United States Electoral College

The United States Electoral College is a term used to describe the 538 [1] Presidential electors who meet every four years to cast the official votes for President and Vice President of the United States. The Constitution gives each state legislature the plenary power to choose the electors who shall represent its state in the Electoral College. Through this constitutional authority, each state legislature also has the power to determine how exactly the electors are to be chosen (including the legislature choosing the electors).

The original mechanics of presidential elections were established by Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution. Originally, each elector had two votes for President, with the winner becoming President and the runner-up becoming Vice President. The Twelfth Amendment revised those mechanics, requiring that each elector vote separately for President and Vice President. Today, the mechanics of the Presidential election are administered by the National Archives and Records Administration via its Office of the Federal Register.

Background

At the Constitutional Convention, the Virginia Plan used as the basis for discussions called for the Executive to be elected by the Legislature.[2] Delegates from a majority of states agreed to this mode of election.[3] However, a committee formed to work out various details, including the mode of election of the President, recommended instead that the election be by a group of people apportioned among the states in the same numbers as their representatives in Congress (the formula for which had been resolved in lengthy debates resulting in the Connecticut Compromise and Three-fifths compromise), but chosen by each state "in such manner as its Legislature may direct." Committee member Gouverneur Morris explained the reasons for the change; among others, there were fears of "intrigue" if the President was chosen by a small group of men who met together regularly, as well as concerns for the independence of the Office of the President.[4] Though some delegates preferred popular election, the committee's proposal was approved, with minor modifications, on September 6.[5]

In the Federalist Papers No. 39, James Madison argued that the Constitution was designed to be a mixture of federal (state-based) and national (population-based) government. The Congress would have two houses, one federal and the other national in character, while the President would be elected by a mixture of the two modes, giving some electoral power to the states and some to the people in general. Both the Congress and the President would be elected by mixed federal and national means.[6]

Origin of name

The name Electoral College is not given in the United States Constitution, and it was not until the early 1800s that it came into general usage as the designation for the group of citizens selected to cast votes for President and Vice President. It was first written into Federal law in 1845, and today the term appears in , in the section heading and in the text as "college of electors."[7]

Original plan

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution states:

| â | Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector. | â |

It then goes on to describe how the electors vote for President.

Article II, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution states:

| â | The Congress may determine the Time of choosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States. | â |

Article II, Section 1, Clause 3 of the Constitution provided for the original fashion by which the President and Vice President were to be chosen by the electors. The primary difference was that each elector voted for two Persons for President, rather than one vote for President and one vote for Vice President. After the choosing of the President, whoever had the most electoral votes, among the remaining candidates, would become the Vice President.

The emergence of political parties complicated matters in the elections of 1796 and 1800. In 1796, the winner of the election was John Adams, a member of the Federalist Party, and the runner up (and therefore the new Vice President) was Thomas Jefferson, a member of the opposition Democratic-Republican Party.

In 1800, the candidates of the Democratic-Republican Party (Jefferson for President and Aaron Burr for Vice President) each tied for first place. However, since all electoral votes were for President, Burr's votes were technically for President even though he was his party's second choice. Jefferson was so hated by Federalists that the party members sitting in Congress tried to elect Burr. The Congress deadlocked for 35 ballots as neither candidate received the necessary vote of a majority (nine) of the state delegations in the House. Only after Federalist Party leader Alexander Hamiltonâwho disliked Burrâmade known his preference for Jefferson was the issue resolved on the 36th ballot.

In response to those elections, the Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendmentâallowing electors to cast one vote for President and one vote for Vice Presidentâreplacing the system outlined in Article II, Section 1, Clause 3. The Twelfth Amendment was proposed in 1803 and adopted in 1804.

Electoral College mechanics

The election of both the President and Vice President of the United States is indirect. The constitutional theory is that, while the Congress is popularly elected by the people,[8] the President and Vice President are elected to be executives of a federation of independent states.

Presidential Electors are selected on a state-by-state basis, as determined by the laws of each state. Each state uses the popular vote on Election Day to appoint electors (this was not the case for all states in the 18th and 19th century). Although ballots list the names of the presidential candidates, voters within the 50 states and Washington, D.C. actually choose electors for their state when they vote for President and Vice President. These Presidential Electors in turn cast electoral votes for those two offices. Even though the aggregate national popular vote is calculated by state officials and media organizations, the national popular vote is not the basis for electing the President or Vice President.

A candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270) to win the Presidency. If no candidate receives a majority in the election for President, or Vice President, that election is determined via a contingency procedure in the Twelfth Amendment, explained in detail below.

