Difference between revisions of "Elk" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | {{ | ||

{{Taxobox | {{Taxobox | ||

| color = pink | | color = pink | ||

| Line 24: | Line 23: | ||

| subdivision = | | subdivision = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | The '''elk''' or '''wapiti''' | + | The '''elk''' or '''wapiti''' ''(Cervus canadensis)'' is the second largest [[species]] of [[deer]] in the world, after the [[moose]] ''(Alces alces)'', which is, confusingly, often also called ''elk'' in [[Europe]]. Elk have long, branching antlers and are one of the largest [[mammal]]s in [[North America]] and eastern [[Asia]]. Until recently, elk and [[red deer]] were considered the same species, however [[DNA]] research has indicated that they are different. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | Some cultures revere the elk as a spiritual force. In parts of Asia, antlers and their velvet (a highly vascular [[skin]] that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the growing bone) are used in [[traditional medicine]]s. Elk are hunted as a game species; the meat is leaner and higher in [[protein]] than [[beef]] or [[chicken]] (Robb and Bethge 2001). | + | Some cultures revere the elk as a spiritual force. In parts of [[Asia]], antlers and their velvet (a highly vascular [[skin]] that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the growing bone) are used in [[traditional medicine]]s. Elk are hunted as a game species; the meat is leaner and higher in [[protein]] than [[beef]] or [[chicken]] (Robb and Bethge 2001). |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| Line 33: | Line 32: | ||

In North America, males are called ''bulls'', and females are called ''cows''. In Asia, ''stag'' and ''hind'', respectively, are sometimes used instead. | In North America, males are called ''bulls'', and females are called ''cows''. In Asia, ''stag'' and ''hind'', respectively, are sometimes used instead. | ||

| − | [[Image:RooseveltElk 5061t.JPG| | + | [[Image:RooseveltElk 5061t.JPG|left|thumb|240px|A herd of Roosevelt Elk in Redwood National and State Parks, [[California]].]] |

Elk are more than twice as heavy as [[mule deer]] and have a more reddish hue to their hair coloring, as well as large, buff colored rump patches and smaller tails. [[Moose]] are larger and darker than elk, the bulls have distinctively different antlers, and moose do not herd. | Elk are more than twice as heavy as [[mule deer]] and have a more reddish hue to their hair coloring, as well as large, buff colored rump patches and smaller tails. [[Moose]] are larger and darker than elk, the bulls have distinctively different antlers, and moose do not herd. | ||

| − | Elk cows average 225 kilograms (500 pounds), stand 1.3 meters (4-1/2 feet | + | Elk cows average 225 kilograms (500 pounds), stand 1.3 meters (4-1/2 feet) at the shoulder, and are 2 meters (6-1/2 feet) from nose to tail. Bulls are some 25 percent larger than [[cow]]s at maturity, weighing an average of 315 kilograms (650 pounds), standing 1.5 meters (5 feet) at the shoulder, and averaging 2.4 meters (8 feet) in length (RMEF 2007a). The largest of the subspecies is the Roosevelt elk, found west of the [[Cascade Range]] in the U.S. states of [[California]], [[Oregon]], and [[Washington]], and in the [[Canada|Canadian]] province of [[British Columbia]]. Roosevelt elk have been reintroduced into [[Alaska]], where males have been recorded as weighing up to 590 kilograms (1,300 pounds (Eide 1994). |

| − | Only the males elk have antlers, which start growing in the spring and are shed each winter. The largest antlers may be 1.2 meters (4 feet) long and weigh 18 kilograms (40 pounds) (RMEF 2007b) Antlers are made of [[bone]], which can grow at a rate of 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) per day. While actively growing, the antlers are covered with and protected by a soft layer of highly | + | Only the males elk have antlers, which start growing in the spring and are shed each winter. The largest antlers may be 1.2 meters (4 feet) long and weigh 18 kilograms (40 pounds) (RMEF 2007b) Antlers are made of [[bone]], which can grow at a rate of 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) per day. While actively growing, the antlers are covered with and protected by a soft layer of highly vascularized skin known as velvet. The velvet is shed in the summer when the antlers have fully developed. Bull elk may have six or more tines on each antler, however the number of tines has little to do with the age or maturity of a particular animal. The Siberian and North American elk carry the largest antlers while the Altai wapiti have the smallest (Geist 1998). The formation and retention of antlers is [[testosterone]]-driven (FPLC 1998). After the breeding season in late fall, the level of [[pheromone]]s released during [[estrus]] declines in the environment and the testosterone levels of males drop as a consequence. This drop in testosterone leads to the shedding of antlers, usually in the early winter. |

| + | Elk is a [[ruminant]] species, with a four-chambered stomach, and feeds on plants, [[grass]]es, [[leaf|leaves]], and [[bark]]. During the summer, elk eat almost constantly, consuming between 4.5 and 6.8 kilograms (10 to 15 pounds) daily (RMEF 2007c). As a ruminant species, after food is swallowed, it is kept in the first chamber for a while where it is partly digested with the help of [[microorganism]]s, [[bacteria]], and [[protist]]s. In this [[symbiosis|symbiotic]] relationship, the microorganisms break down the [[cellulose]] in the [[plant]] material into [[carbohydrate]]s, which the ungulate can digest. Both sides receive some benefit from this relationship. The microorganisms get food and a place to live and the ungulate gets help with its digestion. The partly digested food is then sent back up to the mouth where it is chewed again and sent on to the other parts of the stomach to be completely digested. | ||

| − | + | During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Males, females and calves of Siberian and North American elk all grow thick neck manes; female and young [[Manchuria]]n and Alashan wapitis do not (Geist 1993). By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed, and elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies. | |

| − | + | All elk have large and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests (Pisarowicz 2007). Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest adapted Manchurian and Alashan wapitis have darker reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months (Geist 1998). Calves are born spotted, as is common with many [[deer]] species, and they lose their spots by the end of summer. Manchurian wapiti calves may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older (Geist 1998). | |

| − | |||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| − | [[Image:Bull elk bugling during the fall mating season.jpg|right|thumb|Bull elk ''bugling'' during the rut]] | + | [[Image:Bull elk bugling during the fall mating season.jpg|right|thumb|240px|Bull elk ''bugling'' during the rut]] |

| − | Modern subspecies are descended from elk that once inhabited [[Beringia]], a [[steppe]] region between Asia and North America that connected the two continents during the [[Pleistocene]]. Beringia provided a migratory route for numerous mammal species, including [[brown bear]], [[caribou]], and moose, as well as humans | + | Modern subspecies are considered to have descended from elk that once inhabited [[Beringia]], a [[steppe]] region between [[Asia]] and [[North America]] that connected the two continents during the [[Pleistocene]]. Beringia provided a migratory route for numerous mammal species, including [[brown bear]], [[caribou]], and [[moose]], as well as humans (Flannery 2001). As the Pleistocene came to an end, ocean levels began to rise; elk migrated southwards into Asia and North America. In North America, they adapted to almost all [[ecosystem]]s except for [[tundra]], true deserts, and the gulf coast of what is now the U.S. The elk of southern [[Siberia]] and central Asia were once more widespread but today are restricted to the mountain ranges west of [[Lake Baikal]] including the [[Sayan Mountains|Sayan]] and [[Altai Mountains]] of [[Mongolia]] and the [[Tian Shan|Tianshan]] region that borders [[Kyrgyzstan]], [[Kazakhstan]], and China's [[Xinjiang]] Province (IUCN 2007). The habitat of Siberian elk in Asia is similar to that of the [[Rocky Mountains|Rocky Mountain]] subspecies in North America. |

