Difference between revisions of "William Jennings Bryan" - New World Encyclopedia

(article ready, image(s) currently in article are ok to use) |

(import new version) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox_Congressman |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| name=William Jennings Bryan | | name=William Jennings Bryan | ||

| image=William_Jennings_Bryan.JPG | | image=William_Jennings_Bryan.JPG | ||

| office=United States Secretary of State | | office=United States Secretary of State | ||

| order= 41st | | order= 41st | ||

| − | | term_start=March 5, 1913 | + | | term_start=[[March 5]], [[1913]] |

| − | | term_end=June 9, 1915 | + | | term_end=[[June 9]], [[1915]] |

| + | | president=[[Woodrow Wilson]] | ||

| + | | deputy=[[Huntington Wilson]] (1913)<br>[[John E. Osborne]] (1913-1915) | ||

| predecessor=[[Philander C. Knox]] | | predecessor=[[Philander C. Knox]] | ||

| successor=[[Robert Lansing]] | | successor=[[Robert Lansing]] | ||

| − | | | + | | party_election2 = [[US Democratic Party|Democratic]]/[[Populist Party (United States)|Populist]] |

| − | | | + | | nominee2= [[United States presidential election, 1896|President of the United States]] |

| − | | | + | | term_start2= [[November 3]], [[1896]] |

| − | | | + | | runningmate2= [[Arthur Sewall]] (D)<br>[[Thomas E. Watson]] ([[United States Populist Party|P]]) |

| − | | | + | | opponent2= [[William McKinley]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|R]]). |

| − | | | + | | incumbent2= [[Grover Cleveland]] ([[United States Democratic Party|D]]) |

| + | | preceded2=[[Grover Cleveland]] (D) | ||

| + | | succeeded2=Himself <br>[[Wharton Barker]] (P) | ||

| + | | nominee3= [[United States presidential election, 1900|President of the United States]] | ||

| + | | term_start3= [[November 6]], [[1900]] | ||

| + | | runningmate3= [[Adlai E. Stevenson]] | ||

| + | | opponent3= [[William McKinley]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|R]]). | ||

| + | | incumbent3= [[William McKinley]] (R) | ||

| + | | preceded3=Himself | ||

| + | | succeeded3=[[Alton Brooks Parker]] | ||

| + | | nominee4= [[United States presidential election, 1908|President of the United States]] | ||

| + | | term_start4= [[November 3]], [[1908]] | ||

| + | | runningmate4= [[John W. Kern]] | ||

| + | | opponent4= [[William Howard Taft]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|R]]). | ||

| + | | incumbent4= [[Theodore Roosevelt]] (R) | ||

| + | | preceded4=[[Alton Brooks Parker]] | ||

| + | | succeeded4=[[Woodrow Wilson]] | ||

| + | | state5= [[Nebraska]] | ||

| + | | district5= [[Nebraska's 1st congressional district|1st]] | ||

| + | | term_start5= [[March 4]], [[1891]] | ||

| + | | term_end5= [[March 3]], [[1895]] | ||

| + | | predecessor5= [[William James Connell]] | ||

| + | | successor5= [[Jesse Burr Strode]] | ||

| birth_date={{birth date|1860|3|19|mf=y}} | | birth_date={{birth date|1860|3|19|mf=y}} | ||

| birth_place=[[Salem, Illinois]], [[United States|U.S.]] | | birth_place=[[Salem, Illinois]], [[United States|U.S.]] | ||

| Line 23: | Line 44: | ||

| party=[[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] | | party=[[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] | ||

| spouse=Mary Baird Bryan | | spouse=Mary Baird Bryan | ||

| + | | children=[[Ruth Bryan Owen]] | ||

| + | | alma_mater= [[Illinois College]], [[Northwestern University Law School]] | ||

| + | | profession=[[Politician]], [[Lawyer]] | ||

| religion=[[Presbyterian]] | | religion=[[Presbyterian]] | ||

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

| + | '''William Jennings Bryan''' ([[March 19]], [[1860]] – [[July 26]], [[1925]]) was the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] nominee for [[President of the United States]] in 1896, 1900 and 1908, a [[lawyer]], and the 41st United States [[Secretary of State]] under President Woodrow Wilson. One of the most popular speakers in American history, he was noted for a deep, commanding voice. Bryan was a devout [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian]], a supporter of popular democracy, a critic of banks and railroads, a leader of the [[silverite]] movement in the 1890s, a leading figure in the Democratic Party, a [[peace]] advocate, a [[prohibition]]ist, an opponent of [[Social Darwinism]], and one of the most prominent leaders of [[Populism]] in late 19th- and early 20th century. Because of his faith in the goodness and rightness of the common people, he was called "The Great Commoner." In the intensely fought [[United States presidential election, 1896|1896 election]] and [[United States presidential election, 1900|1900 election]], he was defeated by [[William McKinley]] but retained control of the [[History of the United States Democratic Party|Democratic Party]]. For presidential candidates, Bryan invented the national stumping tour. In his three presidential bids, he promoted [[Free Silver]] in 1896, [[anti-imperialism]] in 1900, and [[trust-busting]] in 1908, calling on Democrats, in cases where corporations are protected, to renounce states rights to fight the [[Trust (19th century)|trusts]] and big banks, and embrace [[Populism|populist ideas]]. President [[Woodrow Wilson]] appointed him [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] in 1913, but Wilson's handling of the ''[[RMS Lusitania|Lusitania]]'' crisis in 1915 caused Bryan to resign in protest. He was a strong supporter of [[Prohibition in the United States|Prohibition]] in the 1920s, but is probably best known for his crusade against [[Darwinism]], which culminated in the [[Scopes Trial]] in 1925. Five days after the case was decided, he died in his sleep. <ref>{{cite book | last = Hakim | first = Joy | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = War, Peace, and All That Jazz | publisher = Oxford University Press | date = 1995 | location = New York, New York | pages = 44-45 | url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 0-19-509514-6}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Background and early career: 1860–1896== | ||

| + | The son of Silas and Mary Ann Bryan, Bryan was born in the [[Little Egypt (region)|Little Egypt]] region of southern [[Illinois]] on [[March 19]], [[1860]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bryan's mother was a [[Methodist]] born of [[English people|English]] heritage <ref> Bryan, Williams Jennings; Mary Baird Bryan (2003) "Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan" Kessinger p. 22-26.</ref>. Mary Bryan joined the Salem Baptists in 1872, so Bryan attended Methodist services on Sunday morning, and in the afternoon, Baptist services. At this point, William began spending his Sunday afternoons at the [[Cumberland Presbyterian Church]]. At age fourteen in 1874, Bryan attended a [[Revival meeting|revival]], was baptized, and joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In later life, Bryan said the day of his baptism was the most important day in his life, but, at the time it caused little change in his daily routine. In favor of the larger [[Presbyterian Church in the United States of America]], Bryan left the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His father Silas Bryan, was born of [[Protestant]]-[[Irish people|Irish]] and [[English people|English]] stock in [[Virginia]]. (Asked when his family "dropped the the 'O'" from his surname he responded there never had been an "O".) <ref> | ||

| + | Bryan, Williams Jennings; Mary Baird Bryan (2003) "Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan" Kessinger p. 22-26.</ref> As a [[Jacksonian Democrat]], Silas won election to the [[Illinois State Senate]], where he worked among [[Abraham Lincoln]] and [[Stephen Douglas]]. The year of William Jennings Bryan's birth, Silas lost his seat but shortly won election to be a state circuit judge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The family moved to a {{convert|520|acre|km2|1|sing=on}} farm north of Salem in 1866, living in a ten-room house that was the envy of [[Marion County, Illinois|Marion County]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:William Jennings Bryan 2.jpg|thumb|left|200px|William Jennings Bryan as a younger man.]] | ||

| − | + | Until age ten, Bryan was home schooled, finding in the [[Bible]] and [[McGuffey Readers]] the views [[gambling]] and [[liquor]] are evil and sinful. To attend Whipple Academy, the academy attached to [[Illinois College]], 14-year-old Bryan was sent to [[Jacksonville, Illinois|Jacksonville]] in 1874. | |

| − | + | Following high school, he entered Illinois College and studied [[classics]], graduating as [[valedictorian]] in 1881. During his time at Illinois College, Bryan was a member of the Sigma Pi literary society. To study law at [[Northwestern University School of Law|Union Law College]], he moved to [[Chicago]]. While preparing for the [[bar exam]], he taught high school. While teaching, he eventually married pupil Mary Elizabeth Baird in 1884. They settled in Salem, Illinois, a young town with a population of two thousand. | |