Apportionment of electors

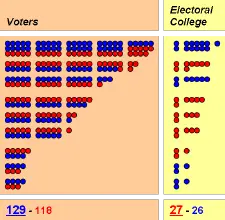

The size of the Electoral College is equal to the total membership of both Houses of Congress (435 Representatives and 100 Senators) plus the three electors allocated to the District of Columbia (Washington, D.C.), totaling 538 electors.

Each state is allocated as many electors as it has Representatives and Senators in the United States Congress.[9] Since the most populous states have the most seats in the House of Representatives, they also have the most electors. The six states with the most electors are California (55), Texas (34), New York (31), Florida (27), Pennsylvania (21) and Illinois (21). The seven smallest states by populationâAlaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyomingâeach have three electors. The number of representatives for each state is determined decennially by the United States Census, thus determining the number of electoral votes for each state until the next census reallocation.

Under the Twenty-third Amendment, Washington, D.C. is allocated as many electors as it would have if it were a state, except that it cannot have more electors than the least populous state. The least populous state (currently Wyoming) has three electors; thus, D.C. cannot have more than three electors itself. Even if the District of Columbia were a state, its current population would entitle it to three electors; based on its population per electoral vote, Washington, D.C. has the second highest per-capita electoral college representation, after Wyoming.

Choosing of electors

Nomination of electors

Potential elector candidates are nominated by their state political parties in the months prior to Election Day. The U.S. Constitution delegates to each state the authority for nominating and choosing its electors. In some states, the electors are nominated in primaries, the same way that other candidates are nominated. Other states, such as Oklahoma, Virginia and North Carolina, nominate electors in party conventions. In Pennsylvania, the campaign committees of each candidate name their candidates for Presidential Elector (an attempt to discourage faithless electors).) All states require the names of all electors to be filed with the state's Secretary of State (or equivalent) at least a month prior to Election Day.

Election of electors

U.S. law sets Election Day for federal offices on the first Tuesday following the first Monday in November. The electors pledged to a particular candidate are formally chosen in the popular election held on that day.

All statesâexcept twoâemploy the winner-takes-all method, awarding their Presidential Electors as an indivisible bloc. The exceptions, Maine and Nebraska, select one elector within each congressional district by popular vote, and additionally select the remaining two electors by the aggregate, statewide popular vote. This method has been used in Maine since 1972, and in Nebraska since 1992, though neither has ever split its electoral votes in any elections since implementing this method.

Disqualification of electors

Under Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution, no person holding a federal office, either elected or appointed, may become an elector.[10] Under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, any person who has sworn an oath to support the United States Constitution in order to hold either a state or federal office, and has then later rebelled against the United States, is barred from serving in the Electoral College. However, the Congress may remove this disability by a two-thirds vote in both Houses.

Meetings of electors

Electors meet in their respective state capitals (or in the case of Washington, D.C., within the District) on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December, at which time they cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for President and Vice President.

The Electoral College never meets as one body. Although procedures in each state vary slightly, the electors generally follow a similar series of steps, and the Congress has constitutional authority to regulate the procedures the states follow. The meeting is opened by the election certification officialâoften each state's Secretary of State (or equivalent)âwho reads the Certificate of Ascertainment. This document sets forth who was chosen to cast the electoral votes. Those present answer to their name, and they then fill any vacancies in their number. The next step is the selection of a president or chairman of the meeting, sometimes also with a vice chairman. The electors sometimes choose a secretary, oftentimes not himself an elector, to take the minutes of the meeting. In many states, political officials give short speeches at this point in the proceedings.

When the time for balloting arrives, the electors choose one or two people to act as tellers. Some states provide for the placing in nomination of a candidate to receive the electoral votes (the candidate for President of the political party of the Electors). Each elector submits a written ballot with the name of a candidate for President. In New Jersey, the electors cast ballots by checking the name of the candidate on a pre-printed card; in North Carolina, the electors write the name of the candidate on a blank card. The tellers count the ballots and announce the result. The next step is the casting of the vote for Vice President, which follows a similar pattern.

After the voting is complete, the electors complete the Certificate of Vote. This document states the number of electoral votes cast for President and Vice President, and who received those votes. The state election official usually has pre-printed forms ready, and the tellers usually only write down the number of votes cast for appropriate candidates. Five copies of the Certificate of Vote are completed and signed by each Elector. Multiple copies of the Certificate of Vote are signed, in order to provide multiple originals in case one is lost. One copy is sent to President of the U.S. Senate (the sitting Vice President of the United States) by certified mail.

