication of different sustenance methods, rather than inferior technology or abilities. The situation is identical to that of native New Zealand Maoris - modern Homo sapiens, who also rarely threw objects, but used spears and clubs instead. [11]

Although much has been made of the Neanderthal's burial of their dead, their burials were less elaborate than those of anatomically modern humans. The interpretation of the Shanidar IV burials as including flowers, and therefore being a form of ritual burial,[12] has been questioned.[13] On the other hand, five of the six flower pollens found with Shanidar IV are known to have had 'traditional' medical uses, even among relatively recent 'modern' populations. In some cases Neanderthal burials include grave goods, such as bison and aurochs bones, tools, and the pigment ochre.

Neanderthals performed a sophisticated set of tasks normally associated with humans alone. For example, they constructed complex shelters, controlled fire, and skinned animals. Particularly intriguing is a hollowed-out bear femur that contains holes that may have been deliberately bored into it. This bone was found in western Slovenia in 1995, near a Mousterian fireplace, but its significance is still a matter of dispute. Some paleoanthropologists have postulated that it might have been a flute while some others have expressed that it is natural bone modified by bears. See: Divje Babe.

The characteristic style of stone tools in the Middle Paleolithic is called the Mousterian Culture, after a prominent archaeological site where the tools were first found. The Mousterian culture is typified by the wide use of the Levallois technique. Mousterian tools were often produced using soft hammer percussion, with hammers made of materials like bones, antlers, and wood, rather than hard hammer percussion, using stone hammers. Near the end of the time of the Neanderthals, they created the Châtelperronian tool style, considered more advanced than that of the Mousterian. They either invented the Châtelperronian themselves or borrowed elements from the incoming modern humans who are thought to have created the Aurignacian.

Middle Paleolithic industries in Siberia (dated to 70,000 to 40,000 years ago) are distinctly Levallois and Mousterian, reduction technologies are uniform, and assemblages consist of scrapers, denticulates, notches, knives, and retouched Levallois flakes and points, and there is no evidence of bone, antler or ivory technology, or of art or personal adornment (Goebel 1999).

Subprismatic blade and flake primary reduction technology characterizes the lithic industry, and microblade cores are absent. The Mousterian flake and simple biface industry that characterizes the Middle Paleolithic, wherever found with human remains, is found with Neanderthals, and wherever Aurignacian is found with remains, it is found with modern humans.[14]

Ritual defleshing or cannibalism

Intentional burial and the inclusion of grave goods is the most typical representation of ritual behaviour in the Neanderthals and denote a developing ideology. However, another much debated and controversial manifestation of this ritual treatment of the dead comes from the evidence of cut-marks on the bone which has historically been viewed as evidence of cannibalism. Neanderthal bones from various sites (Combe-Grenal and Abri Moula in France, Krapina in Croatia and Grotta Guattari in Italy) have all been cited as bearing cut marks made by stone tools.[15] However, re-evaluation of these marks using high-powered microscopes, comparisons to contemporary butchered animal remains and recent ethnographic cases of excarnation mortuary practises have shown that perhaps this was a case of ritual defleshing. Fragments of bones from Krapina bear marks that are similar to those seen on bones from secondary burials at a Michigan ossuary (14th century AD) and are indicative of removing the flesh of a partially decomposed body. At Grotta Guattari, the apparently purposefully widened base of the skull (for access to the brains) has been shown to be caused by carnivore action, with hyena tooth marks found on the skull and mandible. However, analysis of the bones from Abri Moula in France does seem to suggest cannibalism was practiced here. This is the case since cut-marks are concentrated in the places where one would expect them in the case of butchery, instead of defleshing. Additionally the treatment of the bones was similar to that of roe deer bones, assumed to be food remains, found in the same shelter.[16] The evidence indicating cannibalism would not necessarily distinguish Neanderthals from modern Homo sapiens. Existing Homo sapiens tribes are known to practice cannibalism and mortuary defleshing.

Pathology

Within the west Asian and European record there are five broad groups of pathology or injury noted in Neanderthal skeletons.

