Difference between revisions of "Criminal law" - New World Encyclopedia

Cheryl Lau (talk | contribs) |

Cheryl Lau (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| − | + | The term '''criminal law''', sometimes called '''penal law''', refers to any of various bodies of rules in different [[jurisdiction]]s whose common characteristic is the potential for unique and often severe impositions as punishment for failure to comply. [[Criminal punishment]], depending on the [[offense]] and [[jurisdiction]], may include [[execution]], loss of [[liberty]], government supervision ([[parole]] or [[probation]]), or [[fine]]s. There are some archetypal crimes, like [[murder]], but the acts that are forbidden are not wholly consistent between different criminal codes, and even within a particular code lines may be blurred as civil infractions may give rise also to criminal consequences. Criminal law typically is enforced by the [[government]], unlike the [[Civil law (common law)|civil law]], which may be enforced by private parties. | |

| − | ''' | ||

| − | == | + | ==Criminal law history== |

| + | The first civilizations generally did not distinguish between civil and criminal law. The first known written codes of law were produced by the [[Sumerians]]. In the 21st century B.C.E., King [[Ur-Nammu]] acted as the first legislator and created a formal system in thirty-two articles: the ''[[Code of Ur-Nammu]]''.<ref>Kramer, Samuel Noah. (1971) ''The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character,'' p.4, University of Chicago ISBN 0-226-45238-7</ref> Another important ancient code was the [[Code Hammurabi]], which formed the core of [[Babylonian law]]. Neither set of laws separated penal codes and civil laws. | ||

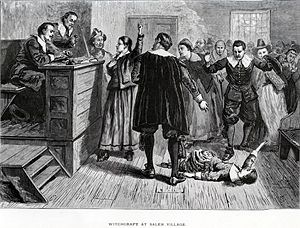

| + | [[Image:SalemWitchcraftTrial.jpg|thumb|left|A depiction of a 1600s criminal [[trial]], for [[witchcraft]] in [[Salem witch trials|Salem]]]] | ||

| + | The similarly significant Commentaries of Gaius on the [[Twelve Tables]] also conflated the civil and criminal aspects, treating theft or ''furtum'' as a [[tort]]. Assault and violent [[robbery]] were analogized to [[trespass]] as to property. Breach of such laws created an obligation of law or ''vinculum juris'' discharged by payment of monetary compensation or [[damages]]. | ||

| − | + | The first signs of the modern distinction between crimes and civil matters emerged during the [[William the Conqueror|Norman Invasion]] of England.<ref>see, Pennington, Kenneth (1993) ''The Prince and the Law, 1200–1600: Sovereignty and Rights in the Western Legal Tradition,'' University of California Press</ref> The special notion of criminal penalty, at least concerning Europe, arose in Spanish Late Scolasticism (see [[Alfonso de Castro]], when the theological notion of God's penalty (poena aeterna) that was inflicted solely for a guilty mind, became transfused into canon law first and, finally, to secular criminal law.<ref>Harald Maihold, ''Strafe für fremde Schuld? Die Systematisierung des Strafbegriffs in der Spanischen Spätscholastik und Naturrechtslehre'', Köln u.a. 2005</ref> The development of the [[state]] dispensing [[justice]] in a court clearly emerged in the eighteenth century when European countries began maintaining police services. From this point, criminal law had formal the mechanisms for enforcement, which allowed for its development as a discernable entity. | |

| − | + | ==Criminal Sanctions== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Criminal law is distinctive for the uniquely serious potential consequences of failure to abide by its rules. [[capital punishment|Capital punishment]] may be imposed in some jurisdictions for the most serious crimes. Physical or [[corporal punishment]] may be imposed such as [[Flagellation|whipping]] or [[caning]], although these punishments are prohibited in much of the world. Individuals may be [[incarcerated]] in [[prison]] or [[jail]] in a variety of conditions depending on the jurisdiction. Confinement may be solitary. Length of incarceration may vary from a day to life. Government supervision may be imposed, including [[house arrest]], and convicts may be required to conform to particularized guidelines as part of a [[parole]] or [[probation]] regimen. [[Fine]]s also may be imposed, seizing money or property from a person convicted of a crime. | |

| − | Criminal law in the [[ | ||

| − | + | Five objectives are widely accepted for enforcement of the criminal law by [[criminal punishment|punishments]]: [[Retributive justice|retribution]], [[deterrence (legal)|deterrence]], [[incapacitation]], [[rehabilitation (penology)|rehabilitation]] and [[restitution]]. Jurisdictions differ on the value to be placed on each. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *'''[[Retributive justice|Retribution]]''' - Criminals ought to ''suffer'' in some way. This is the most widely seen goal. Criminals have taken improper advantage, or inflicted unfair detriment, upon others and consequently, the criminal law will put criminals at some unpleasant disadvantage to "balance the scales." This belief has some connection with [[utilitarianism]]. People submit to the law to receive the right not to be murdered and if people contravene these laws, they surrender the rights granted to them by the law. Thus, one who murders may be murdered himself. A related theoryincludes the idea of "righting the balance." | |

| − | + | *'''[[Deterrence (legal)|Deterrence]]''' - ''Individual'' deterrence is aimed toward the specific offender. The aim is to impose a sufficient penalty to discourage the offender from criminal behavior. ''General'' deterrence aims at society at large. By imposing a penalty on those who commit offenses, other individuals are discouraged from committing those offenses. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *'''[[Incapacitation]]''' - Designed simply to keep criminals ''away'' from society so that the public is protected from their misconduct. This is often achieved through [[prison]] sentences today. The [[death penalty]] or [[banishment]] have served the same purpose. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *'''[[Rehabilitation]]''' - Aims at transforming an offender into a valuable member of society. Its primary goal is to prevent further offending by convincing the offender that their conduct was wrong. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | *'''[[Restitution]]''' - This is a victim-oriented theory of punishment. The goal is to repair, through state authority, any hurt inflicted on the victim by the offender. For example, one who [[embezzle]]s will be required to repay the amount improperly acquired. Restitution is commonly combined with other main goals of criminal justice and is closely related to concepts in the [[Civil law (common law)|civil law]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | ===The | + | ==Criminal law jurisdictions== |

| − | In defense, the | + | ===International law=== |

| + | {{main|International criminal law|Crimes against humanity|United States and the International Criminal Court}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Internationaal Strafhof.jpg|thumb|right|[[International Criminal Court]] in [[The Hague]]]] | ||

| + | [[Public international law]] deals extensively and increasingly with criminal conduct, that is heinous and ghastly enough to affect entire societies and regions. The formative source of modern international criminal law was the [[Nuremberg trials]] following the [[Second World War]] in which the leaders of [[Nazism]] were prosecuted for their part in [[genocide]] and [[atrocities]] across Europe. In 1998 an [[International criminal court]] was established in the [[Hague]] under what is known as the [[Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court|Rome Statute]]. This is specifically to try heads and members of governments who have taken part in [[crimes against humanity]]. Not all countries have agreed to take part, including [[Yemen]], [[Libya]], [[Iraq]] and the [[United States and the International Criminal Court|United States]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===United States=== | ||

| + | {{main|Criminal procedure}} | ||

| + | In the [[United States]], criminal prosecutions typically are initiated by [[complaint]] issued by a judge or by [[indictment]] issued by a grand jury. As to [[felonies]] in Federal court, the [[Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution]] requires [[indictment]]. The Federal requirement does not apply to the states, which have a diversity of practices. Three states (Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Washington) and the District of Columbia do not use grand jury indictments at all. The [[Sixth Amendment]] guarantees a criminal defendant the right to a [[speedy trial|speedy]] and [[public trial]], in both state and Federal courts, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime was committed, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of Counsel for his defense. The interests of the state are represented by a prosecuting attorney. The defendant may defend himself ''pro se'', and may act as his own attorney, if desired. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the [[Model Penal Code]] and examination of Anglo-American common law. Crimes in the U.S. which are outlawed nearly universally, such as [[murder]] and [[rape]] are occasionally referred to as [[malum in se]], while other crimes reflecting society's social attitudes and morality, such as laws prohibiting use of [[cannabis (drug)|marijuana]] are referred to as [[malum prohibitum]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{section-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===United Kingdom=== | ||