A staff member of the Office of the Vice President (with the Vice President acting in his capacity as President of the Senate) collects the Certificates of Vote as they arrive and prepares them for the joint session of Congress. The Certificates are arrangedâunopenedâin alphabetical order and placed in two special mahogany boxes. The states Alabama through Missouri (including the District of Columbia) are placed in one box, and the states Montana through Wyoming are placed in the second box.

Faithless electors

A faithless elector is one who casts an electoral vote for someone other than whom they have pledged to elect, or who refuses to vote for any candidate. In 158 instances, electors have not cast their votes for the Presidential or Vice Presidential candidate to whom they were pledged. Of those, 71 votes were changed because the original candidate died before the elector was able to cast a vote. Two votes were not cast at all when electors chose to abstain from casting their electoral vote for any candidate. The remaining 85 were changed by the elector's personal interest, or perhaps by accident. Usually, the faithless electors act alone. An exception was in 1836, when 23 Virginia electors changed their votes together. In that year, Martin Van Buren's Vice Presidential running mate, Richard Johnson, did not receive an absolute majority of electoral votes for Vice President, but ultimately won the office on the first ballot by the United States Senate in 1837.

There are laws to punish faithless electors in 24 states. In 1952, the constitutionality of state pledge laws was brought before the Supreme Court in Ray v. Blair.[11] The Court ruled in favor of state laws requiring electors to pledge to vote for the winning candidate, as well as remove electors who refuse to pledge. As stated in the ruling, electors are acting as a functionary of the state, not the federal government. Therefore, states have the right to govern electors. The constitutionality of state laws punishing electors for actually casting a faithless vote, rather than refusing to pledge, has never been decided by the Supreme Court. While many states may only punish a faithless elector after-the-fact, some such as Michigan have the power to cancel his or her vote.[12]

As electoral slates are typically chosen by the political party or the party's presidential nominee, electors usually have high loyalty to the party and its candidate.

While not a "faithless elector" as such, there have been two instances in which a candidate died between the selection of the electors in November and the Electoral College vote in December. In the election of 1872, Democratic candidate Horace Greeley passed away before the meeting of the Electoral College; the electors who were to have voted for Greeley, finding themselves in a state of disarray, split their votes across several candidates, including three votes cast for the deceased Greeley. However, President Ulysses S. Grant, the Republican incumbent, had already won an absolute majority of electors. Because it was the death of a losing candidate, there was no pressure to agree on a replacement candidate. Similarly, in the election of 1912, after the Republicans had nominated incumbent President William Howard Taft and Vice President James S. Sherman, Sherman died shortly before the election, too late to change the names on the ballot, thus causing Sherman to be listed posthumously. That ticket finished third behind the Democrats (Woodrow Wilson) and the Progressives (Theodore Roosevelt), and the eight electoral votes that Sherman would have received were cast instead for Nicholas M. Butler. Electors pledged to a dead candidate are free to vote for whomever they wish just as are electors pledged to a live candidate.

Faithless electors have not changed the outcome of a presidential election in any election to date.

Joint Session of Congress and the Contingent Election

The Twelfth Amendment mandates that the Congress assemble in joint session.[13] Additionally, federal law mandates that such joint session to count the electoral votes and declare the winners of the election take place on the sixth day of January in the calendar year immediately following the meetings of the Presidential Electors.[14] The meeting is held at 1:00 p.m. in the Chamber of the U.S. House of Representatives. The sitting Vice President is expected to preside, but in several cases the President pro tempore of the Senate has chaired the proceedings instead. The Vice President and the Speaker of the House sit at the podium, with the Vice President in the seat of the Speaker of the House. Senate pages bring in the two mahogany boxes containing each state's certified vote and place them on tables in front of the Senators and Representatives. Each house appoints two tellers to count the vote. Relevant portions of the Certificate of Vote are read for each state, in alphabetical order. If there are no objections, the presiding officer declares the result of the vote and, if applicable, states who is elected President and Vice President. The Senators then depart from the House Chamber.

Contingent Presidential election by House

Pursuant to the Twelfth Amendment, the House of Representatives is required to go into session "immediately" to vote for President if no candidate for President receives a majority (270 votes) of the 538 possible electoral votes.

In this event, the House of Representatives is limited to choosing from among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each state delegation has a single vote, decided by majority decision (an evenly divided delegation is considered to abstain from voting). Additionally, delegations from at least two-thirds of all the states must be present for voting to take place. To be elected, a candidate must receive the absolute majority of state votes (currently 26); that candidate is then declared the President-elect. If no candidate receives a majority, the House proceeds to a second ballot and continues balloting until a candidate receives an absolute majority of the state votes. This situation would most likely occur only when more than two candidates receive electoral votes, but could happen in an election in which two candidates receive 269 electoral votes.