Fractures

Neanderthals seemed to suffer a high frequency of fractures, especially common on the ribs (Shanidar IV, La Chapelle-aux-Saints ‘Old Man’), the femur (La Ferrassie 1), fibulae (La Ferrassie 2 and Tabun 1), spine (Kebara 2) and skull (Shanidar I, Krapina, Sala 1). These fractures are often healed and show little or no sign of infection, suggesting that injured individuals were cared for during times of incapacitation. The pattern of fractures has been found to be similar to modern rodeo clowns which, along with the absence of throwing weapons, suggests that they may have hunted by leaping onto their prey and stabbing or even wrestling it to the ground.

Trauma

Particularly related to fractures are cases of trauma seen on many skeletons of Neanderthals. These usually take the form of stab wounds, as seen on Shanidar III, whose lung was probably punctured by a stab wound to the chest between the 8-9th ribs. This may have been an intentional attack or merely a hunting accident; either way the man survived for some weeks after his injury before being killed by a rock fall in the Shanidar cave. Other signs of trauma include blows to the head (Shanidar I and IV, Krapina), all of which seemed to have healed, although traces of the scalp wounds are visible on the surface of the skulls.

Degenerative Disease

Arthritis is particularly common in the older Neanderthal population, specifically targeting areas of articulation such as the ankle (Shanidar III), spine and hips (La Chapelle-aux-Saints ‘Old Man’), arms (La Quina 5, Krapina, Feldhofer) knees, fingers and toes. This is closely related to degenerative joint disease, which can range from normal, use-related degeneration to painful, debilitating restriction of movement and deformity and is seen in varying degree in the Shanidar skeletons (I-IV).

Hypoplastic Disease

Dental enamel hypoplasia is an indicator of stress during the development of teeth and records in the striations and grooves in the enamel periods of food scarcity, trauma or disease. A study of 669 Neanderthal dental crowns showed that 75% of individuals suffered some degree of hypoplasia and the nutritional deficiencies were the main cause of hypoplasia and eventual tooth loss. All particularly aged skeletons show evidence of hypoplasia and it is especially evident in the Old Man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints and La Ferrassie 1 teeth.

Infection

Evidence of infections on Neanderthal skeletons is usually visible in the form of lesions on the bone, which are created by systematic infection on areas closest to the bone. Shanidar I has evidence of the degenerative lesions as does La Ferrassie 1, whose lesions on both femora, tibiae and fibulae are indicative of a systemic infection or carcinoma (malignant tumour/cancer).

The fate of the Neanderthals

The Neanderthals began to be displaced around 45,000 years ago by modern humans (Homo sapiens), as the Cro-Magnon people appeared in Europe. Despite this, populations of Neanderthals held on for thousands of years in regional pockets such as modern-day Croatia and the Iberian and Crimean peninsulas. The last known population lived around a cave system on the remote south facing coast of Gibraltar, from 30,000 to 24,000 years ago.

The Neanderthals began to be displaced around 45,000 years ago by modern humans (Homo sapiens), as the Cro-Magnon people appeared in Europe. Despite this, populations of Neanderthals held on for thousands of years in regional pockets such as modern-day Croatia and the Iberian and Crimean peninsulas.

There is considerable debate about whether Cro-Magnon people accelerated the demise of the Neanderthals. Timing suggests a causal relation between the appearance of Homo sapiens in Europe and the decline of Homo neanderthalensis. Both the Neanderthals' place in the human family tree and their relation to modern Europeans have been hotly debated ever since their discovery. They have been classified as a separate species (Homo neanderthalensis) and as a subspecies of Homo sapiens (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) at different times. The consensus has been, based on ongoing DNA research, that they were a separate branch of the genus Homo, and that modern humans are not descended from them (fitting with the single-origin hypothesis).