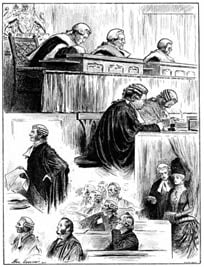

| + | [[Image:Oldbaileylondon-900.jpg|thumb|right|125px|The [[Old Bailey]] is the highest court of criminal appeal in [[England]] and [[Wales]] before the [[House of Lords]]]] | ||

| + | Criminal law in the United Kingdom derives from a number of diverse sources. The definitions of the different acts that constitute criminal offences can be found in the common law (murder, manslaughter, conspiracy to defraud) as well as in thousands of independent and disparate statutes and more recently from supranational legal regimes such as the EU. As the law lacks the criminal codes that have been instituted in the United States and [[civil law (legal system)|civil law]] jurisdictions, there is no unifying thread to how crimes are defined, although there have been calls from the Law Commission for the situation to be remedied. Criminal trials are administered hierarchically, from magistrates' courts, through the [[Crown Court]]s and up to the [[High Court]]. Appeals are then made to the [[Court of Appeal]] and finally the [[House of Lords]] on matters of law. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Procedurally, offences are classified as indictable and summary offences; summary offences may be tried before a magistrate without a jury, while indictable offences are tried in a crown court before a jury. The distinction between the two is broadly between that of minor and serious offences. At common law crimes are classified as either [[treason]], [[felony]] or [[misdemeanor]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The way in which the criminal law is defined and understood in the United Kingdom is less exact than in the United States as there have been few official articulations on the subject. The body of criminal law is considerably more disorganised, thus finding any common thread to the law is very difficult. A consolidated [[English Criminal Code]] was drafted by the [[Law Commission]] in [[1989]] but, though codification has been debated since [[1818]], [[as of 2007]] has not been implemented. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Selected Criminal Laws== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many, many laws are enforced by threat of [[criminal punishment]], and their particulars may vary widely from place to place. The entire universe of criminal law is too vast to intelligently catalog. Nevertheless, the following are some of the more known aspects of the criminal law. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Elements=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The criminal law generally prohibits undesirable ''acts''. Thus, proof of a crime requires proof of some act. Scholars label this the requirement of an [[actus reus]] or ''guilty act''. Some crimes — particularly modern regulatory offenses — require no more, and they are known as [[strict liability]] offenses. Nevertheless, because of the potentially severe consequences of criminal conviction, judges at [[common law]] also sought proof of an ''intent'' to do some bad thing, the [[mens rea]] or ''guilty mind''. As to crimes of which both ''actus reus'' and ''mens rea'' are requirements, judges have concluded that the elements must be present at precisely the same moment and it is not enough that they occurred sequentially at different times. <ref>This is demonstrated by ''R v. Church'' [1966] 1 QB 59. Mr. Church had a fight with a woman which rendered her unconscious. He attempted to revive her, but gave up, believing her to be dead. He threw her, still alive, in a nearby river, where she [[drown]]ed. The court held that Mr. Church was not guilty of murder (because he did not ever desire to kill her), but was guilty of [[manslaughter]]. The "chain of events," his act of throwing her into the water and his desire to hit her, coincided. In this manner, it does not matter when a guilty mind and act coincide, as long as at some point they do. See also, ''Fagan v. Metropolitan Police Commissioner'' [1968] 3 All ER 442, where angry Mr Fagan wouldn't take his car off a policeman's foot</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Actus reus==== | ||

| + | {{main|Actus reus}} | ||

| + | [[Image:LCJ-Court-1886.jpg|right|thumb|An English court room in 1886, with [[Lord Chief Justice Coleridge]] presiding]] | ||

| + | ''Actus reus'' is [[Latin]] for "guilty act" and is the physical element of committing a crime. It may be accomplished by an action, by threat of action, or exceptionally, by an [[omission (criminal)|omission]] to act. For example, the act of ''A'' striking ''B'' might suffice, or a parent's failure to give food to a young child also may provide the actus reus for a crime. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where the actus reus is a ''failure'' to act, there must be a ''duty''. A duty can arise through [[contract]],<ref>''R v. Pittwood (1902) 19 TLR 37 - a railway worker who omitted to shut the crossing gates, convicted of manslaughter when someone was run over by a train</ref> a voluntary undertaking,<ref>e.g. the partner in ''Gibbons'' who was not a blood parent, but had assumed a duty of care</ref> a blood relation with whom one lives,<ref>''R v. Stone and Dobinson'' [1977] QB 354, where an ill tended sister named Fanny couldn't leave bed, was not cared for at all and literally rotted in her own filth. This is [[gross negligence]] [[manslaughter]].</ref> and occasionally through one's official position.<ref>''R v. Dytham'' [1979] QB 722, where a policeman on duty stood and watched three men kick another to death.</ref> Duty also can arise from one's own creation of a dangerous situation.<ref>''R v. Miller'' [1983] 1 All ER 978, a squatter flicked away a still lit [[cigarette]], which landed on a [[mattress]]. He failed to take action, and after the building had burned down, he was convicted of [[arson]]. He failed to correct the dangerous situation he created, as he was duty bound to do. See also, ''R v. Santana-Bermudez'' (2003) where a thug with a needle failed to tell a policewoman searching his pockets that he had one.</ref> Occasional sources of duties for bystanders to accidents in Europe and North America are [[good samaritan law]]s, which can criminalise failure to help someone in distress (e.g. a drowning child).<ref>On the other hand, it was held in the U.K. that switching off the life support of someone in a [[persistent vegetative state]] is an omission to act and not criminal. Since discontinuation of power is not a voluntary act, not grossly negligent, and is in the patient's best interests, no crime takes place. ''Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland'' [1993] 1 All ER 821</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | An actus reus may be nullified by an absence of [[Causation (law)|causation]]. For example, a crime involves harm to a person, the person's action must be the ''[[But for test|but for]]'' cause and ''[[proximate cause]]'' of the harm.<ref>e.g ''R v. Pagett'' [1983] Crim LR 393, where 'but for' the defendant using his pregnant girlfriend for a human shield from police fire, she would not have died. Pagget's conduct foreseeably procured the heavy police response.</ref> If more than one cause exists (e.g. harm comes at the hands of more than one culprit) the act must have "more than a slight or trifling link" to the harm.<ref>''R v. Kimsey'' [1996] Crim LR 35, where 2 girls were racing their cars dangerously and crashed. One died, but the other was found slightly at fault for her death and convicted.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Causation is not broken simply because a victim is particularly vulnerable. This is known as the [[thin skull rule]].<ref>e.g. ''[[R v. Blaue]]'' [1975] where a Jehovah's witness (who refuse blood transfusions on religious grounds) was stabbed and without accepting life saving treatment died.</ref> However, it may be broken by an intervening act (''novus actus interveniens'') of a third party, the victim's own conduct,<ref>e.g. ''R v. Williams'' [1992] where a hitchhiker who jumped from a car and died, apparently because the driver tried to steal his wallet, was a "daft" intervening act. c.f. ''R v. Roberts'' [1971] Crim LR 27, where a girl jumped from a speeding car to avoid sexual advances and was injured and ''R v. Majoram'' [2000] Crim LR 372 where thugs kicked in the victims door scared him to jumping from the window. These actions were foreseeable, creating liability for injuries.</ref> or another unpredictable event. A mistake in [[Medicine|medical]] treatment typically will not sever the chain, unless the mistakes are in themselves "so potent in causing death."<ref>per Beldam LJ, ''R v. Cheshire'' [1991] 3 All ER 670; see also, ''R v. Jordan'' [1956] 40 Cr App R 152, where a stab victim recovering well in hospital was given an antibiotic. The victim was allergic, but he was given it the next day too, and died. The hospital's actions intervened and absolved the defendant.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Mens rea==== | ||

