Democracy

Democracy is the name given to a number of forms of government and procedures which have legitimacy because they have the consent of the people they govern. The two main criteria for a democracy are firstly that the officials exercising power have legitimate authority because they have been elected as opposed to inheriting that authority or holding it by force; and secondly the mechanism for changing a ruler is through peaceful and regular elections as opposed to revolts, coups or civil war. Democracy is not a theory about what the aims or content of government or law should be. Only that those aims should be guided by the opinion of the majority as opposed to a single ruler as with an absolute monarchy or dictatorship or a small group as with an oligarchy. Just because a government has been democratically elected does not mean it will be a good, just or competant government. Thus some polities have used the democratic process to secure liberty while others have used it to promote equality, nationalism or other values.

Most of the procedures used by modern democracies are very old. Almost all cultures have at some time had their new leaders approved, or at least accepted, by the people; and have changed the laws only after consultation with the assembly of the people or their leaders. Such institutions existed since before written records as well as being referred to in ancient texts, and modern democracies are often derived or inspired by them, or what remained of them.

Democracy in the modern world evolved in Britain and France and was then spread to other places. The main reason for the development of democracy was a dissatisfaction with the corruption, incompetance, abuse of power and lack of accountability of the existing polity which was often an absolute monarchy whose legitimacy was based on the doctrine of the divine right of kings. The source of the legitimacy of democratic government is the people. There are many different types of democracy from the minimilist direct democracy found in Switzerland to the totalitarian democracy of communist states such as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea as well as mixed systems such as the blending of monarchy, oligarchy and democracy of the United Kingdom. As democracy is now regarded by many as the highest, or even only, form of legitimate authority many states claim to be democratic. One of the most damaging accusations is that a group or process is undemocratic. In the Islamic world there are democracies such as Turkey, Egypt, Iran and Pakistan although there are also Muslims who believe democracy is un-Islamic. Though the term democracy is typically used in the context of a political state, the principles are also applicable to other groups and organizations.

In the past philosophers from Plato and Aristotle to St. Thomas Aquinas and Hobbes have considered democracy to be among the worst forms of government because they could easily be corrupted and result in injustice. The chief danger is that a majority can impose its will upon a minority in a way that violates their liberties. Thus during the twentieth centuries as well as liberal democracies there were demogogues such as Hitler who came to power through the democractic process and totalitarian democracies like the Soviet Union.

To function properly democracies require a high level of education and maturity among the people who vote. Otherwise the process can be captured by demagogues if too many vote in a self-centered way as happened in Weimer Germany. It can also be very claustrophobic or oppressive as majorities can use their position to intimidate minority opinions. Modern democracy has benefited from the mass education of citizens, the free press and most especially the Protestant Reformation which encouraged self-restraint and public mindedness and trained people in self-government.

History

Ancient origins

The word "democracy" derives from the ancient Greek demokratia (δημοκρατία). It combines the elements demos (which means "people") and kratos ("force, power"). Kratos is an unexpectedly brutish word. In the words "monarchy" and "oligarchy", the second element arche means rule, leading, or being first. The Athenian democracy developed in the Greek city-state of Athens (comprising the central city-state of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica). Athens was one of the very first known democracies and probably the most important in ancient times. Every adult male citizen was by right a member of the Assembly and had a duty to participate and vote on legislation and executive bills. The officials of the democracy were elected by lot except generals (strategoi) and financial officials who were elected by the Assembly. Election was seen as less democratic and open to corruption because it would favor the rich (who could buy votes) and the eloquent whereas a lottery gave everyone an equal chance to participate and experience in Aristotle's words, "ruling and being ruled in turn" (Politics 1317b28–30). Participation was not open to all the inhabitants of Attica, but the in-group of participants was constituted with no reference to economic class and they participated on a scale that was truly phenomenal. Never before had so many people spent so much of their time in governing themselves. However they only had the time to do this because of the huge number of slaves that underpined the Athenian economy. Political rights and citizenship, were not granted to women, slaves, or metics (aliens). Of the 250-300,000 inhabitants about one third were from citizen familes and about 30,000 were citizens. Of those 30,000 perhaps 5,000 might regularly attend one or more meetings of the popular Assembly.

Athenian polity was an expression of its philosophy. One of the distinguishing features of ancient Greece was its lack of a priestly class who would mediate between the people and the gods and also be channels of the divine laws and will. Instead the philosopher Aristotle summed the humanistic Greek view up in his definition of human beings as ‘political or social animals’ or as another philosopher put it, 'man is the measure of all things.' Men could only live perfect and self-sufficient lives if they became active citizens, knowing how to rule and be ruled by participating fully in the life of the state. Thus for Athenians making laws and arguing about policy was their duty and right. This contrasts with a religiously based culture where it is the gods who make or hand down the laws and human beings do not have the authority to make or change these laws. So individual citizens of Athens had the right to take the initiative: to stand to speak in the assembly, to initiate a public law suit (that is, one held to affect the political community as a whole), to propose a law before the lawmakers or to approach the council with suggestions.