| − | Throughout their range, they live in [[forest]] and in forest edge habitat, similar to other deer species. In [[mountain]]ous regions, they often dwell at higher elevations in summer, migrating down slope for winter. The highly adaptable elk also inhabit semi-deserts in North America, such as the [[Great Basin]]. | + | Throughout their range, they live in [[forest]] and in forest edge habitat, similar to other deer species. In [[mountain]]ous regions, they often dwell at higher elevations in summer, migrating down slope for winter. The highly adaptable elk also inhabit semi-deserts in North America, such as the [[Great Basin]]. [[Manchuria]]n and Alashan wapiti are primarily forest dwellers and their smaller antler sizes is a likely adaptation to a forest environment. |

===Introductions=== | ===Introductions=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Wapiti.Nebraska.JPG|right|thumb|Bull elk on a captive range in [[Nebraska]]. These elk, originally from Rocky Mountain herds, exhibit modified behavior due to having been held in captivity | + | [[Image:Wapiti.Nebraska.JPG|right|thumb|240px|Bull elk on a captive range in [[Nebraska]]. These elk, originally from Rocky Mountain herds, exhibit modified behavior due to having been held in captivity.]] |

| − | The Rocky Mountain elk subspecies has been reintroduced by hunter-conservation organizations in the [[Appalachia]]n region of the eastern | + | The Rocky Mountain elk subspecies has been reintroduced by hunter-conservation organizations in the [[Appalachia]]n region of the eastern United States, where the now extinct Eastern elk once lived (Fitzgerald 2007). After elk were reintroduced in the states of [[Kentucky]], [[North Carolina]], and [[Tennessee]], they migrated into the neighboring states of [[Virginia]] and [[West Virginia]], and have established permanent populations there (Ledford 2005). Elk have also been reintroduced to a number of other states, including [[Pennsylvania]], [[Michigan]], and [[Wisconsin]]. As of 1989, population figures for the Rocky Mountain subspecies were 782,500, and estimated numbers for all North American subspecies exceeded 1 million (Peek 2007). Prior to the European colonization of North America, there were an estimated 10 million elk on the continent (RMEF 2007a). |

| + | |||

| + | Worldwide population of elk, counting those on farms and in the wild, is approximately 2 million. | ||

| − | Outside their native habitat, elk and other deer species were introduced in areas that previously had few if any large native | + | Outside their native habitat, elk and other deer species were introduced in areas that previously had few if any large native [[ungulate]]s. Brought to these countries for hunting and ranching for meat, hides, and antler velvet, they have proven highly adaptable and have often had an adverse impact on local [[ecosystem]]s. Elk and red deer were introduced to [[Argentina]] and [[Chile]] in the early twentieth century. There they are now considered an [[invasive species]], encroaching on Argentinian ecosystems where they compete for food with the indigenous [[Chilean Huemul]] and other herbivores (Galende et al. 2005). This negative impact on native animal species has led the [[International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources|IUCN]] to identify the elk as one of the world's 100 worst invaders (Flueck 2007). Both elk and red deer have also been introduced to [[Ireland]] and [[Australia]] (Corbet and Harris 1996). |

| − | The introduction of deer to [[New Zealand]] began in the middle of the | + | The introduction of deer to [[New Zealand]] began in the middle of the nineteenth century, and current populations are primarily European red deer, with only 15 percent being elk (DF 2003). These deer have had an adverse impact on forest regeneration of some plant species, as they consume more palatable species, which are replaced with those that are less favored by the elk. The long term impact will be an alteration of the types of plants and trees found, and in other animal and plant species dependent upon them (Husheer 2007). As in [[Chile]] and Argentina, the IUCN has declared that red deer and elk populations in New Zealand are an invasive species (Flueck 2007). |

==Behavior== | ==Behavior== | ||

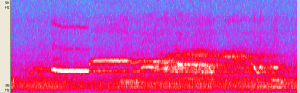

| − | [[Image:American Elk bugling spectrogram.png|thumb|American elk bugling spectrogram,<br>— '''[[Media:American Elk Bugling.ogg|Play audio (OGG format, 25kB)]]''',<br>— | + | [[Image:American Elk bugling spectrogram.png|thumb|American elk bugling spectrogram,<br/>—'''[[Media:American Elk Bugling.ogg|Play audio (OGG format, 25kB)]]''',<br/>— |

'''[http://www.nps.gov/archive/wica/Sounds/Elk_Bugling.wav Play audio (wav format)]'''.]] | '''[http://www.nps.gov/archive/wica/Sounds/Elk_Bugling.wav Play audio (wav format)]'''.]] | ||

| − | Adult elk usually stay in single-sex groups for most of the year. During the mating period known as the | + | Adult elk usually stay in single-sex groups for most of the year. During the mating period known as the rut, mature bulls compete for the attentions of the cows and will try to defend females in their harem. Rival bulls challenge opponents by bellowing and by paralleling each other, walking back and forth. This allows potential combatants to assess the others' antlers, body size, and fighting prowess. If neither bull backs down, they engage in antler wrestling, and bulls sometimes sustain serious injuries. Bulls also dig holes in the ground, in which they urinate and roll their body. The urine soaks into their hair and gives them a distinct smell that attracts cows (Walker 2007). |

| + | |||

| + | Dominant bulls follow groups of cows during the rut, from August into early winter. A bull will defend his harem of 20 cows or more from competing bulls and predators (SDDGFP 2007). Only mature bulls have large harems and breeding success peaks at about eight years of age. Bulls between two to four years and over 11 years of age rarely have harems and spend most of the rut on the periphery of larger harems. Young and old bulls that do acquire a harem hold it later in the breeding season than do bulls in their prime. A bull with a harem rarely feeds and he may lose up to 20 percent of his body weight. Bulls that enter the rut in poor condition are less likely to make it through to the peak conception period or have the strength to survive the rigors of the oncoming winter (Walker 2007). | ||

| − | + | Bulls have a loud vocalization consisting of screams known as ''bugling'', which can be heard for miles. Bugling is often associated with an adaptation to open environments such as parklands, meadows, and savannas, where sound can travel great distances. Females are attracted to the males that bugle more often and have the loudest call (Thomas and Toweill 2002). Bugling is most common early and late in the day and is one of the most distinctive sounds in nature, akin to the howl of the [[gray wolf]]. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Wapiti (01) 2006-09-19.JPG|right|thumb|240px|Female nursing young.]] | |

| + | Female elk have a short [[estrus]] cycle of only a day or two and matings usually involve a dozen or more attempts. By the fall of their second year, females can produce one and, very rarely, two offspring, though reproduction is most common when cows weigh at least 200 kilograms (450 pounds) (Sell 2007). The [[gestation]] period is 240 to 262 days and the offspring weigh between 15 and 16 kilograms (33 to 35 pounds). When the females are near to giving birth, they tend to isolate themselves from the main herd, and will remain isolated until the calf is large enough to escape predators (WDFW 2007). | ||

| − | + | Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and they lose their spots by the end of summer. Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. After two weeks, calves are able to join the herd and are fully weaned at two months of age (MMMZ 2007). Elk calves weigh as much as an adult [[white-tailed deer]] by the time they are six months old (WERP 2007). The offspring will remain with their mothers for almost a year, leaving about the time that the next season's offspring are produced (Thomas and Toweill 2002). The gestation period is the same for all subspecies. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Elk live 20 years or more in captivity but average 10 to 13 years in the wild. In some subspecies that suffer less predation, they may live an average of 15 years in the wild. | + | Elk live 20 years or more in captivity but average 10 to 13 years in the wild. In some subspecies that suffer less predation, they may live an average of 15 years in the wild (NPS 2007). |

