Difference between revisions of "Magnetism" - New World Encyclopedia

(editing) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{2Copyedited}}{{Ebcompleted}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}} |

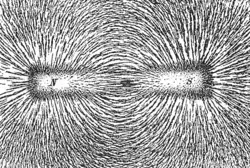

| − | [[Image:Magnet0873.png|thumb|250px|Magnetic lines of force of a bar magnet shown by iron filings on paper | + | [[Image:Magnet0873.png|thumb|250px|Magnetic lines of force of a bar magnet shown by iron filings on paper]] |

| − | |||

| − | + | In [[physics]], '''magnetism''' is one of the phenomena by which [[material]]s exert attractive and repulsive [[force]]s on other materials. It arises whenever electrically [[electric charge|charged particles]] are in [[Motion (physics)|motion]]—such as the movement of [[electron]]s in an [[electric current]] passing through a wire. | |

| − | + | Some well-known materials that exhibit readily detectable magnetic properties are [[iron]], some [[steel]]s, and the [[mineral]] lodestone (an oxide of iron). Objects with such properties are called '''magnets''', and their ability to attract or repel other materials at a distance has been attributed to a '''[[magnetic field]]'''. Magnets attract iron and some other metals because they imbue them temporarily with magnetic properties that disappear when the magnets are taken away. All materials are influenced to a greater or lesser extent by a magnetic field. | |

| + | Every magnet has two poles—or opposite parts—that show uniform force characteristics. The opposite poles of two magnets attract each other, but their similar poles repel each other. No magnet has ever been found to have only one pole. If a magnet is broken, new poles arise at the broken ends so that each new piece has a pair of north and south poles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Earth]] itself is a giant magnet. Its magnetic field shields living organisms by deflecting charged particles coming from the solar wind. In addition, people have taken advantage of this magnetic field for navigational purposes. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | With the development of [[technology]], the principles of magnetism have been applied for such purposes as storing information on computer disks, audiotapes, videotapes, and credit/debit cards; displaying images on [[television]] and [[computer]] screens; converting [[mechanical energy]] into [[electrical energy]] (as in [[electricity generator]]s and microphones); and converting electrical energy into mechanical energy (as in electric motors and loudspeakers). | ||

== History == | == History == | ||

| + | The phenomenon of magnetism has been known since ancient times, when it was observed that lodestone, an iron oxide mineral (Fe<sub>3</sub>O<sub>4</sub>) with a particular [[crystal]]line structure, could attract pieces of iron to itself. The early Chinese and Greeks, among others, found that when a lodestone is suspended horizontally by a string and allowed to rotate around a vertical axis, it orients itself such that one end points approximately toward true north. This end came to be called the ''north'' pole (north-seeking pole), while the opposite end was called the ''south'' pole (south-seeking pole). In addition, this observation led investigators to infer that the [[Earth]] itself is a huge magnet, with a pair of north and south magnetic poles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The mysteries of magnetic phenomena were documented and clarified by William Gilbert (1544-1603) in his treatise, ''De Magnete''. In the eighteenth century, [[Charles-Augustin de Coulomb]] (1736-1806) noted that the forces of attraction or repulsion between two magnetic poles can be calculated by an equation similar to that used to describe the interactions between electric charges. He referred to an "inverse square law," which (in the case of magnets) states that the force of attraction or repulsion between two magnetic poles is directly proportional to the product of the magnitudes of the pole strengths and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the poles. | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|The phenomenon of magnetism was known in ancient times but it was not until the nineteenth century that the connection was made between magnetism and [[electricity]]}} | ||

| + | === Connection between magnetism and electricity === | ||

| + | It was not until the nineteenth century, however, that investigators began to draw a connection between magnetism and electricity. In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) discovered that a [[compass]], which consists of a small magnet balanced on a central shaft, is deflected in the presence of an electric current. Building on this discovery, Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862) and Félix Savart (1791-1841) established that a current-carrying wire exerts a magnetic force that is inversely proportional to the distance from the wire. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[André-Marie Ampère]] (1775-1836) formulated an elegant mathematical expression that defined the link between an electric current and the magnetic force it generates. [[Michael Faraday]] (1791-1867) introduced the concept of lines of magnetic force, and he discovered that a changing magnetic force field generates an electric current. This discovery paved the way for the invention of the [[electric generator]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[James Clerk Maxwell]] (1831-1879) added another term to Ampère's equation, mathematically developed Faraday's concept of force fields, and summarized the relationship between electricity and magnetism in a set of equations named after him. One of these equations describes how [[Electricity|electric currents]] and changing electric fields produce magnetic fields (the Ampère-Maxwell law), and another equation describes how changing magnetic fields produce electric fields (Faraday's law of induction). In this manner, electricity and magnetism were shown to be linked together. The overall phenomenon came to be called '''electromagnetism''', and the combination of electric and magnetic fields was called the '''electromagnetic field'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Maxwell further showed that [[wave]]s of oscillating electric and magnetic fields travel through empty space at a speed that could be predicted from simple electrical experiments. Using the data available at the time, Maxwell obtained a velocity of 310,740,000 meters per second. Noticing that this figure is nearly equal to the speed of [[light]], Maxwell wrote in 1865 that "it seems we have strong reason to conclude that light itself (including radiant heat, and other radiations if any) is an electromagnetic disturbance in the form of waves propagated through the electromagnetic field according to electromagnetic laws." | ||