There were many critics of Athenian democracy and twice it suffered coups. For example in 406 B.C.E. the Athenians won a naval victory over the Spartans. After the battle a storm arose and the eight generals in command failed to collect survivors: the Athenians sentenced all of them to death. Technically, it was illegal, as the generals were tried and sentenced together, rather than one by one as Athenian law required. Socrates happened to be the citizen presiding over the assembly that day. He refused to cooperate objecting to the idea that the people should be able to ignore the laws and do whatever they wanted just because they were in the majority. This tension in democracy between the rule of law and the rule of the people has constantly resurfaced throughout history. It was under a later democratic government that Socrates himself was executed which is partly why both Plato and Aristotle were so critical of democracy.

Middle Ages

Most parts of Europe were ruled by clergy or feudal lords during the Middle Ages. However, the growth of centers of commerce and city states led to great experimentation in non-feudal forms of government. Many cities elected mayors or burghers. There were various systems involving elections or assemblies, although often only involving a minority of the population. Such city states, particularly on the Italian peninsular, often allowed greater freedom for science and the arts, and the Renaissance blossomed in this environment, helping to create conditions for the re-emergence of democracy.

One of the most significant influences on the development of democracy was Protestantism. Non-conformists wanted to choose their own minister instead of having one appointed.

Instances of democracy that have been cited include Gopala in Bengal, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Althing in Iceland, certain medieval Italian city-states such as Venice, the tuatha system in early medieval Ireland, the Veche in Slavic countries, Scandinavian Things and the autonomous merchant city of Sakai in the 16th century in Japan. However, few of these have an unbroken history into the modern period an exception being the Althing which lays claim to being the oldest parliament in the world. Furthermore participation in many of these post-feudal governments was often restricted to the aristocracy.

The development of liberal democracy

The origin of the modern democracy that has expanded so rapidly in the past century lies in the evolution of English political institutions. The government of the English in the 10th century before the Norman conquest and the imposition of feudalism, was derived from the customs of the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled in England in the fifth century. The English were a nation of freeholders living in homesteads. A group of these homesteads formed a village which had an assembly, the village-moot presided over by the village-reeve. A 100 or so of such villages constituted a Hundred which, like the village, also had a meeting presided over by an elder where they managed their own affairs. A number of hundreds formed a shire presided over by an earldorman appointed by the King and Witan. The kingdom made up of these shires was ruled by the Witenagemot and the King. The Witenagemot was the "Meeting of the Wise Men" who could elect and depose the King, decide questions of war and peace, make and amend the laws, confirm the appointment of bishops and earldormen and settle disputes. The King was greatly respected but could not alter the law, levy a tax or make a grant of land without the consent of the Witenagemot.

The English system of government worked from below upwards, from the freeman to the King, every man holding his own land as his right, choosing his own earldorman who in turn helped to choose the King. The law was customary law which formed the basis of Common Law, a body of general rules prescribing social conduct. It was characterized by trial by jury and by the doctrine of the supremacy of law. The law was not made but discovered as revealed in the traditional life and practices of the community. It was thought of as God's law which had been handed down through custom from generation to generation. Thus no one had the authority to unilaterally go against the wisdom of the past generations and make new law.

In 1066 William the Conqueror invaded England and imposed the feudal system which worked from the top down. The King owned all the land and gave it to his knights, earls, and barons. In this way he gathered up, and concentrated in himself, the whole power of the state. Subsequent English history has been a long struggle to reassert the Anglo-saxon principles of government against this imposed feudalism.

Some landmarks in this not always progressive struggle were: the attempt to bring the Church under the law of the land so that priests who committed murder could be punished (1164); the confirmation of trial by jury (1166); Magna Carta, issued by King John under pressure from the barons lead by the Archbishop of Canterbury which in restated the ancient principle that no person should be imprisoned but by the judgement of his equals and by the law of the land (1215); the Provisions of Oxford which demanded that there should be three Parliaments a year and that the King could not act without the authority of his appointed advisors (1258); the first House of Commons summoned by Simon de Montefort with representatives from all classes of the kingdom (1265); the First Complete Parliament (1297) summoned by Edward I on the principle that, "it was right that what concerned all, should be approved by all," which passed the statute that there was to be no taxation without the consent of the realm; the right of the Commons to impeach any servant of the Crown who had done wrong (1376) and the necessity that the two Houses of Parliament should concur for the law to be changed; the abolition of the authority of the Pope in England (1534); the growth of non-conformity that accompanied the reformation popularised the idea that a congregation should be able to elect its own minister - this expansion of democracy in Christianity spread to the political realm; Parliament's assertion that its right to control its own elections and that its privileges are of right and not grace; the declaration by the Commons that their privileges were not the gift of the Crown, but the natural birthright of Englishmen, that they could discuss matters of public interest and that they had the right to liberty of speech (1621); the Petition of Right (1628) which demanded that no man could be taxed without consent of Parliament; the National Covenant (1637) signed in Scotland to resist the imposition of Popery and Episcopacy; the abolition of the Star Chamber (1640) which dispensed arbitrary justice and the English Civil War which arose because of the arbitrary government of Charles I who tried to rule without Parliament; the extraordinary amount of religious freedom and outpouring of spirituality at this time; the Habeas Corpus Act (1679) restated the ancient principle that indefinite and illegal imprisonment was unlawful; the Glorious Revolution in which William of Orange was invited to defend the rights and liberties of the people of England from James II who wanted to rule absolutely and impose Catholicism on the country; the Toleration Act (1689) allowing freedom of worship to all Protestants; the Declaration of Right (1689) that declared illegal the pretended power to suspend or dispense the law; the expansion of the franchise in England in the mid 19th Century through the Reform Acts (1832, 1867) which expanded the franchise and made representation more equitable; Ballot Act (1872) which introduced secret ballots; Corrupt and Illegal Practices Prevention Act (1883) which set limits on campaign spending; Representation of the People Act (1918) which gave the vote to all men and women over the age of 30. Universal suffrage and political equality of men and women wasn't acheived until 1928.