| − | + | Mary became a lawyer and collaborated with him on all his speeches and writings. He practiced law in [[Jacksonville, IL|Jacksonville]] (1883–87), then moved to the boom city of [[Lincoln, Nebraska]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the Democratic landslide of 1890, Bryan was elected to Congress and reelected by 140 votes in 1892. He ran for the Senate in 1894, but was overwhelmed in the Republican landslide. | |

| − | |||

| − | In | + | In Bryan's first years in Lincoln, he traveled to [[Valentine, Nebraska]] on business where he met an aspiring young cattleman named [[James Dahlman]]. Over the next forty years they remained friends, with Dahlman carrying Nebraska for Bryan twice while he was state Democratic Party chairman. Even when Dahlman became closely associated with Omaha's vice elements, including the breweries, as the city's eight-term mayor, he and Bryan maintained a collegial relationship.<ref>Folsom, B.W. (1999) ''No More Free Markets Or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900-1924. Lexington Books. p 57-59.</ref> |

| − | + | ==First campaign for the White House: 1896== | |

| + | [[Image:Cross cartoon.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] satire on Bryan's [[Cross of gold speech|"Cross of Gold"]] speech.]] | ||

| − | + | At the [[1896 Democratic National Convention]], Bryan delivered a famous speech lambasting Eastern monied classes for supporting the [[gold standard]] at the expense of the average worker. The speech is known as the [[Cross of gold speech|"Cross of Gold" speech]]. | |

| − | + | Over the [[Bourbon Democrats]] who long controlled the party and supported incumbent conservative President [[Grover Cleveland]], the party's agrarian and silver factions voted for Bryan, giving him the nomination of the Democratic Party. At thirty six, Bryan was the youngest presidential nominee ever. | |

| − | In Bryan | + | In addition, Bryan formally received the nominations of the [[Populist Party (United States)|Populist Party]] and the [[Silver Republican Party]]. Without crossing party lines, voters from any party could vote for him. The Populists nominated him only once (in 1896); they refused to do so in previous and later elections mostly due to an incident that occurred during the 1896 election. |

| − | + | Along with nominating Bryan for president, for the [[Vice President of the United States|vice presidency]], the Populists nominated [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]] [[United States House of Representatives|Representative]] [[Thomas E. Watson]] in hope Bryan would choose Watson to be his Democratic running mate. However, Bryan chose [[Maine]] industrialist and politician [[Arthur Sewall]]. The Populist Party was greatly disappointed and thereafter paid little attention to him.{{Fact|date=May 2008}} | |

| − | [[Image: | + | ===General Election=== |

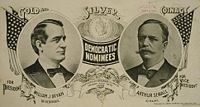

| + | [[Image:Bryan-Sewall.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Bryan/Sewall campaign poster.]] | ||

| − | + | On a program of prosperity through industrial growth, high tariffs and [[sound money]] (that is, gold.), the Republicans nominated [[William McKinley]]. Republicans ridiculed Bryan as a Populist. However, "Bryan's reform program was so similar to that of the Populists that he has often been mistaken for a Populist, but he remained a staunch Democrat throughout the Populist period."<ref> Coletta, (1964), vol.1, pg.40</ref> | |

| − | Bryan | + | Bryan demanded [[Bimetallism]] and "[[Free Silver]]" at a ratio of 16:1. Most leading Democratic newspapers rejected his candidacy. |

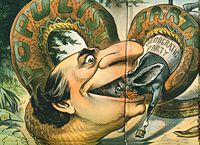

| − | [[Image:Bryan, Judge magazine, 1896.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:Bryan, Judge magazine, 1896.jpg|thumb|right|200px||Bryan as [[Populist Party (United States)|Populist]] swallowing the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]]; 1896 cartoon from the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] magazine ''Judge''.]] |

| − | + | Republicans discovered, by August, Bryan was solidly ahead in the South and West, but far behind in the Northeast. He appeared to be ahead in the Midwest, so the Republicans concentrated their efforts there. They said Bryan was a madman—a religious fanatic surrounded by anarchists—who would wreck the economy. {{Fact|date=May 2008}} By late September, the Republicans felt they were ahead in the decisive Midwest and began emphasizing that McKinley would bring prosperity to all Americans. McKinley scored solid gains among the middle classes, factory and railroad workers, prosperous farmers and among the [[German American]]s who rejected free silver. Bryan gave five hundred speeches in twenty seven states. William McKinley won by a margin of 271 to 176 in the [[United States Electoral College|electoral college]]. | |

==War and peace: 1898–1900== | ==War and peace: 1898–1900== | ||

| − | [[Image:1900Bryan.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[Image:1900Bryan.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Conservatives in 1900 ridiculed Bryan's eclectic platform.]] |

| − | + | ||

| + | Bryan volunteered for combat in the [[Spanish-American War|Spanish-American War in 1898]], arguing, "Universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force." Bryan became colonel of a Nebraska militia regiment; he spent the war in Florida and never saw combat. After the war, Bryan opposed the annexation of the [[Philippines]] (though he did support the [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Treaty of Paris]] that ended the war). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Presidential Election of 1900== | ||

| + | He ran as an anti-imperialist, finding himself in alliance with [[Andrew Carnegie]] and other millionaires. Republicans mocked Bryan as indecisive, or a coward; [[Henry Littlefield]] argued the portrayal of the [[Cowardly Lion]] in [[Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz|''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'']], published that year, reflected this. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bryan combined anti-imperialism with free silver, saying: | ||

| − | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights.<ref>Hibben, ''Peerless Leader,'' 220</ref></blockquote> | The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights.<ref>Hibben, ''Peerless Leader,'' 220</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | In a typical day he gave four hour-long speeches and shorter talks that added up to six hours of speaking. At an average rate of 175 words a minute, he turned out 63,000 words, enough to fill 52 columns of a newspaper. (No paper printed more than a column or two.) In Wisconsin, he once made 12 speeches in 15 hours.<ref>Coletta 1:272</ref>. He held his base in the South, but lost part of the West as McKinley retained the Northeast and Midwest and rolled up a landslide. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==On the Chautauqua circuit: 1900–1912== | |

| + | [[Image:WmJBryan-speech.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Bryan giving a speech during his 1908 run for the presidency.]] | ||

| − | + | Following his presidential bid, the forty year-old Bryan said he was letting politics obscure his calling as a [[Christian]].{{Fact|date=May 2008}} | |

| − | Following his | + | |

| + | For the next twenty five years, Bryan was the most popular Chautauqua speaker,{{Fact|date=May 2008}} delivering thousands of speeches, even while serving as secretary of state. He mostly spoke about religion but covered a wide variety of topics.{{Fact|date=May 2008}} His most popular lecture (and his personal favorite) was a lecture entitled "The Prince of Peace": in it, Bryan stressed religion was the solid foundation of morality, and individual and group morality was the foundation for peace and equality. Another famous lecture from this period, "The Value of an Ideal", was a stirring call to public service. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1905 speech, Bryan warned: "The [[Social Darwinism|Darwinian]] theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate - the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development." | ||

| − | [[Image:WJBryan-UticaNY-train.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[Image:WJBryan-UticaNY-train.jpg|thumb|left|200px|William Jennings Bryan addresses a crowd from a train in [[Utica, New York]], [[October 21]], [[1908]].]] |

| − | |||

| − | Bryan | + | Bryan threw himself into the work of the [[Social Gospel]]. Bryan served on organizations containing a large number of theological liberals: he sat on the [[Temperance movement|temperance]] committee of the [[Federal Council of Churches]] and on the general committee of the short-lived Interchurch World Movement. |

| − | + | Bryan founded a weekly magazine, ''The Commoner'', calling on Democrats to dissolve the trusts, regulate the railroads more tightly and support the [[Progressive Movement]]. He regarded prohibition as a "local" issue and did not endorse it until 1910. In London in 1906, he presented a plan to the Inter-Parliamentary Peace Conference for arbitration of disputes that he hoped would avert warfare. He tentatively called for nationalization of the railroads, then backtracked and called only for more regulation. His party nominated [[gold bug]] [[Alton B. Parker]] in [[United States presidential election, 1904|1904]], but Bryan was back in [[United States presidential election, 1908|1908]], losing this time to [[William Howard Taft]]. | |

| − | + | Bryan's speech to the students of [[Washington and Lee University]] began the [http://www.mockconforum.com/blog Washington & Lee Mock Convention]. | |

| − | Bryan's speech to the students of [[Washington and Lee University]] began the [http://www.mockconforum.com/blog Washington & Lee Mock Convention] | ||