To date, the House of Representatives has chosen the President on only two occasions: in 1801 and in 1825.

Contingent Vice Presidential election by Senate

If no candidate for Vice President receives an absolute majority of electoral votes, then the Senate must go into session to elect a Vice President. The Senate is limited to choosing from only the top two candidates to have received electoral votes (one fewer than the number to which the House is limited). The Senate votes in the normal manner in this case (i.e., ballots are individually cast by each Senator, and not by State delegations). However, two-thirds of the Senators must be present for voting to take place.

Additionally, the Twelfth Amendment states that a "majority of the whole number" of Senators (currently 51 of 100) is necessary for there to be a selection of one of the two candidates. This provision essentially prohibits the sitting Vice President from casting a tie-breaking vote in the case of an evenly divided chamber.

To date, the Senate has chosen the Vice President only once, in 1837.

Deadlocked chambers

If the House of Representatives has not chosen a President-elect in time for the inauguration (noon on January 20), then Section 3 of the Twentieth Amendment specifies that the Vice President-elect becomes Acting President until the House should select a President. If the winner of the Vice Presidential election is also not known by then, then under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, the sitting Speaker of the House would become Acting President until either the House should select a President or the Senate should select a Vice President.

Alternative methods of choosing electors

The current system of choosing Presidential Electors is called the short ballot. In all states, voters choose among slates of candidates for the associated elector; only a few states list the names of the Presidential Electors on the ballot. (In some states, if a voter wishes to write in a candidate for President, the voter also is required to write in the names of candidates for elector.)

Before the advent of the short ballot in the early twentieth century, the most common means of electing the Presidential Electors was through the general ticket. The general ticket is quite similar to the current system and is often confused with it. In the general ticket, voters cast ballots for individuals running for Presidential Elector (while in the short ballot, voters cast ballots for an entire slate of electors). In the general ticket, the state canvass would report the number of votes cast for each candidate for elector, a complicated process in states like New York with multiple positions to fill. Both the general ticket and the short ballot are often considered at-large or winner-takes-all voting. The short ballot was adopted by various states at different times; it was adopted for use by North Carolina and Ohio in 1932 (possibly the first year in which it was used). Alabama was still using the general ticket as late as 1960 and was one of the last states to switch to the short ballot.

The question of the extent to which state constitutions may constrain the legislature's choice of a method of choosing electors has been touched on in two U.S. Supreme Court cases. In McPherson v. Blacker, the Court cited Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 which states that a state's electors are selected "in such manner as the legislature thereof may direct" and wrote that these words "operat[e] as a limitation upon the state in respect of any attempt to circumscribe the legislative power." In Bush v. Palm Beach County Canvassing Board, after the November 2000 presidential election, a Florida Supreme Court decision was vacated (not reversed) based on McPherson. On the other hand, three justices, dissenting in Bush v. Gore, , wrote that "nothing in Article II of the Federal Constitution frees the state legislature from the constraints in the State Constitution that created it."[15]

Arguments for and against the current system

Arguments for the current system

Maintains the federal character of the nation

The United States of America is a federal coalition; it consists of component states, each of which are joined by alliance into what was, until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment, a comparatively small, state-controlled central government. Proponents of the current system argue that the collective opinion of even a small state merits attention at the Federal level greater than that given to a small, though numerically-equivalent, portion of a very populous state.

For many years early in the nation's history, up until the Jacksonian Era, many states appointed their electors by a vote of the state legislature, and proponents argue that, in the end, the election of the President must still come down to the decisions of each state, or the federal nature of the United States will give way to a single massive, centralized government.[16]

Requires widespread popular support to win

Proponents of the Electoral College argue that organizing votes by regions forces a candidate to seek popular support over a majority of the country. Since a candidate cannot count on winning the election based solely on a heavy concentration of votes in a few areas, the Electoral College avoids much of the sectionalism that has plagued other geographically large nations.

Enhances status of minority groups

Far from decreasing the power of minority groups by depressing voter turnout, proponents argue that, by making the votes of a given state an all-or-nothing affair, minority groups can provide the critical edge that allows a candidate to win. This encourages candidates to court a wide variety of such minorities and special interests.[16] This does not apply to the states that do not employ an all-or-nothing system for selecting their electors, Maine and Nebraska; it does apply to individual electors.