The main theme running through this political evolution is that the impetus for greater democracy was the desire preserve and expand freedom under the rule of law - the freedom of religion, association and ownership of property. To acheive this the importance of a separation of powers, or more importantly functions, came to recognized with an independent executive, legislature and judiciary. Hence the name liberal democracy. It was thought that a democratically accountable government was the best way to prevent the King from usurping his position and acting arbitrarily. Today the monarch still retains considerable latent power that he or she can and would be expected to use in certain circumstances. But basically the monarch now stands above party politics and is seen as a person, almost a parent figure, representing and unifying the nation and linking the past, present and future. Just as Athenian democracy was an expression of Greek philosophy, British democracy has been deeply influenced by the spirit of Christianity. Even the socialist party and trade unions have Christian origins.

However, with the expansion of the franchise came the expansion of government as politicians made promises to the electorate so as to win votes and be elected. These policies could only be delivered through greatly increased public expenditure financed through a huge increase in taxation. This has led to a gradual but significant loss of freedom as governments have used their democratic mandate to engage in social engineering, retrospective legislation and the confiscation of property in a manner reminiscent of the Greek abuses that Socrates railed against. It is now commonly thought that the will of a democratically elected government should not be constrained because this would be undemocratic whereas the whole raison d'etre of democracy was to preserve and not to justify the destruction of liberty.

A significant further development of democracy occurred with the establishment of the United States. The political principles of liberal democracy that were worked out over the centuries in England and articulated by the philosophers Locke and Hume were inherited by the United States and embodied in its constitution. Although not described as a democracy by its founding fathers, today it is regarded by many as the model for other countries to aspire too. The people who framed the constitution wanted to establish institutions that could preserve liberty and prevent the excessive growth of government which was seen as the chief threat to liberty. The United States Constitution set down the framework for government with checks and balances based on the separation of power so that no institution or person would have absolute power. It was adopted in 1788 and provided for an elected government through representatives, and it protected the civil rights and liberties of all except slaves. This exception came to haunt the new republic.

The system gradually evolved, from Jeffersonian Democracy to Jacksonian Democracy and beyond. Following the American Civil War, in 1868, newly freed slaves, in the case of men, were granted the right to vote under the passage of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. Women's suffrage was finally acheived in the 1920s with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

The development of totalitarian democracy

Democracy when it developed on the continent of Europe took a very different turn. Throughout the Middle Ages continental monarchies had been very powerful, with the unchecked authority to lead their countries into ruinous and destructive wars. In the modern era the most progressive monarchs were enlightened despots. In theory France too was an absolute monarchy in which the king was the source of all laws and administrative authority. In practice the monarch was hedged in by a medieval constitution which he could not change without risking undermining the whole structure. The French state in the 1780s was on the brink of bankruptcy due to an ancient, inequitable and inadequate tax base as well as over spending on wars with Britain. There were many other economic and social problems the monarchy was unable to solve. This led to a widespread disatisfaction with the status quo and a desire for change. To break the deadlock the King called the Estates General, whose status and authority was very unclear, to meet for the first time since 1614. The forces that were unleashed soon resulted in the collapse of royal authority and social order. The Estates General turned itself into a National Assembly in 1789 and abrogated to itself the national sovereignty and right to create a new constitution. The Assembly swept aside the past creating a constitution which revolutionised the whole social and political structure of France. Feudalism, legal privilege and theocratic absolutism were abolished and society was rationally reorganised on an individualist and secular basis. Many of these changes such as legal equality and the abolition of feudal dues were welcomed by the general population.

The Declaration on the Rights of Man and Citizen was published guaranteeing legal equality; the separation of Church and State and religious toleration in 1791. Many of these changes were welcomed with few regreting the end of theocratic monarchy. In 1792 another assembly called the Convention drew up a republican constitution and voted to execute the king. People opposed to the revolution were arrested and executed in the Terror that followed. The revolution became increasingly radical and atheistic and there was a campaign of dechristianisation in 1794. An altar to the Cult of Reason replaced the Christian one in Notre Dame and many priests were martyred; 1789 was declared to be year zero and a new calendar without Sunday was proclaimed. The old currency was replaced with a decimal one and a new metric system of measurements proclaimed. There followed a series of wars with other neighbouring countries to defend and promote the revolution. In 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in a coup d'etat. Ironically in a country that had supposedly rejected absolute monarch, he was made Emperor of France and with more real power than any French king exported and imposed the principles of the revolution and French law and adminstrative practices on most of Europe.