==Secretary of State: 1913–1915== | ==Secretary of State: 1913–1915== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:WJB-fromthewarfront-1914.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Cartoon depicting [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]] Bryan reading news from the war fronts in 1914.]] | |

| + | |||

| + | For supporting [[Woodrow Wilson]] for the presidency in 1912, he was appointed as [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]].{{Fact|date=May 2008}} However, Wilson only nominally consulted Bryan and made all the major foreign policy decisions. Bryan negotiated twenty eight treaties that promised arbitration of disputes before war broke out between countries and the United States; onto which Germany never signed. In the civil war in Mexico in 1914, he supported American military intervention. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bryan resigned in June 1915 over Wilson's strong notes demanding "strict accountability for any infringement of [American] rights, intentional or incidental." He campaigned for Wilson's reelection in 1916. When war was declared in April 1917, Bryan wrote Wilson, "Believing it to be the duty of the citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the peril, I hereby tender my services to the Government. Please enroll me as a private whenever I am needed and assign me to any work that I can do."<ref>Hibben, Peerless Leader, p. 356</ref> Wilson, however, did not allow Bryan to rejoin the military and did not offer him any wartime role, so Bryan campaigned for the later adopted Constitutional amendments on [[Prohibition in the United States|prohibition]] and [[women's suffrage]]. | ||

==Prohibition battles: 1916–1925== | ==Prohibition battles: 1916–1925== | ||

| − | + | Partly to avoid Nebraska ethnics such as the German Americans who were "wet" and opposed to prohibition, <ref>(Coletta 3:116)</ref> Bryan moved to [[Miami]], [[Florida]]. Bryan filled lucrative speaking engagements and was extremely active in Christian organizations. Deeming him not dry enough, he refused to support the party's presidential nominee [[James M. Cox]] in 1920. As one biographer explains, | |

{{cquote|Bryan epitomized the prohibitionist viewpoint: Protestant and nativist, hostile to the corporation and the evils of urban civilization, devoted to personal regeneration and the social gospel, he sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic. Hence he became interested when its devotees in Nebraska viewed direct legislation as a means of obtaining antisaloon laws.<ref>Coletta vol 2 p. 8</ref>}} | {{cquote|Bryan epitomized the prohibitionist viewpoint: Protestant and nativist, hostile to the corporation and the evils of urban civilization, devoted to personal regeneration and the social gospel, he sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic. Hence he became interested when its devotees in Nebraska viewed direct legislation as a means of obtaining antisaloon laws.<ref>Coletta vol 2 p. 8</ref>}} | ||

| − | [[Image:WmJBryan+wife.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[Image:WmJBryan+wife.jpg|thumb|left|200px|William Jennings Bryan and wife, Mary, in [[New York City]], [[June 19]], [[1915]].]] |

| − | |||

| − | Bryan was the chief proponent of the [[Harrison Narcotics Tax Act]], the precursor to our modern [[War on Drugs]]. However, he argued | + | Bryans' national campaigning helped Congress pass the [[Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|18th Amendment]] in 1918, which shut down all saloons as of 1920. While prohibition was in effect, however, Bryan did not work to secure better enforcement. He ignored{{Fact|date=May 2008}} the [[Ku Klux Klan]], expecting it would soon fold. For the nomination in 1924, he opposed the wet [[Al Smith]] and his brother, [[Governor of Nebraska|Nebraska Governor]] [[Charles W. Bryan]], was put on the ticket with [[John W. Davis]] as candidate for [[Vice President of the United States|vice president]] to keep the Bryanites in line. Bryan was very close to his younger brother Charles and endorsed him for the vice presidency. |

| + | |||

| + | Bryan was the chief proponent of the [[Harrison Narcotics Tax Act]], the precursor to our modern [[War on Drugs]]. However, he argued for the act's passage more as an international obligation than on moral grounds.<ref> [http://www.historicaldocuments.com/HarrisonNarcoticsTaxAct.htm Historical documents] </ref> | ||

==Fighting Darwinism: 1918–1925== | ==Fighting Darwinism: 1918–1925== | ||

| − | + | Before World War I, Bryan believed moral progress could achieve equality at home and, in the international field, peace between all the world's nations. | |

| − | + | In his famous [[Chautauqua]] lecture, "The Prince of Peace," Bryan warned the theory of evolution could undermine the foundations of morality. However, he concluded, "While I do not accept the Darwinian theory I shall not quarrel with you about it." | |

| − | + | However, the [[First World War]] convinced Bryan that Darwinism undermined morality{{Fact|date=May 2008}} and moral progress had ground to a complete halt. | |

| − | [[Image:ChasW+WmJBryan.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:ChasW+WmJBryan.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Charles W. Bryan|Charles W.]] and William J. Bryan.]] |

| − | |||

| − | + | Bryan was heavily influenced by [[Vernon Kellogg]]'s 1917 book, ''Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in Belgium and France'',{{Fact|date=May 2008}} which forwarded that most German military leaders were committed Darwinists skeptical of Christianity, and ''The Science of Power'' by Benjamin Kidd (1918),{{Fact|date=May 2008}} which attributed the [[philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche]] to German nationalism, materialism, and militarism which in turn was the outworking of the Darwinian hypothesis. | |

| − | [[Image:EverHopeful-WmChasBryan-1924.jpg|thumb|left| | + | In 1920, Bryan told the [[World Brotherhood Congress]] Darwinism was "the most paralyzing influence with which civilization has had to deal in the last century" and that Nietzsche, in carrying Darwinism to its logical conclusion, "promulgated a philosophy that condemned democracy... denounced Christianity... denied the existence of God, overturned all concepts of morality... and endeavored to substitute the worship of the superhuman for the worship of Jehovah."{{Fact|date=May 2008}} |

| − | + | ||

| + | However, it was not until 1921 that Bryan saw Darwinism as a major internal threat to the US. The major study which seemed to convince Bryan of this was [[James H. Leuba]]'s ''The Belief in God and Immortality, a Psychological, Anthropological and Statistical Study'' (1916). In this study, Leuba shows during four years of college a considerable number of college students lost their faith. Bryan was horrified that the next generation of American leaders might have the degraded sense of morality which he believed had prevailed in Germany and caused the Great War. Bryan then launched an anti-evolution campaign. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:EverHopeful-WmChasBryan-1924.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''Ever Hopeful''<br/>A November 1924 cartoon depicts Bryan with his brother, [[Charles W. Bryan|Charles]], sitting on a log marked "Almost the [[Solid South]]" looking at the sun marked "1928" where more hope might come for them. Charles unsuccessfully ran for the [[Vice President of the United States|vice presidency]] in the [[United States presidential election, 1924|1924 election]] having lost a number of southern states.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | When [[Union Theological Seminary & Presbyterian School of Christian Education|Union Theological Seminary]] in Virginia invited Bryan to deliver the James Sprunt Lectures, the campaign kicked off in October 1921. The heart of the lectures was a lecture entitled "The Origin of Man", in which Bryan asked, "what is the role of man in the universe and what is the purpose of man?" For Bryan, the [[Bible]] was absolutely central to answering this question, and moral responsibility and the spirit of brotherhood could only rest on belief in God. | ||

