Altai Mountains

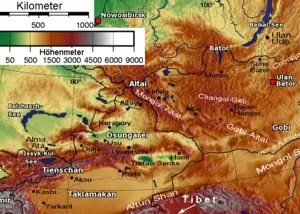

The Altay Mountains, Russian Altay, Mongolian Altayn Nuruu, Chinese (Wade-Giles romanization) A-erh-t'ai Shan; Russian Алтай; Алтай, Altai). Mountain system or mountain range of Central Asia that extends approximately 1,200 miles (2,000 km) in a southeast-northwest direction from the Gobi (desert) to the West Siberian Plain, through Chinese, Mongolian, Russian, and Kazak territory, where Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan come together, and where the great rivers Irtysh, Ob and Yenisei have their sources. The northwest end of the range is at 52° N and between 84° and 90° E (where it merges with the Sayan Mountains to the east), and extends southeast from there to about , where it gradually becomes lower and merges into the high plateau of the Gobi Desert. The mountains divide the waters of great rivers, such as the Ob, which flow northward to the Arctic, from those draining into the vast Central Asian interior basin. The name, in Turkic Alytau or Altay, means Al (gold), tau (mount); in Mongolian Altain nuruu (Алтайн нуруу), the "Mountains of Gold."

The Altay Mountains are known as the birthplace of the Turkic peoples, and the proposed Altaic language family takes its name from the mountain range. The indigenous Altai people represent an amalgamation of several Turkic tribes; today the area is inhabited by a mixture of Altai, who now number less than 20 percent of the population, and the descendants of Russian settlers. Modern industry includes agriculture, mining and the production of hydroelectric power. Tourists are increasingly attracted by the hot spring resorts and the picturesque mountain peaks and lakes.

Geography

In the north of the region is the Sailughem Mountains, also known as Kolyvan Altai, which stretch northeast from 49° N and 86° E towards the western extremity of the Sayan Mountains in 51° 60' N and 89° E. Their mean elevation is 1,500 to 1,750 m. The snow-line runs at 2,000 m on the northern side and at 2,400 m on the southern, and above it the rugged peaks tower up some 1,000 m more. Mountain passes across the range are few and difficult, the chief being the Ulan-daban at 2,827 m (2,879 m according to Kozlov), and the Chapchan-daban, at 3,217 m, in the south and north respectively. On the east and southeast this range is flanked by the great plateau of Mongolia, the transition being effected gradually by means of several minor plateaus, such as Ukok (2380 m with Pazyryk valley), Chuya (1,830 m), Kendykty (2,500 m), Kak (2,520 m), Suok (2,590 m), and Juvlu-kul (2,410 m).

This region is studded with large lakes, including Uvs Nuur ( 720 m above sea level), Kirghiz-nor, Durga-nor and Khovd Nuur 1,170 m, and traversed by various mountain ranges, of which the principal are the Tannu-Ola Mountains, running roughly parallel with the Sayan Mountains as far east as the Kosso-gol, and the Khan-khu Mountains, also stretching west and east.

The north-western and northern slopes of the Sailughem Mountains are extremely steep and difficult to access. On this side lies the highest summit of the range, the double-headed Belukha, whose summits reach 4,506 m (14,783 ft) and 4,440 m (14,563 ft) respectively, and give origin to several glaciers (30 square kilometeres in aggregate area, as of 1911). Here also are the Kuitun (3,660 m; 12,004 ft)) and several other lofty peaks. Numerous spurs, striking in all directions from the Sailughem mountains, fill up the space between that range and the lowlands of Tomsk. Such are the Chuya Alps, having an average altitude of 2,700 m, with summits from 3,500 to 3,700 m, and at least ten glaciers on their northern slope; the Katun Alps, which have a mean elevation of about 3,000 m and are mostly snow-clad; the Kholzun range; the Korgon 1,900 to 2,300 m, Talitskand Selitsk ranges; the Tigeretsk Alps.

Several secondary plateaus of lower altitude are also distinguished by geographers, The Katun valley begins as a wild gorge on the south-west slope of Belukha; then, after a big bend, the river (600 km long) pierces the Katun Alps, and enters a wider valley, lying at an altitude of from 600 to 1,100 m, which it follows until it emerges from the Altai highlands to join the Biya River in a most picturesque region. The Katun River and the Biya together form the Ob River.

The next valley is that of the Charysh, which has the Korgon and Tigeretsk Alps on one side and the Talitsk and Bashalatsk Alps on the other. This, too, is very fertile. The Altai, seen from this valley, presents romantic scenes, including the small but deep Kolyvan lake (altitude 360 m), which is surrounded by fantastic granite domes and towers.