The French Enlightenment provided the background to the French Revolution and the type of democracy that developed. It was rationalist assuming that a model society could be designed on rational principles and then implemented. It was also deeply anti-clerical and eventually turned atheistic as the French religious establishment was unable to intellectually refute the more extreme deist ideas that had been imported from England. The leading French philosopher Rousseau's conception of democracy was very illiberal. He thought that in order to be free every individual had to surrender his rights to a collective body and obey the general will. The general will is not necessarily what the majority want. It is what they ought to want even if they don't realise it. It is by being forced if necessary to obey this general will unconditionally that a person finds their true and free self. The state has total power which is legitimate because it has the consent of the majority. The general will by definition is always right and reflects the real interests of every member of society. So anyone who disagrees with the general will is mistaken and acting contrary to his own best interests. It is the ruler's responsibility to correct him and force him to be good for his own benefit. All that matters is the whole of which an individual is a part. [1]

So the chief impetus behind French democracy was the desire to seize the power of the state and use it to remodel society on a rationalistic basis. The vision was of a country organised and united to acheive a common purpose. As long as the government was based on popular sovereignty it had the power and authority to make any laws. This innovation was very attractive to others who wished to change and modernize society and became the basis of European democracy. Being rationalistic the supporters of the French Revolution thought its principles were universal and could or indeed should be adopted by others.

The principles of French democracy were eagerly embraced by other idealistic revolutionaries throughout Europe. It justified a small group, who thought they knew what was best for the people, seizing power in the name of the people, and using that power to compel the people to fit into the new ideal economic and social order. People who resisted or disagreed were at best sent to re-education camps or at worst eliminated. This is basically what happened in the communist democracies set up in the Soviet Union, The People's Republic of China and elsewhere. These countries are one party states based on the principles of democratic centralism; have a centrally planned command economy and a powerful secret police to seek out and punish dissenters.

This vision of democracy underpins the culture and institutions of the European Union.

20th Century

The transitions of the 20th century to democracy have come in successive "waves of democracy," variously resulting from wars, revolutions, decolonization, and economic circumstances. World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires resulted in the creation of new nation-states in Europe, most of them partly democratic. Several were rather unstable and strong men came power either to establish national unity or to defend the country from predatory larger neighbours. The Great Depression also brought disenchantment and instability and in several European countries dictators and fascist parties came to power either by coups or by manipulating the democratic system claiming to be able to solve problems which liberalism and democracy could not. Fascism and dictatorships flourished in Nazi Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Poland, the Baltics, the Balkans, Brazil, Cuba, China, and Japan, among others. Together with Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union, these made the 1930s the "Age of Dictators."[2] Even the United States allowed Franklin D. Roosevelt much more power than previous presidents which led to a huge expansion of government .

The aftermath of World War II brought a definite reversal of this trend in Western Europe and Japan. With the support of the USA and UK, liberal democracies were established in all the liberated countries of western Europe and the American, British, and French sectors of occupied Germany were democratised too. However in most of Eastern Europe, socialist democracies were imposed by the Soviet Union where only communist and communist supporting parties were allowed to participate in elections. Membership of these parties was restricted which disenfranchised most of the population. The communist party maintained itself in power through the use of intimidation and force imprisoning and killing any opponents. The Soviet sector of Germany became the German Democratic Republic and was forced into the Soviet bloc.

The war was followed by decolonization, and again most of the new independent states had democratic constitutions often based on the British parlimentary model. However, once elected many rulers held their power for decades by intimidating and imprisoning opponents. Elections when they were held were often rigged so that the ruling party and president was re-elected. Following World War II, most western democratic nations had mixed economies and developed a welfare state, reflecting a general consensus among their electorates and political parties that the wealthy could be taxed to help support the poor.

In the 1950s and 1960s, economic growth was high in both the western and Communist countries as industries were developed to provide goods for citizens. However, it later declined in the state-controlled, command economies, where incentives for hard work and the freedom to innovate were lost. By 1960, the vast majority of nation-states called themselves democracies, although the majority of the world's population lived in nations that experienced sham elections, and other forms of subterfuge.

A subsequent wave of democratization brought new liberal democracies in several nations such as Spain and Portugal. Some of the military dictatorships in South America became democratic in the late 1970s and early 1980s as dictators were unable to pay the national debts accumulated during their rule due to theft and the misuse of loans. This was followed by nations in East and South Asia by the mid- to late 1980s, that were becoming industrial producers.

In 1989 the Soviet Union collapsed economically, ending the Cold War and discrediting government-run economies. The former Eastern bloc countries had some memory of liberal democracy and could reorganize more easily than Russia, which had been communist since 1917. The most successful of the new democracies were those geographically and culturally closest to western Europe, and they quickly became members or candidate members of the European Union. Russia, however, had its reforms impeded by a mafia that crippled new businesses and the old party leaders who took personal ownership of Russia's outdated industries.

The liberal trend spread to some nations in Africa in the 1990s, most prominently in South Africa, where apartheid was dismantled by the efforts of Nelson Mandela and F.W. deKlerk. More recent examples include the Indonesian Revolution of 1998, the Bulldozer Revolution in Yugoslavia, the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan.