Isolation of election problems

Some supporters of the Electoral College note that it isolates the impact of potential election fraud or other problems to the state where it occurs. The College prevents instances where a party dominant in one state may dishonestly inflate the votes for a candidate and thereby affect the election outcome. Recounts, for instance, occur only on a state-by-state basis, not nationwide. Similarly, the College acts to isolate less malicious election problems to the state in which they occur.[17]

Maintains separation of powers

The Constitution separated government into three branches that check each other to minimize threats to liberty and encourage deliberation of governmental acts. Under the original framework, only members of the House of Representatives were directly elected by the people, with members of the Senate chosen by state legislatures, the President by the Electoral College, and the judiciary by the President and the Senate. The President was not directly elected in part due to fears that he could assert a national popular mandate that would undermine the legitimacy of the other branches, and potentially result in tyranny.

Arguments against the current system

Unequal weight of voters

Supporters of direct election argue that it would give everyone an equally weighted vote, regardless of what state he or she lives in, and oppose giving disproportionately amplified voting power to voters in states with small populations. Under the current system, the vote of an individual living in a state with three electoral votes is proportionally more influential than the vote of an individual living in a state with a large number of electoral votes.

Essentially, the Electoral College ensures that candidates, particularly in recent elections, pay attention to key 'swing-states' (those states that are not firmly rooted in either the Republican or Democratic party). It equally assures that voters in states that are not believed to be competitive will be disregarded.

Losing the popular vote

In the elections of 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016 the candidate receiving an aggregate plurality of the popular vote did not become president.

Opponents of the Electoral College counter that it does not require candidates to cultivate greater and broader support throughout the entire nation. The electors could elect a candidate who wins by small margins in only a few of the largest states over another candidate who wins by large margins in all the rest of the states. In fact, given the 2000 allocation of electors, a candidate could have won with only the support of 11 states.

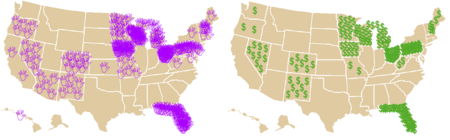

Focus on large swing states

Most states use a winner-take-all system, in which the candidate with the most votes in that state receives all of the state's electoral votes. This gives candidates an incentive to pay the most attention to states without a strong party inclination, such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Florida. For example, California, Texas, and New York, in spite of having the largest populations, have in recent elections been considered safe for a particular party (Democratic for California and New York; Republican for Texas), and therefore candidates typically devote relatively few resources, in both time and money, to such states.

It is possible to win the election by winning eleven states and disregarding the rest of the country. If one ticket were to take California (55 votes), Texas (34), New York (31), Florida (27) Illinois (21), Pennsylvania (21), Ohio (20), Michigan (17), Georgia (15), New Jersey (15), and North Carolina (15), that ticket would have 271 votes, which would be enough to win. (In fact, if a small number of voters were to vote in those eleven states, the other major ticket could have a landslide victory in the popular vote and still lose the election.) Such an extreme outcome has never occurred. In the close elections of 2000 and 2004, these eleven states gave 111 votes to Republican candidate George W. Bush and 160 votes to Democratic candidates Al Gore and John Kerry.

Proponents claim, however, that adoption of the popular vote would simply shift the disproportionate focus to large cities at the expense of rural areas.[18] Candidates might also be inclined to campaign hardest in their base areas to maximize turnout among core supporters, and ignore more closely divided parts of the country. Whether such developments would be good or bad is a matter of normative political theory and political interests of the voters in question.

Favors less populous states

As a consequence of giving more per capita voting power to the less populated states, the Electoral College gives disproportionate power to those states' interests as well. Since most states cast all of their Electoral College votes as either Republican or Democrat, Democrats often complain that the electoral college system favors the Republican party by disproportionately boosting the electoral weight of the less populous states, which have tended historically to vote Republican. Attempts have been made to show otherwise using game theory analysis, and specifically using the Banzhaf Power Index (BPI). In this model, individual voters in California (highest electoral vote count) have approximately 3.3 times the individual power to choose a president as voters of Montana (highest population with the minimum 3 electors).[19] However, Banzhaf's analysis has been critiqued as treating votes like coin-flips, and more empirically-based models of voting yield results which seem to favor larger states less.[20]

Disadvantage for third parties

In practice, the winner-take-all manner of allocating a state's electors generally decreases the importance of minor parties.[21]

Current reform proposals

For more than nineteen decades, since the 1825 congressional election of John Quincy Adams, and the epithet corrupt bargain decried by the losing Andrew Jackson, the concept of electing a president without a direct connection of the national popular vote, and the reliance upon Electoral College members who may act contrary to expressed voter preferences, has been the basis for multiple constitutional amendment proposals, books, articles and pamphlets describing the unfairness of the Electoral College process in relation to one person, one vote and other principles.[22][23]

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement among a group of U.S. states and the District of Columbia to award all their electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the overall popular vote in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The compact is designed to ensure that the candidate who receives the most votes nationwide is elected president, and it would come into effect only when it would guarantee that outcome.