The Sprunt lectures were published as ''In His Image'', and sold over 100,000 copies, while "The Origin of Man" was published separately as ''The Menace of Darwinism'' and also sold very well. | The Sprunt lectures were published as ''In His Image'', and sold over 100,000 copies, while "The Origin of Man" was published separately as ''The Menace of Darwinism'' and also sold very well. | ||

| Line 117: | Line 168: | ||

Bryan was worried that Darwinism was making grounds not only in the universities, but also within the church itself. Many colleges were still church-affiliated at this point. The developments of 19th century [[Liberal Christianity|liberal theology]], and [[higher criticism]] in particular, had left the door open to the point where many clergymen were willing to embrace Darwinism and claimed that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian [[Elder (religious)|elder]], decided to run for the position of [[Moderator of the General Assembly]] of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, which was at the time embroiled in the [[Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy]]. (Under [[presbyterian church governance]], clergy and laymen are equally represented in the General Assembly, and the post of Moderator is open to any member of General Assembly.) Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the [[College of Wooster]], who had loudly endorsed the teaching of Darwinism in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451-427. Bryan then failed in a proposal to cut off funds to schools where Darwinism was taught. Instead the General Assembly announced disapproval of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution. | Bryan was worried that Darwinism was making grounds not only in the universities, but also within the church itself. Many colleges were still church-affiliated at this point. The developments of 19th century [[Liberal Christianity|liberal theology]], and [[higher criticism]] in particular, had left the door open to the point where many clergymen were willing to embrace Darwinism and claimed that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian [[Elder (religious)|elder]], decided to run for the position of [[Moderator of the General Assembly]] of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, which was at the time embroiled in the [[Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy]]. (Under [[presbyterian church governance]], clergy and laymen are equally represented in the General Assembly, and the post of Moderator is open to any member of General Assembly.) Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the [[College of Wooster]], who had loudly endorsed the teaching of Darwinism in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451-427. Bryan then failed in a proposal to cut off funds to schools where Darwinism was taught. Instead the General Assembly announced disapproval of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution. | ||

| − | + | According to author Ronald L. Numbers, Bryan was not nearly as much of a [[fundamentalist]] as many modern day [[creationist]]s and is more accurately described as a "[[day-age creationist]].": | |

| − | :William Jennings Bryan, the much misunderstood leader of the post–World War I antievolution crusade, not only read the Mosaic “days” as geological “ages” but allowed for the possibility of organic | + | :William Jennings Bryan, the much misunderstood leader of the post–World War I antievolution crusade, not only read the Mosaic “days” as geological “ages” but allowed for the possibility of organic evolution— so long as it did not impinge on the supernatural origin of Adam and Eve.<ref name>[http://www.hup.harvard.edu/pdf/NUMCRX_excerpt.pdf ''The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design''], expanded edition, Ronald L. Numbers, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 2006, p. 13 ISBN-10: 0-674-02339-0</ref> |

| − | |||

===Scopes Trial: 1925=== | ===Scopes Trial: 1925=== | ||

| − | In addition to his unsuccessful advocacy of banning the teaching of evolution in church-run universities, Bryan also actively lobbied in favor of state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution. The legislatures of several southern states proved more receptive to his anti-evolution message than the Presbyterian Church had, and consequently passed laws banning the teaching of evolution in public schools after Bryan addressed them. A prominent example was the [[Butler Act]] of 1925, making it unlawful in Tennessee to teach that mankind evolved from lower life forms.<ref>"It shall be unlawful..." to teach "...any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." [http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/tennstat.htm Section 1 of House Bill No. 185] | + | [[Image:scopes trial.jpg|right|thumb|200px|[[Clarence Darrow]] and William Jennings Bryan chat in court during the [[Scopes Trial]].]] |

| + | In addition to his unsuccessful advocacy of banning the teaching of evolution in church-run universities, Bryan also actively lobbied in favor of state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution. The legislatures of several southern states proved more receptive to his anti-evolution message than the Presbyterian Church had, and consequently passed laws banning the teaching of evolution in public schools after Bryan addressed them. A prominent example was the [[Butler Act]] of 1925, making it unlawful in Tennessee to teach that mankind evolved from lower life forms.<ref>"It shall be unlawful..." to teach "...any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." [http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/scopes/tennstat.htm Section 1 of House Bill No. 185]</ref> | ||

| − | Bryan's participation in the highly publicized 1925 [[Scopes Trial]] served as a capstone to his career. He was asked by [[William Bell Riley]] to represent the [[World Christian Fundamentals Association]] as counsel at the trial. During the trial Bryan took the stand and was questioned by defense lawyer [[Clarence Darrow]] about his views on the Bible. Biologist [[Stephen Jay Gould]] has speculated that Bryan's antievolution views were a result of his Populist idealism and suggests that Bryan's fight was really against [[Social Darwinism]]. Others, such as biographer Michael Kazin, reject that conclusion based on Bryan's failure during the trial to attack the [[eugenics]] in the textbook, [[Civic Biology]].<ref>Kazin p.289</ref> The national media reported the trial in great detail, with [[H. L. Mencken]] using Bryan as a symbol of Southern ignorance and anti-intellectualism. | + | Bryan's participation in the highly publicized 1925 [[Scopes Trial]] served as a capstone to his career. He was asked by [[William Bell Riley]] to represent the [[World Christian Fundamentals Association]] as counsel at the trial. During the trial Bryan took the stand and was questioned by defense lawyer [[Clarence Darrow]] about his views on the Bible. Biologist [[Stephen Jay Gould]] has speculated that Bryan's antievolution views were a result of his Populist idealism and suggests that Bryan's fight was really against [[Social Darwinism]]. Others, such as biographer Michael Kazin, reject that conclusion based on Bryan's failure during the trial to attack the [[eugenics]] in the textbook, [[Civic Biology]].<ref>Kazin p.289</ref> The national media reported the trial in great detail, with [[H. L. Mencken]] using Bryan as a symbol of Southern ignorance and anti-intellectualism. In a more humorous vein, satirist [[Richard Armour (poet)|Richard Armour]] stated in ''It All Started With Columbus'' that Darrow had "made a monkey out of" Bryan. |

| − | + | The trial concluded with a directed verdict of guilty, which the defense encouraged, as their aim was to take the law itself to a higher court in order to challenge its constitutionality. | |

| + | |||

| + | Immediately after the trial, he continued to edit and deliver speeches, traveling hundreds of miles that week. On Sunday, [[July 26]] [[1925]], he drove from Chattanooga to Dayton to attend a church service, ate a meal and died in his sleep that afternoon—five days after the trial ended. School Superintendent Walter White proposed that Dayton should create a Christian college as a lasting memorial to Bryan; fund raising was successful and [[Bryan College]] opened in 1930. Bryan is buried in [[Arlington National Cemetery]]. His tombstone reads "He kept the Faith." He was survived by among others, a daughter, Congresswoman [[Ruth Bryan Owen]]. | ||

====Popular image==== | ====Popular image==== | ||

| − | The 1950s play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, ''[[Inherit the Wind]]'', is | + | {{main|Inherit the Wind}} |

| + | The 1950s play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, ''[[Inherit the Wind]]'', is a fictionalized account of the Scopes Trial written in response to [[McCarthyism]]. A populist thrice-defeated Presidential candidate from Nebraska named Matthew Harrison Brady comes to a small town named Hillsboro in the deep south to help prosecute a young teacher for teaching Darwin to his schoolchildren. He is opposed by a famous liberal lawyer, Henry Drummond, and chastised by a cynical newspaperman as the trial assumes a national profile. Critics of the play charge that it mischaracterizes Bryan and the trial. | ||

| − | Bryan also appears as a character in [[Douglas Moore]]'s 1956 opera, ''The Ballad of Baby Doe'' and is briefly mentioned in [[John Steinbeck]]'s ''[[East of Eden]]''. | + | Bryan also appears as a character in [[Douglas Moore]]'s 1956 opera, ''The Ballad of Baby Doe'' and is briefly mentioned in [[John Steinbeck]]'s ''[[East of Eden]]''. His death is referred to in [[Ernest Hemingway]]'s ''[[The Sun Also Rises]]''. Bryan was also mentioned on the [[May 23]], 2007 episode of ''[[The Daily Show]]'' when fictional comedian Geoffrey Foxworthington (an early 20th century parody of [[Jeff Foxworthy]]) quotes, "If your dream [[Vice President of the United States|Vice President]] is William Jennings Bryan, you might be a puzzlewit." In [[Robert A. Heinlein]]'s ''[[Job: A Comedy of Justice]]'', Bryan's unsuccessful or successful runs for the presidency are seen as the 'splitting off' events of the alternate histories through which the protagonists travel. |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | [[Image:WJB-Fairviewstatue.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Statue of Bryan outside his home "Fairview" in [[Lincoln, Nebraska]].]] | + | <!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:WJB-Fairviewstatue.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Statue of Bryan outside his home "Fairview" in [[Lincoln, Nebraska]].]] —> |