===Protection from predators=== | ===Protection from predators=== | ||

| − | Male elk retain their antlers for more than half the year and are less likely to group with other males when they have antlers. Antlers provide a means of defense, as does a strong front-leg kick, which is performed by either sex if provoked. Once the antlers have been shed, bulls tend to form bachelor groups which allow them to work cooperatively at fending off predators. Herds tend to employ one or more scouts while the remaining members eat and rest. | + | Male elk retain their antlers for more than half the year and are less likely to group with other males when they have antlers. Antlers provide a means of defense, as does a strong front-leg kick, which is performed by either sex if provoked. Once the antlers have been shed, bulls tend to form bachelor groups which allow them to work cooperatively at fending off predators. Herds tend to employ one or more scouts while the remaining members eat and rest (Thomas and Toweill 2002). |

| − | After the rut, females form large herds of up to 50 individuals. Newborn calves are kept close by a series of vocalizations; larger nurseries have an ongoing and constant chatter during the daytime hours. When approached by predators, the largest and most robust females may make a stand, using their front legs to kick at their attackers. Guttural grunts and posturing are used with great effectiveness with all but the most determined of predators. Aside from man, wolf and [[coyote]] packs and the solitary [[cougar]] | + | After the rut, females form large herds of up to 50 individuals. Newborn calves are kept close by a series of vocalizations; larger nurseries have an ongoing and constant chatter during the daytime hours. When approached by predators, the largest and most robust females may make a stand, using their front legs to kick at their attackers. Guttural grunts and posturing are used with great effectiveness with all but the most determined of predators. Aside from man, wolf and [[coyote]] packs and the solitary [[cougar]] are the most likely predators, although [[Brown Bear|brown]], [[Grizzly Bear|grizzly]], and [[American black bear|black bears]] also prey on elk (Thomas and Toweill 2002). In the [[Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem]], which includes [[Yellowstone National Park]], bears are the most significant predators of calves (Barber et al. 2005). Major predators in Asia include the [[wolf]], [[dhole]], brown [[bear]], [[siberian tiger]], [[Amur leopard]], and [[snow leopard]]. [[Eurasian lynx]] and wild [[boar]] sometimes prey on the Asian wapiti (Geist 1998). |

===Migration=== | ===Migration=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Wapiti on the National Elk Refuge.jpg|right|thumb|Elk wintering in | + | [[Image:Wapiti on the National Elk Refuge.jpg|right|thumb|240px|Elk wintering in Jackson Hole, [[Wyoming]] after migrating there during the fall]] |

| − | The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem elk herd numbers over 200,000 individuals and during the spring and fall, they take part in the longest elk | + | The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem elk herd numbers over 200,000 individuals and, during the spring and fall, they take part in the longest elk migration in the continental U.S. Elk in the southern regions of [[Yellowstone National Park]] and in the surrounding National Forests migrate south towards the town of [[Jackson, Wyoming]] where they winter for up to six months on the [[National Elk Refuge]]. [[Conservation]]ists there ensure the herd is well fed during the harsh winters (USFWS 2007). Many of the elk that reside in the northern sections of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem migrate to lower altitudes in [[Montana]], mainly to the north and west. |

| − | As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk migrate into areas of higher altitude in the spring, following the retreating snows, and the opposite direction in the fall. Hunting pressure also impacts migration and movements | + | As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk migrate into areas of higher altitude in the spring, following the retreating snows, and the opposite direction in the fall. Hunting pressure also impacts migration and movements (Jenkins 2001). During the winter, they favor wooded areas and sheltered valleys for protection from the wind and availability of tree bark to eat. Roosevelt elk are generally non-migratory due to less seasonal variability of food sources (Thomas and Toweill 2002). |

==Health issues== | ==Health issues== | ||

| − | Brainworm | + | Brainworm ''([[Parelaphostrongylus tenuis]])'' is a [[parasite|parasitic]] [[nematode]] that has been known to affect the spinal cord and brain tissue of elk, leading to death. The nematode has a carrier in the white-tailed deer in which it normally has no ill effects. Nonetheless, it is carried by [[snail]]s, which can be inadvertently consumed by elk during grazing (Fergus 2007). |

| − | it is carried by | ||

| − | [[Chronic Wasting Disease]] affects the brain tissue in elk | + | [[Chronic Wasting Disease]] affects the brain tissue in elk and has been detected throughout their range in North America. First documented in the late 1960s in mule deer, the disease has affected elk on game farms and in the wild in a number of regions. Elk that have contracted the disease begin to show weight loss, increased watering needs, disorientation and listlessness, and at an advanced stage the disease leads to death. The disease is similar to but not the same as [[Mad Cow Disease]], and no dangers to humans have been documented, nor has the disease been demonstrated to pose a threat to domesticated cattle (RMEF 2007d). In 2002, [[South Korea]] banned the importation of elk antler velvet due to concerns about chronic wasting disease (Hansen 2006). |

| − | [[Brucellosis]] occasionally affect elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the only place in the U.S. where the disease is still known to exist. In domesticated cattle, brucellosis causes infertility, abortions and reduced milk production. It is transmitted to humans as [[undulant fever]], producing [[influenza|flu]]-like symptoms | + | [[Brucellosis]] occasionally affect elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the only place in the U.S. where the disease is still known to exist. In domesticated cattle, brucellosis causes infertility, abortions, and reduced milk production. It is transmitted to humans as [[undulant fever]], producing [[influenza|flu]]-like symptoms that may last for years. Though [[bison]] are more likely to transmit the disease to other animals, elk inadvertently transmitted brucellosis to horses in Wyoming and cattle in [[Idaho]]. Researchers are attempting to eradicate the disease through vaccinations and herd management measures, which are expected to be successful (USDA 2007). |

| + | ==Naming and etymology== | ||

| + | While the term "elk" refers to ''Cervus canadensis'' in North America, the term elk refers to ''Alces alces'' in English-speaking Europe, a deer that is known as "moose" in North America. The American Indian "waapiti," meaning "white rump" and used by the Shawnees for this animal, has come to be a word, as "wapiti," that can more clearly distinguish ''Cervus canadensis''. | ||

| + | Early European explorers to North America, who were familiar with the smaller red deer of Europe, believed that the much larger North American animal looked more like a moose, hence they used the common European name for the moose. The name ''elk'' is from the [[German Language|German]] word for moose, which is ''elch'' (PEH 2007). | ||