| − | + | Nineteenth-century scientists attempted to understand the magnetic field in terms of its effects on a hypothetical medium, called the aether, which also served to propagate electromagnetic waves. The results of later experiments, however, indicated that no such medium exists. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Magnetism of an object == | |

| − | + | The physical cause of the magnetism of an object—as distinct from the production of magnetic fields by electrical currents—is attributed to the "magnetic dipoles" of the atoms in the object. If a wire is bent into a circular loop and current flows through it, it acts as a magnet with one side behaving as a north pole and the other, a south pole. From this observation stemmed the hypothesis that an iron magnet consists of similar currents on the atomic level, produced by the movements of [[electron]]s. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Magnetic dipole moment.png|thumb|right|300px|Bar magnet dipole moment]] | |

| − | + | On the atomic scale, however, the movements of electrons have to be considered on a conceptual, not literal, basis. Literal movements of electrons would require the application of Maxwell's equations, which meet with serious contradictions on the atomic level. To resolve these contradictions, scientists have applied the theory of [[quantum mechanics]], developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. | |

| − | + | According to current theory, the magnetic dipole (or magnetic moment) of an atom is thought to arise from two kinds of quantum-mechanical movements of electrons in the atom. The first is the "orbital motion" of electrons around the nucleus. This motion can be considered a current loop, resulting in what is called an ''orbital dipole magnetic moment'' along an axis that runs through the nucleus. The second, much stronger, source of electronic magnetic moment is due to a quantum-mechanical property called the ''spin dipole magnetic moment'', which is related to the quantum-mechanical "spin" of electrons. | |

| − | + | The overall magnetic moment of an atom is the sum of all the magnetic moments of the individual electrons. For pairs of electrons in an atom, their magnetic moments (both orbital and spin dipole magnetic moments) oppose each other and cancel each other. If the atom has a completely filled [[electron shell]] or subshell, its electrons are all paired up and their magnetic moments completely cancel each other out. Only atoms with partially filled electron shells have a magnetic moment, the strength of which depends on the number of unpaired electrons. | |

| − | + | == Magnetic behavior == | |

| + | A magnetic field contains energy, and physical systems stabilize in a configuration with the lowest energy. Therefore, when a magnetic dipole is placed in a magnetic field, the dipole tends to align itself in a polarity opposite to that of the field, thereby lowering the energy stored in that field. For instance, two identical bar magnets normally line up so that the north end of one is as close as possible to the south end of the other, resulting in no net magnetic field. These magnets resist any attempts to reorient them to point in the same direction. This is why a magnet used as a compass interacts with the Earth's magnetic field to indicate north and south. | ||

| − | + | Depending on the configurations of electrons in their atoms, different substances exhibit differing types of magnetic behavior. Some of the different types of magnetism are: diamagnetism, paramagnetism, ferromagnetism, ferrimagnetism, and antiferromagnetism. | |

| − | + | '''Diamagnetism''' is a form of magnetism exhibited by a substance only in the presence of an externally applied magnetic field. It is thought to result from changes in the orbital motions of electrons when the external magnetic field is applied. Materials that are said to be diamagnetic are those that nonphysicists usually think of as "nonmagnetic," such as [[water]], most organic compounds, and some [[metal]]s (including [[gold]] and [[bismuth]]). | |

| − | + | '''Paramagnetism''' is based on the tendency of atomic magnetic dipoles to align with an external [[magnetic field]]. In a paramagnetic material, the individual atoms have permanent [[dipole moments]] even in the absence of an applied field, which typically implies the presence of an [[unpaired electron]] in the atomic or molecular orbitals. Paramagnetic materials are attracted when subjected to an applied magnetic field. Examples of these materials are aluminum, calcium, magnesium, barium, sodium, platinum, uranium, and liquid oxygen. | |

| − | + | '''Ferromagnetism''' is the "normal" form of magnetism that most people are familiar with, as exhibited by refrigerator magnets and horseshoe magnets. All [[permanent magnet]]s are either ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, as are the [[metal]]s that are noticeably attracted to them. Historically, the term "ferromagnet" was used for any material that could exhibit spontaneous magnetization: a net magnetic moment in the absence of an external [[magnetic field]]. | |