[[Image:williamjenningsbryanstatue.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Statue of Bryan on the lawn of the [[Rhea County, Tennessee]] courthouse in [[Dayton, Tennessee]].]] | [[Image:williamjenningsbryanstatue.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Statue of Bryan on the lawn of the [[Rhea County, Tennessee]] courthouse in [[Dayton, Tennessee]].]] | ||

| − | Kazin (2006) considers him the first of the 20th century "celebrity politicians" better known for their personalities and communications skills than their political views. | + | Kazin (2006) considers him the first of the 20th century "celebrity politicians" better known for their personalities and communications skills than their political views. Shannon Jones (2006) writes that one of the few topics touched on by historians is Bryan's apparent support of American racism, pointing that Bryan never took a principled stand against [[white supremacy]] in the [[Southern United States]]. Jones explains that "the ruling elite in the South, the remnants of the old southern slaveholding oligarchy, formed a critical base of the Democratic Party. This Party had defended slavery and secession and had led the struggle against post-[[American Civil War|Civil War]] [[Reconstruction era of the United States|Reconstruction]]. It had opposed granting suffrage to freed slaves and generally opposed all progressive reforms aimed at alleviating the oppression of blacks and poor whites. No politician could hope for national leadership in the Democratic Party, let alone expect to win the presidency, by attacking the system of racial oppression in the South." |

| + | |||

| + | [[Alan Wolfe]] has concluded that Bryan's "legacy remains complicated." Form and content mix uneasily in Bryan's politics. The content of his speeches leads in a direct line to the progressive reforms adopted by 20th century Democrats. But the form his actions took—-a romantic invocation of the American past, a populist insistence on the wisdom of ordinary folk, a faith-based insistence on sincerity and character. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In "[[They Also Ran]]", [[Irving Stone]] criticized Bryan as a person who was egocentric and never admitted wrong. Stone mentioned how Bryan lived a sheltered life and therefore could not feel the suffering of the common man. He speculated that Bryan merely acted as a champion of the common man in order to get their votes. Irving Stone mentioned that none of his ideas were original and that he did not have the brains to be an effective president. Stone personally believed Bryan to be one of the nation's worst Secretaries of State. He also feared that Bryan would have supported many radical religious [[blue laws]]. Stone felt that Bryan had one of the most undisciplined minds of the 19th century and that McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft all made better presidents. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Bryan County, Oklahoma]] was named after him.<ref name="okhs-bryan-county">Oklahoma Historical Society. [http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Chronicles/v002/v002p075.html "Origin of County Names in Oklahoma"], ''Chronicles of Oklahoma'' 2:1 (March 1924) 75-82 (retrieved August 18, 2006).</ref> |

| + | [[Bryan Memorial Hospital]] (now [https://www.bryanlgh.org/ BryanLGH Medical Center]) of Lincoln, Nebraska, and | ||

| + | [[Bryan College]] located in Dayton, Tennessee, are also named for William Jennings Bryan. | ||

| + | The [[William Jennings Bryan House]] in Nebraska was named a U.S. [[National Historic Landmark]] in 1963. | ||

| − | [[ | + | The full name of [[Baseball Hall of Fame]]r [[Billy Herman]] was William Jennings Bryan Herman. |

| − | === | + | ==Nicknames== |

| + | Bryan had an unusual number of nicknames given to him in his lifetime; most of these were given by his loyal admirers in the Democratic Party. In addition to his best-known nickname, "The Great Commoner", he was also called "The Silver Knight of the West" (due to his support of the [[free silver]] issue) and the "Boy Orator of the [[Platte]]" (a reference to his oratorical skills and his home near the [[Platte River]] in Nebraska). A derisive nickname given by journalist [[H.L. Mencken]], a prominent Bryan critic, was "The Protestant Pope", a reference to Bryan's devout religious views. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Publications== | ||

| + | ===Secondary sources=== | ||

====Biographies==== | ====Biographies==== | ||

* Cherny, Robert W. ''A Righteous Cause: The Life of William Jennings Bryan'' (1994). | * Cherny, Robert W. ''A Righteous Cause: The Life of William Jennings Bryan'' (1994). | ||

| Line 163: | Line 228: | ||

* Mahan, Russell L. "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896" ''White House Studies'' 2003 3(2): 215-227. {{ISSN|1535-4768}} | * Mahan, Russell L. "William Jennings Bryan and the Presidential Campaign of 1896" ''White House Studies'' 2003 3(2): 215-227. {{ISSN|1535-4768}} | ||

* Murphy, Troy A. "William Jennings Bryan: Boy Orator, Broken Man, and the 'Evolution' of America's Public Philosophy." ''Great Plains Quarterly'' 2002 22(2): 83-98. {{ISSN|0275-7664}} | * Murphy, Troy A. "William Jennings Bryan: Boy Orator, Broken Man, and the 'Evolution' of America's Public Philosophy." ''Great Plains Quarterly'' 2002 22(2): 83-98. {{ISSN|0275-7664}} | ||

| − | * [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723%28196606%2953%3A1%3C41%3AWJBATS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z | + | * Willard H. Smith. "William Jennings Bryan and the Social Gospel," ''The Journal of American History,'' Vol. 53, No. 1. (Jun., 1966), pp. 41-60. [http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8723%28196606%2953%3A1%3C41%3AWJBATS%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z in JSTOR] |

* Taylor, Jeff. ''Where Did the Party Go?: William Jennings Bryan, Hubert Humphrey, and the Jeffersonian Legacy'' (2006), on Bryan's place in Democratic Party history and ideology. | * Taylor, Jeff. ''Where Did the Party Go?: William Jennings Bryan, Hubert Humphrey, and the Jeffersonian Legacy'' (2006), on Bryan's place in Democratic Party history and ideology. | ||

* Wood, L. Maren. "The Monkey Trial Myth: Popular Culture Representations of the Scopes Trial" ''Canadian Review of American Studies'' 2002 32(2): 147-164. {{ISSN|0007-7720}} | * Wood, L. Maren. "The Monkey Trial Myth: Popular Culture Representations of the Scopes Trial" ''Canadian Review of American Studies'' 2002 32(2): 147-164. {{ISSN|0007-7720}} | ||

===Primary sources=== | ===Primary sources=== | ||

| + | {{Sound sample box align right|Speech sample}} | ||

| + | {{Listen | ||

| + | |filename=Bryan - The Ideal Republic.ogg | ||

| + | |title="The Ideal Republic" | ||

| + | |description=A speech given by Bryan in [[Richmond, Indiana]], 1922. | ||

| + | |format=[[Ogg]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Sample box end}} | ||

* Bryan, Mary Baird, ed. ''The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan'' (1925). | * Bryan, Mary Baird, ed. ''The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan'' (1925). | ||

* Bryan, William Jennings. ''[http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC30986706 The First Battle: A Story of the Campaign of 1896]'' (1897), speeches from 1896 campaign. | * Bryan, William Jennings. ''[http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC30986706 The First Battle: A Story of the Campaign of 1896]'' (1897), speeches from 1896 campaign. | ||

| Line 175: | Line 248: | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | * [[History of creationism]] | + | *[[History of creationism]] |

| − | * [[Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy]] | + | *[[Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy]] |

| − | * [[Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz]] | + | *[[Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz]] |

| − | * [[History of the United States Democratic Party]] | + | *[[History of the United States Democratic Party]] |

| − | * [[Progressive Movement]] | + | *[[Progressive Movement]] |

* U.S. presidential elections of [[United States presidential election, 1896|1896]], [[United States presidential election, 1900|1900]] and [[United States presidential election, 1908|1908]]. | * U.S. presidential elections of [[United States presidential election, 1896|1896]], [[United States presidential election, 1900|1900]] and [[United States presidential election, 1908|1908]]. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | |||

{{Commonscat}} | {{Commonscat}} | ||

{{wikiquote}} | {{wikiquote}} | ||

{{Wikisource author}} | {{Wikisource author}} | ||

{{CongBio|B000995}} | {{CongBio|B000995}} | ||

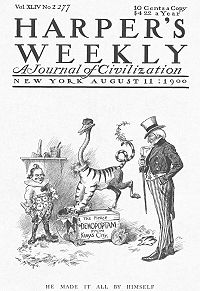

| − | * [http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0811.html | + | * Political Cartoon, on 1900 presidential campaign; <ref>[Harper's Weekly "He Made It All By Himself" http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/harp/0811.html]</ref> |

* American Memory: [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/mar19.html Today in History: March 19] | * American Memory: [http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/mar19.html Today in History: March 19] | ||