| + | {{main|Mens rea}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Robin shoots with sir Guy by Louis Rhead 1912.png|thumb|right|The English fictional character [[Robin Hood]] had the ''mens rea'' for robbing the rich, despite his good [[Intention (law)|intentions]] of giving to the poor]] | ||

| + | ''Mens rea'' is another [[Latin]] phrase, meaning "guilty mind." A guilty mind means an [[Intention in English law|intention]] to commit some wrongful act. Intention under criminal law is separate from a person's [[Motive (law)|motive]]. If [[Robin Hood|Mr. Hood]] robs from rich [[Sheriff Nottingham|Mr. Nottingham]] because his motive is to give the money to poor [[Maid Marion|Mrs. Marion]], his "good intentions" do not change his ''criminal intention'' to commit [[robbery]].<ref>''R v. Mohan'' [1975] 2 All ER 193, intention defined as "a decision to bring about... [the ''actus reus''] no matter whether the accused desired that consequence of his act or not."</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | A lower threshold of ''mens rea'' is satisfied when a defendant recognises an act is dangerous but decides to commit it anyway. This is [[Recklessness (criminal)|recklessness]]. For instance, if ''C'' tears a gas meter from a wall to get the money inside, and knows this will let flammable gas escape into a neighbour's house, he could be liable for poisoning.<ref>c.f. ''R v. Cunningham'' [1957] 2 All ER 863, where the defendant did not realise, and was not liable; also ''R v. G and Another'' [http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200203/ldjudgmt/jd031016/g-1.htm [2003] UKHL 50]</ref> Courts often consider whether the actor did recognize the danger, or alternatively [[Is-ought problem|ought to]] have recognised a risk.<ref>previously in the U.K. under ''Metropolitan Police Commissioner v. Caldwell'' [1981] 1 All ER 961</ref> Of course, a requirement only that one ''ought'' to have recognized a danger (though he did not) is tantamount to erasing ''intent'' as a requirement. In this way, the importance of [[mens rea]] has been reduced in some areas of the criminal law. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Wrongfulness of intent also may vary the seriousness of an offense. A killing committed with specific intent to kill or with conscious recognition that [[death]] or [[Grievous bodily harm|serious bodily harm]] will result, would be murder, whereas a killing effected by reckless acts lacking such a consciousness could be manslaughter.<ref>''R v. Woolin'' [http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199798/ldjudgmt/jd980722/wool.htm [1998] 4 All ER 103]</ref> On the other hand, it matters not who is actually harmed through a defendant's actions. The doctrine of [[transferred intent|transferred malice]] means, for instance, that if a man intends to strike a person with his belt, but the belt bounces off and hits another, mens rea is transferred from the intended target to the person who actually was struck.<ref>''R v. Latimer'' (1886) 17 QBD 359; though for an entirely different offence, e.g. breaking a window, one cannot transfer malice, see ''R v. Pembliton'' (1874) LR 2 CCR 119</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Strict liability==== | ||

| + | {{main|Strict liability}} | ||

| + | Not all crimes require bad intent, and alternatively, the threshold of culpability required may be reduced. For example, it might be sufficient to show that a defendant acted [[negligence|negligently]], rather than [[intention (criminal)|intentionally]] or [[recklessness (criminal)|recklessly]]. In offences of [[absolute liability]], other than the prohibited act, it may not be necessary to show anything at all, even if the defendant would not normally be perceived to be at fault. Most strict liability offences are created by statute, and often they are the result of ambiguous drafting unless legislation explicitly names an offence as one of strict liability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Fatal offenses=== | ||

| + | {{main|Murder|Involuntary manslaughter|Voluntary manslaughter}} | ||

| + | A ''murder'', defined broadly, is an unlawful killing. Unlawful killing is probably the act most frequently targeted by the criminal law. In many [[jurisdictions]], the crime of murder is divided into various gradations of severity, e.g., murder in the ''first degree'', based on ''intent''. ''[[Malice]]'' is a required element of murder. Manslaughter is a lesser variety of killing committed in the absence of ''malice'', brought about by reasonable [[provocation]], or [[diminished capacity]]. [[Involuntary manslaughter|''Involuntary'' manslaughter]], where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness. | ||

| + | {{Section-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Personal offenses=== | ||

| + | {{main|Assault|Battery (crime)|Rape|Sexual abuse}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many criminal codes protect the physical integrity of the body. The crime of [[battery (crime)|battery]] is traditionally understood as an unlawful touching, although this does not include everyday knocks and jolts to which people silently consent as the result of presence in a crowd. Creating a fear of imminent battery is an [[assault]], and also may give rise to criminal liability. Non-consensual [[sexual intercourse|intercourse]], or [[rape]], is a particularly egregious form of battery. | ||

| + | {{Section-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Property offenses=== | ||

| + | {{main|Criminal damage|Theft|Robbery|Burglary}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Property often is protected by the criminal law. [[Trespass]]ing is unlawful entry onto the real property of another. Many criminal codes provide penalties for [[conversion]], [[embezzlement]], [[theft]], all of which involve deprivations of the value of property. [[Robbery]] is a theft by force. | ||

| + | {{Section-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Participatory offenses=== | ||

| + | {{main|Accomplice|Aid and abet|Inchoate offences}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some criminal codes criminalize association with a criminal venture or involvement in criminality that does not actually come to fruition. Some examples are aiding, abetting, [[conspiracy]], and attempt. | ||

| + | {{Section-stub}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Defenses=== | ||

| + | {{seealso|Category:Criminal defenses}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | There are a variety of conditions that will tend to negate elements of a crime (particularly the ''intent'' element) that are known as ''defenses.'' The label may be apt in jurisdictions where the ''accused'' may be assigned some ''burden'' before a [[tribunal]]. However, in many jurisdictions, the entire burden to prove a crime is on the ''government'', which also must prove the ''absence'' of these defenses, where implicated. In other words, in many jurisdictions the absence of these so-called ''defenses'' is treated as an element of the crime. So-called ''defenses'' may provide partial or total refuge from punishment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Insanity==== | ||

| + | {{main|Insanity defense|Mental disorder defence}} | ||

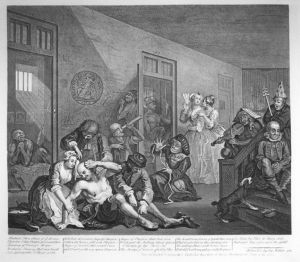

| + | [[Image:The Rake's Progress 8.jpg|left|thumb|[[William Hogarth]]'s ''[[A Rake's Progress]]'', depicting the world's oldest [[psychiatric hospital]], [[Bethlem Hospital]]]] | ||