| − | + | More recently, different classes of spontaneous magnetization have been identified, when the material contains more than one magnetic ion per "[[primitive cell]]" (smallest cell of a [[crystal]]line lattice structure). This has led to a stricter definition of ferromagnetism. In particular, a material is said to be "ferromagnetic" only if ''all'' of its magnetic ions add a positive contribution to the net magnetization. If some of the magnetic ions ''subtract'' from the net magnetization (if some are aligned in an "anti" or opposite sense), then the material is said to be '''ferrimagnetic'''. If the ions are completely anti-aligned, so that the net magnetization is zero, despite the presence of magnetic ordering, then the material is said to be an '''antiferromagnet'''. | |

| − | + | All these alignment effects occur only at [[temperature]]s below a certain critical temperature, called the Curie temperature for ferromagnets and ferrimagnets, or the Néel temperature for antiferromagnets. Ferrimagnetism is exhibited by ferrites and magnetic garnets. Antiferromagnetic materials include metals such as [[chromium]], alloys such as iron manganese (FeMn), and oxides such as nickel oxide (NiO). | |

| − | [[ | + | ==Electromagnets== |

| + | As noted above, electricity and magnetism are interlinked. When an [[electricity|electric current]] is passed through a wire, it generates a magnetic field around the wire. If the wire is coiled around an iron bar (or a bar of ferromagnetic material), the bar becomes a temporary magnet called an '''electromagnet'''—it acts as a magnet as long as electricity flows through the wire. Electromagnets are useful in cases where a magnet needs to be switched on and off. For instance, electromagnets are used in large [[crane (machine)|crane]]s that lift and move junked automobiles. | ||

| − | + | ==Permanent magnets== | |

| + | ===Natural metallic magnets=== | ||

| − | + | Some [[metal]]s are ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, and they are found as permanent magnets in their naturally occurring [[ore]]s. These include the ores of [[iron]] ([[magnetite]] or [[lodestone]]), [[cobalt]], and [[nickel]], as well as the rare earth metals [[gadolinium]] and [[dysprosium]] (at a very low temperature). Such naturally occurring magnets were used in the early experiments with magnetism. Technology has expanded the availability of magnetic materials to include various manmade products, all based on naturally magnetic elements. | |

| − | + | ===Composites=== | |

| − | + | ====Ceramic magnets==== | |

| + | Ceramic (or ferrite) magnets are made of a [[sintering|sintered]] [[composite material|composite]] of powdered iron oxide and barium/strontium carbonate (sintering involves heating the powder until the [[particle]]s stick to one another, without melting the material). Given the low cost of the materials and manufacturing methods, inexpensive magnets of various shapes can be easily mass-produced. The resulting magnets are noncorroding but [[brittle]], and they must be treated like other [[ceramic]]s. | ||

| − | + | ====Alnico magnets==== | |

| + | Alnico magnets are made by [[casting]] (melting in a mold) or [[sintering]] a combination of [[aluminum]], nickel, and cobalt with iron and small amounts of other elements added to enhance the properties of the magnet. Sintering offers superior mechanical characteristics, whereas casting delivers higher magnetic fields and allows for the design of intricate shapes. Alnico magnets resist corrosion and have physical properties more forgiving than ferrite, but not quite as desirable as a metal. | ||

| − | + | ====Injection-molded magnets==== | |

| − | + | [[Injection molding|Injection-molded]] magnets are [[composite]]s of various types of [[resin]] and magnetic powders, allowing parts of complex shapes to be manufactured by injection molding. The physical and magnetic properties of the product depend on the raw materials, but they are generally lower in magnetic strength and resemble [[plastic]]s in their physical properties. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Flexible magnets==== | |

| + | Flexible magnets are similar to injection molded magnets, using a flexible resin or binder such as [[vinyl]], and produced in flat strips or sheets. These magnets are lower in magnetic strength but can be very flexible, depending on the binder used. | ||

| − | == | + | ===Rare earth magnets=== |

| + | "Rare earth" ([[Inner transition metal|lanthanoid]]) elements have a partially filled ''f'' [[electron shell]] that can accommodate up to 14 electrons. The spin of these electrons can be aligned, resulting in very strong magnetic fields. These elements are therefore used in compact, high-strength magnets, when their higher price is not a factor. | ||

| − | === | + | ====Samarium cobalt magnets==== |

| − | + | [[Samarium]] [[cobalt]] magnets are highly resistant to oxidation and possess higher magnetic strength and temperature resistance than alnico or ceramic materials. Sintered samarium cobalt magnets are brittle and prone to chipping and cracking and may fracture when subjected to thermal shock. | |

| − | + | ====Neodymium iron boron magnets==== | |

| + | [[Neodymium magnet]]s, more formally referred to as [[neodymium]] [[iron]] [[boron]] (NdFeB) magnets, have the highest magnetic field strength but are inferior to samarium cobalt in resistance to oxidation and temperature. This type of magnet is expensive, due to both the cost of raw materials and licensing of the patents involved. This high cost limits their use to applications where such high strengths from a compact magnet are critical. Use of protective surface treatments—such as [[gold]], [[nickel]], [[zinc]], and [[tin]] plating and [[epoxy]] resin coating—can provide [[corrosion]] protection where required. | ||