*{{gutenberg author | id=William_Jennings_Bryan | name=William Jennings Bryan}} | *{{gutenberg author | id=William_Jennings_Bryan | name=William Jennings Bryan}} | ||

| − | * [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/wilson/peopleevents/p_bryan.html "William Jennings Bryan"] at ''The American Experience: Woodrow Wilson'' on [[PBS]] | + | *[http://www3.bradburyac/tenness9.html ''The Duel In the Shade'' - Darrow's examination of Bryan at the Scopes Trial] |

| − | * [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/monkeytrial/peopleevents/p_bryan.html "William Jennings Bryan"] at ''The American Experience: The Monkey Trial'' on [[PBS]] | + | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/wilson/peopleevents/p_bryan.html "William Jennings Bryan"] at ''The American Experience: Woodrow Wilson'' on [[PBS]] |

| − | * [http://www.geocities.com/vachellindsaybryan Text of Vachel Lindsay's famous poem honoring Bryan.] | + | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/monkeytrial/peopleevents/p_bryan.html "William Jennings Bryan"] at ''The American Experience: The Monkey Trial'' on [[PBS]] |

| − | * [http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?query=william+jennings+bryan&queryType=%40attr+1%3D1 William Jennings Bryan cylinder recordings], from the [[Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project]] at the [[University of California, Santa Barbara]] Library. | + | *[http://www.mockconforum.com/blog Washington & Lee Mock Convention] |

| − | * [http://www.wamu.org/programs/dr/06/02/15.php Michael Kazin: "A Godly Hero" interview about Jennings on The Diane Rehm Show] | + | *[http://www.geocities.com/vachellindsaybryan Text of Vachel Lindsay's famous poem honoring Bryan.] |

| − | * [http://www.gotothebible.com/HTML/Sermons/deity.html "The Deity of Christ" - paper by Bryan on the subject] | + | *[http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/search.php?query=william+jennings+bryan&queryType=%40attr+1%3D1 William Jennings Bryan cylinder recordings], from the [[Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project]] at the [[University of California, Santa Barbara]] Library. |

| − | * [http://www.popcorn78.blogspot.com/2006/05/deleted-scenes.html Information on Bryan's thought and influence, including quotations from his speeches and writings.] | + | *[http://www.wamu.org/programs/dr/06/02/15.php Michael Kazin: "A Godly Hero" interview about Jennings on The Diane Rehm Show] |

| − | * [http://www.wsws.org/articles/2006/aug2006/brya-a11.shtml Author Shannon Brown examines Bryan's position on racism.] | + | *[http://www.gotothebible.com/HTML/Sermons/deity.html "The Deity of Christ" - paper by Bryan on the subject] |

| − | * {{imdb name|id=0117021|name=William Jennings Bryan}} | + | *[http://www.popcorn78.blogspot.com/2006/05/deleted-scenes.html Information on Bryan's thought and influence, including quotations from his speeches and writings.] |

| − | * [http://boomp3.com/m/7acabc5ec205 William Jennings Bryan: The Ideal Republic] (listen online) | + | *[http://www.wsws.org/articles/2006/aug2006/brya-a11.shtml Author Shannon Brown examines Bryan's position on racism.] |

| − | * [http://www.themonkeytrial.com Side-by-side comparison of the Scopes trial with the film version of Inherit the Wind] | + | *{{imdb name|id=0117021|name=William Jennings Bryan}} |

| − | * [http://www.nebraskahistory.org/lib-arch/research/manuscripts/politics/bryanwj.htm William Jennings Bryan papers] at [[Nebraska State Historical Society]] | + | *[http://boomp3.com/m/7acabc5ec205 William Jennings Bryan: The Ideal Republic] (listen online) |

| − | * | + | *[http://www.themonkeytrial.com Side-by-side comparison of the Scopes trial with the film version of Inherit the Wind] |

| + | *[http://www.nebraskahistory.org/lib-arch/research/manuscripts/politics/bryanwj.htm William Jennings Bryan papers] at [[Nebraska State Historical Society]] | ||

| + | *{{findagrave|141}} Retrieved on [[2008-02-11]] | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| Line 236: | Line 310: | ||

|ALTERNATIVE NAMES= | |ALTERNATIVE NAMES= | ||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION=[[United States Secretary of State]] | |SHORT DESCRIPTION=[[United States Secretary of State]] | ||

| − | |DATE OF BIRTH=March 19, 1860 | + | |DATE OF BIRTH=[[March 19]], [[1860]] |

|PLACE OF BIRTH=[[Salem, Illinois]], [[United States|U.S.]] | |PLACE OF BIRTH=[[Salem, Illinois]], [[United States|U.S.]] | ||

| − | |DATE OF DEATH=July 26, 1925 | + | |DATE OF DEATH=[[July 26]], [[1925]] |

|PLACE OF DEATH=[[Dayton, Tennessee]], [[United States|U.S.]] | |PLACE OF DEATH=[[Dayton, Tennessee]], [[United States|U.S.]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| Line 248: | Line 321: | ||

[[Category:Politics_and_social_sciences]] | [[Category:Politics_and_social_sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Politics]] | [[Category:Politics]] | ||

| − | {{credits| | + | {{credits|227640496}} |

Revision as of 05:23, 27 July 2008

| William Jennings Bryan | |

| Incumbent | |

| In office since November 3, 1896 | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office March 5, 1913 | |

| Born | |

|---|---|

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Mary Baird Bryan |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was the Democratic Party nominee for President of the United States in 1896, 1900 and 1908, a lawyer, and the 41st United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson. One of the most popular speakers in American history, he was noted for a deep, commanding voice. Bryan was a devout Presbyterian, a supporter of popular democracy, a critic of banks and railroads, a leader of the silverite movement in the 1890s, a leading figure in the Democratic Party, a peace advocate, a prohibitionist, an opponent of Social Darwinism, and one of the most prominent leaders of Populism in late 19th- and early 20th century. Because of his faith in the goodness and rightness of the common people, he was called "The Great Commoner." In the intensely fought 1896 election and 1900 election, he was defeated by William McKinley but retained control of the Democratic Party. For presidential candidates, Bryan invented the national stumping tour. In his three presidential bids, he promoted Free Silver in 1896, anti-imperialism in 1900, and trust-busting in 1908, calling on Democrats, in cases where corporations are protected, to renounce states rights to fight the trusts and big banks, and embrace populist ideas. President Woodrow Wilson appointed him Secretary of State in 1913, but Wilson's handling of the Lusitania crisis in 1915 caused Bryan to resign in protest. He was a strong supporter of Prohibition in the 1920s, but is probably best known for his crusade against Darwinism, which culminated in the Scopes Trial in 1925. Five days after the case was decided, he died in his sleep. [1]

Background and early career: 1860–1896

The son of Silas and Mary Ann Bryan, Bryan was born in the Little Egypt region of southern Illinois on March 19, 1860,

Bryan's mother was a Methodist born of English heritage [2]. Mary Bryan joined the Salem Baptists in 1872, so Bryan attended Methodist services on Sunday morning, and in the afternoon, Baptist services. At this point, William began spending his Sunday afternoons at the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. At age fourteen in 1874, Bryan attended a revival, was baptized, and joined the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In later life, Bryan said the day of his baptism was the most important day in his life, but, at the time it caused little change in his daily routine. In favor of the larger Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, Bryan left the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.

His father Silas Bryan, was born of Protestant-Irish and English stock in Virginia. (Asked when his family "dropped the the 'O'" from his surname he responded there never had been an "O".) [3] As a Jacksonian Democrat, Silas won election to the Illinois State Senate, where he worked among Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. The year of William Jennings Bryan's birth, Silas lost his seat but shortly won election to be a state circuit judge.

The family moved to a 520-acre (2.1 km²) farm north of Salem in 1866, living in a ten-room house that was the envy of Marion County.

Until age ten, Bryan was home schooled, finding in the Bible and McGuffey Readers the views gambling and liquor are evil and sinful. To attend Whipple Academy, the academy attached to Illinois College, 14-year-old Bryan was sent to Jacksonville in 1874.

Following high school, he entered Illinois College and studied classics, graduating as valedictorian in 1881. During his time at Illinois College, Bryan was a member of the Sigma Pi literary society. To study law at Union Law College, he moved to Chicago. While preparing for the bar exam, he taught high school. While teaching, he eventually married pupil Mary Elizabeth Baird in 1884. They settled in Salem, Illinois, a young town with a population of two thousand.

Mary became a lawyer and collaborated with him on all his speeches and writings. He practiced law in Jacksonville (1883–87), then moved to the boom city of Lincoln, Nebraska.

In the Democratic landslide of 1890, Bryan was elected to Congress and reelected by 140 votes in 1892. He ran for the Senate in 1894, but was overwhelmed in the Republican landslide.