| − | + | The elk is also referred to as the ''maral'' in Asia, though this is due to confusion with the [[central Asian red deer]], which is a very similar species. | |

| − | |||

==Taxonomy== | ==Taxonomy== | ||

===Subspecies=== | ===Subspecies=== | ||

| − | ''[[Cervus]]'' [[genus]] | + | Elk ancestors of the ''[[Cervus]]'' [[genus]] first appear in the [[fossil]] record 12 million years ago, during the [[Pliocene]] in [[Eurasia]], but they do not appear in the North American fossil record until the later [[Pleistocene]] [[ice age]]s, when they apparently crossed the [[Bering land bridge]] (USGS 2006). The extinct [[Irish Elk]] ''(Megaloceros)'' was not a member of the genus ''Cervus'', but rather the largest member of the wider deer family ([[Cervidae]]) known from the fossil record (Gould 1977). |

| + | |||

| + | There are numerous [[subspecies]] of elk. Some recognize six subspecies from North America in recent historical times and five from Asia, although some [[Taxonomy|taxonomists]] consider them different [[ecotype]]s or [[race]]s of the same species (adapted to local environments through minor changes in appearance and behavior). Populations vary as to antler shape and size, body size, coloration and mating behavior. [[DNA]] investigations of the Eurasian subspecies revealed that [[Phenotype|phenotypic]] variation in antlers, mane and rump patch development are based on "climatic-related lifestyle factors" (Groves 2005). | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:Audobon-eastern-elk.jpg|thumb|right|[[John James Audubon|Audubon]]'s "''Eastern Elk''" which is now extinct]] | [[Image:Audobon-eastern-elk.jpg|thumb|right|[[John James Audubon|Audubon]]'s "''Eastern Elk''" which is now extinct]] | ||

| − | Of the six subspecies of elk | + | Of the six subspecies of elk considered to have inhabited North America in recent times, four remain, including the Roosevelt ''(C. canadensis roosevelti)'', Tule ''(C. canadensis nannodes)'', Manitoban ''(C. canadensis manitobensis)'', and Rocky Mountain ''(C. canadensis nelsoni)'' (Keck 2007). The Eastern elk ''(C. canadensis canadensis)'' and Merriam's elk ''(C. canadensis merriami)'' subspecies have been extinct for at least a century (Gerhart 2007; Allen 2007). Classification of the four surviving North American groups as subspecies is maintained, at least partly, for political purposes to permit individualized conservation and protective measures for each of the surviving populations (Geist 1993). |

| + | |||

| + | Five subspecies found in Asia include the Altai ''(C. canadensis sibiricus)'', the Tianshan ''(C. canadensis songaricus)'', and the Asian wapitis ''(C. canadensis asiaticus)'', also known as the Siberian elk. Two distinctive subspecies found in [[China]] and [[Korea]] are the Manchurian ''(C. canadensis xanthopygus)'' and the Alashan wapitis ''(C. canadensis alashanicus)''. The Manchurian wapiti is darker and more reddish in coloration than the other populations. The Alashan wapiti of north central China is the smallest of all subspecies, has the lightest coloration and is the least studied (Geist 1998). | ||

| − | + | [[Valerius Geist]], who has written on the world's various deer species, holds that there are only three subspecies of elk. Geist maintains the Manchurian and Alashan wapiti but places all other elk into ''C. canadensis canadensis'' (Geist 1993). | |

===DNA research=== | ===DNA research=== | ||

| − | Until 2004, red deer and elk were considered to be one species, ''Cervus elaphus'', based on fertile hybrids that have been produced in captivity. Recent DNA studies, conducted on hundreds of samples from red deer and elk subspecies as well as other species of the ''Cervus'' deer family, showed that there are three distinct species, dividing them into the east Asian and North American elk (wapiti) | + | Until 2004, red deer and elk were considered to be one species, ''Cervus elaphus'', based on fertile hybrids that have been produced in captivity. Recent DNA studies, conducted on hundreds of samples from red deer and elk subspecies as well as other species of the ''Cervus'' deer family, showed that there are three distinct species, dividing them into the east Asian and North American elk (wapiti) ''(C. canadensis)'', the central Asian red deer ''(C. affinis)'', and the European red deer ''(C. elaphus)'' (Ludt et al. 2004). |

| − | |||

| − | The previous classification had over a dozen subspecies under the ''C. elaphus'' species designation; DNA evidence concludes that elk are more closely related to central Asian red deer and even [[sika deer]] than they are to the red deer. | + | The previous classification had over a dozen subspecies under the ''C. elaphus'' species designation; DNA evidence concludes that elk are more closely related to central Asian red deer and even [[sika deer]] than they are to the red deer (Ludt et al. 2004). Though elk and red deer can produce fertile offspring in captivity, geographic isolation between the species in the wild and differences in mating behaviors indicate that reproduction between them outside a controlled environment would be unlikely (Geist 1998). |

| + | ==Cultural references== | ||

| + | Elk have played an important role in the cultural history of a number of peoples. | ||

| − | + | [[Pictogram]]s and [[petroglyph]]s of elk were carved into cliffs thousands of years ago by the [[Ancient Pueblo Peoples|Anasazi]] of the southwestern United States. More recent Native American tribes, including the [[Kootenai (tribe)|Kootenai]], [[Cree]], [[Ojibwa]], and [[Pawnee]], produced blankets and robes from elk hides. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | The elk was of particular importance to the [[Lakota people|Lakota]] and played a spiritual role in their society (RMEF 2007e). At birth, Lakota males were given an elk's tooth to promote a long life since that was seen as the last part of dead elk to rot away. The elk was seen as having strong sexual potency and young Lakota males who had dreamed of elk would have an image of the mythical representation of the elk on their "courting coats" as a sign of sexual prowess. The Lakota believed that the mythical or spiritual elk, not the physical one, was the teacher of men and the embodiment of strength, sexual prowess, and courage (Halder 2002). | ||

| − | [[Neolithic]] petroglyphs from Asia depict antler-less female elk, which have been interpreted as symbolizing rebirth and sustenance. By the beginning of the [[Bronze Age]], the elk is depicted less frequently in rock art, coinciding with a cultural transformation away from hunting | + | [[Neolithic]] petroglyphs from Asia depict antler-less female elk, which have been interpreted as symbolizing rebirth and sustenance. By the beginning of the [[Bronze Age]], the elk is depicted less frequently in rock art, coinciding with a cultural transformation away from hunting (Jacobson 1993). |