Farther west the valleys of the Uba, the Ulba and the Bukhtarma open south-westwards towards the Irtysh. The lower part of the first, like the lower valley of the Charysh, is thickly populated; in the valley of the Ulba is the Riddersk mine, at the foot of the Ivanovsk Peak (2,060 m), clothed with alpine meadows. The valley of the Bukhtarma, which has a length of 320 km, also has its origin at the foot of the Belukha and the Kuitun peaks, and as it falls some 1,500 m in about 300 km, from an alpine plateau at an elevation of 1,900 m to the Bukhtarma fortress (345 m), it offers striking contrasts of landscape and vegetation. Its upper parts abound in glaciers, the best known of which is the Berel, which comes down from the Byelukha. On the northern side of the range which separates the upper Bukhtarma from the upper Katun is the Katun glacier, which after two ice-falls widens out to 700 to 900 meters. From a grotto in this glacier the Katun river bursts tumultuously.

The middle and lower parts of the Bukhtarma valley have been colonized since the eighteenth century by runaway Russian peasants, serfs and religious schismatics (Raskolniks), who created a free republic there on Chinese territory; and after this part of the valley was annexed to Russia in 1869, it was rapidly colonized. The high valleys farther north, on the same western face of the Sailughem range, are but little known, their only visitors being Kirghiz shepherds.

The region of the Bashkaus, Chulyshman, and Chulcha Rivers, all three leading to the alpine Lake Teletskoye (length, 80 km; maximum width, 5 km; altitude, 520 m; area, 230.8 square kilometeres; maximum depth, 310 m; mean depth, 200 m), are inhabited by Telengit people. The shores of the lake rise almost sheer to over 1,800 m. From this lake issues the Biya, which joins the Katun at Biysk, and then meanders through the prairies of the north-west of the Altai.

Farther north the Altai highlands are continued in the Kuznetsk district, which has a slightly different geological aspect, but still belongs to the Altai system. But the Abakan River, which rises on the western shoulder of the Sayan mountains, belongs to the system of the Yenisei. The Kuznetsk Ala-tau range, on the left bank of the Abakan, runs north-east into the government of Yeniseisk, while a complex of mountains (Chukchut, Salair, Abakan) fills up the country northwards towards the Trans-Siberian railway and westwards towards the Ob.

The Ek-tagh or Mongolian Altai, which separates the Khovd basin on the north from the Irtysh basin on the south, is a true border-range, in that it rises in a steep and lofty escarpment from the Dzungarian depression (470 to 900 m), but descends on the north by a relatively short slope to the plateau (1,150 to 1,680 m) of north-western Mongolia. East of 94° E the range is continued by a double series of mountain chains, all of which exhibit less sharply marked orographical features and are at considerably lower elevations. The slopes of the constituent chains of the system are inhabited principally by nomad Kirghiz.

History, Ethnography and Inhabitants

Archaeological finds at Paleolithic sites indicate that the Altai were inhabited by some of the earliest human beings. Artifacts found in caves and burial mounds date from the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages. The modern population of the Altai is a mixture of indigenous Altais and Russian settlers.

The Altai people represent an amalgamation of several Turkic tribes. The earliest tribes were the Uighurs, Kypchak-Kimaks, Yenisey Kyrgyz, Oguz, and others. Around 550 C.E., the Tugyu Turks settled in the Altai Mountains along the headwaters of the Ob River and in the foothills of the Kuznetsk Alatau. In the eighth century, the Telengit and the Telesy migrated from the Tunlo river in Mongolia to the Altai Mountains. Around 900 C.E. the Kimak Tribal Union was formed, giving rise to the tribal designations Kumanda, Teleut, and Telengit.

The Altai was under the control of the Dzungarian state (based in northwestern China) until the eighteenth century. In 1758, the Chinese incorporated Dzungaria into Sinkiang, and conducted a campaign of genocide against the Altai peoples. During the eighteenth century the nomadic Altai came into contact with the Russians, who began to sedentarize them. An Orthodox mission was established, and the majority of Altai were converted to Orthodox Christians. Russia annexed the region in 1866. At the end of the nineteenth century, an anti-Russian messianic faith, burkhanizm (Lamaist Buddhism with elements of Shamanism) spread among the Altay, creating a foundation for a new nationalist movement which was crushed in 1904. In 1917, after the Bolshevik Revolution, Altai leaders sided with the Mensheviks, demanding the creation of a separate Oyrot republic.

The Soviet government gave the Altai nominal recognition by establishing the Oyrot Autonomous Oblast in 1922. In 1948, the term “Oyrot” was declared counter-revolutionary, and the name was changed to Gorno-Altay Autonomous Oblast. In 1991, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it became the Altai Republic.[1] In the twentieth century, Russian industrialization brought large numbers of ethnic Russians to the area, and by 1950 the Altais made up only 20 percent of the population.