The Republic of India is currently the largest liberal democracy in the world.[3]

Forms of democracy

|

List of forms of government

|

There are many variations on the forms of government that put ultimate rule in the citizens of a state:

Representative Democracy

Representative democracy involves the selection of the legislature and executive by a popular election. Representatives are to make make decisions on behalf of those they represent. They retain the freedom to exercise their own judgment. Their constituents can communicate with them on important issues and choose a new representative in the next election if they are dissatisfied.

There are a number of systems of varying degrees of complexity for choosing representatives. They may be elected by a particular district (or constituency), or represent the electorate as a whole as in many proportional systems.

Liberal Democracy

Classical liberal democracy is normally a representative democracy along with the protection of minorities, the rule of law, a separation of powers, and protection of liberties (thus the name liberal) of speech, assembly, religion, and property.

Since the 1960s the term "liberal" has been used, often perjoratively, towards those legislatures that are liberal with state money and redistribute it to create a welfare state. However, this would be an illiberal democracy is classical terms, because it does not protect the property its citizens acquire.

Direct Democracy

Direct democracy is a political system in which the citizens vote on major policy decisions and laws. Issues are resolved by popular vote or referenda. Many people think direct democracy is the purest form of democracy. Direct democracies function better in small communities or in areas where everyone is self-sufficient and has little need of government, except for military defense. Switzerland is a direct democracy where new laws often need a referendum in order to be passed. It is also very decentralised with few policies being decided on a national level.

Socialist Democracy

Socialism, where the state economy is shaped by the government, has some forms that are based on democracy. Social democracy, democratic socialism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat are some examples of names applied to the ideal of a socialist democracy. Many democratic socialists and social democrats believe in a form of welfare state and workplace democracy produced by legislation by a representative democracy.

Marxist-Leninists, Stalinists, Maoists and other "orthodox Marxists" generally promote democratic centralism, but they have never formed actual societies which were not ruled by elites that had acquired government power. Libertarian socialists generally believe in direct democracy and Libertarian Marxists often believe in a consociational state that combines consensus democracy with representative democracy. Such consensus democracy has existed in local-level cell community groups in rural communist China.

Anarchist Democracy

The only form of democracy considered acceptable to many anarchists is direct democracy, which historically discriminates against minorities. Some anarchists oppose direct democracy. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognized that majority decisions are not binding on the minority, even when unanimous.[4] However, anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin criticized individualist anarchists for opposing democracy,[5] and says "majority rule" is consistent with anarchism.[6]

Sortition

Sortition (or Allotment) has formed the basis of systems randomly selecting officers from the population. A much noted classical example would be the ancient Athenian democracy. Drawing by lot from a pool of qualified people elected by the citizens, would be a democratic variation on sortition. Such a process would reduce the ability of wealthy contributors or election rigging to guarantee an outcome, and the problems associated with incumbent advantages would be eliminated.

Tribal and consensus democracy

Certain tribes such as the bushmen organized themselves using different forms of participatory democracy or consensus democracy.[7] However, these are generally face-to-face communities and it is difficult to develop consensus in a large impersonal modern bureaucratic state. Consensus democracy and deliberative democracy seek consensus among the people.[8]

Theory

Plato and Aristotle

Plato criticized democracy for a number of reasons. He thought the people were often muddle-headed and were not suited to choose the best leaders. Worse democracy tends to favour bad leaders who gain and maintain power by pandering to the people instead of telling them unpleasant truths or advocating necessary but uncomfortable policies. Furthermore in a democracy people are allowed to do what they like which leads to diversity and later social disintegration. It leads to class conflict between the rich and poor as the latter try to tax the former and redistribute their wealth. Morally, Plato said, democracy leads to permissiveness. The outcome he said the rise of a tyrrant to reimpose order.[11]

Aristotle contrasted rule by the many (democracy/polity), with rule by the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), and with rule by a single person (tyranny/monarchy or today autocracy). He thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system (he considered democracy to be the degenerate counterpart to polity).[12][13] He considered that democracy would be best suited to farmers that are self-sufficient and have no interest government, but when competing claims are made on a government good decisions are best made by knowledgeable leaders.

Montesquieu and the Separation of Powers

Separation of powers is a term coined by French political Enlightenment thinker Baron de Montesquieu (1685-1755) is a model for the governance of democratic states which he expounded in De l'Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws) which was published anonymously in 1748. Under this model, the state is divided into branches, and each branch of the state has separate and independent powers and areas of responsibility. The normal division of branches is into the Executive, the Legislative, and the Judicial. He based this model on the British constitutional system, in which he perceived a separation of powers among the monarch, Parliament, and the courts of law. Subsequent writers have noted that this was misleading, since Great Britain had a very closely connected legislature and executive, with further links to the judiciary (though combined with judicial independence). No democratic system exists with an absolute separation of powers or an absolute lack of separation of powers. Nonetheless, some systems are clearly founded on the principle of separation of powers, while others are clearly based on a mingling of powers.

Montesquieu was highly regarded in the British colonies in America as a champion of British liberty (though not of American independence). Political scientist Donald Lutz found that Montesquieu was the most frequently quoted authority on government and politics in colonial pre-revolutionary British America.[14] Following the American secession, Montesquieu's work remained a powerful influence on many of the American Founders, most notably James Madison of Virginia, the "Father of the Constitution." Montesquieu's philosophy that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another" reminded Madison and others that a free and stable foundation for their new national government required a clearly defined and balanced separation of powers.