The proposal centers on Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, which provides, "Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress." Many partial versions of this plan have emerged over the years.

The agreement is triggered only upon a certain threshold of states enacting electoral reallocation legislation. The state legislatures together would then establish a direct vote and effectively circumvent the Electoral College system if enough electoral votes switch. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) recommends that the present manner of allocating electors shall remain in force until enough states have signed on as to account for a majority of electoral votes. In 2020, the plan had been adopted by fifteen states and the District of Columbia. These states have 196 electoral votes, which is 36 percent of the Electoral College and 73 percent of the 270 votes needed to give the compact legal force.

Congressional District method

Other observers argue that the current electoral rules of Maine and Nebraska should be extended nationwide. As previously noted, the winner in each of those two states is only guaranteed two of Maine's four and two of Nebraska's five electoral votes, with the winner of each Congressional district in those states receiving one electoral vote. Using the California example again, Gore won 33 of the state's Congressional districts and the state overall, while Bush won 19 Congressional districts. With the two votes for the state's overall result added, the state's electoral votes would then have gone 35â19 for Gore.

However, this kind of allocation would still make it possible for the loser of the popular vote to become president. Dividing electoral votes by House district winners would create yet another incentive for partisan gerrymandering. Direct election proponents oppose the district method also because candidates would focus on the votes of only the competitive districts, making the votes of even fewer Americans matter than when candidates focus on votes in competitive states.[24]

Another perceived problem with this suggestion is that it would actually further increase the advantage of small states. In winner-take-all, the small states' disproportionately high number of electors is partially offset by the fact that large states with their big electoral blocks are such a highly desirable boon to a candidate that large swing states actually receive much more attention during the campaign than smaller states. In the proportional vote or District Method, this advantage of the large states would be gone.

Yet another argument with both the Congressional District Method and the Proportional vote is that even if it is considered superior as a nationwide system, winner-takes-all generally maximizes the power of an individual state and thus while it might be in the interest of the nation, it is not in the interest of the state to adopt any other system. Since the United States Constitution gives the states the power to choose their method of appointing the electors, nationwide Congressional District Method without a constitutional amendment mandating it seems unlikely, and the passage of such an amendment seems equally unlikely since the House delegations of the largest states (against whose interests such a system would be), taken together, easily surpass the one third of the House size that is needed to block a constitutional amendment.

Abolishing the non-proportional electors (drop 2)

Another proposed reform is to make the number of electors that each state has the same as its number of Representatives (effectively the same as the current system, except taking two electoral votes from each state). This plan, sometimes called "drop 2," could still be seen as inherently unfair, as some of the least populous states would be proportionally overrepresented while some of the slightly more populous single-representative states would be significantly underrepresented (for example, Wyoming, the least populous state, has one Representative for 510,000 inhabitants; Montana has one Representative for 935,000 inhabitants; compare this to California, which averages one Representative for each 681,000 Californians).

Proponents of this suggestion say that this will preserve the Electoral College's benefits and make the system more democratic at the same time. Others say this will remove the extra power given to the small states intended to make elections more fair and there would still exist the phenomenon of non-swing states being ignored.

The late historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. had proposed decreasing the number of electors in the Electoral College from 538 to 436, with each state allotted the same number of votes as their number of representatives in the House of Representatives (with one vote for the District of Columbia). Each state would be required to use a winner-take-all system. Then, 102 votes would automatically be given to the winner of the national popular vote. Schlesinger felt that this would maintain the stability of a two-party system (as a winner-take-all system already does), while virtually guaranteeing that the person who wins the national popular vote would automatically win the Presidential election.

The District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act

Legislation currently before the Congress (H.R. 1905 and S. 1257) regarding the District of Columbia vote in the United States House of Representatives would permanently increase the size of the House to 437 members. One of the two new seats would go to the federal capital (Washington, D.C.); the other would go to the State of Utah per the 2000 U.S. Census apportionment.

The additional seat to Utah would increase its House delegation to four, consequently increasing its number of Electoral College votes to six. As Washington, D.C. is already given three Electoral College votes by the Twenty-third Amendment, receiving a House seat would neither increase nor decrease its share of the Electoral College.

If the proposed legislation becomes law and survives any challenges to its constitutionalityâWashington, D.C. is not a state and thus is not allowed representation in Congress under Article I, Sections 1 and 2 of the U.S. Constitution, nor under Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendmentâthe total number of Electoral College votes would increase by one to 539. The majority needed to elect a President would remain 270 electoral votes.