| − | === | + | === Single-molecule magnets and single-chain magnets === |

| − | + | In the 1990s, it was discovered that certain molecules containing paramagnetic metal ions are capable of storing a magnetic moment at very low temperatures. These single-molecule magnets (SMMs) are very different from conventional magnets that store information at a "domain" level and the SMMs theoretically could provide a far denser storage medium than conventional magnets. Research on monolayers of SMMs is currently under way. Most SMMs contain manganese, but they can also be found with [[vanadium]], iron, nickel and cobalt clusters. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | More recently, it has been found that some chain systems can display a magnetization that persists for long intervals of time at relatively higher temperatures. These systems have been called single-chain magnets (SCMs). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == Uses of magnets and magnetism == |

| − | + | *Fastening devices: A refrigerator magnet or a magnetic clamp are examples of magnets used to hold things together. Magnetic chucks may be used in [[metalworking]], to hold objects together. | |

| − | + | *Navigation: The [[compass]] has long been used as a handy device that helps travelers find directions. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | *Magnetic recording media: Common [[VHS]] tapes contain a reel of [[magnetic tape]]. The information that makes up the video and sound is encoded on the magnetic coating on the tape. Common [[compact audio cassette|audio cassettes]] also rely on magnetic tape. Similarly, in computers, [[floppy disk]]s and [[hard disk]]s record data on a thin magnetic coating. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[credit card|Credit]], [[debit card|debit]], and [[Automatic Teller Machine|ATM]] cards: Each of these cards has a magnetic strip on one side. This strip contains the necessary information to contact an individual's financial institution and connect with that person's account(s). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *Common [[television]] sets and [[computer]] monitors: Most TV and computer screens rely in part on electromagnets to generate images. [[Plasma screen]]s and [[liquid crystal display|LCD]]s rely on different technologies entirely. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Loudspeaker]]s and [[microphone]]s: A speaker is fundamentally a device that converts electrical energy (the signal) into mechanical energy (the sound), while a microphone does the reverse. They operate by combining the features of a permanent magnet and an electromagnet. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | *[[Electric motor]]s and [[generator]]s: Some electric motors (much like loudspeakers) rely on a combination of an electromagnet and a permanent magnet, as they convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. A generator is the reverse: it converts mechanical energy into electrical energy. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Transformer]]s: Transformers are devices that transfer electrical energy between two windings that are electrically isolated but linked magnetically. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *Maglev trains: With superconducting magnets mounted on the train's underside and in the track, the Maglev train operates on magnetic repulsive forces and "floats" above the track. It can travel at speeds reaching (and sometimes exceeding) 300 miles per hour. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == Force on a charged particle in a magnetic field == |

| − | + | Just as a force is exerted on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field, so a charged particle such as an electron traveling in a magnetic field is deflected due to the force exerted on it. This force is proportional to the velocity of the charge and the magnitude of the magnetic field, but it acts perpedicular to the plane in which they both lie. | |

| − | + | In mathematical terms, if the charged particle moves through a [[magnetic field]] ''B'', it feels a [[force]] ''F'' given by the [[cross product]]: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

:<math>\vec F = q \vec v \times \vec B</math> | :<math>\vec F = q \vec v \times \vec B</math> | ||

| − | where | + | where |

:<math>q\,</math> is the [[electric charge]] of the particle | :<math>q\,</math> is the [[electric charge]] of the particle | ||

:<math>\vec v \,</math> is the [[velocity]] [[vector (spatial)|vector]] of the particle | :<math>\vec v \,</math> is the [[velocity]] [[vector (spatial)|vector]] of the particle | ||

:<math>\vec B \,</math> is the [[magnetic field]] | :<math>\vec B \,</math> is the [[magnetic field]] | ||

| − | Because this is a cross product, the force is [[perpendicular]] to both the motion of the particle and the magnetic field. | + | Because this is a cross product, the force is [[perpendicular]] to both the motion of the particle and the magnetic field. It follows that the magnetic field does no [[mechanical work|work]] on the particle; it may change the direction of the particle's movement, but it cannot cause it to speed up or slow down. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | One tool | + | One tool for determining the directions of the three vectors—the velocity of the charged particle, the magnetic field, and the force felt by the particle—is known as the "right hand rule." The [[index finger]] of the right hand is taken to represent "v"; the [[middle finger]], "B"; and the [[thumb]], "F." When these three fingers are held perpendicular to one another in a gun-like configuration (with the middle finger crossing under the index finger), they indicate the directions of the three vectors that they represent. |

==Units of electromagnetism== | ==Units of electromagnetism== | ||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