| + | Insanity or ''mental disorder'' (Australia and Canada), may negate the ''intent'' of any crime, although it pertains only to those crimes having an ''intent'' element. A variety of rules have been advanced to define what, precisely, constitutes criminal ''insanity''. The most common definitions involve either an actor's lack of understanding of the wrongfulness of the offending conduct, or the actor's inability to conform conduct to the law.<ref>''[[M'Naghten's case]]'' [http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/1843/J16.html (1843) 10 C & F 200], where a man suffering extreme paranoia believed the [[Conservative Party (UK)|Tory party]] of the [[United Kingdom]], were persecuting him. He wanted to shoot and kill Prime Minister [[Sir Robert Peel]], but got Peel's secretary in the back instead. Mr M'Naghten was found to be insane, and instead of prison, put in a mental hospital. The case produced the [[M'Naghten rules|rules]] that a person is presumed to be sane and responsible, unless it is shown that (1) he was labouring under such a defect of reason (2) from disease of the mind (3) as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing, or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong. These elements must be proven present on the [[balance of probabilities]]. "Defect of reason" means much more than, for instance, absent mindedness making a lady walk from a supermarket without paying for a jar of mincemeat. ''R v. Clarke'' [1972] 1 All ER 219, caused by diabetes and depression, but the lady pleaded guilty because she did not want to defend herself as insane. Her conviction was later quashed. A "disease of the mind" includes not just brain diseases, but any impairment "permanent or transient and intermittent" so long as it is not externally caused (e.g. by drugs) and it has some effect on one's mind. ''R v. Sullivan'' [1984] AC 156. So epilepsy can count, as can an artery problem causing temporary loss of consciousness (and a man to attack his wife with a hammer). ''R v. Kemp'' [1957] 1 QB 399. Diabetes may cause temporary "insanity" ''R v. Hennessy'' [1989] 2 All ER 9; though see ''R v. Quick'' [1973] and the automatism defence. and even sleep walking has been deemed "insane".''R v. Burgess'' [1991] 2 All ER 769 "Not knowing the nature or wrongness of an act" is the final threshold which confirms insanity as related to the act in question. In ''R v. Windle'' ''R v. Windle'' 1952 2 QB 826 a man helped his wife commit suicide by giving her a hundred [[aspirin]]. He was in fact mentally ill, but as he recognised what he did and that it was wrong by saying to [[police]] "I suppose they will hang me for this", he was found not insane and guilty of murder. Mr Windle was not hanged!</ref> If one succeeds in being declared "not guilty by reason of insanity," then the result frequently is treatment [[mental hospital]], although some jurisdictions provide the sentencing authority with flexibility.<ref>E.g. in the U.K. Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991, giving the judge discretion to impose hospitalisation, guardianship, supervision and treatment or discharge.</ref> As further described in [http://www.theblanchlawfirm.com][[criminal defense]] articles available online. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Automatism==== | ||

| + | {{main|Automatism (law)}} | ||

| + | Automatism is a state where the [[muscles]] act without any control by the mind, or with a lack of consciousness.<ref>''Bratty v. Attorney-General for Northern Ireland'' [1963] AC 386</ref> One may suddenly fall ill, into a dream like state as a result of post traumatic stress,<ref>''R v. T'' [1990] Crim LR 256</ref> or even be "attacked by a swarm of bees" and go into an automatic spell.<ref>see ''Kay v. Butterworth'' (1945) 61 TLR 452</ref> However to be classed as an "automaton" means there must have been a total destruction of voluntary control, which does not include a partial loss of consciousness as the result of driving for too long.<ref>''Attorney-General's Reference (No. 2 of 1992)'' [1993] 4 All ER 683</ref> Where the onset of loss of bodily control was blameworthy, e.g., the result of voluntary drug use, it may be a defense only to specific intent crimes.<ref>''R v. Hardie'' [1984] 1 WLR 64. Mr Hardie took his girlfriend's [[valium]], because she had just [[Relationship breakup|kicked him out]] and he was [[Depression|depressed]]. She encouraged him to take them, to make him feel better. But he got angry and set fire to the [[wardrobe]]. It was held that he should not be convicted of [[arson]] because he expected the valium to calm him down, and this was its normal effect.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Intoxication==== | ||

| + | {{main|Intoxication defence}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Michelangelo drunken Noah.jpg|right|thumb|''The Drunkenness of Noah'' by [[Michelangelo Buonarroti|Michelangelo]]]] | ||

| + | In some jurisdictions, intoxication may negate [[specific intent]], a particular kind of mens rea applicable only to some crimes. For example, lack of specific intent might reduce murder to manslaughter. ''Voluntary'' intoxication nevertheless often will provide basic intent, e.g., the intent required for manslaughter.<ref>''DPP v. Majewski'' [[1977]] AC 433, where M was drunk and drugged and attacked people in a pub. He had no defence to [[actual bodily harm]]. In ''R v. Sheehan and Moore'' two viciously drunken scoundrels threw [[petrol]] on a [[tramp]] and set [[fire]] to him. They got off for murder, but still went down for [[manslaughter]], since that is a crime of basic intent. Of course, it can well be the case that someone is not drunk enough to support any intoxication defence at all. ''R v. Gallagher'' [1963] AC 349.</ref> On the other hand, ''involuntarily'' intoxication, for example by punch spiked unforeseeably with alcohol, may give rise to no inference of basic intent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Mistake==== | ||

| + | {{main|Mistake (criminal law)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | "I made a mistake" is a defense in some jurisdictions if the mistake is about a fact and is genuine.<ref>''DPP v. Morgan and others'' [1976] AC 182, where an [[RAF]] man told three officers to have sex with his wife, and she would pretend to refuse just to be stimulating. They pleaded mistake, and the jury did not believe them.</ref> For example, a charge of battery on a police officer may be negated by genuine (and perhaps reasonable) mistake of fact that the person battered was a criminal and not an officer.<ref>''R v. Williams'' [1987] 3 All ER 411</ref> | ||

| + | [[Image:galahad.jpg|left|thumb|[[Sir Galahad]], a mediaeval [[hero]] displaying qualities that Lord Halisham thought everyone could display under duress]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Self defense==== | ||

| + | {{main|Self-defense (theory)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Self-defense is, in general, some reasonable action taken in protection of self. An act taken in self-defense often is not a crime at all; no punishment will be imposed. To qualify, any defensive force must be proportionate to the threat. Use of a firearm in response to a non-lethal threat is a typical example of disproportionate force. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Duress==== | ||