On April 19, 2007 the House of Representatives passed H.R. 1905 by a vote of 241 in favor, 177 against, 1 present (abstained).[25] On September 18, 2007 the Senate fell three votes short of passing a motion to invoke Cloture regarding S. 1257 (60 votes in favor in order to invoke Cloture).[26]

The Bayh-Celler Amendment

The closest the nation has ever come to abolishing the Electoral College occurred during the 91st Congress.[27] The Presidential election of 1968 had ended with Richard Nixon receiving 301 electoral votes to Hubert Humphrey's 191. Yet, Nixon had only received 511,944 more popular votes than Humphrey, equating to less than 1 percent of the national total.

Representative Emanuel Celler, Chairman of the US House of Representative's Judiciary Committee responded to public concerns over the disparity between the popular vote and electoral vote by introducing House Joint Resolution 681, an Amendment to the United States Constitution which would have abolished the Electoral College and replaced it with a system wherein the pair of candidates who won at least 40 percent of the national popular vote would win the Presidency and Vice Presidency respectively. If no pair received 40 percent of the popular vote, a runoff election would be held in which the choice of President and Vice President would be made from the two pairs of persons who had received the highest number of votes in the first election. The word "pair" was defined as "two persons who shall have consented to the joining of their names as candidates for the offices of President and Vice President."[28]

On April 29, 1969, the House Judiciary Committee voted favorably, 28-6, to approve the Amendment.[29] Debate on the proposed Amendment before the full House of Representatives ended on September 11, 1969,[30] and was eventually passed with bipartisan support on September 18, 1969, being approved by a vote of 339 to 70.[31]

On September 30, 1969, President Richard Nixon gave his endorsement for adoption of the proposal, encouraging the Senate to pass its version of the Amendment which had been sponsored as Senate Joint Resolution 1, by Senator Birch Bayh.[32]

On October 8, 1969, The New York Times reported that the legislatures of 30 states were "either certain or likely to approve a constitutional amendment embodying the direct election plan if it passes its final Congressional test in the Senate." Ratification of 38 state legislatures would have been needed for passage. The paper also reported that 6 other states had yet to state a preference, 6 were leaning toward opposition and 8 were solidly opposed.[33]

On August 14, 1970, the Senate Judiciary Committee sent its report advocating passage of the Amendment to the full Senate. The Judiciary Committee had approved the proposal by a vote of 11 to 6. The six members who opposed the plan, Democratic Senators James Eastland of Mississippi, John Little McClellan of Arkansas and Sam Ervin of North Carolina along with Republican Senators Roman Hruska of Nebraska, Hiram Fong of Hawaii and Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, all argued that although the present system had potential loopholes, it had worked well throughout the years. Senator Bayh would indicate that supporters of the measure were about a dozen votes shy from the 67 needed for the Amendment to pass the full Senate. He called upon President Nixon to attempt to persuade undecided Republican Senators to support the plan.[34] However, Nixon, while not reneging on his previous endorsement, chose not to make any further personal appeals to back the legislation.[35]

Open debate on the Amendment finally reached the Senate floor on Tuesday, September 8, 1970,[36] but was quickly faced with a filibuster. The lead objectors to the Amendment were mostly Southern Senators and Conservatives from small states, both Democrats and Republicans, who argued abolishing the Electoral College would reduce their states' political influence.[35]

On September 17, 1970, a motion for cloture, which would have ended the filibuster, failed to receive the 60 votes, or two-thirds of those Senators voting, necessary to pass. The vote was 54 to 36 in favor of the motion.[35] A second motion for cloture was held on September 29, 1970, this time failing 53 to 34, or five votes short of the required two-thirds. Thereafter, the Senate Majority Leader, Mike Mansfield of Montana, moved to lay the Amendment aside so that the Senate could attend to other business.[37] However, the Amendment was never considered again and died when the 91st Congress officially ended on January 3, 1971.

Since January 3, 2019, joint resolutions have been made proposing constitutional amendments that would replace the Electoral College with the popular election of the president and vice president. Unlike the BayhâCeller amendment, with its 40 percent threshold for election, these proposals do not require a candidate to achieve a certain percentage of votes to be elected.

Notes

- â This number is reached by adding the 435 Representatives, 100 Senators, and 3 electoral votes for the District of Columbia

- â Madison Debates, May 29, 1787 Avalon Project. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Madison Debates, June 2, 1787 Avalon Project. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Madison Debates, September 4, 1787 Avalon Project. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Madison Debates, September 6, 1787 Avalon Project. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Federalist No. 39 Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 and the Election of 1840 Statutes and Stories, August 3, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Prior to the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment, this only meant the House of Representatives.