In Bryan's first years in Lincoln, he traveled to Valentine, Nebraska on business where he met an aspiring young cattleman named James Dahlman. Over the next forty years they remained friends, with Dahlman carrying Nebraska for Bryan twice while he was state Democratic Party chairman. Even when Dahlman became closely associated with Omaha's vice elements, including the breweries, as the city's eight-term mayor, he and Bryan maintained a collegial relationship.[4]

First campaign for the White House: 1896

At the 1896 Democratic National Convention, Bryan delivered a famous speech lambasting Eastern monied classes for supporting the gold standard at the expense of the average worker. The speech is known as the "Cross of Gold" speech.

Over the Bourbon Democrats who long controlled the party and supported incumbent conservative President Grover Cleveland, the party's agrarian and silver factions voted for Bryan, giving him the nomination of the Democratic Party. At thirty six, Bryan was the youngest presidential nominee ever.

In addition, Bryan formally received the nominations of the Populist Party and the Silver Republican Party. Without crossing party lines, voters from any party could vote for him. The Populists nominated him only once (in 1896); they refused to do so in previous and later elections mostly due to an incident that occurred during the 1896 election.

Along with nominating Bryan for president, for the vice presidency, the Populists nominated Georgia Representative Thomas E. Watson in hope Bryan would choose Watson to be his Democratic running mate. However, Bryan chose Maine industrialist and politician Arthur Sewall. The Populist Party was greatly disappointed and thereafter paid little attention to him.[citation needed]

General Election

On a program of prosperity through industrial growth, high tariffs and sound money (that is, gold.), the Republicans nominated William McKinley. Republicans ridiculed Bryan as a Populist. However, "Bryan's reform program was so similar to that of the Populists that he has often been mistaken for a Populist, but he remained a staunch Democrat throughout the Populist period."[5]

Bryan demanded Bimetallism and "Free Silver" at a ratio of 16:1. Most leading Democratic newspapers rejected his candidacy.

Republicans discovered, by August, Bryan was solidly ahead in the South and West, but far behind in the Northeast. He appeared to be ahead in the Midwest, so the Republicans concentrated their efforts there. They said Bryan was a madman—a religious fanatic surrounded by anarchists—who would wreck the economy. [citation needed] By late September, the Republicans felt they were ahead in the decisive Midwest and began emphasizing that McKinley would bring prosperity to all Americans. McKinley scored solid gains among the middle classes, factory and railroad workers, prosperous farmers and among the German Americans who rejected free silver. Bryan gave five hundred speeches in twenty seven states. William McKinley won by a margin of 271 to 176 in the electoral college.

War and peace: 1898–1900

Bryan volunteered for combat in the Spanish-American War in 1898, arguing, "Universal peace cannot come until justice is enthroned throughout the world. Until the right has triumphed in every land and love reigns in every heart, government must, as a last resort, appeal to force." Bryan became colonel of a Nebraska militia regiment; he spent the war in Florida and never saw combat. After the war, Bryan opposed the annexation of the Philippines (though he did support the Treaty of Paris that ended the war).

Presidential Election of 1900

He ran as an anti-imperialist, finding himself in alliance with Andrew Carnegie and other millionaires. Republicans mocked Bryan as indecisive, or a coward; Henry Littlefield argued the portrayal of the Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published that year, reflected this.

Bryan combined anti-imperialism with free silver, saying:

The nation is of age and it can do what it pleases; it can spurn the traditions of the past; it can repudiate the principles upon which the nation rests; it can employ force instead of reason; it can substitute might for right; it can conquer weaker people; it can exploit their lands, appropriate their property and kill their people; but it cannot repeal the moral law or escape the punishment decreed for the violation of human rights.[6]

In a typical day he gave four hour-long speeches and shorter talks that added up to six hours of speaking. At an average rate of 175 words a minute, he turned out 63,000 words, enough to fill 52 columns of a newspaper. (No paper printed more than a column or two.) In Wisconsin, he once made 12 speeches in 15 hours.[7]. He held his base in the South, but lost part of the West as McKinley retained the Northeast and Midwest and rolled up a landslide.

On the Chautauqua circuit: 1900–1912

Following his presidential bid, the forty year-old Bryan said he was letting politics obscure his calling as a Christian.[citation needed]

For the next twenty five years, Bryan was the most popular Chautauqua speaker,[citation needed] delivering thousands of speeches, even while serving as secretary of state. He mostly spoke about religion but covered a wide variety of topics.[citation needed] His most popular lecture (and his personal favorite) was a lecture entitled "The Prince of Peace": in it, Bryan stressed religion was the solid foundation of morality, and individual and group morality was the foundation for peace and equality. Another famous lecture from this period, "The Value of an Ideal", was a stirring call to public service.

In 1905 speech, Bryan warned: "The Darwinian theory represents man reaching his present perfection by the operation of the law of hate - the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak. If this is the law of our development then, if there is any logic that can bind the human mind, we shall turn backward to the beast in proportion as we substitute the law of love. I choose to believe that love rather than hatred is the law of development."

Bryan threw himself into the work of the Social Gospel. Bryan served on organizations containing a large number of theological liberals: he sat on the temperance committee of the Federal Council of Churches and on the general committee of the short-lived Interchurch World Movement.

Bryan founded a weekly magazine, The Commoner, calling on Democrats to dissolve the trusts, regulate the railroads more tightly and support the Progressive Movement. He regarded prohibition as a "local" issue and did not endorse it until 1910. In London in 1906, he presented a plan to the Inter-Parliamentary Peace Conference for arbitration of disputes that he hoped would avert warfare. He tentatively called for nationalization of the railroads, then backtracked and called only for more regulation. His party nominated gold bug Alton B. Parker in 1904, but Bryan was back in 1908, losing this time to William Howard Taft.

Bryan's speech to the students of Washington and Lee University began the Washington & Lee Mock Convention.

Secretary of State: 1913–1915

For supporting Woodrow Wilson for the presidency in 1912, he was appointed as Secretary of State.[citation needed] However, Wilson only nominally consulted Bryan and made all the major foreign policy decisions. Bryan negotiated twenty eight treaties that promised arbitration of disputes before war broke out between countries and the United States; onto which Germany never signed. In the civil war in Mexico in 1914, he supported American military intervention.

Bryan resigned in June 1915 over Wilson's strong notes demanding "strict accountability for any infringement of [American] rights, intentional or incidental." He campaigned for Wilson's reelection in 1916. When war was declared in April 1917, Bryan wrote Wilson, "Believing it to be the duty of the citizen to bear his part of the burden of war and his share of the peril, I hereby tender my services to the Government. Please enroll me as a private whenever I am needed and assign me to any work that I can do."[8] Wilson, however, did not allow Bryan to rejoin the military and did not offer him any wartime role, so Bryan campaigned for the later adopted Constitutional amendments on prohibition and women's suffrage.

Prohibition battles: 1916–1925

Partly to avoid Nebraska ethnics such as the German Americans who were "wet" and opposed to prohibition, [9] Bryan moved to Miami, Florida. Bryan filled lucrative speaking engagements and was extremely active in Christian organizations. Deeming him not dry enough, he refused to support the party's presidential nominee James M. Cox in 1920. As one biographer explains,

| “ | Bryan epitomized the prohibitionist viewpoint: Protestant and nativist, hostile to the corporation and the evils of urban civilization, devoted to personal regeneration and the social gospel, he sincerely believed that prohibition would contribute to the physical health and moral improvement of the individual, stimulate civic progress, and end the notorious abuses connected with the liquor traffic. Hence he became interested when its devotees in Nebraska viewed direct legislation as a means of obtaining antisaloon laws.[10] | ” |

Bryans' national campaigning helped Congress pass the 18th Amendment in 1918, which shut down all saloons as of 1920. While prohibition was in effect, however, Bryan did not work to secure better enforcement. He ignored[citation needed] the Ku Klux Klan, expecting it would soon fold. For the nomination in 1924, he opposed the wet Al Smith and his brother, Nebraska Governor Charles W. Bryan, was put on the ticket with John W. Davis as candidate for vice president to keep the Bryanites in line. Bryan was very close to his younger brother Charles and endorsed him for the vice presidency.

Bryan was the chief proponent of the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, the precursor to our modern War on Drugs. However, he argued for the act's passage more as an international obligation than on moral grounds.[11]

Fighting Darwinism: 1918–1925

Before World War I, Bryan believed moral progress could achieve equality at home and, in the international field, peace between all the world's nations.

In his famous Chautauqua lecture, "The Prince of Peace," Bryan warned the theory of evolution could undermine the foundations of morality. However, he concluded, "While I do not accept the Darwinian theory I shall not quarrel with you about it."

However, the First World War convinced Bryan that Darwinism undermined morality[citation needed] and moral progress had ground to a complete halt.