==Commercial uses== | ==Commercial uses== | ||

| − | [[Image:Elk Stags.jpg|right|thumb|Bull elk in spring are shedding their winter coats, and their antlers are covered in velvet]] | + | [[Image:Elk Stags.jpg|right|thumb|240px|Bull elk in spring are shedding their winter coats, and their antlers are covered in velvet]] |

| − | Elk are held in captivity for a variety of reasons. [[Hunting]] interests set aside game farms, where hunters can pay a fee and | + | Elks have traditionally been hunted for food, sport, and their hides. For thousands of years, elk hides have been used for [[tepee]] covering, blankets, clothing, and footwear. Modern uses are more decorative, but elk skin shoes, gloves, and belts are sometimes produced. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Elk are held in captivity for a variety of reasons. [[Hunting]] interests set aside game farms, where hunters can pay a fee and have a greatly increased chance to shoot an elk, as they are fenced in and have less opportunity to escape. They are not generally harvested for meat production on a large scale; however, some restaurants offer the meat as a specialty item and it is also available in some grocery stores. | |

| − | Elk | + | Elk meat has a taste somewhere between [[beef]] and [[venison]] and is higher in [[protein]] and lower in [[fat]] than either beef or [[chicken]] (Wapiti.net 2007). Elk meat is also a good source of [[iron]], [[phosphorus]], and [[zinc]], but is high in [[cholesterol]] (ND 2007). |

| − | + | A male elk can produce 10 to 11 kilograms (22 to 25 pounds) of antler velvet annually. On ranches in the United States, [[Canada]], and [[New Zealand]], this velvet is collected and sold to markets in east Asia, where it is used in medicine. Velvet is also considered by some cultures to be an [[aphrodisiac]]. | |

| − | + | Antlers also are used in artwork, furniture, and other novelty items. All Asian subspecies, along with other deer, have been raised for their antlers in central and eastern Asia by [[Han Chinese]], [[Turkic peoples]], [[Tungusic peoples]], [[Mongolians]], and [[Koreans]]. Elk farms are relatively common in North America and New Zealand. | |

| − | + | Since 1967, the [[Boy Scouts of America]] have assisted employees at the National Elk Refuge in [[Wyoming]] by collecting the antlers that are shed each winter. The antlers are then auctioned with most of the proceeds returned to the refuge. In 2006, 3,200 kilograms (7,060 pounds) of antlers were auctioned, bringing in almost USD$76,000. Another 980 kilograms (2,160 pounds) were sold directly for local use, restoring some decorative arches in the Jackson Town Square (USFWS 2006). | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Allen, C. [http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/SNT/noframe/sw159.htm Elk reintroductions]. ''U.S. Geological Survey''(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | |

| + | |||

| + | * Corbet, G. B., and S. Harris. ''The Handbook of British Mammals''. Blackwell Science, 1996. ISBN 978-0865427112. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Eide, S. [http://www.adfg.state.ak.us/pubs/notebook/biggame/elk.php Roosevelt elk]. ''Alaska Department of Fish and Game''(1994). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Fergus, C. [http://www.pgc.state.pa.us/pgc/cwp/view.asp?a=458&q=150769 Elk]. ''Pennsylvania Game Commission'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Flannery, T. ''The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and Its Peoples''. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001. ISBN 0871137895. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Flueck, W. [http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=119&fr=1&sts=sss ''Cervus elaphus'' (mammal)]. ''Global Invasive Species Database, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Galende, G., E. Ramilo, and A. Beati. [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tandf/snfe/2005/00000040/00000001/art00001 Diet of Huemul deer ''(Hippocamelus bisulcus)'' in Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina]. ''Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment'' 40(1): 1-5. 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Geist, V. ''Elk Country''. Minneapolis: Northword Press, 1993. ISBN 978-1559712088. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Geist, V. ''Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behavior, and Ecology''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0811704960. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Gould, S. J. [http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mammal/artio/irishelk.html The misnamed, mistreated, and misunderstood Irish elk]. 79–90 in ''Ever Since Darwin''. W.W. Norton, New York, 1977. ISBN 0393009173. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Husheer, S. W. [http://www.nzes.org.nz/nzje/new_issues/NZJEcol_HusheerIP.pdf Introduced red deer reduce tree regeneration in Pureora Forest, central North Island, New Zealand]. ''New Zealand Journal of Ecology'' 31(1). (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | * Jacobson, E. ''The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia: A Study in the Ecology of Belief''. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 1993. ISBN 978-9004096288. | ||

| − | + | * Keck, S. [http://www.bowhunting.net/NAspecies/elk1.html#subspecies Elk ''(Cervus canadensis)''. ''Bowhunting.net'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | |

| − | + | * National Park Service (NPS). 2007. [http://www.nps.gov/grsm/naturescience/elk.htm Elk]. ''Great Smoky Mountains''. Retrieved December 31, 2021. | |

| + | * Peek, J. M. [http://biology.usgs.gov/s+t/noframe/c273.htm North American elk]. ''U.S. Geological Survey''(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| − | + | * Robb, B, and G. Bethge. ''The Ultimate Guide to Elk Hunting''. The Lyons Press, 2001. ISBN 1585741809. | |

| + | * Sell, R. [http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/alt-ag/elk.htm Elk]. ''North Dakota State University, Alternative Agriculture Series''(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021 | ||

| − | + | * Thomas, J. W., and D. Toweill. ''Elk of North America, Ecology and Management''. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 158834018X. | |

| + | |||

| + | * United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services. [http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/nahps/brucellosis/cattle.htm#About%20Elk Brucellosis and Yellowstone Bison]. ''Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services, USDA'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| − | + | * United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). [http://www.fws.gov/nationalelkrefuge National Elk Refuge]. ''U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | |

| − | *[http://www. | + | |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * United States Geological Survey (USGS). [http://esp.cr.usgs.gov/research/alaska/alaskaC.html Ecosystem and climate history of Alaska]. ''U.S. Geological Survey'' (2006). Retrieved December 31, 2021. |

| − | [ | + | |

| + | * University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology (UMMZ). [http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Cervus_elaphus.html ''Cervus elaphus'']. ''Animal Diversity Web''(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Walker, M. [http://www.worlddeer.org/reddeer.html The red deer]. ''World Deer Website'' (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Wapiti.net. [http://www.wapiti.net/nutrition.cfm Elk meat nutritional information]. ''Wapiti.net''(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{credit|145083592}} | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Animals]] | |

| + | [[Category:Mammals]][[Category:Ungulates]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:44, 31 December 2021

| Cervus canadensis | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Cervus canadensis (Erxleben, 1777)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

Range of Cervus canadensis

|

The elk or wapiti (Cervus canadensis) is the second largest species of deer in the world, after the moose (Alces alces), which is, confusingly, often also called elk in Europe. Elk have long, branching antlers and are one of the largest mammals in North America and eastern Asia. Until recently, elk and red deer were considered the same species, however DNA research has indicated that they are different.

Some cultures revere the elk as a spiritual force. In parts of Asia, antlers and their velvet (a highly vascular skin that supplies oxygen and nutrients to the growing bone) are used in traditional medicines. Elk are hunted as a game species; the meat is leaner and higher in protein than beef or chicken (Robb and Bethge 2001).

Description

The elk is a large ungulate animal of the Artiodactyla order (even-toed ungulates), possessing an even number of toes on each foot, similar to those of camels, goats, and cattle.

In North America, males are called bulls, and females are called cows. In Asia, stag and hind, respectively, are sometimes used instead.

Elk are more than twice as heavy as mule deer and have a more reddish hue to their hair coloring, as well as large, buff colored rump patches and smaller tails. Moose are larger and darker than elk, the bulls have distinctively different antlers, and moose do not herd.