Nature and Ecology

The rivers crisscrossing the Altai and Mongolian Altai ranges are fed predominantly by melted snow and summer rains. In the Gobi Altai, rivers are shorter, shallower, and often frozen in the winter and dry in the summer. The Altai contains more than 3,500 lakes, most of structural or glacial origin. The mountains divide the waters of the great rivers, such as the Ob, which flow northward to the Arctic, from those draining into the vast Central Asian interior basin.

Weather

The climate is continental with long, bitterly cold winters and, on the lower slopes, hot summers. On the exposed western mountain ridges, precipitation is heavy year-round, but decreases substantially to the east. The summer generally begins in May or June and lasts until September. The driest months are August and September. During the summer, snow remains only in the areas above 2600 meters. Snow begins to cover the entire mountain range in October or November. In the coldest months, January and February, the temperatures average minus 15 - 20 degrees Celcius (5 to -4 degrees Fahrenheit). The coldest area is the Chuyskaya steppe.

Vegetation and Wildlife

Four distinct vegetation zones comprise the Altai system: mountain subdesert, mountain steppe, mountain forest, and the alpine regions. Forests of conifers, birches, larches and aspens cover about 70 percent of the Altai itself but forests are almost nonexistent in the Mongolian and Gobi Altai.

The large mammals found in the Altai include bear, lynx, glutton (similar to a wolverine or carcajou), Siberian stag, reindeer and snow leopard (above the tree line). There are 230 species of birds, and 20 species of fish, including umber, loach, whitefish. Many of the plant and animal species are unusual and unique.

Economy

The Altai Mountains are known for their ore deposits and their potential to produce hydroelectric power. Large mines and smelters for nonferrous metals such as copper, lead, and zinc operate in the main range. Other major economic activities in the region are agriculture and the production of livestock, especially among the nomadic herders in the dry southern Mongolian Altai.

Tourists are attracted to the health resorts which have been developed around the region's mineral springs, and to the picturesque mountain peaks and lakes. A number of outdoor activities and sports are available, such as caving, skiing, snowboarding, hiking, mountaineering, horseback riding, bird watching, scenic drives, and rafting. The Chuya Rafting Rally on the Katun River is an international event.

World Heritage Site

A vast area of 16,175 km² - Altai and Katun Natural Reserves, Lake Teletskoye, Mount Belukha and the Ukok Plateau - comprise a natural UNESCO World Heritage Site entitled Golden Mountains of Altai. As stated in the UNESCO description of the site, "the region represents the most complete sequence of altitudinal vegetation zones in central Siberia, from steppe, forest-steppe, mixed forest, subalpine vegetation to alpine vegetation." While making its decision, UNESCO also cited Russian Altai's importance for preservation of the globally endangered mammals, such as snow leopard and the Altai argali, the world's largest wild sheep.[2]

Geology

The Siberian Altai represents the northernmost region affected by the tectonic collision of India into Asia. Massive fault systems run through the area, including the Kurai fault zone and the recently identified Tashanta fault zone. These fault systems are typically thrusts or right lateral strike-slip faults, some of which are tectonically active. Rock types in the mountains are typically granites and metamorphic schists, and some are highly sheared near to fault zones.

Seismic activity

On September 27, 2003 a massive earthquake, measuring MW 7.3, occurred in the Chuya Basin area to the south of the Altai region. Seismic activity is however a rare occurrence. This earthquake and its aftershocks devastated much of the region, causing $10.6 million in damage (USGS) and wiping out the village of Beltir.

Notes

- ↑ "Altay", Centre for Russian Studies, NUPI Retrived 2007-07-20

- ↑ Greater Altai – Altai Krai, Republic of Altai, Tyva (Tuva), and Novosibirsk - Crossroads. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grousset, René. 1970. The empire of the steppes; a history of central Asia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813506271 ISBN 9780813506272

- Herget, Jürgen. 2005. Reconstruction of Pleistocene ice-dammed lake outburst floods in the Altai Mountains, Siberia. Boulder, Colo: Geological Society of America. ISBN 0813723868 ISBN 9780813723860

- Reader's Digest Association. 2002. Vanished civilizations. London: Reader's Digest. ISBN 0276426584 ISBN 9780276426582

- Rerikh, Nikolaĭ Konstantinovich. 1929. Altai—Himalaya; a travel diary. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.

- Halemba, Agnieszka. 2006. The Telengits of Southern Siberia: landscape, religion, and knowledge in motion. Routledge contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe series. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415360005 ISBN 9780415360005

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2023.

- Golden Mountains of Altai UNESCO

- UNESCO's evaluation of Altai (PDF file)

- Archaeology and Landscape in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.