| + | {{main|Duress}} | ||

| + | One who is "under duress" is forced into an unlawful act. Duress can be a defense in many jurisdictions, although not for the most serious crimes of [[murder]], [[attempted murder]], being an accessory to murder<ref>c.f. ''DPP for Northern Ireland v. Lynch'' [1975] 1 All ER 913, the old English rule whereby duress was available for a secondary party to murder; see now ''R v. Howe'' [1987] 1 AC 417, where the defendant helped [[torture]], [[Sexual abuse|sexually abuse]] and [[strangling]].</ref> and in many countries, [[treason]].<ref>This strict rule has been upheld in relation to a sixteen year old boy told by his father to stab his mother. ''R v. Gotts'' [1992] 2 AC 412, convicted for attempted murder.</ref> The duress must involve the threat of imminent peril of death or serious injury, operating on the defendant's mind and overbearing his will.<ref>''R v. Abdul-Hussain'' [1999] Crim LR 570, where two Shiites escaped from persecution in Iraq by going to Sudan and hijacking a plane. The threat was not imminent but "hanging over them" so they were not convicted.</ref> Threats to third persons may qualify.<ref>E.g., family, ''R v. Martin'' [1989], close friends, or under certain circumstances, car passengers, ''R v. Conway'' [1988] 3 All ER 1025</ref> The defendant must reasonably believe the threat,<ref>n.b. this may differ to the state of mind in the case of mistake, where the only requirement is that one honestly believes something. Here it may need to be a "reasonable belief", see also ''R v. Hasan (formerly Z)'' [http://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKHL/2005/22.html [2005] UKHL 22]</ref> and there is no defense if "a sober person of reasonable firmness, sharing the characteristics of the accused" would have responded differently.<ref>''R v. Graham'' [1982], where duress was rejected</ref> Age, pregnancy, physical disability, mental illness, sexuality have been considered, although basic intelligence has been rejected as a criterion.<ref>''R v. Bowen'' [1996]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The accused must not have foregone some safe avenue of escape.<ref>''R v. Gill'' [1963], where someone told to steal a lorry could have raised the alarm; see also ''R v. Hudson and Taylor'' [1971] where two teenage girls were scared into perjuring, and not convicted because their age was relevant and police protection not always seen to be safe.</ref> The duress must have been an order to do something specific, so that one cannot be threatened with harm to repay money and then choose to rob a bank to repay it.<ref>''R v. Cole'' [1994] </ref> If one puts himself in a position where he could be threatened, duress may not be a viable defense.<ref>See ''R v. Sharp'' [1987]. But see ''R v. Shepherd'' [1987] </ref> | ||

==Criminal law and society== | ==Criminal law and society== | ||

Criminal law distinguishes crimes from civil wrongs such as [[tort]] or breach of [[contract]]. Criminal law has been seen as a system of regulating the behavior of individuals and groups in relation to societal norms whereas civil law is aimed primarily at the relationship between private individuals and their rights and obligations under the law. Although many [[ancient history|ancient]] legal systems did not clearly define a distinction between criminal and civil law, in England there was little difference until the codification of criminal law occurred in the late nineteenth century. In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the English common criminal law of [[1750]] (with some minor American modifications like the clarification of ''mens rea'' in the [[Model Penal Code]]). In civil cases, the [[Seventh Amendment]] guarantees a defendant a right to a jury trial in federal court, but that right does not apply to the states (in contrast with criminal cases). | Criminal law distinguishes crimes from civil wrongs such as [[tort]] or breach of [[contract]]. Criminal law has been seen as a system of regulating the behavior of individuals and groups in relation to societal norms whereas civil law is aimed primarily at the relationship between private individuals and their rights and obligations under the law. Although many [[ancient history|ancient]] legal systems did not clearly define a distinction between criminal and civil law, in England there was little difference until the codification of criminal law occurred in the late nineteenth century. In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the English common criminal law of [[1750]] (with some minor American modifications like the clarification of ''mens rea'' in the [[Model Penal Code]]). In civil cases, the [[Seventh Amendment]] guarantees a defendant a right to a jury trial in federal court, but that right does not apply to the states (in contrast with criminal cases). | ||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <div class="references-small"> | ||

| + | {{reflist|3}} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Bergman, Paul; Berman-Barrett, Sara J., ''The criminal law handbook know your rights, survive the system'', Berkeley: Nolo Press, 2000. ISBN 0-585-10885-4 | * Bergman, Paul; Berman-Barrett, Sara J., ''The criminal law handbook know your rights, survive the system'', Berkeley: Nolo Press, 2000. ISBN 0-585-10885-4 | ||

| + | * Hall, Jerome, ''General Principles of Criminal Law'', Lexis Law Pub., 1960. ISBN 0-672-80035-7 | ||

* Katz, Leo; Moore, Michael S.; Morse, Stephen J., ''Foundations of criminal law'', NY: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-585-25201-7 | * Katz, Leo; Moore, Michael S.; Morse, Stephen J., ''Foundations of criminal law'', NY: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-585-25201-7 | ||

* Robinson, Paul H.; Cahill, Michael T., ''Law without justice: why criminal law doesn't give people what they deserve'', Oxford; NY: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-195-16015-0 | * Robinson, Paul H.; Cahill, Michael T., ''Law without justice: why criminal law doesn't give people what they deserve'', Oxford; NY: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-195-16015-0 | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/criminal-law/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Theories of Criminal Law] | + | * [http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/criminal-law/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Theories of Criminal Law] Retrieved September 26, 2007. |

| − | * [http://www.lawteacher.net/criminal.htm UK Criminal Law Guide] | + | * [http://www.lawteacher.net/criminal.htm UK Criminal Law Guide] Retrieved September 26, 2007. |

{{Credit1|Criminal_law|103476118|}} | {{Credit1|Criminal_law|103476118|}} | ||

Revision as of 18:23, 26 September 2007

The term criminal law, sometimes called penal law, refers to any of various bodies of rules in different jurisdictions whose common characteristic is the potential for unique and often severe impositions as punishment for failure to comply. Criminal punishment, depending on the offense and jurisdiction, may include execution, loss of liberty, government supervision (parole or probation), or fines. There are some archetypal crimes, like murder, but the acts that are forbidden are not wholly consistent between different criminal codes, and even within a particular code lines may be blurred as civil infractions may give rise also to criminal consequences. Criminal law typically is enforced by the government, unlike the civil law, which may be enforced by private parties.

Criminal law history

The first civilizations generally did not distinguish between civil and criminal law. The first known written codes of law were produced by the Sumerians. In the 21st century B.C.E., King Ur-Nammu acted as the first legislator and created a formal system in thirty-two articles: the Code of Ur-Nammu.[1] Another important ancient code was the Code Hammurabi, which formed the core of Babylonian law. Neither set of laws separated penal codes and civil laws.

The similarly significant Commentaries of Gaius on the Twelve Tables also conflated the civil and criminal aspects, treating theft or furtum as a tort. Assault and violent robbery were analogized to trespass as to property. Breach of such laws created an obligation of law or vinculum juris discharged by payment of monetary compensation or damages.

The first signs of the modern distinction between crimes and civil matters emerged during the Norman Invasion of England.[2] The special notion of criminal penalty, at least concerning Europe, arose in Spanish Late Scolasticism (see Alfonso de Castro, when the theological notion of God's penalty (poena aeterna) that was inflicted solely for a guilty mind, became transfused into canon law first and, finally, to secular criminal law.[3] The development of the state dispensing justice in a court clearly emerged in the eighteenth century when European countries began maintaining police services. From this point, criminal law had formal the mechanisms for enforcement, which allowed for its development as a discernable entity.

Criminal Sanctions

Criminal law is distinctive for the uniquely serious potential consequences of failure to abide by its rules. Capital punishment may be imposed in some jurisdictions for the most serious crimes. Physical or corporal punishment may be imposed such as whipping or caning, although these punishments are prohibited in much of the world. Individuals may be incarcerated in prison or jail in a variety of conditions depending on the jurisdiction. Confinement may be solitary. Length of incarceration may vary from a day to life. Government supervision may be imposed, including house arrest, and convicts may be required to conform to particularized guidelines as part of a parole or probation regimen. Fines also may be imposed, seizing money or property from a person convicted of a crime.

Five objectives are widely accepted for enforcement of the criminal law by punishments: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and restitution. Jurisdictions differ on the value to be placed on each.

- Retribution - Criminals ought to suffer in some way. This is the most widely seen goal. Criminals have taken improper advantage, or inflicted unfair detriment, upon others and consequently, the criminal law will put criminals at some unpleasant disadvantage to "balance the scales." This belief has some connection with utilitarianism. People submit to the law to receive the right not to be murdered and if people contravene these laws, they surrender the rights granted to them by the law. Thus, one who murders may be murdered himself. A related theoryincludes the idea of "righting the balance."