Elk cows average 225 kilograms (500 pounds), stand 1.3 meters (4-1/2 feet) at the shoulder, and are 2 meters (6-1/2 feet) from nose to tail. Bulls are some 25 percent larger than cows at maturity, weighing an average of 315 kilograms (650 pounds), standing 1.5 meters (5 feet) at the shoulder, and averaging 2.4 meters (8 feet) in length (RMEF 2007a). The largest of the subspecies is the Roosevelt elk, found west of the Cascade Range in the U.S. states of California, Oregon, and Washington, and in the Canadian province of British Columbia. Roosevelt elk have been reintroduced into Alaska, where males have been recorded as weighing up to 590 kilograms (1,300 pounds (Eide 1994).

Only the males elk have antlers, which start growing in the spring and are shed each winter. The largest antlers may be 1.2 meters (4 feet) long and weigh 18 kilograms (40 pounds) (RMEF 2007b) Antlers are made of bone, which can grow at a rate of 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) per day. While actively growing, the antlers are covered with and protected by a soft layer of highly vascularized skin known as velvet. The velvet is shed in the summer when the antlers have fully developed. Bull elk may have six or more tines on each antler, however the number of tines has little to do with the age or maturity of a particular animal. The Siberian and North American elk carry the largest antlers while the Altai wapiti have the smallest (Geist 1998). The formation and retention of antlers is testosterone-driven (FPLC 1998). After the breeding season in late fall, the level of pheromones released during estrus declines in the environment and the testosterone levels of males drop as a consequence. This drop in testosterone leads to the shedding of antlers, usually in the early winter.

Elk is a ruminant species, with a four-chambered stomach, and feeds on plants, grasses, leaves, and bark. During the summer, elk eat almost constantly, consuming between 4.5 and 6.8 kilograms (10 to 15 pounds) daily (RMEF 2007c). As a ruminant species, after food is swallowed, it is kept in the first chamber for a while where it is partly digested with the help of microorganisms, bacteria, and protists. In this symbiotic relationship, the microorganisms break down the cellulose in the plant material into carbohydrates, which the ungulate can digest. Both sides receive some benefit from this relationship. The microorganisms get food and a place to live and the ungulate gets help with its digestion. The partly digested food is then sent back up to the mouth where it is chewed again and sent on to the other parts of the stomach to be completely digested.

During the fall, elk grow a thicker coat of hair, which helps to insulate them during the winter. Males, females and calves of Siberian and North American elk all grow thick neck manes; female and young Manchurian and Alashan wapitis do not (Geist 1993). By early summer, the heavy winter coat has been shed, and elk are known to rub against trees and other objects to help remove hair from their bodies.

All elk have large and clearly defined rump patches with short tails. They have different coloration based on the seasons and types of habitats, with gray or lighter coloration prevalent in the winter and a more reddish, darker coat in the summer. Subspecies living in arid climates tend to have lighter colored coats than do those living in forests (Pisarowicz 2007). Most have lighter yellow-brown to orange-brown coats in contrast to dark brown hair on the head, neck, and legs during the summer. Forest adapted Manchurian and Alashan wapitis have darker reddish-brown coats with less contrast between the body coat and the rest of the body during the summer months (Geist 1998). Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and they lose their spots by the end of summer. Manchurian wapiti calves may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older (Geist 1998).

Distribution

Modern subspecies are considered to have descended from elk that once inhabited Beringia, a steppe region between Asia and North America that connected the two continents during the Pleistocene. Beringia provided a migratory route for numerous mammal species, including brown bear, caribou, and moose, as well as humans (Flannery 2001). As the Pleistocene came to an end, ocean levels began to rise; elk migrated southwards into Asia and North America. In North America, they adapted to almost all ecosystems except for tundra, true deserts, and the gulf coast of what is now the U.S. The elk of southern Siberia and central Asia were once more widespread but today are restricted to the mountain ranges west of Lake Baikal including the Sayan and Altai Mountains of Mongolia and the Tianshan region that borders Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and China's Xinjiang Province (IUCN 2007). The habitat of Siberian elk in Asia is similar to that of the Rocky Mountain subspecies in North America.

Throughout their range, they live in forest and in forest edge habitat, similar to other deer species. In mountainous regions, they often dwell at higher elevations in summer, migrating down slope for winter. The highly adaptable elk also inhabit semi-deserts in North America, such as the Great Basin. Manchurian and Alashan wapiti are primarily forest dwellers and their smaller antler sizes is a likely adaptation to a forest environment.

Introductions

The Rocky Mountain elk subspecies has been reintroduced by hunter-conservation organizations in the Appalachian region of the eastern United States, where the now extinct Eastern elk once lived (Fitzgerald 2007). After elk were reintroduced in the states of Kentucky, North Carolina, and Tennessee, they migrated into the neighboring states of Virginia and West Virginia, and have established permanent populations there (Ledford 2005). Elk have also been reintroduced to a number of other states, including Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. As of 1989, population figures for the Rocky Mountain subspecies were 782,500, and estimated numbers for all North American subspecies exceeded 1 million (Peek 2007). Prior to the European colonization of North America, there were an estimated 10 million elk on the continent (RMEF 2007a).

Worldwide population of elk, counting those on farms and in the wild, is approximately 2 million.

Outside their native habitat, elk and other deer species were introduced in areas that previously had few if any large native ungulates. Brought to these countries for hunting and ranching for meat, hides, and antler velvet, they have proven highly adaptable and have often had an adverse impact on local ecosystems. Elk and red deer were introduced to Argentina and Chile in the early twentieth century. There they are now considered an invasive species, encroaching on Argentinian ecosystems where they compete for food with the indigenous Chilean Huemul and other herbivores (Galende et al. 2005). This negative impact on native animal species has led the IUCN to identify the elk as one of the world's 100 worst invaders (Flueck 2007). Both elk and red deer have also been introduced to Ireland and Australia (Corbet and Harris 1996).

The introduction of deer to New Zealand began in the middle of the nineteenth century, and current populations are primarily European red deer, with only 15 percent being elk (DF 2003). These deer have had an adverse impact on forest regeneration of some plant species, as they consume more palatable species, which are replaced with those that are less favored by the elk. The long term impact will be an alteration of the types of plants and trees found, and in other animal and plant species dependent upon them (Husheer 2007). As in Chile and Argentina, the IUCN has declared that red deer and elk populations in New Zealand are an invasive species (Flueck 2007).

Behavior

Adult elk usually stay in single-sex groups for most of the year. During the mating period known as the rut, mature bulls compete for the attentions of the cows and will try to defend females in their harem. Rival bulls challenge opponents by bellowing and by paralleling each other, walking back and forth. This allows potential combatants to assess the others' antlers, body size, and fighting prowess. If neither bull backs down, they engage in antler wrestling, and bulls sometimes sustain serious injuries. Bulls also dig holes in the ground, in which they urinate and roll their body. The urine soaks into their hair and gives them a distinct smell that attracts cows (Walker 2007).

Dominant bulls follow groups of cows during the rut, from August into early winter. A bull will defend his harem of 20 cows or more from competing bulls and predators (SDDGFP 2007). Only mature bulls have large harems and breeding success peaks at about eight years of age. Bulls between two to four years and over 11 years of age rarely have harems and spend most of the rut on the periphery of larger harems. Young and old bulls that do acquire a harem hold it later in the breeding season than do bulls in their prime. A bull with a harem rarely feeds and he may lose up to 20 percent of his body weight. Bulls that enter the rut in poor condition are less likely to make it through to the peak conception period or have the strength to survive the rigors of the oncoming winter (Walker 2007).