===Other magnetism units=== | ===Other magnetism units=== | ||

* [[Gauss (unit)|gauss]]-The '''gauss''', abbreviated as G, is the [[cgs]] [[units of measurement|unit]] of [[magnetic flux density]] or [[magnetic induction]] ('''B'''). | * [[Gauss (unit)|gauss]]-The '''gauss''', abbreviated as G, is the [[cgs]] [[units of measurement|unit]] of [[magnetic flux density]] or [[magnetic induction]] ('''B'''). | ||

| − | * [[oersted]]-The '''oersted''' is the [[ | + | * [[oersted]]-The '''oersted''' is the [[cgs]] [[units of measurement|unit]] of [[magnetic field strength]]. |

| − | * [[maxwell]]-is the unit for | + | * [[maxwell]]-The '''maxwell''' is the unit for [[magnetic flux]]. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [[Electromagnetism]] | * [[Electromagnetism]] | ||

* [[Magnetic field]] | * [[Magnetic field]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [[Michael Faraday]] | * [[Michael Faraday]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[James Clerk Maxwell]] | * [[James Clerk Maxwell]] | ||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | * Griffiths, David J. ''Introduction to Electrodynamics'', 3rd ed. Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 013805326X | ||

| + | * Tipler, Paul. ''Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics'', 5th ed. W. H. Freeman, 2004. ISBN 0716708108 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 5, 2022. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.rare-earth-magnets.com/magnet_university/magnet_university.htm Magnet University] – Resources from the fundamental theory of magnetism to advanced applications of magnetic materials | |

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{magnetic states}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Physics]] | [[Category:Physics]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Electromagnetism]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{credits|Magnetism|63778467|Maxwell's_equations|68575933|Ferromagnetism|68406955|Diamagnetism|68113459|Paramagnetism|69084709|Magnet|69129255}} |

Latest revision as of 05:09, 5 November 2022

In physics, magnetism is one of the phenomena by which materials exert attractive and repulsive forces on other materials. It arises whenever electrically charged particles are in motion—such as the movement of electrons in an electric current passing through a wire.

Some well-known materials that exhibit readily detectable magnetic properties are iron, some steels, and the mineral lodestone (an oxide of iron). Objects with such properties are called magnets, and their ability to attract or repel other materials at a distance has been attributed to a magnetic field. Magnets attract iron and some other metals because they imbue them temporarily with magnetic properties that disappear when the magnets are taken away. All materials are influenced to a greater or lesser extent by a magnetic field.

Every magnet has two poles—or opposite parts—that show uniform force characteristics. The opposite poles of two magnets attract each other, but their similar poles repel each other. No magnet has ever been found to have only one pole. If a magnet is broken, new poles arise at the broken ends so that each new piece has a pair of north and south poles.

The Earth itself is a giant magnet. Its magnetic field shields living organisms by deflecting charged particles coming from the solar wind. In addition, people have taken advantage of this magnetic field for navigational purposes.

With the development of technology, the principles of magnetism have been applied for such purposes as storing information on computer disks, audiotapes, videotapes, and credit/debit cards; displaying images on television and computer screens; converting mechanical energy into electrical energy (as in electricity generators and microphones); and converting electrical energy into mechanical energy (as in electric motors and loudspeakers).

History

The phenomenon of magnetism has been known since ancient times, when it was observed that lodestone, an iron oxide mineral (Fe3O4) with a particular crystalline structure, could attract pieces of iron to itself. The early Chinese and Greeks, among others, found that when a lodestone is suspended horizontally by a string and allowed to rotate around a vertical axis, it orients itself such that one end points approximately toward true north. This end came to be called the north pole (north-seeking pole), while the opposite end was called the south pole (south-seeking pole). In addition, this observation led investigators to infer that the Earth itself is a huge magnet, with a pair of north and south magnetic poles.

The mysteries of magnetic phenomena were documented and clarified by William Gilbert (1544-1603) in his treatise, De Magnete. In the eighteenth century, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736-1806) noted that the forces of attraction or repulsion between two magnetic poles can be calculated by an equation similar to that used to describe the interactions between electric charges. He referred to an "inverse square law," which (in the case of magnets) states that the force of attraction or repulsion between two magnetic poles is directly proportional to the product of the magnitudes of the pole strengths and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the poles.

Connection between magnetism and electricity

It was not until the nineteenth century, however, that investigators began to draw a connection between magnetism and electricity. In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) discovered that a compass, which consists of a small magnet balanced on a central shaft, is deflected in the presence of an electric current. Building on this discovery, Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774-1862) and Félix Savart (1791-1841) established that a current-carrying wire exerts a magnetic force that is inversely proportional to the distance from the wire.

André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) formulated an elegant mathematical expression that defined the link between an electric current and the magnetic force it generates. Michael Faraday (1791-1867) introduced the concept of lines of magnetic force, and he discovered that a changing magnetic force field generates an electric current. This discovery paved the way for the invention of the electric generator.

James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879) added another term to Ampère's equation, mathematically developed Faraday's concept of force fields, and summarized the relationship between electricity and magnetism in a set of equations named after him. One of these equations describes how electric currents and changing electric fields produce magnetic fields (the Ampère-Maxwell law), and another equation describes how changing magnetic fields produce electric fields (Faraday's law of induction). In this manner, electricity and magnetism were shown to be linked together. The overall phenomenon came to be called electromagnetism, and the combination of electric and magnetic fields was called the electromagnetic field.