In some areas of the Middle East and the Iberian peninsula, Neanderthals did, in fact, co-exist side by side with populations of anatomically modern Homo sapiens for roughly 10,000 years. There is also evidence that it is in these areas where the last of the Neanderthals died out and that during this period the last remnants of this species had begun to adopt — or perhaps independently innovate — some aspects of the Châtelperronian (Upper Paleolithic) tool case, which is usually exclusively associated with anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

Extinction scenarios

Rapid extinction

Jared Diamond has suggested a scenario of violent conflict, comparable to the genocides suffered by indigenous peoples in recent human history.

Another possibility paralleling colonialist history would be a greater susceptibility to pathogens introduced by Cro-Magnon man on the part of the Neanderthals. Although Diamond and others have specifically mentioned Cro-Magnon diseases as a threat to Neanderthals, this aspect of the analogy with the contacts between colonisers and indigenous peoples in recent history can be misleading. The distinction arises because Cro-Magnons and Neanderthals are both believed to have lived a nomadic lifestyle, whereas in those genocides of the colonial era in which differential disease susceptibility was most significant, it resulted from the contact between colonists with a long history of agriculture and nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples. Diamond argues that asymmetry in susceptibility to pathogens is a consequence of the difference in lifestyle, which makes it irrelevant in the context of the analogy in which he invokes it.

On the other hand, many Native Americans before contact with Europeans were not nomadic, but agriculturalists (Mayans, Iroquois, Cherokee), and this still did not protect them from the disease epidemics brought by Europeans (Smallpox). One theory is that because they usually lacked large domesticated animal agriculture, such as cows or pigs in close contact with people (Zoonosis), they did not develop resistance to species-jumping diseases like Europeans had. See also Guns, Germs, and Steel.[17] Furthermore, the nomadic Eurasian populations such as the Mongols did not get wiped out by the diseases of the agriculturalist societies they invaded and took over, like China and eastern Europe. The situation is complicated.

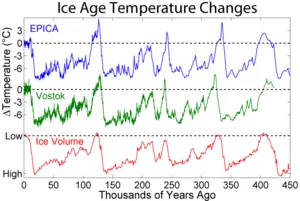

Gradual extinction

However, these scenarios may be more drastic than is required to explain a decline of Neanderthal population over the course of some 10,000 years: even a slight selective advantage on the part of modern humans could account for Neanderthals' replacement on such a timescale. Gradual climatic change as a cause of extinction is also a common hypothesis. Speech-related theories have been largely discredited.[citation needed]

The problem with a gradual extinction scenario lies in the resolution of dating methods. There have been claims for young Neanderthal sites, younger than 30,000 years old.[18] Even claims for interstratification of Neanderthal and Modern human remains have been advanced[19] So the fact that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted at least for some time seems certain. However, because of difficulties in calibrating the C14 dates the duration of this period is uncertain[20]

Assimilation

One skeleton that has led some researchers to claim that it shared Neanderthal and Cro-magnon features has been found at Lagar Velho in Portugal; it is uncertain whether this is in fact a hybrid of the two species, or simply an extreme individual of one or the other. This may suggest the two species may have interbred. The child skeleton does seem to be more robust than what we would expect for modern humans. However, most researchers think that it represents extreme variation within modern humans. Moreover, the skeleton is dated to about 24,000 years BP. Until recently, this implied that a hybrid population survived in the region for thousands of years.[21] However, a Neanderthal population in Gibraltar dated to about the same time has recently been found.[22] The dating evidence for this claim is debated, though.[23] Claims for Neanderthal sites that were advanced in the past have in the end all been revised to pre-30 kyr. It has also been speculated that these hybrid individuals could have been sterile.

It is very difficult to prove as the genetic differences between Neanderthals and Cro-magnons were far more minute than the morphological differences between the two species might seem to indicate. Tests comparing Neanderthal and modern human mitochondrial DNA show some dissimilarity. The mtDNA indicated a split between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals occurred more than 500,000 years ago. This can be compared with the 1 million years split between various canine species, which still can interbreed. Morphological symmetry and asymmetry often belies genetic truth in the case of these ancient Homo populations. In any case it is possible that the Neanderthals, with their small populations, could have been absorbed by the much larger populations of modern Homo sapiens.[citation needed] These hybrid remains should not be confused with Homo heidelbergensis, the more ancient possible ancestor of the Neanderthal. It is possible that differences in behavior rather than biological sterility contributed to low or non-existent interbreeding. But another possibility is that the Cro-magnons that have interbred with the Neanderthals are no longer under us. When agriculture came into Europe, bringing the late stone-age, the hunter-gatherers that lived in Europe first may have been driven away, or have in their turn been absorbed by the larger population of newcomers. There may although still be pockets of those people present, most prominent candidate are the Basques.