Proponents of separation of powers believe that it protects democracy and forestalls tyranny; opponents of separation of powers, such as Professor Charles M. Hardin,[15] have pointed out that, regardless of whether it accomplishes this end, it also slows down the process of governing, promotes executive dictatorship and unaccountability, and tends to marginalize the legislature.

The U.S. Constitution states that the power comes from the people "We the people..." However, unlike a pure democracy, in a constitutional republic, citizens in the US are only governed by the majority of the people within the limits prescribed by the rule of law.[16] Constitutional Republics are a deliberate attempt to diminish the threat of mobocracy thereby protecting minority groups from the tyranny of the majority by placing checks on the power of the majority of the population. Thomas Jefferson stated that majority rights cannot exist if individual rights do not.[17] The power of the majority of the people is checked by limiting that power to electing representatives who govern within limits of overarching constitutional law rather than the popular vote or government having power to deny any inalienable right.[18] Moreover, the power of elected representatives is also checked by prohibitions against any single individual having legislative, judicial, and executive powers so that basic constitutional law is extremely difficult to change. John Adams defined a constitutional republic as "a government of laws, and not of men."[19]

The framers carefully created the institutions within the Constitution and the United States Bill of Rights. They kept what they believed were the best elements of previous forms of government. But they were mitigated by a constitution with protections for individual liberty, a separation of powers, and a layered federal structure. Inalienable rights refers to a set of human rights that are not awarded by human power, and cannot be surrendered.[20]

Beyond the public level

This article has discussed democracy as it relates to systems of public government. This generally involves nations and subnational levels of government, although the European Parliament, whose members are democratically directly elected on the basis of universal suffrage, may be seen as an example of a supranational democratic institution.

Aside from the public sphere, similar democratic principles and mechanisms of voting and representation have been used to govern other kinds of communities and organizations.

- Many non-governmental organizations decide policy and leadership by voting.

- In business, corporations elect their boards by votes weighed by the number of shares held by each owner.

- Trade unions sometimes choose their leadership through democratic elections. In the U.S. democratic elections were rare before Congress required them in the 1950s. [21]

- Cooperatives are enterprises owned and democratically controlled by their customers or workers.

The future of democracy

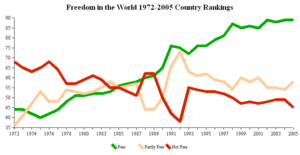

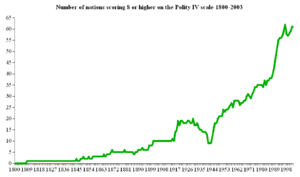

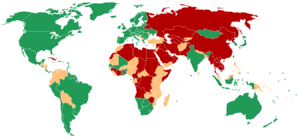

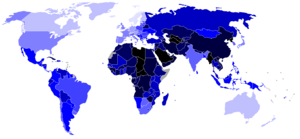

The number of liberal democracies currently stands at an all-time high and has been growing without interruption for several decades. As such, it has been speculated that this trend may continue in the future to the point where liberal democratic nation-states become the universal standard form of human society. This prediction formed the core of Francis Fukuyama's "End of History" theory. However the resurgence of Islam with a vision of a restored caliphate, the rise of China as an economic superpower while remaining a one party state and contraction of democracy in Russia has dented that prediction. Not everyone regards democracy as the only form of legitimate government. In some societies monarchy, aristocracy, one party rule or theocracy are still regarded as more legitimate. And that depends on the country's political culture and traditions which themselves are a product of its religion, geography, demography and historical experience. As these change and evolve so too will the country's polity.

See also

- Representative democracy

- Direct democracy

- Participatory democracy

- Deliberative democracy

- Democratic Peace Theory

- List of types of democracy

- Poll

- Media democracy

- Islamic democracy

- Sociocracy

- Democratization

Notes

- ↑ Younkins, Edward W. "Rousseau's General Will and Well Ordered Society." http://www.quebecoislibre.org/05/050715-16.htm Retrieved October 18, 2007

- ↑ Charles DiCola, Age of Dictators:Totalitarianism in the Interwar Period, http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:jCe2MTKLhzAJ:www.snl.depaul.edu/contents/current/syllabi/HC_314.doc+Stalin+1930%27s+%22Age+of+Dictators%22&hl=en&gl=us&ct=clnk&cd=1&lr=lang_en. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Michael Elliott, "India Awakens," Time, June 18, 2006, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1205374,00.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, General Idea of the Revolution, http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/ANARCHIST_ARCHIVES/proudhon/grahamproudhon.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Murray Bookchin, Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993-1998 (San Francisco: AK Press, 1999), 155.

- ↑ Murray Bookchin, Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm (San Francisco: AK Press, 1995), http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bookchin/soclife.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ John Kahionhes Fadden, The Six Nations Confederacy was and is likened to a longhouse, http://law.cua.edu/ComparativeLaw/Iroquois/. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson, Why Deliberative Democracy? (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), http://www.pupress.princeton.edu/titles/7869.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Gretchen Casper and Claudiu Tufis, "Correlation Versus Interchangeability: the Limited Robustness of Empirical Finding on Democracy Using Highly Correlated Data Sets," Political Analysis 11 (2003): 196-203.