Maxwell further showed that waves of oscillating electric and magnetic fields travel through empty space at a speed that could be predicted from simple electrical experiments. Using the data available at the time, Maxwell obtained a velocity of 310,740,000 meters per second. Noticing that this figure is nearly equal to the speed of light, Maxwell wrote in 1865 that "it seems we have strong reason to conclude that light itself (including radiant heat, and other radiations if any) is an electromagnetic disturbance in the form of waves propagated through the electromagnetic field according to electromagnetic laws."

Nineteenth-century scientists attempted to understand the magnetic field in terms of its effects on a hypothetical medium, called the aether, which also served to propagate electromagnetic waves. The results of later experiments, however, indicated that no such medium exists.

Magnetism of an object

The physical cause of the magnetism of an object—as distinct from the production of magnetic fields by electrical currents—is attributed to the "magnetic dipoles" of the atoms in the object. If a wire is bent into a circular loop and current flows through it, it acts as a magnet with one side behaving as a north pole and the other, a south pole. From this observation stemmed the hypothesis that an iron magnet consists of similar currents on the atomic level, produced by the movements of electrons.

On the atomic scale, however, the movements of electrons have to be considered on a conceptual, not literal, basis. Literal movements of electrons would require the application of Maxwell's equations, which meet with serious contradictions on the atomic level. To resolve these contradictions, scientists have applied the theory of quantum mechanics, developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

According to current theory, the magnetic dipole (or magnetic moment) of an atom is thought to arise from two kinds of quantum-mechanical movements of electrons in the atom. The first is the "orbital motion" of electrons around the nucleus. This motion can be considered a current loop, resulting in what is called an orbital dipole magnetic moment along an axis that runs through the nucleus. The second, much stronger, source of electronic magnetic moment is due to a quantum-mechanical property called the spin dipole magnetic moment, which is related to the quantum-mechanical "spin" of electrons.

The overall magnetic moment of an atom is the sum of all the magnetic moments of the individual electrons. For pairs of electrons in an atom, their magnetic moments (both orbital and spin dipole magnetic moments) oppose each other and cancel each other. If the atom has a completely filled electron shell or subshell, its electrons are all paired up and their magnetic moments completely cancel each other out. Only atoms with partially filled electron shells have a magnetic moment, the strength of which depends on the number of unpaired electrons.

Magnetic behavior

A magnetic field contains energy, and physical systems stabilize in a configuration with the lowest energy. Therefore, when a magnetic dipole is placed in a magnetic field, the dipole tends to align itself in a polarity opposite to that of the field, thereby lowering the energy stored in that field. For instance, two identical bar magnets normally line up so that the north end of one is as close as possible to the south end of the other, resulting in no net magnetic field. These magnets resist any attempts to reorient them to point in the same direction. This is why a magnet used as a compass interacts with the Earth's magnetic field to indicate north and south.

Depending on the configurations of electrons in their atoms, different substances exhibit differing types of magnetic behavior. Some of the different types of magnetism are: diamagnetism, paramagnetism, ferromagnetism, ferrimagnetism, and antiferromagnetism.

Diamagnetism is a form of magnetism exhibited by a substance only in the presence of an externally applied magnetic field. It is thought to result from changes in the orbital motions of electrons when the external magnetic field is applied. Materials that are said to be diamagnetic are those that nonphysicists usually think of as "nonmagnetic," such as water, most organic compounds, and some metals (including gold and bismuth).

Paramagnetism is based on the tendency of atomic magnetic dipoles to align with an external magnetic field. In a paramagnetic material, the individual atoms have permanent dipole moments even in the absence of an applied field, which typically implies the presence of an unpaired electron in the atomic or molecular orbitals. Paramagnetic materials are attracted when subjected to an applied magnetic field. Examples of these materials are aluminum, calcium, magnesium, barium, sodium, platinum, uranium, and liquid oxygen.

Ferromagnetism is the "normal" form of magnetism that most people are familiar with, as exhibited by refrigerator magnets and horseshoe magnets. All permanent magnets are either ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, as are the metals that are noticeably attracted to them. Historically, the term "ferromagnet" was used for any material that could exhibit spontaneous magnetization: a net magnetic moment in the absence of an external magnetic field.

More recently, different classes of spontaneous magnetization have been identified, when the material contains more than one magnetic ion per "primitive cell" (smallest cell of a crystalline lattice structure). This has led to a stricter definition of ferromagnetism. In particular, a material is said to be "ferromagnetic" only if all of its magnetic ions add a positive contribution to the net magnetization. If some of the magnetic ions subtract from the net magnetization (if some are aligned in an "anti" or opposite sense), then the material is said to be ferrimagnetic. If the ions are completely anti-aligned, so that the net magnetization is zero, despite the presence of magnetic ordering, then the material is said to be an antiferromagnet.