Bulls have a loud vocalization consisting of screams known as bugling, which can be heard for miles. Bugling is often associated with an adaptation to open environments such as parklands, meadows, and savannas, where sound can travel great distances. Females are attracted to the males that bugle more often and have the loudest call (Thomas and Toweill 2002). Bugling is most common early and late in the day and is one of the most distinctive sounds in nature, akin to the howl of the gray wolf.

Female elk have a short estrus cycle of only a day or two and matings usually involve a dozen or more attempts. By the fall of their second year, females can produce one and, very rarely, two offspring, though reproduction is most common when cows weigh at least 200 kilograms (450 pounds) (Sell 2007). The gestation period is 240 to 262 days and the offspring weigh between 15 and 16 kilograms (33 to 35 pounds). When the females are near to giving birth, they tend to isolate themselves from the main herd, and will remain isolated until the calf is large enough to escape predators (WDFW 2007).

Calves are born spotted, as is common with many deer species, and they lose their spots by the end of summer. Manchurian wapiti may retain a few orange spots on the back of their summer coats until they are older. After two weeks, calves are able to join the herd and are fully weaned at two months of age (MMMZ 2007). Elk calves weigh as much as an adult white-tailed deer by the time they are six months old (WERP 2007). The offspring will remain with their mothers for almost a year, leaving about the time that the next season's offspring are produced (Thomas and Toweill 2002). The gestation period is the same for all subspecies.

Elk live 20 years or more in captivity but average 10 to 13 years in the wild. In some subspecies that suffer less predation, they may live an average of 15 years in the wild (NPS 2007).

Protection from predators

Male elk retain their antlers for more than half the year and are less likely to group with other males when they have antlers. Antlers provide a means of defense, as does a strong front-leg kick, which is performed by either sex if provoked. Once the antlers have been shed, bulls tend to form bachelor groups which allow them to work cooperatively at fending off predators. Herds tend to employ one or more scouts while the remaining members eat and rest (Thomas and Toweill 2002).

After the rut, females form large herds of up to 50 individuals. Newborn calves are kept close by a series of vocalizations; larger nurseries have an ongoing and constant chatter during the daytime hours. When approached by predators, the largest and most robust females may make a stand, using their front legs to kick at their attackers. Guttural grunts and posturing are used with great effectiveness with all but the most determined of predators. Aside from man, wolf and coyote packs and the solitary cougar are the most likely predators, although brown, grizzly, and black bears also prey on elk (Thomas and Toweill 2002). In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which includes Yellowstone National Park, bears are the most significant predators of calves (Barber et al. 2005). Major predators in Asia include the wolf, dhole, brown bear, siberian tiger, Amur leopard, and snow leopard. Eurasian lynx and wild boar sometimes prey on the Asian wapiti (Geist 1998).

Migration

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem elk herd numbers over 200,000 individuals and, during the spring and fall, they take part in the longest elk migration in the continental U.S. Elk in the southern regions of Yellowstone National Park and in the surrounding National Forests migrate south towards the town of Jackson, Wyoming where they winter for up to six months on the National Elk Refuge. Conservationists there ensure the herd is well fed during the harsh winters (USFWS 2007). Many of the elk that reside in the northern sections of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem migrate to lower altitudes in Montana, mainly to the north and west.

As is true for many species of deer, especially those in mountainous regions, elk migrate into areas of higher altitude in the spring, following the retreating snows, and the opposite direction in the fall. Hunting pressure also impacts migration and movements (Jenkins 2001). During the winter, they favor wooded areas and sheltered valleys for protection from the wind and availability of tree bark to eat. Roosevelt elk are generally non-migratory due to less seasonal variability of food sources (Thomas and Toweill 2002).

Health issues

Brainworm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) is a parasitic nematode that has been known to affect the spinal cord and brain tissue of elk, leading to death. The nematode has a carrier in the white-tailed deer in which it normally has no ill effects. Nonetheless, it is carried by snails, which can be inadvertently consumed by elk during grazing (Fergus 2007).

Chronic Wasting Disease affects the brain tissue in elk and has been detected throughout their range in North America. First documented in the late 1960s in mule deer, the disease has affected elk on game farms and in the wild in a number of regions. Elk that have contracted the disease begin to show weight loss, increased watering needs, disorientation and listlessness, and at an advanced stage the disease leads to death. The disease is similar to but not the same as Mad Cow Disease, and no dangers to humans have been documented, nor has the disease been demonstrated to pose a threat to domesticated cattle (RMEF 2007d). In 2002, South Korea banned the importation of elk antler velvet due to concerns about chronic wasting disease (Hansen 2006).

Brucellosis occasionally affect elk in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, the only place in the U.S. where the disease is still known to exist. In domesticated cattle, brucellosis causes infertility, abortions, and reduced milk production. It is transmitted to humans as undulant fever, producing flu-like symptoms that may last for years. Though bison are more likely to transmit the disease to other animals, elk inadvertently transmitted brucellosis to horses in Wyoming and cattle in Idaho. Researchers are attempting to eradicate the disease through vaccinations and herd management measures, which are expected to be successful (USDA 2007).

Naming and etymology

While the term "elk" refers to Cervus canadensis in North America, the term elk refers to Alces alces in English-speaking Europe, a deer that is known as "moose" in North America. The American Indian "waapiti," meaning "white rump" and used by the Shawnees for this animal, has come to be a word, as "wapiti," that can more clearly distinguish Cervus canadensis.

Early European explorers to North America, who were familiar with the smaller red deer of Europe, believed that the much larger North American animal looked more like a moose, hence they used the common European name for the moose. The name elk is from the German word for moose, which is elch (PEH 2007).

The elk is also referred to as the maral in Asia, though this is due to confusion with the central Asian red deer, which is a very similar species.

Taxonomy

Subspecies

Elk ancestors of the Cervus genus first appear in the fossil record 12 million years ago, during the Pliocene in Eurasia, but they do not appear in the North American fossil record until the later Pleistocene ice ages, when they apparently crossed the Bering land bridge (USGS 2006). The extinct Irish Elk (Megaloceros) was not a member of the genus Cervus, but rather the largest member of the wider deer family (Cervidae) known from the fossil record (Gould 1977).

There are numerous subspecies of elk. Some recognize six subspecies from North America in recent historical times and five from Asia, although some taxonomists consider them different ecotypes or races of the same species (adapted to local environments through minor changes in appearance and behavior). Populations vary as to antler shape and size, body size, coloration and mating behavior. DNA investigations of the Eurasian subspecies revealed that phenotypic variation in antlers, mane and rump patch development are based on "climatic-related lifestyle factors" (Groves 2005).