- Deterrence - Individual deterrence is aimed toward the specific offender. The aim is to impose a sufficient penalty to discourage the offender from criminal behavior. General deterrence aims at society at large. By imposing a penalty on those who commit offenses, other individuals are discouraged from committing those offenses.

- Incapacitation - Designed simply to keep criminals away from society so that the public is protected from their misconduct. This is often achieved through prison sentences today. The death penalty or banishment have served the same purpose.

- Rehabilitation - Aims at transforming an offender into a valuable member of society. Its primary goal is to prevent further offending by convincing the offender that their conduct was wrong.

- Restitution - This is a victim-oriented theory of punishment. The goal is to repair, through state authority, any hurt inflicted on the victim by the offender. For example, one who embezzles will be required to repay the amount improperly acquired. Restitution is commonly combined with other main goals of criminal justice and is closely related to concepts in the civil law.

Criminal law jurisdictions

International law

Public international law deals extensively and increasingly with criminal conduct, that is heinous and ghastly enough to affect entire societies and regions. The formative source of modern international criminal law was the Nuremberg trials following the Second World War in which the leaders of Nazism were prosecuted for their part in genocide and atrocities across Europe. In 1998 an International criminal court was established in the Hague under what is known as the Rome Statute. This is specifically to try heads and members of governments who have taken part in crimes against humanity. Not all countries have agreed to take part, including Yemen, Libya, Iraq and the United States.

United States

In the United States, criminal prosecutions typically are initiated by complaint issued by a judge or by indictment issued by a grand jury. As to felonies in Federal court, the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution requires indictment. The Federal requirement does not apply to the states, which have a diversity of practices. Three states (Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Washington) and the District of Columbia do not use grand jury indictments at all. The Sixth Amendment guarantees a criminal defendant the right to a speedy and public trial, in both state and Federal courts, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime was committed, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of Counsel for his defense. The interests of the state are represented by a prosecuting attorney. The defendant may defend himself pro se, and may act as his own attorney, if desired.

In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the Model Penal Code and examination of Anglo-American common law. Crimes in the U.S. which are outlawed nearly universally, such as murder and rape are occasionally referred to as malum in se, while other crimes reflecting society's social attitudes and morality, such as laws prohibiting use of marijuana are referred to as malum prohibitum.

United Kingdom

Criminal law in the United Kingdom derives from a number of diverse sources. The definitions of the different acts that constitute criminal offences can be found in the common law (murder, manslaughter, conspiracy to defraud) as well as in thousands of independent and disparate statutes and more recently from supranational legal regimes such as the EU. As the law lacks the criminal codes that have been instituted in the United States and civil law jurisdictions, there is no unifying thread to how crimes are defined, although there have been calls from the Law Commission for the situation to be remedied. Criminal trials are administered hierarchically, from magistrates' courts, through the Crown Courts and up to the High Court. Appeals are then made to the Court of Appeal and finally the House of Lords on matters of law.

Procedurally, offences are classified as indictable and summary offences; summary offences may be tried before a magistrate without a jury, while indictable offences are tried in a crown court before a jury. The distinction between the two is broadly between that of minor and serious offences. At common law crimes are classified as either treason, felony or misdemeanor.

The way in which the criminal law is defined and understood in the United Kingdom is less exact than in the United States as there have been few official articulations on the subject. The body of criminal law is considerably more disorganised, thus finding any common thread to the law is very difficult. A consolidated English Criminal Code was drafted by the Law Commission in 1989 but, though codification has been debated since 1818, as of 2007 has not been implemented.

Selected Criminal Laws

Many, many laws are enforced by threat of criminal punishment, and their particulars may vary widely from place to place. The entire universe of criminal law is too vast to intelligently catalog. Nevertheless, the following are some of the more known aspects of the criminal law.

Elements

The criminal law generally prohibits undesirable acts. Thus, proof of a crime requires proof of some act. Scholars label this the requirement of an actus reus or guilty act. Some crimes — particularly modern regulatory offenses — require no more, and they are known as strict liability offenses. Nevertheless, because of the potentially severe consequences of criminal conviction, judges at common law also sought proof of an intent to do some bad thing, the mens rea or guilty mind. As to crimes of which both actus reus and mens rea are requirements, judges have concluded that the elements must be present at precisely the same moment and it is not enough that they occurred sequentially at different times. [4]

Actus reus

Actus reus is Latin for "guilty act" and is the physical element of committing a crime. It may be accomplished by an action, by threat of action, or exceptionally, by an omission to act. For example, the act of A striking B might suffice, or a parent's failure to give food to a young child also may provide the actus reus for a crime.

Where the actus reus is a failure to act, there must be a duty. A duty can arise through contract,[5] a voluntary undertaking,[6] a blood relation with whom one lives,[7] and occasionally through one's official position.[8] Duty also can arise from one's own creation of a dangerous situation.[9] Occasional sources of duties for bystanders to accidents in Europe and North America are good samaritan laws, which can criminalise failure to help someone in distress (e.g. a drowning child).[10]

An actus reus may be nullified by an absence of causation. For example, a crime involves harm to a person, the person's action must be the but for cause and proximate cause of the harm.[11] If more than one cause exists (e.g. harm comes at the hands of more than one culprit) the act must have "more than a slight or trifling link" to the harm.[12]

Causation is not broken simply because a victim is particularly vulnerable. This is known as the thin skull rule.[13] However, it may be broken by an intervening act (novus actus interveniens) of a third party, the victim's own conduct,[14] or another unpredictable event. A mistake in medical treatment typically will not sever the chain, unless the mistakes are in themselves "so potent in causing death."[15]

Mens rea

Mens rea is another Latin phrase, meaning "guilty mind." A guilty mind means an intention to commit some wrongful act. Intention under criminal law is separate from a person's motive. If Mr. Hood robs from rich Mr. Nottingham because his motive is to give the money to poor Mrs. Marion, his "good intentions" do not change his criminal intention to commit robbery.[16]

A lower threshold of mens rea is satisfied when a defendant recognises an act is dangerous but decides to commit it anyway. This is recklessness. For instance, if C tears a gas meter from a wall to get the money inside, and knows this will let flammable gas escape into a neighbour's house, he could be liable for poisoning.[17] Courts often consider whether the actor did recognize the danger, or alternatively ought to have recognised a risk.[18] Of course, a requirement only that one ought to have recognized a danger (though he did not) is tantamount to erasing intent as a requirement. In this way, the importance of mens rea has been reduced in some areas of the criminal law.

Wrongfulness of intent also may vary the seriousness of an offense. A killing committed with specific intent to kill or with conscious recognition that death or serious bodily harm will result, would be murder, whereas a killing effected by reckless acts lacking such a consciousness could be manslaughter.[19] On the other hand, it matters not who is actually harmed through a defendant's actions. The doctrine of transferred malice means, for instance, that if a man intends to strike a person with his belt, but the belt bounces off and hits another, mens rea is transferred from the intended target to the person who actually was struck.[20]

Strict liability

Not all crimes require bad intent, and alternatively, the threshold of culpability required may be reduced. For example, it might be sufficient to show that a defendant acted negligently, rather than intentionally or recklessly. In offences of absolute liability, other than the prohibited act, it may not be necessary to show anything at all, even if the defendant would not normally be perceived to be at fault. Most strict liability offences are created by statute, and often they are the result of ambiguous drafting unless legislation explicitly names an offence as one of strict liability.