- ↑ Freedom House, Methodology, http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=35&year=2005. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Plato, "The Republic", Translated with an Introduction by Desmond Lee, London: Penguin, 1974, ISBN 014044914 p.27-29.

- ↑ Aristotle, The Politics, Translated with an Introduction by Carnes Lord, Chicago:, University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 0226026698

- ↑ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.): General Introduction, http://www.iep.utm.edu/a/aristotl.htm. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ "The Relative Influence of European Writers on Late Eighteenth-Century American Political Thought," American Political Science Review 78,1(March, 1984), 189-197.

- ↑ "How the executive branch was formed, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Spring, 1991), pp. 391-396

- ↑ Sanford Levinson, Constitutional Faith (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 60.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, 1789, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, eds. Lipscomb and Bergh (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903-04), 7:455.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to James Monroe, 1797, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, eds. Lipscomb and Bergh (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903-04), 9:422.

- ↑ Sanford Levinson, Constitutional Faith (Princeton University Press, 1989), 60.

- ↑ U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Declaration of US Independence, 1776, http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/declaration_transcript.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ↑ Seymour Martin Lipset, Union Democracy (New York: Free Press, 1977).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allswang, John M. The Initiative and Referendum in California, 1898-1998. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780804738118

- Anderson, Gordon L. Philosophy of the United States: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2004. ISBN 1557788448

- Appleby, Joyce. Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780674530126

- Benhabib, Seyla, ed. Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780691044798

- Billington, Ray Allen. America's Frontier Heritage. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993. ISBN 9780826314635

- Blattberg, Charles. From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-829688-6

- Bookchin, Murray. Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993-1998. San Francisco: AK Press, 1999. ISBN 9781873176351

- Bookchin, Murray. Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm San Francisco: AK Press, 1995. http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/anarchist_archives/bookchin/soclife.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Cartledge, Paul. BBC - History - The Democratic Experiment. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/greeks/greekdemocracy_01.shtml. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Casper, Gretchen, and Claudiu Tufis. "Correlation Versus Interchangeability: the Limited Robustness of Empirical Finding on Democracy Using Highly Correlated Data Sets." Political Analysis 11 (2003): 196-203.

- Castiglione, Dario. "Republicanism and its Legacy." European Journal of Political Theory 4, no. 4 (2005): 453-65. http://www.huss.ex.ac.uk/politics/research/readingroom/CastiglioneRepublicanism.pdf#search=%22republicanism%20historiography%22. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Copp, David, Jean Hampton, and John E. Roemer, eds. The Idea of Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Dahl, Robert A. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. ISBN 0300049382

- Dahl, Robert A. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. ISBN 0300084552

- Dahl, Robert A., Ian Shapiro, and Jose Antonio Cheibub, eds. The Democracy Sourcebook. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003. ISBN 0262541475

- Dahl, Robert A. A Preface to Democratic Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1956. ISBN 0226134345

- Davenport, Christian. State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521864909

- Diamond, Larry, and Marc Plattner, eds. The Global Resurgence of Democracy. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780801853043

- Diamond, Larry, and Richard Gunther, eds. Political Parties and Democracy. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801868637

- Diamond, Larry, and Leonardo Morlino, eds. Assessing the Quality of Democracy. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 0801882877

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Philip J. Costopoulos, eds. World Religions and Democracy. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 0801880807

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Daniel Brumberg, eds. Islam and Democracy in the Middle East. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2003. ISBN 0801878470

- DiCola, Charles. Age of Dictators:Totalitarianism in the Interwar Period. http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:jCe2MTKLhzAJ:www.snl.depaul.edu/contents/current/syllabi/HC_314.doc+Stalin+1930%27s+%22Age+of+Dictators%22&hl=en&gl=us&ct=clnk&cd=1&lr=lang_en. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Downs, Anthony. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper Collins, 1957. ISBN 9780060417505

- Edmund, Morgan S. Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1989. ISBN 0393306232

- Elliott, Michael. "India Awakens." Time, June 18, 2006. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1205374,00.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Elster, Jon, ed. Deliberative Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521596963

- Fadden, John Kahionhes. The Six Nations Confederacy was and is likened to a longhouse. http://law.cua.edu/ComparativeLaw/Iroquois/. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Freedom House. Methodology. http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=35&year=2005. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The French Revolution. http://mars.wnec.edu/~grempel/courses/wc2/lectures/rev892.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Gabardi, Wayne. "Contemporary Models of Democracy." Polity 33, no. 4 (2001): 547+.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Dennis Thompson. Why Deliberative Democracy?. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. http://www.pupress.princeton.edu/titles/7869.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Heideking, Juergen, and James A. Henretta, eds. Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750-1850. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521800668

- Held, David. Models of Democracy. Polity Press, 2006. ISBN 9780745631479

- Inglehart, Ronald. Modernization and Post-modernization. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1997. ISBN 9780691011806

- Inoguchi, Takashi, Edward Newman, and John Keane. The Changing Nature of Democracy. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 1998. ISBN 9789280810059

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.): General Introduction. http://www.iep.utm.edu/a/aristotl.htm. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Letter to James Madison, 1789. In The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Lipscomb and Bergh, 7:455. Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903-04.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Letter to James Monroe, 1797. In The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, edited by Lipscomb and Bergh, 9:422. Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1903-04.