Based on an Oxford University 2001 study of the gene that results in red-headedness,[24] some commentators speculated that Neanderthals had red hair and that some red-headed and freckled humans today share some heritage with Neanderthals;[25] however, other researchers disagree,[26] and the scientists who conducted the study claim this is a misinterpretation of their findings.[27]

In November 2006, a paper was published in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in which a team of European researchers report that Neanderthals and humans interbred. Co-author Erik Trinkaus from Washington University explains, "Closely related species of mammals freely interbreed, produce fertile viable offspring and blend populations." The study claims to settle the extinction controversy; according to researchers, the human and neanderthal populations blended together through sexual reproduction. Trinkaus states, "Extinction through absorption is a common phenomenon."[28] and "From my perspective, the replacement vs. continuity debate that raged through the 1990s is now dead".[29]

Unable to adapt

European populations of neanderthalensis were adapted for a cold environment. Thus they may have had problems adapting to a warming environment. The problem with this idea is that the glacial period of our ice age ended about 10,000 years ago, while the Neanderthals went extinct about 24,000 years ago.

Another possibility has to do with the loss of the Neanderthal's primary hunting territory - forests. The Neanderthals hunted by stabbing their prey with spears (as opposed to throwing the spears at their prey). They were also far less mobile than modern humans.[citation needed] So when the forests were gradually replaced by flat lands, the Neanderthals would have had great difficulty hunting. In the open they would not have been able to stalk their prey, their stabbing weapons would have been largely useless, and they - unlike modern humans - could not easily chase their prey. Also, modern humans are omnivores. The way the Neanderthals were built suggests that they need a lot of energy. Injuries in found skeletons suggest that both males and females hunted. Together, this suggests that Neanderthals ate meat only, and were therefore less adaptable. The same thing is seen in the wolf family, where smaller species, like foxes, usually held out longer than the larger species, which are dependent on big prey and specific hunting environments like Neanderthals. Homo sapiens, which hunted large prey but did not depend on them for survival, may have helped them into extinction this way.

Dr. Myra Shackley has speculated that a surviving population of Neanderthals may be the Almas: a wild man reported in the Caucasus and other regions. This view is generally regarded as speculative and highly unlikely.[citation needed]

Division of labor

In 2006, anthropologists Steven L. Kuhn and Mary C. Stiner of the University of Arizona proposed a new explanation for the demise of the Neanderthals.[30] In an article titled "What's a Mother to Do? The Division of Labor among Neanderthals and Modern Humans in Eurasia",[31] they theorise that Neanderthals did not have a division of labor between the sexes. Both male and female Neanderthals participated in the single main occupation of hunting big game that flourished in Europe in the ice age like bison, deer, gazelles and wild horses. This contrasted with humans who were better able to use the resources of the environment because of a division of labor with the women going after small game and gathering plant foods. In addition because big game hunting was so dangerous this made humans, at least females, more resilient (see also Peter Frost's theory on the origins of European blond hair).