Fatal offenses

A murder, defined broadly, is an unlawful killing. Unlawful killing is probably the act most frequently targeted by the criminal law. In many jurisdictions, the crime of murder is divided into various gradations of severity, e.g., murder in the first degree, based on intent. Malice is a required element of murder. Manslaughter is a lesser variety of killing committed in the absence of malice, brought about by reasonable provocation, or diminished capacity. Involuntary manslaughter, where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness.

Personal offenses

Many criminal codes protect the physical integrity of the body. The crime of battery is traditionally understood as an unlawful touching, although this does not include everyday knocks and jolts to which people silently consent as the result of presence in a crowd. Creating a fear of imminent battery is an assault, and also may give rise to criminal liability. Non-consensual intercourse, or rape, is a particularly egregious form of battery.

Property offenses

Property often is protected by the criminal law. Trespassing is unlawful entry onto the real property of another. Many criminal codes provide penalties for conversion, embezzlement, theft, all of which involve deprivations of the value of property. Robbery is a theft by force.

Participatory offenses

Some criminal codes criminalize association with a criminal venture or involvement in criminality that does not actually come to fruition. Some examples are aiding, abetting, conspiracy, and attempt.

Defenses

There are a variety of conditions that will tend to negate elements of a crime (particularly the intent element) that are known as defenses. The label may be apt in jurisdictions where the accused may be assigned some burden before a tribunal. However, in many jurisdictions, the entire burden to prove a crime is on the government, which also must prove the absence of these defenses, where implicated. In other words, in many jurisdictions the absence of these so-called defenses is treated as an element of the crime. So-called defenses may provide partial or total refuge from punishment.

Insanity

Insanity or mental disorder (Australia and Canada), may negate the intent of any crime, although it pertains only to those crimes having an intent element. A variety of rules have been advanced to define what, precisely, constitutes criminal insanity. The most common definitions involve either an actor's lack of understanding of the wrongfulness of the offending conduct, or the actor's inability to conform conduct to the law.[21] If one succeeds in being declared "not guilty by reason of insanity," then the result frequently is treatment mental hospital, although some jurisdictions provide the sentencing authority with flexibility.[22] As further described in [1]criminal defense articles available online.

Automatism

Automatism is a state where the muscles act without any control by the mind, or with a lack of consciousness.[23] One may suddenly fall ill, into a dream like state as a result of post traumatic stress,[24] or even be "attacked by a swarm of bees" and go into an automatic spell.[25] However to be classed as an "automaton" means there must have been a total destruction of voluntary control, which does not include a partial loss of consciousness as the result of driving for too long.[26] Where the onset of loss of bodily control was blameworthy, e.g., the result of voluntary drug use, it may be a defense only to specific intent crimes.[27]

Intoxication

In some jurisdictions, intoxication may negate specific intent, a particular kind of mens rea applicable only to some crimes. For example, lack of specific intent might reduce murder to manslaughter. Voluntary intoxication nevertheless often will provide basic intent, e.g., the intent required for manslaughter.[28] On the other hand, involuntarily intoxication, for example by punch spiked unforeseeably with alcohol, may give rise to no inference of basic intent.

Mistake

"I made a mistake" is a defense in some jurisdictions if the mistake is about a fact and is genuine.[29] For example, a charge of battery on a police officer may be negated by genuine (and perhaps reasonable) mistake of fact that the person battered was a criminal and not an officer.[30]

Self defense

Self-defense is, in general, some reasonable action taken in protection of self. An act taken in self-defense often is not a crime at all; no punishment will be imposed. To qualify, any defensive force must be proportionate to the threat. Use of a firearm in response to a non-lethal threat is a typical example of disproportionate force.

Duress

One who is "under duress" is forced into an unlawful act. Duress can be a defense in many jurisdictions, although not for the most serious crimes of murder, attempted murder, being an accessory to murder[31] and in many countries, treason.[32] The duress must involve the threat of imminent peril of death or serious injury, operating on the defendant's mind and overbearing his will.[33] Threats to third persons may qualify.[34] The defendant must reasonably believe the threat,[35] and there is no defense if "a sober person of reasonable firmness, sharing the characteristics of the accused" would have responded differently.[36] Age, pregnancy, physical disability, mental illness, sexuality have been considered, although basic intelligence has been rejected as a criterion.[37]

The accused must not have foregone some safe avenue of escape.[38] The duress must have been an order to do something specific, so that one cannot be threatened with harm to repay money and then choose to rob a bank to repay it.[39] If one puts himself in a position where he could be threatened, duress may not be a viable defense.[40]

Criminal law and society

Criminal law distinguishes crimes from civil wrongs such as tort or breach of contract. Criminal law has been seen as a system of regulating the behavior of individuals and groups in relation to societal norms whereas civil law is aimed primarily at the relationship between private individuals and their rights and obligations under the law. Although many ancient legal systems did not clearly define a distinction between criminal and civil law, in England there was little difference until the codification of criminal law occurred in the late nineteenth century. In most U.S. law schools, the basic course in criminal law is based upon the English common criminal law of 1750 (with some minor American modifications like the clarification of mens rea in the Model Penal Code). In civil cases, the Seventh Amendment guarantees a defendant a right to a jury trial in federal court, but that right does not apply to the states (in contrast with criminal cases).

Notes

- ↑ Kramer, Samuel Noah. (1971) The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character, p.4, University of Chicago ISBN 0-226-45238-7

- ↑ see, Pennington, Kenneth (1993) The Prince and the Law, 1200–1600: Sovereignty and Rights in the Western Legal Tradition, University of California Press

- ↑ Harald Maihold, Strafe für fremde Schuld? Die Systematisierung des Strafbegriffs in der Spanischen Spätscholastik und Naturrechtslehre, Köln u.a. 2005

- ↑ This is demonstrated by R v. Church [1966] 1 QB 59. Mr. Church had a fight with a woman which rendered her unconscious. He attempted to revive her, but gave up, believing her to be dead. He threw her, still alive, in a nearby river, where she drowned. The court held that Mr. Church was not guilty of murder (because he did not ever desire to kill her), but was guilty of manslaughter. The "chain of events," his act of throwing her into the water and his desire to hit her, coincided. In this manner, it does not matter when a guilty mind and act coincide, as long as at some point they do. See also, Fagan v. Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1968] 3 All ER 442, where angry Mr Fagan wouldn't take his car off a policeman's foot

- ↑ R v. Pittwood (1902) 19 TLR 37 - a railway worker who omitted to shut the crossing gates, convicted of manslaughter when someone was run over by a train

- ↑ e.g. the partner in Gibbons who was not a blood parent, but had assumed a duty of care

- ↑ R v. Stone and Dobinson [1977] QB 354, where an ill tended sister named Fanny couldn't leave bed, was not cared for at all and literally rotted in her own filth. This is gross negligence manslaughter.

- ↑ R v. Dytham [1979] QB 722, where a policeman on duty stood and watched three men kick another to death.

- ↑ R v. Miller [1983] 1 All ER 978, a squatter flicked away a still lit cigarette, which landed on a mattress. He failed to take action, and after the building had burned down, he was convicted of arson. He failed to correct the dangerous situation he created, as he was duty bound to do. See also, R v. Santana-Bermudez (2003) where a thug with a needle failed to tell a policewoman searching his pockets that he had one.