- Khan, L. Ali. A Theory of Universal Democracy: Beyond the End of History. Frederick: Kluwer Law International, 2001. ISBN 9041120033

- Kilcullen, R.J. Aristotle, The Politics. http://www.humanities.mq.edu.au/Ockham/y6704.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Levinson, Sanford. Constitutional Faith. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0300078935

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy." American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959): 69-105. http://www.jstor.org. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. Union Democracy. New York: Free Press, 1977. ISBN 9780029192108

- Macpherson, C. B. The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978. ISBN 9780192891068

- Madison, James. "The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection." Daily Advertiser, November 22, 1787. http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Federalist_Papers/No._10. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Merriam-Webster. Definition of democracy. http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/democracy. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Muhlberger, Steve. Democracy in Ancient India. http://www.nipissingu.ca/department/history/MUHLBERGER/HISTDEM/INDIADEM.HTM. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The National Archives. Citizenship - The Struggle for Democracy. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/struggle_democracy/getting_vote.htm. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The National Archives. Citizenship - Rise of Parliament. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/rise_parliament/making_history_rise.htm. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Newmyer, Jacqueline. "Present from the start: John Adams and America." Oxonian Review of Books 4, no. 2 (2005). http://www.oxonianreview.org/issues/2-2/2-2-6.htm. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Plattner, Marc F., and Aleksander Smolar, eds. Globalization, Power, and Democracy. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 0801865689

- Plattner, Marc F., and João Carlos Espada, eds. The Democratic Invention. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780801864193

- Putnam, Robert. Making Democracy Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 0691037388

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. General Idea of the Revolution. http://dwardmac.pitzer.edu/ANARCHIST_ARCHIVES/proudhon/grahamproudhon.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Raaflaub, Kurt A., Josiah Ober, and Robert W. Wallace. Origins of democracy in ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 0520245628

- Riker, William H. The Theory of Political Coalitions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962. ISBN 9780300008586

- Schumpeter, Joseph. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Routledge. 2006. ISBN 9780415107624

- Sen, Amartya K. "Democracy as a Universal Value." Journal of Democracy 10, no. 3 (1999): 3-17.

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Declaration of US Independence, 1776. http://www.archives.gov/national-archives-experience/charters/declaration_transcript.html. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Verba, Sidney. "Would the Dream of Political Equality Turn out to Be a Nightmare?." Perspectives on Politics 1, no. 4 (2003): 663-679. http://www.apsanet.org/imgtest/verba.pdf. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Weingast, Barry. "The Political Foundations of the Rule of Law and Democracy." American Political Science Review 91, no. 2 (1997): 245-263. http://www.jsstor.org. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Whitehead, Laurence, ed. Emerging Market Democracies: East Asia and Latin America. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2002. ISBN 080187217

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1993. ISBN 0679736883

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

- Journal of Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Open Directory at Open Directory Project Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democracy at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democracy Watch (International)—Worldwide democracy monitoring organization. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- IFES—supporting the building of democratic societies around the world Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democracy at large magazine—a quarterly magazine designed for professionals interested in democracy development worldwide Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- dgGovernance—Collection of resources on key issues of democracy and nation-building Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- the site of the Association for the School of Democracy a university-level research and training pluri- and transdisciplinary school of democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- "Islam and the Challenge of Democracy" by UCLA law professor Khaled Abou El Fadl in the April/May 2003 issue of Boston Review Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- New York Times argument against the "Development first, democracy later" idea Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The Rise of Illiberal Democracy by Fareed Zakaria Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- openDemocracy—Global democracy network using information, participation and debate to empower citizens. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Cosmopolitan democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Technologies of Measuring Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The Danger of Democratic Self-Destruction, Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- A New Nation Votes: American Elections Returns 1787-1825 Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Locate textbooks for children of age group 14 to 16 on DemocracyYou can download the soft versions of these books from this site by Selecting Class CLASS IX Selecting Subject Political Science Selecting Book title Political Science Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Global Social Change reports includes reports about global political change, in democracy and related political trends. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Critique

- The Democratic State - A Critique of Bourgeois Sovereignty Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Riff-Raff—Democracy as the Community of Capital - A Provisional Critique of Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The Crisis of Representative Democracy. Frankfurt a. M./Bern/New York: Peter Lang, 1987. Ed. by Hans Köchler. ISBN 3-8204-8843-X Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democracy, Liberty, Equality What is the relation between democracy and liberalism? (A Dialogue) Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Why democracy is wrong Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democracy, The God That Failed by Hans-Hermann Hoppe Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Liberty or Equality by Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Churchill on Democracy Revisited by J.K. Baltzersen Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- The INTERNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR DEMOCRACY, progressive scholarship, critiques of democracy. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Alternatives and improvements

- Republic Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democratic Manifesto Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Conducting new experiments with democracy, Ethics & Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Democratic Deficit Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- simpol.org—Plan to limit global competition and facilitate the emergence of a sustainable, sane global civilization. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Students for Global Democracy Retrieved August 17, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.