- â The number of electors allocated to each state is based on Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution.

- â Sabrina Eaton, Brown learns he can't serve as Kerry elector, steps down Cleveland Plain Dealer October 29, 2004. (reprint at Edison Research). Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Michigan Election Law Section 168.47 Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â "The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted."

- â 3 U.S. Code § 15 - Counting electoral votes in Congress Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â Bush v. Gore, December 12, 2000. (Justice Stevens dissenting) (quote in second paragraph) Retrieved November 23, 2020.

- â 16.0 16.1 William C. Kimberling, The Electoral College (FEC Office of Election Administration, 1992, ISBN 978-1508718017).

- â Richard B. Darlington, The Electoral College: Bulwark Against Fraud Cornell University. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â Ron Paul, Hands Off the Electoral College lewrockwell.com, December 28, 2004. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â Mark Livingston, Banzhaf Power Index University of North Carolina, Department of Computer Science. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â Andrew Gelman and Jonathan Katz, The Mathematics and Statistics of Voting Power Statistical Science 17(4) (2002):420-435. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â Jerry Fresia, Third Parties? ZNet, February 28, 2006. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â James A. Michner, Presidential Lottery: The Reckless Gamble in Our Electoral System (Dial Press Trade Paperback, 2016, ISBN 978-0812986822).

- â Philip R. Schmidt, The Electoral College and Conflict in American History and Politics Sociological Practice: A Journal of Clinical and Applied Sociology 4(3) (September, 2002): 195-208.

- â Monideepa Talukdar, Robert Richie, and Ryan O'Donnell, Fuzzy Math: Wrong Way Reforms for Allocating Electoral College Votes Fair Vote, September 16, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- â Breakdown of House vote on H.R. 1905 Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- â Breakdown of Senate vote on Cloture motion Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- â For a more detailed account of this proposal see Lawrence D. Longley and Alan G. Braun, The Politics of Electoral College Reform (Yale University Press, 1972, ISBN 978-0300015881).

- â "Text of Proposed Amendment on Voting," The New York Times, April 30, 1969, 21.

- â "House Unit Votes To Drop Electors" The New York Times, April 30, 1969, 1.

- â "Direct Election of President Is Gaining in the House," The New York Times, September 12, 1969, 12.

- â "House Approves Direct Election of The President," The New York Times, September 19, 1969, 1.

- â "Nixon Comes Out For Direct Vote On Presidency," The New York Times, October 1, 1969, 1.

- â "A Survey Finds 30 Legislatures Favor Direct Vote For President," The New York Times, October 8, 1969, 1.

- â "Bayh Calls for Nixon's Support As Senate Gets Electoral Plan," The New York Times, August 15, 1970, 11.

- â 35.0 35.1 35.2 "Senate Refuses To Halt Debate On Direct Voting," The New York Times, September 18, 1970, 1.

- â "Senate Debating Direct Election," The New York Times, September 9, 1970, 10

- â "Senate Puts Off Direct Vote Plan," The New York Times, September 30, 1970, 1.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burin, Eric (ed.). Picking the President: Understanding the Electoral College. Digital Press at The University of North Dakota, 2017. ISBN 978-0692833445

- Foley, Edward B. Presidential Elections and Majority Rule: The Rise, Demise, and Potential Restoration of the Jeffersonian Electoral College. Oxford University Press, 2020. ISBN 978-0190060152

- Keyssar, Alexander. Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? Harvard University Press, 2020. ISBN 978-0674660151

- Kimberling, William C. The Electoral College. FEC Office of Election Administration, 1992. ISBN 978-1508718017

- Longley, Lawrence D., and Alan G. Braun. The Politics of Electoral College Reform. Yale University Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0300015881

- Michner, James A. Presidential Lottery: The Reckless Gamble in Our Electoral System. Dial Press Trade Paperback, 2016. ISBN 978-0812986822

- Ross, Tara. Enlightened Democracy: The Case for the Electoral College. Colonial Press L.P., 2012. ISBN 978-0977072224

- Ross, Tara. Why We Need the Electoral College. Gateway Editions, 2019. ISBN 978-1684510139

- Wegman, Jesse. Let the People Pick the President: The Case for Abolishing the Electoral College. St. Martin's Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1250221971

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- U.S. Electoral College FAQ (www.archives.gov)

- Historical Documents on the Electoral College

- 270towin.com

- The Green Papers Commentary Proposals and Prospects for Electoral College Reform, January 23, 2001

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.