- ↑ On the other hand, it was held in the U.K. that switching off the life support of someone in a persistent vegetative state is an omission to act and not criminal. Since discontinuation of power is not a voluntary act, not grossly negligent, and is in the patient's best interests, no crime takes place. Airedale NHS Trust v. Bland [1993] 1 All ER 821

- ↑ e.g R v. Pagett [1983] Crim LR 393, where 'but for' the defendant using his pregnant girlfriend for a human shield from police fire, she would not have died. Pagget's conduct foreseeably procured the heavy police response.

- ↑ R v. Kimsey [1996] Crim LR 35, where 2 girls were racing their cars dangerously and crashed. One died, but the other was found slightly at fault for her death and convicted.

- ↑ e.g. R v. Blaue [1975] where a Jehovah's witness (who refuse blood transfusions on religious grounds) was stabbed and without accepting life saving treatment died.

- ↑ e.g. R v. Williams [1992] where a hitchhiker who jumped from a car and died, apparently because the driver tried to steal his wallet, was a "daft" intervening act. c.f. R v. Roberts [1971] Crim LR 27, where a girl jumped from a speeding car to avoid sexual advances and was injured and R v. Majoram [2000] Crim LR 372 where thugs kicked in the victims door scared him to jumping from the window. These actions were foreseeable, creating liability for injuries.

- ↑ per Beldam LJ, R v. Cheshire [1991] 3 All ER 670; see also, R v. Jordan [1956] 40 Cr App R 152, where a stab victim recovering well in hospital was given an antibiotic. The victim was allergic, but he was given it the next day too, and died. The hospital's actions intervened and absolved the defendant.

- ↑ R v. Mohan [1975] 2 All ER 193, intention defined as "a decision to bring about... [the actus reus] no matter whether the accused desired that consequence of his act or not."

- ↑ c.f. R v. Cunningham [1957] 2 All ER 863, where the defendant did not realise, and was not liable; also R v. G and Another [2003 UKHL 50]

- ↑ previously in the U.K. under Metropolitan Police Commissioner v. Caldwell [1981] 1 All ER 961

- ↑ R v. Woolin [1998 4 All ER 103]

- ↑ R v. Latimer (1886) 17 QBD 359; though for an entirely different offence, e.g. breaking a window, one cannot transfer malice, see R v. Pembliton (1874) LR 2 CCR 119

- ↑ M'Naghten's case (1843) 10 C & F 200, where a man suffering extreme paranoia believed the Tory party of the United Kingdom, were persecuting him. He wanted to shoot and kill Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, but got Peel's secretary in the back instead. Mr M'Naghten was found to be insane, and instead of prison, put in a mental hospital. The case produced the rules that a person is presumed to be sane and responsible, unless it is shown that (1) he was labouring under such a defect of reason (2) from disease of the mind (3) as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing, or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong. These elements must be proven present on the balance of probabilities. "Defect of reason" means much more than, for instance, absent mindedness making a lady walk from a supermarket without paying for a jar of mincemeat. R v. Clarke [1972] 1 All ER 219, caused by diabetes and depression, but the lady pleaded guilty because she did not want to defend herself as insane. Her conviction was later quashed. A "disease of the mind" includes not just brain diseases, but any impairment "permanent or transient and intermittent" so long as it is not externally caused (e.g. by drugs) and it has some effect on one's mind. R v. Sullivan [1984] AC 156. So epilepsy can count, as can an artery problem causing temporary loss of consciousness (and a man to attack his wife with a hammer). R v. Kemp [1957] 1 QB 399. Diabetes may cause temporary "insanity" R v. Hennessy [1989] 2 All ER 9; though see R v. Quick [1973] and the automatism defence. and even sleep walking has been deemed "insane".R v. Burgess [1991] 2 All ER 769 "Not knowing the nature or wrongness of an act" is the final threshold which confirms insanity as related to the act in question. In R v. Windle R v. Windle 1952 2 QB 826 a man helped his wife commit suicide by giving her a hundred aspirin. He was in fact mentally ill, but as he recognised what he did and that it was wrong by saying to police "I suppose they will hang me for this", he was found not insane and guilty of murder. Mr Windle was not hanged!

- ↑ E.g. in the U.K. Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991, giving the judge discretion to impose hospitalisation, guardianship, supervision and treatment or discharge.

- ↑ Bratty v. Attorney-General for Northern Ireland [1963] AC 386

- ↑ R v. T [1990] Crim LR 256

- ↑ see Kay v. Butterworth (1945) 61 TLR 452

- ↑ Attorney-General's Reference (No. 2 of 1992) [1993] 4 All ER 683

- ↑ R v. Hardie [1984] 1 WLR 64. Mr Hardie took his girlfriend's valium, because she had just kicked him out and he was depressed. She encouraged him to take them, to make him feel better. But he got angry and set fire to the wardrobe. It was held that he should not be convicted of arson because he expected the valium to calm him down, and this was its normal effect.

- ↑ DPP v. Majewski 1977 AC 433, where M was drunk and drugged and attacked people in a pub. He had no defence to actual bodily harm. In R v. Sheehan and Moore two viciously drunken scoundrels threw petrol on a tramp and set fire to him. They got off for murder, but still went down for manslaughter, since that is a crime of basic intent. Of course, it can well be the case that someone is not drunk enough to support any intoxication defence at all. R v. Gallagher [1963] AC 349.

- ↑ DPP v. Morgan and others [1976] AC 182, where an RAF man told three officers to have sex with his wife, and she would pretend to refuse just to be stimulating. They pleaded mistake, and the jury did not believe them.

- ↑ R v. Williams [1987] 3 All ER 411

- ↑ c.f. DPP for Northern Ireland v. Lynch [1975] 1 All ER 913, the old English rule whereby duress was available for a secondary party to murder; see now R v. Howe [1987] 1 AC 417, where the defendant helped torture, sexually abuse and strangling.

- ↑ This strict rule has been upheld in relation to a sixteen year old boy told by his father to stab his mother. R v. Gotts [1992] 2 AC 412, convicted for attempted murder.

- ↑ R v. Abdul-Hussain [1999] Crim LR 570, where two Shiites escaped from persecution in Iraq by going to Sudan and hijacking a plane. The threat was not imminent but "hanging over them" so they were not convicted.

- ↑ E.g., family, R v. Martin [1989], close friends, or under certain circumstances, car passengers, R v. Conway [1988] 3 All ER 1025

- ↑ n.b. this may differ to the state of mind in the case of mistake, where the only requirement is that one honestly believes something. Here it may need to be a "reasonable belief", see also R v. Hasan (formerly Z) [2005 UKHL 22]

- ↑ R v. Graham [1982], where duress was rejected

- ↑ R v. Bowen [1996]

- ↑ R v. Gill [1963], where someone told to steal a lorry could have raised the alarm; see also R v. Hudson and Taylor [1971] where two teenage girls were scared into perjuring, and not convicted because their age was relevant and police protection not always seen to be safe.

- ↑ R v. Cole [1994]

- ↑ See R v. Sharp [1987]. But see R v. Shepherd [1987]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bergman, Paul; Berman-Barrett, Sara J., The criminal law handbook know your rights, survive the system, Berkeley: Nolo Press, 2000. ISBN 0-585-10885-4

- Hall, Jerome, General Principles of Criminal Law, Lexis Law Pub., 1960. ISBN 0-672-80035-7

- Katz, Leo; Moore, Michael S.; Morse, Stephen J., Foundations of criminal law, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-585-25201-7

- Robinson, Paul H.; Cahill, Michael T., Law without justice: why criminal law doesn't give people what they deserve, Oxford; NY: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-195-16015-0

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Theories of Criminal Law Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- UK Criminal Law Guide Retrieved September 26, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.