Genome

In July 2006, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and 454 Life Sciences announced that they would be sequencing the Neanderthal genome over the next two years. At three billion base pairs, the Neanderthal genome is roughly the size of the human genome and likely shares many identical genes. It is thought that a comparison of the Neanderthal genome and human genome will expand understanding of Neanderthals as well as the evolution of humans and human brains.[32]

DNA researcher Svante Paabo has tested more than 70 Neanderthal specimens and found only one that had enough DNA to sample. Preliminary DNA sequencing from a 38,000 year old bone fragment of a femur bone found at a Croatian Vindija Cave in 1980 shows that Neanderthalis and Homo sapiens share about 99.5% of their DNA. It is believed that the two species shared a common ancestor about 500,000 years ago. The journal Nature has calculated the species diverged about 516,000 years ago, whereas fossil records show a time of about 400,000 years ago. From DNA records, scientists hope to falsify or confirm the theory that there was interbreeding between the species.[33]

Edward Rubin of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, California states that recent genome testing of Neanderthals suggests human and Neanderthal DNA are some 99.5 percent to nearly 99.9 percent identical.[34][35]

In November 2006, a paper was published in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in which a team of European researchers report that Neanderthals and humans interbred. Co-author Erik Trinkaus from Washington University explains, "Closely related species of mammals freely interbreed, produce fertile viable offspring, and blend populations." The study claims to settle the extinction controversy; according to researchers, the human and neanderthal populations blended together through sexual reproduction. Erik Trinkaus states, "Extinction through absorption is a common phenomenon."[36] and "From my perspective, the replacement vs. continuity debate that raged through the 1990s is now dead".[37]

Key dates

- 1829: Neanderthal skulls were discovered in Engis, Belgium.

- 1848: Skull of an ancient human was found in Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar. Its significance was not realized at the time.

- 1856: Johann Karl Fuhlrott first recognized the fossil called “Neanderthal man”, discovered in Neanderthal a valley near Mettmann in what is now North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany.

- 1880: The mandible of a Neanderthal child was found in a secure context and associated with cultural debris, including hearths, Mousterian tools, and bones of extinct animals.

- 1899: Hundreds of Neanderthal bones were described in stratigraphic position in association with cultural remains and extinct animal bones.

- 1908: A nearly complete Neanderthal skeleton was discovered in association with Mousterian tools and bones of extinct animals.

- 1953-1957: Ralph Solecki uncovered nine Neanderthal skeletons in Shanidar Cave in northern Iraq.

- 1975: Erik Trinkaus’s study of Neanderthal feet confirmed that they walked like modern humans.

- 1987: New thermoluminescence resulted from Palestine fossils date Neanderthals at Kebara to 60,000 BP and modern humans at Qafzeh to 90,000 BP. These dates were confirmed by Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) dates for Qafzeh (90,000 BP) and Es Skhul (80,000 BP).

- 1991: New ESR dates showed that the Tabun Neanderthal was contemporaneous with modern humans from Skhul and Qafzeh.

- 1997 Matthias Krings et al. are the first to amplify Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA using a specimen from Feldhofer grotto in the Neander valley. Their work is published in the journal Cell.

- 2000: Igor Ovchinnikov, Kirsten Liden, William Goodman et al. retrieved DNA from a Late Neanderthal (29,000 BP) infant from Mezmaikaya Cave in the Caucausus.

- 2005: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology launched a project to reconstruct the Neanderthal genome.

- 2006: The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology announced that it planned to work with Connecticut-based 454 Life Sciences to reconstruct the Neanderthal genome.

Popular culture

Popular literature has tended to greatly exaggerate the ape-like gait and related characteristics of the Neanderthals. It has been determined that some of the earliest specimens found in fact suffered from severe arthritis. The Neanderthals were fully bipedal and had a slightly larger average brain capacity than a typical modern human, though it is thought the brain structure may have been organized differently.

In popular idiom the word neanderthal is sometimes used as an insult, to suggest that a person combines a deficiency of intelligence and an attachment to brute force, as well as perhaps implying the person is old fashioned or attached to outdated ideas, much in the same way as "dinosaur" or "Yahoo" is also used. Counterbalancing this are sympathetic literary portrayals of Neanderthals, as in the novel The Inheritors by William Golding, Isaac Asimov's The Ugly Little Boy and Jean M. Auel's Earth's Children series, or the more serious treatment by palaeontologist Björn Kurtén, in several works including Dance of the Tiger, and British psychologist Stan Gooch in his hybrid-origin theory of humans.