All these alignment effects occur only at temperatures below a certain critical temperature, called the Curie temperature for ferromagnets and ferrimagnets, or the Néel temperature for antiferromagnets. Ferrimagnetism is exhibited by ferrites and magnetic garnets. Antiferromagnetic materials include metals such as chromium, alloys such as iron manganese (FeMn), and oxides such as nickel oxide (NiO).

Electromagnets

As noted above, electricity and magnetism are interlinked. When an electric current is passed through a wire, it generates a magnetic field around the wire. If the wire is coiled around an iron bar (or a bar of ferromagnetic material), the bar becomes a temporary magnet called an electromagnet—it acts as a magnet as long as electricity flows through the wire. Electromagnets are useful in cases where a magnet needs to be switched on and off. For instance, electromagnets are used in large cranes that lift and move junked automobiles.

Permanent magnets

Natural metallic magnets

Some metals are ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, and they are found as permanent magnets in their naturally occurring ores. These include the ores of iron (magnetite or lodestone), cobalt, and nickel, as well as the rare earth metals gadolinium and dysprosium (at a very low temperature). Such naturally occurring magnets were used in the early experiments with magnetism. Technology has expanded the availability of magnetic materials to include various manmade products, all based on naturally magnetic elements.

Composites

Ceramic magnets

Ceramic (or ferrite) magnets are made of a sintered composite of powdered iron oxide and barium/strontium carbonate (sintering involves heating the powder until the particles stick to one another, without melting the material). Given the low cost of the materials and manufacturing methods, inexpensive magnets of various shapes can be easily mass-produced. The resulting magnets are noncorroding but brittle, and they must be treated like other ceramics.

Alnico magnets

Alnico magnets are made by casting (melting in a mold) or sintering a combination of aluminum, nickel, and cobalt with iron and small amounts of other elements added to enhance the properties of the magnet. Sintering offers superior mechanical characteristics, whereas casting delivers higher magnetic fields and allows for the design of intricate shapes. Alnico magnets resist corrosion and have physical properties more forgiving than ferrite, but not quite as desirable as a metal.

Injection-molded magnets

Injection-molded magnets are composites of various types of resin and magnetic powders, allowing parts of complex shapes to be manufactured by injection molding. The physical and magnetic properties of the product depend on the raw materials, but they are generally lower in magnetic strength and resemble plastics in their physical properties.

Flexible magnets

Flexible magnets are similar to injection molded magnets, using a flexible resin or binder such as vinyl, and produced in flat strips or sheets. These magnets are lower in magnetic strength but can be very flexible, depending on the binder used.

Rare earth magnets

"Rare earth" (lanthanoid) elements have a partially filled f electron shell that can accommodate up to 14 electrons. The spin of these electrons can be aligned, resulting in very strong magnetic fields. These elements are therefore used in compact, high-strength magnets, when their higher price is not a factor.

Samarium cobalt magnets

Samarium cobalt magnets are highly resistant to oxidation and possess higher magnetic strength and temperature resistance than alnico or ceramic materials. Sintered samarium cobalt magnets are brittle and prone to chipping and cracking and may fracture when subjected to thermal shock.

Neodymium iron boron magnets

Neodymium magnets, more formally referred to as neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) magnets, have the highest magnetic field strength but are inferior to samarium cobalt in resistance to oxidation and temperature. This type of magnet is expensive, due to both the cost of raw materials and licensing of the patents involved. This high cost limits their use to applications where such high strengths from a compact magnet are critical. Use of protective surface treatments—such as gold, nickel, zinc, and tin plating and epoxy resin coating—can provide corrosion protection where required.

Single-molecule magnets and single-chain magnets

In the 1990s, it was discovered that certain molecules containing paramagnetic metal ions are capable of storing a magnetic moment at very low temperatures. These single-molecule magnets (SMMs) are very different from conventional magnets that store information at a "domain" level and the SMMs theoretically could provide a far denser storage medium than conventional magnets. Research on monolayers of SMMs is currently under way. Most SMMs contain manganese, but they can also be found with vanadium, iron, nickel and cobalt clusters.

More recently, it has been found that some chain systems can display a magnetization that persists for long intervals of time at relatively higher temperatures. These systems have been called single-chain magnets (SCMs).

Uses of magnets and magnetism

- Fastening devices: A refrigerator magnet or a magnetic clamp are examples of magnets used to hold things together. Magnetic chucks may be used in metalworking, to hold objects together.

- Navigation: The compass has long been used as a handy device that helps travelers find directions.

- Magnetic recording media: Common VHS tapes contain a reel of magnetic tape. The information that makes up the video and sound is encoded on the magnetic coating on the tape. Common audio cassettes also rely on magnetic tape. Similarly, in computers, floppy disks and hard disks record data on a thin magnetic coating.