Bryan was heavily influenced by Vernon Kellogg's 1917 book, Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in Belgium and France,[citation needed] which forwarded that most German military leaders were committed Darwinists skeptical of Christianity, and The Science of Power by Benjamin Kidd (1918),[citation needed] which attributed the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche to German nationalism, materialism, and militarism which in turn was the outworking of the Darwinian hypothesis.

In 1920, Bryan told the World Brotherhood Congress Darwinism was "the most paralyzing influence with which civilization has had to deal in the last century" and that Nietzsche, in carrying Darwinism to its logical conclusion, "promulgated a philosophy that condemned democracy... denounced Christianity... denied the existence of God, overturned all concepts of morality... and endeavored to substitute the worship of the superhuman for the worship of Jehovah."[citation needed]

However, it was not until 1921 that Bryan saw Darwinism as a major internal threat to the US. The major study which seemed to convince Bryan of this was James H. Leuba's The Belief in God and Immortality, a Psychological, Anthropological and Statistical Study (1916). In this study, Leuba shows during four years of college a considerable number of college students lost their faith. Bryan was horrified that the next generation of American leaders might have the degraded sense of morality which he believed had prevailed in Germany and caused the Great War. Bryan then launched an anti-evolution campaign.

A November 1924 cartoon depicts Bryan with his brother, Charles, sitting on a log marked "Almost the Solid South" looking at the sun marked "1928" where more hope might come for them. Charles unsuccessfully ran for the vice presidency in the 1924 election having lost a number of southern states.

When Union Theological Seminary in Virginia invited Bryan to deliver the James Sprunt Lectures, the campaign kicked off in October 1921. The heart of the lectures was a lecture entitled "The Origin of Man", in which Bryan asked, "what is the role of man in the universe and what is the purpose of man?" For Bryan, the Bible was absolutely central to answering this question, and moral responsibility and the spirit of brotherhood could only rest on belief in God.

The Sprunt lectures were published as In His Image, and sold over 100,000 copies, while "The Origin of Man" was published separately as The Menace of Darwinism and also sold very well.

Bryan was worried that Darwinism was making grounds not only in the universities, but also within the church itself. Many colleges were still church-affiliated at this point. The developments of 19th century liberal theology, and higher criticism in particular, had left the door open to the point where many clergymen were willing to embrace Darwinism and claimed that it was not contradictory with their being Christians. Determined to put an end to this, Bryan, who had long served as a Presbyterian elder, decided to run for the position of Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, which was at the time embroiled in the Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy. (Under presbyterian church governance, clergy and laymen are equally represented in the General Assembly, and the post of Moderator is open to any member of General Assembly.) Bryan's main competition in the race was the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the College of Wooster, who had loudly endorsed the teaching of Darwinism in the college. Bryan lost to Wishart by a vote of 451-427. Bryan then failed in a proposal to cut off funds to schools where Darwinism was taught. Instead the General Assembly announced disapproval of materialistic (as opposed to theistic) evolution.

According to author Ronald L. Numbers, Bryan was not nearly as much of a fundamentalist as many modern day creationists and is more accurately described as a "day-age creationist.":

- William Jennings Bryan, the much misunderstood leader of the post–World War I antievolution crusade, not only read the Mosaic “days” as geological “ages” but allowed for the possibility of organic evolution— so long as it did not impinge on the supernatural origin of Adam and Eve.[12]

Scopes Trial: 1925

In addition to his unsuccessful advocacy of banning the teaching of evolution in church-run universities, Bryan also actively lobbied in favor of state laws banning public schools from teaching evolution. The legislatures of several southern states proved more receptive to his anti-evolution message than the Presbyterian Church had, and consequently passed laws banning the teaching of evolution in public schools after Bryan addressed them. A prominent example was the Butler Act of 1925, making it unlawful in Tennessee to teach that mankind evolved from lower life forms.[13]

Bryan's participation in the highly publicized 1925 Scopes Trial served as a capstone to his career. He was asked by William Bell Riley to represent the World Christian Fundamentals Association as counsel at the trial. During the trial Bryan took the stand and was questioned by defense lawyer Clarence Darrow about his views on the Bible. Biologist Stephen Jay Gould has speculated that Bryan's antievolution views were a result of his Populist idealism and suggests that Bryan's fight was really against Social Darwinism. Others, such as biographer Michael Kazin, reject that conclusion based on Bryan's failure during the trial to attack the eugenics in the textbook, Civic Biology.[14] The national media reported the trial in great detail, with H. L. Mencken using Bryan as a symbol of Southern ignorance and anti-intellectualism. In a more humorous vein, satirist Richard Armour stated in It All Started With Columbus that Darrow had "made a monkey out of" Bryan.

The trial concluded with a directed verdict of guilty, which the defense encouraged, as their aim was to take the law itself to a higher court in order to challenge its constitutionality.

Immediately after the trial, he continued to edit and deliver speeches, traveling hundreds of miles that week. On Sunday, July 26 1925, he drove from Chattanooga to Dayton to attend a church service, ate a meal and died in his sleep that afternoon—five days after the trial ended. School Superintendent Walter White proposed that Dayton should create a Christian college as a lasting memorial to Bryan; fund raising was successful and Bryan College opened in 1930. Bryan is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His tombstone reads "He kept the Faith." He was survived by among others, a daughter, Congresswoman Ruth Bryan Owen.

Popular image

The 1950s play by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, Inherit the Wind, is a fictionalized account of the Scopes Trial written in response to McCarthyism. A populist thrice-defeated Presidential candidate from Nebraska named Matthew Harrison Brady comes to a small town named Hillsboro in the deep south to help prosecute a young teacher for teaching Darwin to his schoolchildren. He is opposed by a famous liberal lawyer, Henry Drummond, and chastised by a cynical newspaperman as the trial assumes a national profile. Critics of the play charge that it mischaracterizes Bryan and the trial.

Bryan also appears as a character in Douglas Moore's 1956 opera, The Ballad of Baby Doe and is briefly mentioned in John Steinbeck's East of Eden. His death is referred to in Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises. Bryan was also mentioned on the May 23, 2007 episode of The Daily Show when fictional comedian Geoffrey Foxworthington (an early 20th century parody of Jeff Foxworthy) quotes, "If your dream Vice President is William Jennings Bryan, you might be a puzzlewit." In Robert A. Heinlein's Job: A Comedy of Justice, Bryan's unsuccessful or successful runs for the presidency are seen as the 'splitting off' events of the alternate histories through which the protagonists travel.

Legacy

Kazin (2006) considers him the first of the 20th century "celebrity politicians" better known for their personalities and communications skills than their political views. Shannon Jones (2006) writes that one of the few topics touched on by historians is Bryan's apparent support of American racism, pointing that Bryan never took a principled stand against white supremacy in the Southern United States. Jones explains that "the ruling elite in the South, the remnants of the old southern slaveholding oligarchy, formed a critical base of the Democratic Party. This Party had defended slavery and secession and had led the struggle against post-Civil War Reconstruction. It had opposed granting suffrage to freed slaves and generally opposed all progressive reforms aimed at alleviating the oppression of blacks and poor whites. No politician could hope for national leadership in the Democratic Party, let alone expect to win the presidency, by attacking the system of racial oppression in the South."

Alan Wolfe has concluded that Bryan's "legacy remains complicated." Form and content mix uneasily in Bryan's politics. The content of his speeches leads in a direct line to the progressive reforms adopted by 20th century Democrats. But the form his actions took—-a romantic invocation of the American past, a populist insistence on the wisdom of ordinary folk, a faith-based insistence on sincerity and character.

In "They Also Ran", Irving Stone criticized Bryan as a person who was egocentric and never admitted wrong. Stone mentioned how Bryan lived a sheltered life and therefore could not feel the suffering of the common man. He speculated that Bryan merely acted as a champion of the common man in order to get their votes. Irving Stone mentioned that none of his ideas were original and that he did not have the brains to be an effective president. Stone personally believed Bryan to be one of the nation's worst Secretaries of State. He also feared that Bryan would have supported many radical religious blue laws. Stone felt that Bryan had one of the most undisciplined minds of the 19th century and that McKinley, Roosevelt, and Taft all made better presidents.

Bryan County, Oklahoma was named after him.[15] Bryan Memorial Hospital (now BryanLGH Medical Center) of Lincoln, Nebraska, and Bryan College located in Dayton, Tennessee, are also named for William Jennings Bryan. The William Jennings Bryan House in Nebraska was named a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1963.