See also

- Caveman

- List of neanderthal sites

- Neandertal interaction with Cro-Magnons

- Physical anthropology

- Abrigo do Lagar Velho - More about "the Lapedo child"

Notes

- ↑ Hodges, S. Blair (2000-12-07). Human Evolution: A start for population genomics. Nature Publishing Group.

- ↑ Modern humans, Neanderthals shared earth for 1,000 years. ABC News (Australia) (2005-09-01). Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ [http://www.livescience.com/history/050310_neanderthal_reconstruction.html Scientists Build 'Frankenstein' Neanderthal Skeleton]

- ↑ Red-Heads and Neanderthals (May 2001). Retrieved 2005-10-28.

- ↑ Nicole's hair secrets (2002-02-10). Retrieved 2005-11-02.

- ↑ B. Arensburg, A. M. Tillier, B. Vandermeersch, H. Duday, L. A. Schepartz & Y. Rak (April 1989). A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone. Nature (338): 758-760.

- ↑ Martinez, I., L. Rosa, J.-L. Arsuaga, P. Jarabo, R. Quam, C. Lorenzo, A. Gracia, J.-M. Carretero, J.M. Bermúdez de Castro, E. Carbonell (July 2004). Auditory capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain = PNAS 101 (27): 9976-9981.

- ↑ Richard F. Kay, Matt Cartmill, and Michelle Balow (April 1998). The hypoglossal canal and the origin of human vocal behavior. PNAS 95 (9): 5417-5419.

- ↑ David DeGusta, W. Henry Gilbert and Scott P. Turner (Feb 1999). Hypoglossal canal size and hominid speech. PNAS 96 (4): 1800-1804.

- ↑ Henig, Martin. "Odd man out: Neanderthals and modern humans." British Archeology, #51, Feb 2000. [1]

- ↑ Schwimmer, E.G. "Warfare of the Maori." Te Ao Hou: The New World, #36, Sept 1961, pp. 51-53. [2]

- ↑ R. S. Solecki (1975). Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal flower burial in northern Iraq. [[Science (journal)|]] 190 (28): 880.

- ↑ J. D. Sommer (1999). The Shanidar IV 'Flower Burial': A Reevaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual. Cambridge Archæological Journal 9: 127–129.

- ↑ West, Frederick Hadleigh (1996). "Beringia and New World Origins: The Archaeological Evidence", in Fredrick Hadleigh West (ed.): American Beginnings: The Prehistory and Paleoecology of Beringia. The University of Chicago Press, pp. 525-536.

- ↑ Andrea Thompson (2006-12-04). Neanderthals Were Cannibals, Study Confirms. Health SciTech. LiveScience.

- ↑ Defleur A, White T, Valensi P, Slimak L, Cregut-Bonnoure E (1999). Neanderthal cannibalism at Moula-Guercy, Ardèche, France. Science 286: 128-131.

- ↑ http://www.ilri.cgiar.org/ILRIPubAware/Uploaded%20Files/20048111016100.01BR_ISS_Non-ILRI_Diamond_EvolutionOfGerms(GunsGermsSteel).htm

- ↑ Finlayson, C., F. G. Pacheco, J. Rodriguez-Vidal, D. A. Fa, J. M. G. Lopez, A. S. Perez, G. Finlayson, E. Allue, J. B. Preysler, I. Caceres, J. S. Carrion, Y. F. Jalvo, C. P. Gleed-Owen, F. J. J. Espejo, P. Lopez, J. A. L. Saez, J. A. R. Cantal, A. S. Marco, F. G. Guzman, K. Brown, N. Fuentes, C. A. Valarino, A. Villalpando, C. B. Stringer, F. M. Ruiz, and T. Sakamoto. 2006. Late survival of Neanderthals at the southernmost extreme of Europe. Nature advanced online publication.

- ↑ Gravina, B., P. Mellars, and C. B. Ramsey. 2005. Radiocarbon dating of interstratified Neanderthal and early modern human occupations at the Chatelperronian type-site. Nature 438:51-56.

- ↑ Mellars, P. 2006. A new radiocarbon revolution and the dispersal of modern humans in Eurasia. Nature' 439:931-935.