- Credit, debit, and ATM cards: Each of these cards has a magnetic strip on one side. This strip contains the necessary information to contact an individual's financial institution and connect with that person's account(s).

- Common television sets and computer monitors: Most TV and computer screens rely in part on electromagnets to generate images. Plasma screens and LCDs rely on different technologies entirely.

- Loudspeakers and microphones: A speaker is fundamentally a device that converts electrical energy (the signal) into mechanical energy (the sound), while a microphone does the reverse. They operate by combining the features of a permanent magnet and an electromagnet.

- Electric motors and generators: Some electric motors (much like loudspeakers) rely on a combination of an electromagnet and a permanent magnet, as they convert electrical energy into mechanical energy. A generator is the reverse: it converts mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- Transformers: Transformers are devices that transfer electrical energy between two windings that are electrically isolated but linked magnetically.

- Maglev trains: With superconducting magnets mounted on the train's underside and in the track, the Maglev train operates on magnetic repulsive forces and "floats" above the track. It can travel at speeds reaching (and sometimes exceeding) 300 miles per hour.

Force on a charged particle in a magnetic field

Just as a force is exerted on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field, so a charged particle such as an electron traveling in a magnetic field is deflected due to the force exerted on it. This force is proportional to the velocity of the charge and the magnitude of the magnetic field, but it acts perpedicular to the plane in which they both lie.

In mathematical terms, if the charged particle moves through a magnetic field B, it feels a force F given by the cross product:

where

- is the electric charge of the particle

- is the velocity vector of the particle

- is the magnetic field

Because this is a cross product, the force is perpendicular to both the motion of the particle and the magnetic field. It follows that the magnetic field does no work on the particle; it may change the direction of the particle's movement, but it cannot cause it to speed up or slow down.

One tool for determining the directions of the three vectors—the velocity of the charged particle, the magnetic field, and the force felt by the particle—is known as the "right hand rule." The index finger of the right hand is taken to represent "v"; the middle finger, "B"; and the thumb, "F." When these three fingers are held perpendicular to one another in a gun-like configuration (with the middle finger crossing under the index finger), they indicate the directions of the three vectors that they represent.

Units of electromagnetism

SI magnetism units

| Symbol | Name of Quantity | Derived Units | Unit | Base Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Current | ampere (SI base unit) | A | A = W/V = C/s |

| q | Electric charge, Quantity of electricity | coulomb | C | A·s |

| V | Potential difference | volt | V | J/C = kg·m2·s−3·A−1 |

| R, Z, X | Resistance, Impedance, Reactance | ohm | Ω | V/A = kg·m2·s−3·A−2 |

| ρ | Resistivity | ohm metre | Ω·m | kg·m3·s−3·A−2 |

| P | Power, Electrical | watt | W | V·A = kg·m2·s−3 |

| C | Capacitance | farad | F | C/V = kg−1·m−2·A2·s4 |

| Elastance | reciprocal farad | F−1 | V/C = kg·m2·A−2·s−4 | |

| ε | Permittivity | farad per metre | F/m | kg−1·m−3·A2·s4 |

| χe | Electric susceptibility | (dimensionless) | - | - |

| G, Y, B | Conductance, Admittance, Susceptance | siemens | S | Ω−1 = kg−1·m−2·s3·A2 |

| σ | Conductivity | siemens per metre | S/m | kg−1·m−3·s3·A2 |

| H | Auxiliary magnetic field, magnetic field intensity | ampere per metre | A/m | A·m−1 |

| Φm | Magnetic flux | weber | Wb | V·s = kg·m2·s−2·A−1 |

| B | Magnetic field, magnetic flux density, magnetic induction, magnetic field strength | tesla | T | Wb/m2 = kg·s−2·A−1 |

| Reluctance | ampere-turns per weber | A/Wb | kg−1·m−2·s2·A2 | |

| L | Inductance | henry | H | Wb/A = V·s/A = kg·m2·s−2·A−2 |

| μ | Permeability | henry per metre | H/m | kg·m·s−2·A−2 |

| χm | Magnetic susceptibility | (dimensionless) | - | - |

Other magnetism units

- gauss-The gauss, abbreviated as G, is the cgs unit of magnetic flux density or magnetic induction (B).

- oersted-The oersted is the cgs unit of magnetic field strength.

- maxwell-The maxwell is the unit for magnetic flux.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Griffiths, David J. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 3rd ed. Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 013805326X

- Tipler, Paul. Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Electricity, Magnetism, Light, and Elementary Modern Physics, 5th ed. W. H. Freeman, 2004. ISBN 0716708108

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- Magnet University – Resources from the fundamental theory of magnetism to advanced applications of magnetic materials

| Magnetic states |

| diamagnetism – superdiamagnetism – paramagnetism – superparamagnetism – ferromagnetism – antiferromagnetism – ferrimagnetism – metamagnetism – spin glass |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Magnetism history

- Maxwell's_equations history

- Ferromagnetism history

- Diamagnetism history

- Paramagnetism history

- Magnet history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.