Of the six subspecies of elk considered to have inhabited North America in recent times, four remain, including the Roosevelt (C. canadensis roosevelti), Tule (C. canadensis nannodes), Manitoban (C. canadensis manitobensis), and Rocky Mountain (C. canadensis nelsoni) (Keck 2007). The Eastern elk (C. canadensis canadensis) and Merriam's elk (C. canadensis merriami) subspecies have been extinct for at least a century (Gerhart 2007; Allen 2007). Classification of the four surviving North American groups as subspecies is maintained, at least partly, for political purposes to permit individualized conservation and protective measures for each of the surviving populations (Geist 1993).

Five subspecies found in Asia include the Altai (C. canadensis sibiricus), the Tianshan (C. canadensis songaricus), and the Asian wapitis (C. canadensis asiaticus), also known as the Siberian elk. Two distinctive subspecies found in China and Korea are the Manchurian (C. canadensis xanthopygus) and the Alashan wapitis (C. canadensis alashanicus). The Manchurian wapiti is darker and more reddish in coloration than the other populations. The Alashan wapiti of north central China is the smallest of all subspecies, has the lightest coloration and is the least studied (Geist 1998).

Valerius Geist, who has written on the world's various deer species, holds that there are only three subspecies of elk. Geist maintains the Manchurian and Alashan wapiti but places all other elk into C. canadensis canadensis (Geist 1993).

DNA research

Until 2004, red deer and elk were considered to be one species, Cervus elaphus, based on fertile hybrids that have been produced in captivity. Recent DNA studies, conducted on hundreds of samples from red deer and elk subspecies as well as other species of the Cervus deer family, showed that there are three distinct species, dividing them into the east Asian and North American elk (wapiti) (C. canadensis), the central Asian red deer (C. affinis), and the European red deer (C. elaphus) (Ludt et al. 2004).

The previous classification had over a dozen subspecies under the C. elaphus species designation; DNA evidence concludes that elk are more closely related to central Asian red deer and even sika deer than they are to the red deer (Ludt et al. 2004). Though elk and red deer can produce fertile offspring in captivity, geographic isolation between the species in the wild and differences in mating behaviors indicate that reproduction between them outside a controlled environment would be unlikely (Geist 1998).

Cultural references

Elk have played an important role in the cultural history of a number of peoples.

Pictograms and petroglyphs of elk were carved into cliffs thousands of years ago by the Anasazi of the southwestern United States. More recent Native American tribes, including the Kootenai, Cree, Ojibwa, and Pawnee, produced blankets and robes from elk hides.

The elk was of particular importance to the Lakota and played a spiritual role in their society (RMEF 2007e). At birth, Lakota males were given an elk's tooth to promote a long life since that was seen as the last part of dead elk to rot away. The elk was seen as having strong sexual potency and young Lakota males who had dreamed of elk would have an image of the mythical representation of the elk on their "courting coats" as a sign of sexual prowess. The Lakota believed that the mythical or spiritual elk, not the physical one, was the teacher of men and the embodiment of strength, sexual prowess, and courage (Halder 2002).

Neolithic petroglyphs from Asia depict antler-less female elk, which have been interpreted as symbolizing rebirth and sustenance. By the beginning of the Bronze Age, the elk is depicted less frequently in rock art, coinciding with a cultural transformation away from hunting (Jacobson 1993).

Commercial uses

Elks have traditionally been hunted for food, sport, and their hides. For thousands of years, elk hides have been used for tepee covering, blankets, clothing, and footwear. Modern uses are more decorative, but elk skin shoes, gloves, and belts are sometimes produced.

Elk are held in captivity for a variety of reasons. Hunting interests set aside game farms, where hunters can pay a fee and have a greatly increased chance to shoot an elk, as they are fenced in and have less opportunity to escape. They are not generally harvested for meat production on a large scale; however, some restaurants offer the meat as a specialty item and it is also available in some grocery stores.

Elk meat has a taste somewhere between beef and venison and is higher in protein and lower in fat than either beef or chicken (Wapiti.net 2007). Elk meat is also a good source of iron, phosphorus, and zinc, but is high in cholesterol (ND 2007).

A male elk can produce 10 to 11 kilograms (22 to 25 pounds) of antler velvet annually. On ranches in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand, this velvet is collected and sold to markets in east Asia, where it is used in medicine. Velvet is also considered by some cultures to be an aphrodisiac.

Antlers also are used in artwork, furniture, and other novelty items. All Asian subspecies, along with other deer, have been raised for their antlers in central and eastern Asia by Han Chinese, Turkic peoples, Tungusic peoples, Mongolians, and Koreans. Elk farms are relatively common in North America and New Zealand.

Since 1967, the Boy Scouts of America have assisted employees at the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming by collecting the antlers that are shed each winter. The antlers are then auctioned with most of the proceeds returned to the refuge. In 2006, 3,200 kilograms (7,060 pounds) of antlers were auctioned, bringing in almost USD$76,000. Another 980 kilograms (2,160 pounds) were sold directly for local use, restoring some decorative arches in the Jackson Town Square (USFWS 2006).

Notes

- ↑ Erxleben, J.C.P. (1777) Anfangsgründe der Naturlehre and Systema regni animalis.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, C. Elk reintroductions. U.S. Geological Survey(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Corbet, G. B., and S. Harris. The Handbook of British Mammals. Blackwell Science, 1996. ISBN 978-0865427112.

- Eide, S. Roosevelt elk. Alaska Department of Fish and Game(1994). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Fergus, C. Elk. Pennsylvania Game Commission (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Flannery, T. The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and Its Peoples. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001. ISBN 0871137895.

- Flueck, W. Cervus elaphus (mammal). Global Invasive Species Database, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Galende, G., E. Ramilo, and A. Beati. Diet of Huemul deer (Hippocamelus bisulcus) in Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 40(1): 1-5. 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Geist, V. Elk Country. Minneapolis: Northword Press, 1993. ISBN 978-1559712088.

- Geist, V. Deer of the World: Their Evolution, Behavior, and Ecology. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0811704960.

- Gould, S. J. The misnamed, mistreated, and misunderstood Irish elk. 79–90 in Ever Since Darwin. W.W. Norton, New York, 1977. ISBN 0393009173.

- Husheer, S. W. Introduced red deer reduce tree regeneration in Pureora Forest, central North Island, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 31(1). (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Jacobson, E. The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia: A Study in the Ecology of Belief. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Academic Publishers, 1993. ISBN 978-9004096288.

- Keck, S. [http://www.bowhunting.net/NAspecies/elk1.html#subspecies Elk (Cervus canadensis). Bowhunting.net (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- National Park Service (NPS). 2007. Elk. Great Smoky Mountains. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Peek, J. M. North American elk. U.S. Geological Survey(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Robb, B, and G. Bethge. The Ultimate Guide to Elk Hunting. The Lyons Press, 2001. ISBN 1585741809.

- Sell, R. Elk. North Dakota State University, Alternative Agriculture Series(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021

- Thomas, J. W., and D. Toweill. Elk of North America, Ecology and Management. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 158834018X.

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services. Brucellosis and Yellowstone Bison. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services, USDA (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). National Elk Refuge. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). Ecosystem and climate history of Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey (2006). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology (UMMZ). Cervus elaphus. Animal Diversity Web(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Walker, M. The red deer. World Deer Website (2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- Wapiti.net. Elk meat nutritional information. Wapiti.net(2007). Retrieved December 31, 2021.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.