- ↑ http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/lagarvelho.html

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/story/0,,1871842,00.html

- ↑ http://johnhawks.net/weblog/reviews/neandertals/gorhams_28000_date_2006.html

- ↑ http://www.dhamurian.org.au/anthropology/neanderthal1.html

- ↑ Red-Heads and Neanderthals (May 2001). Retrieved 2005-10-28.

- ↑ Nicole's hair secrets (2002-02-10). Retrieved 2005-11-02.

- ↑ http://www.ox.ac.uk/blueprint/2000-01/3105/11.shtml

- ↑ Humans and Neanderthals interbred

- ↑ Modern Humans, Neanderthals May Have Interbred

- ↑ Nicholas Wade, "Neanderthal Women Joined Men in the Hunt", from The New York Times, December 5, 2006

- ↑ Steven L. Kuhn and Mary C. Stiner, "What's a Mother to Do? The Division of Labor among Neandertals and Modern Humans in Eurasia", Current Anthropology, Volume 47, Number 6, December 2006

- ↑ Moulson, Geir. "Neanderthal genome project launches", MSNBC.com, Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/15/science/16neanderthalcnd.html

- ↑ Neanderthal bone gives DNA clues

- ↑ Scientists decode Neanderthal genes

- ↑ Humans and Neanderthals interbred

- ↑ Modern Humans, Neanderthals May Have Interbred

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Serre et al. (2004). No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans. PLoS Biology 2 (3): 313–7. PMID 15024415.

- http://www.ufoarea.com/evolution_bones.html

References

- Gould, S. J. 1990. Men of the Thirty-third Division. Natural History April, 1990: 12,14,16-18, 20, 22-24.

- Kreger, C. D. 2005. Homo neanderthalensis: Introduction. Archaeology.info. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- Krings, M., A. Stone, R. W. Schmitz, H. Krainitzki, M. Stoneking, and S. Pääbo. 1997. Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans. Cell 90(1): 19-30.

- Levy, S. 2006. Clashing with titans. BioScience 56(4): 295.

- Mayr, E. 2001. What evolution is. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465044255.

- Novaresio, P. 1996. The Explorers. Stewart, Tabori & Chang. ISBN 155670495X.

- Pennsylvania State University (PSU). 1997. DNA shows neandertals were not our ancestors. Penn State News. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- Sawyer, G. J., and B. Maley. 2005. Neanderthal Reconstructed. Anat. Rec. (New Anat.) 283B: 23-31.

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2007a. Homo erectus. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2007b. Homo neanderthalensis. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2007c. The Origin of the Genus Homo. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

.[1]

- Derev’anko, Anatoliy P. 1998 The Paleolithic of Siberia. New Discoveries and Interpretations. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- C. David Kreger (2000-06-30) Homo Neanderthalensis (archive link, was dead)

- Dennis O'Neil (2004-12-06) Evolution of Modern Humans Neandertals retrieved 12/26/2004

- Fink, Bob (1997) The Neanderthal Flute... (Greenwich, Canada) ISBN 0-912424-12-5

- Hickmann, Kilmer, Eichmann (ed.) (2003) Studies in Music Archaeology III International Study Group on Music Archaeology's 2000 symposium. ISBN 3-89646-640-2

- Serre et al. (2004). No evidence of Neandertal mtDNA contribution to early modern humans. PLoS Biology 2 (3): 313–7. PMID 15024415.

- Eva M. Wild, Maria Teschler-Nicola, Walter Kutschera, Peter Steier, Erik Trinkaus & Wolfgang Wanek (05 2005). Direct dating of Early Upper Palaeolithic human remains from Mladeč. Nature 435: 332–5. link for Nature subscribers

- Boë, Louis-Jean, Jean-Louis Heim, Kiyoshi Honda and Shinji Maeda. (2002) "The potential Neandertal vowel space was as large as that of modern humans." Journal of Phonetics, Volume 30, Issue 3, July 2002, Pages 465-484

- Lieberman, Philip. (in press, Sep 2006). "Current views on Neanderthal speech capabilities: A reply to Boe et al. (2002)" Journal of Phonetics.

- ↑ Pavlov, P., W. Roebroeks, and J. I. Svendsen (2004). The Pleistocene colonization of northeastern Europe: A report on recent research. Journal of Human Evolution 47 (1-2): 3-17. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.002.

- ↑ J. L. Bischoff et al. (2003). Neanderthals. J. Archaeol. Sci. (30): 275.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (2006-09-13). Neanderthals' 'last rock refuge'. BBC News. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ Mcilroy, Anne (2006-09-13). Neanderthals may have lived longer than thought. Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ Richard G. Klein (March 2003). PALEOANTHROPOLOGY: Whither the Neanderthals?. Science 299 (5612): 1525-1527.

- ↑ Goebel, Ted (1999). Pleistocene Human Colonization and Peopling of the Americas: An Ecological Approach. Evolutionary Anthropology 8 (6): 208-226.

External links

- Smithsonian

- Archaelogy Info

- MNSU

- "Humans and Neanderthals interbred": Modern humans contain a little bit of Neanderthal, according to a new theory, because the two interbred and became one species. (Cosmos magazine, November 2006)

- BBC.co.uk - 'Neanderthals "mated with modern humans": A hybrid skeleton showing features of both Neanderthal and early modern humans has been discovered, challenging the theory that our ancestors drove Neanderthals to extinction', BBC (April 21, 1999)

- BBC.co.uk - 'Neanderthals "had hands like ours": The popular image of Neanderthals as clumsy, backward creatures has been dealt another blow', Helen Briggs, BBC (March 27, 2003)

- GeoCities.com - 'The Neanderthal Sites at Veldwezelt-Hezerwater, Belgium'

- Greenwych.ca - 'Neanderthal Flute: Oldest Musical Instrument's 4 Notes Matches 4 of Do, Re, Mi Scale - Evidence of Natural Foundation to Diatonic Scale (oldest known musical instrument), Greenwich Publishing

- Greenwych.ca - 'Chewed or Chipped? Who Made the Neanderthal Flute? Humans or Carnivores?' Bob Fink, Greenwich Publishing (March, 2003)

- Humans Edged Out Neanderthals Earlier, Study Says

- IndState.edu - 'Neanderthals: A Cyber Perspective', Kharlena María Ramanan, Indiana State University (1997)

- Krapina.com - 'Krapina: The World's Largest Neanderthal Finding Site'

- Neanderthal.de - 'Neanderthal Museum'

- Neanderthal DNA - 'Neanderthal DNA' Includes Neanderthal mtDNA sequences

- The Cryptid Zoo - 'Neanderthals and Neanderthaloids in Cryptozoology' (modern sightings promoted by the pseudoscience of cryptozoology)

- UniZH.ch - 'Comparing Neanderthals and modern humans: Neanderthals differ from anatomically modern Homo sapiens in a suite of cranial features' (cranio-facial reconstructions), Institut für Informatik der Universität Zürich

- WebShots.com - 'IMG_6922 The Neandertal foot prints' (photo of ~25K years old fossilized footprints discovered in 1970 on volcanic layers near Demirkopru Dam Reservoir, Manisa, Turkey)

- interactive database on the archaeology and anthropology of Neanderthals

- At least 5% Neanderthal admixture in Europeans

- Did free trade cause the extinction of Neanderthals?

- Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA can show conflicting phylogenetic histories

- Neanderthal manifactured pitch

- Homo neanderthalensis reconstruction - Electronic articles published by the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

- CBS article on latest scientific speculation about Neanderthals in Gibraltar.

- Neanderthal bone gives DNA clues

- Scientists decode Neanderthal genes

- Scientists Build 'Frankenstein' Neanderthal Skeleton

- A NEANDERTHAL'S DNA TALE

- 'Bone and Stone' A digitally enhanced single frame philatelic exhibit dedicated to the Neanderthal.

- How Neanderthal molar teeth grew

- Mousterian Tools of Neanderthals From Europe - World Museum of Man

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.